‘Not interesting from the point of view of history’: renovated public spaces in Moscow and cultural clashes

Moscow is currently undergoing a phase in which urban public spaces are being rapidly developed, with new ones being created and existing ones transformed. This development reflects the many ways in which the structure of the post-Soviet metropolis is changing, as compared to the Soviet city of Moscow. New constellations of business life, new policies and new aesthetics are emerging in the urban environment, as are new publics. Predictably, this transformation is accompanied by a multitude of cultural conflicts, whose severity varies over a wide range. They include experts criticizing the standards and practices of construction or restoration of buildings, direct clashes between residents and city officials, as well as conflicts between developers and the defenders of the city's historic heritage. Over the past 20 years almost every aspect of urban public space existing in the Russian capital has been affected by such conflict.Footnote 1

The diversity of urban publicsFootnote 2 has also increased in the rapidly developing metropolis. Each public began to lay claim to visibility in the urban space, to invent different ways of using it and new rules of communication in a densely populated and variegated urban environment. Economic growth has generated multiple spaces of consumption that are often combined with leisure spaces, a phenomenon known to be typical of large cities since the second half of the nineteenth century when department stores and arcades came into being. Today, people come to Moscow's shopping malls with families to spend the whole day there shopping, eating out and relaxing. For the post-Soviet city, the functioning of these spaces and the behaviour of urban residents in them is a new phenomenon, as the way in which consumption is combined with spare-time activities there today was not typical of the public culture of cities of the Soviet period. In them, the most important role was played by ‘parks of culture and leisure’ and exhibitions, and primarily in Moscow by the All-Russia Exhibition Centre and Gorky Central Park of Culture and Leisure. New public spaces brought about a new aesthetic. The image of contemporary Moscow produced both by the city authorities and the mass media is that of a bustling, vibrant, colourful and at the same time well-organized, clean and safe ciy – rebuilt and renewed in every sense of the word. This image involved new textures of urban fabric, new colours, new lighting solutions, new requirements as to the newness and cleanness of surfaces and so on.

Such transformation of the urban environment could not but lead to serious problems concerning the status and the preservation of historical heritage in the Russian capital and to noticeable changes in the urban historical culture Footnote 3 in general. Moscow's recent history has seen numerous cases of experts and civic groups struggling for the preservation of ‘authentic’ historical and architectural heritage in the classical sense. Meanwhile, the scale and complex nature of transformations affecting a number of historic sites and the fact that these transformations are undeniably in keeping with the overall development trends of urban public spaces in the world make it necessary to look at Moscow in the context of a changing urban historical culture. At the same time, we need to ask what is idiosyncratically Muscovite and Russian in this new historical urban culture, how it is connected to the emergence of new urban publics in the city and what is reflecting more general, even global processes.

To study these two interrelated processes, i.e. the transformation of historical culture in the post-Soviet metropolis during the last two decades and the emergence of a new culture of public communication in the city, we chose the particularly instructive case of the State Historical, Architectural, Art and Landscape Museum-Reserve Tsaritsyno.Footnote 4 This case represents closely intertwined features of Russian urban history over the last two centuries and the more recent history of Moscow.Footnote 5 Tsaritsyno was one of the first historical spaces in post-Soviet Moscow to undergo an all-round reconstruction. In this respect, it was second to Manezhnaya Square where in the late 1990s – early 2000s the ‘Okhotny Ryad’ underground shopping mall was built, and the square itself was turned into a recreation area. Tsaritsyno was reconstructed between 2005 and 2007 under the auspices of Mayor Yuri Luzhkov who served from 1992 to 2010. This project was timed to celebrate the 860th anniversary of Moscow and intended to represent the ideological and financial viability of city authorities, who proclaimed themselves the heirs to the ‘Golden Age of Catherine the Great’, ‘whipping into shape’ the palaces and the park in order to give them to the people as a ‘present’.

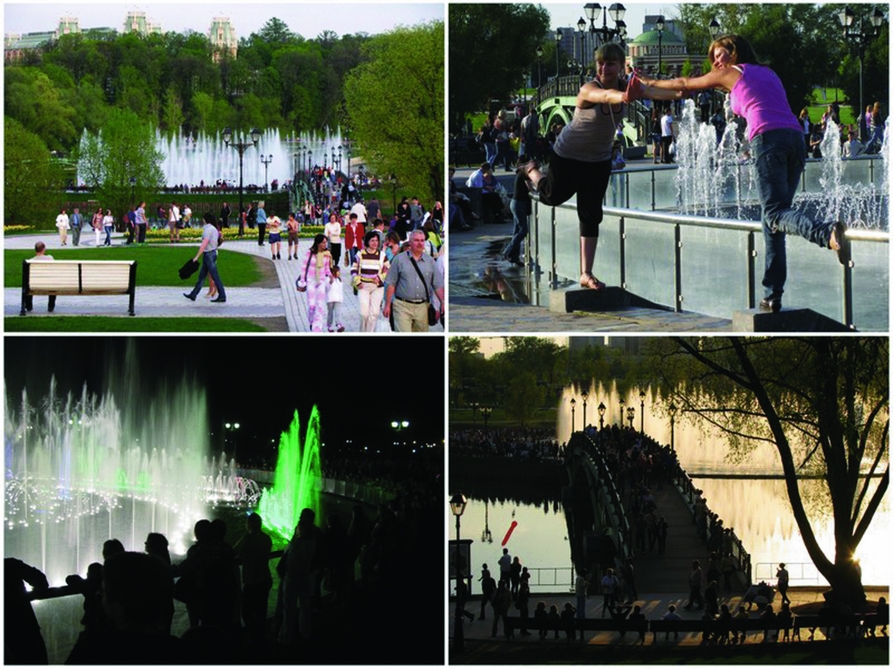

For anyone visiting Tsaritsyno for the first time now, in 2015–16, it would be hard to recognize what happened here several years ago and to imagine the extent of the cultural conflict that arose as the reconstruction was in progress, and then after the completed project was presented to experts and the general public. Today's Tsaritsyno (see Figure 1) is a large park area with the museum part on the outskirts of the city. It enjoys immense popularity with residents of nearby neighbourhoods and Muscovites from all over the city as well as those from the suburbs, tourists from all regions of the former Soviet Union and, increasingly, from abroad.Footnote 6 According to the number of positive reviews and recommendations, Tsaritsyno is the fifth most popular sight to visit in Moscow on the TripAdvisor website, next only to the several points of interest at Red Square and the Tretyakov Gallery.

Figure 1: Tsaritsyno's architecture today: different buildings by Vasily Bazhenov and The Grand Palace.

In recommending this place to others as a public recreation area, Russian contributors to TripAdvisorFootnote 7 visibly make a point of underlining and appreciating the modernization of Tsaritsyno as an important breakthrough which required great efforts and led to great results. In their positive accounts, visitors to Tsaritsyno tend to inscribe it in a number of social, historical and stylistic contexts that can be labelled ‘civilization’, ‘order’ and ‘achievement’. The key context is a comparison with European parks and palaces: ‘This is Moscow's Versailles, Schönbrunn, etc.’ (a Russian male visitor); ‘The surviving buildings and the palace itself impressed [me] by their grandeur and beauty. It was like we were not in Moscow but somewhere in Prague or its surroundings’ (a Russian female visitor). The comparison with St Petersburg and Peterhof is drawn frequently by Russian as well as foreign visitors: ‘Great example of garden arts in Moscow. I'd say that it is an Spb's (St Petersburg – BS, NS) place rather than the Moscow's one’ (a Russian female visitor writing in English); ‘We knew there were not many places in Moscow where you could see some Romanov's houses or palaces, like in Saint Petersburg. It was interesting to discover such place in Moscow. Do not miss visiting museum inside, wonderful and royal style interiors’ (an American female visitor). Being proud of a renovated place in their city, contributors show a desire to present it to foreigners: ‘The place in Moscow which one can rightly be proud of and which one should show to all one's Russian and foreign friends!’ (a Russian female visitor); ‘A wonderful place for strollers and history-lovers. The ensemble that was created on the orders of Catherine, remained unfinished and in ruins for hundreds of years, finally pleases Muscovites with its beauty. Not only the palace and other buildings are beautiful, the cleaned ponds and the alleys of the park are also beautiful. Singing fountains in the evening are bonus for visitors’ (a Russian female visitor). For many of the visitors who have witnessed the complete transformation of Tsaritsyno and approved of it, Tsaritsyno functions as a kind of exhibition of recent achievements of Moscow's economy: ‘My first-time visit in Tsaritsyno was in 2001. It was, pardon my French, a huge public toilet with crap alongside of the pond shore and reeking barbecue fires all over the place. . .He [i.e. Luzhkov] created a real European architectural ensemble which one can show to foreign guests without being ashamed. It recreates the atmosphere of Russian expanse with a hint of Western architecture from the time when “European” culture began penetrating here. . .Very warm atmosphere for a weekend with your family. Recommended!!!’ (a Russian male visitor); ‘Liked it very much! Historic buildings recreated. I know Luzhkov is being railed against by many, but I am no art-historian, and to my taste everything has been restored well’ (a Russian male visitor).

It has been almost 10 years since the renewed Tsaritsyno began functioning as (1) a high-quality recreational area, something which this part of Moscow had totally lacked before; (2) a modern public space open for different uses and (3) as a progressive, by Moscow standards, museum carefully working on relations with various publics (see Figure 2). Over this decade, the adverse reactions and the memories of confrontation that took place here were smoothed out. Still, negative feedback keeps coming, reminding readers of the changed historical status of the place and of other possible views on its usage. ‘Luzhkov-style replica instead of the beautiful picturesque ruins that stood there for 200 years. So sorry for the beautiful monument this place had been before Luzhkov's intervention’ (a Russian male visitor); ‘Beautiful and pompous but not impressive. A remake is a remake. . .One can have a good time here just like in any well-designed park. . .no historical atmosphere is perceptible after the reconstruction’ (a Russian female visitor). ‘There is no feeling of the past’, ‘there is no feeling of authenticity’ – such reviews, though fewer in number, are visibly present on the website. What they reflect is the conflict that we focus on in this article.

Figure 2: Tsaritsyno as a recreational space and a space for the development of Moscow public culture.

‘Not interesting from the point of view of history’: this verdict by a Russian female visitor can serve as a starting point. Tsaritsyno is extremely interesting from the point of view of history, if we understand history as a theoretically saturated history of modern urban spaces and, specifically, of urban and suburban public spaces in Moscow. But in order to show this we need to go back to Tsaritsyno's origin in the eighteenth century and schematically trace the main phases of its evolution.

Tsaritsyno: an incomplete project (1775–2005)

The reign of Catherine II (1762–96) is often called the ‘Golden Age’ of the Russian Empire and was also an important time in the history of Russian urban culture. Continuing what Peter I had started, the empress ordered master plans to be drawn up for cities. She regulated her subjects’ daily life in accordance with the new standards of the civilizing process (to quote Norbert Elias)Footnote 8 and reformed Russia's administrative system. This shaped Russian urban life for decades to come, in certain aspects, even up to the 1917 revolution.Footnote 9

During this period, the country estates of the nobility developed a specific culture that was to constitute a major element of the Catherinian heritage. Until the second half of the seventeenth century, the boyars and nobles used their country estates exclusively for economic purposes.Footnote 10 In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, members of the tsar's family and courtiers began to build pompous country palaces. This was a process that gained particular momentum following the ‘Manifesto Granting Liberties and Freedoms to the Russian Nobility’ issued by Catherine II's spouse and predecessor Peter III in 1762 and ‘The Charter of the Rights, Liberties and Privileges of the Russian Nobility’ issued later by Catherine herself. This legislation exempted the nobility from obligatory state and military service and granted them some economic and political privileges, thus encouraging them to take more care of their estates. The result of these social changes was the formation of the classical Russian estate as a harmoniously arranged space that combines nature and culture and serves as a space of both privacy and of amusements.Footnote 11

Estate life became a key component of the Catherinian ‘Golden Age’. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the country ‘nests of the gentry’ gave rise to what came to be known as the ‘country estate myth’, i.e. nostalgic feelings reflecting a longing for a harmonious and well-maintained life.Footnote 12 Additionally, contemporary scholars emphasize the contribution of estates to the development of urban architecture. For example, Еvgenia Kirichenko points out that while the urban environment was shaped in accordance with the ideals of classical regularity, estates were places of architectural experiment which were later expanded in the urban space: ‘What was unacceptable in a city became normal and was considered not merely possible but mandatory and natural in an estate.’Footnote 13 The nineteenth century was also the time when dachas, the weekend and summer houses of city dwellers, began to emerge around the nobles’ estates and a new suburban culture developed.

Founding an imperial residence in Tsaritsyno was an important part of Catherine II's efforts to transform Moscow. The empress contributed greatly to the formation of an estate culture in and around Moscow by frequently visiting noblemen's estates in the area and by commissioning projects for her own residences, chief of which was Tsaritsyno.Footnote 14 This property was located 13 kilometres from the Kremlin on the banks of large ponds, and was previously called Chernaya Gryaz’ (‘black mud’). Initially, it belonged to Sergey Cantemir, the son of the famous Count Dimitrie Cantemir, a companion of Peter the Great. Catherine saw and liked it during one of her trips around Moscow. In 1775, the estate was purchased from Cantemir and renamed Tsaritsyno Selo (‘Tsarina's village’). It was supposed to become a counterpart to Tsarskoye Selo (‘Tsar's village’), the imperial residence near St Petersburg.Footnote 15 Old buildings were demolished to make space for a new ensemble designed by the chief court architect Vasily Bazhenov and approved by the empress. Apart from four palaces, the most important of which were those of Catherine and her son the future Emperor Paul I, it included a large kitchen building and several buildings for the court as well as small houses for servants.

The architectural style chosen by Bazhenov reflected the new ‘Gothic’ fashion of the time which involved both fantastic reminiscences of medieval European architecture as well as a dialogue with the national architectural tradition. Initially, as many researchers note, Bazhenov's replication of ancient Russian architectural forms and those of the Moscow Kremlin was a game,Footnote 16 but later on it became a style of its own.

The area surrounding the palace ensemble was to become a ‘regular garden’, stripped of its household functions and turned into a park designed exclusively for walks and amusements.Footnote 17 The English gardener Francis Reid was employed to create a park in Tsaritsyno.Footnote 18 Although Bazhenov and Reid did not work well together, the space they created was integrated both in terms of function and of style. The ‘English garden’ design follows the natural landscape of Tsaritsyno offering a suitable frame for Bazhenov's fantasy architecture. For example, the direct arrow of the ‘Gothic’ lime avenue turns into a number of small curved paths, and there are several levels at which one can walk in the park, each level with its own features and surprises, suggesting different views.

But the construction of the suburban royal residence was not to be completed. It shared the fate of another of Bazhenov's projects initiated by Catherine the Great, which involved a reconstruction of the Kremlin and the construction of a new Kremlin Palace.Footnote 19 After 10 years of construction works, in June 1785, the empress visited Tsaritsyno and was dissatisfied by the almost finished palaces which she believed would be uncomfortable to live in. Soon she suspended Bazhenov and commissioned another architect, Matvey Kazakov, to complete the construction. He intended to build a single new Grand Palace instead of Bazhenov's two central palaces, which were dismantled, while other buildings, such as the so-called ‘Khlebniy dom’ (Kitchen House), the Medium and the Small Palace, the Knights' Houses, the quaint Large Bridge, Ornamental Bridge and the Ornamental Gate remained intact. Kazakov's new design for the main palace was intended to be more in line with what a royal ceremonial residence was believed to look like at the end of the eighteenth century. However, this project was not implemented either: following Catherine's death in 1796, Paul I ordered the construction works in Tsaritsyno to cease. The all-but-complete ensemble remained unfinished and soon began to decay and collapse. The Grand Palace was a ruin until Luzhkov's reconstruction in 2005–07 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: The Grand Palace on a postcard, the beginning of the twentieth century.

Still, after becoming a public park under Alexander I in the early nineteenth century, the incomplete estate experienced a sudden heyday as a popular suburban venue. This was due to the efforts of the head of the Kremlin Construction Office Peter Valuev, who used Tsaritsyno as his summer estate, and the park became Muscovites’ favourite place for country walks. Valuev issued orders to clean up the park and the ponds, to restore the approach roads and to build fences and guard huts so as to ensure security. In the park, arbours and alcoves, pavilions, piers, a coffee-house and a hotel were built, and a variety of entertainment facilities (swimming, boating, etc.) were made accessible to the public. Despite these erratic mundane activities, the Tsaritsyno's neo-Gothic park ensemble successfully fitted into the concept of the romantic estate and gained popularity in the early nineteenth century, in which period it was the landscaped park that constituted the ‘proper’ estate ensemble.Footnote 20 The beauty of the landscape and the mysterious story of the ruin that was seen as a symbol of the majesty and ruthlessness of history were the subject of numerous travelogues responsible for the romantic aura that has surrounded Tsaritsyno in the centuries to come.Footnote 21

Another period of decline followed after Valuev's death in 1814. It was by good fortune that the buildings avoided being scrapped or becoming an almshouse for peasants (such plans existed).Footnote 22 But without constant care, they gradually fell into disrepair. In the mid-nineteenth century, Tsaritsyno, like many other abandoned imperial and aristocratic estates in Russia, became the target of private enterprise development, with dachas being built on their outskirts.Footnote 23 In the case of Tsaritsyno, this process was accelerated by the construction of a railroad nearby in 1866. Gradually, the typical features of a popular summer resort appeared, such as amusement facilities, summer theatres, etc. Along with the other Moscow residence of Catherine the Great, Petrovsky Park, Tsaritsyno once again became a part of Moscow's entertainment landscape. In the early twentieth century, the ‘Society for the Improvement of the Tsaritsyno Area’ was founded and contributed significantly to the introduction of state-of-the-art urban amenities such as street lighting, athletic grounds and public telephones to the dacha settlements.Footnote 24

After the 1917 revolution, Tsaritsyno was renamed Lenino, and after being united with the nearby settlements it became the biggest urban-type settlement in the Moscow area.Footnote 25 Parts of the palace ensemble built by Bazhenov were spontaneously put to use as housing and office buildings (for example, there were communal apartments in the Kitchen House between the 1920s and 1970s), while the park still enjoyed popularity as a place for picnics, outings and dacha activities.

In the discussions about the Moscow reconstruction plan in the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Tsaritsyno Park was already conceived of as a high-potential recreational space.Footnote 26 Proposals were put forward in the 1930s to use the estate and the ruins of the palace as a health resort or as a sparkling wine factory, but just like the pre-revolutionary projects they were never implemented. It was not until 1984 that, finally, a museum was founded in Tsaritsyno. However, contrary to what one would assume, it was neither a museum of eighteenth-century architecture nor of the culture of the ‘Golden Age of Catherine the Great’ but a museum of arts and crafts of the peoples of the USSR.

The history of the museumification of Tsaritsyno reflects the difficult process of turning the estate into a heritage site. The difficulty had in part to do with the atypical semi-ruined state of the unfinished imperial residence and partly with the fact that the neo-Gothic style of Bazhenov's buildings did not fit the image of a classic Russian estate that was shaped by the descriptions in local historians’ books. Unlike other residences of the tsar's family and other noblemen near St Petersburg and Moscow (Peterhof, Tsarskoe Selo, Pavlovsk, Oranienbaum, Kuskovo, Kolomenskoye, Ostafyevo) which were granted museum or heritage site status in the first half of the twentieth century, Tsaritsyno remained a derelict museum.Footnote 27 In 1927, a local folklore and history museum was founded that was housed in one of the Bazhenov buildings, but it was closed in 1937, following the crackdown on the local history movement in the USSR.Footnote 28 Even though Bazhenov and Kazakov were recognized in the mid-twentieth century as the fathers of the Russian national architectural tradition, in the Soviet era Tsaritsyno never became a museum of eighteenth-century culture. It was not until the 1990s that it acquired a legal status that did justice to the architectural value of its buildings.

After Tsaritsyno – then called Lenino – became part of Moscow in 1960, the development of adjacent areas intensified, prompting restorers and defenders of local historical heritage to step up their efforts aimed at conservation of the ensemble and recognition of it as a heritage site. The result was the Tsaritsyno Arts and Crafts Museum being granted the status of museum-reserve in 1993. The ensemble and the surrounding area, which used to be just a space for a thematically unrelated exhibitions of arts and crafts, became a heritage site in its own right. While the restoration of small Bazhenov buildings began in the 1980s, the Grand Palace remained a ruin and the Kitchen House was in a deplorable state. During the 1980s and 1990s, the park was neither museumified nor cultivated and became an arena for chaotic activities. Some dachas and privately owned houses remained there, as did various institutions that had moved in during the Soviet era. The park attracted various subcultures from hippies to neopagans and Tolkien fans with wooden swords. Athletic communities such as volleyball players and also chess players reclaimed parts of the park, as did rock climbers who used its ruins as climbing walls, as well as drunkards who benefited from the park's desolation. In general, prior to the ‘Luzhkov restoration’ Tsaritsyno was reputed to be a half-abandoned, unsafe, but ‘romantic’ place. Locals used parts of it as a recreational area, but only during daytime.

Summing up, our brief excursion into the history of Tsaritsyno before the 2000s reveals a number of major trends in its evolution. First, the history of this heterogeneous space with undefined functions and constantly changing status is inextricably linked with the development of the city of Moscow and with the interests and abilities of diverse urban publics. Second, attempts to use Tsaritsyno as a public space have a wave-like nature. The park oscillates between inclusion in the overall urban system of activities and falling out of it, deteriorating into disrepair and becoming a place of a very limited use. Third, historically, the image of Tsaritsyno as ‘a romantic place’ gradually and almost completely superseded its previous image as an entertainment space, which it had originally been intended to be as Catherine the Great dreamed of watching fireworks over the Tsaritsyno ponds, and which it occasionally became when some efforts were made to cultivate it (at the beginning of the nineteenth century, for example). Fourth and last, the reconstruction began when Tsaritsyno already (even if only recently) had heritage site status which in city dwellers’ eyes was associated with historical and architectural value, even though the state of the park and some of the buildings in it indicated that this valuable place was in need of serious restoration. The renovation of Tsaritsyno at the beginning of the new century, however, drastically changed many of the characteristics of this place and the way it was perceived as a historical and cultural space.

Heirs of the ‘Golden Age’: ‘fantasy restoration’, its ideology and results

In the early 2000s, the question arose as to exactly what place the museum-reserve Tsaritsyno was to occupy in the changing urban culture of Moscow. This issue was addressed both by the city authorities who spared no expense on ambitious projects, commercial as well as symbolic, and by the management of the museum-reserve who wanted to increase its importance as an architectural heritage site and rallied the support of museum workers to this end. Victor Egorychev, who became director of the museum-reserve in 2000, promoted the idea of actualizing the historical potential of the imperial residence. He stressed the need for restoration and good branding in order for the place to be competitive. The Tsaritsyno renewal and branding project he initiated was called ‘Catherine the Great's Tsaritsyno – the Moscow Coliseum.’Footnote 29 Unlike many other unrealized restoration projects that involved the rebuilding of the Grand Palace in one way or another, this one envisaged conservation and museumification of the ruin. The idea of the ‘Moscow Coliseum’, perhaps somewhat utopian, was to preserve the architectural value of the entire ensemble in an unchanged form while creating a modern hi-tech exhibition space inside the ruins and using cutting-edge audio-visual know-how such as light chaser shows for infotainment theme events dedicated to the Catherinian ‘Golden Age’.

Another project to revive the estate was put forth in the late 1990s by a research team of the the Scientific-Research and Design Institute of the General Plan of the City of Moscow headed by Irina Bakhtina. Under this project, published in 2004, all the buildings in Tsaritsyno, the extant as well as the extinguished ones, were to be rebuilt and a tourist facility area was to surround the protected zone.Footnote 30

However, the museum-reserve which at that time was a federal institution did not have enough money to solve its current household problems, much less ambitious restoration projects. The museum management's plan was to make Tsaritsyno a municipal institution because the Moscow authorities were far wealthier and could perhaps be persuaded of the feasibility of the ‘Moscow Coliseum’ project. The transition ultimately secured the place and the role of the Tsaritsyno Park and museum in Moscow's cultural universe but, at the same time, it also ushered in the ‘Luzhkov restoration’, which turned out to be more of a rebuilding. As early as 7 September 2005, the Public Council of the Moscow mayor approved a project for the rebuilding of the Grand Palace and the Kitchen House and a comprehensive reconstruction of the park. Neither the historical meanings associated with the ruins and with the ‘romantic abandonment’ of the place, nor the cultural meanings that could have been conveyed by a conserved ruin, fitted into the municipal authorities’ culture and history policy.

Their ambitious plans were aimed, on the one hand, at symbolic assertion of continuity between the powers that be and Russia's past and, on the other hand, at large-scale restructuring and transformation of urban spaces. Because the changing city's need for comfortable recreational spaces was at that point obvious, the neglected and unsafe Tsaritsyno Park was transformed into a public leisure area with night lighting, security service, flower beds, toilets, segways, a boat-rental point and an adventure park. A series of similar projects followed later, including the refurbishment of Gorky Central Park of Culture and Leisure, the protracted upgrade of the All-Russia Exhibition Centre, the construction of a full-scale mock-up of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich's wooden palace entertaining the visitors of Kolomenskoye landscaped park, and a number of smaller projects. The symbolic meaning of these initiatives manifested itself most prominently in the reasoning used in the authorities’ public statements and press comments at the time.

First, the revived Tsaritsyno represented an argument in the symbolic competition between Russia's two capitals, as it was meant to compensate for the absence of imperial residences around Moscow (indeed, in contrast to St Petersburg, which is surrounded by a chain of imperial estates, Tsaritsyno is virtually the only estate in Moscow that was at least designed as a suburban imperial residence).Footnote 31 The complete reconstruction of the Grand Palace in Tsaritsyno, which was supposed to become a venue for representative events as well as for exhibitions, was perceived as a response to the reconstruction of the Constantine Palace and park in Strelna near St Petersburg undertaken under the auspices of President Vladimir Putin.Footnote 32

Second, this large-scale construction project allowed the Moscow authorities to act as the heirs of the ‘Golden Age of Catherine the Great’. The Soviet word dolgostroy, meaning a long-delayed construction project, became a popular and symbolic label for the history of Tsaritsyno, with the first deputy mayor and head of Architecture and Construction Department of the Moscow city government, Vladimir Resin, saying that Tsaritsyno, Russia's ‘longest-standing dolgostroy’ that had remained unfinished for more than 200 years, would now finally be completed.Footnote 33

In the ideological justification of the reconstruction, it was not historical authenticity that was applied as the chief criterion for the value of Tsaritsyno, but its symbolic significance and prospective functionality. It was designed to meet the entertainment needs of the broad new public, and to provide representational functions for the palace buildings and recreational functions for the park.Footnote 34 These criteria shaped all architectural, stylistic and historical decisions implemented during the reconstruction. The concept of historical culture that the renewed Tsaritsyno was designed to represent and to promote was a profoundly different one, if we compare it to the traditional historical concept of authenticity of cultural heritage. Architects and historians described the restoration plan for the Grand Palace as ‘fantasy restoration’. It was harshly criticized, particularly by the director of the State Institute of Art Studies, Professor Alexei Komech, who published an article in newspaper Izvestia titled ‘We will have the past we want and the historical heritage we will make’.Footnote 35 But neither the numerous critical responses of experts nor the discussion in the media affected the way in which this reconstruction was done.Footnote 36

The ‘fantasy restoration’ resulted in the Grand Palace and the Kitchen House being ‘completed’ using modern materials and turned into multifunctional exhibition and concert rooms. The atrium of the Kitchen House was furnished with an organ and covered with a transparent roof. The interiors of the Grand Palace's main halls had never existed, as the Palace had never been finished, but now they were constructed in eighteenth-century style. Inside the Grand Palace, two ceremonial halls were made and named Catherine's Hall and the Tauride Hall, thus symbolizing the love which united Catherine the Great and her favourite Prince Grigory Potemkin of Tauride who, legend has it, persuaded the empress to build her residence here (see Figure 4). The luxuriant and expensive decoration of these two rooms demonstrates the impressive scope of the project and stands for the wisdom, power and luxury of the Catherinian enlightened absolutism. In the absence of authentic objects, the festive atmosphere is created mostly through symbolic means such as luxurious crystal chandeliers, patterned parquet made of precious wood and exhibits such as busts of philosophers with whom the empress corresponded and busts and paintings portraying her companions. The Tauride Hall's visual centre is marked with the picture of Catherine II and Potemkin attending a celebration in Sevastopol to commemorate the founding of the Russian navy. It is a work of Vassily Nesterenko, the ‘court artist’ of Mayor Luzhkov, known for his numerous realistic paintings on patriotic and religious themes. The ceiling of the hall is decorated with a mural allegorically depicting the victories of the Russian army and navy.

Figure 4: The interiors of the reconstructed Grand Palace: there is gold and grandeur in the Catherine's Hall and the Tauride Hall, and simple décor with elements of gothic style in other rooms. The images at the top left and bottom right come from the website of the Tsaritsyno Museum, www.tsaritsyno-museum.ru/index.php?lang=en.

Catherine's Hall is devoted exclusively to the empress. The abundance of gilding in its decoration is intended to symbolize the new myth of the revived Tsaritsyno. It includes antique-style allegorical bas-reliefs as well as insignia that represent the Russian system of military awards dating back to the eighteenth century, and Catherine's saying ‘Power without the trust of the people does not mean anything’ embossed in gold. The only authentic historical object in these rooms is a statue of Catherine II that used to stand in the meeting room of the Moscow State Duma.

Other rooms in the Grand Palace are decorated using inexpensive modern materials and show considerably less impressive imitations of historic interiors. The entrance area is a glass pavilion that gives access to an underground level, obviously an allusion to the glass pyramid of the Louvre. In front of the palace, a monument was erected for Bazhenov and Kazakov. It shows the two architects standing together with a model of the palace between them, thus completely negating the stylistic conflict between their projects and the history of one palace constructed in the place of and using the bricks of the other. The memory of the ruin phase in the history of Tsaritsyno is also erased.

In the end, Tsaritsyno did become a museum of the eighteenth century. But it barely displays original exhibits and interiors, and even the dramatic history of its own origin in the eighteenth century is represented in an opaque manner. The fate of the empress's residence at the beginning of the twenty-first century presents a historical paradox. The creation of the historical museum and the public recognition of the place as a historical monument were complemented with the deletion of many traces of the past and with the erasing of the differences between authentic and non-authentic objects. The quasi-historical setting was created in the middle of the Tsaritsyno museum area and was intended for the ideological representation of the ‘eternal’ power of the Russian and Moscow authorities. The legend of ‘the Golden Age’ was intended to serve this purpose, in place of historical multidimensionality. Arbitrary reconstruction has negatively affected Tsaritsyno's image in the eyes of experts and of the educated public.

But there were also different forces that influenced Tsaritsyno's reception and that changed this negative attitude in the course of recent history, at least in the eyes of the majority of the park's and museum's visitors. Besides, there had also been factors that did not allow the ideological functions of the museum to work at full capacity. On the contrary, during the years after the restoration, Tsaritsyno has become a vivid and multidimensional place with a comparatively sophisticated attitude to historical edutainment, with a diverse public and with some visible traits of a new communication culture that can be registered as a pattern for other newly reconstructed public spaces in Moscow. We argue that because of its new publics and because of the collective reaction of the publics to ‘situated multiplicity’, the ‘thrown-togetherness of bodies, mass and matter, and of many uses and needs in a shared physical space’Footnote 37 that produce a ‘proper’ contemporary public space, Tsaritsyno has earnt its place in the history of the city's public spaces. It has become a multitemporal place with unique configurations of historical and modern elements, epitomizing Moscow's new publics’ work on the development of the culture of public communication in the city.

These new configurations and new forms of social life in Tsaritsyno are usually neglected in critical statements on the renovated park and museum as an ahistorical place. Meanwhile, when studying the post-‘fantasy restoration’ Tsaritsyno, our main interest was directed to the everyday functioning of this place with its specific historicity, unusual in its combining the functions of a museum, an educational institution, an entertainment facility and a recreational zone. Tsaritsyno, this ‘laboratory of publiс modernity’ and also ‘eighteenth-century theme park’ with multiple ‘attractions’, provided us with compelling material for observations and conclusions upon the development of urban culture in Moscow that will be elaborated upon in the final part.

Photographing the fountain, creating different histories: new urban publics and museum politics in Tsaritsyno

As our sketch of Tsaritsyno's history has shown, the renovation of the park was designed to encourage large numbers of visitors, and crowds were not slow to appear there. While certain concessions were made to advocates of historical authenticity – for example, the winding walking paths in the park were restored, and earthen terraces on the hillside behind the Small Palace were opened the first time since the eighteenth century – many other material, i.e. functional, and stylistic solutions were made that abruptly transferred Tsaritsyno into the present-day reality with its crowds, attractions and entertainment parks. The style of the renovated Tsaritsyno and the materials used in it aroused memories of theme parks and megamalls in visitors. Indeed, these memories remain a permanent background against which people view Tsaritsyno. In talks and online reviews, they describe what they see as ‘Disneyland’, ‘Cinderella Castle’, ‘Hogwarts’, ‘sweet cake’, ‘supermarket’ and ‘Vegas’, meaning not only the city Las Vegas but also ‘Vegas’, a giant city-mall on the Moscow Ring Road not far from Tsaritsyno, which opened in 2010 and is familiar to local residents. The newly built Grand Palace is, of course, especially referred to in these comparisons, but not the Grand Palace alone. For example, in the course of the renovation the whole space around Bazhenov's buildings was covered in paving stones in order to provide access to the museum and free movement for the many visitors over the central part of the reserve. What was supposed to be a purely functional solution in the face of the numerous pedestrians walking on the lawn unexpectedly entered into a complex aesthetic relationship with architecture. The bright decoration of the pavement was so optically expansive that it transformed the visual environment much more than had been expected and, perhaps, was supposed to,Footnote 38 forming a stylistic alliance with the ‘cartoon-style’ green roof of the Grand Palace and its spikes that look like plastic toys, thereby generating and confirming Disneyland associations.

It seems possible to discuss Tsaritsyno as an entertainment facility, or attraction, in two ways: in terms of changes made to the material environment and in terms of radically changing practices and new configurations to be made of this space by new visitors. Of course, these two aspects are complementary and mutually reinforcing. Perhaps the most striking example of a new object-attraction installed in Tsaritsyno during the renovation is the huge light-and-music fountain in the middle of a once peaceful pond. The fountain is 55 metres in diameter, with a jet height of up to 15 metres. Its baroque exuberance is directly proportional to the contestability of its very presence in a landscape park from a historical point of view (see Figure 5). This technological facility was built on a small island in the Middle Tsaritsyno Pond on the personal order of Mayor Yuri Luzhkov, who had a soft spot for city fountains. To that end, the island was expanded, strengthened and equipped with two modern bridges, benches and loudspeakers for music. Neither the idea itself, nor the appearance, nor the use of the fountain which has become a sort of ‘central square’ of the ‘boulevard’ down which visitors walk from the entrance gate to the Grand Palace, remind us of the old ‘romantic’ Tsaritsyno. The space around the fountain is one of the busiest spots in the park.

Figure 5: Light-and-music fountain, the main technological attraction of Tsaritsyno.

This fountain is a typical ‘attraction’ as the theory of visual urban modernity understands it today.Footnote 39 It is a modern spectacle rooted in a more general culture of fairs, amusement parks and early forms of cinema – a culture that gained great importance in European and American cities and in Russia during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with cities rapidly growing, an urban public culture developing and urban public spaces becoming filled with a new type of public that claimed exactly this type of entertainment. This spectacle has a direct effect: surprise, shock, delight and other affects are produced immediately with no requirements set as to training, intelligence or endurance of the viewer/participant. Such attractions (or rides) convey no message; they exist in the here and now; they are pure presentation and intended for the collective admiration of a crowd – the delight is produced when the moments of presence are shared with a company or with passers-by. Researchers also describe the main features of the modern attractions as cyclical work, the rhythmic movement of ornamental light surfaces, repetition and a-narrativity.Footnote 40 The very installation of such a device in a historic space noticeably changes the temporal modes of its perception. The Tsaritsyno fountain is admired. It is endlessly photographed, multiplying its ‘special effects’ in different media. It is contemplated by people spellbound by its cyclic performance and cyclic instrumental supporting music that amplifies its effect.

Following the renovation of Tsaritsyno, the attractions that heighten the intense experience of the moment, the active visual consumption (most manifest in endless picture-taking) and the emotionally upbeat atmosphere of pure entertainment have become essential elements of the local public culture. Events and amusements that stand alongside the fountain in a series of attractions include a successful annual Light Festival, during which the spotlighted palaces and park vegetation function as objects of admiration and wonder, kiting festivals, ballooning over Tsaritsyno, and so forth. In fact, the whole of Tsaritsyno, including its historical content, has become an attraction for the public who conceives of the museum-reserve as a set of rarities and special effects that provide photo opportunities and recreation (see Figure 6). Keeping historical distance is not practised here – on the contrary, the absolute here-and-now effect of rides and attractions, reflected in the title of our book Attraction with History, comes to the foreground. The trajectory and the pace of visitors’ walking on the park paths are determined by their search for good views from which to take pictures and for opportunities to do something; climb up a tower-ruin or a monument, come up with a good shot from an unusual angle, put one's headscarf on a plaster sphinx's head, balance oneself on the remains of eighteenth-century foundations, etc.

Figure 6: Mass visitors invent many ways to use Tsaritsyno as an amusement park.

The general public today mostly use Tsaritsyno as an eighteenth-century theme park, a fact which leaves its mark on the cultural and historical values of this place. Here is a joyous example of how the museum value of the estate and the cultural distance principle lost out to the perception of Tsaritsyno as an attraction. In autumn 2012, Tsaritsyno hosted an exhibition of the works of Auguste Rodin, with small sculptures displayed inside the Grand Palace and large ones cast in bronze outdoors (see Figure 7). In order to emphasize their status as museum objects and regulate the way they were to be treated, the museum staff provided the outdoor sculptures with a sign saying ‘Dear visitors! Thank you for your caring attitude towards these art objects. May we remind you that in museums it is not allowed to touch sculptures or to climb on their pedestals.’ However, visitors, used to non-stop automatic photographing of everything ‘beautiful’ and ‘extraordinary’ they encountered and used to playing or sharing remarks with others during this process, quickly placed Rodin's statues within the series of attractions they were accustomed to consume in Tsaritsyno Park. As a result, throughout the period of the exhibition visitors could be seen touching the sculptures and climbing on their pedestals, grabbing Citizens of Calais’ fingers, putting a wreath of autumn leaves on The Thinker’s head, and other similar activities. They also visibly supported each other in these mischievous acts, to the irritation of older people who are usually more supportive of strict ‘Soviet’ regulation of personal behaviour in a public place.

Figure 7: Auguste Rodin exhibition in Tsaritsyno, 2012.

Faced, on the one hand, with the authenticity deficit issue following the clamorous professional and public criticism of the ‘fantasy restoration’ and, on the other hand, with having to market Tsaritsyno to the broad public within this context and dealing with a new vivid public space instead of quiet ruins, the museum staff opted for a way that is in keeping with today's international trends in museum work. In museum policy, guided-tour programmes and educational activities make a point of acknowledging the changed historical culture of the place and using adequate methods of reaching out to diverse audiences, including multiple up-to-date performative and edutainment activities.Footnote 41 To be sure, this transition is a process that is neither completed nor currently all-encompassing. The trend is, however, clear: the museum abandoned the idea of relying solely on the rigid, ideological imperial ‘Catherine brand’, which involved, among other things, construction of a holistic linear history of Tsaritsyno, and gradually shifted towards much more diverse, multilayered histories and themes presented in modern forms. Even the motto of Tsaritsyno's museum policy changed in 2014, following the appointment of a new director. While the official album-guide released in 2008 was titled ‘Golden Tsaritsyno’,Footnote 42 the new motto reads ‘Projects, fantasies and utopias of the eighteenth century’, which clearly implies attention to the unfulfilled projects of the past and the introduction of ‘virtual realities’ and multiple images of the past as well as of the present in the contemporary visitor's horizon of perception.Footnote 43

The contemporary strategy of the Tsaritsyno museum's presentation to the public involves abandoning the traditional concept of a museum as a store of valuable authentic items which was virtually unopposed in the Soviet epoch for a more up-to-date version of museum edutainment. The space of the Grand Palace and the whole territory of the Tsaritsyno museum operate today as an exerciser for historical imagination. The historian of popular culture Michael Saler describes this mode of modern man's existence in conventional virtual realities as that of the ironic imagination ‘as if’. This, Saler repeatedly stresses, is a profoundly modern mode which emerged with the development of certain genres of popular literature, such as science-fiction, fantasy and detective stories. Its purpose is to combine fantastic and rational comprehension of the complex modern reality.Footnote 44 Neither the guides nor the exhibition at the Grand Palace keep visitors in the dark about the fact that Catherine II never lived in Tsaritsyno and that the Grand Palace is just a modern architectural fantasy. But those who produce the public awareness of Tsaritsyno today write their ‘Tsaritsyno text’ at the junction of rational knowledge and the completely opposite expectations of visitors who seek to join in the luxury of a ‘real’ imperial palace. Forms of such ‘performative historicity’ include theatrical performances on themes from the eighteenth century, theme parties for adults and children in Catherine's Hall, dress-up photography in costumes and wigs of the epoch, historical cuisine workshops, porcelain exhibitions, etc. (see Figure 8). Other epochs of the history of Tsaritsyno also find their way into playful edutainment; in a series of theatrical workshops, schoolchildren become familiar with the dachas period of the history of the place and even with communal living in the Kitchen House during the Soviet era. All of these themed activities are dynamic; they attract great numbers of visitors from different social groups and go a long way towards bringing participants back to history through play, fantasy and, in a broader sense, amusement and attractions.

Figure 8: Performances and edutainment in Tsaritsyno. The images at the top right, bottom left and bottom right come from the website of the Tsaritsyno Museum, www.tsaritsyno-museum.ru/index.php?lang=en.

This multilayered, non-totalitarian historical presentation of the museum goes in accord with the general atmosphere in the park, which is always described by visitors as relaxing, peaceful and inclusive. Through a series of interviews and observations in the park done in 2010–13 and referenced in our book, we discovered that different social groups, such as, for example, older people of modest means or migrant workers find it comfortable, safe and pleasant to relax in the visible ‘throwntogetherness’Footnote 45 of the Tsaritsyno Park alongside active young people, families with children, dance clubs and so on. After the reconstruction, Tsaritsyno gained a role as a citywide public space and made a significant contribution to the formation of a new public communication culture in Moscow. This contribution is often overlooked against the background of a large city and its ongoing transformations. By and large, the public ascribes the leading role not so much to Tsaritsyno as to Gorky Park following its pronouncedly youth-oriented repurposing in the 2000s. Yet our more than three-year-long study of communication culture in Tsaritsyno has shown that due to its historical attractions and rich recreational opportunities Tsaritsyno can be regarded as the first example of a new multifunctional urban public space in Moscow, open to different sorts of urban public.

In terms of turnout, especially on weekends when the weather is fine, Tsaritsyno is comparable to boulevards in downtown Moscow and shopping malls. What makes it different is its communication culture characterized by non-commercial orientation, a low level of conflict and the prominent presence of ‘easy communication’, i.e. distanced and superficial but extremely friendly communication between strangers, which is scarce in post-Soviet metropolises. The park space in Tsaritsyno is supervised in a soft and invisible way typical of theme parksFootnote 46 rather than of museums, especially Soviet-style ones. But, unlike theme parks, no strictly pre-set behaviour scenarios are imposed on visitors, making Tsaritsyno a very comfortable place to spend one's spare time. These factors contributed also to the formation of numerous endemic micro-practices of interaction and facilitated the development of productive communication scenarios and norms. Increased government participation in the public life of Moscow during the last five years is generally perceived as a form of excessive control and is the subject of criticism by Russian civic activists. The Tsaritsyno public culture evolved more freely and continues to develop with the help of grassroots agents and activities including the contributions made by, for example, an amateur Breton dance club whose members come to dance barefoot on the large central lawn and involve all those who happened to be there in their dance. Further examples that may be cited are animals (squirrels, ducks and forester birds) which serve as the most active triggers for ‘easy communication’ between strangers and the Bazhenov-and-Kazakov monument that provides great opportunities for photographic jokes. In this sense, the ‘eighteenth-century theme park’ has really managed to go down in the history of Moscow as a ‘palace and park ensemble for the people’, even if not quite in the sense that was read into this concept by the former mayor of Moscow and his loyal interpreters of the ‘Luzhkov restoration’.Footnote 47