If viewed in isolation, and at face value, the proposal to establish a National Institute for Mental Health in England (NIMHE), supported by nine regional development centres, would seem a good idea (Department of Health, 2001) — a single unified initiative, led by the National Director for Mental Health, to oversee and support the modernisation of English mental health services in line with the National Service Framework (NSF) and latest Government policy. However, the justification for such a development is less clear-cut when the proposal is considered in more detail and in the broader context of other NHS structures and processes.

NIMHE must overcome significant obstacles if it is to achieve its stated aim of playing ‘a key role in implementation and development of mental health policy’ (Department of Health 2001: p. 9). These obstacles are partly structural and relate to the existing system for developing, implementing and monitoring mental health policy, to which NIMHE is being added and within which it must function. They are also to do with the nature and number of the tasks that NIMHE has set itself, how it will be perceived by front-line staff and the future of mental health service funding.

These reservations about NIMHE are best framed as questions.

How does NIMHE fit within the NHS structure?

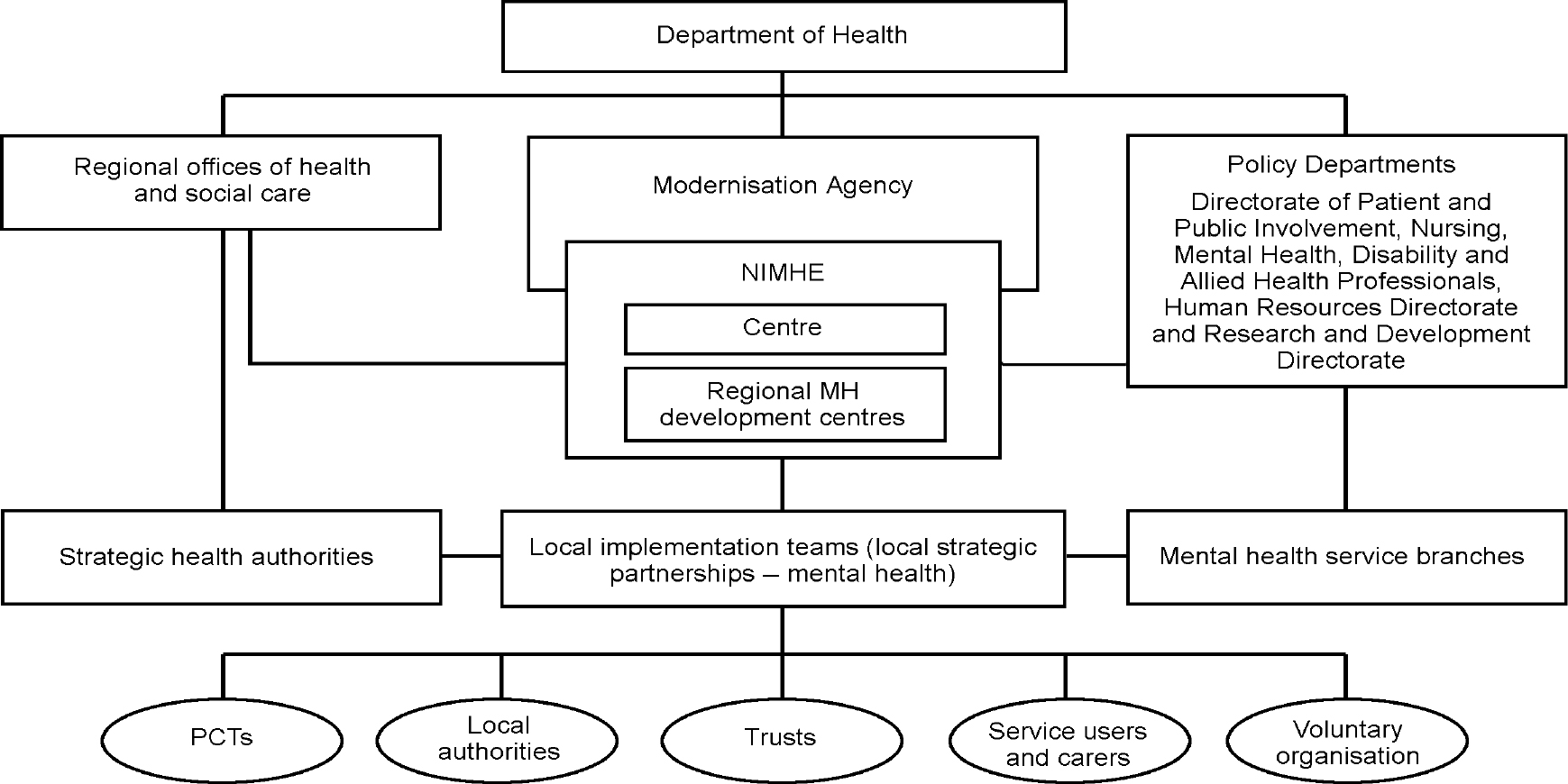

The neat organisation diagram on p9 of the Department of Health consultation document (see Fig. 1) seems to describe a clear set of relationships between structures. NIMHE sits at the centre of the diagram, nestled within the Modernisation Agency. It is presented as having links downwards, through the nine regional development centres and mental health local implementation teams, to service providers and commissioners, and links sideways with the mental health services branch and other policy departments within the Department of Health and with the new regional offices and strategic health authorities.

Fig. 1. NIMHE and its organisational relationships (from Department of Health, 2001. Crown copyright material is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of HMSO and the Queen's Printer for Scotland.)

NIMHE, National Institute for Mental Health in England; MH, mental health; PCTs, primary care trusts. The lines represent lines of communication, not formal accountability. There will of course also be a much wider network of communication links with groups and agencies working with the full range of age groups and special needs.

However, even this simple presentation of relationships contains ambiguities. In terms of upward accountability, NIMHE has two heads. It will be managed by a chief executive who, presumably, will account to the Director of the Modernisation Agency and through him to the Chief Executive of the NHS. It will be ‘led’ by the National Director for Mental Health, who is not strictly a civil servant but a ministerial appointee who reports directly to the Secretary of State. To add to the complexity, the chief executive of NIMHE is also joint head of the mental health services branch of the Department of Health, whose reporting line is through the Chief Nursing Officer.

The establishment of nine regional development centres is consistent with the current structure of the NHS. However, this will not be the case after 2003 when existing regions will be replaced by four regional offices of health and social care.

What authority will NIMHE have to undertake the tasks it has set itself?

The note accompanying the organisation diagram states that, for all connections sideways and downwards, ‘the lines represent lines of communication, not formal accountability’. Thus, NIMHE has no formal relationship with the new regional offices, the strategic health authorities or primary care trusts. The NIMHE centre will not even directly manage its own regional development centres, which are likely to be controlled by regional offices, strategic health authorities and NHS trusts. How will NIMHE implement and develop mental health policy when, in structural terms, it is only one small part of the Modernisation Agency?

Although the Chief Executive and leader of NIMHE, acting in their other capacities, play a leading role in policy making, NIMHE itself appears to have no formally defined relationship with either the policy making or executive arms of the NHS. Its ability to influence these functions will presumably be only as great as the authority borrowed by the NIMHE Chief Executive and the power vested in the National Director for Mental Health and/or the Modernisation Agency by the Secretary of State.

How can such a small organisation achieve such an ambitious remit?

Although vague about the specifics of its activities, the consultation document is hugely ambitious in the scope of the task that NIMHE is taking on. NIMHE ‘will work with all agencies to develop a co-ordinated programme of research, service development and support… it will ensure the development of evidence-based mental health services and take fully into account the wider issues of social inclusion and the development of the communities in which people live and work’ (Department of Health, 2001: p. 3). Furthermore, ‘it will be concerned with mental health care in primary, specialist and tertiary care organisations, in both health and social care… it will cover mental health promotion… [and] will address the issues of adults of working age, older people, children, learning disability, secure and prison health services, and other groups with special needs’ (Department of Health, 2001: p. 5). The regional development centres will undertake service evaluations; training and education; leadership development; the creation and management of networks; act as a resource information service; undertake specific projects; and organise events. All of this will be achieved using a small administrative centre and an annual budget of about £500 000 for each regional development centre.

What will NIMHE or its regional development centres do that does not fall within the remit of some other organisation or part of the NHS?

To those working at the coal-face, the mechanisms by which Government policy is made and implemented can appear uncoordinated and confusing. The question is whether the establishment of yet more semi-autonomous bodies, particularly ones with no clear connections to other parts of the system, is the way to improve this. Also, the piecemeal expansion of the number of central bodies appears at odds with the Government's stated commitment of devolving responsibility to a more local level.

If NIMHE's relationship to other structures and process is not clarified it might achieve the opposite of its stated aim of ‘bringing a new coherence to the overall process of performance management and service development’ (Department of Health, 2001. p. 5). As presented, NIMHE and its development centres appear to run in parallel to other NHS systems. The potential for NIMHE to add to the confusion of those at the bottom of the loosely linked chains of command can be illustrated by referring to how some of NIMHE's possible functions might overlap with, or even duplicate, the work of other bodies.

Modernisation

NIMHE is not even the only part of the Modernisation Agency with a mental health remit. As one of the priorities in the NHS Plan, other programmes of the Modernisation Agency, such as the Leadership Centre, the Clinical Governance Support Team and the National Patients' Access Team, will continue to be active in the field of mental health. Also, the consultation document does not specify the relationship between NIMHE and the Mental Health Taskforce, whose remit is to drive forward the Government's programme of modernisation through implementation of the NHS Plan.

Implementation of mental health policy

With the introduction of NIMHE and its regional development centres, there has been no dismantling of the profusion of other mechanisms for implementing or monitoring mental health policy. The majority of these mechanisms involve new bodies introduced by the current labour government. The functions and interconnections of these are not easy to summarise, but they include:

-

• the four regional offices for health and social care, which will have a remit to oversee the development of local services

-

• strategic health authorities to give a local strategic lead and assure local delivery of health improvement plans

-

• primary care trusts which will build performance management procedures into their commissioning activities

-

• the Commission for Health Improvement (CHI), soon to evolve into the Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection (CHAI), one of whose core functions is to review the implementation of the National Institute for Clinical Excellence guidelines and NSFs. Also, the CHI's Office for Information on Health Care Performance, or its successor, will publish star ratings of NHS trusts

-

• the Social Services Inspectorate and the Audit Commission, which continue to conduct joint reviews of the social services element of local mental health services; at least pending the Audit Commission's incorporation into the CHAI

-

• local implementation teams to implement the NSF

-

• local authority overview and scrutiny committees which will soon have powers to scrutinise local health services. These will spawn joint overview and scrutiny committees to review services to large concentrations of populations

-

• patients' forums in every NHS and primary care trust to monitor and review services. These will report to a new Commission for Patient and Public Involvement in Health, which will set standards and issue good practice guidance about patient and public involvement

-

• the National Patient Safety Agency to review adverse incidents

-

• an independent reconfiguration panel to give the Government independent advice on major service changes.

Training and service evaluation and organisation development

There are already a number of well-established agencies offering this type of support to local mental health services. Indeed, some of these organisations have tendered successfully to manage one or more NIMHE regional development centre(s). Organisations such as the Sainsbury Centre, the Institute for Applied Health and Social Policy (which incorporates the Centre for Mental Health Services Development) and the Health Advisory Service have created a healthy and competitive market-place for specialist consultancy. Presumably, local services wishing to commission such support will still be able to exercise choice and regional development centres will not try to create local monopolies. It remains to be seen what expertise or capacity NIMHE will contribute over and above what is already on offer.

Research

If well managed, the establishment of a NIMHE mental health research network could create a focus for more multi-centre studies. However, some of the proposed functions of the network seem to fall squarely within the remit of the Department of Health Research and Development Directorate — identifying research priorities, forging links with funding organisations, promoting links between research and development and disseminating research findings. Also, these activities seem out of step with the principal stated purpose of NIMHE, which is to reshape services in line with current policy.

Audit and outcomes

The CHI Office for Information on Health Care Performance, and presumably its successor, will publish performance indicators and manage a programme of national clinical audits, both of which will include mental health. The NHS Information Authority has been given the responsibility for the implementation of the mental health minimum data-set.

How will NIMHE be perceived by front-line staff?

NIMHE's placement within the Modernisation Agency, and the leadership role taken by the National Director, make it, in effect, an arm of the Government. Consistent with this, the emphasis of the consultation document is on implementing national policy. This centralist approach and lack of independence might create a perception that NIMHE is not a body that can respond to the needs of local services. This will certainly happen if NIMHE attempts to add any element of performance management to its array of activities.

This is important because NIMHE's success will be judged by the unique impact that it has on those practitioners and managers whose working practices have to be influenced if services are to be improved. Front-line staff will only engage with NIMHE and its development centres if NIMHE staff are perceived as credible and a sensitive balance is struck between the centres' desire to move services in the direction of national policy and respect for the expertise and local knowledge of practitioners. At present there appears to be a strong sense among front-line staff of being put upon from above and of being constantly told how to do their jobs.

Will there ever really be extra money to implement the NHS Plan and NSF?

The new money for mental health services has not yet reached ground level. Although the complexity of the service and financial framework process makes it difficult to follow the funding, the experience of some trusts has been that new service elements, such as assertive outreach teams, have been developed at the expense of existing ones, such as community mental health teams. It would appear that often the combined effect of uplift and ring-fenced new money for NSF targets does not exceed the losses owing to cash releasing efficiencies and cost pressures. The credibility of NIMHE will perhaps be enhanced if there are increases in funding that seem real to those on the ground, so that NIMHE regional development centres are working in a climate of overall service expansion rather than of stasis or even cut-backs.

Although the need for such an initiative can be questioned, now that it exists it is in the interests of mental health services, and of the people who use them, that NIMHE succeeds. Its early priorities should be to define and develop its relationships with the numerous agencies with which it must work, to manage expectations of what it can achieve, and how quickly, down to realistic levels and to win the hearts and minds of front-line staff.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.