I. INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has focussed attention on the appropriate balance between public interests, notably health, and the interests of investors.Footnote 1 This article explores the relationship—at times fraught—between the obligations of host States under International Investment Agreements (IIAs) and their regulatory powers in the field of public health. First, it considers investment case law under existing treaties and examines cases that have directly addressed public health, as well as the legal bases and the tribunals’ reasoning for doing so. Secondly, the article scrutinises the new generation of IIAs and Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) that include provisions dealing with public health in their investment chapters. Thirdly, the article assesses the treaties more broadly: it examines whether past cases would have been decided differently under the new generation of investment treaties, evaluates the relationship between public health measures and intellectual property rights, and discusses a possible alternative to the dominant nexus requirement of ‘necessity’, this being an exception for measures ‘related to’ public health.

In its conclusion, the article investigates how, similar to the incentive model pioneered by the Kyoto Protocol with regard to renewable energy investment, international law could actively promote private investment in furtherance of global public health objectives, for example in the context of a global pandemic.Footnote 2 Such health objectives can be realised only through reasonable regulatory measures that harness the material resources of the global private sector for the purposes of socially beneficial economic activities while also protecting human health.Footnote 3 At present, IIAs and investor–State arbitration remain vital mechanisms of international law which must balance the potentially conflicting objectives of investment protection and public health. The alternative would be to redesign the relationship between these objectives through far-reaching investment treaty reform or a novel agreement on public health.Footnote 4

II. PUBLIC HEALTH IN INVESTMENT DISPUTES UNDER EXISTING TREATIES

Investment treaties concluded before 2015 generally do not refer to public health.Footnote 5 As a result, whenever this has arisen in investment proceedings, it has been left to the arbitral tribunals to weigh public health against the interests that are explicitly protected under the investment treaties. Investor–State arbitral tribunals have dealt with a number of investor claims and host State defences based on public health grounds. Such States include both developed and developing countries, and the grounds invoked relate to a wide variety of public health matters. These grounds are categorised and analysed below as cases where investor interests were arguably pitted against, first, health warnings and plain packaging rules (subsection 1); secondly, measures promoting access to medicine (subsection 2); and, thirdly, environment-related health measures (subsection 3). Catalogued in a Table in subsection 4, these cases comprise all known publicly available decisions that directly address issues of public health, with the obvious caveat that the notion of public health is itself open to debate both as an analytical category and as a question of treaty interpretation.Footnote 6

A. Health Warnings and Plain Packaging Rules

On 21 May 2003, the World Health Assembly adopted the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), the first international agreement negotiated under the auspices of the WHO.Footnote 7 It entered into force on 27 February 2005 and, at the time of writing, has 182 Parties covering more than 90 per cent of the world's population.Footnote 8 The FCTC is intended to be a milestone in the promotion of public health and to further develop the legal framework for international health cooperation. In the wake of this Framework Convention, and in the context of debates taking place at international, regional and domestic levels, several countries moved towards the adoption of so-called ‘plain packaging rules’.

The WHO has defined plain (or standardised) packaging as ‘measures to restrict or prohibit the use of logos, colours, brand images or promotional information on packaging other than brand names and product names displayed in a standard colour and font style (plain packaging)’.Footnote 9 Plain packaging serves several purposes, including ‘reducing the attractiveness of tobacco products; eliminating the effects of tobacco packaging as a form of advertising and promotion; addressing package design techniques that may suggest that some products are less harmful than others; and increasing the noticeability and effectiveness of health warnings.’Footnote 10 In 2012, Australia became the first country to implement laws requiring plain packaging of tobacco products.Footnote 11 Since then, Belgium, Canada, France, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Slovenia, Thailand, Turkey, the United Kingdom and Uruguay have implemented legislation while other countries, including Chile, Ecuador, Panama and South Africa have initiated legislative processes in this regard.Footnote 12

These developments were not, however, universally welcomed: perhaps unsurprisingly, the tobacco industry mounted a counterattack arguing that plain packaging would breach their intellectual property rights and infringe international trade agreements, as well as the EU Principles of Better Regulation.Footnote 13 Moreover, tobacco companies argued that there was no credible evidence that plain packaging would be effective in achieving its stated goals and that many countries had already dropped the idea. Finally, they feared that plain packaging would lead to increased smuggling of counterfeit cigarettes, that it would be costly, and that it would be extended to other products.

Amidst this discussion, one tobacco company, Philip Morris, decided to launch international arbitral proceedings against two States that had imposed restrictive regulations on tobacco packaging: Australia and Uruguay.Footnote 14 Before Australia had adopted its plain packaging rules, Uruguay had already enacted an Ordinance requiring each cigarette brand to have a ‘single presentation’ and prohibiting different packaging or ‘variants’ for cigarettes sold under a given brand, as well as a Decree imposing an increase in the size of the health warnings on the surface of the cigarette packages from 50 per cent to 80 per cent, leaving only 20 per cent of the cigarette pack for trademarks, logos and other information. These cases stand out as they rank among the very few investor–State arbitration cases that have ever been instigated against legislation (as opposed to single instances of implementation or administrative acts).Footnote 15 Both cases were, however, roundly rejected by the respective investor–State tribunals—albeit on different grounds.

Philip Morris v Australia concerned a dispute brought by Philip Morris Asia Limited (the regional headquarters of Philip Morris International) under the Hong Kong–Australia Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) (1993) against Australia on the basis of the latter's enactment and enforcement of the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act (2011). Philip Morris claimed that the legislation violated intellectual property rights relating to tobacco products and packaging, resulting in an indirect expropriation which had the effect of substantially diminishing the value of its investments in Australia. More specifically, the Claimant argued that the Act was in breach of the prohibition on expropriation and the obligation to provide fair and equitable treatment (FET).Footnote 16 The Tribunal did not examine the merits of this argument, because it deemed the claim inadmissible: the commencement of proceedings was viewed as an abuse of process because the corporate restructuring of Philip Morris Asia had occurred when there was already a reasonable prospect that the dispute would materialise.Footnote 17 In other words, the Tribunal considered that the investor had changed its corporate structure for the very purpose of starting investment arbitration proceedings. As a result, the claim failed at this jurisdiction hurdle.

The Philip Morris v Uruguay case was initiated by Philip Morris Brand Sàrl (PMB) (the Swiss subsidiary of Philip Morris International) and two affiliates under the Switzerland–Uruguay BIT (1991) on the basis of Uruguay's treatment of the trademarks of its cigarette brands. Two of the host State's measures were contested: its Single Presentation Requirement (SPR), which permitted only one variant of cigarette per brand, and its 80/80 Regulation, which increased the size of graphic health warnings on cigarette packages to 80 per cent (front and back).Footnote 18 Again, the Claimants argued that the host State's measures violated both the expropriation and FET standards.Footnote 19 In addition, the Claimants alleged that their rights to use and enjoy their investments had been impaired and that the host State had failed to observe its commitments concerning the use of trademarks and had committed a denial of justice.Footnote 20

The Tribunal dismissed the claim, holding that indirect expropriation does not occur ‘as long as sufficient value remains after the Challenged Measures are implemented’, while a partial loss does not constitute expropriation.Footnote 21 Moreover, the Tribunal offered an additional reason for dismissing the claim of indirect expropriation, namely that the challenged measures were ‘a valid exercise of the State's police powers’ with the consequence of defeating the claim for expropriation under Article 5(1) of the BIT.Footnote 22 The Tribunal integrated the police powers doctrine as a relevant rule of general international law in its interpretation of the BIT, but also relied on Uruguay's obligations under the FCTC—‘guaranteeing the human rights to health’—and the WHO's amicus curiae brief in determining that the impugned measures were potentially an effective means of protecting public health and thus a reasonable exercise of regulatory power.Footnote 23 Concerning the FET claim, a majority of the Tribunal found there had been no breach of the Claimants’ ‘legitimate expectations’ nor of the ‘stability of the legal framework’.Footnote 24 Again, the majority placed weight on Uruguay's pursuit of its obligations under the FCTC and the evidence submitted by the WHO in concluding that the measures were not arbitrary.Footnote 25 The majority also agreed with the Respondent that the ‘margin of appreciation’ is not limited to the context of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) but ‘applies equally to claims arising under BITs’, at least in contexts such as public health.Footnote 26

In relation to the SPR, the Tribunal held that what mattered was not the effect of the measure but whether it was a ‘reasonable’ measure when it was adopted, that it was not disproportionate and that it was adopted in good faith.Footnote 27 It decided that the SPR was indeed a reasonable measure, not arbitrary, grossly unfair, unjust, discriminatory or disproportionate, and that this was especially so considering its relatively minor impact on the Claimants’ business.Footnote 28 The Tribunal found that substantial deference was due to governments in this regard, as ‘[s]ome limit had to be set, and the balance to be struck between conflicting considerations was very largely a matter for the government’.Footnote 29 The question was whether the 80 per cent limit was ‘entirely lacking in justification or wholly disproportionate’—and the Tribunal decided it was not.Footnote 30 As a result, the 80/80 Regulation was found to be a reasonable measure adopted in good faith.Footnote 31

In sum, two investor–State tribunals, populated by different arbitrators, operating independently of each other and under different BITs, reached the same outcome (a win for the respective host States) albeit on different grounds: either because the Claimants had committed an abuse of process in bringing the claim (Philip Morris v Australia) or because public health considerations prevailed on the merits (Philip Morris v Uruguay).Footnote 32 As an additional win for Uruguay, the latter Tribunal even awarded the Respondent 7 million USD to cover the costs of its defence.

The tobacco industry also fought the point in different fora, supporting Honduras, the Dominican Republic, Cuba and Indonesia in bringing cases before the WTO Dispute Settlement Body against Australia,Footnote 33 alleging that its plain packaging rules violated the Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) Agreement, the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs) and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)—but again a panel found that no violation had been committed.Footnote 34 These findings were upheld on appeal.Footnote 35 Together, the trade and investment jurisprudence suggests that regulatory caution in respect of the tobacco industry may at least be partly driven by domestic decision-makers’ lack of appreciation of how seriously international trade and investment adjudicators take the protection of public health.Footnote 36

B. Access to Medicine

A second category of cases where investment protection and public health interact also relates to intellectual property, but this time involves issues relating to patent protection, which may clash with access to medicine and health care. One of the earliest cases on record is Signa v Canada, where a notice of intent was registered in March 1996 when a manufacturer of generic pharmaceutical products sought to challenge the duration of patents.Footnote 37 The investor claimed that a longer duration frustrated the legitimate expectations of Article 1105 of NAFTA, but the case soon settled for confidential reasons.Footnote 38

A case concerning the regulation of health insurance, Achmea v Slovak Republic, was initiated under the Dutch–Slovak BIT in 2008. It dealt with regulatory measures which included a ban on profits and transfers that allegedly constituted a ‘systematic reversal of the 2004 liberalisation of the Slovak health insurance market’.Footnote 39 The investor (a Dutch insurer) had relied upon this liberalisation and its reversal arguably destroyed the value of its investment, which could neither generate profits nor be sold. Allegedly, this resulted in, inter alia, an indirect expropriation and a breach of the FET standard.Footnote 40 The Claimant argued that, as the Slovak Constitutional Court had found in 2011 that the ‘ban on profits’ was unconstitutional, this ‘effectively established a breach of the BIT’, and so compensation was due for the period in which the ban was in force.Footnote 41 The Respondent argued that its accession to the EU in May 2004 terminated the BIT or, at least, rendered its arbitration clause inapplicable. The Tribunal chose to follow the argument of the Claimant and ordered the Slovak Republic to pay EUR 22.1 million in damages.Footnote 42 However, the case should be considered less a ‘victory’ for investment protection over public health considerations, and more a preference for one health insurance regulation over another within the context of a conflict between EU and international law and jurisdiction.

The third case is Apotex v USA, which concerned pharmaceutical imports and sales under NAFTA and the US–Jamaica BIT.Footnote 43 In 2009, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had placed Apotex's Etobicoke and Signet facilities on ‘Import Alert’ in the aftermath of a failed inspection. The FDA signalled that since the drugs from those facilities were adulterated the products could be detained at the US border without physical examination.Footnote 44 As a result, Apotex's US business was decimated, with 80 per cent of its supplies cut off from Canada, causing losses of over USD 500 million. Subsequently, Apotex recalled the adulterated drug products from the US market, hired third-party consultants to help bring its facilities into compliance with US law and promised to overhaul its operations, management structure, and quality control systems. In 2011, the FDA decided to lift the Import Alert.Footnote 45 The Claimants asserted that the US had violated its most-favoured-nation and national treatment obligations (because allegedly, no US investor or investment had ever been subjected to a measure as severe as the Import Alert imposed on the Apotex companies) as well as the FET standard.Footnote 46 The Tribunal dismissed the case on the merits because it did not consider Apotex ‘in like circumstances’ as the domestic comparators, without basing any of its reasoning on public health policy.Footnote 47

The fourth case is Melvin Howard v Canada, which concerned medical (surgical) services and the planned construction of a private healthcare facility. A range of legislative and administrative measures allegedly impeded the completion of the project, causing ‘numerous set-backs’ through zoning requirements and other legal hurdles.Footnote 48 The Claimants allegedly suffered ‘a major loss’ because the Respondent's actions caused their medical technology to be shipped back to the US, in breach of the Canada's obligations in relation to expropriation, most-favoured-nation and national treatment, the minimum standard of treatment and FET.Footnote 49 Before the proceedings on jurisdiction and merits had started, however, the case was terminated because the Claimants failed to pay the deposit.Footnote 50

Fifth, in Les Laboratoires Servier v Poland, a drug manufacturer initiated arbitral proceedings against Poland in a dispute concerning the revocation of marketing authorisation of medicines. Rejecting Poland's argument that the revocation was justified under the police powers doctrine, the Tribunal held that the revocation constituted an indirect expropriation and was disproportionate, discriminatory and ‘not a matter of public necessity’.Footnote 51 As the publicly available arbitral award is heavily redacted, the exact role, if any, of public health in the discussion is unclear. Significantly, the Tribunal found that the burden ‘falls onto the Claimants to show that Poland's regulatory actions were inconsistent with a legitimate exercise of Poland's police powers. If the Claimants produce sufficient evidence for such a showing, the burden shifts to Poland to rebut it.’Footnote 52

The claims in the sixth case, Eli Lilly v Canada, arose from the invalidation of the Claimant's Canadian patents protecting the drugs marketed in Canada as Strattera and Zyprexa.Footnote 53 The domestic courts had invalidated these patents on the ground that they did not meet the requirement that an invention be ‘useful’, in accordance with the so-called ‘promise utility doctrine’.Footnote 54 The Claimant asserted that, by adopting this doctrine, the Canadian courts had dramatically altered the application of the relevant provision in the Patent Act, which it considered to be inconsistent with Canada's obligations related to patent protection under NAFTA, and more precisely the prohibition on expropriation and the FET standard.Footnote 55 The Tribunal found, however, that such ‘dramatic transformation of the utility requirement in Canadian law’ was not supported by the facts,Footnote 56 nor by a comparative analysis with other jurisdictions.Footnote 57 It concluded that the Claimant had not met its burden of proving a violation of legitimate expectations.Footnote 58 The other claims alleging the arbitrary and discriminatory character of the utility requirement were equally dismissed.Footnote 59

In sum, these cases illustrate the range of techniques available to investment tribunals in reconciling ostensible conflicts between the economic and public health interests. In Signa v Canada, the Claimant was a manufacturer of generic medicine who argued that the duration of patents should be more limited than was provided for in Canadian law. More limited patent duration is one of the main demands of those who advocate wider access to medicines and who would thus have found themselves on the side of the investor in this case.Footnote 60 The Achmea award arguably dealt with a clearer conflict between investment and public health, assuming that the measures requiring the Claimant to reinvest its profits would have yielded benefits to Slovak healthcare rather than disincentivising new investment. However, the dispute ultimately turned on a jurisdictional conflict between EU and international law. Equally, in Apotex, the choice was not between investment protection or access to medicine, but rather whether a case that was essentially a trade dispute (concerning medical drugs import) could be brought under an investment agreement.

In Melvin Howard and Eli Lilly, if anything, the investors were advocating in favour of increased access to medicine: in the former, for the sale of medical services and the construction of a healthcare facility; in the latter, for the patenting of new drugs. Some argue that the existence of a patent as such restricts access to medicine (and any IIA protecting patents as investments would therefore also restrict access),Footnote 61 but if so, the problem lies not with investment law, but rather with the global and domestic protection of intellectual property rights.Footnote 62 As the Melvin Howard case was terminated before any written submissions on behalf of the Canadian government had been made, it is impossible to say whether the government would have sought to defend its actions on public health grounds. In order to defend itself in Eli Lilly, the Canadian government chiefly relied on procedural grounds (eg lack of jurisdiction ratione temporis) and on the argument that there had been no dramatic change in Canadian courts’ interpretation of the requirement under domestic patent law that an invention be ‘useful’. In other words, the Canadian government focused on a legal-technical defence, rather than invoking substantive arguments based on public health—and was successful. What is important, however, is that this case law analysis shows that tribunals have consistently aimed to interpret investment law in ways which avoid, minimise or eliminate potential conflicts between the economic interests of the healthcare industry and access to medicine.

C. Environment-Related Health Measures

A third and final category of cases where the protection of investments and public health could potentially clash are disputes involving environment-related health measures (for example relating to landfills, food safety and water distribution) which could be perceived as impinging upon economic interests.Footnote 63 One of the earliest cases in which this potential clash resulted in an investor–State dispute was Ethyl v Canada, which concerned a Canadian ban on inter-provincial trade of the fuel additive methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl (MMT), which Canada argued was a highly toxic substance that could cause neurological defects and other public health risks.Footnote 64 As this case was settled between the parties, it is impossible to know how a tribunal would have weighed the diverging interests at stake.

Secondly, the Claimant initiated the Tecmed v Mexico case on the grounds that municipal, state and federal actions, including the decision by the Environmental Protection Agency to deny renewal of the Landfill Permit and order its closure, violated Mexico's obligations under the Spain–Mexico BIT. The Tribunal considered it significant that the ‘violations [of which the investor had been accused by the government] did not compromise the condition of the environment, the ecological balance or the health of the population’.Footnote 65 As a result, the Tribunal concluded that the Respondent's actions were driven by ‘sociopolitical concerns’ because none of the actors involved had expressed any concerns that there was a ‘danger that the Landfill may pose to public health, ecological balance or the environment’.Footnote 66 Had such a danger been demonstrably present, the Tribunal may not have held that Mexico had expropriated Tecmed's investment and violated the FET standard.

Thirdly, the investment in AWG v Argentina consisted of a shareholding in a local company that held a concession for water distribution and wastewater treatment services in Buenos Aires and surrounding municipalities.Footnote 67 Faced with claims regarding its alleged failure or refusal to apply previously agreed adjustments to the tariff calculation and adjustment mechanisms, Argentina invoked a necessity defence under customary international law. At this point, the Tribunal recognised that ‘[t]he provision of water and sewage services to the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires certainly was vital to the health and well-being of nearly ten million people and was therefore an essential interest of the Argentine State’.Footnote 68 The defence nevertheless failed as the Tribunal established that Argentina could have satisfied its essential interest through alternative measures.

Fourthly, the first seminal case to go into the merits of the discussion on environment-related health measures was Chemtura v Canada.Footnote 69 Here, the investor claimed that a ban on ‘lindane’, a pesticide used in farming which allegedly had negative effects on human health, formed an indirect expropriation under Article 1110 of NAFTA. The Tribunal found, inter alia, that, even if the ban had caused a substantial deprivation of the Claimant's investment, ‘there was still no expropriation because the [government's] decision to phase out all agricultural applications of lindane was a valid exercise of Canada's police powers to protect public health and the environment’.Footnote 70 Foreshadowing the approach in Philip Morris v Uruguay, the Tribunal accepted that a ‘margin of appreciation’ is relevant to its assessment of the FET standard, but that an investigation of how ‘certain agencies manage highly specialized domains involving scientific and public policy determinations’ must be conducted ‘in concreto when assessing the specific measures’.Footnote 71 Moreover, and akin to Uruguay's pursuit of its obligations under the FCTC, the Tribunal in Chemtura found that Canada's review of lindane was undertaken in good faith as a result of its obligations under multilateral environmental agreements.Footnote 72

A fifth relevant case was Gallo v Canada,Footnote 73 which dealt with water contamination due to mine waste disposal. The US investor argued that Canada had violated Articles 1105 (FET) and 1110 (expropriation) of NAFTA when it enacted the Adams Mine Lake Act which prohibited waste disposal at the Adams Mine site, revoked environmental and operational permits, retroactively banned certain agreements and retroactively extinguished the investor's causes of action under Canadian law. Again, it is impossible to know how the Tribunal would have assessed the public health versus economic interests, because the case was decided in favour of Canada on jurisdictional grounds.Footnote 74

Sixth, in Roussalis v Romania, the claims arose out of disagreements between the investor and the host State relating to the purchase of shares in a large frozen food warehousing facility, tax liabilities and penalties imposed on the investor, and the enforced closure of its operation due to the alleged failure to comply with EU-mandated food safety regulations.Footnote 75 Regarding the latter, the Tribunal was clear: the Respondent's regulatory measures ‘were justified by an important public safety purpose, namely, serious public health and safety considerations’,Footnote 76 indeed:

… food and safety policies are commonplace in many countries and promote an important public safety purpose, namely public health. Each of the State authorities’ decisions was motivated in regard to these food and safety regulations. The Tribunal is therefore not convinced at all that the control actions and the subsequent decisions of the tax authorities were aimed at blocking the activity of the company.Footnote 77

A seventh, atypical, case—Allard v Barbados—saw an investor relying on environmental health grounds in order to hold the government of Barbados accountable for a raw sewage spill which had contaminated a nature sanctuary.Footnote 78 The State had failed to repair a sluice gate, neglected to reduce the run-off of contaminants into the sanctuary and omitted to enforce its own Marine Pollution Control Act. The dispute concerned whether this conduct had caused such degradation to the environment at the sanctuary as to render its operation as an ecotourism attraction impossible or financially unsustainable, justifying closure. The Tribunal found that because ‘Mr. Allard remain[ed] the owner of the Sanctuary grounds, on which he continue[d] to operate a café […], [i]t is therefore undisputed that the Claimant has not been deprived of his entire investment in Barbados’.Footnote 79 The investor had argued that what had been expropriated was not so much the land itself, but rather his ability to run an eco-tourism business on this land. The Tribunal, however, concluded that even if it were to accept that the destruction of the environment could constitute indirect expropriation, the Claimant had failed to establish that he had closed his business due to the contamination.Footnote 80

Finally, a similar type of investment as in AWG was at issue in Urbaser v Argentina, which concerned a minority shareholding in an Argentinean vehicle company that held a concession for the provision of drinking water supply and sewerage services in Buenos Aires.Footnote 81 The investors alleged that Argentina had unlawfully interfered with the tariff regime applicable to the investment and violated various provisions of the concession agreement through the enactment of emergency measures during the 2001–02 financial crisis. The Tribunal confirmed the importance of public health considerations, highlighting the State's prerogatives in terms of ‘protecting public health’.Footnote 82 However, since public health considerations did not play a crucial role in the parties’ arguments in the dispute, the Tribunal did not elaborate further.Footnote 83

Other investment arbitrations concerning environmental issues include Methanex v USA and SD Myers v Canada, in which the respective tribunals had to decide on the lawfulness of a ban on methyl tertiary butyl ether (MTBE) due to concerns regarding groundwater contamination and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) exportation. In the former case, the Tribunal held that the ban constituted a bona fide policy to protect not only the environment but also general public health.Footnote 84 The SD Myers Tribunal dismissed Canada's claim that the export ban was aimed at protecting the environment and found that it mainly shielded the Canadian PCB disposal industry from competition.Footnote 85

In sum, when faced with a clash between environment-related measures to protect public health and economic interests, some cases have been settled by the parties before an award was issued (Ethyl) or were won by the host State on jurisdictional grounds (Gallo). Where the tribunals did go into the merits of the issue (Chemtura, Roussalis and AWG), they have held that the State's police powers in protecting public health prevailed, provided that good governance standards (such as due process, science-based decision-making, non-discrimination, necessity, proportionality and good faith) were respected. Tribunals have determined these good governance standards by reference to a State's pursuit of its international health or environmental obligations (Chemtura). Where public health or environmental grounds were considered to be absent or largely unfounded (Tecmed and, indirectly, Urbaser), the actions of the States were subject to closer scrutiny. Finally, Allard was an atypical case as it related to protection of the environment (at least, from a ‘polluter pays’ perspective) in which the polluter in question was not the investor but the State—a reversal of the usual roles.Footnote 86 The Tribunal, however, applied a rather strict causation test, focusing on whether the environmental damage had directly caused the closure of the sanctuary (as the polluted grounds could still be used for purposes other than eco-tourism), so the investor lost.

D. Interim Conclusion

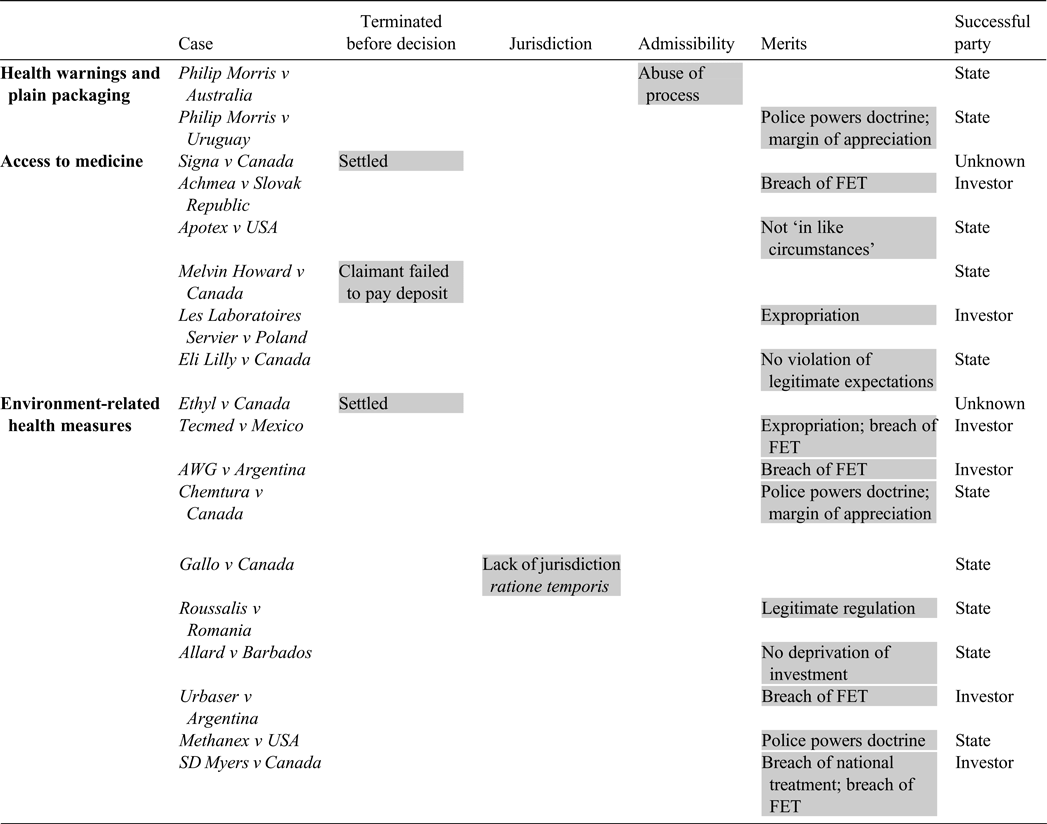

The Table below summarises the 18 investment disputes surveyed above, highlighting the phase at which the dispute was resolved and on what basis. The State prevailed in 10 out of the 18 cases, two were settled, and the investor prevailed in six.

Table. Public health in investment disputes under existing treaties

Successful party (sum/18): State (10/18); investor (6/18); unknown (2/18)

The foregoing survey of the case law does not suggest that tribunals overwhelmingly sided with the claimants in any of the areas addressed. Rather, by and large, they seem to have taken public health into consideration when it was invoked and frequently accepted it as an important policy objective of host States. The widespread perception of investment treaties as riding roughshod over health concerns therefore finds little support in a careful appraisal of how such treaties have been interpreted and applied by past tribunals. Moreover, some well-known dissenting opinions demonstrate arbitrators’ increased sensitivity to the wider legitimacy crisis faced by international investment law,Footnote 87 especially in cases concerning environmental issues.Footnote 88 Preliminary empirical work suggests, however, that arbitrators are generally more responsive to the preferences of influential States than the diffuse signals of public opinion (the latter rather influences States’ future treaty-making activities).Footnote 89

The significant criticism attracted by the Philip Morris cases, for instance, was translated into investment treaty policy by a large bloc of States through the express option to deny the benefits of investment protection for tobacco control measures in the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the forerunner to Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).Footnote 90 While tribunals adjudicating the Philip Morris disputes were doubtless aware of that development, their arbitral reasoning nevertheless relied on positive legal footholds to shore up their recognition of health policy, such as the FCTC and the confirmation of the police powers doctrine in recent treaties.Footnote 91 However, an overreliance on less textually grounded techniques of treaty interpretation, such as the principle of systemic integration, would expose tribunals to the opposite criticism that they are eliding the restrictions on regulatory powers to which States have consented in order to attract foreign investment.Footnote 92 In other words, the more legitimate and predictable avenue for States to signal their policy preferences and legal intentions to international tribunals is through precise and detailed treaty drafting, even if they seek simply to codify a balance between investment protection and public health that has been struck through adroit interpretation of older treaties.Footnote 93

III. PUBLIC HEALTH IN THE NEW GENERATION OF INVESTMENT TREATIES

The ‘first generation’ of investment treaties (roughly, those concluded between 1959 and 2010) did not generally contain any reference to public health, or even human rights, or environmental protection more broadly.Footnote 94 As a result, several investment tribunals have had to assess alleged violations of investment protection standards, which respondent States claimed were justified because of public health reasons, without any guidance from the treaty upon which their jurisdiction was founded. As discussed above, in nearly all of these cases, tribunals have nevertheless allowed public health reasons to prevail over investment interests.

Gradually realising that investment law does not operate in a vacuum, States have started to include references to human rights and the environment, or even to public health directly, in the ‘new generation’ of investment treaties and model BITs (IIAs and FTAs drafted after 2010). Some treaty instruments exclude measures concerning public health from the ambit of dispute settlement altogether. As an illustration, the CPTPP specifically refers to the adoption of measures concerning public health, as will be discussed below (sections 2–4), and does not allow investors to initiate proceedings concerning the legality of tobacco control measures.Footnote 95 While this new generation of investment treaties does not depart radically from the manner in which the dual objectives of protecting foreign investment and public health have hitherto been reconciled in practice through treaty interpretation, by referring to general international law, and more technical defences, these treaties nevertheless represent a step toward greater legal certainty for States and investors alike.

A. A Broad Spectrum of New Treaties

Modern IIAs, including Model BITs, can be categorised based on whether and to what extent they incorporate references to public health, and they display a broad spectrum of treaty-drafting options. This spectrum runs from recent agreements that do not contain any mention of public health, such as the Nicaragua–Iran BIT (2019), to treaties that contain a comprehensive series of references to public health, such as the Norwegian Model BIT (2015). The latter includes no less than eight references to public health, together with a range of other public interest objectives: in its Preamble and its articles on national and most-favoured-nation treatment (Article 3), expropriation (Article 6), performance requirements (Article 8), prohibition on the lowering of standards (Article 11), right to regulate (Article 12), and the Joint Committee (Article 23). For example, the footnote to the national treatment standard provides as follows:

The Parties agree/ are of the understanding that a measure applied by a government in pursuance of legitimate policy objectives of public interest such as the protection of public health, human rights, labour rights, safety and the environment, although having a different effect on an investment or investor of another Party, is not inconsistent with national treatment and most favoured nation treatment when justified by showing that it bears a reasonable relationship to rational policies not motivated by preference of domestic over foreign owned investment. [Emphasis added.]

In particular, the connection between public health and performance requirements is innovative: ‘[a] measure that requires an investment to use a technology to meet generally applicable health, labour rights, human rights, safety or environmental requirements shall not be construed to be inconsistent with paragraph 1 of this Article.’Footnote 96 Public health is not only a prominent reason to deny a finding of discriminatory treatment or expropriation, but the Norwegian Model BIT (2015) also contains a warning to States that ‘it is inappropriate to encourage investment by relaxing domestic health, human rights, safety or environmental measures or labour standards’.Footnote 97 Finally, it is part of the Joint Committee's duties to ‘discuss issues related to corporate social responsibility, the preservation of the environment, public health and safety, the goal of sustainable development, anticorruption, employment and human rights’.Footnote 98

Virtually all recent Model BITs, such as the Indian Model BIT (2015) and the Dutch Model BIT (2018), contain some form of reference to public health,Footnote 99 as do many newly concluded BITs and FTAs with an investment chapter. Often public health is stated as an objective in the Preamble, for example the Dutch Model BIT (2018) stipulates:

Considering that these objectives can be achieved without compromising the right of the Contracting Parties to regulate within their territories through measures necessary to achieve legitimate policy objectives, such as the protection of public health, safety, environment, public morals, labour rights, animal welfare, social or consumer protection or for prudential financial reasons. [Emphasis added.]

The Dutch Model BIT (2018) repeats this public health reference in subsequent articles, but doubts could arise as to the effect of such a reference if a treaty were to only include public health in its Preamble. Typically, preambles are ‘regarded as legally non-binding or, more accurately perhaps, as not giving rise to enforceable rights and obligations’.Footnote 100 It would hence be more difficult for a respondent State to successfully rely on a public health defence based solely on a treaty Preamble.

B. Public Health as Part of the ‘Right to Regulate’

States have the right to regulate all matters in the territory under their effective control. This right does not need to be recognised in any treaty—it is part and parcel of what it means to be ‘a State’.Footnote 101 States might voluntarily limit their sovereign rights through the conclusion of particular treaties (for example, parties to the European Convention on Human Rights have to abolish the death penalty),Footnote 102 but the default position is that wherever a right to regulate with regard to a specific issue has not been explicitly restricted through an international commitment, that State retains its full regulatory rights. As already observed two decades ago:

Nothing in the language of BITs purports to undermine the permanent sovereignty of States over their economies. It is, indeed, arguable that as a matter of international law the right of States to regulate their economies cannot be entirely alienated.Footnote 103

Nevertheless, it was felt in some quartersFootnote 104 that this right to regulate needed to be made explicit in investment treaties, but there is some divergence in the wording. For example, the Norwegian Model BIT (2015) states that:

Nothing in this Agreement shall be construed to prevent a Party from adopting, maintaining or enforcing any measure otherwise consistent with this Agreement that it considers appropriate to ensure that investment activity is undertaken in a manner sensitive to health, safety, human rights, labour rights, resource management or environmental concerns.Footnote 105 [Emphasis added.]

This formulation, variations of which appear in several IIAs, does nothing more than reaffirm the primacy of the investment agreement in instances of tension with the right to regulate,Footnote 106 although similar wording has had some interpretative relevance in the context of environmental measures.Footnote 107 The preamble of the Canada–United States–Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) focuses even more on the fact that a treaty is meant to steer, to some extent, States’ exercise of their regulatory power, as States Parties ‘recognize their inherent right to regulate … in accordance with the rights and obligations provided in this Agreement’.Footnote 108 An earlier version of the Preamble read that the parties affirmed the ‘inherent right to regulate and resolve to preserve the flexibility of the Parties to set legislative and regulatory priorities, in a manner consistent with this Agreement’,Footnote 109 which ‘essentially requires government measures to abide wholly with the rules set out in the [CUSMA]’.Footnote 110 Arguably, such a disclaimer could be perceived as giving preference to the rights and obligations under the IIA, since public health measures have to be taken in accordance with the IIA—which begs the question: what if they are not?

Such disclaimers were not included in a number of other treaties, such as the investment chapter of the EU–Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), which states that:

For the purpose of this Chapter, the Parties reaffirm their right to regulate within their territories to achieve legitimate policy objectives, such as the protection of public health, safety, the environment or public morals, social or consumer protection or the promotion and protection of cultural diversity.Footnote 111

Similar provisions were included in the EU–Singapore Investment Protection Agreement (IPA) and the EU–Vietnam IPA.Footnote 112 Legally, it is doubtful whether the inclusion of such provisions (with or without disclaimers) adds anything to the existing rules and methods of interpretation, but it was viewed as politically important.Footnote 113 However, Article 7 of TRIPS, entitled ‘objectives’ and couched in similar terms, was relied upon by the WTO Panel in Australia—Tobacco Plain Packaging with a view to ascertaining the circumstances in which the use of a trademark is ‘unjustifiably encumbered’ under Article 20 of TRIPS. For the Panel, Article 7 (together with Article 8, on ‘principles’) ‘set out general goals and principles underlying the TRIPS Agreement, which are to be borne in mind when specific provisions of the Agreement are being interpreted in their context and in light of the object and purpose of the Agreement’.Footnote 114 This suggests that adding policy objectives to treaties, such as protecting public health, may play a role in the interpretative exercise of some adjudicatory panels.

Rather than excluding investments in certain industries, such as tobacco manufacturing, through carve-outs (as was, for example, proposed by Malaysia in the CPTPP negotiations), treaty drafters across the globe seem to opt for the inclusion of general or article-specific exceptions in case of origin-neutral, science-based public health measures.Footnote 115 Under the final text of the CPTPP, however, a Party may elect to deny the benefits of Section B of Chapter 9 (Investment) (ie the provisions concerning investor–State dispute settlement, not the substantive obligations) with respect to claims challenging tobacco control measures.Footnote 116 Finally, an innovative provision in this regard can be found in the CPTPP Preamble, which not only refers to Parties’ ‘inherent right to regulate and resolve to preserve the flexibility of the Parties to set legislative and regulatory priorities, safeguard public welfare, and protect legitimate public welfare objectives, such as public health’ but also ‘their inherent right to adopt, maintain or modify health care systems’.Footnote 117

C. Public Health as Part of a General Exceptions Article

One of the major choices to be considered by treaty drafters is whether to refer to public health in a general exceptions article, or to insert such a reference in individual substantive articles, or both. Canada seems to prefer the former option, as seen with the general exceptions provisions in the Canada–Moldova BIT (2018) and CETA. In its General Exceptions Article under Chapter 28, CETA provides that:

For the purposes of […] Sections B (Establishment of investment) and C (Non-discriminatory treatment) of Chapter Eight (Investment), Article XX of the GATT 1994 is incorporated into and made part of this Agreement. The Parties understand that the measures referred to in Article XX (b) of the GATT 1994 include environmental measures necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health. […]Footnote 118

A similar provision is included in the Chapters on ‘Exceptions and General Provisions’ of CUSMA and CPTPP, with specific reference to GATT Article XX(b) and GATS Article XIV(b).Footnote 119 A slightly different focus can be found in the Indian Model BIT (2015), which has a general exception for ‘measures of general applicability’ which ‘ensur[e] public health and safety’.Footnote 120 Several treaty drafters have opted for a mixed system, again illustrated by the Indian Model BIT (2015) which contains a general exceptions article as well as references to public health in its provisions on national treatment and expropriation;Footnote 121 and CUSMA, which refers to public health in the general exceptions article as well as in the provisions on the scope of the investment chapter, expropriation, performance requirements and ‘investment and environmental, health and other regulatory objectives’.Footnote 122 Also, the EU–Vietnam IPA includes public health as one of the general exceptions, in addition to specific references in the articles on ‘Investment and Regulatory Measures and Objectives’ and expert reports,Footnote 123 whereas the EU–Singapore IPA only contains a reference in the Preamble, and in its provisions on investment and regulatory measures, national treatment and taxation.Footnote 124

D. Public Health as Part of Article-Specific Exceptions or Carve-outs

An alternative approach is the sole incorporation of specific exceptions which apply to a single article rather than to the entirety of an agreement. This appears to be the preferred option of the EU, as seen for example within the National Treatment article of the EU–Singapore IPA:Footnote 125

Notwithstanding paragraphs 1 and 2, a Party may adopt or enforce measures that accord to covered investors and investments of the other Party less favourable treatment than that accorded to its own investors and their investments, in like situations, subject to the requirement that such measures are not applied in a manner which would constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination against the covered investors or investments of the other Party in the territory of a Party, or is a disguised restriction on covered investments, where the measures are: […]

(b) necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health;

One effect of providing for host State justifications within a substantive provision could relate to the burden of proof. If these exceptions are interpreted in a manner such as the trade case law concerning Article 2.4 of the TBT Agreement, Articles 3.3 and 5.7 of the SPS Agreement, or Article 1102 of NAFTA,Footnote 126 this would mean that the burden of proof remains with the claimant (the investor in this case). That approach is far from clear, however, as the text closely mirrors ‘GATT Article XX’ style exceptions; a tribunal could view the burden of proof as shifting towards the respondent (the State) once a prima facie case has been established. Under GATT Article XX, WTO Members have at times found it rather difficult to successfully discharge this evidentiary burden.Footnote 127

As a result, embedding a public health exception within a substantive provision might make it easier for a State to justify that measure, insofar as a claimant would have to prove that a measure was not, for example, necessary to protect human health.Footnote 128 However, this alternative could require inserting references to public health in each and every substantive provision (which none of the new generation treaties does), since an exception in one particular substantive standard only applies to that standard. Reflecting upon the inherent tension between, on the one hand, the ‘intuitive appeal’ in requiring a State to justify its regulatory action (given it is best placed to provide evidence relating to the ‘nature, purposes and expected or actual effects of its action’) and, on the other, the respect for sovereign regulatory freedom reflected in general international law, States may have to make a ‘conscious decision’ as to who bears the burden of proof and clearly articulate that decision in the treaty text.Footnote 129

If treaty negotiators are of the opinion that exceptions should only apply to a select few articles, specific carve-outs may be more appropriate, like in the articles on national treatment and taxation in the EU–Singapore IPA.Footnote 130 Such a calibrated approach has become typical in (indirect) expropriation provisions. For example, Annex 9-B of the CPTPP states:

Non-discriminatory regulatory actions by a Party that are designed and applied to protect legitimate public welfare objectives, such as public health,Footnote 37 safety and the environment, do not constitute indirect expropriations, except in rare circumstances.

However, general exceptions or carve-outs for public health may be more appropriate where drafters intend such provisions to apply to several articles and they do not see a need for a differentiated or calibrated approach in each particular article.

E. GATT/GATS References and the Nexus requirement: ‘Necessary to’

Whether they opt for a public health exception in a general exceptions article or in individual substantive articles, treaty drafters may have to decide whether to explicitly incorporate GATT Article XX (or GATS Article XIV), whether to draft a public health exception that is closely or lightly modelled on GATT/GATS without any express reference, or whether to devise a new formulation altogether. As seen above, the parties to CETA have opted for explicit incorporation,Footnote 131 while the EU–Singapore IPA uses the same wording (‘necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health’)Footnote 132 but without any reference to GATT or GATS. As of yet, no treaty drafters have developed a completely new formulation.

Whether an explicit reference to GATT/GATS is included or not, the effect would seem to be the same. Perhaps, where such a reference is made, it could be easier to rely on GATT/GATS jurisprudence to interpret the required nexus between the measure at issue and the public health objective it is aimed to achieve. Most treaty drafters seem to have chosen to create a public health exception only for measures ‘necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health’.Footnote 133 This requires looking more closely at provisions that do include the ‘necessary to’ nexus requirement and then to assess its consequences in more depth.

Confusingly, many treaty drafters have adopted a mixed approach, referring to public health in various articles, some of which require necessity, while others do not. Article 8.9(1) of CETA, for example, sets out that ‘the Parties reaffirm their right to regulate within their territories to achieve legitimate policy objectives, such as the protection of public health’, which could be construed as requiring that a respondent State must merely intend to achieve a public health goal in order to exempt the measure from scrutiny.

However, the purpose of reaffirming the right to regulate in this Article allegedly:

… lies within the provision's interaction with the other provisions of the CETA Investment Chapter, mostly with the investment protection standards. In this respect, Article 8.9(1) CETA does not operate as a general exception clause excluding a Contracting Party's liability based on the CETA investment protection standards. Article 8.9(1) CETA rather serves interpretative purposes and adjudicators have to take the provision into account when an investment protection standard clashes with a host State's regulatory measure. CETA makes the inherent right to regulate of the contracting Parties the starting point of legal analysis. [Footnotes omitted; emphases added.]Footnote 134

The term ‘exception’ is therefore unhelpful, at least in this context. What matters is that a respondent State cannot escape its obligations under CETA simply by invoking Article 8.9(1). Otherwise, the assertion of the ‘right to regulate to achieve legitimate policy objectives’ would suffice to dismiss any claim. The list in Article 8.9(1) is notably indicative (‘such as’), so that any legitimate policy objective would suffice—but all State measures (are meant to) serve some legitimate policy objective, whether directly or not. Additionally, if Article 8.9(1) were a trump card, then paras 2–4 (‘for greater certainty…’) would seem redundant.

CETA's general exceptions article does require necessity to be established: ‘nothing in this Agreement shall be construed to prevent the adoption or enforcement by a Party of measures necessary […] to protect human, animal or plant life or health’.Footnote 135 Potentially, the reason why necessity is required here is that this is an exception whereas the right to regulate is not. Moreover, the discrepancy could be justified because Article 28.3.2(b) (General Exceptions) only applies to Chapter 8, Sections B and C (Market access and performance requirements, and non-discriminatory treatment, ie national treatment, most-favoured-nation treatment and treatment of senior management and boards of directors), whereas Article 8.9(1) applies to the entire Chapter. As this is not clear from the text, future jurisprudence should clarify this issue.

Another example of a BIT employing necessity as a nexus requirement for public health objections is the Dutch Model BIT (2018). It refers to necessity in its Preamble (‘measures necessary to achieve legitimate policy objectives, such as the protection of public health’) and the article on the right to regulate (‘the right of the Contracting Parties to regulate within their territories necessary to achieve legitimate policy objectives such as the protection of public health’) but not in the article on expropriation:

non-discriminatory measures of a Contracting Party that are designed and applied in good faith to protect legitimate public interests, such as the protection of public health, […] do not constitute indirect expropriations. [Emphasis added.]

The reason for the absence of a necessity reference could be that this provision is a codification of police powers rather than a duplication of GATT/GATS provision on general exceptions. This again depends on whether the application of the police powers doctrine includes a necessity assessment—if it does, perhaps necessity does not need to be spelt out, because it will always be brought in as a matter of interpretation. The customary doctrine of police powers should not be subjected to a necessity assessment, unless this is explicitly stipulated in a treaty as a matter of lex specialis. The police powers doctrine has been commonly interpreted in practice as being subject to a reasonableness or proportionality analysis.Footnote 136 The use of the formulation ‘designed and applied’ as seen in the Dutch model BIT (2018) can also be found in the expropriation standard in the CPTPP, CUSMA, the Indian Model BIT (2015) and the Ethiopia–Qatar BIT (2017).Footnote 137 The latter treaty also uses this phrase when carving out an exception for public health measures in its most-favoured-nation treatment standard.Footnote 138

As demonstrated by the WTO jurisprudence, a necessity requirement sets a high threshold for host States.Footnote 139 Indeed, in WTO disputes, respondents have far from always managed to justify a measure on this ground, so it can be predicted that, if the necessity test is applied in the same manner in investment disputes, host States might find it difficult to discharge the evidentiary burden of proof.Footnote 140 It is uncertain whether this was the intention of the treaty drafters—on the contrary, based on public statements,Footnote 141 the expressed intention would seem to have been that many, if not nearly all, public health measures would be justifiable on this basis. For this reason, the requirement that the measure be ‘necessary’ has been rightly criticised as overly onerous and showing insufficient deference to host State policies. For example, in his Separate Statement to the Award on the Merits in UPS v USA, Ronald Cass found that necessity testing would ‘greatly expand the power of NAFTA tribunals to evaluate the legitimacy of government objectives and efficacy of governmentally chosen means’.Footnote 142

In any event, under GATT Article XX, the ‘failure to establish that a challenged measure is justified by one of the general exceptions is typically due to discriminatory application of the measure contrary to the chapeau of the general exceptions’, rather than the necessity requirement, as the conditions of the chapeau have been construed in a strict manner by WTO panels and the Appellate Body.Footnote 143 WTO case law is deferential with respect to ‘necessity’ under GATT Article XX and while investment tribunals rely on such case law, they tend to construe necessity in a manner that restricts policy space more than the WTO Appellate Body does.Footnote 144 The appropriateness of importing the principle of proportionality, especially stricto sensu, has been contested by commentators on WTO law and investment arbitration.Footnote 145 However, the absence of a layer of general exceptions may create scope for investment treaty tribunals to impose a proportionality test in the application of substantive obligations. This would arguably be more intrusive than the general exceptions interpretation by the WTO Appellate Body (granting significant discretion to WTO members in choosing their preferred level of protection with respect to a given legitimate policy objective).Footnote 146 Other scholars have questioned whether a balancing test—effectively a question of personal judgement—accords adjudicators an undesirable degree of discretion.Footnote 147

Either way, ‘the stringency of the test required to prove that a measure is “necessary”, and what may constitute “arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination between investments or between investors”, are difficult questions that will determine the scope and utility of including these exceptions in IIAs’.Footnote 148 Perhaps a clearer approach is presented in the wording of Article 2.2 of the TBT Agreement, which provides that ‘technical regulations shall not be more trade-restrictive than necessary to fulfil a legitimate objective [inter alia, protection of human health], taking account of the risks non-fulfilment would create’. In applying this provision, the WTO Panel in Australia—Plain Packaging reaffirmed that it was not entitled to question the ‘underlying purpose of the challenged measure’, provided the objective was legitimate, but only ‘the degree to which an equivalent contribution could be achieved through other less trade-restrictive measures attaining the same objective through different means’.Footnote 149

F. Self-Judging Necessity Tests

To further confuse matters, some treaties contain self-judging necessity requirements. For example, the Indian Model BIT (2015) states: ‘[n]othing in this Treaty precludes the Host State from taking actions or measures of general applicability which it considers necessary’. Similarly, the CPTPP and CUSMA both stipulate:

Nothing in this Chapter shall be construed to prevent a Party from adopting, maintaining or enforcing any measure otherwise consistent with this Chapter that it considers appropriate to ensure that investment activity in its territory is undertaken in a manner sensitive to environmental, health or other regulatory objectives.Footnote 150 [Emphasis added.]

This should avoid the application of an overly restrictive necessity test, but it risks foreclosing any kind of judicial review, no matter how marginal, so that even manifestly ‘unnecessary’ or ‘inappropriate’ measures would come to fall under the public health exception on the mere say-so of a respondent State. As the recent panel report in Russia—Traffic in Transit suggests, while such provisions may allow a larger margin of discretion for the invoking State, the adjudicatory body nevertheless retains the power to determine on an objective basis whether the requirements articulated therein are met.Footnote 151 At the same time, investment tribunals have refused to read clauses as self-judging in the absence of clear indications to that effect, but have accepted that clear treaty language might indicate unbridled discretion on the part of invoking States.Footnote 152 Additionally, with regard to self-judging provisions in CPTPP and CUSMA, it is unclear how tribunals, even if allowed to exercise some form of review, would have to measure ‘appropriateness’, which is arguably a different—potentially laxer—standard than ‘necessity’.

Beyond express treaty texts, the notion of necessity under general international law has previously posed interpretative pitfalls for investment arbitrators. For example, several annulment applications were made (with varying results) on the basis that tribunals had allegedly manifestly erred by integrating the conditions for the customary plea of necessity as a circumstance precluding wrongfulnessFootnote 153 in their interpretation of a provision that exempted ‘essential security measures’ from the jurisdictional scope of the applicable treaty.Footnote 154 Without any further guidance in the treaties themselves, therefore, many questions remain as to how necessity should be interpreted under these new IIAs. For example, to what extent are such provisions a reference to customary international law? What form should Least Restrictive Means (LRM) tests take under these agreements?Footnote 155 Should there be a strict suitability test? What role (if any) should proportionality stricto sensu have?

It is unsurprising that some commentators are sceptical of the use of a proportionality analysis to ‘second-guess the level of protection that a state has chosen as against the interest it is protecting’.Footnote 156 If an impugned health measure were implemented in response to a public health emergency of international concern, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, an investment tribunal could for example refer to the proportionality test under the International Health Regulations as a relevant rule of international law in accordance with the principle of systemic integration.Footnote 157

Furthermore, in treaties which include necessity as a requirement with regard to some, but not all, public health carve-outs,Footnote 158 should a different test be applied depending on which article is invoked? This could create a situation in which a public interest measure prevails over investment protection with regard to the expropriation standard but not with regard to FET. Finally, it is unclear how tribunals are expected to deal with measures which may well be ‘designed and applied’ to protect public health but that are ineffectual and disproportionate at doing so, or vice versa: measures that were not specifically designed or applied with a public health purpose in mind, but that do contribute to such objectives in practice.

In sum, the new generation of IIAs mentions public health in a number of different contexts, ranging from the right to regulate to article-specific exceptions and general exceptions. However, the consequences of these inclusions remain unclear with respect to the earlier line of arbitral case law.

IV. NEW TREATIES, DIFFERENT OUTCOMES?

This section examines whether past cases would have been decided differently under the new generation of investment treaties. It also assesses whether existing concerns relating to public health and investment are alleviated through revised public health stipulations, and whether a new type of health-related investment dispute can be anticipated under these new treaties. Current circumstances demand sustained efforts by treaty negotiators to integrate foreign investment and public health in a balanced framework that safeguards reasonable regulatory measures without disincentivising private investment in health infrastructure. However, many of these insights could be transposed to provisions or disputes concerning other regulatory objectives.

A. Existing Deference towards States’ Regulatory Powers

The new generation of IIAs and FTAs with an investment chapter is not revolutionary, but rather makes explicit the regulatory power of States under general international law that had already been inferred by investment tribunals operating under the first generation of treaties, as in Philip Morris v Uruguay and Chemtura v Canada. For instance, investment tribunals have demonstrated how IIAs can be interpreted so as to accommodate States’ need to regulate environmental protection in the pursuit of public health goals. Relying on investment protection to circumvent public health measures by arguing that they violate intellectual property rights has not been a successful endeavour for investors either.Footnote 159 As a result, it would seem unlikely that any of the cases analysed above would have been differently decided under a ‘new generation’ treaty.

Nevertheless, from the perspectives of democratic legitimacy and coherent treaty interpretation, it is preferable that grounds which may well be (and have been in the past) determinative of the outcome of a case are explicitly provided for in the legal instrument that governs the case, ie the investment treaty. For this reason, revised treaty stipulations could alleviate existing concerns relating to public health and investment. Taking a lead from Philip Morris v Uruguay, investment treaties could explicitly affirm the discretion of host States to define public health goals and put in place measures to achieve them, as long as the relationship between means and ends is justifiable. States could also refer to specific health or environmental treaties as examples of international obligations that they might reasonably pursue without violating investment treaty standards.Footnote 160 Tribunals can in any case be expected to continue to display deference towards the exercise of a State's regulatory powers even under BITs that do not explicitly refer to public health, such as the Switzerland–Uruguay BIT (1991). Due to this general assumption of deference to the host State, the demarcation of what constitutes a public health measure must be carefully made.

B. Demarcation of Public Health Measures and Intellectual Property Rights

Most new treaties that refer to ‘public health’ do not define what exactly is meant by this term.Footnote 161 An exception in this regard is the CPTPP which stipulates that ‘regulatory actions to protect public health include, among others, such measures with respect to the regulation, pricing and supply of, and reimbursement for, pharmaceuticals (including biological products), diagnostics, vaccines, medical devices, gene therapies and technologies, health-related aids and appliances and blood and blood-related products’.Footnote 162 This is not an exhaustive list, so disputes might arise as to whether a particular measure qualifies as a public health measure under the applicable treaty. A concern could be that States might attempt to label any measure as a ‘public health measure’ in order to escape adjudicatory scrutiny, which has occurred in regard to taxation measures. For example, a recent open letter from over 1,200 US health experts deemed the ‘right to protest’ to be ‘vital to the national public health’.Footnote 163 Would this constitute a sufficiently scientific basis to argue that measures curtailing the right to protest could clash with ‘public health’—and the latter should prevail? While this issue is unlikely to come up under an IIA, it illustrates how broad this concept can be.

An alternative way to tackle this question is to investigate what should not be protected by a general exception for public health. Arguably, such a list would include one or more of the following categories: measures unrelated to health, discriminatory measures, indirect expropriatory measures, measures that egregiously breach legitimate expectations (eg Vattenfall II),Footnote 164 and measures that breach the principle of good faith, the rule of law, or constitute an abuse of due process.Footnote 165 Such an approach is not unheard of. For example, a list detailing what is not covered by a particular provision was included in the Indian Model BIT (2015), which stipulates that ‘non-discriminatory regulatory actions by a Party that are designed and applied to protect legitimate public welfare objectives such as public health, safety and the environment shall not constitute expropriation’.Footnote 166

There are further, more controversial, categories that could be considered as pushing a measure outside the scope of protected public health measures, such as health-related measures which have no or little scientific basis. The Single Presentation Requirement (SPR) in Philip Morris v Uruguay is a good example of this.Footnote 167 This requirement prevented manufacturers from marketing more than one variant of cigarette, which might suggest that one brand variant is less harmful than another.Footnote 168 The Tribunal noted that its role was not to determine whether this measure actually had the intended effect of reducing cigarette consumption (a question on which the existing evidence was discordant); rather, what mattered was ‘whether it was a “reasonable” measure when it was adopted’.Footnote 169 For the majority, the Respondent State was justified in relying on available, albeit inconclusive, evidence rather than conducting additional studies.Footnote 170 The partially dissenting arbitrator started his analysis from the same standard on reasonableness but reached the opposite conclusion for want of firm evidence to support the utility of the measure.Footnote 171 The divergence between majority and minority in the application of a commonly known FET standard reflects the uncertainty about the precise content of certain investment obligations,Footnote 172 potentially leading to a rigidity in reasoning when evaluating regulatory measures with a disputed scientific basis.

In order to better determine what merits protection, States should also define which intellectual property rights they wish to protect under their IIAs.Footnote 173 Currently, it would seem to be assumed that all intellectual property rights are covered as soon as any reference to ‘licences’, ‘returns’ or even broadly ‘assets’ is included in the investment definition and therefore benefit from all procedural and substantive protection under the treaty.Footnote 174 States could alternatively opt to restrict not only which intellectual property rights they wish to protect, but even (if they wish to maintain the current wide coverage) set additional requirements that need to be met before an investor can successfully invoke the IIA. This could, for example, put an end to the practice of registering a patent in a certain jurisdiction for the mere purpose of preventing manufacturing and export, while the investor never manufactures or distributes that drug in the registered territory.Footnote 175

C. An Alternative Nexus Requirement: ‘Related to’

As outlined above, the requirement that a measure be ‘necessary to’ achieve a public health objective may in effect exclude many public health measures from the scope of protection. An alternative would be to use the formulation ‘related to’, as found in GATT Article XX(g) which is more flexible than the necessity requirement,Footnote 176 although this could potentially protect an overly broad and vague array of measures. For example, mental health measures fall under the umbrella of being ‘related to’ public health, so the question could be whether a permit turning a piece of land into a public park is justifiable on the ground that it might improve the mental health of the neighbourhood's inhabitants? All manner of regulatory areas from anti-discrimination to culture, energy, the environment, finance, intellectual property, food labelling, labour rights, transport etc could be described as ‘relating to public health’. Arguably, exceptions with nexus requirements of a mere relationship, such as that of GATT Article XX(g), ‘hardly impose[…]’ more discipline than the language of carve-outs and reservations’.Footnote 177 Yet the WTO Appellate Body has nevertheless found that, under Article XX(g), a ‘substantial relationship’ must exist between the measure and the conservation effort, so this requirement of a relationship is hardly perfunctory.Footnote 178

Changing the current approach from providing an exception for public health measures that are ‘necessary to’ achieve a certain objective to one that also protects those that are merely ‘related to’ public health could, for example, change the outcome in cases such as Achmea v Slovakia, where a sudden reversal of government policy regulating the health insurance market was considered a violation of the investor's rights. Leaving the compatibility with EU law aside,Footnote 179 would any regulation of the health insurance market automatically be immune to claims because of its relationship to health? While such a policy reversal may not be ‘necessary’, or even counter-productive to achieve certain public health objectives, it would certainly be ‘related to’ health.

Of course, an appropriate balance would need to be found through treaty interpretation: while the use of ‘necessary to’ might exclude too many genuine public health measures from the scope of protection against investment claims, a change to protect all measures that are ‘related to’ public health might tilt the scales overly much in the opposite direction and take away protection from bona fide investments.Footnote 180 For treaties that contain a necessity requirement, such a balance could be found by interpreting necessity not as demanding that the public health measure be the only possible measure to achieve a certain objective, but in light of its context, the best way (or at least ‘a reasonable’ way in light of all circumstances) of achieving it. This could be, for example, because other measures are overly onerous, expensive or less efficient. For treaties that contain no nexus requirement or that merely demand that the measure be ‘related to’ public health, a proportionality test could be applied (even in the absence of an explicit reference in the treaty).

Arguably, a similar concept of a balancing exercise lies behind the provision included in the Norwegian Model BIT (2015), discussed above (section III.1). According to that provision, measures taken in pursuance of the protection of public health (among other objectives) are not inconsistent with obligations under investment law, as long as they bear ‘a reasonable relationship to rational policies not motivated by preference of domestic over foreign owned investment’.Footnote 181 However, where a measure is related to a genuine public health requirement, but is far more restrictive or creates far more damage than reasonably required to achieve the stated goal, the measure could fall outside of the public health exception.