INTRODUCTION

Although traditionally more archaeological work has taken place on rural monastic sites, the rise of rescue and subsequently developer-funded archaeology has led to more investigations on the primarily urban friaries. While much of this work is small-scale and relatively uninformative, major excavations of Augustinian friaries in England include Canterbury,Footnote 1 Kingston-upon Hull,Footnote 2 Leicester,Footnote 3 WarringtonFootnote 4 and Winchester.Footnote 5 There are also some surviving standing buildings, notably at Clare.Footnote 6

By the mid-thirteenth century, Cambridge (fig 1) was a long-established, medium sized market town and inland port, focused on the corn trade. It had also become a notable centre of learning, with the university founded c 1208–10 and evidence of academic activities from the 1220s onwards.Footnote 7 This made Cambridge particularly attractive to the growing mendicant orders, which sought to bring the religious ideals of the monastic life into urban settings and had an ardent desire to be involved in academic theology.

Fig 1. Location map showing the East Anglian friaries of the Cambridge Austin friars administrative limit and reconstruction of Cambridge c 1350, showing friaries and the 140 cannes limit in existence when the Cambridge Austin friars was established. Image: based on an original graphic produced by Vicki Herring for the After the Plague project.

The defining characteristics of the medieval mendicant movement were a commitment to poverty and begging, the mobility of its members combined with the international nature of the order and the urban locations of most friaries.Footnote 8 Although the four principal mendicant orders (Franciscans, Dominicans, Carmelites and Augustinians) differed in certain respects, this should not obscure their fundamental similarities. The Augustinians were distinct from the more prominent Franciscans and Dominicans in terms of their hermetic origins, lack of a motherhouse and being a rather more disparate and less uniform organisation. On theological issues they can broadly be characterised as more moderate; for example, unlike the Franciscans, they did not support the concept of absolute poverty.

In 1279/80 the Hundred Rolls for Cambridge, including outlying settlements, listed 806 urban properties;Footnote 9 712 of these properties would have had occupants, with a population of c 3,500.Footnote 10 The Hundred Rolls list various religious institutions, including the Friars Preacher (Dominicans), Friars Minor (Franciscans), Friars of the Sack, Carmelite Friars and Crutched Friars.Footnote 11 Not listed are the Hermit Friars of St Augustine (Ordo Eremitorum Sancti Augustini), commonly referred to as the Augustinian or Austin friars. Although the Augustinian order was created by the Great Union of 1256, some groups that formed this were present in Britain as early as 1249.Footnote 12 The Augustinian order was nearly suppressed in 1274, after the proposed simplification of religious orders at the Second Council of Lyon, but subsequently expanded in the 1280s thanks to papal support. In 1289 Edward i was passing through Cambridgeshire at Ely (5 October) and Fen Ditton (7 October). As he often did, Edward gifted local friaries a pittance of 4d per day, to feed the friars there. Edward gave the friaries in nearby Cambridge money for three days, with 240d for the Austin friars equating to twenty friars.Footnote 13 This is the earliest evidence for the friary, which was probably well established by 1289, given the number of friars,Footnote 14 but was still one of the smaller Cambridge friaries.

In 1297 there were thirty-six friars, while by 1326/8 their number had risen to seventy.Footnote 15 Chapters of the Augustinian friars national province were held at the Cambridge friary in 1316, 1322 and 1323, and in 1318 the Pope declared it a studium generale, or international study house,Footnote 16 indicating that it was a well-established and respected centre of advanced learning. By the fourteenth century the Cambridge friary was the head of an administrative limit, broadly corresponding to East Anglia. This included friaries founded before Cambridge at Clare (1248/9), Huntingdon (1258), Gorleston/Little Yarmouth (1267) and Norwich (1277–89), and after it at King’s Lynn (by 1296), Orford (1295–9) and Thetford (1387–9).Footnote 17 Of the four orders of friars that survived after the early fourteenth century, the Austin friars in Cambridge was numerically less important than its Franciscans and Dominican counterparts and broadly equal to the Carmelites.Footnote 18 Although undoubtedly adversely impacted by the Black Death and other events in the fourteenth century, the Cambridge Austin friars remained important throughout its existence, with evidence for friars from Continental Europe studying and teaching there.Footnote 19 The friary was closely integrated into both the town, with evidence from several late fifteenth–early sixteenth-century wills and other textual sources, and the university, where the friars mainly studied theology, and the friary church was occasionally used for university events.Footnote 20 There was still a vibrant intellectual community in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, with evidence for traditional activities such as indulgences (1494) and a Scala Coeli altar (1517–18).Footnote 21 Slightly later, several individuals associated with the friary, including Robert Barnes (active at Cambridge c 1505–14 and 1521/2–6 and prior c 1523–5) and Miles Coverdale (active at Cambridge c 1520–8), were important Reformers.Footnote 22 When the friary was dissolved in 1538 there were only the master and three friars, although five other Cambridge Austin friars obtained licences to serve as secular priests in 1536 and 1538, indicating that there were at least nine members of the order present in the 1530s and possibly more.Footnote 23

THE SITE

The site occupied by the Cambridge Augustinian friary (figs 1–2) is bounded by Bene’t Street and Wheeler Street to the north (medieval Vicus St Benedicti), Free School Lane to the west (medieval Lorteburnestrata), Corn Exchange Street to the east (medieval le Feireyerdlane) and either the King’s Ditch or Pembroke Street to the south (medieval Langritheslane or Deudeneris lane). In 1908–9 building works revealed structural and human remains associated with the Cambridge Austin friars.Footnote 24 These were recorded by Edward Schneider (1863–1925), Clerk of Works (Architectural) for the university, and attracted the attention of the anatomist Wynfrid Duckworth (1870–1956) and various members of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society.

Fig 2. Plan of archaeological investigations in the street block occupied by the Cambridge Austin friars. Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit.

Subsequently there was only small-scale archaeological work at The Cavendish Laboratory,Footnote 25 until just over a century later the university decided to comprehensively redevelop the New Museums site. Following some minor investigations,Footnote 26 the Cambridge Archaeological Unit (CAU) undertook excavations in 2016–19, immediately adjacent to the remains uncovered in 1908–9.Footnote 27 This revealed intensive occupation prior to the establishment of the friary spanning several centuries, three phases relating to the friary and reuse of elements of the friary after the Dissolution until the early twentieth century. This earlier and later activity is considered in the supplementary material, which also includes detailed descriptions of the architectural fragments. The three phases associated with the friary comprise an early phase represented primarily by a cemetery, the subsequent construction of the friary cloister and the later addition of more structures, possibly including a second cloister. The human remains associated with the friary form the subject of a separate paper.Footnote 28

THE EARLY FRIARY, c 1280s–1330/50

In 1268 a papal order stipulated that new friaries had to be at least 140 cannae (c 245m) from existing friaries.Footnote 29 This meant that a considerable part of Cambridge was effectively off limits to the Augustinians in the 1280s (see fig 1). While this order was not always followed, it was in the case of the Cambridge Augustinian friary, potentially because the order was still relatively recent when the friary was founded in the 1280s. As already mentioned, the earliest textual evidence for the friary is the pittance of October 1289, when there appear to have been twenty friars. The founder of the friary was Geoffrey de Picheford, who created the house ‘for the souls of Edward i and his [de Picheford’s] son Anulph’ and ‘for the increase of divine worship’ in the town.Footnote 30

De Picheford’s foundation bequest of a messuage with appurtenances (Plot 1A: fig 3) was given royal confirmation in June 1290 (for plot details, see supplementary material, table 1). No details are recorded, but it probably included the site the friary church was built on. In November 1290 the friary agreed to pay 4s per annum to Barnwell Priory, who held the advowson of St Edward’s parish, as compensation for lost revenue. This lost revenue would typically be from tithes and burial fees, implying that the friary had a functioning church and cemetery, although the friars’ servants still had to attend the parish church.Footnote 31 Another land parcel by the King’s Ditch was acquired in 1291 (Plot 2), this was described as abutting northwards onto ‘the friars’ wall’, suggesting that the foundation bequest had included a large close, stretching southwards from Bene’t St/Wheeler St nearly to the King’s Ditch (Plot 1B). Then in 1293 a grant of a 140ft × 24ft parcel of land on Free School Lane ‘for the enlargement of the precinct’ by John Bernard (Plot 3) was confirmed. These three plots form the core of the early friary.

Fig 3. Reconstruction of the early/mid-thirteenth-century street block later occupied by the Cambridge Austin friars. Limitations in the evidence make certainty impossible, and other layouts are possible: 1) plots in the street block; 2) parishes; 3) sequence in which the friary acquired properties. Images: Cambridge Archaeological Unit, based upon information from Rosemary Horrox and Nick Holder.

In 1302 the friary was granted rights of burial, preaching and hearing confessions for those who were not members of the order.Footnote 32 Further messuages from Geoffrey of Syteadun of Waleden and William de Novacurt fronting onto Free School Lane (Plot 4), and Bene’t St/Wheeler St (Plot 5) were confirmed in March 1305. The acquisition of Plot 5 was particularly significant, as this probably formed part of the site of the friary church (see fig 3.1). In 1308 another messuage on Free School Lane from John son of William of Cambridge was confirmed (Plot 6). Later documents of 1324–9 and 1335–43 indicate that Plot 4 was split, with part being incorporated into the friars’ precinct and part (presumably on Free School Lane) made into a dwelling.

There was then apparently a considerable hiatus in the acquisition of additional plots, so these six areas formed the basis of the first phase of the friary. In October 1319 the rent the friars paid to the Crown on the de Picheford property was cancelled, with the grant also mentioning ‘improvement of the decorations of their church’.Footnote 33 This was repeated in 1324, suggesting that the friars were completing work on their church at this time.Footnote 34

Excavations in 2016–17 revealed substantial wall footings of a major building (Building 1) (fig 4) and a cemetery to the south of it. The identified elements of Building 1 are projecting features, such as buttresses, from a large building located to the north that is probably the friary church. These features were 1.04–1.54m wide, at least 1.0–1.6m deep and filled with firmly compacted bands of gravel. This form of footings was common to all those investigated at the friary, regardless of date. While paralleled at other broadly contemporary institutional buildings in Cambridge, this type of footing was by no means universal. The cemetery comprised thirty-two west–east aligned extended supine inhumations in simple earth cut graves, with the head to the west. The age and sex profile of these individuals, plus the presence of numerous buckles indicating clothed burial and distinct arm/hand positions, suggest that these were predominantly, but not exclusively, friars.Footnote 35 Additional heavily truncated wall foundations investigated in 2018–19 represent another structure (Building 9). A doorway recorded in 1908–9 can be stylistically dated to c 1280–1300 (doorway A in 1908–9, now AF50: fig 5). Ultimately located in the southern claustral range, at the eastern end of the southern wall, it appears that the doorway was reused in this location.

Fig 4. Plan of the Cambridge Austin friars c 1279/89–1380/1420. Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit.

Fig 5. Clunch portal stylistically c 1280–1300 in the southern claustral range (AF50): 1) detail of jamb moulding, showing apparent use of square with 2ft (c 0.6m) diagonal to regulate positions of two orders; 2) extant and conjectured masonry; 3) restored sectional elevation and plan showing operation of door leaf (exterior to left); 4) how the proportions of the portal were set out using a circle with a radius of 5ft (c 1.5m). Images: Cambridge Archaeological Unit, based on original graphics by Mark Samuel.

Several reused architectural fragments are dated stylistically to c 1220–80 (AF2, AF10, AF4) and c 1260–80 (AF19, AF40, AF45). Some of these may derive from earlier buildings, but it is likely that some if not all of them relate to the earliest friary buildings and were stylistically rather old fashioned. There were also some fragments stylistically dated to after c 1280 assigned to this phase (AF21, AF34, AF37).

Several stylistically thirteenth−fourteenth-century fragments of window glass with brown/black enamelled grisaille decoration from small geometrically shaped quarries of leaded windows were recovered (fig 6). Many represent parts of floral border designs. While some may relate to later phases of the friary, a few pieces were recovered from contexts indicating that they date to the late thirteenth−early fourteenth century. Similarly, there is evidence for the use of ceramic roof tiles produced on the Isle of Ely in late thirteenth−early fourteenth-century friary buildings. This includes peg tiles and a group of crested ridge tiles with dark green glaze and a variety of crest styles (fig 7). Fragments of these were recovered from mid-fourteenth−early fifteenth-century features and would have been a visually prominent architectural feature, although it is unclear if the crests were used on a single roof or if different roofs had distinct types of crests.

Fig 6. Decorated window glass that stylistically appears to derive from thirteenth–fourteenth-century buildings at the Cambridge Austin friars: 1) quarry fragment in green glass with a leaf, possibly ivy, painted in brown enamel, where the enamel is used to paint the veins of the leaf and to fill the background leaving the leaf in green glass, thirteenth–fourteenth century <317> [3354] F.669; 2) quarry fragment in amber glass with brown enamel used to paint the outline and veins of a hawthorn leaf. Probably formed part of a decorative floral grisaille, fourteenth century <141> [3145] F.570; 3) complete pale green ‘white’ square pane, possible border piece, with painted fleur de lys design in brown paint from 1908–9 investigations, fourteenth century Z41520.117; 4) green ‘white’ incomplete square pane with flower/foliage design in brown paint, from 1908–9 investigations, fourteenth century Z41520.86. Images: Cambridge Archaeological Unit, images of glass discovered in 1908–9 courtesy of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge.

Fig 7. Group of crested ridge tiles with dark green glaze in fabric TZ42.1; depositional context indicates that they come from an early building at the Cambridge Austin friars. Images: Cambridge Archaeological Unit.

As the cloisters were constructed c 1330/50–1400/20 (see below), this raises the question of where the friars met, ate and slept in the late thirteenth−early fourteenth century. The most likely answer is that, at least initially, they occupied existing buildings that they had acquired on Bene’t St/Wheeler St and Free School Lane. It is also possible that they constructed other buildings within the friary precinct outside the areas investigated so far.

REBUILDING THE FRIARY, c 1330/50–1400/20

In the 1330s the friary acquired more properties (see fig 3). In 1335 a messuage of Robert de Cumberton fronting on Bene’t St/Wheeler St (Plot 7) and another of Thurstan le Bedell on Free School Lane (Plot 8) were acquired. A messuage of John de Brunne on Free School Lane (Plot 9) followed in 1337 and one of John de Paunton and his wife Margaret (Plot 10) in 1338 followed. The borough treasurer’s account for 1346–7 records 71s received from the shops next to the wall of the Austin friars.Footnote 36 In July 1349, in the aftermath of the Black Death, the friars acquired a large messuage and toft granted by Daniel de Felstede and John Ockles, presumably on Corn Exchange Street (Plot 11). By this time, the friary owned most of the street block, although at least two messuages on Free School Lane remained in private hands and the friars still owed annual quitrents to the Hospital of St John. The status of the area between the King’s Ditch and Pembroke Street is uncertain, while the friary may have owned it there is no conclusive evidence.

In 1356 protection was given to the friars’ servants, employed with a cart and three horses in the counties of Cambridge and Huntingdon, fetching victuals, stone and timber for the repair of their church.Footnote 37 Although the church lay largely outside the investigated areas, fragments of several windows probably relate to this (see below). This was followed by a major and prolonged claustral construction phase (figs 8–11). The architectural fragments and aspects of the 1908–9 records could indicate that the main cloister wall, outside the cloister walk, was built at once; this is incompatible with the more solid stratigraphic evidence that prevails. There are clear indications that the cloister was built in several stages: Building 2 was constructed before Building 3, while Building 4 was initially constructed as a free-standing structure before Buildings 3 and 5. Typological dating of architectural fragments from the cloister arcade indicates that it was constructed after c 1330 and would typically be stylistically dated to c 1330–50, although a date as late as c 1390 is feasible (see below). This dates Stage 1 to c 1330–50. The footings of Building 2 (Stage 3) truncate the skeleton of an individual who died of plague no earlier than 1349;Footnote 38 as there is evidence that the footings post-date this burial by some time, Building 2 cannot have been constructed prior to c 1360 and more probably c 1370. Building 3 (Stage 4) was constructed over the earlier cemetery. Bayesian modelling of three radiocarbon determinations from a stratigraphic sequence of skeletons indicates that there is only a 3.0 per cent likelihood that the cemetery went out of use by 1390 and that it probably went out of use c 1400–40.Footnote 39 Other evidence suggests that this is likely to have taken place in the earlier part of this date range, c 1400–20. While the overall claustral construction sequence contains speculative elements, it is likely that it was built in four stages as a long-term building campaign that took place over a period of decades spanning around fifty to ninety years (fig 10). The most likely sequence with tentative dates is:

-

Stage 1: western range plus Building 4 of the eastern range c 1330–50.

-

Stage 2: southern range including Building 5 c 1350–70.

-

Stage 3: eastern range with Building 2 c 1370–1400.

-

Stage 4: completion of eastern range with Building 3 c 1400–20.

Fig 8. Reconstructed plan of the Cambridge Austin friars precinct c 1380/1420–1538, the identification of some of the building functions is speculative and based on parallels from other sites. Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit.

Fig 9. Plan of the claustral area of the Cambridge Austin friars c 1380/1420–1538. Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit.

Fig 10. Plan of the claustral area of the Cambridge Austin friars c 1380/1420–1538, indicating the likely sequence of construction. Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit.

Fig 11. General view of Cambridge Austin friars c 1380/1420–1538, facing southeast. Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit.

Excavated buildings

In most places only below ground foundations of the cloisters survive. These typically consisted of carefully dug, vertically sided, flat-bottomed trenches 0.45m to 1.2m wide by 1.0m to 1.4m deep. The trenches were dug below the general disturbance from earlier features to a depth of c 0.1m to 0.2m into the natural gravels. Where even deeper earlier features with soft fills were encountered, these were carefully re-excavated and the foundation trench dug to the level of natural gravels. The foundations were excavated in short, c 10m lengths and then filled with compacted material prior to the next section being dug. This was presumably due to the instability of such deep vertically sided trenches, and there was little evidence of collapse or weathering of their sides. The trenches were backfilled with repeated thin c 50mm thick layers containing gravel, mortar and clay in varying proportions, which were carefully compacted before the next layer was added. At a depth of c 0.1m to 0.2m beneath the contemporary ground/floor level, layers of roughly shaped blocks of mortared Clunch (a local hard chalk, also known as Totternhoe stone or Burwell Rock) were laid. In selected locations, such as corners and buttresses, stronger Lincolnshire limestone, possibly Ketton rag, was employed. At this stage, the next length of trench was started. In general, these cut slightly into the backfill of the previous stage, with at least three such junctions identified.

Building 4 was the best-preserved part of the eastern claustral range and can be confidently identified as the chapter house (fig 12). The buttresses of Building 4, which project into Buildings 3 and 5, indicate that it was initially constructed as a free-standing building. The western wall and the doorway giving access to the cloister walk were recorded in 1908–9 and it is likely that there would have been a pair of flanking windows. Building 4 was c 6.7m wide and 11.5m+ long and is likely to have originally been c 13–15m long internally. No floors survive, but there were makeup/bedding layers and evidence of a tiled surface. Fragments from later deposits indicate that plain unglazed and red and yellow glazed tiles were used, perhaps in a chequerboard pattern. Along the southern side of the building there were c 0.6m wide mortared stone foundations for a bench. There was probably a similar bench along the northern wall, which had been removed by twentieth-century disturbance. Assuming that there were benches along both sides, and allowing a width of c 0.5m per individual, this gives a rough capacity for sixty to eighty individuals to attend chapter sitting on the benches, broadly comparable to the seventy friars documented in 1328. Six individuals were buried within the chapter house, a further grave-shaped cut almost certainly represents a seventh burial that was subsequently dug up and ‘translated’ elsewhere.Footnote 40

Fig 12. View, facing east-northeast, and plan of Cambridge Austin friars chapter house c 1330/50–1538, with detail of elevation and plan of doorway produced by Schneider in 1908–9. Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit, detail from Duckworth and Pocock Reference Duckworth and Pocock1910 (fold out illustration facing p. 39).

The corner of the eastern and southern claustral ranges was a square structure Building 5, with an internal area of c 7.8m by c 7.2m, which may have served as a warming room or more probably a kitchen, which are often square and located at the angle of the refectory, although if so it was probably too small to serve the entire friary and must have been for some specific group. This was entered from the cloister by a doorway at the southern end of the building, defined by an ‘old step 3ft.6in.’ (c 1.07m) wide and ‘very much worn in the centre’ recorded in 1908–9.Footnote 41 There may also have been a second doorway on the eastern side of the building at its northern end leading to an external open area, as the robbing of stonework from a door is the most likely explanation for a post-Dissolution pit. Within Building 5 were a substantial stone base and well. The base was constructed from mortared Clunch with some Lincolnshire limestone and was 1.2m (4ft) square and over 1.4m deep. One possibility is that this was for a hearth with timber flue over. The stone well was a substantial and well-built structure made from mortared Clunch with some Lincolnshire limestone, 1.5m × 1.4m in extent with an internal square mortar faced shaft 0.8m × 0.8m in extent. The well was 3.2−3.5m deep below floor level. The presence of a well within a building appears to be unusual in a monastic context, its function is uncertain. It would have supplied water for the kitchen, if this interpretation is correct, and could also have provided water for a communal washing area, or lavatorium, for use prior to entering the refectory. There is no evidence that the friary ever had a piped water supply and no other wells are known from the site, although they may well have existed.

The earlier structure Building 1 (see above), interpreted as part of the church, was modified and extended, creating Building 2. This was a substantial square or rectangular structure, with internal dimensions of 4.8m × 4.3m+ and large buttresses. Building 2 was presumably some form of structure projecting from the southern body of the friary church. Possibilities include a vestry, transept, porch, tower or chantry chapel. Building 2 has a buttress that projects into Building 3 of the eastern range, indicating that Building 2 was constructed earlier. After Building 3 was constructed, the function of Building 2 may have changed and it could have housed a set of stairs linking the church with the first floor of the claustral range, where a dormitory was probably located.

Building 3 was the latest element of the claustral range to be constructed. This had internal dimensions of 5.8m wide × 14.3m+ long. On its western side there was a wall with two large piers (2.0m × 2.0m in extent and c 1.4m below contemporary floor level), which would have functioned as reinforcements perhaps to heighten the wall to first floor level. A combination of these piers and the buttresses for Building 2 would have had a significant impact upon the internal space of Building 3, compromising its usefulness for many functions. One possibility is that Building 3 was the sacristy, where altar furnishings, vessels, candlesticks etc were stored, as the limitations of the space would not have been particularly problematic for this.

The first floor of the eastern claustral range over Buildings 3, 4 and 5 was probably occupied by a friars’ dormitory, potentially accessed by stairs in Building 2. A possible parallel is provided by the surviving buildings at the Coventry Carmelite friary, where the upper floor of the eastern claustral range was initially divided into an open dormitory and a study space with small individual study, which was later converted so the whole floor was a dormitory.Footnote 42 Beds in such a dormitory were probably c 0.9−1.0m wide, although perhaps taking up at least c 1.5m to allow access, by c 1.9m long. A c 30m long dormitory could therefore have held around forty friars, while this number could be doubled if there was a third floor. This could have provided all the communal accommodation required for the maximum documented population of seventy friars, especially as the prior would have had separate accommodation, and by 1348 masters of theology had separate cells.Footnote 43

The main part of the southern claustral range was recorded in 1908–9.Footnote 44 This shows a sequence of two doorways connecting the southern and western claustral ranges; doorway (E) was cut into by a late medieval door (D).Footnote 45 The southern range may well have been the friary refectory, but the limited nature of the records makes certainty impossible. The southern entrance survived in 1908 and was carefully moved and reassembled, although no record survives of this. This problematic feature can be closely dated by moulding (see below).

The foundations of the western claustral range were recorded in 1908–9, it had an internal width of around seven metres and a doorway leading into the cloisters. The western claustral range survived until at least 1780; this was originally known as the ‘Refectory’, although has also been identified as the infirmary.Footnote 46 A range of other functions are also possible, such as the library, and the archaeological investigations and depictions do not provide a clear answer. Although much altered, it was depicted in the eighteenth century as a large two-storied hall, originally of five bays with projecting buttresses. The upper storey had a row of traceried windows with equilateral arches, blocked and filled with smaller windows.

The cloister arcade

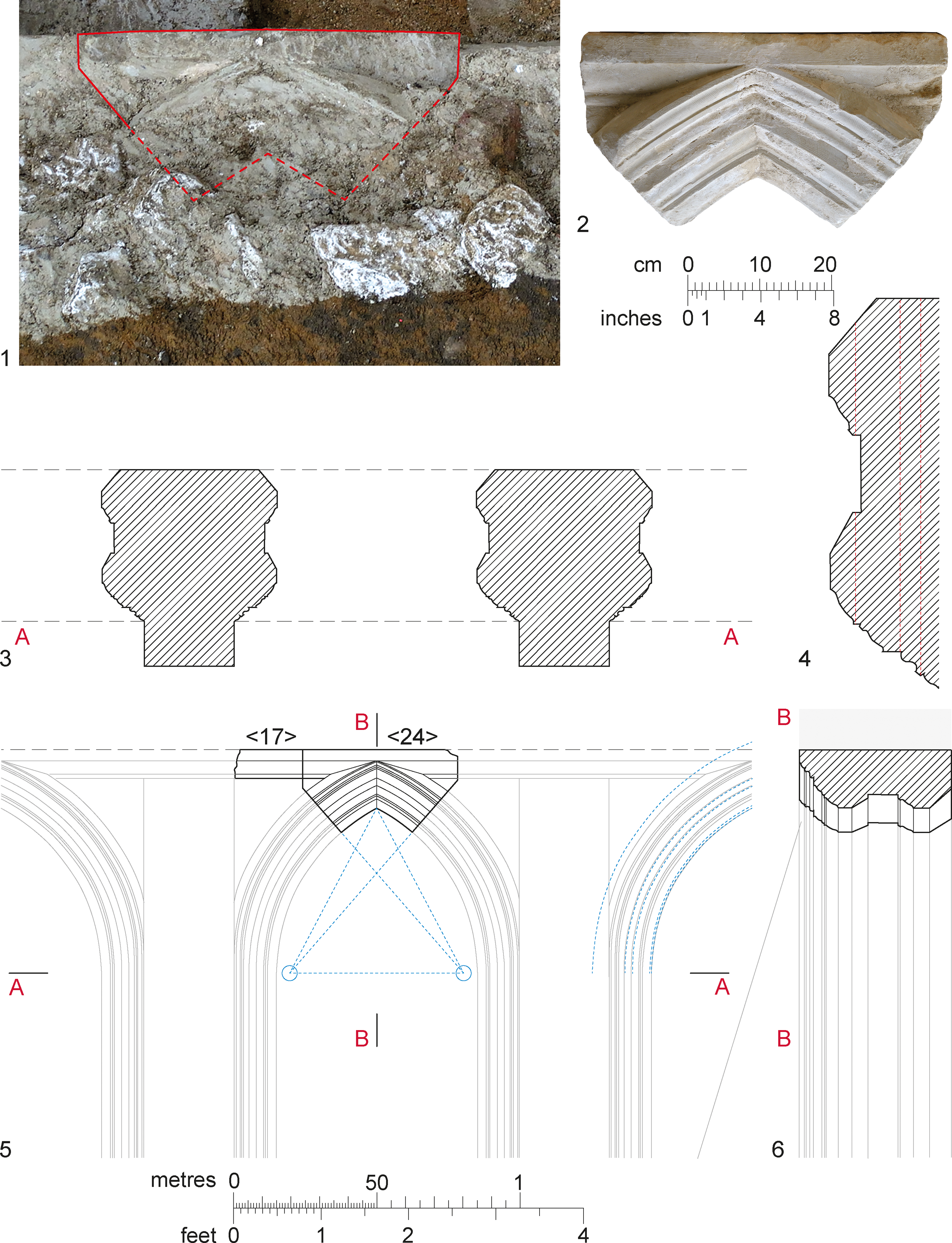

A cellar constructed after the Dissolution was faced with fifteen architectural fragments, largely from a cloister arcade (including AF17, AF22–24, AF27, AF32, AF36: fig 13).Footnote 47 These blocks had been reversed (fig 13.6) so that what had been the outer surfaces of the arcade were well preserved. The carefully maintained structure, from which the blocks originally derived, had been whitewashed on several occasions, protecting the mouldings throughout the existence of the cloister.

Fig 13. Clunch from apex and string of cloister arcade arches stylistically c 1330–90 from the Cambridge Austin friars (AFs22–24): 1) conjectured profile of arcade as springing line A–A; 2) detail of moulding at springing line (inscribed lined in blue); 3) detail of external elevation (geometry in blue); 4) sectional elevation of arch at B–B; 5) photograph of block; 6) view of block reused in later cellar, with block outlined in red. Images: Cambridge Archaeological Unit, based on original graphics by Mark Samuel.

The survival of three arch apices permits a partial reconstruction. The arcade’s stylistic context shows East Anglian traits. The arcade would appear to date to c 1330–50, although a date as late as c 1390 is feasible. The wave so freely employed in the arcade was employed intermittently until the Dissolution.Footnote 48 The ‘second variety’ is diagnostic of appearing after 1320 in East Anglia and the north-east Midlands, but was rare in the south east and no examples are recorded from the Midlands. It was normally employed on one side of an arch, appearing thus in the ambulatory arches at Tewkesbury (1320s).Footnote 49 Examples of the formation can be seen as far west as the ambulatory arches at Tewkesbury.Footnote 50 Locally it appears in the arcade (Arch A2) of the Church of St Mary & St Michael (previously St Nicholas), Trumpington, dated to 1330.Footnote 51 The rare ‘third variety’ of wave, with a single flanking fillet on the ‘chamfer plane’ of the wave,Footnote 52 is most common in the Midlands after 1330 and continues into the early Perpendicular.Footnote 53 One door and a single-light window may be part of the same building campaign. A door (reconstructed in plan below) was recorded during the 1900s.Footnote 54 It allowed passage from south to west ranges and was associated with the post-Dissolution barrel-vaulted passage that blocked the late thirteenth-century door immediately to the north. A stylistic similarity in the drop arch to the cloister arcade is clearly apparent.

Church windows

There is evidence for replacement of the friary church windows and some other architectural features c 1340–70 (AF11, AF26, AF28, AF31, AF33, AF43, AF47: figs 14–15). Several traceried windows are compatible to documented repairs to the church in 1356 (see above). Such re-fenestration seems to have been comprehensive. The mullion profile is ‘too common to be usefully considered’Footnote 55 and has no particular association with period (c 1320–1540), regions or monastic orders and is commonest in parish churches where finances were constrained. The tracery is more specific, displaying Flamboyant/early Perpendicular traits (c 1320–50). One key event may have been the acquisition of Plot 7 in 1335, as it appears that this formed part of the area occupied by the church (see fig 3). This indicates that the mid-fourteenth-century church was larger than its predecessor, which can only have extended as far west as Plot 5 acquired in 1305. The works to the church may have overlapped with Stages 1 and 2 of the construction of the cloister, although work on the cloisters could have been halted while those on the church took place.

Fig 14. Clunch jamb of a shuttered, probably single-light, window with a large iron staple set in lead, stylistically c 1320–70 (AF27). Original location in friary uncertain, potentially not from the cloister. The wall was probably 22in wide (c 56cm), while the window may have been 10in wide (c 25.2cm). Illegible graffiti on surface of stone. Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit, based on original graphic by Mark Samuel.

Fig 15. Clunch windows of stylistically c 1340–70; 1–2) plain chamfer mullion from large traceried window, probably from church AF31, showing detail of internal elevation (1) and rectified mullion moulding (2). Could relate to the phase of work on the church documented in 1356; 3–4) Clunch tracery detail showing ‘through’ reticulation of plain chamfer mullion from traceried window with detail of internal elevation (3) and inverted profile at springing line (4). The gap between window centres is probably 30in (c 76cm). Original location in friary uncertain, potentially not from the cloister; 5–7) plain chamfer tracery from two-light glazed window, paired trefoiled lights with quatrefoil in a two-centred head AF11 showing detail of external elevation of window, which is probably 22in wide (c 53cm), (5) inverted plan (6) and detailed plan of block (7). Original location in friary uncertain, potentially not from the cloister. Images: Cambridge Archaeological Unit, based on original graphics by Mark Samuel.

Only two window fragments are identical, but variations are otherwise slight with several windows probably represented. The date range is very narrow (see above). Typical late medieval masonry techniques are apparent. The dressings were cut on the bank using boaster chisels. The mason then employed different ‘grades’ of comb; coarse on joints, fine on exposed faces and superfine on cusps/foils. Axial lines and an ‘X’ (possibly a completion or joining mark) were often incised on the beds. These surfaces had been flattened with strokes of a coarsely serrated finishing tool before ‘combing’. Two dressings, a sill and a base mould, of this period are cut from Barnack rag, illustrating the intentional use of this resistant stone where most needed. Clunch is otherwise employed.

Other evidence

There was evidence that red ceramic peg tiles were commonly used on roofs, while glazed crested ridge tiles similar to those used during the earlier phase of the friary continued to be employed. There was also a large quantity of Collyweston stone roof tile, indicating a mixture of roofing types in use. Small quantities of brick were recovered, but its use appears to have been restricted. There were a range of floor tiles, all apparently produced on the Isle of Ely. The most common were plain mosaic tiles, 120mm square and 20mm thick. Most were unglazed (at least c 80 per cent of fragments), but there were some with yellow (thirty-three examples) and green (twenty-two examples) glaze. There were also some larger floor tiles, probably 150mm square and 30mm thick, including both unglazed and yellow glazed examples. A range of decorated floor tiles were also in use, although these were all recovered from post-Dissolution contexts, and it is unclear whether these relate to this phase or are later. There were glazed tiles depicting a six-spoked Catherine wheel, a central stripe with three flower motifs stamped along the stripe and an eagle, plus incised tiles including two examples with human figures and double border lines and one with four five-petalled flowers within outer rings containing five circles (fig 16).

Fig 16. Decorated floor tiles, probably all from the Cambridge Austin friars of c 1380/1420–1538: 1) incised tile recovered 1908–9 with four five-petalled flowers within outer rings containing five circles Z16298A.1-3; 2) glazed tile recovered 1908–9 depicting an eagle Z16298B; 3) line impressed tile with a central glazed stripe with three flower motifs stamped along the stripe, fourteenth–sixteenth century. Unstratified find from 2016–17 excavations <891> [1006]; 4–5) incised tiles recovered 1908–9 with parts of figures and two border lines Z16298 A.4–5; 6) glazed tile with a Catherine wheel, this would originally have had six spokes and the spikes on the spokes are clearly visible. From 2018–19 excavations <170> [3189] F.580. Images: Cambridge Archaeological Unit, images of tiles discovered in 1908–9 courtesy of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge.

Decorated window glass continued to be employed, although the recovery of the most significant pieces in both 1908–9 and 2016–19 from post-Dissolution contexts makes their attribution to specific phases of the friary problematic. Other glass recovered prior to construction of the Old Cavendish Laboratory in 1872 was reset in a panel in one of the side chapels of King’s College.Footnote 56 The evidence indicates the presence of high-quality window glass at the Cambridge Augustinian friary, this is also true of the Carmelite and Franciscan friaries in the town.Footnote 57 Most pieces are a mixture of green glass with enamelled grisaille decoration and more deeply coloured green, blue and red quarry fragments with no grisaille visible, which most likely represent a pale green/green grisaille window with coloured parts and border. There were two 135mm diameter fourteenth–fifteenth-century green glass roundels, with faint traces of paint. These have letters in Blackletter or Gothic script (c 1150–1590), probably commemorating benefactors. One is the letter W (𝔚), the other is less clear but is probably a B (𝔅) or G (𝔊) (fig 17.1–fig 17.2). There was a fourteenth-century, 75mm diameter, blue glass roundel with a flower and dot design in brown/black paint (fig 17.3), a fourteenth–fifteenth-century blue glass roundel or circular pane with flower design in black paint (fig 17.4) and fragments of at least three 80mm diameter fourteenth–fifteenth-century flashed ruby over very pale green ‘white’ roundels with scrollwork in dark brown/black paint (fig 17.5). Two particularly noteworthy fourteenth–fifteenth-century pieces are a colourless ‘white’ complete pane showing part of a foot painted with brown paint (fig 17.7) and a pale green ‘white’ almost complete pane showing a censer, a container in which incense is burnt during a religious ceremony, in brown paint and yellow stain (fig 17.8).

THE LATE FRIARY BUILDINGS, c 1400/20–1538

The cloister appears to have survived through the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries with no major changes, although repairs and modifications may have taken place. There is also no evidence for major works to the church. In the chapter house the bench foundations were widened to c 1.1m. To the south of the cloisters there was evidence for more buildings constructed in the fifteenth century. Building 6/10, which may be either a covered walkway or the eastern walk of a second cloister, comprised two 0.82m wide north–south aligned wall footings 2.0m apart and over 1.2m deep. The basal c 0.4m of the footings was filled with rammed bands of gravel, mortar and sandy silt. Above this there was an almost entirely robbed foundation of mortared stone blocks.

To the east of Building 6/10 is Building 11; the earliest feature potentially associated with this structure was a gravel surface, which may be an internal floor. Above this was a west–east aligned beamslot 0.40m wide, 0.29m deep and over 6.6m long that held substantial timbers, and an associated internal surface to the north. This appears to have been a substantial one- or two-storey timber building. In the early sixteenth century, Building 11 was completely rebuilt as Building 12. The building consisted of a mortared stone wall foundation 0.3m wide and up to 0.4m deep, with a c 1.8m wide gap, indicating the presence of a doorway. Associated with this was an internal rammed chalk floor. This floor became damaged through use, probably relatively rapidly, and was replaced by a much more robust floor made from pitched Collyweston stone tiles, which were laid both inside the building and in and outside the doorway. The nature of the floor indicates that this was not used for a high status function, where ceramic tiles would presumably have been used, but would have been expensive and might be appropriate for a stable or similar building. To the east of the doorway a mortared beamslot (F.615) was added at some point; this would only have held a relatively small 0.2m wide timber beam, suggesting that it relates to some form of minor lean-to structure.

Given the limited investigations and truncation, interpretation of these structures is problematic. The most parsimonious interpretation is that Building 6/10 is a roofed-in covered walkway and Building 11/12 an unrelated ancillary structure. A more extravagant possibility is that Buildings 6/10 and 11/12 represent part of the eastern range of a second inner cloister. The Regensburg or Ratisbon Constitutions of the 1290s, the fundamental body of rules for Augustinian friars, insist on the need for two cloisters so that different tasks could be kept apart, and with the second restricted to members of the order and subject to perpetual silence.Footnote 58 Excavation suggests that second cloisters were not unusual or confined to larger houses. In England and Wales, as well as the Augustinian friaries at Leicester and London, there were Dominican (Beverley, Bristol, London and Oxford) and Franciscan (Carmarthen, Dunwich, London and Walsingham) examples.Footnote 59 At the Clare Augustinian friary, rather than a full second cloister there was small court of timber framed buildings to the south of the main cloister, which included the infirmary, a dining room and latrine.Footnote 60 There was effectively a spatial hierarchy of privacy at friaries with a second cloister. The friary church was frequently open to the entire lay population, the first cloister was open to the secular clergy and select members of the laity on specific occasions, while the second cloister was closed to all but members of the Augustinian order. As such second cloisters housed functions where public access was not required and privacy might be viewed as advantageous. At the London Augustinian friary this included the kitchen, bakehouse, infirmary, dining room and library. Given the extent of the site that the Austin friars at Cambridge owned, its importance and the size of its population a second inner cloister is inherently likely; however, given the scale of investigations, this second inner cloister should be considered plausible, but speculative.

Only one architectural fragment, from a window stylistically dated to c 1370–1470 (AF46), appears to relate to the later friary. Although some details are uncertain, the sixteenth-century friary cloister can be reconstructed with some confidence (fig 18). Some of the decorated floor tiles and window glass already discussed may relate to this phase, with some of the glass stylistically likely to be early sixteenth century (fig 19.1). Fragments of fifteenth–sixteenth-century milled lead window without reeding within the channel were recovered from Pre-Dissolution contexts, indicating replacement or repair of windows. A fragment of finely moulded and painted plaster is ‘architectural’ in character and may be part of a cornice (fig 19.2). One part of the piece has whitewash, while some bands have been painted gold and the most detailed section has a red background with gold rosettes. The design appears Gothic in character, suggesting an early sixteenth century date. A small triangular shaped Clunch fragment with gold and red paint outlined in black is presumably a fragment of sculpture (fig 19.3).

In 1537 3¼ hundredweight of lead had been sold and in 1538 the friary was described as having little or no lead.Footnote 61 In 1544 the church steeple and gutters had a fother of lead, just less than a metric tonne. In total this suggests around thirty-five square yards of lead roofing, a small amount that implies that most roofs were of tile or slate. The 1544 survey also values other materials of the friary, including timber, stone tile, slate, glass, worn paving stone and gravestones, but does not mention any bells. These items were valued at £56 13s 8d, with the lead an additional £4 0s 2d.Footnote 62

Some details of the friary are preserved in documents of the late 1530s and 1540s, written by officers of the Court of Augmentations who administered the Dissolution, such as a survey known as ‘particulars for grant’, drawn up in 1544.Footnote 63 Next to the friary church, located close to the Bene’t St/Wheeler St frontage, lay the cloister with its dortor (dormitory) and fraytre (refectory), with the friary kitchen nearby. Beyond the cloister was a house called ‘le priors lodging’, which had its own two-storey kitchen annexe, an adjacent storeroom and a garden. There was also a second building known as ‘Clyftons lodginge’, again with its own garden.Footnote 64 The friary had a series of gardens, with the principal one known as ‘le Covent Garden’, another that contained a columbare (dovecote) and one described as an ortus, suggesting a horticultural garden for growing food and medicinal plants. There are also six ‘stables’, this probably refers to stabling spaces in one or two stables rather than six separate buildings. The friary was bounded by a precinct wall and was entered by two gates: one on the north side by Peas Hill and the other on the south side of the precinct giving access to the King’s Ditch. A gate here was required by the terms of a thirteenth-century mortmain licence and is shown on Lyne’s view of 1574.

In the fourteenth century at least one of the friary’s plots on Free School Lane was split, by taking the rear of the messuage for the friary precinct but keeping the house on the frontage for rental income.Footnote 65 In the early sixteenth century, the town owned four properties described as ‘near the Austin Friars wall’ that they leased. In 1539 the ex-prior paid 10s as rent, and fourteen other individuals paid rents of £4 19s 8d (see supplementary material, table 2).

MENDICANT IDEALS AND ANTI-FRATERNAL CRITICISM

As already mentioned, the defining aspects of the mendicant orders including the Augustinian friars, particularly in contrast to their Benedictine and Cistercian monastic predecessors, were the commitment to poverty, the mobility of its members combined with the international nature of the orders and the urban locations of most friaries. The success of the mendicant orders provoked contemporary criticism, described by historians as anti-fraternal or anti-mendicant writing.Footnote 66 In the thirteenth century the friars’ rapid growth in the University of Paris caused some academic tensions and, as the roles of the friars began to impact on the parish priests, criticism mounted. In England in the 1350s, Richard FitzRalph, bishop of Armagh, revived the earlier anti-fraternal attacks. He accused friars of pride and avarice in their association with the rich and the nobility, and he argued that mendicancy was unlawful as sinning friars could not perform valid sacraments. FitzRalph’s work influenced the theology of John Wycliffe and the literature of Langland and Chaucer.Footnote 67 Academic criticism of the friars was made in fourteenth-century Oxford and may well have been shared by some Cambridge academics.Footnote 68 However, the ordinary townsmen and women of England continued to support the friars, listening to their preaching and going to friars for confession, and countless English wills record donations to the friars to pay for spiritual services at funerals and for commemorative masses after death. Without necessarily supporting either stance, both mendicant ideals and anti-fraternal criticism provide useful contemporary viewpoints through which to consider the archaeological remains.

FitzRalph accused the friars of building ‘fair minsters and royal palaces’, but not helping with the repair of parish churches.Footnote 69 A later critic, John Gower (c 1330–1408), argued that ‘their devotion aims at ornamentation of a church, just as if such things possess the marks of salvation’.Footnote 70 Though attentive to the physical beauty of the church, the friars are ‘unfeeling toward its spirit … so the friars’ pious devotion is outwardly plain to see, but the vainglorious spirit of their heart lies within them’.Footnote 71 A church built for them ‘towers above all others; they set up stones and are highly fond of carved wood. … Folding doors with elaborate porticoes, halls and bed chambers so numerous and various you would think it a labyrinth. Indeed, there are many entrance ways, a thousand different windows. Their house is to be an extensive structure, a house supported by a thousand marble columns, with decorations high on the walls. It is resplendent with various pictures and every elegance … every cell in which a worthless friar dwells is beautiful, decked with many kinds of rich carving’.Footnote 72 John Wycliffe (c 1320s–84) in his 1380 Objections to Friars included a section (chapter 17) on ‘Their Excess of Buildings of Great Churches and Costly Houses and Cloisters’, arguing that they ‘build many great churches, and costly waste houses and cloisters’.Footnote 73 Although most attention was focused upon friary churches, some sources, such as the late fourteenth-century Pierce the Ploughman’s Crede, emphasise that the cloisters were as ornate as the church.Footnote 74 Various anti-fraternal authors argue that ornate decoration sometimes becomes the worship of graven images and idolatry of wooden or stone statues, stained glass windows and tapestries. Decorated glass attracted particular ire. In The Vision of Piers Plowman of c 1370–90 a Franciscan friar tells Lady Mede: ‘“We have a window in the works, already way over budget, if you would like to glaze the gable and engrave your name there, your soul shall surely ascend celestially” “Oh if I knew that”, said the woman, “there wouldn’t be a window or an altar that I wouldn’t make or mend and adorn with my name, so that everyone would see I am a sister of your house”.’Footnote 75

The Augustinian friars definition of poverty was less austere than some other mendicant orders, particularly the Franciscans. Its principal emphasis was on personal poverty rather than institutional poverty, so architecture was largely excluded. The fourteenth-century window fragments associated with the church can be described as curvilinear or flamboyant. Although we are not comparing like with like, the open cloister had a moulding from a quite different architectural tradition, much simpler and more modest than the church. The stylistic distinction between the cloister and the church may well be linked to mendicant ideals and practice (see below). The international nature of the order does not find any clear architectural expressions. In terms of style, and more particularly the material employed, the emphasis is on the local context, as the types of stone and ceramic tiles used were those employed locally in institutions of all kinds. The architectural elements investigated are also not distinctly urban. They are paralleled in rural religious institutions. There are elements of the Cambridge Austin friars that were attacked by anti-fraternal critics. The friary church with its flamboyant or curvilinear windows may have attracted their ire, as would the glass roundels with the initials of benefactors (see fig 17.1 and 17.2). The painted stonework and plaster (see fig 19.2 and 19.3) might also have been criticised.

Fig 17. Decorated window glass from 1908–9 investigations, stylistically fourteenth–fifteenth century and probably all from the Cambridge Austin friars of c 1380/1420–1538: 1) green glass roundel, with faint traces of paint forming a letter or knotwork design, fourteenth–fifteenth century Z41520.1; 2) green glass roundel, with faint traces of paint forming a letter or badge, fourteenth–fifteenth century Z41520.10; 3) blue glass complete circular pane or roundel with flower and dot design in brown/black paint, fourteenth century Z41520; 4) incomplete blue glass roundel or circular pane with flower design in black paint, fourteenth–fifteenth century Z41520.133; 5) roundel or circular pane of flashed ruby over very pale green ‘white’ with scrollwork in dark brown/black paint, fourteenth–fifteenth century Z41520.135; 6) pale green ‘white’ complete pane with brown painted foliage, fourteenth–fifteenth century Z41520.9; 7) colourless ‘white’ complete piece of painted brown foot, fourteenth–fifteenth century Z41520.4; 8) pale green ‘white’ almost complete censer, a container in which incense is burnt during a religious ceremony, design in brown paint and yellow stain, fourteenth–fifteenth century Z41520.5. Images: Cambridge Archaeological Unit, images of glass discovered in 1908–9 courtesy of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge.

Fig 18. Reconstruction drawing of friary cloister and church c 1500 facing west. Image: produced by Mark Samuel for the After the Plague project.

Fig 19. Sixteenth-century material from the Cambridge Austin friars: 1) pale blue/green glass curved rectangular pane with some patination and pitting, reddish brown painted enamel centre with single line border and clear dot and cross design, probably early sixteenth century Z41520.60; 2) fragment of finely moulded plaster that is architectural in character with moulding lines and rosettes. Whitewashed with gold and red paint over. Probably part of a cornice, Gothic in character suggesting an early sixteenth century date <462> [3555] F.728; 3) triangular shaped Clunch fragment of sculpture with gold and red paint outlined in black <115> [1010] F.103. Images: Cambridge Archaeological Unit, image of glass discovered in 1908–9 courtesy of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge.

DISCUSSION

Only a small portion of the precinct of the Cambridge Austin friars have been archaeologically investigated, and the fragments of stonework, window glass, floor tile and other items represent only a tiny proportion of the material originally present. Although these limitations must be recognised, the investigations of 1908–9 and 2016–19 mean that elements of the friary can now be clearly understood. The friary was established in the 1280s on a densely occupied urban site, although details of the late thirteenth–early/mid-fourteenth century layout and buildings are scanty. Reused architectural fragments indicate the existence of substantial and impressive stone buildings, while other materials indicate the presence of decorated windows and a range of glazed crested ridge tiles. In the mid-fourteenth to early fifteenth century there was a prolonged campaign of claustral construction, the location and layout of these cloisters has been identified and the architectural nature of the cloister arcade revealed. Broadly, the cloister design and style emphasise simplicity, security, strength and compact design that was built so that two floors of accommodation could be provided above. As such it could be viewed as an expression of mendicant ideals and reflecting the accommodation requirements of the friary as a teaching institution. Also in the mid-fourteenth century, the friary church went through a substantial phase of rebuilding, with evidence for a range of windows. These can be characterised as curvilinear or flamboyant, stylistically quite different from the cloister and arguably less in keeping with mendicant ideals. The church represents the publicly visible and accessible outward facing aspect of the friary, while the cloister was a more private space, and the architectural differences may reflect tensions or compromises between mendicant ideal and reality. In Ireland, a tradition of single-arch unglazed arcades continued until the Reformation, although little documentation for the Irish examples survives. The styles were simple; Muckross Abbey (Co. Kerry), Askeaton (Limerick) and Ennis (Co. Clare) display massive ‘monolithic’ construction with (functionless) coupled colonnettes. These abutted sloping buttresses of unusual form that terminated at the level of the first floor with further chambers above. The relatively well-dated Cambridge example adds to a thinly populated corpus, and the absence of defined capitals and bases even suggests a position in a ‘typology’. In mainland Britain, the open single-arch arcade was usually replaced with glazed tracery. The Cambridge Augustinian friary arcade seems to be a rare continuation of earlier ascetic traditions.

The floors of the friary employed a range of types of decorated tiles and there were also decorated windows. The cloisters and church then appear to have continued in use with only minor modifications until the Dissolution. To the south of the cloisters more buildings were added in the fifteenth century, potentially indicating the construction of a second cloister. Following the Dissolution there were major changes to the site, but significant parts of the architecture continued in use until the late sixteenth to early seventeenth century, with some elements surviving into the early twentieth century.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Craig Cessford directed the 2016–19 archaeological excavations and later phases of analysis and is the principal author of this publication. The architectural mouldings were studied by Mark Samuel, FSA, and he contributed greatly to the wider architectural interpretation of the remains. The window glass was studied by Vicki Herring, and the ceramic building materials by Philip Mills. Rosemary Horrox kindly made her research on the documentary sources available, with additional work undertaken by Nick Holder, FSA.

The 2016–19 excavations and this publication were undertaken on behalf of the University of Cambridge and its Estate Management division. Andy Thomas (Cambridgeshire Historic Environment Team) monitored the project. Alison Dickens and Ricky Patten have been the project managers for the CAU.

The graphics are the work of Laura Hogg, with advice from Andy Hall and incorporating work by Vicki Herring and Bryan Crossan. Photographs are by Dave Webb and Craig Cessford. Imogen Gunn facilitated study and photography of the material held by the University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S000358152300001X.

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abbreviations

- AF

-

architectural fragment

- CAU

-

Cambridge Archaeological Unit

- CPR

-

Calendar of Patent Rolls

- TNA

-

The National Archives, London