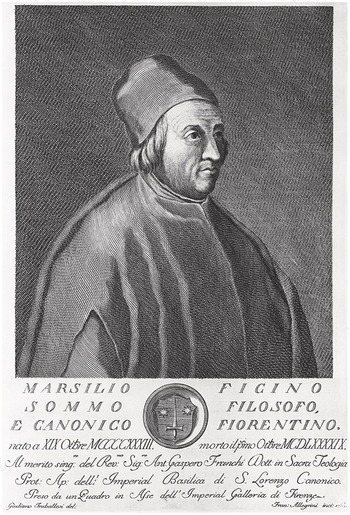

Around 1460, the philosopher Marsilio Ficino (1433–99) received a message from his patron, Cosimo de’ Medici (1389–1464), the most powerful man in the Italian city-state of Florence. Up to this point Ficino had been hard at work translating the works of the ancient philosopher Plato (c. 424–c. 348 BCE) from their original Greek into Latin, but his patron had other ideas. He wanted Ficino to begin translating a different Greek manuscript, one that Cosimo had only recently acquired. Obligingly, Ficino set Plato aside and turned his attention to this new work. He soon realized that he had stumbled across something very important (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Portrait of Marsilio Ficino by Francesco Allegrini, 1762.

The works that Ficino translated became known as the Corpus Hermeticum, and they contained the recorded wisdom of a mysterious figure known as Hermes Trismegistus or Hermes “the Thrice-Powerful,” a contemporary of Moses and a sage of unparalleled learning who had lived thousands of years earlier in ancient Egypt. His writings promised to reveal the secrets of the universe to those willing to learn, and this soon included Ficino, who became a passionate advocate for the ideas of Hermes and was instrumental in disseminating them throughout Renaissance society. Ficino, along with many others, believed that the Hermetic writings contained traces of ancient, uncorrupted wisdom that might restore human understanding to the heights achieved by those, long ago, who had known God and His creation in ways since lost to modern people.

The tradition disseminated by Ficino is known as hermeticism, and it incorporated both philosophical lessons on the nature of the divine as well as hands-on instructions for magical work. Both hermeticism and the other tradition we explore in this chapter, cabalism, are examples of learned magic – that is, magic studied and practiced by the educated elite. This is very different from the magic worked by healers, midwives, and others in small communities and rural areas across Europe, practices usually labeled by historians as “folk magic.” Learned magic had its roots in the distant past, and those who embraced it did so with the hope that they would uncover secrets and mysteries that would transform European society forever. This idea was so powerful and compelling that it fundamentally altered intellectual life in Europe and continues to inspire people today.

In this chapter we examine both hermeticism and cabalism in an attempt to understand why they captivated European people for hundreds of years, before turning our attention to the figure of the magus, the learned magician who seeks to pull back the veil that obscures the workings of the universe. Some, like the English magus John Dee (1527–1608), built their reputations and identities around their reputed ability to uncover nature’s secrets, but there was also widespread anxiety about the lengths to which these magicians might go in pursuit of knowledge. That anxiety was perhaps most memorably expressed in the fictional tale of Faustus, who trafficked with demonic forces and paid the ultimate price. In fact, both Dee and Faustus came to unfortunate ends, and both are useful in placing learned magic in a wider context.

Learned Magic before Ficino

Marsilio Ficino was far from the first philosopher to write approvingly about the varied uses of magic. The practice of learned or scholarly magic existed centuries before the translation of the Corpus Hermeticum, most commonly among members of the clergy. The historian Richard Kieckhefer has made a close study of a fifteenth-century manuscript that he calls the “Munich handbook,” a learned treatise that describes how to summon demons and work such varied magic as inducing love in women and becoming invisible. Because this text was written in Latin and demonstrated a good understanding of Christian liturgy and ritual, Kieckhefer believes that its author was a priest or monk – few others would have the theological and intellectual sophistication to create the complex rituals and ceremonies described in the handbook. In fact, because members of the clergy generally were educated in the Middle Ages, Kieckhefer argues that they were the most likely practitioners of learned magic, including magic that employed demons. The magical tradition of necromancy, which in classical antiquity had referred to speaking with the dead, was reimagined in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries as magic that trafficked exclusively in the summoning of demons. Thus, combining rituals of Christian exorcism and astral or astrological magic inherited from Arabic writers, medieval necromancers were well-educated men who supposedly summoned demons in order to accomplish a wide range of tasks. The Munich handbook studied by Kieckhefer is a clear descendent of this tradition.

Not all learned magic was necessarily demonic, however. Beginning in the twelfth century, Europe experienced an influx of ideas and texts from the Islamic world as part of a lengthy process of cultural exchange. This influx helped to create the first universities in Europe and set the stage for the arrival of the Renaissance, which we will explore shortly. Another consequence, however, was a shift in learned attitudes toward magic. Prior to the twelfth century, almost all theologians and philosophers believed that magic involved demonic intervention of some kind. The magical practices described in ancient literature, such as the sorceress Circe transforming men into animals in Homer’s Odyssey, or the marvels and miracles ascribed to pre-Christian deities were understood by medieval Christians to be morally wrong and demonically inspired. Beginning in the twelfth century, however, the works of influential Islamic philosophers presented a different perspective to European scholars. Some of these authors wrote approvingly of magical practices that had nothing to do with demons and that operated by means of natural forces alone. This included the astral or celestial magic – which drew upon the hidden forces and virtues of the planets and stars – that was eventually incorporated into medieval necromancy as well as a wide range of other practices and traditions that sought to harness nature’s unseen power in acts of natural magic. At the height of the Middle Ages, in the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, significant numbers of educated men devoted considerable time and energy to the study of natural magic, sometimes over the objections of contemporaries who still believed all magic to be fundamentally demonic in origin.

This was the backdrop against which Ficino’s recovery of hermeticism took place. The Hermetic Corpus, along with a series of other works also attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, described a way of understanding the cosmos that combined religion, philosophy, and magical practice into a coherent whole. For Ficino and other proponents of hermeticism, there was nothing morally suspect about these practices; they were resolutely natural. Not everyone agreed, however, and practitioners of learned magic in the Renaissance had to contend with the same suspicions of demonic collaboration faced by learned magicians in the Middle Ages.

The Renaissance

Ficino’s efforts to translate the Hermetic Corpus, and Ficino himself, were both products of the Renaissance. More particularly, Ficino’s life and works exemplify the intellectual movement known as humanism, which sought to recover and revive the “golden age” of classical antiquity. Together, both the Renaissance and humanism set the stage for Western modernity as we know it today.

Speaking broadly, the Renaissance was a sweeping cultural movement that began in the fourteenth century and changed European society in profound and lasting ways. Because it took hold at different times across Europe, historians disagree as to when the Renaissance ended, but it persisted at least into the sixteenth century when Europe entered what is known now as the early modern period. The word “renaissance” comes from the French term for “rebirth,” which leads to an obvious question: What exactly was reborn? The answer provides us with a crucial insight into premodern Europe, because what the educated classes were so eager to revive was the culture of classical antiquity. This means the culture of the ancient Greeks that existed during what is known as the Hellenistic period, beginning around the year 300 BCE, and of their successors, the Romans, who established the Roman Empire around the year 27 BCE and absorbed huge amounts of Greek learning, art, and culture over the following centuries.

The Renaissance, then, was an attempt to restore to Europe the art, ideals, and learning of the ancient Greeks and Romans. This fascination with the distant past defined not just the Renaissance itself, but the entirety of learned culture in premodern Europe as well. From the fifteenth century onward, the educated classes of European society devoted themselves first to the recovery of antiquity and, later, to efforts to improve upon or escape from it.

It makes sense that the Roman Empire was a powerful source of attraction and myth for premodern people, many of whom in the fifteenth century lived among tangible remnants of that once-glorious past – everything from the crumbling infrastructure of roads and aqueducts to the dilapidated ruins of a thousand settlements. At its height, around the year 120 CE, the Roman Empire stretched across a vast area and contained about 20 percent of the world’s population, around 90 million people. To the west, it reached into the British Isles and what is now Spain and Portugal; to the south it covered much of northern Africa, including Egypt; and to the east it encompassed a large portion of the modern Middle East, including Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq and Syria) and what is now Israel. It was a diverse and multicultural empire, and among its many achievements was a robust and vibrant tradition of philosophical thought inherited from the ancient Greeks (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 The Roman Empire at its height in the second century CE.

In time, however, political instability and the sheer size of the Empire made it impossible to govern effectively, and around the year 330 CE it was effectively divided into two when the emperor Constantine the Great (272–337) moved the capital of the Empire to the city of Byzantium and renamed it Constantinople (known today as Istanbul, the capital of Turkey). Still governed from the city of Rome, the Western Empire slowly declined, a process hastened by the brutal sack of Rome itself by the barbarian hordes of the Visigoths in 410 CE and then the Vandals in 455 CE. By the year 495 CE, the Western Empire had fallen into ruin. By contrast, the Eastern Empire (also called the Byzantine Empire) flourished for another thousand years.

It was the Eastern Empire that safeguarded the remnants of ancient learning, most of which had been written first in Greek. This was also the language of government, religion, and learning in the Byzantine empire, as well as the language spoken daily by millions of imperial citizens, and it was in Byzantine libraries and monasteries that ancient Greek ideas were copied and preserved. Meanwhile, for people living in the ruins of the Western Empire, basic literacy in Greek had died out in what historians in the nineteenth century grimly referred to as the “Dark Ages,” the period that began with the sack of Rome in the fifth century and ended more than 500 years later with the social and intellectual flourishing of the Middle Ages. For many people living in western Europe, the learning of the ancients might as well have disappeared forever.

Beginning in the seventh century CE, the Byzantines went to war with the forces of the Rashidun Caliphate, the first Islamic state founded after the death of the prophet Muhammad (c. 570–632). The Caliphate extended across much of what is now the Middle East before it was succeeded by the Umayyad Caliphate (founded in 661 CE), which expanded its territories to encompass more than 60 million people. The Caliphate warred on and off with the Byzantines but tolerated the presence of Christians and Jews within its borders. Despite the tensions between the two empires, people created both formal and informal avenues of communication and commerce. Merchants, scholars, and government officials on each side learned the language of the other, and so when the philosophical and medical works of classical antiquity eventually made their way into the Caliphate, Islamic scholars fluent in Greek began to translate them into Arabic.

The movement of classical European learning into the Islamic world sparked a period of intellectual flourishing that lasted for centuries. Under the leadership of the Abassid dynasty, which took control of the Caliphate from the Umayyads around the year 750 CE, a vast translation movement began. The House of Wisdom, or Bayt al-Hikmah, was established in Baghdad in the early ninth century and became arguably the most important site of learning in the entire world. Scholars translated many works of classical antiquity into Arabic and then disseminated them throughout the Islamic world. Islamic philosophers, naturalists, and physicians appropriated Greek learning and then proceeded to build their own important and original contributions on those foundations. Ibn Rushd (1126–98), known in Europe as Averroes, was an expert in Islamic law who also wrote treatises on mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and philosophy, while the ingenious Ibn-Sīnā (c. 980–1037), called Avicenna in Europe, produced hundreds of works that included some of the most important medical treatises in history, many of which were still taught in European universities in the sixteenth century. They were preceded by al-Kindī (c. 801–73), sometimes known in the Latin West as Alkindus, who was one of the first to champion the study and adaptation of Greek and Hellenistic ideas and was later revered as one of the greatest Islamic philosophers. Other prominent Islamic thinkers who emerged during this “Golden Age” include the influential physician al-Rāzī or Rhazes (854–925), al-Farabi (c. 872–950), who wrote commentaries on the philosophies of Plato and Aristotle, and al-Bīrūnī (973–1048), who was a mathematician and geographer. Alongside many others, these scholars built upon and added to Greek philosophy and medicine across hundreds of years.

But how does any of this matter to the Latin West, or to the Renaissance? The answer to that lies in the eventual reach of the Islamic Caliphate. In the eighth century, the Umayyad Caliphate expanded into the Iberian peninsula – what is now Spain and Portugal – and thereby came into direct contact with western Europe. Trade sprung up between these two cultures, and trade of course requires that each side understand the language of the other. When some in western Europe became fluent in Arabic, they were able – at last! – to read the translated works of Greek antiquity. Beginning in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, many of these works were translated from Arabic into Latin (the primary language of learning and scholarship in the west, one of the lingering remnants of the Roman Empire), until finally, after hundreds of years and a very circuitous route, the writings of the ancient Greeks finally returned to Europe. Fluency in Greek became possible again, leading western scholars to seek out Greek manuscripts still held in the east, and eventually we find ourselves in fifteenth-century Florence with the mysterious Greek manuscript that Cosimo sent to Ficino.

The recovery of ancient learning not only laid the foundations for the Renaissance but also encouraged the rise of universities, which emerged in the eleventh and twelfth centuries as centers for the translation and exchange of ideas. In fact, with the benefit of hindsight we can appreciate how thoroughly the study of classical society led to innovations that remain with us today: styles of architecture that are still visible in cities around the world; artistic practices like the use of linear perspective which transformed European art; changes to European language and education that led to the formation of distinct social classes; and new ways of studying both the natural world and the human body. Ultimately, the recovery of ancient learning altered the very fabric of European life as profoundly as it had transformed the Islamic world.

Humanism

At its most basic, humanism was the study of classical antiquity, but in fact it was far more ambitious than that. Humanists in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries wanted to revive classical antiquity, not just study it. They believed that it was not enough to read and learn the ideas of classical antiquity – it was also necessary to live according to the moral philosophies and precepts passed down by classical authors. For many humanists, a virtuous life (or as many ancient philosophers put it, a life lived well) went hand-in-hand with the ability to convey one’s thoughts and opinions with eloquence and clarity. They also believed that a citizenry that was educated and articulate was the ideal environment in which to revive the social and political ideals that had flourished in the classical world. Accordingly, humanism focused enormous attention on education and particularly on the subjects that had formed the trivium, the most basic level of education in classical antiquity: grammar, rhetoric, and logic.

Given special attention by Renaissance humanists were the disciplines of grammar and rhetoric, which were greatly expanded as part of the humanist curriculum and which became known as the studia humanitatis, the predecessor to what we today call the humanities. The study of logic gradually fell away, at least within this new curriculum of study, which was then expanded by the addition of history and philosophy, particularly moral philosophy. Poetry also became a subject of intense study as it was seen as the natural extension of rhetoric, the goal of which was to refine one’s speech and writing so as to persuade or move an audience. Accordingly, the classical figure most revered by early humanists was the Roman orator Cicero (106–43 BCE), famed during his lifetime for his eloquence and his mastery of the Latin language.

Renaissance humanism had its roots in Italy, and many important Italian cities became cultural centers for the rise of humanism and the wider movement of the Renaissance. It is no accident that when we study Renaissance art, architecture, and literature today, we usually focus first on the works and ideas of the Italian people. Some of the most important early humanists were Italian, including the scholar often referred to as the “father of humanism,” Francesco Petrarca (1304–74, widely known today as Petrarch), and they included not just philosophers but also poets and writers. As humanism spread outward from Italy other famous humanists emerged, most prominently the Dutch thinker Erasmus (1466–1536), sometimes called the “prince of the humanists.”

Humanism soon integrated itself into the mindset of Europe’s educated classes. Humanist educations became common among Europe’s elite, and with this new style of education came a range of novel and sometimes controversial perspectives. For one thing, most of the classical authors read and idolized by Renaissance humanists had lived before the appearance of Christianity and so were regarded as pagans, a general term that came to mean “pre-Christian.” Some, like Plato and his followers, held ideas that could be reconciled fairly easily with Christianity – for example, Neoplatonists who lived in the early centuries of the Common Era such as Plotinus (c. 204–70) and Iamblichus (c. 245–c. 325) wrote about the divine in terms that made sense to later Christians. But many classical authors held ideas that were different from, or even incompatible with Christianity, and the Catholic Church was understandably suspicious of an education that revolved around pagan or pre-Christian ideas. Furthermore, some classical authors – Cicero chief among them – had written against tyranny and praised republicanism, a system in which citizens effectively control their own state. For many early humanists, living in European monarchies that were certainly not democratic republics, the more egalitarian political vision supported by these classical authors was very appealing. This led to rising political tensions as humanist ideals spread across Europe, with long-lived consequences. There are clear connections between the rise of humanism in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and the modern idea of the state that began to emerge during the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century, leading to the political upheavals of the French Revolution and the American War of Independence.

As the word “humanism” implies, its primary focus was people. Modern historians generally see humanism as fundamentally concerned with the rights, freedoms, and expression of the individual, a focus still embraced today by the humanities. At the same time, however, the humanist tradition encouraged not just the revival of classical ideas but also their critique. Humanist scholars did not just blindly copy the beliefs and practices of their classical ancestors; instead, they studied, questioned, and sometimes disagreed with classical ideas. This aspect of humanism will become a central part of later chapters in this book, when we meet individuals who wanted to reform and improve upon the practices of antiquity. This interesting identity, caught somewhere between a desire to revive classical antiquity and an eagerness to reform it at the same time, exemplifies the kind of critical thinking still taught in the best traditions of humanistic education today.

The Original Wisdom

This is the complicated backdrop against which the learned traditions of classical magic emerged during the Renaissance. The ideas recovered by humanists and other scholars were not focused entirely on poetry or architecture or rhetoric; they also included ancient philosophies that ranged from theories about the natural world to expressions of spiritual and religious doctrine. Both of the traditions we examine in this chapter, hermeticism and cabalism, rest somewhere between natural philosophy and religious belief, partaking of both in different ways. This is one reason why they were so attractive to premodern people. They offered wide-ranging and comprehensive ways of understanding the whole universe, from the mundane phenomena of the everyday world all the way up to God Himself.

Even more significant was the belief that, because these philosophical traditions had ancient roots, they were closer to the original knowledge that humans had once possessed but which had degenerated after humanity’s fall from divine grace when Adam and Eve were punished by God with expulsion from the Garden. Before that expulsion, Biblical scripture records that Adam had named the birds and beasts and fish, a sign to premodern Europeans that he had access to some fundamental, intrinsic knowledge that allowed him to know the true names of things. Whatever mysterious knowledge God had granted Adam and Eve, however, had been withdrawn from them after their transgression in the Garden, leaving their descendants ignorant of the deepest truths about Creation.

This knowledge is known as prisca sapientia, which means “ancient wisdom” in Latin. Most educated people in premodern Europe believed that there was some original wisdom or knowledge available to our earliest ancestors that had been diminished and distorted over the intervening millennia. One of the most important tasks of the philosopher was to recover fragments of that knowledge, and one way to do that was to seek out the teachings of those who lived in ancient times. These older teachings lay closer to the prisca sapientia and were probably less corrupted than the knowledge available in the present. This, in a nutshell, is why the figure of Hermes Trismegistus was so appealing to early modern Europeans. It is also why some Christians became fascinated by the Kabbalah, a form of wisdom passed down through many generations of Jewish mystics and scholars. Both the writings of Hermes and the Kabbalah promised to reveal to Europeans the lost secrets of a distant age.

The idea of an ancient and uncorrupted wisdom was a powerful motivation for many thinkers in premodern Europe, but it was not just a knowledge of philosophy and the physical world that had degenerated with time. Even more important was knowledge of God and the divine, known as theology. According to scripture, Adam had known God in a way that later people could not. He had spoken directly to God in the Garden, and many believed that his understanding of God was as pure and deep as it was possible for human knowledge to be. This kind of understanding was known as prisca theologia. Like the prisca sapientia, it represented a kind of knowledge that was undiminished and uncorrupted, a strain of theology that predated all later religions and therefore unified them. Adam had lost his special connection to God when he was expelled from the Garden, however, and from that moment onward human understanding of the divine had faded, corrupted by error and ignorance. The notion of an ancient theology, more closely connected to that primordial understanding of God, was extremely appealing to premodern people, and only became more so following the religious upheaval and fractures caused by the Protestant Reformation in the early sixteenth century. As with prisca sapientia, the prisca theologia had the potential to radically transform how Europeans understood their world.

Modern society tends to be forward-looking rather than fixated on the distant past, so this interest in ancient knowledge might seem strange to us now. Many premodern Europeans, however, looked around themselves and saw the tattered and faded remnants of a glorious past, one that they wanted desperately to recover. Imagine living in fifteenth-century Rome, among the crumbling ruins of the Empire, or in a remote monastery surrounded by hand-copied texts that were only fragments of a vast body of knowledge long since lost. How could you not hunger to return to a time when philosophy, art, architecture, and theology had been more sophisticated and innovative than anything that existed a thousand years later? To many educated people in premodern Europe, their society seemed only a shadow of the glories of antiquity. That perspective would eventually change but, during the Renaissance, figures like Hermes Trismegistus, whose understanding of God and nature seemed to outstrip anything available in the fifteenth century, were the key not only to recovering the past but to building the future as well.

Hermes and the Hermetic Corpus

When Marsilio Ficino recovered and translated the Hermetic Corpus from Greek into Latin, he did so as part of a larger humanist project intent on reviving classical traditions. He also established the Florentine Academy in his native Florence as an attempt to emulate Plato’s famous Academy in Athens, and he was the first to translate and publish the entirety of Plato’s existing works as well as the works of important Neoplatonists such as Iamblichus and Plotinus, philosophical descendants of Plato who lived in the early centuries of the Common Era. In hermeticism, however, Ficino believed he had discovered a kind of knowledge that was even more important than the writings of classical antiquity.

Recall that Ficino and many others believed that Hermes Trismegistus had been a contemporary of Moses, the prophet who was believed to have lived some 3,000 years before the advent of the Renaissance. This made Hermes an extremely valuable source of knowledge for premodern Europeans. He would have had access to both prisca sapientia and prisca theologia on par with that of Moses himself, and his writings that had survived down into the fifteenth century, when Ficino translated them, represented a potential goldmine of knowledge that had escaped the corruption of time (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Engraving of Hermes or Mercurius Trismegistus. From Pierre Mussard, Historia Deorum fatidicorum, 1675.

References to Hermes, or to shadowy figures who might have been Hermes, exist in writings going back to classical antiquity. In the earliest centuries of the Common Era some authors speculated at length about his origins, pulling together rumors and myths to suggest that Hermes was ancient even by the standards of their time. These early writings claim that he was worshipped as some kind of combination between the Greek god Hermes – the messenger of the gods but also the patron of communication and travel – and Thoth, the ancient Egyptian god of knowledge and writing. During the Hellenistic period (roughly 300 BCE to 30 BCE), when Greece controlled much of modern-day Egypt, it was not uncommon for gods from different pantheons to become associated with one another, a practice that persisted into the later Roman occupation of the Hellenistic world. The figure of Hermes Trismegistus appears to have arisen from this kind of overlapping association, acquiring a reputation linking him to wisdom, knowledge, and magic. While he may have been worshipped as a minor deity in antiquity, however, most Europeans in the Renaissance portrayed him as human, probably an ancient Egyptian priest or sage whose name had become associated with pagan worship.

Importantly, the Egyptian origins of Hermes intersected with a wider European fascination with ancient Egypt that persisted between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries. During this period, numerous Egyptian obelisks covered in hieroglyphs were discovered and excavated from the ruins of ancient Rome. These artifacts had been carried from Egypt to Rome at the height of the Roman Empire, which controlled most of modern-day Egypt, but after the Empire collapsed the obelisks suffered the same fate as most of the ancient buildings in Rome, which is to say they fell over and were buried beneath a new, more modern Rome in the centuries that followed. As they were uncovered, these obelisks were then transported (with great difficulty) to various spots around the modern city and erected once more. Many are still standing today, including one situated in the center of the plaza in front of St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican, the spiritual and political home of the Catholic Church. The enormous expense and labor required to move and restore these remnants of ancient Egypt demonstrates, at the very least, how powerfully Egyptian culture influenced the imaginations of many during the Renaissance. That same influence undoubtedly helped to make hermeticism a topic of intense interest as well.

Following Ficino’s publication of the Hermetic Corpus, hermeticism grew and spread through European intellectual culture. Traces of hermetic ideas and doctrines appeared in works written by dozens, if not hundreds of authors across more than 200 years. But there is an intriguing twist. In 1614, the French scholar Isaac Casaubon (1559–1614) determined that the Hermetic Corpus had not been written at the time of Moses at all. Some of its texts had obvious Hellenistic influences, meaning that they were almost certainly written after the Greeks came to control Egypt and other parts of North Africa and the Near East. That would date these texts to sometime after roughly 300 BCE, much closer to modern times than the empires of ancient Egypt, which had flourished thousands of years earlier. Casaubon was a scholar of the classical world as well as a philologist, or someone who studies the structure of languages, and he found other clues in the hermetic texts that pointed to an origin that was even more recent than the Hellenistic period, something closer to the second or third century CE, meaning that they were compiled during the Roman Empire and after the advent of Christianity. While these texts were still ancient by the standards of early modern Europe, they were no more ancient than the Roman Empire and certainly not the product of a person living and writing millennia earlier than that.

Following Casaubon’s revelation, hermeticism’s influence on European thinking started to wane. Some people, however, remained utterly committed to the hermetic worldview and its philosophy, arguing that Casaubon had simply gotten his dates wrong. Today, most scholars agree with Casaubon that the Hermetic Corpus had its origins in the early centuries of the Common Era and emerged from a turbulent, chaotic mixture of Greek and Hellenistic philosophy, early Christian mysticism, and magical traditions borrowed from different sects in what is now the Middle East. These writings represent the blending of ideas – also known as syncretism – that was common in this period, when people eagerly mashed together the ideas and worldviews of different cultures to create entirely new ways of thinking. Maybe this mixture of so many disparate philosophies, beliefs, and practices is why hermeticism has inspired and intrigued people for hundreds of years.

The Substance of Hermeticism

The question remains, what did people find when they read the Hermetic Corpus that Ficino translated and published? First, it is important to understand that hermeticism was an extremely broad set of beliefs and ideas that combined religion, philosophy, and ancient ideas about magic. In fact, hermeticism does a superb job of demonstrating how these three systems overlapped with one another. If magic is the manipulation of the universe’s hidden forces, then the hermeticist needs philosophy to investigate the universe and reveal those forces, and in doing so comes to understand how and why God created the universe in the way that He did. The true hermetic practitioner, or magus, understands that the cosmos is full of connections and invisible links between different objects, and their job is to use those connections to produce specific effects in the world. In doing so, they come closer to understanding God as Creator, who not only fashioned those connections but also uses them Himself, along with angels, demons, and the Devil. Indeed, as we will see, the figure of the hermetic magus eventually became closely intertwined with the supernatural in ways that sometimes were problematic for practitioners of hermeticism; more often than not, they were feared as the dupes or collaborators of demonic forces.

Modern scholars have made a distinction between two different kinds of hermetic writings. One group of texts, those first translated by Ficino in the fifteenth century, are more philosophical and theological in their focus. Ficino called this collection of fourteen books or chapters the Pimander, a term still used today to describe this relatively limited piece of hermetic writings. The Pimander describes the religious worldview of a sect or community that flourished in classical antiquity, and also lays out the philosophical foundations of that worldview. These texts are deeply pious, referring continually to a single God and building a philosophy of nature and life founded on the worship of this deity. This is one reason why these particular texts were so appealing to Europeans living in the Renaissance. Though everyone assumed these were pagan works, written long before the advent of Christianity, they were actually easy to reconcile with a Christian worldview because their religious elements appeared to parallel the basic tenets of Christianity. The pagan Egyptian sage Hermes revered a deity very similar to the Christian God, not only making Hermes a “good” pagan by European standards but also seeming to confirm the truly ancient roots of the Christian faith, since the hermetic texts were thought to embody an understanding of the divine, the prisca theologia, that stretched back to the earliest years of humankind. Now, of course, we understand that the Hermetic Corpus aligns so well with Christianity for at least two main reasons: because it was written after Christianity had appeared in what is now the Middle East, not before; and because its authors were inspired by some of the same philosophies and beliefs that also inspired the earliest Christian writers.

While there are references to astrology in the texts that Ficino translated, there is virtually nothing about magic. Instead, the works included in the Pimander are primarily theoretical and philosophical treatises; they describe ideas rather than their direct application. This is less true of another group of texts that began to circulate in Europe after Ficino’s original translation appeared. These works are steeped in occultism and include numerous references to alchemy – the manipulation and transmutation of matter – as well as to forms of magic including divination and astrological magic. This second set of texts mentions Hermes and so are thought of as “hermetic,” but they were probably written later than the theological texts, or by different people. Their emphasis is more practical; they describe how to accomplish specific tasks using the knowledge and wisdom passed down from Hermes.

There is still much that we do not know about the origins of the Hermetic writings. For one thing, these texts are extremely old and survive only in fragments of the originals or in references to destroyed or missing texts mentioned by authors of other works. For another, the Hermetic Corpus was the product of many people writing across several centuries. There is no one or universal perspective because there was no single author, or even a small group of authors. Instead, we have a sprawling collection of ideas that are connected only by references to Hermes as well as by some shared theological and philosophical arguments. If we accept this rough division of Hermetic texts into theoretical or philosophical on the one hand and practical or magical on the other, then we effectively have two different schools of thought that overlapped in some small but important ways.

One important point of overlap is the idea of salvation and empowerment through knowledge of the divine, which the historian Brian Copenhaver has described as part of his modern translation of the Hermetica. The mysticism present in these writings encourages the reader to contemplate the divine and, through that contemplation, comes to understand the world. This idea was itself appealing to many premodern Europeans because it encouraged a pious and religious approach to the study of nature and to philosophy more generally. But this idea also colored the kind of magic that came to be associated with hermeticism in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It was a magic that was both philosophical and theological in scope: it, too, encouraged the contemplation of the divine as a form of empowerment that the magus could then use to create change in the physical world. For some, the Hermetic magus ascended a metaphorical ladder that stretched between God and the world; the higher he climbed, the more he understood and the more he was able to do with the aid of magic.

This idea of the magus ascending toward a divine understanding of the universe made sense to many people. It suggested that a pious and thoughtful person potentially could do amazing things once they grasped how everything fit together. At the same time, however, it is not difficult to see how this kind of thinking might have made some people uneasy. The suggestion that someone could use pagan knowledge to better understand the mind of God struck some Christians as a problematic, even blasphemous idea. The writings of some hermeticists also hinted that the ascended magus was capable of almost anything; in theory, understanding the hidden forces that crisscrossed the universe would give someone power that approached that of God Himself. To many, that was a dangerous proposition.

What did hermeticism look like in practice? Unfortunately, there is no one answer. Because hermeticism was so broad and represented a wealth of different and overlapping perspectives, the ways in which people adopted and disseminated it also varied widely. For example, the Italian philosopher Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–94) was known to Marsilio Ficino and absorbed at least some hermetic ideas while living in Florence. He believed that there was a fundamental connection between a wide range of intellectual traditions, from the philosophy of Plato to the medieval Christian commentaries of Thomas Aquinas (1225–74) to the writings of Hermes. All of these traditions, he argued, had stumbled upon truths about the world, and so all of them, to varying degrees, shared something of the prisca sapientia, that first and original knowledge about Creation once granted to Adam in the Garden. Pico’s willingness to place Christian philosophy alongside the writings of the pagan Greeks and even the Arab infidels led to accusations of heresy and a papal ban on any public discussion of these ideas, but his belief in a shared foundation between these different traditions was very reminiscent of Ficino’s own ideas.

Over the course of the next century or so, hermeticism grew and evolved until it became a sprawling, often untidy collection of ideas, beliefs, and claims. The term “hermetic” became increasingly common in early modern texts, but those texts could, and often did, contradict one another. Hermeticism, as well as the figure of Hermes himself, came to represent very different things to different people. For example, the Venetian philosopher Francesco Patrizi (1529–97) helped to disseminate hermetic ideas to wider audiences in the generation after Ficino, and also wrote approvingly of the close links between Platonic philosophy and Christianity evident in the Hermetic writings. Like many others who lived and wrote in the turbulent decades of the sixteenth century, during which the Protestant Reformation fractured Christianity seemingly beyond repair, Patrizi wanted to find evidence of a pure, uncorrupted theology that might heal the divisions that now separated Catholics from Protestants. For him, as for both Ficino and Pico before him, hermeticism offered a way to uncover ancient truths about God.

Robert Fludd (1574–1637), an English physician and philosopher, was heavily influenced by Hermetic ideas when he wrote about the elaborate harmonies that spanned the cosmos and the alchemical processes capable of breaking down material substances to expose their fundamental natures. Though very different from Patrizi in almost every way, Fludd was also committed to the search for theological and religious truths in the study of the natural world. He created what he called a “theophilosophy” to express this, and assigned supernatural causes to natural phenomena in ways that made many of his contemporaries uneasy – for example, he speculated that the angels themselves transmitted forces like magnetism from one object to another. Long after his death, Fludd was revered by some as one of the most important hermetic philosophers in early modern Europe, and his vision of a universe in which everything was connected to everything else appealed to many.

Given its emphasis on original wisdom and knowledge, perhaps it is not surprising that hermeticism managed to overcome at least some of the strife and division caused by the Reformation and the fracturing of Christianity. Fludd was an unapologetic Protestant who wrote freely against Catholic dogma, but there were hermeticists among Catholics as well. The Jesuit philosopher Athanasius Kircher (1602–80), living in the heart of Rome and writing with the express permission of the Catholic Church, made no secret of his admiration for Hermes. In his work on the magnet, first published in 1641, Kircher claimed that everything in the world was connected by “secret knots” and included lavish images in which metaphorical chains bound together disparate things. Tellingly, he also ended that same book by calling God “the great Magnet” whose divine love was the force that drew everything together. In some ways, Kircher’s vision of God was not all that different from the divine being described by Hermes himself.

Patrizi, Fludd, and Kircher were very different people who lived and wrote in very different contexts, yet all of them were drawn to the idea that deep, fundamental truths about the universe had been recorded in the Hermetic Corpus. Whether seeking the ancient roots of Christianity or unlocking the means to manipulate nature using the unseen correspondences that connected all things, these and many other thinkers were drawn to the mix of philosophy, religion, and magic that characterized hermeticism. This tradition confirmed for many people that prisca sapientia and prisca theologia were real, and that their recovery would illuminate the truths of the universe. Hermeticism also encouraged educated Europeans to see magic as connected to the divine and, more broadly, the supernatural world; it suggested that the study of nature’s hidden forces and powers could be both a spiritual endeavor and a path to tremendous power.

The Cabala

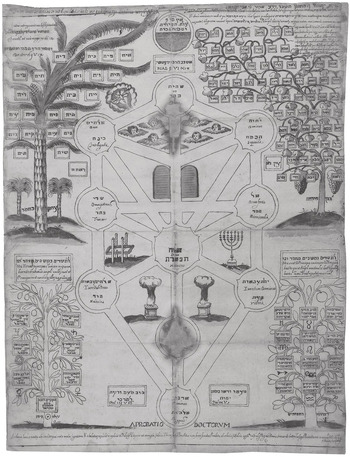

The word “cabala” usually refers to the Christianized form of the Hebrew Kabbalah, a mystical and esoteric form of knowledge with its roots in Judaism. For centuries people have used these traditions to interpret religious and mystical texts, gaining access to secret or hidden knowledge contained in these works. Jewish scholars have speculated that the origins of the Kabbalah date back to Moses receiving the Law (usually known in Christianity as the Ten Commandments) from God. When God revealed the Law to Moses, He also revealed the secret meaning of the Law which became the Judaic tradition of the Kabbalah. Its practitioners believe that the revealed word of God as recorded in the Law and also in the Hebrew Bible, or the Tanakh, contains secret and hidden wisdom that can be discovered only by the study and manipulation of these texts. This emphasis on the written word and, by extension, the letters of the Hebrew alphabet reflects a belief in the power of language as well as the idea that, for God, words had generative power – after all, scripture records that God spoke the universe into existence when He said, Fiat lux, or “Let there be light.” There are also kabbalistic traditions that focus primarily on the ten sefirot, which are interpreted sometimes as manifestations or emanations of God’s various attributes and, at other times, as ten different names for God. Together, the sefirot form the foundation of the physical universe; they are the means by which God created everything but also part of God Himself. By studying the sefirot, the kabbalist comes to understand both God and His creation (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 A seventeenth-century depiction of the Arbor Cabalistica or Cabalistic Tree, showing the ten sefirot.

The Judaic tradition of the Kabbalah is rich and complex, and while it should be understood primarily as a form of mysticism through which an individual seeks to know God, throughout its long history it has also embraced magical elements as well. After all, understanding the structure of the universe is the first step in learning how to manipulate it. Kabbalistic magic already existed in the Judaic tradition when it attracted the interest of Christian scholars, and it did not take long for the Christianized cabalistic tradition to incorporate magical practices as well.

Given the hostility with which many premodern Europeans viewed Jewish culture, it might seem surprising that a Jewish mystical tradition would interest Christian philosophers at all. If we remember the European fascination with both prisca sapientia and prisca theologia, however, it starts to make a little more sense. It was widely acknowledged that Judaic theology and mysticism predated the rise of Christianity, leading some to believe that Judaism contained truths that had since been lost or corrupted. Some of the earliest European interest in a Christian cabala originated with the conversos, individuals who had converted from Judaism to Christianity in Spain and Portugal in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Many conversos sought to reconcile these two faiths or, in some cases, to find an effective way to convert others from Judaism to Christianity. As they sought a common ground between the two, they inspired some Christians to do the same thing.

Prominent among these Christians was Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, the protégé of Ficino, who is generally acknowledged today as the first Christian to disseminate the cabala to a wide audience. He became fascinated with both the Kabbalah and hermeticism toward the end of the fifteenth century and believed that the revelation of mysteries was possible only by combining and synthesizing the various traditions of distant antiquity into a single philosophy that included Aristotelianism, Neoplatonism, hermeticism, and the Kabbalah. He presented this unorthodox vision in his Nine Hundred Theses, a series of arguments that brought together natural philosophy, theology, and several different occult traditions. He intended to hold a public forum in Rome where scholars from across Europe would debate his ideas, but in 1487 Pope Innocent VIII (1432–92) intervened and ultimately declared some of Pico’s ideas to be heretical, meaning that they directly contradicted Church doctrines and teachings. Pico’s work became the first printed book to be banned by the Church, after which most copies were confiscated and destroyed.

Those who came after Pico, such as Johann Reuchlin (1455–1522), Francesco Giorgi (1467–1540), and Giordano Bruno (1548–1600), continued to explore the connections between the mystical Kabbalist tradition and Christian theology. Reuchlin’s De Arte Cabbalistica, published in 1517, became especially influential in the study of the Christian cabala. Reuchlin argued that the cabala offered one of the best ways of demonstrating the truth of Christianity as well as the means to connect the study of nature with the veneration of God. Guillaume Postel (1510–81), who came of age after Reuchlin’s death, used the cabala to define and understand the many connections or correspondences that he thought existed between different things. Like the hermeticist Fludd and his fellow Jesuit Kircher, Postel conceived of the universe as a vast tapestry in which fundamental truths about nature could be revealed by tracing the hidden links between disparate objects and phenomena.

Ultimately, interest in the cabala stretched into the early decades of the eighteenth century, though its popularity among the educated classes had decreased significantly by that point. Since then, both the Judaic Kabbalah and the Christianized cabala have experienced periodic revivals in the West, often coinciding with broader revivals of interest in mystical and esoteric ideas. The same is true for hermeticism, with which the cabala shares many important similarities. Both assumed prominence as part of Renaissance humanism and its recovery of ancient ideas. Both were esoteric traditions that embraced the discovery and revelation of mysteries, and both had strong connections to prisca sapientia and prisca theologia. Advocates and proponents of these traditions saw them as a means of reforming or correcting religion by returning it to its most ancient roots, as well as a means of gaining knowledge about the natural world. Both hermeticism and the cabala were unmistakably religious or spiritual endeavors, but many of their followers also believed that there was a practical dimension to the knowledge they revealed – they each promised the ability to manipulate the world in certain ways, which we should understand as the hallmark of a magical tradition. At the very least, there was widespread agreement among philosophers and scholars that the more one understood the foundations of the universe, the more easily one could manipulate them, and that understanding was central to both hermeticism and the cabala.

The Learned Magician

As interest in learned magic spread across Europe, so too did anxieties and fears about what its practitioners might accomplish. Consider, for example, two different but overlapping depictions of the learned magician or magus. One is a fictional character named Faustus or Faust, the protagonist of different stories that circulated for centuries before reaching a much wider audience in a popular play written by the English playwright Christopher Marlowe (1564–93). The other is a real person who not only lived at the same time as Marlowe, but whose life may have influenced Marlowe’s depiction of Faustus: the English astrologer, mathematician, and philosopher John Dee (1527–1608). Between them, Faustus and Dee reveal why practitioners of learned magic were seen by some as frightening personifications of hubris and folly.

At its most basic, the story of Faustus demonstrated for European audiences the moral and physical dangers of learned magic. Its origins are unclear; there are cautionary tales and stories about Faustus that stretch back to the Middle Ages, many of them first circulating in what is now Germany. Some of those stories later became associated with tales of an unnamed traveling magician who supposedly lived around the beginning of the sixteenth century and who blasphemously claimed to be able to replicate the miracles of Christ through the use of magic. It is difficult to know if any of these tales were true, however, meaning that Faustus may have been a real person, a myth constructed from innuendo and imagination, or both. His story was popularized for English audiences by the playwright Christopher Marlowe, a contemporary of Shakespeare, in his The Tragicall History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus. First performed sometime around 1590, Marlowe’s play helped to cement the reputation of Faustus as a learned magician who consorted with dark forces and ultimately met an untimely and gruesome end (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5 Title page from The Tragicall History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus by Christopher Marlowe, 1636.

In the play, Faustus is a wise and learned man who, through many years of patient work, had uncovered knowledge about almost everything in the world. But he still hungers for more, and so he turns to a disreputable magician for help in summoning a demon. The idea that demons or the Devil himself could be asked to aid the desperate or the foolish has a long history, and the next chapter, which examines European witchcraft, will have much more to say on this subject. In the context of the Faustus myth, however, the summoning of a demon played into a common belief concerning magic and those who practiced it – namely, that they worked with dark forces and powers in pursuit of power and mastery over the world. In Marlowe’s telling, however, Faustus summons the demon Mephistophilis and strikes a bargain with Lucifer (the Devil) not because he is inherently corrupt or evil but because he is curious. He desires knowledge rather than power, at least at first. He asks for twenty-four years of life, during which he will be able to work magic; in return, he promises his soul to Lucifer. But Faustus does not receive the knowledge he wanted so desperately. The demon Mephistophilis, though supposedly his servant, refuses to answer his questions, and Faustus ultimately abuses his magical knowledge to perform cheap tricks and pranks for the next twenty-four years. Finally, as his contract with Lucifer comes due, Faustus realizes his mistake and tries to repent, but it is too late. The play ends with Faustus being dragged from the stage and into Hell, screaming to God for help.

Marlowe’s play was a big hit with Elizabethan audiences. There were rumors that real devils and demons appeared on stage during the performances, drawn there by the story of the infamous Faustus, and that some members of the audience were driven mad when they saw these supernatural apparitions. Ultimately, Marlowe’s retelling of the Faustus myth was concerned more with the dangers of pride and arrogance rather than those posed by learned magic, but it still provides us with some insight into how early modern people thought about magical practitioners. Among philosophers and naturalists, hermeticism, cabalism, and other forms of esoteric knowledge were valued because they offered the possibility of understanding the universe in new and powerful ways. They represented both the wisdom of antiquity and the promise of new innovations to come. But to others – members of the clergy as well as ordinary people – learned magic was dangerous, an attitude that harkens back to the medieval belief that all magic was inherently demonic. The clever wiles of demons and devils too easily could ensnare the careless or arrogant magician, and this was a danger not just to the magician himself but also to those around him. For many, magic was a threat to social order and public welfare, and it was this same threat that drove the persecution of both the learned magician and the uneducated witch.

This idea of persecution or suspicion is a key part of the story of John Dee (Figure 1.6). He was already a well-known, even infamous figure by the time Marlowe wrote his play, and it is possible that both Marlowe and his audience drew connections between the fictional character Faustus and the real-life magus Dee. The beliefs of the latter demonstrate not just the powerful attractions of the occult and esoteric knowledge we have examined in this chapter, but also the ways in which this knowledge was intertwined closely with religion and natural philosophy in this period. Dee was heavily influenced by hermeticism and by the Neoplatonic philosophy of Marsilio Ficino, and it is clear that he was also well versed in the subject of the cabala. Like Ficino and many others, Dee saw both philosophy and magic as necessary to draw back the metaphorical curtain and apprehend the truths that lay behind the physical world.

Figure 1.6 Portrait of John Dee, c. 1580.

Dee rightly should be understood first and foremost as a mathematician, though in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the concept of “mathematics” was very broad. In Dee’s case, his mathematical expertise encompassed astronomy, astrology, navigation, and mechanics, all of which we today would consider examples of applied mathematics. But Dee also believed that mathematics was the key to more esoteric knowledge as well. He claimed that numbers were the key to understanding the universe. In this, he was not very different from contemporary thinkers like Galileo Galilei, who we will encounter in Chapter 4. Galileo was also a highly skilled mathematician who argued that mathematics was the language with which God had created the world. In most other respects, though, Dee and Galileo were very different people; for example, Galileo had no interest in hermeticism or the occult philosophies that so fascinated Dee.

Dee’s skill with mechanics led him to build some dazzling special effects for a play produced while he was at university, and the results were so convincing and strange that he was accused by some of trafficking with dark powers. This led to his being widely regarded as a magician during his lifetime, a label that he occasionally resented. He became an unofficial advisor to the young princess Elizabeth, and when she ascended to the English throne in 1558, the date of her coronation was determined by Dee’s astrological calculations. Later in life she appointed him her court astrologer.

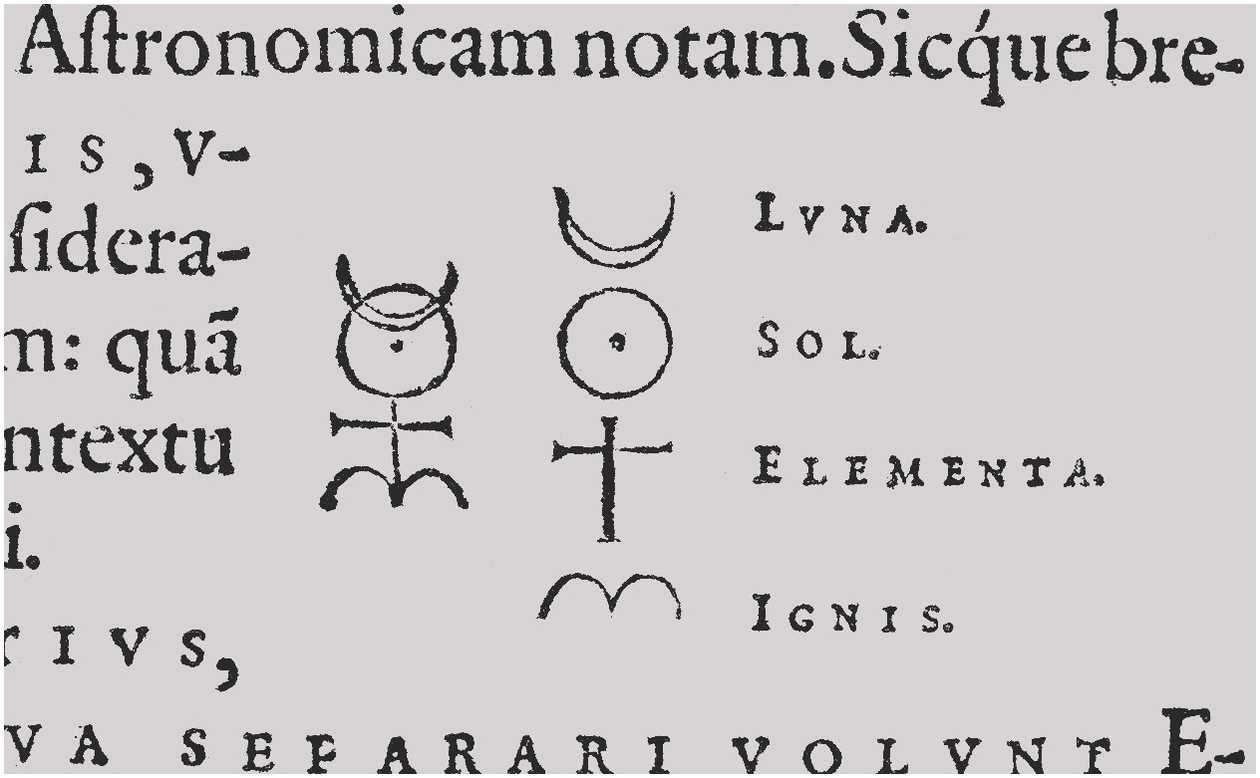

In 1564 Dee published the Monas Hieroglyphica, a work with strong hermetic as well as cabalistic influences. The Hieroglyphic Monad is a symbol that Dee invented which expressed, for him, the unity of the cosmos and its elements (Figure 1.7). Its exact meaning remains a mystery, however, because the commentary that Dee published in the Monas Hieroglyphica is so obscure as to be impossible to decipher. Dee’s ideas had a significant influence on others, however – the Monad appeared in numerous works from this period, including an infamous treatise that claimed to describe a hidden esoteric community known as the Rosicrucians, or the Fraternity of the Rosy Cross. Manifestoes laying out the existence and purpose of the Rosicrucians appeared across Europe in the first decades of the seventeenth century, with one of the earliest being the Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz, first published in 1616. It was no accident that the Chymical Wedding featured a prominent image of Dee’s Hieroglyphic Monad; the manifesto and its ideas both emerged from the same tradition of esoteric knowledge in which Dee himself was immersed.

Figure 1.7 Dee’s Hieroglyphic Monad from his Monas Hieroglyphica, 1564.

The Rosicrucian manifestos presented the recovery of ancient esoteric wisdom as the key to humanity’s spiritual “reformation,” and together they demonstrate how traditions such as hermeticism and cabalism evolved during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, long after Ficino’s original translation of the Corpus Hermeticum. There is little evidence that the Rosicrucians actually existed, however; their manifestos may have been part of a grand hoax, or perhaps the idealistic imaginings of a single person. Even if this shadowy society did not exist, however, the philosophy laid out in the Chymical Wedding and other works described a quest for esoteric and occult knowledge inspired directly by the hermetic and cabalistic traditions and personified in practitioners like Dee.

Though Dee was widely known and respected both in England and on the Continent, by the 1580s he had become dissatisfied with his waning influence in the court of Elizabeth I. He began to pursue new directions for acquiring esoteric knowledge, eventually devoting considerable efforts to “scrying” – using reflective surfaces to see and communicate with other beings – which eventually evolved into supposed conversations with angels. In fact, this development was not a huge deviation from his existing interests. For Dee, as for many others, hermeticism and cabalism were both ways to understand the mind of God, and in pursuit of that goal, talking with angels was little more than a shortcut. After numerous failed attempts, Dee came to believe that he himself did not possess the ability to communicate with angels or other spirits and that he would need to use an intermediary, a scryer who could gaze into a polished mirror of obsidian or a crystal ball and both see and hear the voices of the angels. After some unsuccessful attempts with several different scryers, in 1582 Dee met Edward Kelley (1555–97), a rather mysterious figure who would eventually acquire as colorful a reputation as Dee himself. Some accounts claim that Kelley was a convicted forger who had had part of his ears removed as punishment, and historians are divided as to whether Kelley’s work with Dee was sincere or an elaborate exercise in fraud and deception.

It was through Kelley that the angels spoke to Dee for many years. They dictated entire books, written in an angelic language that only Kelley could understand. Dee was seeking a remedy for the religious divisions that had fractured Christendom following the Protestant Reformation, and he turned to the angels for a pure and ancient theology – the prisca theologia – that he believed could unify the warring factions of Christianity. For Dee, this was first and foremost a religious endeavor; occultism and esoteric philosophies like hermeticism were merely the means of uncovering hidden religious and theological truths.

Dee and Kelley, with their wives, traveled to the Continent and met with both the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II (1552–1612) and Stefan Báthory (1533–86), king of Poland. Rudolph in particular was fascinated with occultism and alchemy, and Dee and Kelley had hopes of receiving his patronage, though this never materialized. They spent several years in central Europe until, in 1587, Kelley passed along a surprising message from the angels: They wanted Dee and Kelley to share all of their possessions, including their wives. Dee was troubled by this revelation and broke off his relationship with Kelley – but not before the two men swapped wives for an evening. Dee returned to England while Kelley remained in Prague and worked as an alchemist in the employ of Rudolph II. Kelley promised Rudolph that he could transmute base metals into gold, and the Emperor was so impressed that he knighted Kelley in 1590, only to imprison him the following year. The rest of Kelley’s life was a mixture of opulence and hardship. He was imprisoned repeatedly by Rudolph for failing to produce the promised gold, and it is generally believed that he died after sustaining serious injuries while trying to escape from prison.

As for John Dee, he returned to England to find that his vast library had been partially destroyed by an angry mob fearful of Dee’s reputation as a sorcerer. This exemplifies the fear and anxiety that so often accompanied even the suspicion of magic in this period. Dee was not the first to suffer consequences for his interest in the esoteric and occult arts, and he certainly was not the last. The fate of his library and of Dee himself – he died in poverty at the age of 82 – shows us that the learned pursuit of magic could be a dangerous thing.