Employees seek to remain with organizations that offer career growth opportunities (Weng, McElroy, Morrow, & Liu, Reference Weng, McElroy, Morrow and Liu2010). However, the traditional perspective that knowledge and hard work inevitably lead to career growth may not serve as the only explanation (Blickle, Schneider, Liu, & Ferris, Reference Blickle, Schneider, Liu and Ferris2011), as recent empirical evidence has revealed other potential factors, such as political savvy and networking (Cullen, Gerbasi, & Chrobot-Mason, Reference Cullen, Gerbasi and Chrobot-Mason2018; Ren & Chadee, Reference Ren and Chadee2017; Spurk, Kauffeld, Barthauer, & Heinemann, Reference Spurk, Kauffeld, Barthauer and Heinemann2015). For instance, employees high in political skill tend to view connections formed with other organizational members as opportunities to capitalize on (McAllister, Ellen, & Ferris, Reference McAllister, Ellen and Ferris2018). Subsequently, they proactively engage in building relationships with others, especially their supervisors and other higher-ups, as these connections allow for greater access to valuable resources, such as job information, professional advice, and emotional support, thereby equipping individuals with capabilities for growth (Wei, Liu, Chen, & Wu, Reference Wei, Liu, Chen and Wu2010). Indeed, politically skilled individuals possess a distinct interpersonal capability that enables them to present their behaviors in ways that inspire trust and goodwill, leading to favorable interpersonal relationships (Epitropaki et al., Reference Epitropaki, Kapoutsis, Ellen, Ferris, Drivas and Ntotsi2016). Drawing upon social resources theory (Lin, Ensel, & Vaughn, Reference Lin, Ensel and Vaughn1981), this study considers political skill (Ferris et al., Reference Ferris, Treadway, Perrewé, Brouer, Douglas and Lux2007) as an important interpersonal competency that employees can use to enhance their career growth potential, which is determined by a supervisor's assessment of the employee's readiness to achieve career growth opportunities (e.g., job enrichment, promotions, training and development, etc.). Through relationship building, politically skilled employees are able to form connections with their supervisors who can grant them access to the necessary resources for career advancement. Political skill consistently proved to be a significant predictor of career-related benefits, including perceived employability, promotability ratings, and actual promotions (Blickle et al., Reference Blickle, Schneider, Liu and Ferris2011; Chiesa, Van der Heijden, Mazzetti, Mariani, & Guglielmi, Reference Chiesa, Van der Heijden, Mazzetti, Mariani and Guglielmi2020; Todd, Harris, Harris, & Wheeler, Reference Todd, Harris, Harris and Wheeler2009).

This study is conducted in the context of Japanese careers, which have experienced drastic changes since the collapse of the ‘bubble’ economy in the late 1990s. Typical Japanese companies highly emphasize lifelong employment in exchange for employees' lifetime commitment (Dore, Reference Dore1973). However, due to current business environment dynamics, organizations can no longer guarantee such support for their workers. Under these new circumstances, many employees in Japan have since realized that they must take control of and manage their own careers (Kuroda & Yamamoto, Reference Kuroda and Yamamoto2005; Taniguchi, Kato, & Suzuki, Reference Taniguchi, Kato and Suzuki2006). Similarly, we recognize that employees are not passive recipients of their work environments but rather active individuals who can improve their work circumstances and thus, exert agency over their career course (King, Reference King2004). Specifically, we suggest that employees can utilize their interpersonal competency, notably political skill, to navigate work, and place themselves in stronger positions to attain career growth. Further informed by the Japanese work culture, which can be generally regarded as highly collectivistic and showing high uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1984), we emphasize relationship building as an instrumental factor in achieving career growth. In a highly collectivistic work culture, people participate in informal groups and engage in interpersonal relationships. In a high-uncertainty avoidance culture, people tend to feel uncomfortable within ambiguous situations and seek to find ways in which they can become more informed about their surroundings (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001). In this regard, it is reasonable to see employees building relationships with more senior staff, such as their supervisors, as they can help provide important information about an organization's context (Bozionelos, Reference Bozionelos2006). Due to their adaptable and delicate interpersonal capabilities (Ferris et al., Reference Ferris, Treadway, Perrewé, Brouer, Douglas and Lux2007), employees high in political skill can effectively form strong connections with their supervisors, who serve as gatekeepers to information and resources, some of which are essential in promoting their career growth potential (King, Reference King2004; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Liu, Chen and Wu2010; Wei, Chiang, & Wu, Reference Wei, Chiang and Wu2012).

Given that the key skillset and career context of interest are within the interpersonal domain, we consider two types of resources that employees can interpersonally source from their supervisors. First, supervisor-focused expressive network resources consist of strong interpersonal relationships that employees form with their supervisors, which further provide friendship, emotional support, confirmation, and feedback on work-related issues (Fombrun, Reference Fombrun1982; Krackhardt, Reference Krackhardt, Eccles and Nohria1992). Our argument is that such emotionally supportive relationships are essential in promoting one's career growth in a highly collectivistic work culture such as Japan, as they emphasize relationship building and informal connections. Second, supervisor developmental feedback contains information related to in-role expectations, extra-role expectations and cultural norms, all of which aim toward the long-term development of employees (George & Zhou, Reference George and Zhou2007; Li, Harris, Boswell, & Xie, Reference Li, Harris, Boswell and Xie2011). Such information is highly valuable in a high-uncertainty avoidance work culture such as Japan, as it helps reduce uncertainty that employees may have toward organizational context. Importantly, due to the future orientation of developmental feedback (Zhou, Reference Zhou2003), we argue that this information is important in achieving longer-term career outcomes, such as career growth.

While many studies have endeavored to examine the benefits of overall social resources (Bozionelos, Reference Bozionelos2003; Wolff & Moser, Reference Wolff and Moser2009), there are still mixed results concerning their instrumentality in achieving career objectives (Bozionelos & Wang, Reference Bozionelos and Wang2006; Seibert, Kraimer, & Liden, Reference Seibert, Kraimer and Liden2001). Therefore, the mere existence of resources may not sufficiently explicate the link between political skill and career growth potential. Our argument is that individuals can differ in the extent to which they will combine, utilize, and leverage the social resources obtained from having exercised their political skill to increase their chances for career growth. Specifically, we suggest that employees can place themselves in even stronger positions if they take advantage of the attained expressive network resources and developmental feedback by executing strategic, goal-directed influence tactics, such as ingratiation, which is described as an attempt to enhance one's interpersonal attractiveness and gain favors from another person (Kumar & Beyerlein, Reference Kumar and Beyerlein1991). Given the interpersonal focus of ingratiation (Liden & Mitchell, Reference Liden and Mitchell1988), this strategy is essential in enabling employees to navigate through the informal connections that they have formed with their supervisors, further allowing them to tailor the use of their resources to lead to career growth. Strong empirical evidence supports the instrumental role of ingratiation in attaining career-related benefits (Sibunruang, Garcia, & Tolentino, Reference Sibunruang, Garcia and Tolentino2016; Wu, Kwan, Wei, & Liu, Reference Wu, Kwan, Wei and Liu2013).

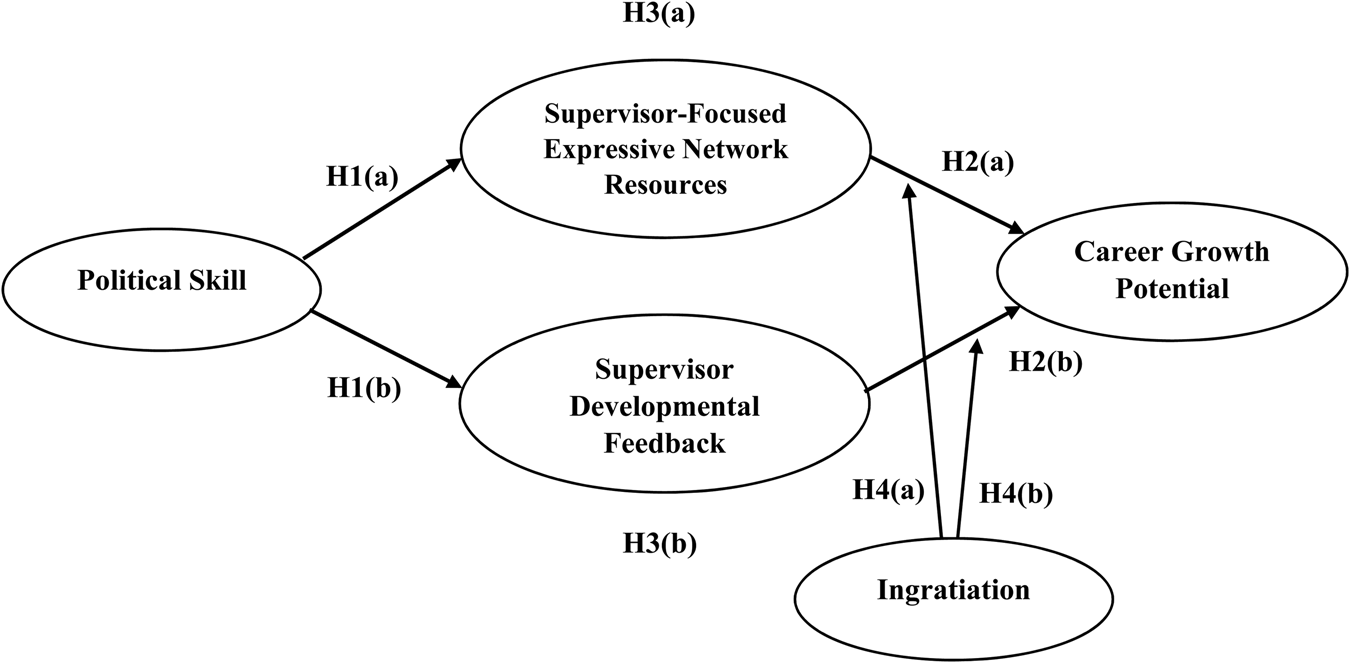

Ultimately, this study aims to address ‘why do some employees experience more successful career growth?’ We do so by using social resources theory (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Ensel and Vaughn1981) as an overarching theoretical perspective to provide an integrated understanding of how interpersonal competency (i.e., political skill), social resources (i.e., expressive network resources and developmental feedback from supervisors), and interpersonal influence behaviors (i.e., ingratiation) merge to promote employee career growth potential (see Figure 1). In doing so, we contribute to the career growth literature in the following ways. First, our proposed research model is informed by the current career circumstances facing Japanese employees and some of the dominant features of their cultural work context. Weng & Zhu (Reference Weng and Zhu2020) noted in their review paper that research on career growth should take a more context-specific approach, because the notion of careers involves an interplay between individual employees, organizations, and society. Therefore, career growth is inevitably influenced by the surrounding contexts and situations in which it occurs. Second, this study provides insights into some of the unexplored mechanisms that may unpack the benefits of political skill on career growth. For instance, in promoting career interests, past research has largely emphasized the significance of instrumental network resources (e.g., Blommaert, Meuleman, Leenheer, & Butkēviča, Reference Blommaert, Meuleman, Leenheer and Butkēviča2020; Bozionelos, Reference Bozionelos2003; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Seibert, Sargent, Kraimer, & Kiazad, Reference Seibert, Sargent, Kraimer and Kiazad2017), which enable exposure to top management as well as access to job-related information and professional advice, while little is known about the potential of expressive network resources. Our argument is that expressive resources provide psychosocial support via a close friendship, which not only fosters trust but also facilitates the exchange of valued resources (Brass, Reference Brass1984). In fact, trust is a key component of sharing and exchanging benefits among individuals in a relationship (Bradach & Eccles, Reference Bradach and Eccles1989). Finally, we recognize supervisor developmental feedback as another critical aspect in advancing one's career. While research has thus far determined the behavioral outcomes of developmental feedback, such as task performance, helping behaviors, and creativity (Li et al., Reference Li, Harris, Boswell and Xie2011; Zhou, Reference Zhou2003), the future-oriented nature of this feedback should be particularly essential in directing employees’ attention and motivation toward long-term outcomes, such as career growth. In sum, our study aims to address this limited attention on the instrumentality of both expressive network resources and developmental feedback from supervisors in achieving career objectives.

Figure 1. The proposed research model.

Theory and development of hypotheses

Popular advice for getting ahead in one's career never fails to mention relationship building and networking, especially with important people who can bring them closer to their career objectives (Blickle et al., Reference Blickle, Kramer, Schneider, Meurs, Ferris, Mierke and Momm2011; Perrewe & Nelson, Reference Perrewe and Nelson2004; Todd et al., Reference Todd, Harris, Harris and Wheeler2009). For this reason, some employees are highly active in forming connections with more senior staff, such as their supervisors, to gain access to information and win social support in the organization (Cullen et al., Reference Cullen, Gerbasi and Chrobot-Mason2018; Yang, Liu, Wang, & Zhang, Reference Yang, Liu, Wang and Zhang2020). According to social resources theory (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Ensel and Vaughn1981), access to social resources is instrumental to achieving personal objectives. More specifically, the theory encompasses two key components, notably, (a) social relations and (b) resources embedded in these social relations. First, the theory advocates the relevance of connecting with those at higher levels of the management hierarchy. Due to their position, these people generally have greater access to and control over information, resources, and rewards. Following this line of argument, we argue that employees high in political skill are better able to form valuable connections with their immediate supervisors, thereby allowing them greater access to the resources needed to advance in their career (McAllister et al., Reference McAllister, Ellen and Ferris2018; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Liu, Chen and Wu2010, Reference Wei, Chiang and Wu2012). In addition to relationship building, the theory further focuses on the nature of resources embedded in these social networks. In other words, it is also important to consider the type of resources required for individuals to reach their personal career objectives (Seibert et al., Reference Seibert, Kraimer and Liden2001). In this study, we consider the strategic functions that supervisor-focused expressive network resources and supervisor developmental feedback may serve in enabling politically skilled employees to enhance their career growth potential.

Political skill and the acquisition of social resources

Resource acquisition is the result of relationship building and informal connections formed among individuals in a particular social network (Seibert et al., Reference Seibert, Kraimer and Liden2001). Guided by social resources theory (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Ensel and Vaughn1981), ‘social resources are embedded in the positions of contacts an individual reaches through his social network’ (p. 395). The theory specifically highlights connections formed with those at higher levels of the management structure, such as supervisors, managers, and other higher-ups. Due to their positional power, these people have more control over the distribution of many valuable resources (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Ensel and Vaughn1981). When individuals are well positioned in these networks, their ability to garner, utilize, and leverage the available resources figures prominently (Wei et al., Reference Wei, Liu, Chen and Wu2010, Reference Wei, Chiang and Wu2012). Therefore, one's ability to engage in interpersonal relationships is important in acquiring social resources, such as expressive network resources and developmental feedback (Fang, Chi, Chen, & Baron, Reference Fang, Chi, Chen and Baron2015). For instance, employees who possess political skill have an astute understanding of their social environment and know how to use this understanding to build relationships with others (Ferris et al., Reference Ferris, Treadway, Kolodinsky, Hochwarter, Kacmar, Douglas and Frink2005, Reference Ferris, Treadway, Perrewé, Brouer, Douglas and Lux2007). Due to positive and successful experiences in past encounters, research has revealed that politically skilled employees derive a greater sense of personal security and self-confidence that they can successfully gain positive responses from engaging in interpersonal interactions with others (Munyon, Summers, Thompson, & Ferris, Reference Munyon, Summers, Thompson and Ferris2015). As a result, employees high in political skill actively build social networks at work, as they view relationships as opportunities that they can exploit for future gain (McAllister et al., Reference McAllister, Ellen and Ferris2018; Perrewé, Ferris, Frink, & Anthony, Reference Perrewé, Ferris, Frink and Anthony2000).

Individuals who are high in political skill display four important characteristics. First, due to their quality of being socially astute, politically skilled employees have an accurate understanding of other people's motivations and behaviors, which helps them identify the correct way to interact with others (Ferris et al., Reference Ferris, Treadway, Kolodinsky, Hochwarter, Kacmar, Douglas and Frink2005, Reference Ferris, Treadway, Perrewé, Brouer, Douglas and Lux2007). Furthermore, due to their networking ability, politically skilled employees are adept at identifying relevant contacts who could help them create opportunities, such as their supervisors, and are also effective in building social networks as well as positioning themselves within these networks (Ferris et al., Reference Ferris, Treadway, Perrewé, Brouer, Douglas and Lux2007; McAllister et al., Reference McAllister, Ellen and Ferris2018). Networking is a dyadic interpersonal process that involves generating social capital, goodwill, and trust between members within a social network (Porter & Woo, Reference Porter and Woo2015). Political skill also consists of specific action-oriented capabilities. For instance, interpersonal influence represents one's ability to adapt his or her behavior to different social contexts, which allows employees to make the right impression in front of their supervisors and build a good rapport. Finally, apparent sincerity represents one's ability to behave in a manner that appears authentic, genuine, and sincere, which can help an employee hide their ulterior motives and instead instill trust in their supervisors (Ferris et al., Reference Ferris, Treadway, Kolodinsky, Hochwarter, Kacmar, Douglas and Frink2005, Reference Ferris, Treadway, Perrewé, Brouer, Douglas and Lux2007). Trust is a critical factor that facilitates the exchange of valuable resources among individuals (Bradach & Eccles, Reference Bradach and Eccles1989).

Therefore, politically skilled employees are well equipped with specific interpersonal abilities that enable them to develop favorable interpersonal relationships with their supervisors and, as a result, gain access to social resources, including supervisor-focused expressive network resources as well as supervisor developmental feedback.

Hypothesis 1: Political skill is positively associated with (a) supervisor-focused expressive network resources and (b) supervisor developmental feedback.

Social resources and career growth potential

The social resources acquired from having utilized political skill are instrumental in achieving career growth. Further informed by social resources theory (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Ensel and Vaughn1981), once relationships with key gatekeepers (e.g., immediate supervisors) who control the distribution of certain resources have been formed, the extent to which individuals will successfully achieve their career objectives also depends on the nature of the resources embedded in these social ties. Similarly, we assert that supervisor-focused expressive network resources and supervisor developmental feedback are essential in promoting employee career growth potential, especially when accounting for the dominant features of the Japanese work culture (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1984). First, Japanese work culture is regarded as highly collectivistic; people within the culture strongly value group membership and group harmony (Leung, Au, Fernández-Dols, & Iwawaki, Reference Leung, Au, Fernández-Dols and Iwawaki1992). For this reason, participation in informal groups and engagement in interpersonal relationships (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001) are deemed appropriate in such a cultural setting, and these actions are more likely to be an effective way for employees to work toward their career growth (Bozionelos, Reference Bozionelos2006). Indeed, expressive network resources denote strong interpersonal relationships formed among organizational members, which further provide emotional support, confirmation, feedback on work-related issues, and certain types of information (Ibarra, Reference Ibarra1993; Krackhardt, Reference Krackhardt, Eccles and Nohria1992). Japanese work culture can be further described as having high uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1984). In other words, people tend to feel uncomfortable in uncertain situations and will seek to minimize such ambiguity in their surroundings. Hence, it is reasonable to expect that employees in this cultural setting are inclined to seek relationships with more senior members, such as their supervisors, as such relationships could help reduce uncertainty by providing important information about the organization's environment (Bozionelos, Reference Bozionelos2006). This information can be disseminated in a form of supervisor developmental feedback, which reflects the extent to which supervisors provide helpful and valuable information that enables employees to improve their work and broader aspects of their work life (Li et al., Reference Li, Harris, Boswell and Xie2011).

Supervisor-focused expressive network resources denote closely tied connections formed between employees and supervisors (Bozionelos, Reference Bozionelos2006). Such favorable interpersonal relationships are likely to offer more fine-grained information that is essential in achieving personal objectives, facilitate rapid feedback exchange concerning work-related issues, and allow access to a greater amount of support. These outcomes are largely due to mutual trust shared among closely connected members (Bradach & Eccles, Reference Bradach and Eccles1989). Subsequently, timely access to as well as the quantity and quality of the benefits obtained from supervisor-focused expressive resources should help enhance individuals' work performance and effectiveness, making them ready for career growth (Seibert et al., Reference Seibert, Kraimer and Liden2001). Indeed, the extent to which supervisors and managers allocate career growth opportunities depends on their assessment of an employee's performance and competence (Liu, Liu, & Wu, Reference Liu, Liu and Wu2010). Furthermore, considering the affective perspective, when supervisors assess their employees' capabilities and potential for career growth, their assessment can be easily influenced by their subjective feelings developed toward a stimulus object, notably a focal employee (Feldman, Reference Feldman1981; Ferris & Judge, Reference Ferris and Judge1991). Specifically, supervisors are more likely to favorably rate employees with whom they share close connections.

Supervisor developmental feedback can be described as ‘the extent to which supervisors provide their employees with helpful or valuable information that enables the employees to learn, develop and make improvements on the job’ (Zhou, Reference Zhou2003, p. 415). This type of feedback should equip employees for career growth for three major reasons. First, supervisor developmental feedback contains information that communicates relational roles, cultural norms, and extra-role expectations (George & Zhou, Reference George and Zhou2007; Zhou, Reference Zhou2003), which enables employees to become well informed of their surrounding work environments. As shown in Li et al. (Reference Li, Harris, Boswell and Xie2011) study, new employees who received more developmental feedback from their coworkers and supervisors managed to transition into the new workplace more easily and subsequently exhibited higher performance levels during the socialization period compared to those who received less developmental feedback. Following these lines of argument, we argue that employees require such information to navigate work, thrive in their organizations, and pave their way toward career growth. Second, developmental feedback contains behaviorally relevant information that aims to improve one's performance at work (Zhou, Reference Zhou2003). Hence, the provided feedback is highly specific in terms of directions and specific actions that employees can take to make overall work improvements. Accordingly, supervisor developmental feedback is reported as a significant predictor of important work outcomes, such as task performance and creative performance (Li et al., Reference Li, Harris, Boswell and Xie2011; Zhou, Reference Zhou2003). The more positive a supervisor's assessment of an employee's performance potential, the greater the allocation of career growth opportunities (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Liu and Wu2010). Importantly, developmental feedback has a future orientation, which will likely direct employees' attention and motivation toward achieving long-term goals, such as career growth. While research on the impact of supervisor developmental feedback on long-term career outcomes is rather scant, there is empirical support for how developmental feedback may promote a longer-term outlook for employees toward their employer (e.g., higher organizational commitment and lower turnover intention; Joo & Park, Reference Joo and Park2010).

Building on the aforementioned arguments, we predict that the greater the access employees have to social resources, notably expressive network resources and developmental feedback from supervisors, the higher their chances and potential for attaining career growth.

Hypothesis 2(a): Supervisor-focused expressive network resources are positively associated with career growth potential.

Hypothesis 2(b): Supervisor developmental feedback is positively associated with career growth potential.

In sum, social resources theory (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Ensel and Vaughn1981) posits two key factors that lead to the achievement of career objectives, including relationship building and resources embedded in the relationship developed. Guided by this theoretical perspective, our argument is that employees high in political skill are in a strong position to obtain expressive network resources and developmental feedback granted by their supervisors. Through active networking and their ability to be convincing, these employees are able to form favorable relationships with their supervisors and, therefore, are better able to secure the support, feedback, and information needed for career growth (Wei et al., Reference Wei, Liu, Chen and Wu2010, Reference Wei, Chiang and Wu2012). Combining the above two predictions (i.e., Hypotheses 1 and 2), we expect that supervisor-focused expressive network resources and supervisor developmental feedback will account for mediating mechanisms through which politically skilled employees can enhance their career growth potential.

Hypothesis 3(a): Supervisor-focused expressive network resources mediate the relationship between political skill and career growth potential.

Hypothesis 3(b): Supervisor developmental feedback mediates the relationship between political skill and career growth potential.

The moderating role of ingratiation

While expressive network resources and developmental feedback provided by supervisors can potentially promote employee career growth potential, these resources can be further leveraged toward optimizing an individual's chances for career growth. For instance, employees can exercise goal-directed, strategic influence behaviors, such as ingratiation, toward their immediate supervisors. Ingratiation is a set of interpersonal behaviors that attempt to increase one's interpersonal attractiveness and ultimately gain favors from another individual (Kumar & Beyerlein, Reference Kumar and Beyerlein1991; Westphal & Stern, Reference Westphal and Stern2007). Examples of ingratiation include giving compliments, showing agreement with another person's opinions, and doing favors for someone (Higgins & Judge, Reference Higgins and Judge2004; Kumar & Beyerlein, Reference Kumar and Beyerlein1991). Overall, ingratiation has been demonstrated to result in numerous positive outcomes, including positive performance ratings, career success, and increased chances for board appointments (Aryee, Wyatt, & Stone, Reference Aryee, Wyatt and Stone1996; Sibunruang et al., Reference Sibunruang, Garcia and Tolentino2016; Westphal & Shani, Reference Westphal and Shani2016).

This strategy plays an important role in three important ways. First, due to the interpersonal focus of ingratiation (Liden & Mitchell, Reference Liden and Mitchell1988), this strategy is essential in enabling employees to maintain the strong connections they have formed with their supervisors. Both supervisor-focused expressive network resources and supervisor developmental feedback can be gained from having developed favorable relationships with supervisors (Bozionelos, Reference Bozionelos2006). Thus, to maintain these relationships and access to the necessary resources for career growth, interpersonal behaviors such as ingratiation are useful. Second, by exercising ingratiation toward their supervisors, employees can elicit positive affect in their supervisors and subsequently instill trust in them (Heider, Reference Heider1958). The trust and goodwill generated make it easier for employees to navigate the informal connections formed with their supervisors. In doing so, they can gain even more in-depth insight into their surrounding work environment, including its nature, boundaries and standards, which better informs them how to use the obtained resources to make their way toward career growth. Finally, ingratiation is a goal-directed behavior. One motivation behind exercising ingratiation is achieving personal career goals (Judge & Bretz, Reference Judge and Bretz1994). With this goal in focus, employees can direct their ingratiatory effort and behaviors toward achieving career growth when coupled with using expressive network resources and developmental feedback.

Along these lines of argument, we expect that employees who ingratiate their supervisors more frequently will be better able to maintain their access to the social resources (i.e., supervisor-focused expressive network resources and supervisor developmental feedback) obtained from having utilized their political skill, and further leverage them toward maximizing their chances for career growth. By contrast, if employees exercise ingratiation less frequently, the social resources obtained from their political savvy will be less leveraged toward enhancing their career growth potential. Importantly, while political skill enables access to social resources (i.e., political skill as a predictor), ingratiation enables maintaining and utilizing these resources to achieve career growth (i.e., ingratiation as a second-stage boundary condition).

Hypothesis 4(a): At the second-stage moderation, the mediating relationship between political skill, supervisor-focused expressive network resources, and career growth potential becomes stronger at high ingratiation levels as opposed to low ingratiation levels.

Hypothesis 4(b): At the second-stage moderation, the mediating relationship between political skill, supervisor developmental feedback, and career growth potential becomes stronger at high ingratiation levels, as opposed to low ingratiation levels.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Our research included 900 full-time employees from three large-sized manufacturing companies in Japan. The total sample was further divided into 450 independently matched subordinate–supervisor dyads. The human resources (HR) departments of the participating companies were responsible for administering the self-reported surveys. We instructed HR personnel to distribute a large envelope containing two questionnaires (i.e., subordinate and supervisor questionnaires), both of which were sealed in two separate smaller envelopes, to each participating subordinate. The participating subordinates were then instructed to complete their own questionnaire and give the other sealed envelope to their immediate supervisor. To avoid comparison biases that can potentially arise, a supervisor only assessed one of their subordinates on his/her career growth potential, not more than this. Furthermore, to match dyadic data sources, we adopted a coding system. All participants returned their completed questionnaires directly to the HR department. After we removed questionnaires with mismatched dyads and missing responses, the final sample comprised 399 subordinate–supervisor dyads, representing a valid response rate of 88.7%. Among the focal employees, 72.9% were male, the average age was 37.27 years, and the average tenure was 17.08 years. Importantly, our participants came from various functional departments (e.g., marketing, quality control, production, human resource, etc.) and across organizational levels (e.g., nonsupervisory employees, line management, middle management, and top management).

Measures

Unless otherwise indicated, the response format for the following scale items was a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). Given that English is not a native language for the Japanese participants, we adopted the back-translation procedure when developing the questionnaire surveys.

Political skill

Subordinates reported their political skill using the 18-item scale developed by Ferris et al. (Reference Ferris, Treadway, Kolodinsky, Hochwarter, Kacmar, Douglas and Frink2005). Example items include ‘I spend a lot of time and effort at work networking with others’ and ‘I have good intuition or savvy about how to present myself to others.’ In this study, Cronbach's α was .87.

Supervisor-focused expressive network resources

Subordinates rated the extent to which expressive network resources were available to them through their relationships with their immediate supervisors using the three-item subscale of network resources measure developed by Bozionelos (Reference Bozionelos2003). Example items include ‘I share emotional support, feedback, and work confirmation with my immediate supervisor’ and ‘I frequently talk to my supervisor about work-related topics.’ In this study, Cronbach's α was .75.

Supervisor developmental feedback

Subordinates also determined the extent to which they received developmental feedback from their supervisors using the three-item scale developed by Zhou (Reference Zhou2003). Example items are ‘While giving me feedback, my supervisor focuses on helping me to learn and improve’ and ‘My supervisor provides me with useful information on how to improve my job performance.’ The scale yielded a reliability coefficient of .72.

Ingratiation

Subordinates rated how often they exercised ingratiation toward their immediate supervisors on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from never (1) to very often (7), using the four-item subscale of impression management measure developed by Bolino and Turnley (Reference Bolino and Turnley1999). Sample items are ‘I praise my supervisor for their accomplishments, so they consider me a nice person’ and ‘I do personal favors for my supervisor to show them that I am friendly.’ The scale yielded a reliability coefficient of .76.

Career growth potential

Supervisors assessed the focal employee's career growth potential using the two-item scale developed by Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Liu and Wu2010). The two items are ‘This employee will attain his or her career goals in this organization’ and ‘This employee will receive growth and development opportunities in this organization.’ Given that supervisors had to determine their employees' achievement of personal career goals, some challenges may arise, as supervisors may not accurately assess employees' career goals. To preempt this issue, we first asked focal employees to indicate their ‘career aspirations in the next 5 years’ on a separate sheet of paper and instructed them to share this sheet with their supervisors for evaluating the employee's career growth potential. The scale yielded a Spearman–Brown coefficient of .86.

Control variables

Following conventions on the research in careers (McClelland, Barker, & Oh, Reference McClelland, Barker and Oh2012; Stroh, Brett, & Reilly, Reference Stroh, Brett and Reilly1992; Thacker & Wayne, Reference Thacker and Wayne1995), we controlled for employees' demographic attributes, including age, gender, and organizational tenure, to minimize confounding effects and rule out alternative explanations.

Results

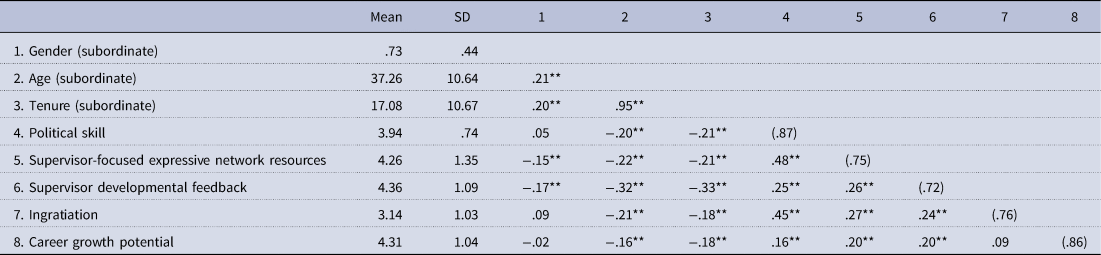

Descriptive statistics (i.e., means and standard deviations), zero-order correlations, and reliability estimates are presented in Table 1. The key variables of interest all exhibited acceptable reliabilities, with reliability coefficients of at least .70 (Kline, Reference Kline1999; Nunnally, Reference Nunnally1978). In terms of multicollinearity, except for the relationship between age and tenure, both of which are control variables, none of the remaining zero-order correlations exceeded .75.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, zero-order correlations and reliability estimates

Note: N = 399; *p < .05, **p < .01. SD = standard deviation.

Hypotheses testing

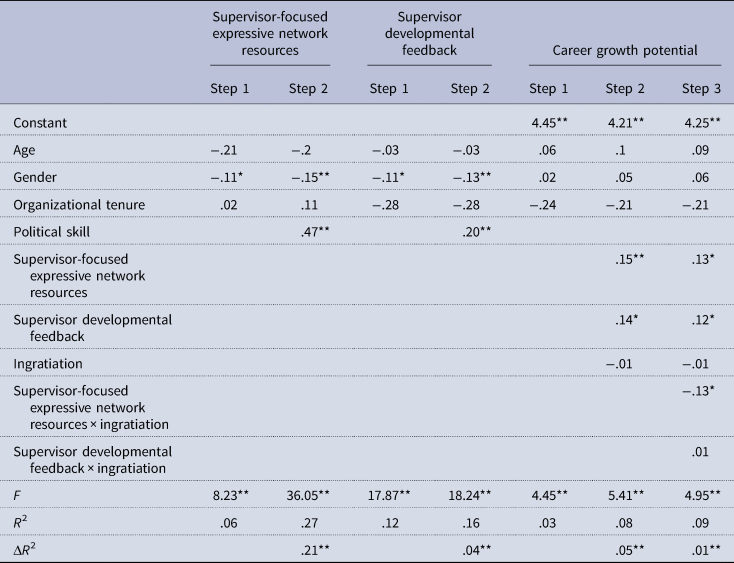

First, we proposed that political skill predicted the acquisition of social resources, notably supervisor-focused expressive network resources and supervisor developmental feedback. Using the IBM SPSS statistics 26 to run multiple regression analyses, our results revealed a positive and statistically significant relationship between (a) political skill and expressive network resources (β = .47, p < .01) and between (b) political skill and developmental feedback (β = .20, p < .01), fully supporting Hypothesis 1. We further hypothesized that the two social resources would promote career growth potential. Accordingly, our regression results showed a positive and statistically significant relationship between (a) expressive network resources and career growth potential (β = .15, p < .01) as well as between (b) developmental feedback and career growth potential (β = .14, p < .05), further supporting Hypothesis 2. These results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Regression results for supervisor-focused expressive network resources, supervisor developmental feedback, and career growth potential

Note: N = 399; *p < .05, **p < .01.

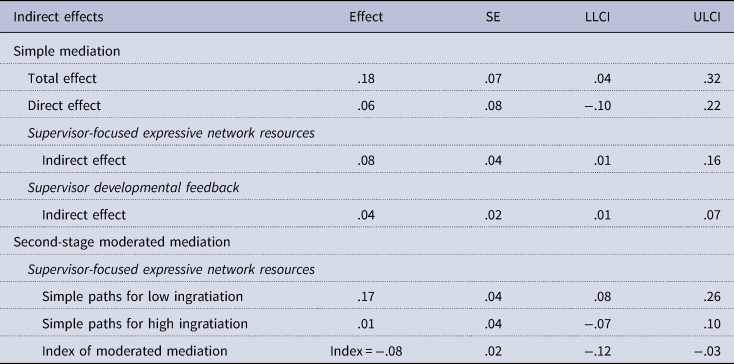

We then used the PROCESS macro developed by Hayes (Reference Hayes2013) to test the mediation and moderated mediation hypotheses. Following MacKinnon, Lockwood, and Williams (Reference MacKinnon, Lockwood and Williams2004), all indirect and conditional indirect effects were tested based on 5,000 bootstrapping resamples. Hypothesis 3 proposed that the two social resources, including supervisor-focused expressive network resources and supervisor developmental feedback, accounted for mediating mechanisms through which political skill promoted career growth potential. As shown in Table 3, the indirect effect of political skill on career growth potential via (a) expressive network resources [indirect effect = .08, SE = .04, 95% confidence interval (CI) = .01–.16] and (b) developmental feedback [indirect effect = .04, SE = .02, 95% confidence interval (CI) = .01–.07] was positive and significant. Hence, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Table 3. Regression results for the indirect effect and conditional indirect effect of political skill on career growth potential through (a) supervisor-focused expressive network resources and (b) supervisor developmental feedback

Note: N = 399. Bootstrap sample size = 5,000. SE = standard error; LLCI = lower limit confidence interval; ULCI = upper limit confidence interval.

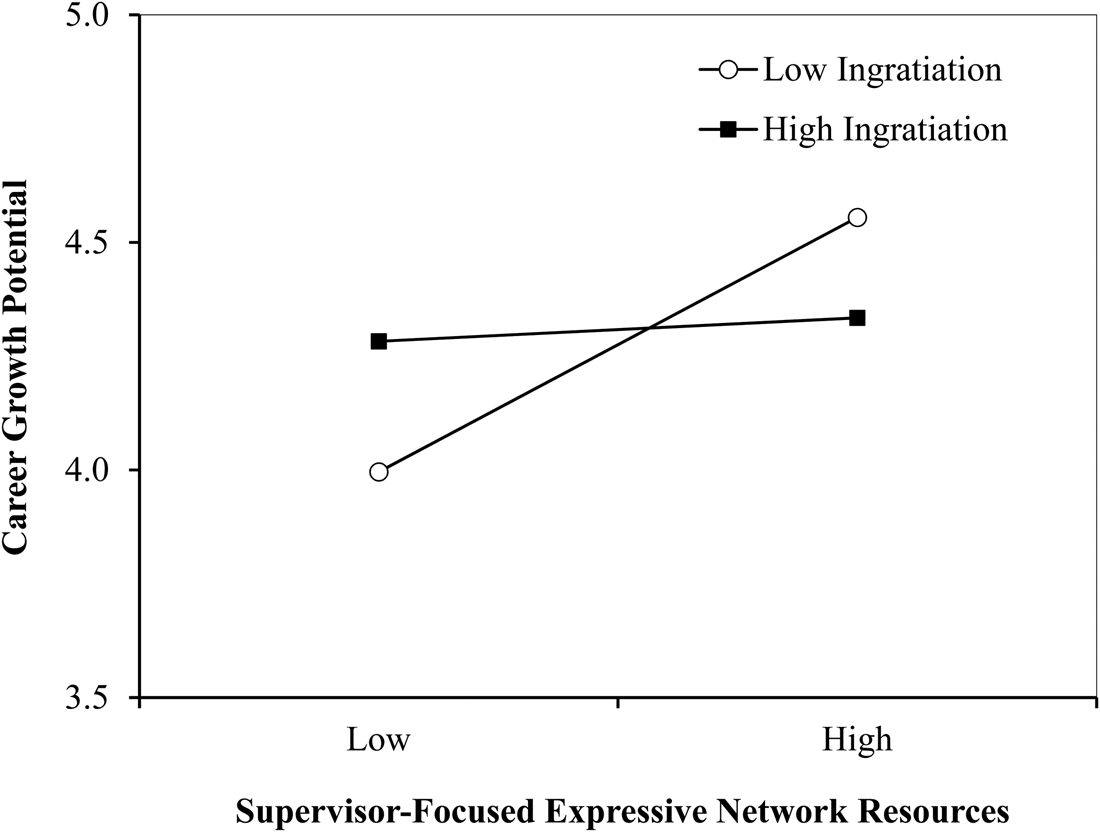

We turn next to Hypothesis 4, which predicted that the strength of the indirect effect of political skill on career growth potential via (a) supervisor-focused expressive network resources and (b) supervisor developmental feedback would depend on the use of ingratiation. Specifically, Hypothesis 4 proposed the second-stage moderation such that the positive mediating relationship would grow stronger at higher levels of ingratiation. First, considering the interaction between expressive network resources and ingratiation in predicting career growth potential, we observed a statistically significant interaction term, but the direction of the moderating impact was rather negative (β = −.14, p < .01) (see Table 2), which contradicts our initial prediction. As shown in Figure 2, supervisor-focused expressive network resources were associated with career growth potential at low levels of ingratiation (β = .21, p < .01) but not at high levels (β = .02, p < .73). Similarly, the conditional indirect effect of political skill on career growth potential strengthened at low levels of ingratiation (indirect effect = .17, SE = .04, 95% CI = .08–.26) but became nonsignificant at high levels of ingratiation (indirect effect = .01, SE = .04, 95% CI = −.07 to .10). Turning next to the interaction between supervisor developmental feedback and ingratiation in predicting career growth potential, we did not observe a statistically significant interaction term for this proposed relationship (β = .01, p = 81) (see Table 2). Hence, the corresponding conditional indirect effect was no longer estimated. In sum, we can conclude that Hypothesis 4 was not empirically supported. The moderated mediation results are summarized in Table 3. The implications of these results are discussed further in the text.

Figure 2. The interactive association between supervisor-focused expressive network resources and ingratiation in predicting career growth potential.

Discussion

This study employs the Japanese work context to explicate the link between political skill and career growth potential. One major rationale for choosing this context is that career progression among Japanese employees is closely linked to the quality of networks they have developed with others who are significant to their work life (Erez, Reference Erez1992). According to social resources theory (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Ensel and Vaughn1981), relationship building precedes the acquisition of resources that are instrumental to achieving personal goals. Through active networking and their ability to be convincing, employees high in political skill are better able to secure the support, feedback, and information needed for their career growth. Correspondingly, our findings revealed that exercising political skill resulted in greater access to social resources, notably supervisor-focused expressive network resources and supervisor developmental feedback, both of which further enhanced employee career growth potential. Furthermore, although our results revealed that ingratiation operated meaningfully as a second-stage boundary condition in the proposed research model, the way it affected the utilization of the social resources obtained from having exercised political skill contradicts our initial prediction. Specifically, while supervisor-focused expressive network resources were positively associated with career growth potential when employees exercised ingratiation less frequently, the moderating impact of ingratiation was nonsignificant for supervisor developmental feedback. One common theme from these results is that once individuals have developed close interpersonal relationships with their supervisors and got access to the resources needed for career growth, resorting to using ingratiation becomes insignificant. Both theoretical and practical implications for the obtained results are discussed further in the text.

Theoretical implications

This study provides important implications for the career growth literature. First, the development of our proposed model is informed by the contemporary career circumstances facing Japanese employees. As noted by Weng and Zhu (Reference Weng and Zhu2020) in their review paper, research on career growth should take a more context-specific approach because career growth is inevitably influenced by the context in which it occurs, such as economic situations, cultural backgrounds, etc. While Japanese firms were once known for offering lifelong employment for their employees, many companies now struggle to offer the same support since the collapse of the ‘bubble’ economy in the late 1990s (Kuroda & Yamamoto, Reference Kuroda and Yamamoto2005). Given the new situation, many employees now realize the importance of developing and managing their own careers (Taniguchi et al., Reference Taniguchi, Kato and Suzuki2006). In this regard, we highlight political skill as an important interpersonal competency that individuals can draw on to exert control over their career course. Using social resources theory (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Ensel and Vaughn1981), relationship building enables individuals' access to support, organizational information, and feedback on work-related issues from their supervisors, further promoting their career growth potential. Due to key qualities such as social astuteness and networking ability, political skill can explain why some employees are adept in recognizing opportunities from building strong relationships with their supervisors. In addition, due to key qualities such as interpersonal influence and apparent sincerity, political skill helps explain how individuals can effectively engage in interpersonal interactions with their supervisors (McAllister et al., Reference McAllister, Ellen and Ferris2018). In support of this, our results revealed that political skill predicted employees' access to social resources, notably supervisor-focused expressive network resources and supervisor developmental feedback.

Second, for a more fine-grained understanding of which social resources would be instrumental to achieving career growth in the Japanese work context, our proposed model is further informed by its dominant cultural features, notably high collectivism and high uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1984). In a highly collectivistic culture, people strongly value group membership, which further explains the tendency of individuals to engage in interpersonal relationships. In a high uncertainty avoidance culture, people tend to feel uneasy in ambiguous situations, which explains the propensity of individuals to build relationships with more senior staff, such as their supervisors, since these people can offer important information that helps reduce uncertainty about the organizational environment (Bozionelos, Reference Bozionelos2006; Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001). Given the interpersonal focus of the Japanese work culture, we cast a spotlight on resources that are interpersonally sought from the employee's supervisor, including supervisor-focused expressive network resources and supervisor developmental feedback. As informed by social resources theory (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Ensel and Vaughn1981), the nature of the resources obtained from relationship building is important in achieving personal objectives. Accordingly, our results revealed that expressive network resources and developmental feedback from supervisors accounted for mediating mechanisms through which political skill predicted career growth potential.

Importantly, the question ‘why do some employees experience more successful career mobility?’ still requires further explanation and empirical support (Weng & Zhu, Reference Weng and Zhu2020). Given that career growth is a form of upward movement in an organization, our study enables a better understanding of how expressive network resources and developmental feedback from supervisors can aid career growth. Thus far, the research has largely underscored the role of instrumental network resources, which serve functions such as exposure to top management, professional advice, and access to job-related information, in obtaining extrinsic career outcomes (Bozionelos, Reference Bozionelos2003; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000). In contrast, because the primary function of expressive network resources is to provide friendship and emotional support (Bozionelos, Reference Bozionelos2003), there is rather limited research done to uncover their potential in promoting employees' career mobility (e.g., Chen, Chang, & Chiang, Reference Chen, Chang and Chiang2017). Our argument is that expressive network resources consist of strong connections among organizational members, which foster trust and cooperation, thereby facilitating an exchange of valued resources that can enhance one's career growth potential (Brass, Reference Brass1984). A similar pattern can be observed for supervisor developmental feedback. To the best of our understanding, research has thus far determined the work-related behaviors of developmental feedback, including task performance, helping behaviors and creative behaviors (Li et al., Reference Li, Harris, Boswell and Xie2011; Zhou, Reference Zhou2003). Due to the future-oriented nature of the developmental feedback that is aimed toward improving one's performance and other aspects of their work life (George & Zhou, Reference George and Zhou2007), it should be highly useful in promoting longer-term outcomes, such as career growth. Our study provides empirical support for the instrumental role that both supervisor-focused expressive network resources and supervisor developmental feedback can serve in promoting one's career growth potential.

Finally, although the acquired results did not support our initial prediction pertaining to the moderating impact of ingratiation, we obtained unique insight into exactly how ingratiation intervenes in the proposed relationship among political skill, expressive network resources and developmental feedback from supervisors, and career growth potential. That is, as employees have already developed favorable connections with their supervisors and subsequently accessed the necessary resources for career growth, exercising ingratiation toward the supervisors would not help them leverage the available resources. For supervisor-focused expressive network resources in particular, our results suggest that employees would be better off if they exercised ingratiation less frequently. To explain this contradictory result, we draw on weak tie theory (Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1973) to offer an alternative perspective. The theory argues that relationship ties that employees develop with others can vary in strength. Strong ties can be described as closely-knitted relationships that are emotionally intense, have frequent contact, and involve multiple relationship types (Uzzi, Reference Uzzi1996). By contrast, weak ties can be described as not emotionally intense, having infrequent contact, and restricted to one narrow type of relationship (e.g., an acquaintance). While the key advantage of having strong ties is quick access to a greater amount of resources, the key advantage of having weak ties is access to rather unique resources (Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1973). Hence, when employees use ingratiation with someone whom they have already shared a strong tie, they may gain more of the same resources but no further unique resources that could create additional opportunities for career advancement. Strong ties tend to offer similar information and benefits because people within these relationships likely share similar social networks, which rather constrain their access to a variety of other resources (Seibert et al., Reference Seibert, Kraimer and Liden2001). Therefore, given that employees have already formed genuine relationships with their supervisors, using ingratiation to make oneself appear more likable is deemed insignificant.

Adding to the fact that employees have already formed genuine favorable relationships with their supervisors, an attempt to further engage ingratiation may instead be perceived as lacking genuineness and holding ulterior motives (Liu, Ferris, Xu, Weitz, & Perrewé, Reference Liu, Ferris, Xu, Weitz and Perrewé2014). Hence, while ingratiation may be exercised to enhance an individual's likeability in the eyes of others, ingratiation may as well backfire those who engage in the behavior if the tactic is not enacted in the right context, such as in a situation where strong interpersonal connections have already been established between employees and supervisors. Indeed, the success of ingratiation depends largely on the social context in which the tactic is used, which will have further impact on the extent to which personal motives underlying ingratiation can be detected (Jones & Pittman, Reference Jones, Pittman and Suls1982; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ferris, Xu, Weitz and Perrewé2014). This further explains why we did not receive empirical support for our hypothesized positive moderating impact of ingratiation.

Practical implications

This study provides important practical implications geared toward individual employees, supervisors, and organizations, especially those who face somewhat similar work and career circumstances as in Japan. First, due to the dynamics of the current business environment, characterized by high competition and uncertainty, Japanese firms can no longer guarantee lifelong employment for their employees. In this regard, many people have now realized the importance of taking charge of their own careers (Taniguchi et al., Reference Taniguchi, Kato and Suzuki2006). As reflected in our findings, employees can benefit from using their political skill. Unlike innate demographic characteristics and personality traits, political skill can be learned and developed over time (Ferris et al., Reference Ferris, Treadway, Perrewé, Brouer, Douglas and Lux2007). Employees can acquire this political savvy while at work. For instance, to sharpen their social astuteness, employees may take time to observe their surrounding work environment, understand its boundaries, and learn who the key players are in the organization. To master their interpersonal influence and networking ability, employees may become more active in taking part in professional social events organized by their employer and outside institutions. Organizations may offer training and opportunities that enable employees to practice interpersonal strategies associated with political skill, such as networking (Kacmar, Andrews, Harris, & Tepper, Reference Kacmar, Andrews, Harris and Tepper2013).

Second, because our proposed model is informed by some dominant features of the Japanese work culture, notably the work culture being highly collectivistic and high uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1984), the obtained results should particularly pertain to employees working in organizations that exhibit somewhat similar cultural values. Informed by these cultural characteristics, we emphasize relationship building as an important element in achieving career growth (Bozionelos, Reference Bozionelos2006; Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001). Given the value of the benefits embedded in supervisor-focused expressive network resources and supervisor developmental feedback, the extent to which employees will attain these resources may vary according to how close and favorable their relationships with their supervisors are. Nevertheless, it is important for organizations to recognize the relevance of making these resources, such as work confirmation, feedback related to work-life aspects, and important organizational information, available to everyone. If such support is lacking, employers may risk losing talent (Weng et al., Reference Weng, McElroy, Morrow and Liu2010). Hence, organizations may consider how they can give employees greater access to such support through work practices, such as mentoring, performance appraisal interviews, and career counseling services.

Our results also provide important caution for employees who attempt to further leverage the strong interpersonal relationships they have developed with their supervisors and the benefits embedded in these social ties. Specifically, using ingratiation with people whom employees are already closely connected is deemed ineffective. Once again, guided by weak tie theory (Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1973), we suggest that employees may instead consider how they can make use of ingratiation to build connections with other organizational members or even outside professionals whom they have not yet formed a strong tie. The key advantage of having weak ties is that people whom employees only know as acquaintances may be able to offer unique resources that they do not currently possess (Seibert et al., Reference Seibert, Kraimer and Liden2001). Such strategy of gearing toward developing ties with acquaintances outside the current professional circle should be particularly appealing to younger Japanese employees who seek to obtain career growth opportunities not only from their current employer but also from future organizations that they can potentially become a part of (Taniguchi et al., Reference Taniguchi, Kato and Suzuki2006). Career growth opportunities that individuals can obtain from new employers include more challenging assignments and promotions. Therefore, it is no longer taken for granted that employees will remain with one single organization throughout their career (Takase, Teraoka, & Yabase, Reference Takase, Teraoka and Yabase2016; Yanadori & Kato, Reference Yanadori and Kato2007). This is another reminder for organizations to ensure the accessibility and availability of career growth opportunities to their employees, such as job enrichment, training and development, and promotion opportunities, if they wish to retain their talents rather than to incur more costs for having to recruit new people.

Limitations and future research directions

However, this study also presents some limitations, which should be carefully considered when interpreting its results. First, we acknowledge the limitation of the career growth measure adopted in this study, which can only be used to infer employees' potential for career growth, not their actual growth. To capture an individual's career growth experience more thoroughly, future studies may consider adopting both objective and subjective measures of career-related outcomes. Examples of objective measures include the actual number of promotions, training programs, and other development opportunities one has obtained during their employment with the current organization (Ng, Eby, Sorensen, & Feldman, Reference Ng, Eby, Sorensen and Feldman2005). Subjective measures may include promotability ratings (i.e., the likelihood of being promoted to a higher organizational level) and career satisfaction (i.e., employees' subjective evaluations of their accomplishments of personal career goals) (London & Stumpf, Reference London and Stumpf1982).

Second, our data were obtained from companies operating in the manufacturing industry in Japan using a convenience sampling approach. Therefore, the empirical evidence shown in this study may not apply to other industries and cultural contexts. To generalize the study's results, future research may consider replicating these findings in different industries as well as in different cultural settings. Third, while we engaged with participants from various organizational levels, such as line management, middle management, and top management, we did not control for how employees' positional levels may affect our proposed relationships. For instance, Podolny and Baron (Reference Podolny and Baron1997) argued that organizational ranks may influence the acquisition of resources and subsequent career advancement. However, our control of organizational tenure as one form of an individual's seniority and experience within an organization is also noteworthy. Indeed, research revealed that tenure can have either a positive or negative impact on employee career progression (Bowman, Reference Bowman1964; McClelland et al., Reference McClelland, Barker and Oh2012; Thacker & Wayne, Reference Thacker and Wayne1995).

Finally, future research may build on this study by uncovering other potential mediating mechanisms through which employees high in political skill can increase their chances for career growth. Substantial research examines the moderating role of political skill, specifically its impact on the effectiveness of various social influence tactics, such as ingratiation, self-promotion, and rationality (Harris, Kacmar, Zivnuska, & Shaw, Reference Harris, Kacmar, Zivnuska and Shaw2007; Kolodinsky, Treadway, & Ferris, Reference Kolodinsky, Treadway and Ferris2007; Treadway et al., Reference Treadway, Breland, Williams, Cho, Yang and Ferris2013). However, what is currently lacking is a better understanding of how using political skill may translate into one's choice of specific influence strategies. That is, how do employees who are high in political skill go about achieving career growth through the exercise of social influence? Although the moderating role of ingratiation appears to be rather nonsignificant in our study, it may infer ‘how’ such a social influence tactic should play out in the research model, for instance, as a mediating mechanism that explicates the link between political skill and career growth potential. In fact, various social influence tactics have been increasingly recognized as effective career strategies, including ingratiation, self-promotion, and exemplification (King, Reference King2004; Sibunruang et al., Reference Sibunruang, Garcia and Tolentino2016).

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results provide an integrated understanding of how interpersonal competency (i.e., political skill), social resources (i.e., supervisor-focused expressive network resources and supervisor developmental feedback), strategic interpersonal behaviors (i.e., ingratiation), and career outcomes (i.e., career growth) play out as informed by the Japanese work context. Moreover, this study unfolds the potential of the expressive network resources and developmental feedback sourced from supervisors in achieving extrinsic career outcomes, notably career growth potential.

Hataya is a Senior Lecturer in Human Resource Management at the University of Waikato, New Zealand. She received her PhD in Management (Organizational Behaviour) from the Australian National University. Hataya is a research active faculty with publications in international outlets, such as Journal of Vocational Behavior, Journal of Career Assessment, and Handbook of Organizational Politics (2nd Edition).

Norifumi Kawai is an Associate Professor in Global Strategy in the Faculty of Economics at Sophia University, Japan. He holds a PhD in Managerial Economics from the Mercator School of Management at the Universität Duisburg-Essen, Germany. His articles have been published in Asian Business & Management, British Journal of Management, European Journal of International Management, Global Economic Review, International Business Review, International Journal of Gender & Entrepreneurship, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Journal of Small Business & Enterprise Development, and Journal of World Business.