Eduard Verhagen: Opening Argument in the Affirmative

In defense of the affirmative position, I will describe how in the Netherlands, over a period of roughly 20 years, euthanasia has gradually expanded to the pediatric population. I will describe the relevant developments in end-of-life care, first for newborns 0–12 months of age and then for children 1–12 years of age. From the description, it will become evident that the steps toward expansion are based on the results of several end-of-life studies and the consistent request by parents and medical professionals who are willing to perform euthanasia for patients with unbearable suffering. I will argue that in addition to those arguments, expansion of euthanasia to include children is ethically justifiable and can be regulated and legalized safely.

Death and Dying in the Pediatric Population

At the end of life, many patients need comfort-oriented care and such care frequently includes end-of-life decisionmaking. Definitions are important in this context: End-of-life decisions are medical decisions that cause or hasten death, and the most frequent ones in pediatrics are the decision to

-

1. Withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment

-

2. Use comfort medication (e.g., morphine, midazolam) that may shorten life

-

3. Provide “euthanasia.” For the sake of simplicity, I define euthanasia as deliberate life ending on the patient’s or parents’ request.

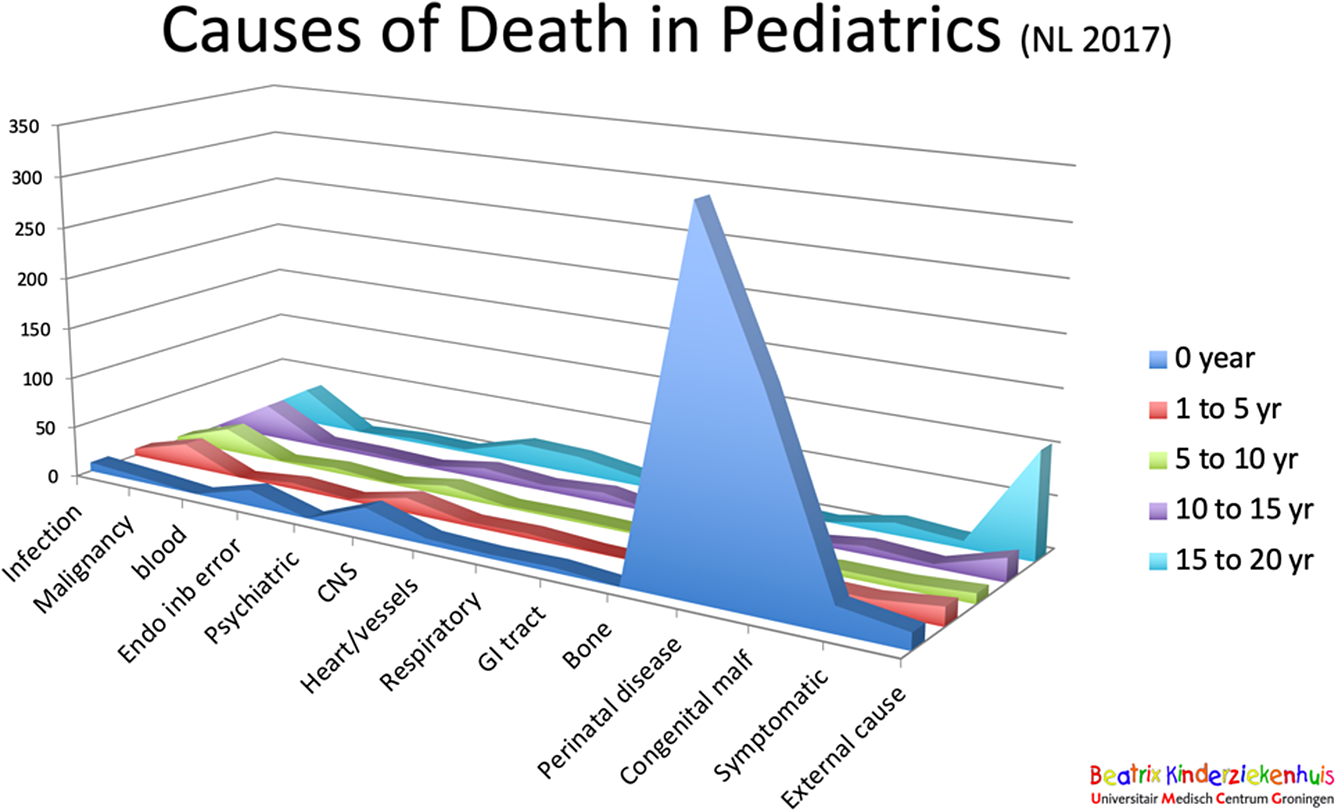

Death in the pediatric population is uncommon in comparison to death in adults (1:150). In the Netherlands, around 1,000 pediatric deaths occur each year and the overwhelming majority are among newborns 0–12 months of age with perinatal conditions and/or congenital malformations. In other age groups, mortality is low and concerns many different rare conditions. Except for the first year of life, there are no real mortality peaks until the age of 15–20 years when suicide and traffic accidents become important causes of death (Figure 1). This mortality pattern, which is similar in most industrialized countries, makes it understandable that most of the studies on death and dying in pediatrics are in the newborn population. That is simply where the highest numbers are.

Figure 1 Causes of death in children (the Netherlands 2017).

How Do Babies Die?

In the Netherlands, surveys that describe end-of-life practice for adults and newborns are published every 5 years. The data from the surveys between 1995 and 2005 show that around 60 percent of deaths was due to withholding or withdrawing life support, around 24 percent died while medication was administered while shorting of life was not intended, and for around 5 percent of deaths, medication was administered with the explicit intention of shortening the newborn’s life. From the last category, we can conclude that neonatal euthanasia was actually part of medical practice at the time, but nobody really knew why and how and what the diagnosis was of these newborn patients. All those details were largely unknown because the surveys were anonymous, and reporting didn’t take place.

Around the time of these surveys, a patient named Bente was referred to us at the University of Groningen hospital, because she appeared to have some kind of skin disease. She was not ill but her skin was fragile with blisters and she developed painful scars on her hand, feet, and vocal cords. She suffered from a lethal type of Epidermolysis Bullosa. Hugging or rubbing would make her skin come off, which was extremely painful. There is no cure for this condition, and most babies die in the first weeks or months of life due to failure to thrive, an affected airway, or sepsis. Bente was one of them, and after studying the Internet, her parents asked us to end the life of their child because they did not want her to suffer badly. They knew that the suffering was going to be intense and would become even more unbearable with every week. They simply did not want that for their child.

The medical team understood their request and agreed that death would probably be a better option than months of sustained suffering, but at the same time, we were afraid to end the life of Bente because of the legal consequences. We could be arrested and prosecuted for murder or homicide. So, after days of deliberation, we decided to send Bente back to the hospital that had referred her to us. That is where she died 3 months later, and those 3 months were terrible.

The Groningen Protocol for Euthanasia in Newborns (0–12 Months)

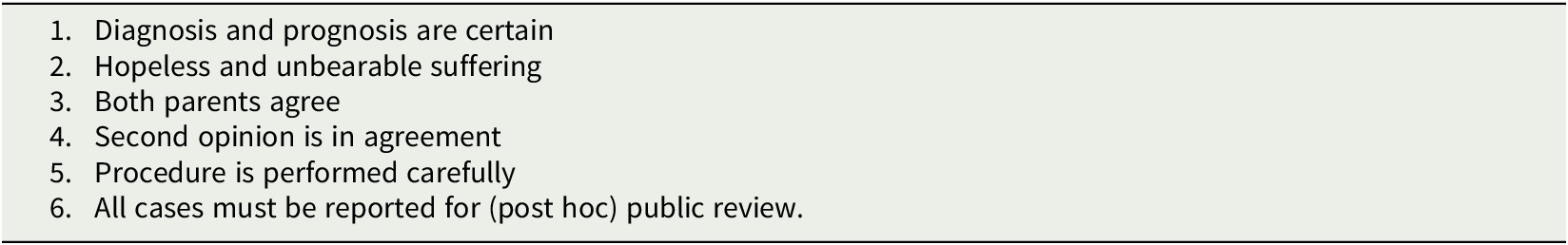

Bente’s death made us rethink our end-of-life policies, and based on this case and the verdicts in two court cases, we published a protocol that would allow us to make a different choice in future cases. This protocol became a national document and became internationally known as “the Groningen Protocol for severely ill newborns.” Its publication had two goals. The first was to provide a careful framework for making decisions about newborn euthanasia in stable newborns, like Bente, with sustained suffering in situations where no life-supportive treatments are left to withhold or withdraw. The second was to start regulating the existing practice of newborn euthanasia, as was shown in the surveys, and make it more transparent. In Table 1, the protocol’s requirements are reported. They are almost identical to the requirement in the Dutch 2002 euthanasia law for adults and children of 12 years and above. The ethical justification is a combination of parental determination and beneficence. Legally, the protocol was transformed into a regulation supported by the ministries of justice and health, welfare, and sports. After regulation, the surveys showed a decrease in newborn euthanasia cases to zero in 2015.

Table 1. Requirements of the Groningen Protocol

Euthanasia in Children 1–12 Years Old

After the successful legalization of newborn euthanasia, new questions arose around 2014 when parents and physicians publicly questioned why severely ill children older than 1 year and their parents were denied access to the same end-of-life provisions as newborns and their parents. Why was pediatric euthanasia restricted to newborns and not extended as an option for older children?

A consortium of researchers addressed this question by initiating a study on how children between 1 and 12 years old die. This was largely unknown and unstudied, presumably because the number of patients had always been very low. The reports of that study showed that hopeless and unbearable suffering in dying children did indeed occur in several cases, which was confirmed by both parents and physicians. No euthanasia cases were found. Physicians indicated that they experienced a gray area between palliative sedation and euthanasia. Clarification of the boundaries beyond the current pediatric guidelines was extremely relevant to them because palliative sedation is legally labeled as “normal medical practice,” but euthanasia in this age group is a criminal offense. Many of the participating pediatricians reported that even when the patient’s suffering could not be controlled by palliative sedation, they would always err on the side of legal caution and accept the suffering rather than hasten death with the risk of prosecution. Based on the study results, the researchers formulated several recommendations aimed at improving the quality and accessibility of pediatric palliative care. In addition, they recommend to make euthanasia for children 1–12 years a legal option in line with the request made by parents and physicians. The study results were presented to the Dutch minister of health, welfare, and sports, who adopted the recommendations and successfully defended them in parliament. At the end of 2020, he announced the preparations for a legal regulation allowing euthanasia for 1- to 12- year-olds under strict circumstances and strict conditions. The final version of this regulation is expected at the end of 2021.

Conclusion

The practice of neonatal euthanasia on parental request is thoroughly studied, legally regulated, and end-of-life practice is monitored continuously. For children of ages 1–12 years old, examination of death and dying showed that unbearable suffering at the end of life is a reality for some patients. Parents and physicians caring for children request for euthanasia as a legal option, and parliament has agreed. The legal regulation is expected to be finalized soon.

Should euthanasia be expanded to include children? Yes, and fortunately that process is almost completed.

Martin Buijsen: Opening Argument in the Negative

Thank you. I would like to begin by rephrasing the question, because the question is somewhat lacking in nuance. In my view, the question should read as follows:

Is The Netherlands Allowed to Introduce Legislation to Expand the Law on Euthanasia to Include Children?

This rephrasing of the question is not a rhetorical trick on my part. I do not want to take the debate to another arena. But I want to make clear that the issue is one of the basic rights. In countries where rule of law exists, the law is not merely the tail end of policymaking. Policymaking can indeed result in law, that is, in legislation, but it is itself governed by law as well, by a higher law. National policymaking is subject to (international) human rights law, and that is what I would like to focus on.

In this debate, proponents of “bridging the gap” always present the current state of affairs in the same way. In the Netherlands, we have a Euthanasia Act, applicable to children ages 12 and over, and there is a Ministerial regulation establishing a review committee on late term abortions and termination of life of severely suffering neonates not older than 1 year. And in between we have nothing. For children of that age category (from 1 to 12), they argue, something ought to be done as well.

The Dutch Euthanasia Act is well known. According to the Dutch Criminal Code, termination of life on request and suicide assistance are criminal offenses. However, if such an act is performed by a physician who acted in compliance with the so-called due care criteria of the Act and who subsequently notified the municipal pathologist, the competent regional euthanasia review committee will not inform the Public Prosecution Service if it afterward rules that he or she did indeed meet the statutory due care requirements. Two criteria are especially relevant:

-

1. The physician must be satisfied that the patient’s request is voluntary and well-considered.

-

2. The physician must be satisfied that the patient’s suffering is unbearable and without the prospect of improvement.

The Euthanasia Act applies to patients aged 12 or over, but there are differences in terms of parental involvement and agreement. According to the Act, if the patient is a minor aged between 16 and 18 and is deemed capable of making a reasonable appraisal of his or her own interests, the physician may comply with a request made by the patient to terminate his or her life or provide suicide assistance, after the parent or parents who have the responsibility, or else the guardian, has or have been consulted. If the patient is a minor aged between 12 and 16 and is deemed capable of making a reasonable appraisal of his or her own interests, the physician may, if a parent or the parents who have the responsibility, or else the guardian, can agree to the termination of life or to assisted suicide, comply with the patient’s request.

And now the Groningen Protocol, as it is known nowadays, laid down in the aforementioned Ministerial regulation establishing a review committee on late term abortions and termination of life of severely suffering neonates not older than 1 year. Of course, murder and homicide are criminal offenses. But according to the regulation, a physician who terminates the life of a severely suffering newborn not older than 1 year has to notify the municipal pathologist, who in turn will inform the Public Prosecution Service (PPS), which will seek the advice of a (national) committee on late term abortions and termination of life of severely suffering neonates. This committee too will assess whether the physician acted in compliance with due care criteria. And on the basis of that advice, the PPS will decide whether to prosecute.

If we take a look at the due care criteria of that Ministerial regulation, we will see that they resemble those of the Euthanasia Act in many respects. They are not that different. The regulation states that the physician acted with due care if

-

1. In the physician’s opinion, there is hopeless and unbearable suffering of the newborn, which means, among other things, that the discontinuation of medical treatment is justified, that is, that according to prevailing medical opinion, it is certain that intervention is pointless and according to prevailing medical opinion, there is no reasonable doubt about the diagnosis and the subsequent prognosis.

-

2. The physician fully informed the parents of the diagnosis and the prognosis based on it, and that he or she came to the conclusion—together with the parents—that there was no reasonable other solution for the situation in which the newborn found himself or herself.

-

3. The parents have consented to the termination of life.

-

4. The physician has consulted at least one other independent physician, who has given his or her opinion in writing regarding the aforementioned standards of care, or, if an independent physician could not reasonably be consulted, has consulted the treatment team, which has given its opinion in writing regarding the aforementioned standards of care.

-

5. The termination of life was carried out with due medical care.

Now, what about severely suffering children ages 1–12? The claim that no rules exist for children ages 1–12 is simply not true. The Dutch Criminal Code does contain provisions regarding murder and homicide, but it also recognizes something which is commonly referred to as force majeure: “Not punishable is he who commits an act to which he is compelled by force majeure.” And a conflict of duties, as we know too well, may constitute force majeure.

So, there are rules but these are simply considered undesirable by some, notably the Dutch Association of Pediatricians. The proponents of “bridging the gap” for severely suffering children ages 1–12 will favor regulation modeled after the Euthanasia Act, after the Ministerial regulation, or after both.

And this is where my problems as a legal scholar begin. I am not putting forward moral (pro-life) arguments, I am merely pointing out fundamental legal difficulties. I have no such difficulties with the Euthanasia Act, at least not grosso modo, but the Ministerial regulation establishing a review committee on late term abortions and termination of life of severely suffering neonates not older than 1 year… Well, that is another matter.

Here is why. The protection of fundamental rights is guaranteed by the Dutch Constitution. But with a proviso. “Subject to limitations to be set by or pursuant to Act of Parliament” is always added. Take Article 11: “Everyone has the right to the inviolability of his body, subject to limitations to be set by or pursuant to Act of Parliament.” The Ministerial regulation establishing a review committee on late term abortions and termination of life of severely suffering neonates is not an Act of Parliament (i.e., statutory law) itself and it is not pursuant to any Act of Parliament. In effect, it is a regulation made by two government ministers (Justice and Health) who have not been given the authority to do so. The practice is not regulated at all, that is, properly speaking, in the legal sense. But that is not all.

The Dutch Constitution contains a number of other relevant provisions. According to Article 93, “provisions of treaties and of decisions of international organizations, which bind everyone by virtue of their content, have binding force after they have been published.” These are so-called self-executing treaty provisions. Such provisions do not need to be translated into national legislation first. No intervention by the Dutch legislature is needed. They automatically become part of the legal order. This constitutional provision is followed by Article 94: “Statutory regulations applicable within the Kingdom shall not be applied if such application is not compatible with provisions of treaties and of decisions of international organizations binding everyone.” Lex superior derogat legi inferiori…

Now, the Netherlands is a party to numerous international and European human rights treaties. The most important one is the European Convention on the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (the European Human Rights Convention, 1950), which came about as a response to the atrocities of the Second World War. It consists solely of self-executing (first generation) human rights provisions, also enforceable by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) residing in Strasbourg.

Two provisions are particularly relevant. Article 2 of the Convention states that no one shall be deprived of his life intentionally. No such right to life is mentioned in the Dutch Constitution. The right to life is nevertheless protected in the Netherlands since the Netherlands is a party to the Convention and the provision of Article 2 is self-executing. Another self-executing provision is also of interest. That of Article 8: “Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence.” This is what is called the right to privacy, which also includes—according to ECHR case law—personal inviolability.

For the Court in Strasbourg, which is the interpretive authority, the European Human Rights Convention is a living instrument to be interpreted according to present-day circumstances. As it happens, it has interpreted the provisions of Articles 2 and 8 in this way in two relevant cases of assisted suicide involving competent adults: the cases of Pretty (2002) and Haas (2011). In its ruling in the Haas case, the following was considered by the Court: “An individual’s right to decide by what means and at what point his or her life will end, provided he or she is capable of freely reaching a decision on this question and acting in consequence, is one of the aspects of the right to respect for private life within the meaning of Article 8 of the Convention.”

Article 2 of the Convention, originally meant to protect against unlawful killings by the state but also interpreted by the Court according to present-day circumstances, creates “a duty to protect vulnerable persons, even against actions by which they endanger their own lives.” According to the Court, Article 2 obliges national authorities “to prevent individuals from taking their own lives if they cannot take such decisions freely and with full understanding of what is involved.”

So, concerning voluntary termination of life, this is the position of the European Court. Now, since the member states of the Council of Europe—those states party to the European Human Rights Convention—have different views on voluntary termination of life, Article 8 (so the Court has said) does not imply a positive state obligation to facilitate voluntary termination of life, but states may choose to do so. Since the views of the states are divergent, the Strasbourg court adopts a wide margin of appreciation. As regards the extent of interference by public authorities with the exercise of the right protected by Article 8, and that is to be done on the basis of the second paragraph of Article 8, that it is up to the state. The state has to weigh the relevant interests. However, that interference may not be such that everyone’s right to choose the time and manner of death, turns out to be merely “theoretical and illusory.” But, and that is the other side, the other point of reference so to speak, it may also not be such as that the lives of the vulnerable are endangered.

What does this all mean? Well, there is little doubt that the Dutch Euthanasia Act is within the margin of appreciation. It is not at odds with both self-executing provisions of the European Human Rights Convention. The Ministerial regulation, however, clearly is. It does not fall within the margin of appreciation and is therefore in contravention with those provisions. Again, states may choose to facilitate voluntary deliberate termination of life, but the individual whose life is to be ended must be capable of freely reaching such a decision and acting in consequence. If a state does indeed make that choice, it is nevertheless obliged to protect the lives of those incapable to make such a decision. Therefore, to the extent that the desired rules for children between ages 1 and 12 are modeled after the Ministerial regulation, they will not be within the margin of appreciation. Such rules simply would not “fit.” And the law, as Ronald Dworkin has said, must be conceived as integrity.

What is an individual pediatrician to do with a child, suffering unbearably without the prospect of improvement, and unable to reasonably appraise its interests? Well, to those physicians I would say, as a lawyer, do what you always do as a clinician. Present the case to your team and—if necessary—to a local ethics committee. Deliberate! Get your facts straight, find out which values are at stake, see what options you have, identify all morally relevant arguments, weigh them, and reach an informed decision. But please do not forget the final step, which is of crucial importance. Check the consistency of your decision by putting it to the legality test. If you ultimately choose to end the life of a child under the age of 12, and what you are about to do you consider lawful, you must be willing to defend your decision publicly. And you must be willing to undergo public scrutiny. Fear of prosecution should never prevent a clinician to do what he or she sincerely considers to be morally right and lawful.

Eduard Verhagen’s Rebuttal: My Response to Martin Buijsen

The arguments of the other position are understandable, well formulated, and I think they are an important plea for reading the law well and using it well. I have developed a slightly different perspective. An important reason for many authors, including myself, to publish all these papers about how patients die, how babies and older children die, is the lack of sufficient knowledge at the level of lawmakers and other legal professionals about what is actually happening in practice at the bedside. We have tried to increase knowledge and enrich legal practice by giving more examples of practice dilemmas that should be solved. I have the feeling that we are succeeding after many years to accomplish a change, and that legalization of euthanasia might be connected to that effort.

There are two elements in the defense of the negative position that I would like to focus on. First of all, there is the argument that there is already a legal possibility for doctors to deliberately end the life of a child, based on the doctrine of “force majeure.” Extension of euthanasia beyond the current law would arguably be unnecessary. My reply would be that in theory, “force majeure” could act as a “safety valve” for the physician who ended a child’s life, to avoid prosecution. In practice, however, it doesn’t work. This route has been part of our penal law for decades, but it was hardly ever used for end-of-life care situations. In this context, the two landmark court cases are the Prins and Kadijk cases, named after the attending physicians that were prosecuted for newborn euthanasia in the 1990s. They were ultimately acquitted, based on the “force majeure” doctrine. Most Dutch pediatricians, even the younger ones, know the story of those two doctors, because they were severely harmed by the whole procedure and public media uproar, both professionally and personally. The Prins and Kadijk cases are generally seen as examples of the bluntness and inappropriateness of penal law as an interventional tool in complex medical cases. It is because of this bluntness that physicians are afraid to report their cases to the prosecutor or claim impunity on the basis of force majeure.

So, let us not stick to something that doesn’t work and hope it will magically start working in the future. Instead, let us try to enrich the law and make it suitable for medical practice. This was an important reason for making the Groningen Protocol in the first place: We knew that the “force majeure” route didn’t work and a better route had to be constructed to discourage physicians from covertly perform euthanasia. That is how we tried to repair the “safety valve” situation.

The second thing is that I think we should start taking parents seriously. Parents are the best representatives of the sick child, the state can’t do better; my guess is that neither of us can do better than the parents. So, if we allow parents a choice about the quality of their own death, why can’t we leave them a choice about the way their child will die? Our most recent study reporting on how children between 1 and 12 years die shows how devastating the process of dying is for some of these children. We will be reporting more about that soon. There is always a choice. There are many ways parents can choose and implement end-of-life decisions for their children. For example, many parents choose withholding or withdrawing intensive care at some point in time, some may rather choose withdrawal of artificial feeding and hydration, and, in rare cases, some parents may want to choose deliberate life ending to stop the intolerable suffering.

Martin Buijsen’s Rebuttal: My Response to Eduard Verhagen

What I really admire and appreciate is that Eduard’s contributions provide us with detailed information about pediatric practices at the end of life, that we gain insights and see the difficulties experienced by pediatricians treating severely ill children.

So that is admirable. But I am not a physician. I am not a healthcare professional. I am a lawyer. Law is hard and sometimes very uncomfortable to deal with. And rules are blunt by definition. That is also a fact. This is not—or at least not so much—about what an individual pediatrician feels is best for a particular severely suffering child given its parents’ wishes. It is about what we can do in terms of legislation in a state ruled by law.

Whether or not force majeure “works”… Well, ultimately, the criterion of competence is defining. As a legal scholar, I wouldn’t have any difficulties with legislation that abandons age criteria and—like the Belgian law on euthanasia—simply requires competency. That would be “fitting” rules. Such rules would be compatible with European human rights law. But there will always be children, including those not yet 1 year old of course, who just cannot make those decisions. And that is the really difficult category. Those cases should be looked at individually, by the PPS and—preferably—by a court of law. As a matter of principle, I don’t think you should set this principle aside because of the perceived burdensome nature of criminal prosecution by one party. Fear of prosecution should not be a motivating factor for one who sincerely believes to be right.

The second point Eduard made relates to the involvement of parents. Of course, I have no difficulties with parental involvement. But he seems to claim that parents are in the best possible position to decide. I hear Eduard say they should choose for their child what they would choose for themselves. But that is really very tricky. Parents may be very much in favor of euthanasia for themselves and—therefore—might want to have the life of their severely suffering newborn deliberately terminated. But what qualifies them as the best decisionmakers in these matters? There is little distance and there are strong emotional ties. After all, what is it that motivates them? Is it the pain of their child or is it their own suffering? Can you separate the two? I don’t know what it is that would make them the ones who are in the best possible position to reach an informed decision. So I have some reservations in that respect.

Again, from a legal point of view, I can’t object to legislation allowing for the performance of euthanasia on children in principle. But there has to be competence on their part. The child involved must be deemed capable of making a reasonable appraisal of its own interests in this regard. As far as incompetent children are concerned, legislation to that effect is simply impossible. Basic rights are at stake. According to the Dutch Constitution, limiting such rights can only be done by or pursuant to statutory law. But such a law would be at odds with European human rights law. Therefore, if an individual pediatrician sincerely considers it morally right to perform euthanasia on an incompetent child, he or she must be willing to defend that decision publicly, and to be scrutinized publicly, in a court of law.

Eduard Verhagen: Martin Buijsen’s Best Argument

There is a part of me, I must admit, that feels connected to what Martin brings forward. First of all, difficult cases that seem to be outside the law, should be dealt with by the prosecuting office and not by doctors. I agree with that. Even though the prosecuting office sometimes acts very thoughtlessly in healthcare matters, still I think this is a strong argument, and we should probably stick to that principle. I also feel that competency is an essential element in decisionmaking matters and we should always allow competent people to make autonomous healthcare decisions. At the same time, of course, we know that some children will never be competent and still decisions about end-of-life care need to be made. To me, young incompetent patients and parents are intimately connected as stakeholders. It is almost impossible to disconnect one from the other in end-of-life decisionmaking matters. Think about the gray area, where it is ambiguous whether a decision is in the child’s interest and reasonable people disagree about the right thing to do. Why not defer to the parents?

Martin Buijsen: Eduard Verhagen’s Best Argument

Eduard has put forward lots of very valuable arguments. And again, I admire the fact that issues like this are brought before the public in this way so that they can be discussed openly. It is important that the public knows what is happening in pediatrics and that it is aware of the extremely difficult positions pediatricians can find themselves in. I really appreciate that.

The patient’s request has taken center stage because of the Euthanasia Act. Recently, we had a notorious court case in the Netherlands, precisely on this issue. As Dutch, we are almost disciplined to reason analogically in these matters. If it is felt that regulation is needed, the rules should look like those of the Euthanasia Act. There ought to be due care criteria, notification, assessment afterward by a review panel of experts, and so forth. The Groningen Protocol was also inspired by it. But with a fundamental difference, of course, making the Ministerial regulation, which was modeled after the Protocol, extremely problematic.

Regulation of the deliberate ending of the lives of incompetent human beings is a no-go area. At the moment, that is something you simply cannot subject to proper rules of law. There is no doubt that everyone may decide when and how to die. The European Court of Human Rights has said as much. That is a private matter protected by the basic right to privacy. The exercise of that aspect of privacy is not enhanced but restricted by the Dutch Euthanasia Act. Even the more liberal Swiss laws on assisted suicide are to be seen as restrictions on the exercise of everyone’s right to decide on when and how to die. The extent to which the exercise of that right is restricted is for the state to determine, as long as the lives of those unable to make such decisions are protected. As a lawyer, I can only accept that—at the moment—there are no allowances made for restricting the exercise of the right to life by those who cannot themselves decide how and when to die. Statutory regulation is impossible. When the Dutch Council of State is going to assess the bill allowing the deliberate termination of the lives of incompetent human beings, it will not draw any other conclusion, nor will the Dutch Human Rights Committee. Eduard’s ideas are certainly worth exploring, but some things just do not lend themselves for regulation.