John Clare (1793–1864) was born in Helpston, Northamptonshire (Fig. 1). His father was a casual farm labourer with little schooling. John Clare himself worked as a ploughboy, reaper, thresher and pot-scourer. His first volume of poetry, Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery, was published in 1820 and was followed in 1821 by The Village Minstrel. Two further volumes of poetry followed: The Shepherd’s Calendar with Village Stories and Other Poems (1827) and The Rural Muse (1835). Clare was a prolific poet, writing well over 3500 poems. The principal themes of Clare’s poetry are ‘places and landscapes around Helpston, home and childhood, the seasons, and the bond between mood and nature’ (Reference BatesBates 2003: p. xxiv). Clare’s poetry has a unique quality; the best poems are carefully observed and reflect an awareness of nature that could only have come from a deep understanding and knowledge of his environment. Nature for Clare was not symbolic of some other, higher principle. Rather, the immediacy of his images is startling, often revealing his continuing pleasure, wonder and poetic response to the spectacle of life.

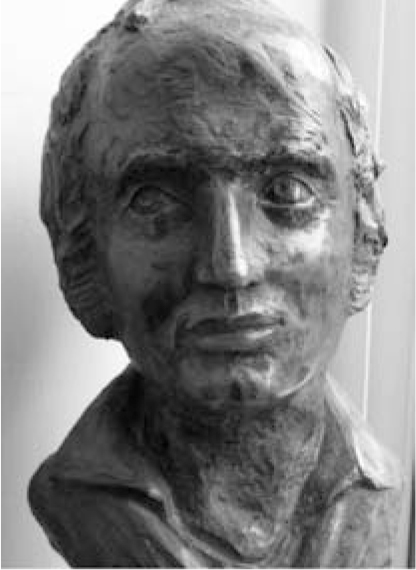

FIG 1 John Clare. Sculptor: Derek Wyndham Howells. © 2011, Leigh Howells.

In the poem ‘To the Fox Fern’, Clare writes:

In these few lines, with concision and economy, Clare conjures a world where the quality of light changes and dims as if it were sound and he effortlessly evokes a mood of melancholy with a few choice words. That was Clare’s gift: to be unassuming yet sure-footed in his chosen territory. In another poem, ‘The Skylark’, Clare wrote:

Bates has commented that ‘At first sight, Clare’s enumerations can make his work seem flat, as if in answer to the fenny flatlands of the eastern England that he knew. But a more attentive reading reveals that there is usually a circular motion in his writing, an answering not to the flatness of the land but to the curvature of the sky as it reaches towards the horizon’ (Reference BatesBates 2003: pp. xvii–xviii). I prefer to imagine Clare’s poetry as created to celebrate the moment. In this regard, although the poems have a dynamic quality in that there is inner movement and an aiming for something, yet the poems have the form of a word picture. That is to say that the poems also have a static and descriptive quality even when in motion. Time is slowed down to the pace of the rambler, and the poems render in high relief the material world, amplifying what is muted and dim so that they stand out for us almost as if they were statues. Surprisingly, this characteristic Clare shares in common with the classical Chinese poetry of Wang Wei (699–759) and Li Yu (937–978) (Reference Ch'en and BullockCh’en 1960).

Clare was admitted to High Beach Asylum, Epping Forest in July 1837 under the care of Dr Matthew Allen, where he remained for 4 years until, in July 1841, he walked out (or in today’s language, absconded). Recollections of journey from Essex is his account in prose of his journey from the asylum back home to Northborough, a distance of 80 miles covered in 4 days. In December 1841, Clare was certified insane for the second time and admitted to Northampton General Lunatic Asylum, where he remained until his death in 1864.

Recollections of journey from Essex

Clare was admitted to Fair Mead House, High Beach Asylum, Epping Forest on 16 July 1837. Dr Matthew Allen, a reforming psychiatrist who had adopted a mild system of treatment, eschewing fetters and restraints, ran High Beach Asylum. In the 2 years (1835–1837) leading up to this admission, Clare’s mental state had deteriorated. According to Frederick Reference MartinMartin (1865) in his biography, Clare’s ordinarily quiet behaviour gave way at times to fits of excitement, during which he would talk in a violent manner to those around him.

The immediate reason for his admission was his behaviour on a theatre outing in the company of Mrs Marsh, the Bishop of Peterborough’s wife. Martin takes up the account:

‘On the evening when Clare went to the theatre in company with Mrs. Marsh, the “Merchant of Venice” was performed. Clare sat and listened quietly while the first three acts were being played, not even replying to the questions as to how he liked the piece, addressed to him by Mrs. Marsh. But at the commencement of the fourth act, he got restless and evidently excited, and in the scene where Portia delivered judgment, he suddenly sprang up on his seat, and began addressing the actor who performed the part of Shylock. Great was the astonishment of all the good citizens of Peterborough, when a shrill voice, coming from the box reserved to the wife of the Lord Bishop, exclaimed, ‘You villain, you murderous villain!’ Such an utter breach of decorum was never heard of within the walls of the episcopal city. It was in vain that those nearest to Clare tried to keep him on his seat and induce him to be quiet; he kept shouting, louder than ever, and ended by making attempts to get upon the stage. At last, the performance had to be suspended’ (Reference MartinMartin 1865: p. 205).

In the spring of 1841, Clare made several unsuccessful attempts to escape High Beach. Despite this, Dr Allen continued to allow Clare freedom to move about the asylum grounds. In July 1841, Clare failed to return from a walk and searches for him proved unsuccessful.

Clare’s prose account of his escape from High Beach Asylum is probably the first such account. Clare left the asylum grounds on 20 July 1841, walking through Enfield Town before stopping for the night at Stevenage. He slept in a farmyard, lying on ‘some trusses of clover piled up about six or more feet square’ (Reference MartinMartin 1865: p. 258). He slept with his head pointing northwards to aid his ‘steering point’ next morning. On 21 July, Clare took the North Road. He records that ‘a man passed me on horseback in a slop-frock and said “here’s another of the broken-down haymakers” and threw me a penny’ (p. 258). It is unclear whether this was an auditory hallucination or not. Past Potton in Bedfordshire he was ‘hopping with a crippled foot’ because gravel had entered his old shoes. That night he first tried to settle down by a shed under some elm trees ‘but the wind came in between them so cold that I lay till I quaked like the ague and quitted the lodging’ (p. 260). In the end he settles on the front porch of ‘an odd house all alone near a wood’ (p. 261).

On the 22 and 23 July, Clare continued travelling north, passed through Buckden, Stilton, Peterborough, Walton and Werrington before reaching Northborough. One night, he slept at the bottom of a dyke and became thoroughly wet. He satisfied his hunger by eating ‘the grass by the wayside, which seemed to taste something like bread’ (p. 262). Clare recounts hearing people say things under their breath or indistinctly: ‘You’ll be noticed’, ‘poor creature’, ‘O he shams’ and ‘O no he don’t’. On the outskirts of Northborough, his wife Patty arrives in a cart to pick him up but he does not recognise her:

‘[I] was making for the Beehive as fast as I could when a cart passed me with a man and a woman and a boy in it – when nearing me the woman jumped out and caught fast hold of my hands and wished me to get into the cart but I refused and thought her either drunk or mad. But when I was told it was my second wife Patty I got in and was soon at Northborough, but Mary [his imaginary wife] was not there, neither could I get any information about her further than the old story of her being dead six years ago, which might be taken from a brand new old newspaper printed a dozen years ago, but I took no notice of the blarney having seen her myself about a twelvemonth [sic] ago alive and well and as young as ever’ (pp. 263–264).

Conclusions

Clare was certified insane by Messrs Skrimshaw and Page in December 1841 on the ground of being ‘addicted to poetical prosings’. Once again Frederick Martin takes up the account:

‘He struggled hard when the keepers came to fetch him, imploring them, with tears in his eyes, to leave him at his little cottage, and seeing all resistance fruitless, declaring his intention to die rather than to go to such another prison as that from which he had escaped. Of course, it was all in vain. The magic handwriting of Messrs. Fenwick Skrimshaw and William Page, backed by all the power of English law, soon got the upper hand, and the criminal “addicted to poetical prosings” was led away, and thrust into the gaol for insane at Northampton’ (p. 224).

This time Clare was committed to Northampton General Lunatic Asylum, where he remained for the last 23 years of his life. He continued to write poetry, which was transcribed by W. F. Knight, the asylum steward.

John Clare’s admissions were determined by his illness, but the particular asylum where he was treated was influenced by the funding arrangements. The admission into High Beach, a private asylum, was funded by benefactors, friends and well-wishers, whereas the later admission to the county asylum in Northampton was funded by Earl Fitzwilliam with a small sum, a county pension as it were, that entitled Clare to little more than pauper treatment. Nonetheless, Clare was well treated at Northampton. Dr Allen at High Beach had been prepared to take Clare back and was said to be hopeful of a cure, but this was not to be. Clare died on 20 May 1864. His last words were ‘I want to go home’.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.