1. Introduction

In her pioneering 1995 microcomparative work on Belfast English, Alison Henry discusses the fact that, for some Belfast speakers, overt imperative subjects can appear in a position following certain verbs (1).

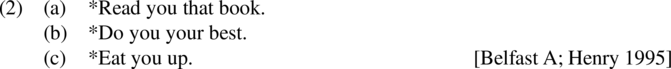

In this dialect, dubbed ‘Belfast A’ by Henry, only a subset of verbs allow for postverbal positioning of imperative subjects. While examples like (1) are grammatical, examples like (2) are ungrammatical in this dialect.

On this basis, Henry concludes that only subjects of unaccusatives or passive verbs can be postverbal in Belfast A imperatives; the postverbal position reflects these arguments’ underlying status as objects of their verbs. Henry proposes that the difference between Belfast A and standard English (StdE) can be located in a difference concerning the obligatory movement of subjects in imperative constructions.

This paper aims to elaborate the empirical and theoretical picture concerning variation between dialects of English by considering data from a dialect of Scottish English (ScotE), a variety closely related to Belfast and Ulster Englishes both historically and structurally. In the variety of Scottish English under consideration, postverbal imperative subjects are grammatical, but only with a very narrow range of verbs, narrower than in Belfast A. For example, the subject of motion get can appear after the verb and before a goal-indicating prepositional phrase (3).Footnote 2

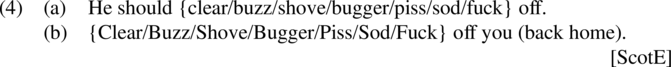

There are a very few other contexts in which a postverbal imperative subject is licit in this variety. One is with a class of verbs which I shall refer to as ‘taboo off’ verbs, a class of ‘rude’ verbs of motion containing the particle off (4a). In imperatives, these verbs allow the subject to be placed between the off and an (optional) directional PP (4b).

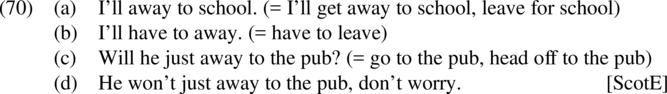

Scottish English also permits a construction where the preposition away can appear without an overt motion verb, in a type of construction which seems familiar from other Germanic varieties or from earlier varieties of English (5). This construction can also be used as an imperative (6), and licenses post-‘verbal’ subjects (7) (see also Henry Reference Henry1995: 58–59, 77, for a similar construction in some Belfast dialects):

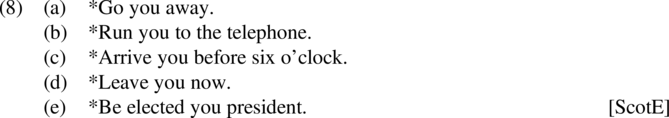

However, these are the only contexts in which postverbal imperative subjects are licensed in the variety of Scottish English under investigation here. In particular, it is not the case that all unaccusative verbs allow postverbal subject placement in imperatives: the below forms, grammatical in Belfast A (1), are ungrammatical in this Scottish variety.

This paper therefore seeks to answer three main questions:

-

(i) If the key factor licensing postverbal imperative subjects in Scottish English is not unaccusativity per se, then what is it?

-

(ii) Given the answer to (i), does this answer indicate a possible revision of Henry’s (Reference Henry1995) analysis of Belfast A, and if so, how should the analysis be revised?

-

(iii) What factor is responsible for the variation between dialects of English concerning the licensing of postverbal imperative subjects, such that Belfast English allows them with a large number of verbs, Scottish English allows them only with a very restricted set of verbs, and standard English does not allow them at all?

In the course of addressing these questions, a fourth question will also be considered:

-

(iv) What is the nature of the Scottish English away construction in which a motion verb can apparently be omitted (I’ll away to school/Away (you) to school!)

The paper will propose that the answer to questions (i)–(iii) above is to be found in the structures assumed for resultative constructions in the relevant dialects, of which goal-PP constructions are assumed to be a subset (following, e.g., Beck & Snyder Reference Beck, Snyder, Do, Domínguez and Johansen2001). Specifically, it is argued that Belfast English has a structure for resultatives involving a syntactically realized (but silent) [cause] feature on a functional head which can assign Case to the subject of the small clause within the resultative. This subject can, by dint of this, remain in situ in imperative constructions, and is not required to move to a preverbal position. By contrast, standard English lacks the functional head which assigns Case to the subject of the small clause, forcing subject movement in order to receive Case. The patterns in the ‘restricted’ (Scottish) variety are argued to result from spell outs of a particular kind of null verb, in conjunction with a [cause]-marked

![]() $ {\mathrm{v}}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

head, which allows for the assignation of Case to the subject of PP small clauses in a very few restricted constructions. In the course of answering the questions in (i)–(iv), the paper therefore also contributes to our understanding of the syntax and semantics of unaccusative and resultative constructions generally and of goal-PP constructions more specifically.

$ {\mathrm{v}}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

head, which allows for the assignation of Case to the subject of PP small clauses in a very few restricted constructions. In the course of answering the questions in (i)–(iv), the paper therefore also contributes to our understanding of the syntax and semantics of unaccusative and resultative constructions generally and of goal-PP constructions more specifically.

Before proceeding, a preliminary note on data. Throughout the paper, I indicate the dialect of English from which an example is drawn (if such a label is lacking, the judgments indicated should be taken to hold across all dialects). All data for Belfast English have been taken from Henry (Reference Henry1995). The main source of the Scottish English data for this paper is my introspective grammaticality judgments.Footnote 3 Unless specifically noted otherwise, the paper refers to this variety simply as ‘Scottish English/ScotE’, to avoid unwieldy repetition of ‘the relevant dialect of Scottish English’. I have not aimed at empirical comprehensiveness with respect to possible dialectal variation within Scotland (or Belfast/Ulster), restricting myself to providing an analysis of the idiolect I myself have access to and making comparison with the Belfast data reported in Henry (Reference Henry1995). However, where I am aware of further dialectal or idiolectal variation I note this, as well as noting places where the proposed analysis is flexible enough to accommodate variation, or where it would predict variation to be ruled out.

2. Comparing Belfast English with Scottish English

2.1. Henry’s original analysis of Belfast A

The basic data Henry (Reference Henry1995) seeks to account for in Belfast A is repeated in (9) from (1).

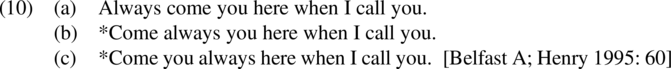

There is evidence that the verb in these structures (and therefore also the subject) is structurally in a very low position. Henry shows, for example, that the verb and subject in Belfast A imperatives obligatorily appear to the right of middle-field adverbs like always.

This indicates that the verb in structures like (10a) has not inverted with the subject, at least not via movement to C (i.e. ‘standard’ subject–auxiliary inversion).Footnote 4 Henry suggests rather that, in Belfast A imperatives, the subject remains in its base-generated position. In the case of unaccusatives or passives, this position will be postverbal, as in (11).

The question then arises as to why unaccusative subjects cannot remain in situ in standard English imperatives.Footnote

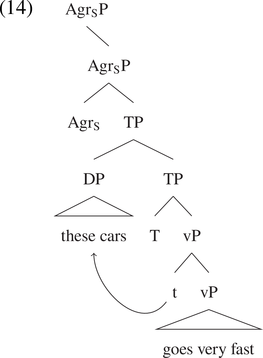

5 Henry argues that this stems from differences between the dialects concerning the positions to which subjects must obligatorily move. Henry assumes a split IP (Pollock Reference Pollock1989) with separate functional projections hosting Tense (TP) and Agreement (AgrSP). Henry further assumes that in standard English (in declaratives), subjects obligatorily move from their vP-internal positionFootnote

6 to [Spec, TP] and ultimately [Spec, Agr

![]() $ {}_{\mathrm{S}} $

P].

$ {}_{\mathrm{S}} $

P].

Henry argues, however, that in Belfast English, AgrS need not prompt movement of the subject to its Spec (at least not in the overt syntax). This is, Henry argues, independently justified given that Belfast English can show a lack of number agreement between subject and verb:

This is taken to be evidence for an optional lack of strong NP features on AgrS, and so the subject can (optionally) raise only as far as [Spec, TP] in Belfast A:

The optionality of movement into [Spec, Agr

![]() $ {}_{\mathrm{S}} $

P] does not alter the word order in declaratives in Belfast A, as the subject still moves out of the vP/VP into [Spec, TP] – above middle-field adverbs, auxiliaries, etc. However, Henry argues that imperatives are not specified for Tense, and so in imperatives, T also bears weak features (alternatively, T is simply not present in imperatives, as proposed by many authors, e.g., Beukema & Coopmans Reference Beukema and Coopmans1989; Zanuttini Reference Zanuttini, Rizzi and Belletti1996; Platzack & Rosengren Reference Platzack and Rosengren1998; Han Reference Han2000). If Agr

$ {}_{\mathrm{S}} $

P] does not alter the word order in declaratives in Belfast A, as the subject still moves out of the vP/VP into [Spec, TP] – above middle-field adverbs, auxiliaries, etc. However, Henry argues that imperatives are not specified for Tense, and so in imperatives, T also bears weak features (alternatively, T is simply not present in imperatives, as proposed by many authors, e.g., Beukema & Coopmans Reference Beukema and Coopmans1989; Zanuttini Reference Zanuttini, Rizzi and Belletti1996; Platzack & Rosengren Reference Platzack and Rosengren1998; Han Reference Han2000). If Agr

![]() $ {}_{\mathrm{S}} $

P has the option of bearing weak features in Belfast English, and TP either has weak features or is not present in imperatives, then the subject is not forced to move to check any features in an imperative clause, and so need not move out of the vP/VP. In the case of a subject which starts as a complement of V – a passive or unaccusative subject – this results in a word order in imperatives where the subject remains in situ, in postverbal position, as shown in (15).

$ {}_{\mathrm{S}} $

P has the option of bearing weak features in Belfast English, and TP either has weak features or is not present in imperatives, then the subject is not forced to move to check any features in an imperative clause, and so need not move out of the vP/VP. In the case of a subject which starts as a complement of V – a passive or unaccusative subject – this results in a word order in imperatives where the subject remains in situ, in postverbal position, as shown in (15).

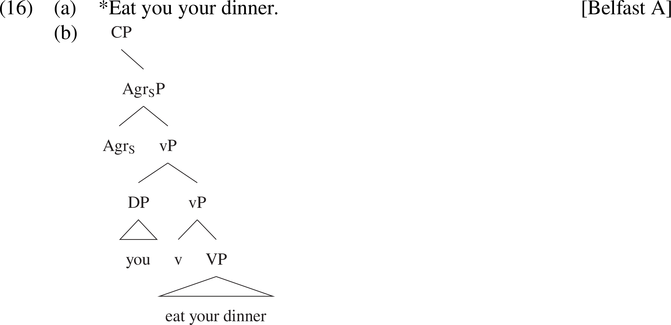

In unergatives or transitives, however, the subject is generated in the specifier of vP; so even if the subject does not undergo movement from its base-generated position, it will still appear preverbally in imperative transitives and unergatives (16).

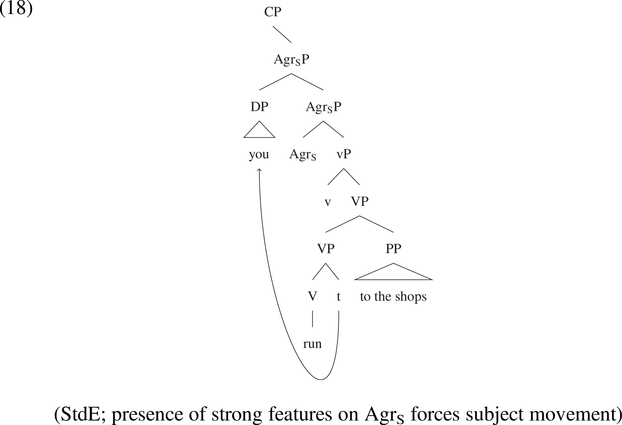

By contrast, in standard English imperatives, even if TP has weak features or is absent from the structure, AgrS is still strong, and still forces subject movement. So in standard English imperatives, subjects (if expressed) will always appear preverbally, i.e. will always move out of vP, even if they are underlyingly complements of V.

2.2 Challenges from Scottish English

This analysis is attractive, particularly insofar as it explains why postverbal subject placement should only be available with unaccusative verbs in Belfast A, and provides a clear locus for the difference between Belfast A and standard English (weak agreement). It is also independently plausible to say that TP does not force subject movement in imperatives (either TP is simply missing in imperatives, or imperative TP lacks an EPP feature that would force its specifier to be filled). And the analysis can be extended, at least in part, to Scottish English; in those cases where postverbal subjects are possible in Scottish English, the verb and subject are also clearly low in the structure (below middle-field adverbs). This is shown below with VP-adjoined just Footnote 7 for get and away; the pattern also extends to the ‘taboo off’ verbs.

However, Henry’s (Reference Henry1995) analysis of Belfast English faces some challenges. One is theory-internal: separate projections for agreement, such as AgrS, were rejected in the turn to Minimalism due to their lack of interpretive import (Chomsky Reference Chomsky1995). If this is accepted, then Henry’s analysis would at least need to be updated, as if AgrS is no longer a separate projection from T – and if the lack of agreement in Belfast English therefore cannot be explained as the lack of strong NP features on AgrS – then the requisite parametric difference between Belfast A and standard English can no longer be stated; that is, it is not clear why Belfast English allows subjects to remain in situ in imperatives (but forces them to move in declaratives), while standard English forces subject movement in all cases.

However, beyond this theory-internal issue, Scottish English provides empirical grounds to doubt that (the lack of) agreement is the key determinant in the licensing of postverbal imperative subjects. There are speakers of Scottish English (in particular dialects spoken in the north-east) who show an agreement pattern similar to the Belfast pattern illustrated in (13), roughly speaking singular agreement with third-person plural non-pronominal subjects (the ‘Northern Subject Rule’; for detail and refinements, see e.g., Smith Reference Smith2000; Pietsch Reference Pietsch2005; Adger & Smith Reference Adger and Smith2010). However, many Scottish English speakers do not accept such sentences – and crucially, there does not appear to be a correlation between acceptance of singular-agreement sentences like (13), and acceptance of low-subject imperatives like Get you to school. My own idiolect, for example, does not accept singular-agreement sentences like the eggs is cracked or the boys gets to school at 9 a.m., but does allow for low-subject imperatives with the subset of verbs enumerated in Section 1.Footnote 8 More crucially, acceptance of singular-agreement sentences does not seem to correlate with acceptance of low-subject imperatives with unaccusatives or motion verbs in general (i.e. forms like go you home). This is surprising if Henry’s account is correct: on the fact of it, Henry’s analysis predicts that systematic singular agreement with plural subjects (i.e. weak features on AgrS) in any dialect of English should allow for postverbal imperative subjects (i.e. a failure of the subject to raise to AgrSP in imperatives).

An anonymous reviewer points out that the above argument could rather be taken as evidence that singular agreement in Belfast and in Scots have different etiologies – and points out that the Northern Subject Rule agreement patterns are not precisely identical to the Belfast patterns (Adger & Smith Reference Adger and Smith2010) – and that it is logically possible for the ‘weak AgrS’ analysis to be correct for Belfast A while some other analysis is correct for Scots. However, as the same reviewer points out, such an approach would require a disunified analysis of both agreement and of low-subject imperatives in Belfast A and in Scots; and postverbal imperatives in Scottish English show enough of a family resemblance with the Belfast pattern to make a unified analysis inviting. In particular, the basic idea that (overt) imperative subjects are forced to raise in standard English, but can (in certain constructions) remain in their base-generated position in Belfast A and in Scottish English, seems like a sound one: those verbs which do allow postverbal subjects in Scottish English are motion verbs, and are plausibly therefore unaccusatives (with postverbal subjects), even if not all unaccusatives allow postverbal subjects in Scottish English. The evidence from verb placement with respect to middle-field adverbs also indicates that postverbal imperative subjects are in a very low position in Scottish English. In what follows, then, I propose a reanalysis of the Belfast data, which I argue can also be extended to account for the more restricted pattern seen in Scottish English, as well as identifying the locus of variation between varieties in terms of which verbs/structures allow postverbal subjects.

3. Belfast English: a reanalysis

3.1. The importance of small clauses

I suggest that it is of key importance that almost all of the Belfast English data adduced by Henry (Reference Henry1995) involve the combination of an unaccusative or passive verb with a complement such as a PP, or in the case of (21c), a resultative small clause.

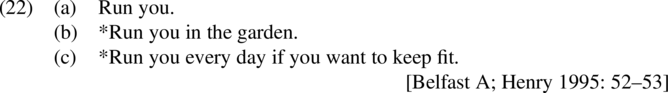

Henry notes that postverbal subjects of motion verbs are, in almost all cases, ungrammatical if a PP is absent, or denotes a location rather than a goal:

The only exceptions are verbs of motion which inherently specify a goal or source, such as arrive and leave, which do not require a directional PP:

Henry interprets this in terms of variable unaccusativity: verbs of motion like run are analyzed as telic – and therefore unaccusative, following work by Angeliek van Hout and others (e.g., Van Hout Reference Van Hout, Alexiadou, Anagnostopoulou and Everaert2004) – when combining with directional PPs, and atelic (and therefore unergative) in other cases. Henry argues that verbs such as run only allow postverbal subjects in their unaccusative frame (that is, a frame in which the subject is underlyingly a direct object of the verb). Verbs like arrive and leave are invariable unaccusatives and so always allow postverbal subjects.

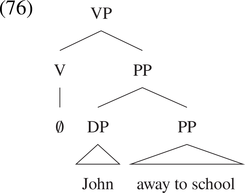

I propose, however, to reanalyze the importance of the PP in these structures. In one prominent family of analyses (Hoekstra & Mulder Reference Hoekstra and Mulder1990; Beck & Snyder Reference Beck, Snyder, Do, Domínguez and Johansen2001; Ramchand & Svenonius Reference Ramchand, Svenonius, Mikkelsen and Potts2002; Svenonius Reference Svenonius2003, Reference Svenonius, Reuland, Bhattacharya and Spathas2007, Reference Svenonius, Cinque and Rizzi2010; Beck Reference Beck2005; Folli & Harley Reference Folli and Harley2006), goal-PP constructions such as He ran to the park have been treated as resultative constructions, where the PP denotes a small clause and contains an external argument; that is, the underlying structure of (24a) is something like (24b).Footnote 9

On such a view, the apparent internal argument of a verb of motion combined with a goal PP would not directly be an argument of the verb. Rather, it is an external argument of the PP shell structure with which the verb combines. Further discussion of and evidence for this analysis will be given below; but if this is indeed the correct analysis of goal-PP constructions, then the generalization about Belfast English may not be that unaccusative subjects (in general) are in an underlying postverbal position in imperatives. It may rather be something like (25).

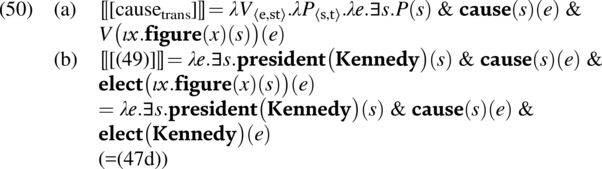

The generalization in (25) is particularly inviting in view of the example Be elected you president, grammatical in Belfast English, but not in standard English, where the subject (if expressed) is forced to raise, resulting in the order You be elected president.

I propose that the generalization in (25) can be implemented in a relatively simple way, by proposing that the grammar of transitive resultative constructions subtly differs between Belfast English and standard English. In Belfast English, a functional head intervenes between verb and small clause, the purpose of which is to semantically encode the causation relation between the two, and which assigns Case to the subject of the small clause. Such subjects therefore do not have to raise for Case in imperatives. In standard English, the feature which encodes this semantic relation is not present on a functional head between verb and small clause, but rather is merged as an affix onto the verb itself – the differing syntactic configuration resulting in different Case assignment possibilities; in standard English, subjects of small clauses must raise to get Case. In the rest of this section, I outline assumptions about the syntax and semantics of resultatives underlying such an analysis of the relevant difference between Belfast English and standard English, before returning to how Scottish English might be analyzed in Section 4.

3.2 The syntax and semantics of resultatives

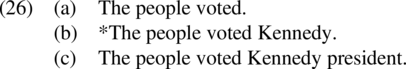

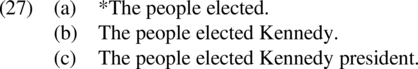

I start by considering intransitive resultatives as in (26), exemplified with the obligatorily intransitive verb vote, and transitive resultatives as in (27), exemplified with the obligatorily transitive verb elect (see Carrier & Randall Reference Carrier and Randall1992).

There are various reasons to believe that, in both (26) and (27), Kennedy president is a small clause, a constituent to the exclusion of the verb (Hoekstra Reference Hoekstra1988; contra Carrier & Randall Reference Carrier and Randall1992). Scope tests, and in particular the interpretation of again (Dowty Reference Dowty1979; Von Stechow Reference Von Stechow1996; Beck Reference Beck2005; among others), have been taken as evidence for this, as in (28).

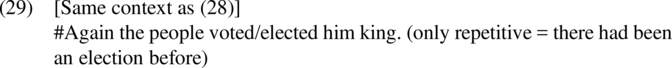

In (28), there had never previously been an election (and note that The people elected him again is a presupposition failure); again is rather modifying the constituent him king, i.e. he is once again king. Crucially, the availability of this restitutive reading tracks the syntactic position of again: it is not available in (29) (Von Stechow Reference Von Stechow1996).

We will focus first on the case of transitive resultatives such as (27c). Even if Kennedy is the subject of a small clause headed by president, it must also be interpreted as the theme of the event of election semantically. (I return to the semantic detail of this claim below.) One way of accomplishing this would be to assume that elect takes both an object (Kennedy) and a small clause with a PRO subject controlled by Kennedy (cf. the ‘Hybrid SC Analysis’ discussed by Carrier & Randall Reference Carrier and Randall1992; Bowers Reference Bowers, Blight and Moosally1997).

However, I assume along with Kratzer (Reference Kratzer, Maienborn and Wöllstein2005: 206) that PRO is not available in structures like (30): ‘the known occurrences of PRO… all occur in environments where a fair amount of functional structure intervenes between it and its antecedent… It includes agreement morphology, which is responsible for establishing the anaphoric relationship between PRO and its antecedent’. There is no such functional structure between Kennedy and PRO in (30). Rather, I assume that Kennedy is indeed the subject of a small clause which is complement of elect – what Carrier & Randall (Reference Carrier and Randall1992) term the ‘Binary SC analysis’.

If this is right, then something has to be done about elect’s obligatory transitivity. There has to be to be some way of relating transitive elect (27b) and the elect that takes a small clause (27c), by (i) reducing the valence of elect to be intransitive, (ii) ensuring that elect’s logical object/theme is identified with the subject of the small clause, and (iii) ensuring that the structure overall will bear a causative/resultative meaning. Here I propose a way of doing this, building on Kratzer’s (Reference Kratzer, Maienborn and Wöllstein2005) analysis of intransitive resultatives, which – as we will see – leads to positive consequences for the (re)analysis of the Belfast A data.

Suppose that the small clause Kennedy president denotes a property of states of Kennedy being president, type

![]() $ \left\langle \mathrm{s},\mathrm{t}\right\rangle $

:

$ \left\langle \mathrm{s},\mathrm{t}\right\rangle $

:

And that the verb elect is underlyingly semantically transitive, that is, it is a relation between an event and a theme (the person elected), type

![]() $ \left\langle \mathrm{e},\mathrm{st}\right\rangle $

(the external/agent argument, the elector, being introduced higher in the clause by a

$ \left\langle \mathrm{e},\mathrm{st}\right\rangle $

(the external/agent argument, the elector, being introduced higher in the clause by a

![]() $ {\mathrm{v}}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

head; Kratzer Reference Kratzer, Rooryck and Zaring1996).

$ {\mathrm{v}}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

head; Kratzer Reference Kratzer, Rooryck and Zaring1996).

The verb elect can combine with an argument like Kennedy, as in (33c), but it is not of the correct semantic type to combine with the small clause Kennedy president. Footnote 10 Something is needed to resolve this type of mismatch. The property of states in (32) could be shifted by the application of the function in (34), for example (an adaptation of a similar proposal in Kratzer Reference Kratzer, Maienborn and Wöllstein2005: 195–196).

In (34), cause is a relation between events

![]() $ e $

and states

$ e $

and states

![]() $ s $

such that

$ s $

such that

![]() $ e $

directly causes

$ e $

directly causes

![]() $ s $

, that is (roughly) that

$ s $

, that is (roughly) that

![]() $ s $

is an end-state of

$ s $

is an end-state of

![]() $ e $

and if

$ e $

and if

![]() $ e $

had not happened,

$ e $

had not happened,

![]() $ s $

would not hold (following Lewis Reference Lewis1973; Kratzer Reference Kratzer, Maienborn and Wöllstein2005); and figure is a relation between states

$ s $

would not hold (following Lewis Reference Lewis1973; Kratzer Reference Kratzer, Maienborn and Wöllstein2005); and figure is a relation between states

![]() $ s $

and individuals

$ s $

and individuals

![]() $ x $

such that

$ x $

such that

![]() $ x $

is the figure (as opposed to Ground) of

$ x $

is the figure (as opposed to Ground) of

![]() $ s $

, the salient or foregrounded entity in

$ s $

, the salient or foregrounded entity in

![]() $ s $

(cf. Talmy Reference Talmy and Greenberg1978); ‘

$ s $

(cf. Talmy Reference Talmy and Greenberg1978); ‘

![]() $ \iota x.\mathbf{figure}(x)(s) $

’ denotes the foregrounded entity in

$ \iota x.\mathbf{figure}(x)(s) $

’ denotes the foregrounded entity in

![]() $ s $

.

$ s $

.

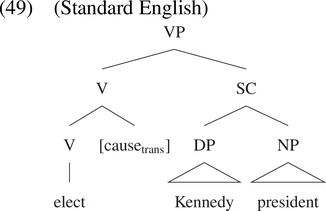

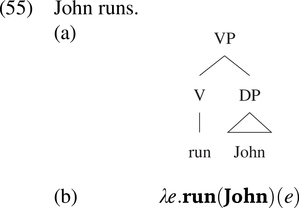

The effect of the shift in (34) is to saturate the internal argument of a transitive verb, identifying it with the ‘figure’ of the small clause, and to introduce a causative relation between the event denoted by the verb and the state denoted by the small clause. This can be seen more concretely by stepping through how (34) would apply in (31). The shift would apply between the verb elect and the small clause Kennedy president, applying first to Kennedy president:

The function in (35) then in turn takes the transitive verb, here elect, as its argument:

The result is a predicate of events (i.e. the type of a intransitive verb). Those events are such that they cause a state

![]() $ s $

of which

$ s $

of which

![]() $ P $

holds (in this case, a state in which Kennedy is president), and they are events of electing the figure of this resultant state. In (36), the figure of the end-state caused by an event of election, in which state Kennedy is president, is picked out; it is reasonable to assume that the ‘figure’ in all such states is Kennedy himself. In this way, the ‘figure’ of the small clause can be identified with the theme of the event of election.

$ P $

holds (in this case, a state in which Kennedy is president), and they are events of electing the figure of this resultant state. In (36), the figure of the end-state caused by an event of election, in which state Kennedy is president, is picked out; it is reasonable to assume that the ‘figure’ in all such states is Kennedy himself. In this way, the ‘figure’ of the small clause can be identified with the theme of the event of election.

The shift in (34), when applied to a small clause and a verb, then does what was required: it introduces a causal relation between the event denoted by the verb and the state denoted by the small clause, and it reduces the valency of the verb, saturating its internal argument and identifying it with the figure of the state denoted by the small clause (the end-state of the causal event).

Note that this shift, and in particular the identification of the subject of the small clause with the thematic object of the verb, leads to a slightly different outcome from Kratzer’s (Reference Kratzer, Maienborn and Wöllstein2005) treatment of intransitive resultatives like (37).

In such a case, the apparent object (the teapot) is clearly not semantically an argument of the verb (Hoekstra Reference Hoekstra1988; Kratzer Reference Kratzer, Maienborn and Wöllstein2005), as it is not the teapot which is drunk (which is even clearer in examples like John drank the pub dry). Kratzer proposes that drink is basically intransitive (38a), and that the small clause (which denotes the state of the teapot being dry, (38b)) is shifted (38c) without saturating any internal argument of the verb, leading to the denotation in (38d).

The verb drink can then combine with (38d) intersectively to deliver (39):

If the above proposals are on the right track, this predicts a difference between resultatives built on basically intransitive verbs such as drink and those built on obligatorily transitive verbs such as elect: the former do not, but the latter do identify the subject of the small clause with the theme of the event. This is a welcome conclusion already for the case of drink the teapot dry, where one does not want to identify the teapot as the theme of the drinking. It is also a welcome conclusion for transitive verbs like elect. Consider the below contrast between obligatorily intransitive vote and obligatorily transitive elect.

The interpretations of (41) are unsurprising on the treatments given above: there is an event of voting (respectively election) which causes Kennedy to be president/in the White House, and in (41b), Kennedy – the figure of the resultant state in which he is president – is the theme/patient of the election. What happens with (42), by contrast? The denotations of the verb phrases (that is, ignoring the subject/agent the people) in these cases are as below, applying the semantic rules above.

Nothing is deviant about (43a); a voting event could easily cause a state in which Carter is on the dole queue. However, (43b) describes events which have as their end-state Carter being on the dole queue and in which the figure of this end-state (Carter) was the theme of the election. Given this contradiction – the themes of events of election are the winners, not the losers – (42b) comes out contradictory/deviant.Footnote 11

3.3. Encoding causation in syntax – in Belfast English and standard English

Suppose that shifts such as those discussed above are available and mediate between verbs and small clauses in resultative constructions. How are these shifts encoded in grammar? One option is to assume that there are special rules of semantic composition, or type-shifting, which apply to structures like (31), where a verb composes with a predicate of states. Such a rule, for example, is proposed by Von Stechow (Reference Von Stechow, Egli, Pause, Schwarze, von Stechow and Wienold1995) for resultatives under the name of ‘Principle R’, further extended by Beck & Snyder (Reference Beck, Snyder, Do, Domínguez and Johansen2001) to goal-PP constructions. An alternative, explored by Kratzer (Reference Kratzer, Maienborn and Wöllstein2005) and which I would like to adopt here, is that the shift is represented directly in the syntax, by means of a (possibly silent) head or feature with an appropriate semantics. Kratzer (Reference Kratzer, Maienborn and Wöllstein2005) proposes that, in resultative constructions with intransitive verbs, an affixal morpheme [cause] appears atop the small clause (44). This morpheme has the semantics in (45a); it shifts the stative denotation of the SC (38b) into a predicate of events of causing such states to come about (45b).

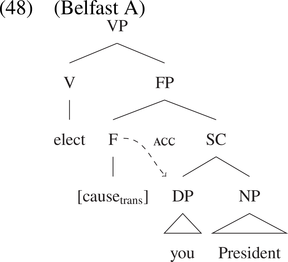

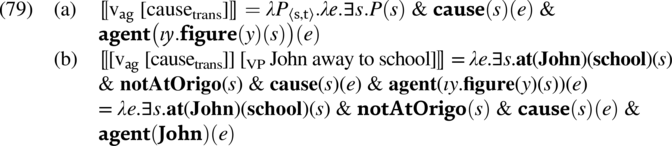

Suppose that the shift that I have proposed for transitive verbs can be encoded in a similar way, on a morpheme/feature – call it [causetrans] – which mediates between transitive verbs and small clauses.

Suppose now too that this [causetrans] feature is, or can be, introduced on a functional head which is capable of assigning accusative Case downwards to the subject of the small clause.

If this is possible, at least in Belfast English, then we can explain why the word order Be elected you President is grammatical in imperatives in Belfast English. The subjects in such structures – actually the arguments of the embedded small clauses, not on this view (syntactic) arguments of the verb – must raise in declaratives to satisfy the EPP (You were elected President), but in imperatives, where the EPP is by hypothesis not active, the subject need not raise, even for Case, as it has its Case needs satisfied by the functional head which hosts [causetrans].

What is the difference with standard English? I propose that, in standard English, the [causetrans] feature is merged, not as a head above the small clause, but rather directly onto V. This requires a reversal in the order of the arguments of [causetrans], but otherwise, composition can proceed unproblematically.

However, this structure does not contain any functional head assigning Case to the subject of the small clause Kennedy. In a passive structure, there is no other source for Case within the extended verbal projection either:

In structures like (51) in standard English, then, the subject of the small clause will have to raise for Case. In declaratives, this would be to [Spec, TP] (Kennedy was elected president). Given the grammaticality (in all Englishes) of overt-subject imperatives where the subject is preverbal (you be elected president, everybody eat their dinner, etc.), I assume that there is some preverbal functional projection also in imperatives to which the subject can move and receive Case. I remain agnostic here about what this projection is; it could be T, as in declaratives, and as Zanuttini, Pak & Portner (Reference Zanuttini, Pak and Portner2012) suggest (cf. Rupp Reference Rupp and van der Wurff2007 on IP in imperatives; pace Henry Reference Henry1995 and the references cited in Section 2 for the lack of TP in imperatives); if so, it would have to be a T exceptionally lacking the EPP-property which forces subject movement (as we do not want subject movement to this high position to be forced in Belfast A imperatives). To remain neutral on the matter here, I show this projection as FP in (52). This movement is optional in Belfast A, because the subject of the small clause can get Case in situ from the functional head hosting [causetrans] as in (48); but in standard English, the requirements of the Case Filter force overt imperative subjects to raise to this higher position.Footnote 12

3.4. Goal-PP constructions and resultatives

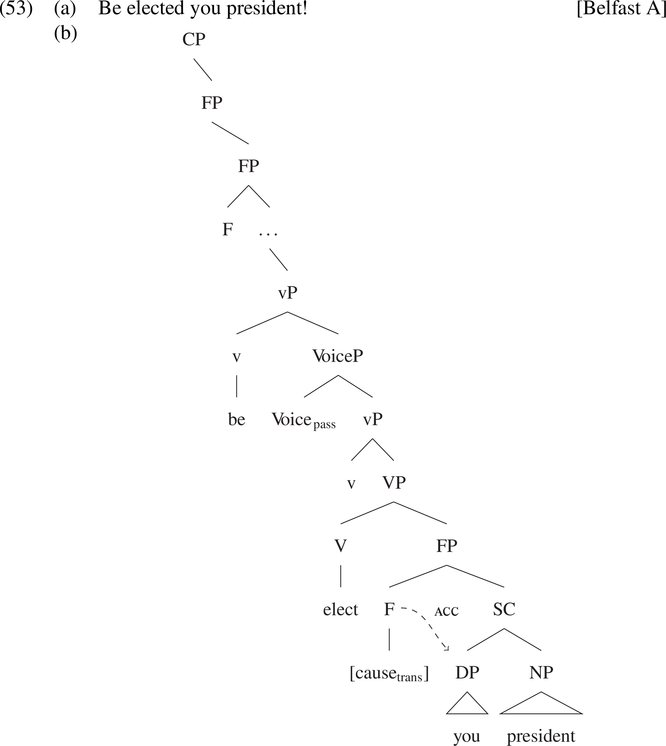

Let us now return to verbs of motion. Suppose that these are always ‘basically’ unaccusative, that is, that they take an internal argument; they are the same semantic type as transitive verbs, but have no external argument introduced by a v head.

Simple cases, with no PP, have the structure in (55a) and the interpretation in (55b).

As discussed above, many authors have argued that verbs of motion with goal-PP constructions are in fact resultative constructions, where the PP denotes something like a small clause. One important argument in favor of this treatment is again the behavior of again. With transitive verbs involving an (apparent) object and a goal PP, it is clear that again can take scope over a stative component alone (i.e. a restitutive reading):

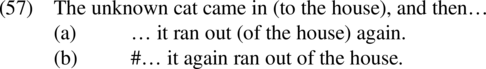

In (56a), again must be taking semantic scope only over the cat out (as there hasn’t been a previous throwing event). As before, this is sensitive to syntactic placement; the restitutive reading goes away in (56b). Beck (Reference Beck2005) notes that this is true also for intransitive goal-PP constructions.

This suggests that, at some syntactic level, there is a constituent the cat out of the house which is being modified by again in (57a) (but not in (57b), where again takes scope over the whole verb phrase including ran).

To capture this, we can give verbs like run the same treatment as reviewed above for transitive verbs like elect. The valency-reducing causative shift can mediate between a PP small clause John to the park and the verb.

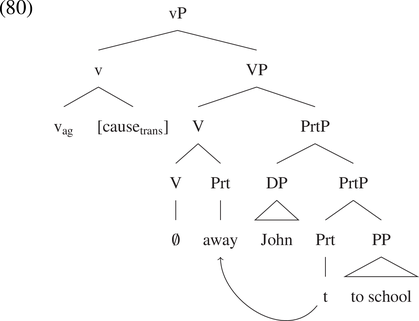

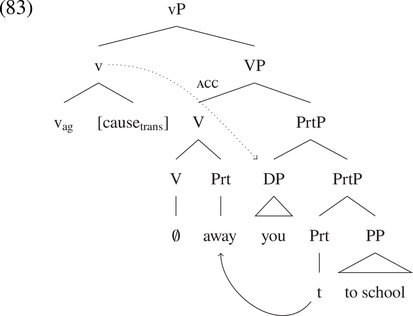

If this is right, then we capture the differing behavior of goal-PP constructions in imperatives in Belfast A and in standard English in the same way as above for passive transitive resultatives such as elect X president: [causetrans] is merged in a functional head above the small clause in Belfast A, but merged directly onto the verb in standard English, leading to a difference in Case assignment possibilities. Apparent subjects – not syntactic arguments of the verb, but rather subjects of the PP small clause – can remain in situ in Belfast A, (60), as they can receive Case from [causetrans]; but they must raise in standard English to receive Case.

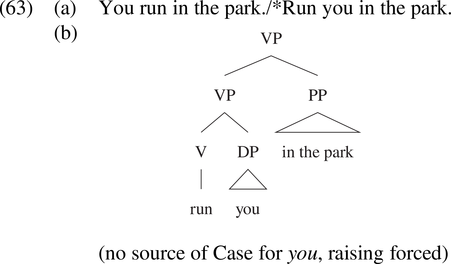

Note that this analysis correctly rules out postverbal imperative subjects even in Belfast A without a goal-PP or other small clause. In (62), there is no small clause (and no [causetrans]) to assign Case; while in (63), the locative PP does not denote a resultant state of the running, and so would not be composed with the verb via [causetrans] (plausibly simply being an adjunct to VP).

The cases left to consider are verbs like arrive and leave, which have directionality ‘built in’ to them, and which allow postverbal subjects in Belfast A:

The verbs arrive and leave do not combine with goal PPs (but rather only locative ones: arrive at the party, *arrive to the party). However, such verbs have in fact been argued by Moro (Reference Moro1997) and Hale & Keyser (Reference Hale and Keyser2000) to combine with a small clause, a covert PP.

The covert there/away which I indicate in (65) may be an instantiation of Kayne’s (Reference Kayne, Maschi, Penello and Rizzolatti2007) abstract PLACE (see also Collins Reference Collins2007). Moro (Reference Moro1997) proposes the syntax in (65) as an explanation for the grammaticality of there-insertion with verbs like arrive (There arrived many students); there is an overt realization of the covert PP, which can raise to subject position. Note also the similar behavior of again in being able to take scope over the resultant state alone (i.e. a restitutive reading) – and the sensitivity to syntactic placement:

If arrive and leave introduce their subjects in (covert) PPs, the above behavior can be understood in terms of the constituent that again modifies.

If this analysis of arrive and leave is correct, then this allows for the same treatment of postverbal imperative subjects as internal to a PP, and receiving Case from a functional head bearing [causetrans].

3.5 Interim summary

I have so far proposed that the distinction between Belfast English and standard English is not a general one concerning the movement of subjects, but rather concerns a difference in the structure of resultative constructions (including goal-PP constructions), and a concomitant difference in Case licensing between the two varieties. This proposal assumes that the (semantic) arguments of verbs like run can either be introduced as complements of the verb, or as the external argument of a PP.Footnote 14

The reader might wonder if there is a simpler possibility for encoding the difference between standard and Belfast Englishes on this account: rather than suggesting a different geometry for resultative constructions (i.e. a different position for [causetrans]), might it rather simply be the case that F (the functional head bearing [causetrans]) can assign Case in Belfast English but not in standard English? This would be an ‘uninteresting’ stipulation, but the position of [causetrans] is also a stipulation. I argue, however, that locating the difference in the position (and order of application of arguments) of [causetrans] allows the analysis to naturally extend to capture the more restricted patterns of postverbal imperative subjects seen in Scottish English. The remainder of the paper takes up the task of showing this.

4. Scottish English in more detail

Recall that, in Scottish English, some – but very few – verbs allowed postverbal subjects in imperatives.

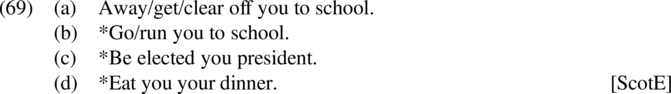

The example in (69d), with the transitive verb eat, is ruled out presumably because the subject (as an external argument) is always structurally superior to the verb. However, if the subject in (69b, c) is underlyingly the subject of a resultative small clause/PP, then this suggests that this subject cannot receive Case in (69b, c) in Scottish English. If the analysis presented in the previous section is on the right track, this suggests that the general structure of (transitive) resultatives (including goal-PP constructions) in Scottish English involves merging [causetrans] onto the verb, not as a separate head above the small clause which can assign Case to its subject. That is, Scottish English (like standard English, and unlike Belfast A) only has the version of [causetrans] which combines, first, with the transitive verb (the relation between entities and events) and, second, with the small clause (the property of states). But what then is the explanation for the postverbal subject placement in (69a)? I propose that the key clue is to be found in a detailed examination of the apparently ‘verbless’ case with away.

4.1. Away

‘Verbless’ away is quite generally available in contexts where a bare verb can appear (the ‘bare stem condition’ of Carden & Pesetsky Reference Carden, Pesetsky, Beach, Fox and Philosoph1977).Footnote 15

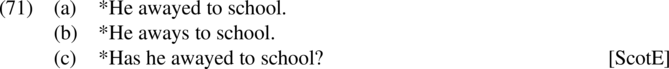

It cannot, however, appear in contexts where it would have to bear inflection. The examples in (71) are ungrammatical:

And verbless away is most widely accepted in construction with ‘filled T’, i.e. in construction with an auxiliary (other than have):

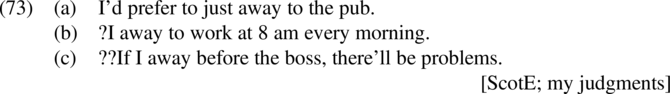

My own idiolect accepts the construction in infinitival contexts (73a), but only very marginally in uninflected finite contexts lacking an auxiliary or modal (73b, c); an anonymous reviewer, and Gary Thoms (p.c.; from the west of Scotland), report that all of the forms in (73) are more severely degraded or ungrammatical for them.

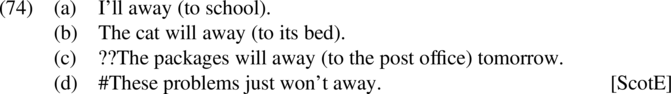

Importantly, the construction requires a volitional or animate subject; (74a, b) are acceptable, but (74c) is degraded, and (74d) is impossible (and contrasts with the fully acceptable These problems just won’t go away).

This distinguishes this Scottish English case from the general case of null motion verbs familiar from Germanic (75), which can (75a) but need not (75b, c, d) have animate/volitional subjects.

This agency restriction provides, I believe, the key to the analysis of these structures. Suppose that Scottish English (but not standard English) has in its lexicon a null verb, similar to the null motion verbs in Germanic more generally (see e.g., Van Riemsdijk Reference Van Riemsdijk2002), and like these null verbs in Germanic obligatorily selecting for a goal PP, but without any semantics of its own; it is a simple identity function, passing up the value of the goal PP it takes as complement.Footnote 16

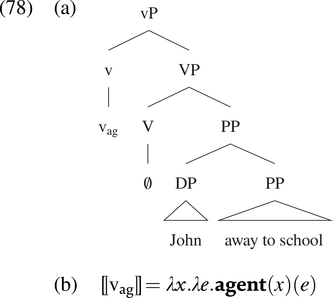

Now suppose that the little v head

![]() $ {\mathrm{v}}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

which introduces external arguments, agents (Kratzer Reference Kratzer, Rooryck and Zaring1996), is merged above this structure.

$ {\mathrm{v}}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

which introduces external arguments, agents (Kratzer Reference Kratzer, Rooryck and Zaring1996), is merged above this structure.

The denotation in (78b) and that in (77b) cannot combine as they are – but they are the right types for combination by [causetrans]. The types are the same as an unaccusative or transitive verb combining with a small clause, exactly the case we have been considering. What is the result if we let [causetrans] – the standard English version which combines first with the verb – merge with little v in this structure? Semantically, the result is as below:

The v

![]() $ {}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

head in (79a) has been changed to the right type to combine with the small clause – and it has also had its valency reduced, so it will no longer semantically introduce an agent in its specifier. The agent is rather identified with the subject of the small clause. In (79b), we see the result of the whole composition: a description of events of John (agentively) causing John to be at school (which is not near the origo/reference point, i.e. it is ‘away’). This is a fairly good paraphrase of the desired truth conditions. In particular, the fact that v

$ {}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

head in (79a) has been changed to the right type to combine with the small clause – and it has also had its valency reduced, so it will no longer semantically introduce an agent in its specifier. The agent is rather identified with the subject of the small clause. In (79b), we see the result of the whole composition: a description of events of John (agentively) causing John to be at school (which is not near the origo/reference point, i.e. it is ‘away’). This is a fairly good paraphrase of the desired truth conditions. In particular, the fact that v

![]() $ {}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

has an agentive semantics means that the structure in (79) will be incompatible with non-agentive arguments, capturing the pattern in (74).

$ {}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

has an agentive semantics means that the structure in (79) will be incompatible with non-agentive arguments, capturing the pattern in (74).

Suppose further that the particle away raises to adjoin to V (see Svenonius Reference Svenonius, Black and McCloskey1992).

We can then suppose that – in the declarative case – TP is merged above this vP, and the EPP prompts movement of the subject (here John) to [Spec, TP].

We are now in a position to return to post-‘verbal’ imperative subjects with away:

The key point here is that, on the present analysis, these structures contain v

![]() $ {}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

, the head which standardly introduces external arguments and which assigns Case to objects. Even though this head has semantically had its valency reduced (has had its argument saturated), we might suggest that its ability to assign Case remains. As such, it can assign Case downwards to the subject within the PP/small clause.

$ {}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

, the head which standardly introduces external arguments and which assigns Case to objects. Even though this head has semantically had its valency reduced (has had its argument saturated), we might suggest that its ability to assign Case remains. As such, it can assign Case downwards to the subject within the PP/small clause.

The crucial difference between Scottish English and standard English on this account is not in the [causetrans] feature (as proposed for Belfast A), but rather the existence in Scottish English of a null verb, with no semantics of its own, which can combine with a goal PP.

Some comment is required on the distribution of this null V. As discussed above, away-constructions generally require a ‘filled T’. This again seems familiar from the ‘standard’ Germanic case, when compared, e.g., with the proposal by Van Riemsdijk (Reference Van Riemsdijk2002) that ellipsis of go is licensed by modals. However, not only modals but also forms of do (in negation or question contexts) permit away in Scottish English. A simple explanation for the distribution of away/the null V may be that neither the null V, nor away, can morphologically host tense/agreement or aspectual morphology (i.e. forms like awayed or aways are not possible).Footnote 17 Without a host for this morphology, it will be impossible to use away in finite contexts, or as a perfect participle, as this would violate the Stranded Affix Filter (Lasnik Reference Lasnik, Hornstein and Lightfoot1981).Footnote 18 If there would in any case be no overt agreement (first/second person or plural subjects in simple present), the result is degraded but not fully ungrammatical (in my judgment; as noted above, others reject these more strongly):

The degradation seems to be an effect (for which I do not have an explanation) of the habitual meaning of the simple present, as these sentences are similarly degraded in question forms with do:Footnote 19

Speakers vary in their acceptance of infinitival complements like (86):

(86) %I told the children to away to their beds.

I do not have a full explanation for this, but speculate that the variation may have something to do with how the different idiolects treat the morphophonological properties of infinitival to (cf., for example, the variation in judgments in whether/in what configurations to licenses VP Ellipsis discussed by Johnson Reference Johnson, Baltin and Collins2001).

The null verb seems to be restricted to selecting PPs headed by away in the author’s idiolect, as the structures in (87) are ungrammatical in that idiolect.

This can potentially be treated as a restriction on spellout (anticipating the discussion of get below). The spellout of the verb as zero may be dependent on a form of formal licensing, the incorporation of the particle into the null V.Footnote 20 In the idiolect under investigation here, only away can perform this function, but there is a certain amount of dialectal/idiolectal variation. An anonymous reviewer states that they accept (87b) with off, and the example in (88) with along is attested:

And a few examples can be found online which seem to lack a particle, consisting solely of a directional PP headed by to (in its dialectal form tae in (89)), although these are rare.

The existence of forms like (89) suggests that, for some Scottish English speakers, the null motion verb does not need to be licensed via incorporation of a particle.

4.2. Get

The analysis above can now be extended to postverbal subjects with get.

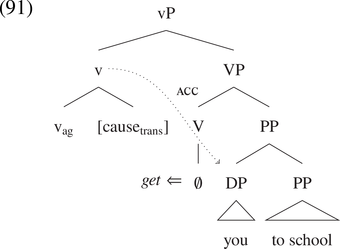

This can be treated as the spellout of the null motion verbFootnote 21 in the case where no particle raises to adjoin to it. The structure of (90) would then be as in (91) below.Footnote 22

This is not quite the same get as appears in motion constructions in standard English (92), both for reasons internal to the analysis – the null, ‘semanticsless’ motion verb in (91) is hypothesized to not be available in standard English – and also because the ‘standard’ get can be non-agentive (92b); the get in (91) requires the presence of ([causetrans]-marked) v

![]() $ {}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

for its interpretation, which should force an agentive interpretation.

$ {}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

for its interpretation, which should force an agentive interpretation.

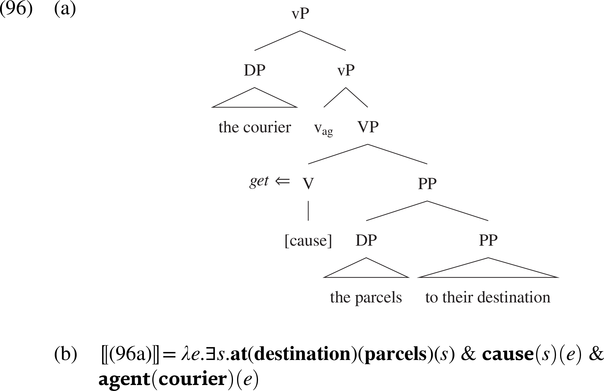

We can perhaps rather analyze the get in (92) as the spellout of a V head with the semantics of [cause] (NB not [causetrans], but rather the ‘intransitive’ variant of [cause] described in (45a)).

No agentive semantics is implied in (94), as desired. Separating this get from the get which allows postverbal subjects in Scottish English also accounts for the fact that the ‘standard’ get (in (92)) can itself be causativized – that is, it can have an additional external argument, as in (95).

On the current analysis, this can be captured by merging a v

![]() $ {}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

head above the VPs in (93) (see Alexiadou, Anagnostopoulou & Schäfer Reference Alexiadou, Anagnostopoulou, Schäfer and Frascarelli2006).

$ {}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

head above the VPs in (93) (see Alexiadou, Anagnostopoulou & Schäfer Reference Alexiadou, Anagnostopoulou, Schäfer and Frascarelli2006).

Such causativization can also be reflexive, as in (97).

Importantly, causativization is not possible with motion away. Footnote 23

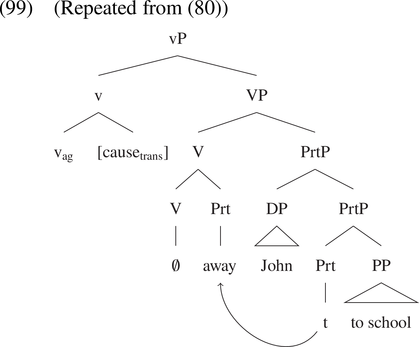

That can be understood if away has the v

![]() $ {}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

+[causetrans] structure suggested in Section 4.1; the structure in (99) can be built, but on the assumption that only one v

$ {}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

+[causetrans] structure suggested in Section 4.1; the structure in (99) can be built, but on the assumption that only one v

![]() $ {}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

can be present in any one clause, it would not be possible to introduce another external argument (and semantically no external argument can be introduced in the specifier of v

$ {}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

can be present in any one clause, it would not be possible to introduce another external argument (and semantically no external argument can be introduced in the specifier of v

![]() $ {}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

in (99), as it has been ‘detransitivized’ by [causetrans]).

$ {}_{\mathrm{ag}} $

in (99), as it has been ‘detransitivized’ by [causetrans]).

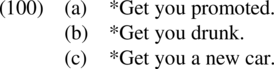

Distinguishing the two gets also gives us a handle on why it is only motion get which allows for a postverbal subject in Scottish English. The below are not grammatical, at least in the author’s idiolect.

The get in (100a, b) is plausibly the same get as in (92) (the possession get in (100c) presumably being something different again). Importantly, there is no external argument, and therefore no vag, in such structures (when only one argument is present).

There would therefore be no source of Case for the postverbal subjects in (101), and such structures are therefore ruled out, given the additional stipulation that Scottish English (like other Germanic languages) allows the null verb to combine only with a goal PP.Footnote 24

4.3 Taboo off verbs

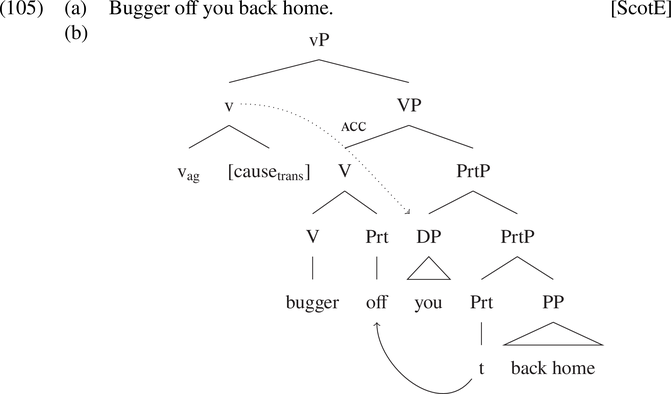

A similar analysis can be given to the ‘taboo off’ verbs:

With the possible partial exception of clear, none of the verbs that appear in (102) have the meaning that they do outside of this construction. Rather, all the verbs in (102) seem to have very little meaning of their own besides an expressive dimension (i.e. they are ‘taboo’). Given this, I suggest that is plausible that these verbs (in Scottish English) also have the truth-conditional semantics of an identity function, as with the null motion verb above. For simplicity, I show their expressive component as a presupposition (between the lambdas in (103) and the output, a condition on well-definedness), though in a fuller treatment, this would presumably be encoded as something like a conventional implicature (see Potts Reference Potts2005). These select PrtPs headed by off (prompting raising of off to the verbFootnote 25), and pass up the meaning of these PrtPs (i.e. properties of states).

As such, these VPs can also be taken as complement by a [causetrans]-modified vag; and as before, this allows for Case assignation to the subject of the PrtP in its underlying position in imperatives.

As with get, this correctly predicts that these verbs cannot be causativized (although see Footnote 27):Footnote 26

I assume that Englishes in which postverbal subjects are not permitted with taboo off verbs treat them as ‘normal’ motion verbs, i.e. where the verb itself introduces an event argument and is modified by [causetrans]. The absence of vag in such structures means that the subject of the PP will have to raise for Case.Footnote 27

4.4 Loose ends: mere and mon

This subsection notes for completeness two other instances of apparently the same pattern, with reduced forms of come here and come on.

Such forms seem to more-or-less transparently result from incorporation of the particles here and on into a heavily reduced form of the verb come. Some speakers (although not this author) also have a form gon, transparently ‘go on’.Footnote 28

These forms could potentially be given a similar analysis to the taboo off verbs, with the (c)’m- and g- components being contributed by V and the particles raising to incorporate.

(110)

However the mere/mon forms seem to be restricted to imperatives; the following are not very natural (note that away has a similar restriction in Belfast English; see Footnote 15; see also Henry Reference Henry1995: 58–59, 77).

And in the relevant dialects which have gon, this also has a use as an exhortative particle in imperatives – see also McCloskey (Reference McCloskey and Haegeman1997) on a similar particle in Ulster English and Weir (Reference Weir, Cruickshank and Millar2013) and Sailor & Thoms (Reference Sailor and Thoms2019) on the similar particle gonnae in Scottish English:

Given the restriction to imperatives, these forms may be amenable to an alternative analysis; e.g., as being generated in or moved to C (see Weir Reference Weir, Cruickshank and Millar2013; Sailor & Thoms Reference Sailor and Thoms2019). As the facts here are somewhat less clear, the above data are included for completeness, but detailed analysis is left to future work.

5. Conclusion

The analysis laid out in this paper has aimed to capture the variation we see between standard, Belfast, and Scottish Englishes in a grammatically constrained way. Beyond simply capturing the data and the variation between dialects and speakers, the analysis presented here raises questions of wider theoretical import. If the analysis presented here is on the right track, it provides support for a view of goal-PP constructions in which they introduce their own external argument, as in Beck & Snyder (Reference Beck, Snyder, Do, Domínguez and Johansen2001) and Beck (Reference Beck2005), among others. Moreover, given that this external argument appears to be realized in situ in postverbal imperatives in Belfast and Scottish Englishes, this suggests (as suggested in Footnote 9) that goal-PP constructions are (or at least can be) raising constructions, rather than control structures in which the external argument is PRO, as proposed by previous authors.

Many avenues for further exploration remain. This exploration has focused on a limited set of data, i.e. the data reported in Henry (Reference Henry1995) for Belfast English, and a restricted set of Scottish English idiolects. The empirical picture is likely to be considerably richer than this suggests – as Henry’s (Reference Henry1995) pioneering work already demonstrated, by showing the distinction between ‘Belfast A’ and ‘Belfast B’. Given the close historical and geographical relationship between Belfast English(es) and Scottish English(es), diachronic and/or detailed microcomparative work on (the relation between) these varieties is likely to be fruitful. In addition, diachronic studies of the null verb construction in English, and of (motion) get with apparent postverbal argument (of the get thee to a nunnery type, cf. Footnotes 2 and 22), may shed light on the development of the Scottish and Belfast patterns, and the extent to which specifically get is ‘special’, as implied by the data and analysis in this paper.