Impact statement

Coastal tourism is often seen as an important part of an economic development strategy. However, most highly cited papers suggest that economic benefits are unequally distributed between tourism investors and resident communities. The highly cited papers also often reflected negative local environmental and social impacts. Furthermore, some global sector reviews describe the tourism enterprise as a guise for property development and investment speculation, without a long-term commitment to local peoples or place. The changing nature of the global tourism enterprise has implications for the way that tourism is examined (historically focused on local impacts from specific tourism operations) and for how tourism is considered within the context of integrated coastal zone management and sustainable development.

Introduction

Many economic development strategies for coastal regions throughout the world include tourism as part of the solution (Becker, Reference Becker2013; Fahimi et al., Reference Fahimi, Saint Akadiri, Seraj and Akadiri2018; Faber and Gaubert, Reference Faber and Gaubert2019). These strategies place tourism as a potential panacea to the improvement of national and regional economies, through to sustainable livelihoods at the community scale (Cortés-Jiménez, Reference Cortés-Jiménez2008; Zhao, Reference Zhao2020). However, these strategies are not based on a holistic understanding of the impacts of tourism on social, cultural, economic or environmental domains. Instead, they tend to focus on short-term inputs of capital in the form of land development and projections of tourist expenditure, which may appear in national accounts of GDP but are unlikely to benefit local communities in the long term (Lange, Reference Lange2015; Martasuganda et al., Reference Martasuganda, Tjahjono, Yulianda, Purba and Faizal2020). In 2012, Buckley identified that the ‘[tourism] industry is not yet close to sustainability’ (p. 528) based on an evaluation of the tourism contributions to sustainable development. As coastal regions continue to be exposed to multiple threats such as climate change, resource degradation and urbanisation (Nunn et al., Reference Nunn, Smith and Elrick-Barr2021), the mechanisms for achieving sustainable development and building social-ecological resilience are ever more important. Following the work of Buckley (Reference Buckley2012) and others, this paper takes a critical view of the role of tourism in achieving these aims and contributes to a better understanding of the impacts of tourism on coastal social-ecological systems.

Methods

To examine the role of tourism in achieving sustainable development and resilience in coastal areas, the impacts of tourism on society, economy and environment were explored through an analysis of highly cited literature. The Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus databases were searched using the search string ‘touris*’ AND ‘coast*’ in title, abstract, keywords (Scopus) or TOPIC (WoS), with no date limitation. The results were ordered by number of citations, with top 100 cited journal papers from each database exported for review. The top 100 cited papers from Scopus ranged from 152 to 3,688 citations. The top 100 cited papers from WoS ranged from 163 and 3,607 citations.

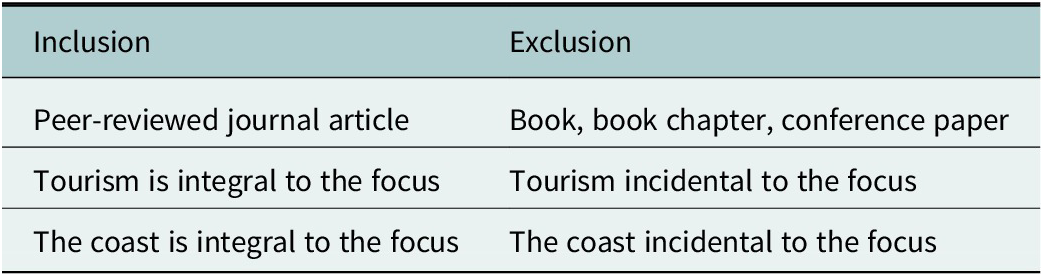

In addition, WoS ‘highly cited’ (WoSHC) journal papers (i.e. papers that perform in the top 1% based on the number of citations when compared to other papers published in the same field in the same year) were included in the review to ensure highly cited papers were not biased by date of publication. The WoSHC papers were published between 2011 and 2021 and cited between 8 and 871 times. The three exports (top 100 Scopus, top 100 from WoS, 60 WoSHC) were combined and duplicates were removed, leaving 164 unique papers for review. Title and abstracts were reviewed, and inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied (Table 1). Seventy-two highly cited papers addressing aspects of tourism in coastal areas remained.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for highly cited paper selection

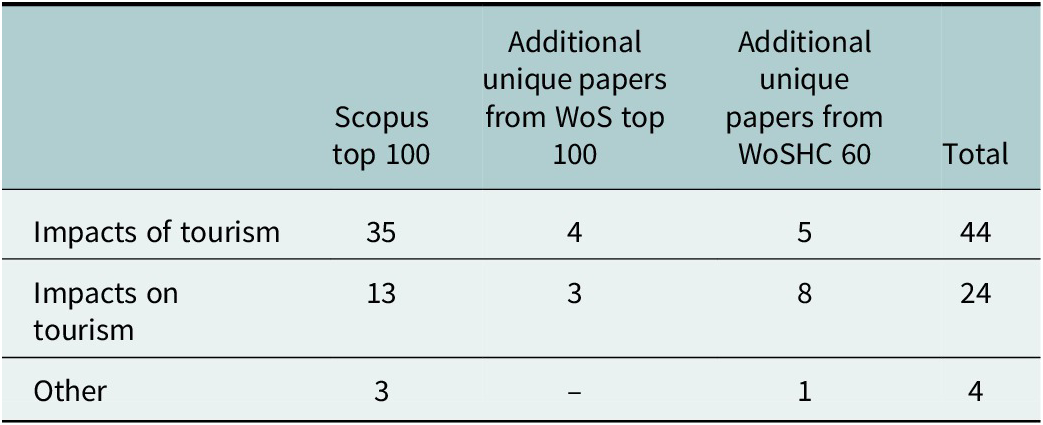

Our analysis focused on understanding whether tourism has a positive or negative impact on coastal social-ecological systems. The literature was therefore screened to distinguish between papers that focused on the impacts of tourism on social-ecological systems (e.g. the contribution of tourism to plastic pollution in coastal areas) versus those that addressed socio-ecological impacts on tourism (e.g. the impacts of climate change on tourist visitation levels). Forty-four papers focussed on the impacts of tourism, 24 on the impacts on tourism, with four papers not addressing either (e.g. generating a profile of tourists or developing indicators of sustainable tourism) (Table 2).

Table 2. Categorisation of the 72 highly cited papers addressing coastal tourism

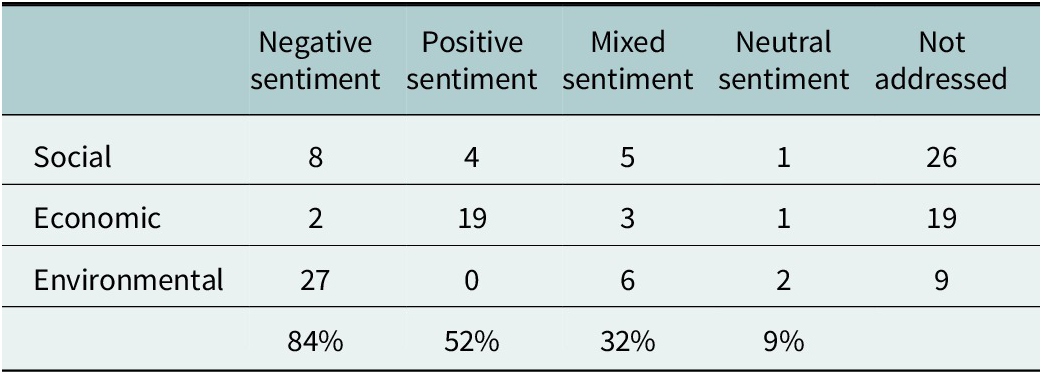

Sentiment analysis was manually performed on the 44 papers addressing impacts of tourism on coastal regions to determine the polarity of each paper (positive, negative, mixed or neutral) (refer to supplementary material). Each paper was reviewed and references to the impacts of tourism across the themes of: (1) society; (2) economy and (3) environment, were recorded as either positive, negative, neutral or mixed (i.e. in instances where both positive and negative impacts of tourism were reported for the theme). Manual sentiment analysis was adopted over automative programs to improve accuracy (Boukes et al., Reference Boukes, van de Velde, Araujo and Vliegenthart2020; van Atteveldt et al., Reference van Atteveldt, van der Velden and Boukes2021). In addition, to explore whether highly cited coastal tourism literature considered the impacts of tourism within the broader context of integrated coastal zone management (ICZM), the 44 articles were searched for terms relating to integrated management (i.e. ICZM, integrated and management). Finally, the analysis was compared with the findings of whole-of-sector reviews and reports, including grey literature, on the tourism sector (e.g. Honey and Krantz, Reference Honey and Krantz2007; Buckley, Reference Buckley2012) identified through Google Scholar to situate the findings within macro trends.

Results and discussion

Sentiment analysis focused on the impacts of tourism on social, economic or environmental conditions. As only three of the 44 papers referred to cultural impacts (Saveriades, Reference Saveriades2000; Almeida-García et al., Reference Almeida-García, Peláez-Fernández, Balbuena-Vazquez and Cortés-Macias2016; Cuadrado-Ciuraneta et al., Reference Cuadrado-Ciuraneta, Durà-Guimerà and Salvati2017; Grilli et al., Reference Grilli, Tyllianakis, Luisetti, Ferrini and Turner2021) and often combined social and cultural factors in their discussion, these papers were included in the ‘social’ category for analysis. Negative sentiment was present in 84% of papers, compared to 52% identifying a positive impact of tourism (Table 3). However, negative sentiment was strongest when relating to social and environmental conditions. More specifically, none of the 35 papers that discussed environmental conditions expressed solely positive sentiment, and only 17% showed mixed sentiment. Beyond the review, other papers have also explained that positive environmental impacts may be perceived rather than proven. For example, Diedrich (Reference Diedrich2007) states that some coral reefs may be perceived to be less impacted by a transition from extractive fishing towards tourism but that these assumptions may not be based on measured improvements. Of the papers that focused on environmental impacts, those impacts were often narrowly defined such as an impact on a specific species. For example, dolphins (e.g. Constantine et al., Reference Constantine, Brunton and Dennis2004; Lusseau, Reference Lusseau2004), penguins (e.g. Ellenberg et al., Reference Ellenberg, Setiawan, Cree, Houston and Seddon2007) and coral reefs (e.g. Zakai and Chadwick-Furman, Reference Zakai and Chadwick-Furman2002; Barker and Roberts, Reference Barker and Roberts2004). Moreover, the extensive range of environmental impacts is likely to have prevented their inclusion on the highly cited list (e.g. land cover change, wastewater discharge, land and marine litter, air pollution and water and energy consumption).

Table 3. Sentiment analysis of the 44 highly cited papers that focused on the impacts of tourism on coastal regions

The focus on specific impacts also partly explains the limited consideration of integrated management solutions, and that only two of the papers considered tourism within a broader context of ICZM. For example, while the results of the studies such as plastic pollution in coastal waters near tourist sites have management implications, the authors generally do not discuss integrated management. Instead, they seek to understand and recommend specific actions in relation to that specific impact such as variation in levels of marine plastic pollution based on tourism intensity and ways to address it in isolation. However, of the two papers that did consider ICZM, both included recognition of environmental impacts. None of the papers that focused on social or economic issues considered tourism within the context of ICZM.

In contrast to papers focused on environmental and social impacts, positive sentiment was evident in 76% of papers that discussed economic conditions. However, ‘economy’ was often vaguely defined with little detail on specific economic contributions, and where it was defined, it was largely discussed in terms of short-term inputs of capital, projections of employment opportunities for local residents or estimates of tourism expenditure. Notwithstanding that in specific cases, tourism can account for a substantial proportion of income for some communities, only a marginal proportion of the overall tourism revenue reaches those communities (Campbell, Reference Campbell1999; Sandbrook, Reference Sandbrook2010), which is particularly true in developing contexts (Lacher and Nepal, Reference Lacher and Nepal2010).

While several papers indicate significant perceived impacts (positive and negative) on social and/or economic conditions, the quantification of change in condition (e.g. income, employment, access to amenity and congestion) is scarce among the highly cited papers. Liburd et al. (Reference Liburd, Benckendorff, Carlsen, Uysal, Perdue and Sirgy2012) also point out that positive perceptions can differ to actual impacts and found that while tourism ‘has the potential to contribute to enhanced quality of life (QOL) through economic benefits … this can be at the expense of social equity, cultural identity and environmental sustainability’. Overall, there has been wide recognition of the need to ensure tourism is locally beneficial rather than impactful and has resulted in the development of a range of related concepts, from Community Benefit Tourism Initiatives (Simpson, Reference Simpson2008) to Pro Poor Tourism (Ashley and Haysom, Reference Ashley and Haysom2006). This recognition has been in part spawned by Murphy’s (Reference Murphy1985) seminal book, which proposed that tourism development should respond to local needs and led to numerous studies in this area in a range of contexts. For example, Ashley and Jones (Reference Ashley and Jones2001) discuss joint ventures between communities and tourist operators in Namibia. However, many of these studies tend to focus on business arrangements and profit sharing, rather than addressing broader long-term issues for affected communities. For example, Glup (Reference Glup2021), identifies some deeper impacts of tourism on communities such as the commodification of culture and displacement.

Honey and Krantz’s (Reference Honey and Krantz2007) report on ‘Global Trends in Coastal Tourism’ provide a more far-reaching perspective on the tourism sector, highlighting that economic impacts occur most significantly through land development. Furthermore, Honey and Krantz note that land development under the guise of tourism development is largely a short-term speculative investment that does not result in a sustained commitment to the community, environment or economy on the part of the developer. In addition, once the land development is complete and sold, the longer-term impacts of the development such as environmental degradation are usually unable to be compensated by the original developer. Honey and Krantz also found that this pattern is repeated throughout the world in both developing and developed world contexts, stating that ‘Corruption and cronyism, although difficult to document, is said to play an important role in coastal and cruise tourism decision-making, in both first and third world countries’ (p. 13). These findings are reinforced by Buckley (Reference Buckley2012), who found that political approaches are used to gain access to public spaces and natural resources. More recently, Clavé and Wilson (Reference Clavé and Wilson2017) note the ‘inherently “urbanising” nature of tourism development in the traditional coastal resort context’, whereby tourism development initially led to ‘path creation’, then to ‘path dependency’, but now has morphed into new models of urban development that differ from the ‘traditional coastal resort context’. However, Gormsen (Reference Gormsen1997) highlights historical cases of coastal tourism that also suggest coastal tourism being a form of property development. These trends exacerbate foreign ownership and wealth inequity within coastal regions and place increasing pressure on natural environments.

The polarised sentiment analysis, showing mostly negative sentiment for social and environment impacts, and mostly positive sentiment for economic impacts, also reflects the divergence within the tourism discipline. Higgins-Desbiolles (Reference Higgins-Desbiolles2020) highlights a division between tourism academics who focus on the benefits of tourism and support for the current sector business model, and those who recognise the negative impacts of tourism on environment, culture and sustainable livelihoods and call for reforms. This division has become pronounced during COVID-19 and amounts to a ‘war over tourism’, with one side arguing that critiques of the tourism sector cause harm to tourism operators, workers and tourists, while the other calling for the sector to be more ‘ethical, responsible and sustainable’ (Higgins-Desbiolles, Reference Higgins-Desbiolles2020).

While there have been calls for more comprehensive typologies of tourism for more than 25 years (e.g. Wall, Reference Wall1996), those that have been developed remain focused on micro-scale activities and interactions. For example, Acott et al. (Reference Acott, Trobe and Howard1998) discuss ecotourism as ‘deep’ or ‘shallow’ but not beyond the individual enterprise. And while Wall (Reference Wall1996) suggested that tourism needed to be viewed within a broader context of multiple other influences and impacts on communities, this ignored the more systemic influences and impacts that tourism has on broader social-ecological systems. However, there have been some attempts to raise these macro issues, albeit from a social justice, rather than a more-than-human lens. For example, Higgins-Desbiolles et al. (Reference Higgins-Desbiolles, Carnicelli, Krolikowski, Wijesinghe and Boluk2019) call for a rethink through ‘degrowing tourism’, where they argue for more emphasis on issues of equity, and where the rights of local communities should be placed ahead of those of tourists and tourism operators to make profits. More recently, Lamers and Student (Reference Lamers and Student2021) highlight that the social and environmental implications of globalisation should be considered within coastal regions, including mobilities and flows including global tourist flows.

As Gössling et al. (Reference Gössling, Scott and Hall2020) suggest, COVID-19 should present an opportunity to re-assess the growth trajectory of the tourism sector, particularly in relation to questioning whether more tourists actually result in greater benefits. However, like many other sectors, the opportunities for reform that presented through COVID-19 and the numerous other shocks before it such as the global financial crisis of 2007/2008, have not been translated into any significant global transformational action towards sustainability (Glavovic et al., Reference Glavovic, Smith and White2021).

Conclusions

This paper sought to explore highly cited papers focused on the impacts of tourism on coastal regions and to critique of the dominant view of tourism as a panacea to coastal futures. Sentiment analysis reflected the divide within the tourism discipline, where those papers that focused on the environment and society generally showed negative sentiment towards the impacts of tourism, while those that focused on the economy generally showed positive sentiment. However, most papers remain fixated on the local scale and impacts from specific tourism enterprises, which is reflected in the deficiency of highly cited papers that considered ICZM or other integrated management solutions. Currently, the highest cited papers on the impacts of tourism on coastal areas represent a disparate set of micro impacts, which cumulatively represent significant social-ecological challenges, but with limited interrogation of underpinning macro drivers. Hence the need for studies that focus on coastal tourism as a complex globalised system. In particular, there have been few highly cited studies that focus on the underlying business model of the tourism sector, which some sector reports suggest can more accurately be defined as property development. When viewed through this lens, the tourism sector may be seen as a far-reaching global business that exploits peoples and places for the benefit of wealthy elites. The findings have implications for both the scale of tourism research and also for considering tourism within the context of ICZM and sustainable development.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/cft.2022.5.

Supplementary materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/cft.2022.5.

Acknowledgements

This work contributes to Future Earth Coasts, a Global Research Project of Future Earth.

Author contributions

T.F.S.: Conceptualisation (lead); writing – original draft (lead); methodology (equal lead); formal analysis (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal); graphical abstract (supporting). C.E.E.-B.: Conceptualisation (supporting); writing – original draft (supporting); methodology (equal lead); formal analysis (equal lead); writing – review and editing (equal). D.C.T.: Conceptualisation (supporting); writing – original draft (supporting); methodology (equal lead); formal analysis (equal lead); writing – review and editing (equal); graphical abstract (lead). L.C.: Conceptualisation (supporting); writing – original draft (supporting); methodology (supporting); formal analysis (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal). M.L.T.: Conceptualisation (supporting); writing – original draft (supporting); methodology (supporting); formal analysis (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal).

Financial support

T.F.S., C.E.E.-B. and D.C.T. acknowledge the support of the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects Funding Scheme (FT180100652). The views expressed herein are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Australian Government, the Australian Research Council or Future Earth Coasts.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests exist.

Comments

No accompanying comment.