I. Introduction

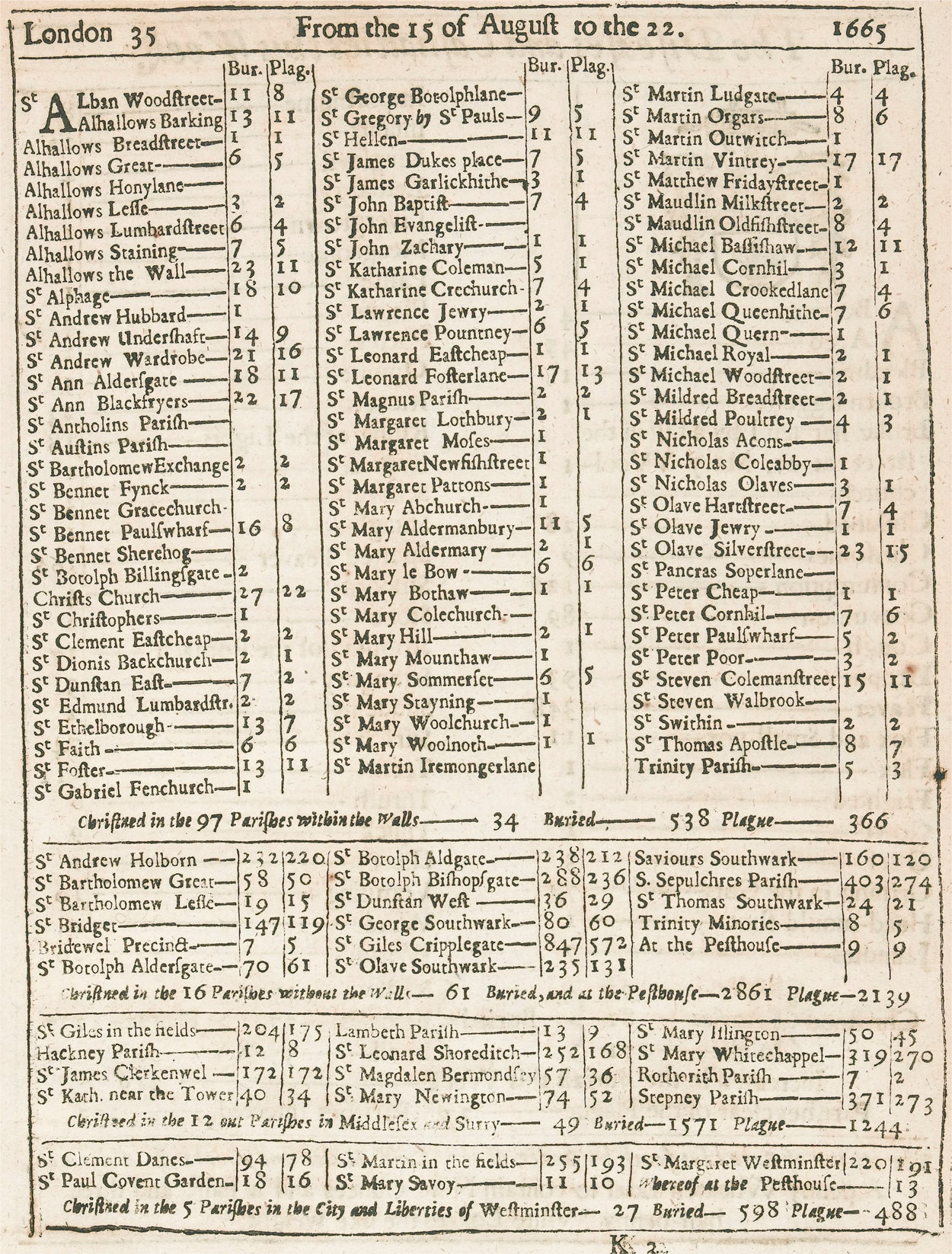

Plague is a long-standing problem for theology, going as far back as Genesis 12 and Thucydides's History of the Peloponnesian War (circa 404 BCE). Early modern England knew the plague of old, as did virtually every community in Europe, one of the most familiar and most feared of God's scourges. For many, outbreaks were moments of renewed religiosity, as the terrified sought comfort, the guilty sought redemption, and the pious sought understanding—and godly authors sought readers, producing a flood of spiritually inclined publications.Footnote 1 But as the seventeenth century began, major changes in how the plague was known, specifically in London, were afoot. Starting in 1603, the city authorities provided for the regular publication of bills of mortality, weekly records of births and deaths in the metropolis (fig. 1). In plague-time, each week's bill was scrutinized for clues as to the epidemic's whereabouts and movements, with the numbers circulating widely in a variety of forms, written and oral.Footnote 2

Fig. 1. Bill of Mortality for August 15–22, 1665. London's Dreadful Visitation; or, A Collection of All the Bills of Mortality for This Present Year Beginning the 20th of December, 1664, and Ending the 19th of December Following (London: E. Cotes, 1665), K3r. Image credit: Wellcome Images.

Early modern England was witnessing a profound expansion in numeracy across the social scale, as well as the development of new mathematical tools such as decimals and logarithms and the quantification of ever more aspects of the natural and human world.Footnote 3 These trends, coupled with the appearance of affordable mathematical textbooks, broadened the currency of numbers for articulating claims in seventeenth-century religious thought.Footnote 4 Theodore M. Porter characterizes quantification variously as “a political solution to a political problem,” a means of “projecting power and coordinating activity,” and “a social technology.”Footnote 5 It was all those things in early modern England, but the preoccupations of the age meant that such functions were always also theological.

Neither the seventeenth century nor plague introduced numbers into English religious thought. Numbers had had an immense significance in Christian spirituality since the apostolic age, and before that in both Jewish and Hellenistic traditions. Perhaps the greatest quantitative problem of the medieval period was working out the date of Easter.Footnote 6 Attempts to establish such spiritual statistics as the moment of Christ's birth or the depth of hell were already well established in the Middle Ages.Footnote 7 Simon Fish had marshalled quantitative arguments to convince Henry VIII to appropriate the wealth of the monasteries,Footnote 8 while pastoral manuals recommended elaborate number schemes to guide confessions (“sins against the seven commandments of the church, seven sacraments, Ten Commandments, seven deadly sins”).Footnote 9 The early modern drive to model scientific and moral knowledge after the abstract reasoning of mathematics proceeded in tandem with a demand for concrete, empirically derived data.Footnote 10

The regular publication of the bills of mortality from 1603 onward made numbers of this kind a thoroughly public commodity (and a peculiarly English phenomenon).Footnote 11 The centralization of early modern British printing, heightened literacy and numeracy rates in cities of the period, London's disproportionate size and sufferings in plague-time, and the ubiquity of the London bills in turn conspire to make this a largely metropolitan story.Footnote 12 That said, other English cities—including Colchester, Oxford, Bristol, Norwich, York, Chester, and Newcastle—experimented with the tabulation, if not the regular publication, of plague mortality.Footnote 13 Moreover, we will find London's numbers, and bills themselves, relayed to and by authors and readers across England and Scotland, and even into the Low Countries, disseminating arithmetical modes of thought far beyond the capital.Footnote 14

The corpus of sermons, homilies, tracts, poems, and pamphlets published during or just after the major epidemics of the seventeenth century (1603–1604, 1625–1626, 1636, and 1665–1666) is shot through with numbers supplied by the bills, used to rebuke sin, encourage reformation, and score polemical points.Footnote 15 The bills themselves became a fixture in the city's imaginary, while their contents were repeatedly and carefully cited to demonstrate God's rigor or mercy (as applicable). Because the bills’ figures were profuse, precise, empirical, and chronologically and geographically specific—tracking shifts in divine displeasure more closely and tying them to contemporary events more directly—they lent themselves to distinct forms of rhetorical, analytical, and theological work.Footnote 16 Rarely are numerical arguments the mainstays of these texts, but their ubiquity and diversity attest to the currency of numbers in early seventeenth-century English religiosity. More importantly, writers’ uses of the bills reveal a widespread quantitative savvy vis-à-vis novel sources of empirical data, affirming theology's place among the empirical disciplines that transformed the early modern world.

II. Bills of Morality [sic]

John Graunt, an autodidact draper who used the bills to develop quantitative demography, believed that they originated in response to the rampant mortality of plague-time.Footnote 17 The earliest, handwritten bills have been traced to various points in the sixteenth century, and while the circumstances of their creation remain unclear, their regular print publication began with the plague of 1603. Producing the bills became a major source of income for the Company of Parish Clerks, and they survived into the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 18 Ubiquitous registers of divine punishments, evocative of the kind of spiritual stocktaking clergy urged upon their flocks, the bills readily entered the religious literature of early modern London.Footnote 19 As Mark S. R. Jenner writes of the bills’ close cousins, the Lord Have Mercy broadsides, they “helped construct the imagery and imaginary of ‘popular Protestantism.’”Footnote 20 In the English case, at least, the bills’ data makes it impossible for the historian to separate the “body count” from “how the language of the disease could be used to talk about and connect up with wider social concerns and cultural preoccupations.”Footnote 21

Whatever their origins, the bills undoubtedly had a special connection to plague. The disease was the only cause of death tabulated parish by parish each week, and its epidemics cemented the bills’ place in England's consciousness. In turn, wherever the bills went, they “stimulate[d] discussion and analysis of plague.”Footnote 22 On August 3, 1665, Samuel Pepys rode from Deptford into Essex, and “all the way, people, Citizens, walking to and again to enquire how the plague is in the City this week by the Bill.”Footnote 23 Letter writers, from scholars like Joseph Mead to journalists like Henry Muddiman, gave correspondents regular updates on the weekly figures, often enclosing the bills themselves.Footnote 24 In a plague year, the publication of the bill every Thursday entered the weekly routine, just like church attendance on Sunday. In 1637, the balladeer Humphrey Crouch versified on The Belmans call on Thursday morning:

Crouch continued in an ominous vein:

The rhymester was not alone in spotting a parallel between the numbering of plague deaths and the tracking of sins. The two variables were not independent, sin being the accepted cause of plague, and the metaphor of sin as disease was truly ancient.Footnote 26 Many contrasted attention to the bills with the neglect of spiritual contagion, among them the nonconformist minister Matthew Mead: “So manie Thousands dead this Week, so manie another! . . . But were People formerly thus affected, whilst we were bringing this upon our selves? Did they cry out then, Oh how manie Thousand Oaths are sworn in a Week? . . . How manie Thousands Drunk, and how manie commit Lewdness? Had we had Weeklie Bills of such Sins brought in, they would far have exceeded the largest Sums that ever yet the Mortalitie made.”Footnote 27 Taking a different tack, the Jacobean preacher James Godskall decries what the land has assiduously counted in happier days: “thou hast gloryed in the number of the people, and hast long bene busie with a vaine Arithmeticke, in the numbring of thy riches, prosperitie, housen &c, and therefore the Lord hath punished thee, with a diminution of people; and hath teached thee another Arithmeticke.” God was countering the nation's “addition & multiplication” with “Substraction and diuision.”Footnote 28

The image of pestilence as God's bookkeeping pervades early modern plague writing, retailed by Thomas Dekker, Ben Jonson, Samuel Pepys, Daniel Defoe, and a host of lesser lights. The bills were the divine ledger, balancing sin with chastisement.Footnote 29 But, Godskall explains, they should also prompt a spiritual accounting of one's own, a reckoning of, and a reckoning with, one's sins.Footnote 30 Spiritual diaries often coopted the language and forms of accounting for the tracking of sins and virtues.Footnote 31 Pepys engaged in what Ernest B. Gilman calls “a system of sacred economics,” juxtaposing plague and salvation with his personal finances, all of them the trackable works of divine justice.Footnote 32 On the other hand, Robert Horne reduced all human arithmetic to insignificance next to divine infinitude. With God, “it is no more to saue his people when thousands die then when two; and when tenne thousands perish, then when ten (onely) are cut downe for the graue.”Footnote 33 One “I. D.” refused to condemn Londoners’ “diligence” towards the bills but lamented that this attention was not having the proper effect: increases in mortality did not inspire prayer or reformation, while decreases were met with overconfidence, rather than thankfulness.Footnote 34 Thomas Brewer cast the bill itself as a judgment on the people's response, for the “bill of Terror” would only worsen “if we still goe on in wickednesse.”Footnote 35 And the bills were not just a model for spiritual accounting, they helped to fill the ledger. Horne advises, “take your bill, or booke of tables, and write what God did fearefully in that great Plague, and strangely in remouing it.”Footnote 36 Horne's suggestion mirrored the widespread practice of updating a purchased broadside with fresh figures; printers frequently provided a blank space for this very purpose.Footnote 37 Contemporary diaries and family Bibles are likewise littered with mortality figures, a continuous record of the Lord's doings.Footnote 38

If the bills were a ledger of the wages of sin, it was generally agreed that the Lord was being lenient in his accounting.Footnote 39 The Cambridge minister John Edwards meditated on what he called “the plague of the heart,” whose bill of morality would outstrip that of mortality: “the Bodily Plague may kill it's thousands, but this [spiritual plague] it's ten thousands [1 Sam. 18:7].” (Note the biblical turn of phrase that identifies sinful Londoners with the Philistines slain by Saul and David.) If such a bill were drawn up, “not one Parish would be found clear, no not one house.”Footnote 40 A skillful preacher, Edwards is playing on his congregation's fears; the “searchers” who certified whether a house was infected or not (“found clear”), and the quarantine that marked out buildings as infected and sealed the inhabitants—diseased and healthy alike—inside for weeks on end were the stuff of London's nightmares.Footnote 41

The nonconformist Thomas Doolittle was more encouraging, urging readers to take comfort in the knowledge of their election. To find oneself in the bill of mortality would be no great matter, “when you are first in the Book of Life.” Such assurance comes “[w]hen you look upon your self as a dying man.”Footnote 42 Joseph Mead sent a friend “a Bill of the Plague the more to kindle your devotions on Wednesday [the day appointed for penitential fasts].” The bills, inventories of God's scourges, conduced to reflection upon mortality, the wages of sin, and divine justice.Footnote 43 But the bills were more than symbols: they were ink and paper publications containing substantial quantitative data about the plague. These numbers became, as Graunt puts it, “a Text to talk upon,” talk that was frequently theological in nature.Footnote 44

III. Fear and Mercy by Numbers

Before the numbers, however, there was the Word. The Bible, as Edwards's nod to Saul and David reminds us, is filled with numbers: the interminable lifespans of the patriarchs, the dimensions of the Ark and the Temple, and, most importantly for our purposes, death tolls. Thus, the sonorously round numbers of Scripture, the hundreds and the thousands, provided a ready vocabulary for reckoning plague mortality. Contributing to this pattern was the popular inclination toward round numbers and multiples of ten; even “political arithmetic”—Graunt's application of quantitative reasoning to problems of governance—turned upon ratios and proportions more than hard numbers.Footnote 45 As a result, much seventeenth-century numerical discourse involved what Margaret Pelling has termed “numberless number,” a culturally determined combination of the qualitative and the quantitative.Footnote 46

Yet when Richard Eedes, dean of Worcester, wrote that the 1603–1604 outbreak had “verefied that of the Prophet, a thousand shall fall beside thee, and ten thousand at thy right hand [Ps. 91:7],”Footnote 47 these numbers were neither plucked out of thin air nor solely a biblical quotation. Even the roundest figures had a claim to rest upon the bills of mortality, if for nothing more than a warrant—were any needed—that thousands were in fact dying. Late in 1666, Edward Reynolds, Bishop of Norwich, preached a fast-day sermon in which he intoned with the prophet Isaiah that God's hand was stretched out still (Isa. 9:17), “for he hath in these two years last past emptied this City and Nation in very many parts thereof, as we may I presume with good Reason compute, above an Hundred Thousand of her Inhabitants.”Footnote 48 By this point, London's bills had tallied more than seventy thousand plague deaths; given the Great Plague's ravages outside the capital and contemporary awareness that the bills underreported plague mortality, the bishop's computation is quite sound.Footnote 49

Despite the availability of annual summaries published as “the generall or the Kings Bill,” Reynolds's attention to gross totals was but one, and hardly the most common, way of reading the bills.Footnote 50 Graunt complains that his contemporaries “made little other use of them, then to look at the foot, how the Burials increased, or decreased.”Footnote 51 Such a modus legendi made good theological, as well as practical, sense: increases and decreases in mortality were God's modulations of his punishments. Londoners did not fail to discern the divine hand behind the bills: the poet Henry Petowe speaks of a decrease in mortality as “my blessed Sauiour lessen[ing] his weekly Number”; on October 22, 1665, the Essex vicar Ralph Josselin wrote in his diary that “God gave a great abatemt to the plague.”Footnote 52 Conversely, in 1604, the Suffolk rector Nicholas Bownd insisted on the continued necessity of fasting, for “Gods hand is not slaked, but rather stretched out still [Isa. 9:17],” seeing the disease “not to be ceased one whit, nay growing into greater extremitie and rage in manie places, from scores to hundreds, & from hundreds to thousands.”Footnote 53 In a country awash with providentialist thought, any movement (or no movement at all), regularity or irregularity, could be read as the divine will at work.Footnote 54 Josselin credits increases and decreases alike to the Almighty, altering only the tenor—“God good in or preservacon,” “Lord hold thy hand, proceed not in wrath,” “my soule records thy kindnes with meltings for thy mercy,” “Lord arise & helpe”—as appropriate.Footnote 55

Yet, Londoners did notice more than the direction of change; readers were no less attuned to the geographical specifics of the fluctuations: whether deaths were inside or outside the city walls, which parishes were clear, and whether trends were general or local.Footnote 56 Pepys, for example, remained sanguine as mortality rose in June 1665, since the deaths were mostly in the suburbs, while, in the autumn, his gratitude for the disease's retreat was tempered by the fact “that it encreases at our end of the town still.”Footnote 57 The basic function of the bills was to localize mortality by parish. James Balmford, rector of Saint Olave's, Southwark, congratulated his parishioners on their faithful attendance, “notwithstanding there haue died in our parish from the 7. of May [1603] to this day 2640.”Footnote 58 And because the bills were chronologically specific, citing them rooted a sermon or tract in time, at a particular point within the epidemic's arc. It was not uncommon to use weekly figures as temporal markers, as when Christopher Ness dated a tract, “Sept. 3 [1665]. When the slain of the Lord in one week, like 7 thousand Arguments, wrested this out of my hand.”Footnote 59

Precise figures slotted into familiar rhetorical patterns: exhortation, intimidation, and consolation. The parallel between the counting of deaths and the counting of sins could continue: “wee haue all mourned and sighed for the great number, that the pestilence hath encreased weekely, aboue three thousande,” observed Godskall, “but what maruaile, seeing there is none of vs, in whom haue not raigned aboue three thousand sinnes?”Footnote 60 With one question, the bill's dreadful arithmetic was mapped onto each reader's soul, multiplying the city's sins in a dizzying fractal. Even when quantified, the magnitude of God's punishments still failed to bring about the proper moral reckoning.Footnote 61 Scripture continued to furnish the lexicon for narrating mortality. Celebrating how “from 44.63. dead and buried of the mortality of Plague in one weeke, in that Citie, the Bill fell in few weekes to no lesse then halfe a score; yea to foure onely,” Horne effuses, “We were like them that dreame. . . . Surely, we cannot denie, that our mouth is filled with laughter, and our tongues with songs [Ps. 126:1–2].”Footnote 62 Joseph Mead, noting that the decline of the 1625 plague followed the seventh weekly fast, invoked the fall of the walls of Jericho after the seventh blast of the Israelites’ trumpets (Josh. 6).Footnote 63

Functional and rhetorical similarities should not obscure the multiple bases of authority in the use of precise numbers. In the passage from Robert Horne just quoted, it is the bills, not Scripture, that supply the fundamental “fact” of mortality decreasing by a certain amount. Indeed, in-line citations from the bills appear in Horne and others much like citations from the Bible—strings of numbers with italicized references (months replacing the names of books).Footnote 64 For that matter, the bills functioned as a second “text,” available, like the Bible, for individual perusal, whether personal copies, those reprinted by the authors, or those posted in public spaces (including many of the venues for major sermons). Though none of Horne's readers would deny that the Psalm spoke directly to their world, the bills were proximate in a more immediate sense. When Godskall bemoans the disparity in concern over “three thousande” dead and “aboue three thousand sinnes,” he makes no move that Matthew Mead would not make some sixty years later (“were People formerly thus affected, whilst we were bringing this upon our selves?”), but by deploying a more precise number from the bills, the Jacobean preacher adds the force of empirical authority to his harangue. Printing tables of mortality figures, as many authors did, performed a kind of transparency while guiding readers to contemplate the bills’ message in the proper spirit.Footnote 65 Simultaneously, Godskall and those like him imbued the bills with a spiritual aura when they cast a mortality figure in scriptural terms.

The bills permitted modes of intellectual work with plagues beyond declamation or description. Not confined to impressionistic renderings of an outbreak's dimensions, commentators could compare one week with another and contemporary epidemics with past visitations, be they biblical or historical.Footnote 66 They could combine data from different parts of the kingdom, and even from other kingdoms: in the same year, Crouch in London and Robert Jenison in Newcastle were both juxtaposing the two cities’ losses to compare the 1636–1637 outbreak with its predecessors.Footnote 67 Early modern “politic” thought taught its practitioners to look to history for comparanda, which might be keys to the motives and stratagems not only of kings but of the King of Kings.Footnote 68 Thus, some held that the ferocity of contemporary plagues exceeded that of their biblical predecessors (and from this drew predictable conclusions about contemporary morals). Riffing on the familiar verse from Psalm 91 (“A thousand may fall at your side, ten thousand at your right hand, but it [pestilence] will not come near you” [Ps. 91:7 NRSV]), William Crashaw laments, “wee haue not only seene a thousand fall at one side of vs, and ten thousand at another, but (alas, alas, that our sinnes should so prouoke our God) euen more then ten thousand on the one, and more then twenty thousand on the other.”Footnote 69 Conversely, the destructiveness of David's plague—seventy thousand struck down in three days (2 Sam. 24:15; 1 Chron. 21:14)—far surpassed even the worst seventeenth-century epidemics. In 1665, the Lincoln cleric John Featley took as his theme Psalm 119:52, “I remember thy Judgements of Old, O Lord, and receive comfort” when he reviewed the much greater devastation of biblical plagues: 14,700 in Numbers 16, 24,000 in Numbers 25,70,000 in 2 Samuel 24 and 1 Chronicles 21. “[Y]et we fear when One dyeth; we tremble when Ten; we run when Twenty; we are dismayed when an Hundred; we are hopeless, heartless, even almost quite dead already when a Thousand depart.”Footnote 70 Then again, the following year, surveying the full toll of the Great Plague, the York rector Josiah Hunter could cite the same passages and calculate that England's deaths “amount to more than the three fore-mentioned summs put together.”Footnote 71

The bills delineated the movement of the plague from week to week and over the course of a year, as well as geographically through the city's parishes. No biblical narrator or classical historian supplied anything like the same level of detail, keyed to time and place. Decrying the sins of the flesh, Bownd could note that “this pestilence hath been most hot, in that part of the citie that hath been most polluted this way, as in Shoreditch, and in the suburbs, and such out-places.”Footnote 72 In 1626, Horne, the preacher and polemicist Sampson Price, and royal chaplain Henry King all quoted liberally from recent bills, often juxtaposed with those for 1603, to illustrate the quasi-miraculous nature of the plague's sudden abatement.Footnote 73 (King added that the brevity of England's visitations—matters of weeks and months—paled in comparison with the decades-long pestilences of classical antiquity.)Footnote 74 Ten years later, Richard Sibbes, master of St Catharine's College, Cambridge, took the plague's swift decline, “that from above 5000. a weeke, it is come to three persons,” as proof that God alone was responsible.Footnote 75 The bills, moreover, provided the benchmarks for making such a judgment: on October 29, 1625, Joseph Mead declared, “God almightie be ever praised for his mercy,” because there had been a significant decrease in mortality “in a week that gave no reason to expect it.”Footnote 76 Brewer discerned further evidence of God's compassion in the bills’ actuarial patterns: the Lord seemed to spare the elderly (“he gives them time yet to repent”) and young men (“hee winkes at their faults a while, hoping they will bee wiser”). Instead, “looke over all your weekely Bils . . . and you shall finde, of Infants and young Children, twenty for one snatched out of their Cradles, because God will bee sure to increase his Saints in Heaven.”Footnote 77 Nicholas Bownd went so far as to extrapolate a causal explanation from the swift drop in the 1604 figures: that mortality “is fallen from three thousand and foure hundreth a weeke, to lesse than two hundred” should teach Londoners “what hee will doe for vs at all times when we pray.”Footnote 78

Empirical quantification was not the end to which all computation tended; on the contrary, exact data did much to fuel the rhetorical use of numbers. Indeed, the two modes, the precise and the rhetorical, are mutually constitutive. Even the lapidary numbers of Scripture make a claim to measure men, cubits, animals, and so on; conversely, even the plainest table of mortality figures makes a certain claim to authority and veracity. Seventeenth-century writers saw no intrinsic conflict between scriptural and empirical numbers; each form of authority strengthened the other.Footnote 79 Moreover, commentators were not above massaging data for rhetorical advantage. (Rounding was commonplace in the most utilitarian counts.)Footnote 80

The reader will have noticed that we have freely mingled voices from all four epidemics, that both quantitative modes—the rhetorical and the precise—recur from 1603 to 1666, and that the same writers move from one register to the other and back again. It would be difficult to exaggerate the magnitude of the changes in the kingdom from one epidemic to another; above and beyond the political environment, there were epochal transformations in religion (the rise and fall of Laudianism and Cromwellian Puritanism and the hydra-like proliferation of dissenters), natural philosophy (the feud between Galenism and chemical medicine and the emergence of corpuscular theory), and information (the appearance of newspapers). Not dissimilarly, there were vast differences between a sermon like Reynold's, preached to the nobility in Westminster Abbey, John Squire's, addressed to the crowd at Paul's Cross, and Henry Burton's, delivered to a Dissenting congregation in Saint Matthew Friday Street.Footnote 81 Each of these developments and distinctions was reflected in plague writing,Footnote 82 but the unmoved mover was the publication of the bills. Though the details of formatting might change and different parishes might be included, the availability of precise numbers, standardized for the entire city by a consistent scheme of organization,Footnote 83 remained a constant throughout the revolutions, political and intellectual, of the seventeenth century.Footnote 84

These numbers were reshaping Londoners’ understanding of their city and of epidemic disease.Footnote 85 Plagues were made the objects of detailed knowledge, knowledge that was geographically, chronologically, and historically specific and that outstripped the Bible in scope and sophistication. And if the bills were not of themselves quite as authoritative as Scripture, they had the advantage of being coeval with the events they described (much as early modern readers valued contemporary histories for their immediacy).Footnote 86 With such tools, enumeration fostered distinct approaches to the emergency at hand, opportunities that the arithmetically savvy population of the capital was not slow to seize.Footnote 87

Prominent among these possibilities was the ammunition the bills might supply against political and confessional opponents. In 1625, for example, some were struck by the fact that “the first abatement of the Plague was the week next Following that wherein came out the Proclamation against Papists.”Footnote 88 The politics of plague could be grimmer still: compare Brewer's kindly pestilential providence with that of his contemporary, Philip Vincent. Recounting the horrors of the Thirty Years’ War, Vincent lauded the plague God sent to Hanau in 1637, which killed more than 22,000 people. A Protestant city besieged by Catholic armies, “had not God sent that sicknesse to diminish their numbers, they had yeelded the towne through want of victuals.”Footnote 89 However anodyne the pastoral uses of plague numbers may have seemed thus far, the stakes rose precipitously as soon as one began to posit causes for God's punishments or mercies.

IV. Settling Confessional Accounts

Crouch ends his poem on The Belmans call with a warning:

But what caused the plague (what provoked God's wrath) and what caused it to abate (how said wrath might be appeased) were fraught questions. Consider Nicholas Bownd's use of the bills “to know what hee will doe for vs at all times when we pray,” or, in another treatise, his scriptural-arithmetical argument for penitential fasting. Judges 20 recounts that some forty thousand Israelites were slain in the first two days of the Battle of Gibeah, prompting an expiatory fast (Judg. 20:26). Since the 1603–1604 outbreak had carried off at least forty thousand souls, Bownd reasons, fasting was no less necessary.Footnote 91 These unexceptionable recommendations become inflammatory when the very words of prayers come into bitter contention and when fasting turns into a flashpoint of confessional conflict.Footnote 92

Myriad factions claimed “rhetorical ownership of plague,” constructing narratives of causation that aligned divine (dis)pleasure with their own beliefs. The imperative to rid the land of plague was a polemical advantage much to be coveted.Footnote 93 The bills of mortality were a text common to all, with the unsurprising result that the same numbers inspired contradictory interpretations. Ted McCormick rightly observes that enumeration “made Providence legible,” but the glossing of the text was eminently arguable.Footnote 94 William Sancroft, the dean of Saint Paul's, bemoaned “the many spiteful and unrighteous Glosses upon the sad Text of our present Calamity (on which every Faction amongst us hath a Revelation, hath an Interpretation;).”Footnote 95 Two moments illustrate the flexibility and universality of such combative narrations: the debate over fast days in 1636–1637 and the confessional anxieties of the Restoration, felt during the Great Plague by both Anglicans and Quakers.

We should briefly note a more rudimentary politicizing arithmetic with the timing of outbreaks, which might or might not make use of the bills. Some blamed the 1603 ecclesiastical census for the plague outbreak of that year—had not David's census been punished with a plague (2 Sam. 24; 1 Chron. 21)?Footnote 96 Preaching on Easter Monday of 1626, Henry King observed that the plague of 1603 followed the death of Elizabeth I, that of 1625–1626 the death of James I. “I thinke,” explains the chaplain, “the whole Land sensible of the losse of her DEBORAH, and our late most gratious SALOMON of euer blessed Memorie, . . . shedding Liues in stead of Teares.”Footnote 97 King's royalist gloss countered—without ever saying so—suggestions that these coincidences communicated divine displeasure with the ascending monarch.Footnote 98 In the wake of the Regicide, some radicals went further still: “From the first of King James, to the last of King Charls, England was seldom free from the Plague, but now (God be praised) the Land is free from that judgement, and our London Bils of Mortality have given in of the Plague none, for many weeks together.”Footnote 99

The first sustained religious controversy involving mortality figures began in late October 1636, when the Church of England issued new orders for penitential fast days. The orders restricted preaching to two one-hour sermons and forbade traveling to different parishes to hear more—to the fury of England's Puritans.Footnote 100 Preaching was the medium of godly edification and communal piety. Crucial at any time, the sermon was essential amid God's chastisements. How could Christians hope to appease the Lord if they neglected the Word of the Lord?

The response was almost immediate. First into print were Newes from Ipswich and The Unbishoping of Timothy and Titus, composed in November 1636 and published clandestinely. Both are likely the work of the splenetic Puritan polemicist William Prynne, at the time a prisoner in the Tower of London. Newes from Ipswich prophesied only failure for the newfangled fasts. “[W]e can never hope to abate any of Gods plagues, or draw down any of his blessings on us by such a fast, and Fastbooke as this, but augment his plagues and judgements more and more.” Indeed, Prynne asserted, that was exactly what had already happened. “[T]he totall number dying of the plague, the week before the fast being but 458. & 58. parishes infected, and the very first weeke of the fast 838 (treble the number the second last greatest plagues) and 67 parishes infected.” (For the weekly mortality figures for the last three months of 1636, see table 1.) Several cities formerly unscathed, among them Cambridge, Norwich, and Bath, had been “likewise visited since this fast begun.” This was “cleare evidence” of God's displeasure at “these purgations & the restraint of preaching.” When certain overly cautious Norwich churches had foregone fasting, preaching, and public prayer altogether, plague had visited them almost immediately. From all this Prynne concluded that England could not expect anything but further plagues so long as the oppression of the godly (and their sermonizing) continued.Footnote 101

Table 1. Plague mortality, October–December 1636.

Source: Londons Lord have mercy vpon us (London, 1637).

The Unbishoping of Timothy and Titus, Prynne's lengthy attack on episcopal authority, at one point invokes the plague that decimated Rome in the late sixth century, citing the twelfth-century churchman Peter of Blois's judgment that God was punishing the Italians’ profane pastimes on Sundays and feast days. Prynne confidently warned that the 1636 outbreak was a judgment on the “selfesame” sins, instantiated in the 1633 reissue of the Book of Sports (1617–1618). After all, both visitations began “on Easterweeke.”Footnote 102 Returning to the subject of preaching, Prynne pointed out that plague struck Christ Church Newgate Street, St Martin-in-the-Fields, and several other London parishes in the very same weeks that they had suppressed evangelical lectures. In those parishes already infected, the cessation of preaching and lecturing had been followed by increases in mortality. Meanwhile, St Antholin's, which had retained its lectures, remained free of the disease. As a rule, “were [sic] there is most sinne and wickednesse abounding, least knowledge and service of God, there is most danger of the plague,” and so it proved, with the disease “ever raging more in the disorderly suburbs of London, where they have usually least and worst preaching, more then in the City, where is better governement, life and preaching.”Footnote 103

These pamphlets exploit all of the ways in which the bills rendered plague knowable: its fluctuating death tolls, its extent and movement in time and space, and its history. The sheer quantity of numbers permitted an interested observer to find suggestive patterns that rooted a confessional agenda in the empirical warrant of plague mortality and the theological warrant of God's will. Assuming Prynne's authorship, the pamphlets’ detailed knowledge of the bills’ finer points may reflect the fact that the Tower was a key node in the distribution of the broadsheets.Footnote 104 It may also reflect a longstanding interest in numerical reckoning: in 1644, Prynne would be an active member of the Commission of Accounts established by the Long Parliament to review public finances.Footnote 105

Prynne was not the only Puritan calling attention to the plague-time errors of the Caroline Church. His collaborator Henry Burton published two sermons he had preached in November 1636, likewise attacking the fast orders. Burton savaged the “guelded Fast-book” that “I am sure brought us for a hansell [sc., a gift], a double increase of the Plague that weeke, to any weeke since the Plague began: and most terrible weather withall.”Footnote 106 Once again, the weekly bills were pressed into service, as Burton demanded, “the very first weeke of the Fast (whereas before the Sicknesse had a weekely decrease, and was likely, through Gods mercy, more and more to decline) what a sudden terrible increase was there, of no lesse than 377. which was double to any weekes increase, since this Sicknesse began?” God had made it clear “that he abhorres such a Fast, as of which his very judgements Speak, Call you this a Fast?” Conversely, Burton could cite the steep decline in the 1625–1626 plague to argue that “a greater plague than this was suddainly and miraculously remooved” by means of the old fast orders. The regime's logic threatened to turn the bills of mortality into an anti-Puritan weapon: “if but one Parish in London, or suburbs thereof, or but one house in that parish be infected, the pestilence thus continuing but in the least degree, and the Fast not ceasing, all Wednesday sermons in the whole City, must be suppressed.”Footnote 107

Prynne and Burton were each sentenced to a fine of £5,000, life imprisonment, and the loss of both ears for their intemperate attacks on the church hierarchy and the Stuart monarchy. But the Church of England did not let their criticisms, including of the fast days, go without a public response. The Laudian polemicist and historian Peter Heylyn, “commanded by authority” to refute Burton, flatly declined to meet the foe on his own ground on the subject of plague deaths, instead decrying Burton's arrogance in claiming to know the intentions of the Almighty.Footnote 108 Christopher Dow, Dean of Battle, also tars Burton as presumptuous in mounting an explanation at all, but first he critiques that explanation on its merits. The spike in mortality of October 27 no more proved God's displeasure with the fast orders than the (initial) victory of the Benjamites at Gibeah (Judg. 20:21–25) vindicated their cause or damned that of the other Israelites. Only then does Dow intone, “Gods judgements are unsearchable, and his ways past finding out [Rom. 11:33]; . . . it is impious presumption peremptorily to assigne any particular reason, either of their first infliction, or their progresse or continuance.” If a cause must be found, the Puritans’ own “murmurings & seditious railings against governors and government” seemed a more likely explanation.Footnote 109

In a May 1637 sermon at Paul's Cross—as prominent a venue as early modern London afforded—William Watts, the rector of St Alban's, Wood Street, contended still more directly with the Puritans’ plague arithmetic, evidently still a concern months after the plague had abated. “What if,” muses Watts, “the decrease of the Sicknesse (blessed be God for it) should be retorted on them, now that there are no Sermons”? It was no less plausible to say that the removal of preaching had occasioned the subsequent decline in mortality.Footnote 110 Whether Watts knew it or not, just such a counter-construal of the bills and the fasts had been attempted earlier in the year by John Squire, the well-connected vicar of St Leonard's, Shoreditch. Preaching at St Paul's on New Year's Day, Squire took as his text Psalm 50:15, “Call vpon me, in the time of trouble; I will heare thee, and thou shalt Praise me.” The vicar insisted that Londoners had called upon God through the fasts, and God had heard them—circumscribed preaching notwithstanding.Footnote 111 His first task was to exonerate the fast orders from responsibility for the increase of October 27. To do so, he seized upon the bills’ production schedule: since the first fast was on Wednesday, October 26, while the data for the bills was gathered in on Tuesday mornings, “we may conceive, that in those times of mortalitie, upon Tuesday and Wednesday, halfe the number for the weeke following were dead, or, as dead marked for whom we could expect no Fruit from our Fasting.” By choosing a different baseline for his arithmetic—the bill published on 3 November, “the first full weeke, that followed our first day of Fasting”—Squire could tell a different story about what the bills portended. The resulting effort to “compute GODS goodnesse’ is worth quoting at some length:

The first weeke, Wee did call upon GOD, in the time of the Plague, by Prayer and Fasting; and God did heare us in that time of our trouble. So the Burials decreased 190.

The second weeke, Wee did call upon God in the time of the Plague, by Prayer and Fasting: and God did heare us in that time of our trouble? So the Burials decreased, 139.

And so it continued all the way through to “The seventh weeke”: “Wee did call upon GOD in the time of the Plague, by Prayer and Fasting. God did heare us in the time of our Trouble, and the Burials Decreased likewise, 61.”Footnote 112 If the litany is tedious to read, it would have made for powerful listening, each iteration hammering home the link between prayer, God's mercy, and mortality. Early modern observers perceived the statistical distortions produced by the bills’ production process,Footnote 113 quirks that might be exploited to challenge an opponent's interpretation. (Squire concurred with Dow in blaming the plague's increase on “the Seditious Rayling” of the Puritans.)Footnote 114

Leaping forward to 1665, the confessional terrain shifted, but similar strategies of interpretation and argument endured, as did the possibility of contradictory interpretations of a single set of numbers. When plague struck in 1665, “in such a juncture of time, when it could not have been more prejudicial to the affairs of the Nation,” the usual sense of divine punishment was heightened by the nation's many traumas since the last great outbreak.Footnote 115 A brutal civil war, complete with regicide, had been followed by political instability. The Restoration had come about due more to the power vacuum after Oliver Cromwell's death and the machinations of George Monck than any upsurge of affection for the Stuarts, resulting in a fragile, febrile political settlement. After eleven years of Puritan rule, radical Protestantism remained a force to be reckoned with, to say nothing of the welter of nonconformist sects. Fears of rebellion had been realized as recently as 1663. The plague coincided with a reversal in England's fortunes in the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–1667); as the epidemic was finally subsiding, London was devastated by fire. The leaders of England's established church could have been forgiven doubts about just how firmly established it was.Footnote 116

Like Squire some thirty years before, Anglican writers faced an immediate challenge: to account for the plague while avoiding the imputation of blame to the Crown or the Church of England.Footnote 117 John Bell, clerk to the Company of Parish Clerks, marshalled theology, history, and arithmetic to tackle the problem in his London's Remembrancer—a compendium of weekly mortality figures for eighteen different years between 1604 and 1665. Bell appended to this multiplicity of numbers six “Observations,” the last on the cause of the plague. The clerk quotes from a plague sermon of 1603 by the Jacobean bishop Lancelot Andrewes, to the familiar effect that plagues are “caused by Gods wrath against Sin.”Footnote 118 Following the sequence of Andrewes's exposition, Bell turns to the Bible to identify the sins at issue, taking four examples: Numbers 16 (punishing “the peoples Rebellion” against Moses and Aaron), Numbers 25 (punishing “Fornication”), 2 Samuel 24 and 1 Chronicles 21 (punishing David's pride), and Isaiah 37:2, Kings 19, and 2 Chronicles 32 (punishing Sennacherib's blasphemy). “The two first of these were caused by the people, the other two by Kings,” a difference Bell sees reflected in distinct patterns of mortality. Both passages from Numbers state “the number of the people, without particularising what they were that died, whether Men, Women, or Children, or all of them.” By contrast, the biblical text seems to specify that men were struck down by the plagues of David (2 Sam. 24:15; 1 Chron. 21:14) and Sennacherib (2 Chron. 32:21).Footnote 119 From this Bell concludes “that all the Plagues wherewith it hath pleased God to visit this Nation” can be attributed to the sins of the people, not those of their rulers. As he explains, “I cannot find . . . a Plague within this Nation which spared either Sex or Age.”Footnote 120 Though this last proposition is meant rhetorically, from 1629 onward, the weekly bills offered Bell proof, supplying separate christening and burial figures for men and women.Footnote 121

Having cleared Charles II of responsibility with this elegant piece of special pleading, Bell suggested that, as in the days of Moses and Aaron, the Great Plague was a punishment for “the sin of Rebellion”—that is, the Civil War and especially the Regicide. Bell anticipated the objection that the gap of time was improbably long (and, by extension, that a more proximate cause should be sought). “When God will make inquisition for blood [Ps. 9:12], there is none can tell; but when he doth, then he will not fail to remember them that shed it. This When, hath not at any time since the death of our late Martyred Soveraign, come so near as now.”Footnote 122 It is no accident that Bell harps on obedience. The need to keep order in the capital was real: political turmoil in London had helped precipitate the Civil War. Particularly once King Charles II decamped to the provinces in July 1665, guiding popular interpretations of the plague was of paramount importance, lest dissenting groups seize the opportunity to make trouble.Footnote 123

The dissenters were keeping busy during the Great Plague, but less with fomenting rebellion than with preaching, writing, and praying. Like the Anglicans, British Quakers had already had ample cause for disquiet before the plague appeared. A series of statutes—the Quaker Act (14 Cha. II c. 1), the Act of Uniformity (14 Cha. II c. 4), the Conventicle Act (16 Cha. II c. 4), and the Nonconformists Act (17 Cha. II c. 2)—codified the persecution of religious dissenters. Up and down the country, Quaker meetings were disrupted and Friends harassed, arrested, imprisoned, or banished. As they worked to overturn these policies,Footnote 124 the bills offered a means of proving, as the itinerant Quaker preacher Thomas Salthouse had it, that “Persecution is the crying sin for which the Land mourns.”Footnote 125 Addressing an audience that was by definition unfriendly, Quaker authors sought to forge an empirical connection between pestilence and the regime's religious policies. The Friends’ reliance on the bills is an early modern exemplar of Porter's claim that quantitative arguments tend to be the weapons of the weak, “a response to conditions of distrust attending the absence of a secure and autonomous community.”Footnote 126 It also resonates with the Friends’ privileging of lived experience over academic scriptural exegesis.Footnote 127

It was not by chance, insisted Salthouse, that the plague had first arisen in London, “the great City where Persecution and Banishment for worshipping God did begin.”Footnote 128 More specifically, Quakers made much of the fact that one of the first plague fatalities in the city proper (as opposed to the suburban parishes) occurred on Bearbinder Lane. This was in May 1665, less than two months after the first sentences of banishment were handed down against London Friends—one of whom, Edward Brush, had lived on Bearbinder Lane.Footnote 129 A couplet by the Quaker poet John Raunce pointed out that the plague first appeared “[n]ear to that place, from whence that good man went, / Whom first ye forc'd away in Banishment.”Footnote 130 Richard Crane recounted the persecution of the three men and then explained how God swiftly “visited this City with a rebuke, and that they might take notice of it, within a few doors of that faithful Man's house E. B. a house was shut up . . . of the Plague, and indeed it was the first that I ever heard of in the City.”Footnote 131 The connection between Quaker protomartyr and plague mortality required that the localized knowledge of the bills be matched by localized knowledge among the Friends. Still a small and tight-knit group, Quakers knew where their co-religionists lived; they maintained their own registers of births, marriages, and burials, in conscious repudiation of Anglican parish record keeping (which tended to keep Friends out of the bills of mortality).Footnote 132 Some Quaker pamphlets included lists of the martyrs, a kind of counter-bill of mortality that individualized, rather than aggregated, victims.Footnote 133

The swift execution of Brush's sentence added to the significance of the timing: the first convoy of deportees had sailed for Jamaica shortly before the plague struck.Footnote 134 Then, Crane asserts, “Weekly-bills began to declare the Judgements of a just God.” Just as the initial, small-scale deportations had been followed by steadily larger groups, “even so hath the Judgments of God traced that malicious spirit, first in small numbers and so with greater, as any that will make the observation upon the weekly-bills of Mortality may find it so.”Footnote 135 Crane describes Friends driven into exile “in the face of the City, in whose streets the bills of Mortality were the day before handed that signified the cuting off by death 3014. and so as they have encreased the numbers for Banishment, the Lord hath increased his Plagues.”Footnote 136 When the following week brought further persecutions, Crane took a grim satisfaction in noting that “1016. is increased in the Judgement in this Bill, for no less then 4030. is cut off,” a neat rejoinder to claims that eradicating the Quakers would end the plague.Footnote 137 Quaker authors all agreed that the Anglicans had failed to understand the bills’ providential message, and so to resolve the crisis. By citing exact figures and inviting readers to verify their reckoning—“any that will make the observation upon the weekly-bills of mortality may find out”—the Friends at once coopted the bills (an Anglican record of Anglican lives and deaths) and prompted the individual discernment their faith encouraged.Footnote 138

Another Quaker, Thomas Greene, also informed London, “as thou hast multiplyed thy cruelty, so the Lord hath caused his Plague to encrease,” but claimed to have discovered a more exact proportion between the two. The exile of fifty-five Quakers—“near threescore”—on August 4 was met by an increase in mortality to “near three thousand by the weekly bill” (2,817 plague fatalities reported for the week of August 8).Footnote 139 One suspects that no matter what the numbers were, Greene would have contrived to fit them together. But that is in some sense the point. The terror of plague, fraught confessional politics, and the significance given to every occurrence by providentialism lent weight to even the most tenuous coincidences. This is not to say that Greene was being disingenuous, merely that the bills’ abundance of numbers keyed to contemporary realities made it easier to find empirical confirmation of the divine message. Establishing the connection was all the more crucial in light of the relatively small numbers of victimized Quakers; where Anglican writers looked to events of national significance, the Friends were claiming that the persecution of a still minor sect had unleashed the greatest epidemic since the Black Death. The disproportion between dozens of Quaker martyrs and tens of thousands of plague victims attests at once to the Friends’ sense of the cosmic injustice done to them and the difficulty of the case they were making.

Plague has always been ripe for rhetorical manipulation, and its seventeenth-century politicization is hardly a discovery. What has not been appreciated is that the bills gave the polemicists of 1636 or 1665 a weapon unavailable to the Marian ideologues who blamed the epidemics of their day on Edward VI's Protestantism or their Elizabethan successors who attributed the 1563 outbreak to London's “residual catholicism.”Footnote 140

V. Conclusion

Plague years inspired many (though by no means all) early modern Britons with renewed religious fervor.Footnote 141 They also both fed on and fueled the diffusion of numeracy, quantitative reasoning, and access to precise data across British society. The confluence of these two patterns brings the interpenetration of number and theology into high relief. Almost immediately, the bills of mortality became a fixture of London culture, deployed by preachers, poets, playwrights, moralizers, and satirists alike. As indices of the plague's movement across time, space, and the bodies and parishes of the city, the bills quantified God's will, permitting that will to be interpreted and contested in numerical terms, often for confessional advantage.

This essay has considered bishops and deans, infamous pamphleteers and iconic diarists, but the most prominent beneficiary of the bills was unquestionably John Graunt, who used them to develop political arithmetic. Graunt pored over mortality figures going back six decades, with special attention to plague years, to uncover “for the first time the significance of the massed life events of women and children as well as men,” including pioneering attempts at calculating an infant mortality rate and constructing life tables.Footnote 142 His 1662 book, Natural and Political Observations, won him admittance to the Royal Society, a modicum of contemporary fame, and lasting renown as the founder of actuarial mathematics.Footnote 143

Less hallowed and—probably not coincidentally—no longer extant is Graunt's “something about religion.”Footnote 144 That the first political arithmetician should write a “something about religion” was a sign of things to come. Religious questions were always to be part of political arithmetic's remit—indeed, the slogan coined by Graunt's collaborator William Petty, “number, weight, and measure,” was lifted from Wisdom 11:20.Footnote 145 Like most early modern scholars, the arithmeticians prided themselves on how their work revealed God's glory. By the eighteenth century, their ranks were dominated by clergymen.Footnote 146 One such, William Derham, viewed the bills of mortality as “evidence of God's transcendental design structuring human life.”Footnote 147 And it is too infrequently recalled that that numerical evidence was organized (both geographically and bureaucratically) through the parish system, compiled by church officers whose responsibilities also included the maintenance of parish registers and other ecclesiastical records. Since at least the early Tudor period, ecclesiastical infrastructure had doubled as a means of organizing data collection, with the parish serving as a basic unit in a range of quantitative enterprises—registers of births, christenings, and burials; accounts of tithes, rents, and expenditures; poor relief; censuses of paupers, vagrants, and attendees (and absentees) at services. As a result, the parish became a crucial site for developing and teaching methods of record keeping and enumeration and remained so through the eighteenth century.Footnote 148

It would be too much to claim that Graunt and Petty took their cues from the likes of Nicholas Bownd and William Prynne. But David R. Bellhouse, Stephen J. Greenberg, and James C. Robertson have shown that the political arithmeticians possessed no monopoly on sophisticated readings of the bills of mortality. Londoners were cognizant of the extraordinary resource they received each week.Footnote 149 More than that, they knew how much was required to maintain it. When, in 1665, the printer E. Cotes published a compilation of the weekly bills for the previous year, he explained that he had struggled to find mortality figures for the 1625 outbreak; his book sought to ensure “[t]hat Posterity may not any more be at such a loss.”Footnote 150 Men like Bownd and Prynne, in prompting Britons to think about population, disease, time, and geography in numerical terms, and to scan numbers carefully, with an eye to the causal stories they could tell, formed the intellectual milieu for the emergence of political arithmetic and for the immense authority invested in quantification over the eighteenth century.Footnote 151 In plague-time, London “became a laboratory in which power and knowledge were not simply exercised but rethought, applied and re-evaluated.”Footnote 152

The religious writers we have encountered merit a place alongside the familiar heroes of “applied mathematics” in the humanities avant la lettre, like Jean Bodin, Giovanni Botero, and Justus Lipsius, whose efforts were more secular in purport and/or more erudite in audience.Footnote 153 Precisely because the Godskalls and the Crashaws framed their arithmetic in religious, popular terms, they reached a much broader public.Footnote 154 No less than the city fathers of Gregorio Dati's Florence who guided their military policy by calculation of Milan's resources, these clergymen “reasoned pen in hand, and said, as of a sure thing, ‘It can only last so long.’”Footnote 155 What links them is not a common methodology, still less a common project, but their exploitation of a common resource—the bills of mortality—for religious purposes. It is this resource that distinguishes “ecclesiastical arithmetic” as something new in the history of empirical theology.

We can see these patterns ramifying in other branches of religious thought, such as the venerable traditions of biblical chronologies and investigations of scriptural demography (whether the earth might be peopled within the revealed timeframe, whether it had room for the bodily resurrection of everyone who ever lived). These inquiries continued apace in the seventeenth century, but began to make use of the demographic data gathered in the bills of mortality and of the methods of political arithmetic.Footnote 156 Hard numbers contributed much to physicotheology, “the attempt to demonstrate God's providence through the empirical study of nature,” as well as to other strands of natural theology and biblical exegesis.Footnote 157 The language of mathematics likewise bolstered efforts to logic God into existence: Peter Gunning, a prominent Anglican bishop contemporary with many of our authors, was said to have “proved by Geometrie that there was a Deitie,”Footnote 158 while his Roman Catholic coeval Pierre-Daniel Huet dreamed of “proving religion through a methodical sequence of propositions similar to those one finds in geometry.”Footnote 159 Mordechai Levy-Eichel has recovered the history of “moral arithmetic,” “the attempt to formalize and mathematize moral thought” through a mathematical style of analysis.Footnote 160

True, the trend was neither universal nor irresistible: deeply symbolic, culturally determined attitudes to number persisted (as they do to this day).Footnote 161 Nevertheless, the currency of quantitative reasoning was growing. With each epidemic, the quantity of printed material about plague increased, and the bills were unparalleled in the speed and freedom with which they circulated. By 1665, the weekly numbers were being published in newspapers and newsletters.Footnote 162 Graunt's Observations was a bestseller, seeing multiple printings, imitations, and pirated editions.Footnote 163

The fate of numeracy is of a piece with the social diffusion of other habits of observation and interpretation, among them the “politic” style of political analysis and new modes of reading, listening, and traveling. In England and across Europe, fresh energy was applied to the challenge of gathering, ordering, and disseminating immense troves of data, old and new.Footnote 164 “[M]uch that was previously unknown could now be known and known more widely.”Footnote 165 The ecclesiastical arithmeticians had no notion of setting their shoulders to the wheel of an epistemic shift; their concerns were avowedly spiritual and political. They sought to move the beleaguered believers of the kingdom, to bring about moral renewal, redoubled devotion, pious obedience, or changes of policy. But in so doing they made use of an unprecedented and unparalleled numerical resource, vindicating both the influence of new instruments in transforming early modern knowledge-making and religion's place in the story of “scientific” observation.Footnote 166