Introduction

Since their development in the UK in the early 1970s psychiatric intensive care units (PICUs) have become an integral part of general psychiatric services (Crowhurst & Bowers, Reference Crowhurst and Bowers2002). It is widely accepted that PICUs were designed to create a safe and controlled environment for the management of acutely disturbed psychiatric patients on a short-term basis, with high staffing levels and a limited number of beds (Dolan & Lawson, Reference Dolan and Lawson2001). In recent years psychiatric intensive care has begun to distinguish itself as a sub-speciality of general psychiatry (Beer et al., Reference Beer, Pereira, Paton, Beer, Pereira and Paton2001), research in the field is extensive, and national guidance on standards for PICUs in general psychiatry has been issued (Department of Health, 2002).

The development of medium secure psychiatric care has occurred contemporaneously but there is almost no literature regarding the provision of intensive care within medium security. It has been suggested that PICUs are a rarity in forensic psychiatry (Dolan & Lawson, Reference Dolan and Lawson2001) but there is no published authoritative data.

The deficits in knowledge and diversity of service provision previously apparent in general psychiatry were highlighted by Beer et al. (Reference Beer, Paton and Pereira1997) and developed further by Pereira et al. (Reference Pereira, Beer and Paton1999). We wondered whether the same deficits are now apparent in forensic psychiatry.

AIMS

To conduct a survey investigating the provision of psychiatric intensive care within NHS medium secure units in England and Wales, gaining preliminary information about PICU size and clinical structure, and using this information to inform a discussion regarding PICU provision in medium security.

Method

A variety of sources were used to identify the MSUs in England and Wales, including personal knowledge and a list kindly provided by a Department of Health colleague.

The same anonymous questionnaire was sent to the service director and the lead clinician for the intensive care. The questionnaire provided spaces for free text responses. Respondents were asked about the size of the MSU, whether there was a dedicated PICU within it, or whether there were plans to develop one. They were then asked for further information about the service structure of the PICU, or their alternative strategies for caring for their most difficult to manage patients.

The first round of questionnaires was sent out in 2004. To update this data set questionnaires were sent out in 2005 to those MSUs who initially indicated that they were in the development phase of providing intensive care facilities.

Data was analysed using SPSS (version 10).

Results

A total of 30 MSUs were identified. Responses from the service director, the lead clinician, or both, were received from 26 out of the 30 MSUs surveyed, giving a response rate of 87%.

Table 1 shows the range of PICU provision with information about the size of, and number of consultants in, the MSUs.

Table 1. Range of PICU provision, MSU size and number of consultants

Among the seven MSUs with a PICU the average number of PICU beds was 6.25. The clinical service structures were as follows:

1 had recently changed to a single registered medical officer (RMO) and multidisciplinary team model.

1 was intending to switch to a single RMO model and already had dedicated input from other disciplines in place.

1 had a lead multidisciplinary team to develop policy but the patients were managed by all clinical teams.

2 had no lead clinician but did have dedicated input from disciplines other than psychiatry.

2 had no lead clinician and no dedicated input from other disciplines.

Of the six MSUs developing a PICU only two stated that they had decided upon a future service structure. One commented that all clinical teams were to have admission rights and the other reported that two of their consultants would have admitting rights with one consultant accepting lead responsibility for the running of the unit.

14 of the 19 MSUs with no PICU indicated that difficult to manage patients were cared for within specific areas of the acute wards.

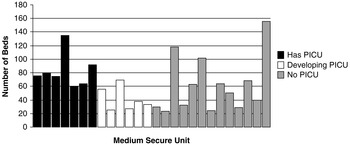

Figure 1 shows the size of individual MSUs grouped by PICU provision. There was a significant difference in size between the three groups (χ22 = 6.442, p = 0.040). Further investigation showed that this was accounted for by a significant difference in size between MSUs with a PICU and those developing a PICU (Mann-Whitney U, Z = −2.714, p = 0.007). There was no significant difference between those with and those without a PICU (Z = −1.744, p = 0.081), between those developing a PICU and those without one (Z = −0.702, p = 0.483), or between those without a PICU and the other two groups combined (Z = −0.718, p = 0.473).

Figure 1. Number of beds within each medium secure unit

There was no significant difference in the number of consultants between the groups (χ22 = 2.381, p = 0.304).

DISCUSSION

The response rate was extremely good for a postal survey. It is important to recognise that we were unable to access an authoritative list of NHS Medium Secure Units. This seemed to us a major obstacle but we are confident that we identified the majority of units open at the time of the study. We may have attempted to contact some units that had closed down. It is interesting to note that Beer et al. (Reference Beer, Paton and Pereira1997) encountered the same difficulty in their survey of general psychiatry.

The main limitation of this pilot survey is obviously the lack of depth of information regarding service structure and the reasons for the current development of PICUs at some MSUs. In part this is a consequence of the postal survey method and the balancing of response rate against length of questionnaire. This information has proved invaluable however in forming the basis for the following discussion.

Why might PICUs have been developed in medium security?

Fifty percent of the MSUs surveyed either have a PICU or are developing one. Therefore, they are clearly not a rarity. Although this survey only provides a cross-sectional snapshot there appears to be a growing trend for the provision of intensive care within medium security. Presumably PICU development within medium security is related to a perceived clinical need. To our knowledge this need has not been demonstrated by prior research. We are aware of one MSU that has closed down a PICU due to lack of need (Dolan & Lawson, 2001).

It is generally accepted that patients within medium security pose a higher level of risk for acting violently than those within lower secure environments. This is particularly true for the acute, perhaps newly admitted, patient. The resultant level of need in terms of security is higher for this population than those in primarily rehabilitative environments within the same hospital. As Gordon (2001) stated, the PICU thus allows the more stable group within the hospital to undertake their treatment and rehabilitation without undue excessive restrictions.

It is often argued that the reduction in the availability of high secure psychiatric beds over the last ten years has led to an increased level of disturbance among those patients admitted to medium security. There is little evidence to either support or refute this hypothesis. However, it may be that growing pressure to accept patients from maximum security at an earlier stage of their rehabilitation has led to greater risk within medium security, in turn driving a need for an additional level of care within medium security.

Perhaps the clinical role of MSUs has changed. This could be part of a gradual super-specialisation of forensic psychiatry fuelled by similar changes in general psychiatry. The improvement in the provision of mental health care in prisons may have led to an increased recognition and need for the compulsory treatment of higher risk patients within medium security.

It is probable that MSU staff characteristics have changed over time. The increased awareness and utilisation of PICUs in general psychiatry may have increased the pressure on MSUs to provide a similar service. It is conceivable that a reduced tolerance for violent behaviour in the acute ward milieu has lead to the concentration of patients in a specific area, to be cared for by specialist staff trained in the requisite skills.

More generally, one could hypothesise that there has been a societal shift in line with political rhetoric, which has lead to both a greater awareness and a decreased tolerance of risk. Together with ever-greater economic pressures on mental health services, this tends to promote physical security at the expense of procedural and relational security. PICUs may therefore arise more frequently in an effort to manage this perceived risk.

Why have PICUs not been developed in medium security?

Fifty percent of the MSUs surveyed still have no designated PICU and are thus presumably of the belief that they are managing satisfactorily without one. Nearly seventy-five percent of the MSUs with no PICU indicated that difficult to manage patients were cared for within specific areas of the acute wards. We are unfortunately unaware of the details of these provisions. Such facilities are often referred to as extra care areas, and have been defined by Dix (Reference Dix1995) as closely supervised living spaces, away from the main clinical area. To our knowledge no study has compared clinical outcomes between PICUs and extra care areas in medium security.

Further explanations may include the transfer of high-risk or difficult to manage patients to maximum security or the private sector. It is also plausible that MSUs without PICUs contain smaller, lower stimulus, acute wards with higher staff to patient ratios, thus negating the need for additional intensive care.

The development of larger MSUs in recent years may bring greater numbers of more disturbed patients within a single hospital, creating an apparent need for a dedicated intensive care unit. We found no evidence of a difference in size between those MSUs with an established or developing PICU and those without.

Are national standards needed for medium secure care?

The guidelines for the provision of PICUs in general psychiatry make a number of recommendations about the physical nature of the units and the most appropriate service structure (Department of Health, 2002). In particular a lead clinician and a dedicated multidisciplinary team are considered necessary. We have demonstrated great variation in service structure at present. The majority of MSUs that were in the process of developing a PICU at the time of the study had not considered the clinical service structure. If we accept that PICUs are a beneficial therapeutic addition to medium security, forensic psychiatry needs to consider whether the national minimum standards are appropriate. It is interesting to note that intensive care provision was not discussed in the recent Department of Health Guidelines for medium secure services (Department of Health, 2007).

There are obviously a number of potential advantages to a dedicated PICU multidisciplinary team and lead clinician being utilised within medium security: an available evidence base to utilise from general psychiatry; staff often feel more supported; and skills can be shared across disciplines.

Countering this however, forensic psychiatry places great emphasis on continuity of care as a medium through which risk is understood and managed. It may be that this need for continuity of care outweighs the advantages of dedicated multidisciplinary input. It is debatable as to whether one team following patients through from PICU to rehabilitation increases patient throughput and prevents excessive periods in intensive care. Given the increased length of admissions within medium security and the possibility of multiple periods in PICU, patient preference in terms of continuity of their treating team must also be considered.

Our experience suggests that there may be divergent views both between and within disciplines regarding dedicated PICU clinical teams. Many clinicians value the diversity of work and greater continuity of care that following their patients through all levels of care provides. On the other hand, nursing and ward-based staff tend to report a preference for working with a single multidisciplinary team.

As Zigmond (Reference Zigmond1995) stressed, patients on intensive care wards are usually the sickest in the service. Given the array of discussion points raised in this paper, further research is clearly required to understand the reasons for the changing practice that we have identified, to develop a base of knowledge to inform service structure and to investigate the effects of different structures on clinical outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are very grateful to Dr Sayeed Haque for his help and advice regarding statistical matters.