1 Introduction

Studies that explore the link between the representation of judges, photography and mass media tend to focus on the appearance of cameras in courtrooms and the reproduction of the resulting photographs in the press.Footnote 1 But, as Keller (Reference Keller, Crowley and Heyer1991/2011) notes, there is a considerable gap – more than fifty years – separating the birth of photography in the late 1830s and the technological developments that led to the mass production and circulation of photographic images via newspapers at the end of the nineteenth century. What, if anything, was happening during the intervening period? The argument presented here is that photography as a form of mass media was having an impact upon the production and consumption of representations of the English judiciary from the early 1860s. This was brought about by the invention of a form of photographic picture known as ‘carte de visite’. One goal of this paper is to consider the impact this particular type of photography had on what appears within the frame of these portraits of judges. The second goal is to explore the way they were consumed and displayed. As various scholars have noted, the meaning of pictures is not solely derived from what lies within the frame. Their meaning is also shaped by practices of curation and the mode and location of their display (Pointon, Reference Pointon1993). Known as ‘album cards’, carte portraits were produced with a particular display in mind: individual portraits were integrated into a larger collection of cartes in an album. Album-making and album-gazing were central to the experience of carte portraiture (Perry, Reference Perry2012, p. 741). Few albums survive. After introducing the carte album and the practices of consumption and curation associated with this mode of display, three albums containing carte portraits of senior members of the English judiciary will be considered. The objective is to examine the place they occupy in these three displays and to consider the meanings generated through their use.

The project draws upon carte portraits in a number of archives. The library of one of the Inns of Court in London, Lincoln's Inn, has a collection of over 400 carte portraits. Many of the sitters are judges.Footnote 2 All the cartes in this collection are linked to albums, the majority of which are intact. Two will be considered below.Footnote 3 Another source is London's National Portrait Gallery (NPG). It has an extensive collection of carte portraits. A search of the NPG catalogue for portraits of senior English judges in post between 1860 and the 1880s generates numerous carte portraits. In many cases, they are the only photographic portraits of the judicial sitters in the gallery's collection. In several cases, there are multiple carte portraits of the same sitter in slightly different poses, all from the same studio, produced at the same time.Footnote 4 The NPG collection also includes an album that contains a number of carte portraits of judges. It is catalogued as ‘The Tichborne Claimant Trial Album: cartes-de-visite by various photographers, 1860s–1870s’ (Unknown, undated).Footnote 5 The research also draws on my own collection of carte portraits purchased via eBay.

Before embarking upon the study of these photographic portraits, a brief introduction, using existing research, provides some background about their production and consumption. A number of issues will be highlighted. The first is the factors that come together in the carte format, thereby turning photography into a mass-media phenomenon. The second is their impact on the production of portraiture. The focus then shifts to examine their distribution and consumption. As most readers are likely to be unfamiliar with carte de visite pictures, I start with some basics.

2 Carte de visite: the basics

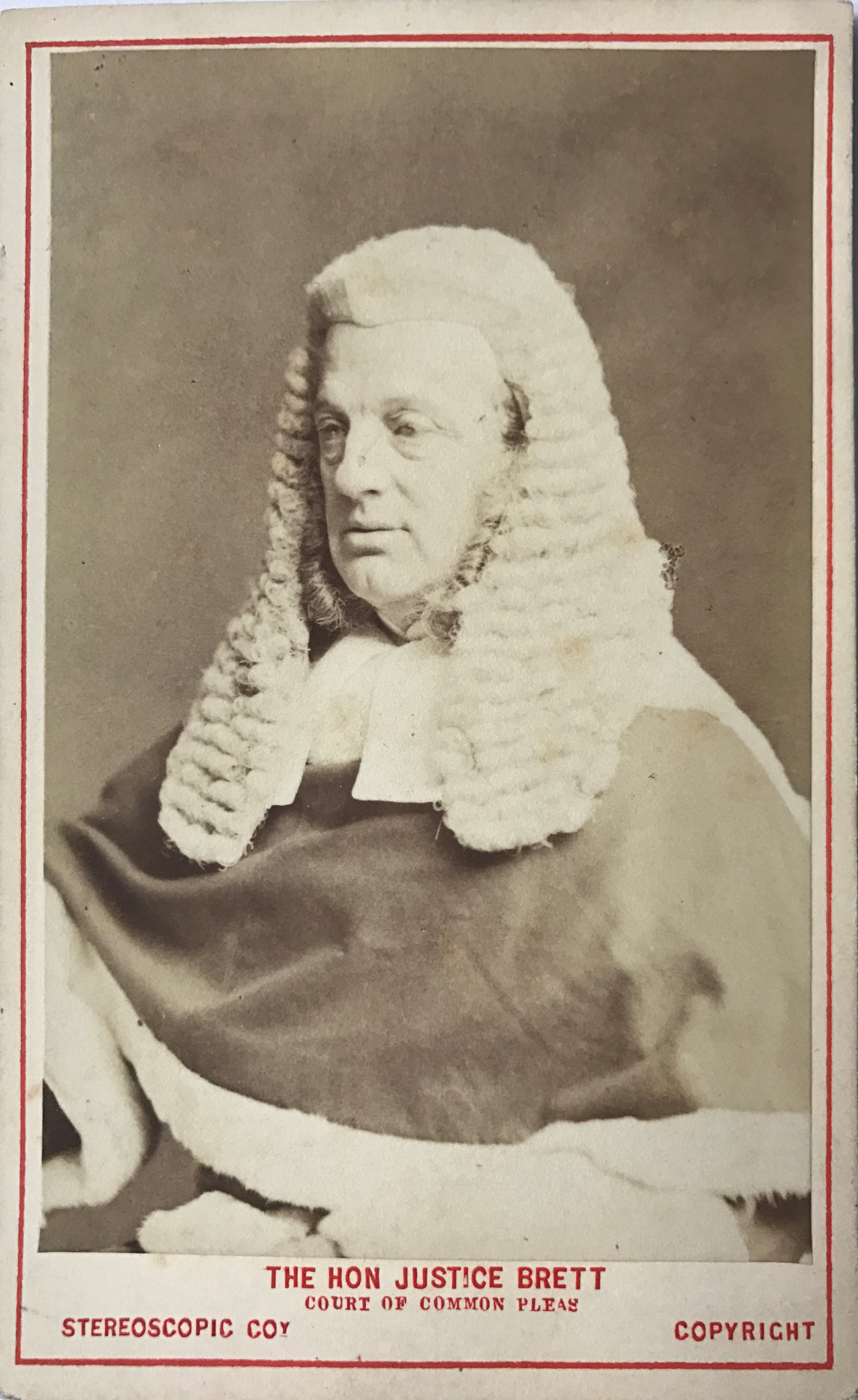

The portrait of ‘The Hon Justice Brett Court of Common Pleas’ (Figure 1)Footnote 6 is an example of a carte de visite portrait of a judge. The name ‘carte de visite’ is in part a reference to the size of the picture. Measuring approximately 89 by 58 millimetres (3.5 by 2.25 inches), carte photographs are about the size of a visiting card. The photographic paper print is mounted on card. The barely visible difference between the surface levels of the print and the mount reveals the thinness of the print. In this case, a red graphic line printed onto the card fames the print. This example also includes a caption: the sitter is named by reference to his institutional position. Viewing them today, their small size, everyday materials and less-than-perfect production qualities suggest an object that is at best a cheap historical curiosity rather than a technological marvel and an innovation that was a cultural sensation.

Figure 1 The Honorable Mr Justice Brett, Court of Common Pleas. He was appointed to the post of judge in the Court of Common Pleas in 1868. With the reform of the higher courts in 1875, he became a judge of the Common Pleas Division of the High Court. In 1883, he was appointed to the post of Master of the Rolls. The caption on the carte suggests this photograph dates from before the 1875 reforms. Copyright: L.J. Moran.

In common with many carte portraits, the name of the studio that produced the picture is printed below the photograph. In this case, ‘Stereoscopic Coy’ is an abbreviated reference to the ‘London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company’. It had studios in two of London's primary retail locations: Cheapside in the City and Regent's Street in the West End (Moran, Reference Moran2017). The company's brand is on the reverse side. In this case, it is made up of a variety of symbols: of royal patronage, high culture (medallions incorporating Greco-Roman iconography) and technological innovation (‘Sole Photographers to the International Exhibition 1862’). Woven together by delicate tracery, the branding connects social, cultural and technological values to the studio name and this particular type of portrait.

Carte portraits do not include a date.Footnote 7 But, with reference to the Court of Common Pleas in the caption, the court did not survive the 1875 reforms of the High Court of England and Wales and the branding on the carte that was in use between 1873 and 1878Footnote 8 suggests it dates from sometime between 1873 and 1875.

3 Innovations that changed photography

‘Carte de visite’ is a type of photographic picture made possible by the combination of two developments: one in chemistry, the other in the technology of camera optics. The albumen print process was a development in the chemistry of photography that enabled the production of the first cheap and relatively easy-to-use, commercially viable method of producing a photographic print from a negative plate onto paper (Stulik and Kaplan, Reference Stulik and Kaplan2013). In 1854, a multiple-lens camera was patented by an enterprising French photographer, Andre Adolphe Eugene Disdéri (McCauley, Reference McCauley1985). Different lenses could be opened to the light at different times to capture the sitter in a variety of poses on a single negative in a single sitting. Together, these developments enabled the production of a portrait at a fraction of the cost of any other method of portraiture (McCauley, Reference McCauley1985, p. 27). The repeated use of the negative allowed the speedy production of multiple copies of the same quality. In their combination, these factors worked to produce a form of photography capable of being mass produced.

The carte photograph was introduced into England in 1857. In the decade that followed, there was a frenzy of production and consumption. Nineteenth-century commentators invented new terms to describe it: ‘carteomania’ and ‘cardomania’ (Teukolsky, Reference Teukolsky2015). One estimate is that between 300 and 400 million cartes were sold in England between 1862 and 1866 (Darrah, Reference Darrah1981, p. 4). In part, this was driven by people using relatively small amounts of their disposable income to commission carte portraits of themselves and other family members – the primary market. But it was also driven by studio-led initiatives to produce cartes of sitters for sale to the public – the secondary market. These mass-produced portraits of noteworthy individuals for sale to the public were not only displayed in street-level showcases and window displays of the studios (Hargreaves, Reference Hargreaves, Hamilton and Hargreaves2001, p. 43; Moran, Reference Moran2017), but could also be bought in other outlets such as fine-art shops, stationery supply stores and booksellers. Prices varied from a shilling to one and sixpence, depending on the fame of the sitter.

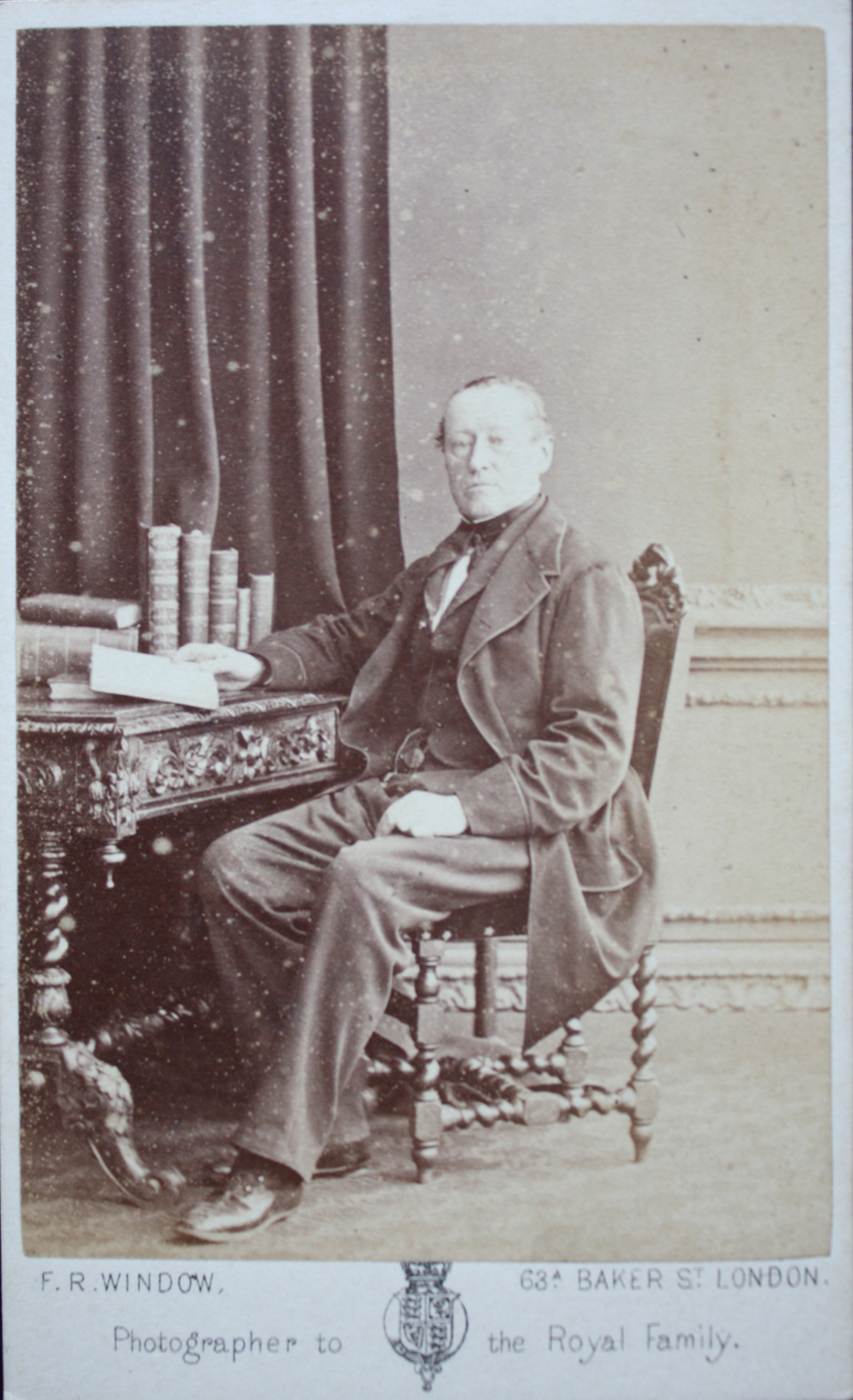

The carte portrait of Sir Alexander James Edmund Cockburn (Figure 2), who held the office of Chief Justice from 1859 to 1880, has no caption. He is dressed in civilian clothing, rather than robes of office. Is this a portrait commissioned by him for personal use or one that was also made for sale to the public as a result of the studio's own initiative for sale to the public? With regard to carte portraits of sitters who were well-known public figures such as Cockburn, it is now difficult, if not impossible, to differentiate between those produced for the primary and secondary markets (Perry, Reference Perry2012, p. 738). In the early days of production, the two markets were closely connected. Studios were proactive in offering this new form of portraiture to eminent and celebrated individuals. The resulting portraits were offered to the sitter for their personal use and, at the same time, the studio gained a right to produce copies for sale to the public. Plunkett's (Reference Plunkett2003a) study of the English copyright records during the first ten years of production discovered that, in one year alone (1866), forty-four carte portraits of Queen Victoria, seventy-seven of the Prince of Wales (the heir to the throne) and seventy of Princess Alexandra of Denmark (the Prince's young wife) were produced for sale by studios. Hargreaves (Reference Hargreaves, Hamilton and Hargreaves2001, p. 45) estimates that, between 1860 and 1862, up to 4 million cartes of Queen Victoria were sold to the public. While many carte portraits of the queen include a caption referencing her title, not all of them do. Inviting and encouraging eminent and celebrated people to use this new product was a marketing strategy – a way of raising the profile of a new product to grow a market for it.

Figure 2 Carte de visite portrait of Sir Alexander James Edmund Cockburn by F.R. Window Studio, 63A Baker Street, circa 1873. The sitter held the office of Chief Justice from 1859 to 1880. Copyright: L.J. Moran.

There is evidence that carte portraits of judges were made for sale to the public. A catalogue entitled ‘Carte de Visite Portraits of the Royal Family Eminent and Celebrated Persons’ dated 12 January 1866Footnote 9 lists the cartes available for purchase from S.B. Beal, a ‘Photographic and Fine Art Dealer’ based in the City of London (Beal, Reference Beal1866). The length and diversity of the list of sitters in the catalogue offer some evidence of what Hacking (Reference Hacking2010, p. 871) describes as the zealous pursuit by studios of established members of the elite and other contemporary eminent and famous people for purposes of their commercial exploitation. Common to all is public visibility linked to public recognition, reputation or significance – what van Krieken (Reference van Krieken2012) describes as people with attention capital. This is linked to the sitter's ‘well-knownness’, or ‘renown’ (Kornmeier, Reference Kornmeier2008, p. 278). The appearance of senior judicial office-holders, Lord Chancellors, Chief Justices and Justices of the High Courts, in this catalogue is testament to their public visibility, which was being commodified and resold in the market for carte portraits. The appearance of multiple carte portraits of judges who were in post in the 1860s and 1870s in the NPG collection suggests that many studios were involved in producing carte portraits of senior judges. As members of an eminent group in society, it is perhaps no surprise that the portraits of at least some them appeared in the long lists of cartes for sale to the public. With all these points in mind, I now want to turn to consider what appears within the frame of these portraits.

4 Carte portraits of judges: what appears within the frame?

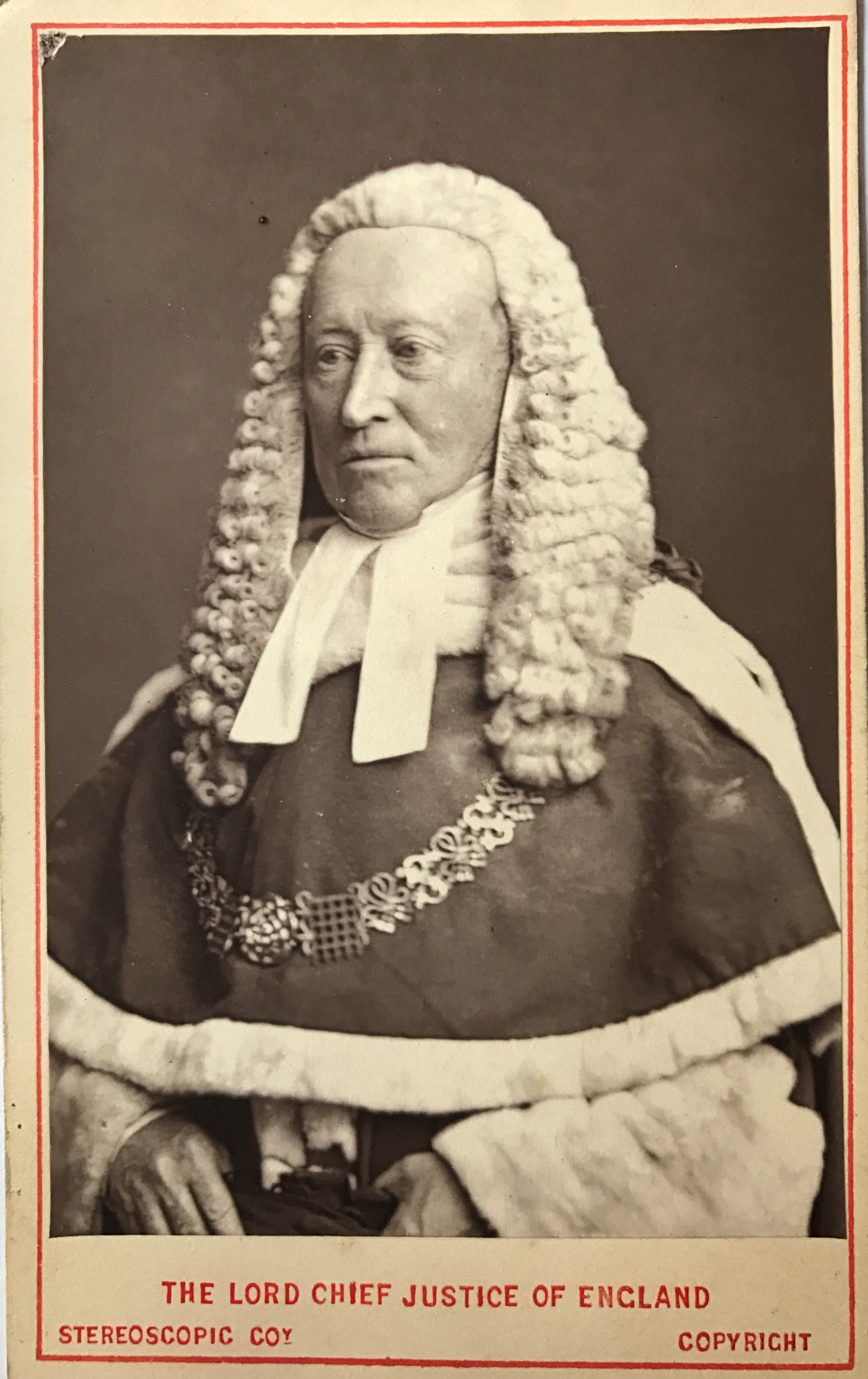

The cartes in Figures 1, 3 and 4 all come from one of the most prolific studios: the London Stereoscopic and Photograph Company.Footnote 10 Like those that appear in the Beal catalogue, all are judges in the highest courts. Justice Brett (Figure 1) was a judge in the Court of Common Pleas. Figure 3, ‘The Lord Chief Justice’, is a portrait of Sir Alexander James Edmund Cockburn that dates from between 1873 and 1875.Footnote 11 ‘Rt Hon Lord Selbourne’ (Figure 4) was Lord Chancellor, at the time the head of the judiciary, for two periods: 1872–74 and 1880–85.Footnote 12

Figure 3 ‘Lord Chief Justice of England’ produced by the London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company of London, circa 1873–78. Copyright: L.J. Moran.

Figure 4 Rt. Hon. Lord Selborne. The studio logo on the back of the CdV is in a style used by the studio between 1880 and 1885. He held that office for a second time from 1880 to 1885. He is shown here in judicial robes worn by a Lord Chancellor. Copyright: L.J. Moran.

While there is some variation in composition, all three have much in common. Backdrops are plain, props and furnishings are largely absent. The focus is the body of the sitter. However, much of the detail of the sitter's body is missing. All have a compositional preoccupation with the display of ceremonial regalia. The body functions more as a surface for the display of the symbols of the office of judge: the wig, robes and ornaments. If the upper-body compositions of the carte portraits of Selborne (Figure 4) and, to a lesser extent, Brett (Figure 1) give greater prominence to the judicial face, the full-bottom wig frames the face, obscuring much of the detail of the head. The carte portraits of judges in Lincoln's Inn and the NPG collection suggest that, far from being a composition unique to the London Stereoscopic Company, it was pervasive.

Art historians have identified these compositional characteristics as those associated with a particular style of portraiture: state portraiture. Jenkins defines state portraits as representations of rulers or their deputies (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins1947).Footnote 13 Judges, as the Sovereign's organ of justice, are easily accommodated within the parameters of the phrase ‘rulers or their deputies’. State portraits have a specific purpose: foregrounding the qualities and characteristics of the office rather than the personality and the character of the individual office-holder. The individual is represented as their very embodiment (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins1947, p. 1). As such, it is a form of portraiture that resorts to special methods of handling the sitter, using distinctive aesthetic codes designed to give visual form to a particular set of institutional attributes, characteristics, qualities, particularly concerned with social and political rank. Full and three-quarter body poses dominate. The face takes up a relatively small area of the portrait's surface. Backgrounds are monotone or loosely figured, offering little to distract the viewer's eye from the symbols of office displayed on the sitter's body. All the carte examples shown here suggest that the long aesthetic tradition of state portraits used in making painted portraits of judges was incorporated into the portraits of judges made through the new medium of carte photography.Footnote 14

The portrait of Cockburn (Figure 2) in which he appears in civilian clothing also dates from the early 1870s.Footnote 15 There are no traces of ceremonial judicial regalia. His pose is less formal, sitting adjacent to a small domestic writing desk on which he rests his right arm. His pose and gaze, looking directly at the camera, suggest a momentary break from studying a text that lies open on the desk. Overall, the composition suggests a private setting and an intimate moment. As in the other portrait of him, there is little in the background to distract the eye from the sitter; the heavy, dark curtain offers a simple contrast. As noted above, it is now difficult to identify whether this carte was produced for the primary market alone. The appearance of a caption with his institutional title in some examples of Cockburn's civilian portraits suggests that they may have been produced for the secondary market.Footnote 16 How are we to make sense of this different carte portrait of a judge?

Plunkett's (Reference Plunkett2003b) work on the media image of Queen Victoria and her family suggests that the informality in carte portraits should not necessarily be read as antithetical to the portrayal of an institutional authority figure. He notes that a key feature of Queen Victoria's multimedia engagement in general and her use of carte portraits in particular is that they contain no trace of the usual royal regalia. Costumes and props are those of everyday bourgeoisie domestic respectability and poses are informal (Perry, Reference Perry2012, p. 729). While the adoption of this style of self-fashioning and self-presentation by social and political elites in their portraits predates both the invention of the carte format and the reign of Victoria,Footnote 17 its adoption by the royal family and its dissemination via carte portraits increased its visibility and popularity. So, while the portrait of Cockburn in Figure 2 is visibly very different from the long tradition of state portraiture that appears within the frame of his portrait in Figure 3, the former is also legible as a portrait of an institutional figure of authority. What has changed is the adoption of the signs of bourgeois respectability to show the values and virtues of the office that the he personifies.

The appearance of many cartes of judges dressed in civilian clothing in the carte collections of Lincoln's Inn and the NPG suggests that Lord Cockburn was not alone in his adoption of these symbols for the purpose of institutional self-fashioning and self-presentation. If the adoption of this more informal style of the ‘ordinary bourgeois subject’ had the potential for long-established institutional elites to disappear from view, because they look like any other bourgeois subject, it was also evidence of their reformation as the legitimate authority within a rapidly changing society.

To stop here in the analysis of what lies within the frame would be premature. One thing that all these carte portraits of judges have in common is that they exhibit what contemporary commentators described as the failings of this type of portraiture (Perry, Reference Perry2012, p. 730). One of the ‘failures’ is linked to the capacity of the technological innovations to capture the physicality of the sitter in sometimes unflattering and idiosyncratic detail. For example, the robes of both Justice Brett and the Lord Chief Justice Cockburn look rather creased and unkempt. In Figure 3, Cockburn's stiff collar appears to cut into his face. The inner lining of his wig sticks out beneath the curls. Despite the ability of the wig to hide the detail of Cockburn's head, the camera captures the detail of the fleshy undulating surface of his face: his fleshy jowls and the wrinkles under his eyes, on the bridge of his nose and between his eyebrows. Lord Selbourne's overbite and receding chin and Brett's full lower lip are other examples of facial idiosyncrasies captured in detail. The appearance of these unflattering and idiosyncratic details goes against the tendency of state portraiture to idealise and perfect the sitter. It is contrary to an aesthetics that emphasises the transcendent aspects of the sitter's institutional personae.Footnote 18

But the numerous carte portraits of Queen Victoria and other senior members of the royal family and the buoyancy of sales of these portraits does not suggest that their ‘failings’ led to the conclusion that they were a form of portraiture to be avoided by elite figures or shunned by consumers. Plunkett explains that royal interest was closely linked with the ability of the camera's lens to represent the idiosyncrasies of the sitter, and thereby its capacity to humanise the subject (Reference Plunkett2003b, p. 68). These failings were engaged as part of an initiative to modernise the representation of established institutional authority. The signs of the authority figure's humanity were an antidote to the symbols and aesthetic traditions linked to forms of aristocratic authority. They were signs associated with the growing power of the urban bourgeoisie. Plunkett's study of Queen Victoria suggests that it is important not to forget that the undulating surface of the face with all its idiosyncrasies functions as part of the symbolic assemblage that is within the frame. The veracity of the representation produces symbols that link the authenticity of the representation to the institutional virtues the sitter embodies, such as proximity, openness and transparency.

The informality of costume and composition of the Figure 2 carte portrait of Cockburn put on display a break with the conventions of portraying an established authority figure. But cartes that apparently reproduce the aesthetic conventions of state portraiture in the photographic portraits of judges also incorporate signs of change. In these portraits, it takes the form of the symbols of the sitter's ordinary fleshy humanity. Both informal and formal photographic portraits have the effect of making authority figures look more ordinary, more commonplace, more like the viewer (Perry, Reference Perry2012).

Before leaving what lies within the frame, I want to highlight one final factor that impacts on the way the frame shapes the meaning of the picture: the size of the portrait. The small size of carte portraits was also characterised as one of their failings. This is particularly so with portraits of elites in general and state portraits in particular: they tend to be large in scale. A judicial example is the portrait of Sir Matthew Hale Chief Justice of the Kings Bench from 1671 to 1676. This full-body portrait is over six feet high.Footnote 19 In contrast, carte portraits are small: they can be held in the hand. Large-scale full-body portraits have long been associated with the expression of high status and social distance. Small portraits are associated social proximity and intimacy (Lloyd, Reference Lloyd, Lloyd and Sloan2009, p. 18).

Holding the carte portrait of a senior judge in the palm of the hand provides the viewer with an experience of physical and social proximity: an intimacy with an otherwise remote subject. This is amplified by the fidelity of the picture.Footnote 20 These experiences were more difficult, if not impossible, to achieve by other techniques of reproduction available at the time. This, Plunkett suggests, was part of the magic and the allure that attracted both viewers and sitters to carte portraits (Plunkett, Reference Plunkett2003a, p. 45). The ‘insinuating and sensuous realism’ (Plunkett, Reference Plunkett2003b, p. 145) is central to the viewer's experience of mediated quasi intimacy (Thompson, Reference Thompson1995) with the sitter. From our current position, it is difficult to imagine the magic and the shock of the viewer's experience and the novelty of the perception of the transparency, openness and the truth of the judicial authority figures that were portrayed in this manner for the first time. The ability to hold these small portraits close to the body also draws attention to a commonplace of portrait scholarship that the location of the picture and the mode of display impact on its meaning (Pointon, Reference Pointon1993). I now want to turn to consider in more detail how carte portraits were displayed and how the mode of display shaped the meanings of the portraits of judicial sitters.

5 Judges in the album: locating the meaning

Carte portraits were rarely viewed in isolation. When on display for sale to the public, they were always presented in the shop window in multiple portrait displays (Moran, Reference Moran2017). People who purchased them also displayed them with other carte portraits. Cartes were displayed in an album. Di Bello (Reference Di2007) describes the album as a blank container. Carte albums have a common format. Each double-sided laminated-card page has a number of frame mounts cut into it; the standard is four per side.Footnote 21 Each vacant mount on the album page is an irresistible invitation to fill the space (Hargreaves, Reference Hargreaves, Hamilton and Hargreaves2001, p. 47). Album-making and album-gazing were central to the experience of this form of portraiture (Perry, Reference Perry2012, p. 741).

Filling the blank spaces involved a number of activities. Some relate to the acquisition of cartes. These include shopping for new cartes (commissioning photographs or buying readymade cartes). Others include obtaining new cartes through other social encounters. For example, it became fashionable to use them as calling cards – a phenomenon particularly associated with city settings (Batchen, Reference Batchen, Long, Noble and Welch2009, p. 88). A portrait assisted in authenticating identity in the relatively anonymous context of a city (McCauley, Reference McCauley1985, p. 30). Giving and exchanging cartes also became linked to specific celebrations, such as New Year's Day (McCauley, Reference McCauley1985, p. 28). Negotiating swaps with other album owners was another mode of acquisition.

Other activities relate to curation: generating a system or a narrative that makes and makes sense of the display as a whole and the position of each carte within the album. Di Bello (Reference Di2007) notes that the work of curation was often undertaken by women. On occasions, it not only involved the arrangement of the portraits, but sometimes it also involved decoration of the album's pages (Di Bello, Reference Di2007, pp. 24–25). An example of this in an album that includes carte portraits of judges in the collection of the State Library of South Australia. It is attributed to Mary Giles and is entitled ‘Prominent South Australians’. Page 3 of the album is made up of a display of seventeen portraits; all are legal professionals, several are judges. Like the other pages in the album, this page has also been decorated. At the centre is the first Chief Justice of South Australia, Sir Charles Cooper.Footnote 22 Foliage has been drawn around the edge of the card mount. Strands of foliage also tie his portrait to that of others on the page in a format reminiscent of a family tree. Tumbling across the page and cavorting through the foliage is a multitude of black devils with horns and twisting pointed tails. In sharp contrast to the multicoloured butterflies and small animals that are to be found on the other pages of the album, the devils that decorate the genealogical display of portraits of members of the legal establishment suggest a playful counter-narrative to the display of these eminent individuals.

Before examining the display of portraits that are to be found in the pages of the albums, it is important to dwell for a short while on the external features of carte albums. Scholars have noted that a common characteristic of carte albums is the way in which were designed to look like a family bible. The Victorian family bible tended to be substantial volume bound in thick tooled leather. One of its functions was to be the place in which the family's genealogy was recorded for posterity and put on display. If, in part, the family-bible format suggests the album was a device for putting the curator's immediate kinship and social network on display, the curatorial process was not limited to these imagined communities. Albums also provided opportunities for the curator to construct and display a network of relations that involved what Batchen describes as ‘flights of fancy and expressions of sentiment’ (Reference Batchen, Long, Noble and Welch2009, p. 92). In general, the carte album was a vehicle for the visualisation of an imagined community and the curator's position within it (Batchen, Reference Batchen, Long, Noble and Welch2009, p. 91).

Viewing the album provided opportunities to identify sitters, remember them and gossip about their relationships and activities. Albums became a feature of many households from the aristocracy to the lower middle classes (Hargreaves, Reference Hargreaves, Hamilton and Hargreaves2001, p. 8). The three albums considered below provide opportunities to examine three different imagined communities that incorporated carte portraits of judges.

6 The Effie Chitty album

Donated to the library of Lincoln's Inn in 2012, the name ‘Effie Chitty’Footnote 23 and the date ‘1900’ appear on the album's inner binding. Effie Chitty was born in 1866. As some of the carte portraits date from around the time of her birth and the ten or so years that follow, she is unlikely to have been the originator of the album. The album has many of the physical characteristics associated with the family-bible format. Measuring 27 by 20 centimetres, the binding is thick dark-green leather tooled into a raised design that resembles a decorated frame. A brass clasp keeps the forty-eight gilt-edged pages together when closed. Each frame cut into the page has a gilded line around it. The album contains 135 portraits.Footnote 24

Hand-written captions under each portrait, all of which appear to be in the same hand, offer evidence of the organising system that shapes the imagined community that the portraits visualise. The first page is made up of a double display of ‘Grandfather’ and matching ‘Grandmother’ portraits: one Chitty, the other Pollock. Page 2 contains a full-body portrait ‘Mother C, Jessie Chitty’ (Effie's mother). ‘Arthur J. Chitty’ and ‘Helena L Chitty’, two of Effie's siblings, are displayed on pages 2 and 3, respectively. The album continues in this manner: ‘Grandfather’, ‘Grandmother’, ‘Mother’, ‘Aunt’ and ‘Uncle’ are scattered throughout the album as a whole. Sitters cross a wide range of ages: from babies and teenagers to sitters in the final years of their life. This is very much a family album – a genealogical display.

Various family members were legal professionals, including judges. Her father, Sir Joseph William Chitty, enjoyed a successful career at the Bar and was appointed a judge of the High Court in 1881 (Rigg, Reference Rigg2004a). Her mother, Jessie, was the daughter of an eminent judge, Sir Jonathan Frederick Pollock, who was Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer (1844–66), and his second wife, Sarah Ann Amowah (Rigg, Reference Rigg and Polden2004b). Holborn (Reference Holborn2013) describes the Chitty and Pollock families as two of the best-known nineteenth-century legal dynasties.

The album has only one portrait of Effie's father, Sir Joseph William Chitty. It appears on page 6 without a caption. Showing his upper body, he wears civilian clothing: a top hat, overcoat and gloves. He poses as if reading a newspaper. His portrait is adjacent to a double portrait of his parents.

The portrait of Joseph Chitty, like the others on the page, probably dates from the early 1870s.Footnote 25 It depicts him as the embodiment of bourgeois respectability. Portraits of him dressed in the ceremonial robes of judicial office do exist but they are not in carte format: he was not appointed to judicial office until the fashion for the carte format had been superseded.Footnote 26 Displayed opposite his parents, its position emphasises the portrait's family meaning and genealogical significance.

Above, in the top left, is a portrait of a man dressed in judicial regalia including a full-bottom wig.Footnote 27 The accompanying caption reads ‘Baron Martin (Uncle Sam)’. It blends together institutional and family positions. Samuel Martin was appointed to the post of judge of the Exchequer Court, ‘Baron Martin’, in 1850, where he remained until his retirement in 1874. He was uncle, ‘Uncle Sam’, to Effie Chitty by marriage. His wife was Frances, the eldest daughter of Sir Frederick Pollock, and his second wife a sister to Effie's mother. The display blends and integrates his institutional status emphasised by the portrait's composition into the genealogical themes of the family album.

The sitter most frequently represented in the album, appearing in eight portraits, is ‘Sir Frederick Pollock’.Footnote 28 He held high judicial office – Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer – for over twenty years, retiring two years before his death in 1870. His dominant position echoes the major role he (and his two wives)Footnote 29 played in populating the Pollock dynasty: he was father of over twenty children. All the portraits show him as a man in his later years: he was in his eighties at the height of the popularity of carte portraits. In seven of the portraits, he wears civilian clothing in a variety of poses; in some he sits, in others he stands. The remaining portrait, a cameo composition, shows little more than his head in profile. He is wearing the full-bottom wig and his chain of office and judicial robes are visible. His pose is one of inner reflection. With one exception, the captions that accompany these portraits, ‘Grandfather’, emphasise their family meaning. Their display also visualises this. On two occasions, pages 12 and 38, his portrait adjoins one of his second wife. Page 4, a page devoted to him, is a homage to this dynastic significance, ‘4 of Grandfather’, and a reference to the curator's position within that dynasty.Footnote 30

The portrait in which he wears judicial regalia is his final appearance in the album. His retirement from judicial office in 1868 suggests the portrait predates that event, making it one of the earliest portraits in the album. With the exception of the different costume, the composition is the same as a cameo portrait displayed on page 45. Both carte portraits were produced by the same studio: John and Charles Watkins. The robed cameo portrait is mounted opposite a carte of his brother, Sir George Pollock, also dressed in robes of office: the military regalia associated with the position of Field Marshal. The respective captions are more formal: ‘Sir Frederick Pollock’ and ‘Field Marshall Sir George Pollock’. While the carte portrait of Sir Frederick Pollock in his judicial robes of office does stand out from the other portraits in the album, like the portrait of ‘Baron Martin’, it is not out of place in a family album and a display devoted to genealogical. It is woven into it. If the multiple appearances of Sir Frederick give visual form to his dynastic significance, the final cameo celebrates and adds the value that comes from his institutional status to the domestic dynastic community displayed in and through the album's pages.Footnote 31

7 ‘Album 2’

Little is known about the provenance of the next album. It was donated to Lincoln's Inn late in the twentieth century by the Law Society of England and Wales. It is catalogued as ‘Album 2’. Of similar size and style to the Effie Chitty album, its thirty-four pages contain ninety-one carte portraits and two larger cabinet-card portraits; some pages have empty mounts. The portraits date from the 1860s to the 1880s.

The family organised and displayed in this album is different. It is all male. All its members are adults. The accompanying captions reference each sitter's legal institutional position. Eighty-two are identified as judicial office-holders.Footnote 32 The captions suggest that the family on display here is made up of relations between legal institutional office-holders.

On closer inspection, the album's display appears to be in two parts. The first part, with sixteen portraits (several of the mounts in this part are empty), runs from pages 1 to 9. This is followed by sixty-six that fill the remaining pages.

The opening page of the album stands apart. While it has the usual carte-sized mounts cut into its surface, two larger-format cabinet-card portraits (108 by 165 millimetres (4.25 by 6.5 inches)) have been pasted over the original mounts. In composition, they are much like the two carte portraits displayed below them and in the rest of the album. Both are upper-body portraits with the head angled: one to the left, the other to the right; both show the sitters wearing a bench wig dressed in black judicial robes. Each has a caption integrated into the picture: ‘Mr Justice Day’ and ‘Mr Justice Wills’. Both the format and the captions indicate that these portraits post date all the others in the album: ‘Mr Justice Day’ (John Charles Day) was appointed to that post in 1882, ‘Mr Justice Wills’ (Alfred Wills) in 1884. These sitters also appear later (page 6) in carte portraits, looking younger, dressed in the robes and wigs of a barrister. The caption under the second Wills portrait reads ‘Alfred Wills QC’. That under Day's portrait repeats his later institutional title: ‘Mr Justice Day’. Both were appointed as Q.C. (Queens Counsel) in 1872. In common with the rest of the album, the captions make reference to the sitter's professional status, but the institutional title does not always match the sitter's costume.

One way of making sense of the first part of the album is by turning to the second part. The reason for this is that, starting on page 10, a clear organising theme is apparent: legal institutional hierarchy. It begins with portraits of sitters identified as Lord Chancellors. The pages that follow group together Lord Chief Justices,Footnote 33 followed by those who held the office of Master of the Rolls, Lord Justices and Justices of various divisions of the High Court.Footnote 34 The final pages display portraits of senior law officers: Attorneys General, Solicitor Generals and Queen's Counsel. Each institutional category provides an opportunity to show the genealogy of that office. For example, the eight portraits of Lord Chancellors include two, of Lord Brougham and Lyndhurst, who held office prior to the invention of carte portraits but who, in the 1860s, remained eminent figures at least in part by virtue of that office. Lyndhurst, whose portrait is first in the sequence, died in 1863; the second, Lord Brougham, died in 1868. In contrast, the first section is more idiosyncratic, more personal and the legibility of the system is now difficult to decipher. But its priority over the use of portraits in a display of legal institutional hierarchy suggests it had particular significance for the album's curator.

Do the album's organising themes, of professional relations and institutional hierarchy, break with the family and genealogical dynamics of carte albums? In short, the answer is ‘no’. The ‘Effie Chitty’ album illustrates that biological family ties and legal professional ties are not mutually exclusive. In Album 2, the family/professional relationship is inverted; legal professional and institutional relations that are displayed as family relations. Metaphors of family relations are commonplace in the interrelationships that make up legal professional communities (Moran, Reference Moran2011).Footnote 35 Lord Chancellors followed by Chief Justices then High Court judges, Q.C.s and so on is a display of the curator's institutional ‘great grandfathers’, ‘grandfathers’, ‘fathers’, ‘uncles’ and ‘brothers’ in law. Professional social networks are a form of kinship – a set of relationships through which the members negotiate the trials and tribulations of their professional life course (Butler, Reference Butler2002). The fact that all the sitters are adult men does not disrupt the familial and the genealogical themes of the album. The portraits put it on display and show it to be a homosocial phenomenon in which men are central to the production and reproduction of the legal professional world. If the Effie Chitty album domesticates judicial portraits, weaving them into a display that is devoted to the representation of biological domestic family relations, then Album 2 offers an example of the way portraits of judges function as family portraits for a rather different imagined community of family members.

Before leaving Album 2, I want to highlight one more feature of the portraits and their display. The majority of the carte portraits of judicial office-holders show the sitter not in robes of office, but in civilian dress. They share much in common with the portrait of Lord Cockburn above (Figure 2). The repetitive nature of the poses and overall compositions can in part be explained by the technical limitations of photography at the time and the procedures used by the studios to produce carte portraits (Perry, Reference Perry2012, p. 729). But the repetitive and predictable aesthetic also has social and political significance. It is not something that sitters attempted to avoid, but more an aesthetics of choice that was engaged as a part of their self-performance and self-staging of bourgeois identity (Batchen, Reference Batchen, Long, Noble and Welch2009, p. 86). Individually and collectively, they display what Perry describes as the ‘surplus of ordinariness’ (Reference Perry2012, p. 728) – that is, the manner of bourgeois respectability that was the fashion at the time.Footnote 36 Album 2 puts the legal professional investment in this ordinariness on display and shows how it has been integrated into the curator's sense of belonging in the legal professional family.

8 The ‘Tichborne claimant album’

The final album is catalogued in the NPG's collection as ‘The Tichborne Claimant Trial Album: cartes-de-visite by various photographers, 1860s–1870s’ (Unknown, undated). Its fifty pages contain 148 carte portraits. It was purchased by the gallery in 1984 from Eric Horne, who inherited it from his grandmother, who purchased it at an auction sometime after the World War I.Footnote 37 The seller speculated that it was originally owned by a member of the Tyndall family,Footnote 38 who had connections with the Tichbornes.

The title given to the album refers to a legal dispute that has been described as the greatest cause célèbre of the Victorian age (McWilliam, Reference McWilliam2007). The dispute related to the Tichborne title and estates. Roger Tichborne, the rightful heir, left England in 1853 for South America and was thought to have been lost at sea in 1854. In August 1865, Arthur Orton, who was then living in the country town of Wagga Wagga in New South Wales, Australia, claimed he was the long-lost heir. His long and complicated campaign to claim the title and property ran from 1867 to 1874. It culminated in two court cases: a civil case to establish his claim and a second criminal case in which he was charged with and found guilty of perjury (Annear, Reference Annear2002). The media frenzy and popular interest turned these cases into two of the best-known courtroom disputes of the nineteenth century (Tucker, Reference Tucker, Mitman and Wilder2016).

But calling this album after these legal proceedings is misleading. The majority of portraits in the album have no connection with the Tichborne case. Those that do are confined to nine of the fifty pages of the album. It begins with the portraits of the lost heir, the claimant and key family members of their respective families. Other portraits are of barristers involved in the cases, and key witnesses and eminent figures who supported the parties. One carte is a group portrait of the members of the jury from the second criminal trial. Fourteen of the portraits in this section are of judges; twelve are in the style of ‘state portraits’ of judges. Before examining the display of these portraits of judges in the Tichborne section in more detail, I want to consider their place in the organisation of the album as a whole.

Like the other albums, its binding references the usual associations with ‘family’ and ‘genealogy’. Its etched, red-leather covers are embellished with a number of brass fittings: edgings, twin clasps and interwoven letters ‘C’, ‘A’ and ‘T’. But, from its opening pages, its content seems to have little to do with these types of relationships. It begins with two portraits of Queen Victoria: both photographic reproductions of earlier graphic portraits – one that dates from 1825 and the other from 1837. The following pages display portraits of aristocrats, both domestic and European, followed by religious figures, including the Pope and the Bishop of London (John Jackson), and famous figures such as Florence Nightingale. The bulk of the album (over 50 per cent) is made up of portraits of writers, artists, actors, actresses and female opera singers.

The longer history of collecting reproductions of portraits and making albums of them helps to shed some light on this display. In the eighteenth century, it became a fashionable pastime for wealthy males to collect reproductions of portraits and to organise their display in albums (Pointon, Reference Pointon1993). James Granger published a book that set out a system of display for album-makers to follow. The title of his book, A Biographical History of England from Egbert the Great the Revolution: Consisting of Characters Disposed in Different Classes and Adapted to a Methodical Catalogue of Engraved British Head Intended as an Essay towards Reducing Biography to System, and a Help to the Knowledge of Portraits, with a Preface Showing the Utility of a Collection of Engraved Portraits to Supply the Defect and Answer the Various Purposes of Medals (Granger, Reference Granger1769), draws attention to the organising themes of his system of display. One is social hierarchy. The genealogy of that social hierarchy is another. At the top of this hierarchy is royalty. Ten other rankings follow: the lowest is ‘Persons of both Sexes, chiefly of the lowest Order of the People, remarkable for only one Circumstance in their Lives; namely such as lived to a great Age, deformed Persons, Convicts, &c.’ (quoted in Pointon, Reference Pointon1993, p. 56). Granger's system classifies society by way of a range of categories of ‘well-knownness’, or ‘renown’ (Kornmeier, Reference Kornmeier2008, p. 278). It does this by reference to a hierarchy of public visibility linked to public recognition, reputation or significance – what van Krieken (Reference van Krieken2012) describes as attention capital. The value of the attention attached to the highest category is closely associated with its longevity and its institutionalisation. That association with the lowest is more quixotic, idiosyncratic, lacking in substance and legitimacy.

A ‘Grangerised book’ is one in which the organisation of visual images displayed follows this system. The Tichborne album has all the hallmarks of a ‘Grangerised book’. The result is an imagined community that is different from the other albums considered here. Its range and diversity suggest that, in all likelihood, it stretches way beyond the curator's biological, domestic or professional family. A contemporary description of carte albums from the nineteenth-century publication Art Journal is that they are a ‘family portrait of the entire community’ (Plunkett, Reference Plunkett2003a, p. 61).

This captures well the range of sitters in the Tichborne album as a whole. Queen Victoria is the ‘mother’ of the entire community of the time. The highest officers of state court officers and senior aristocrats are the respected avuncular figures and elder siblings. Sporting heroes, opera singers and music-hall performers are the more artistic and creative relatives.

The location of the carte portraits of judges in the Tichborne album fits this scheme of things. The fourteen portraits of judges occupy a position in the album consistent with their ranking within Granger's imagined hierarchical community: coming after the clergy and before senior politicians. Displayed in this location, the portraits show them as the fathers and brothers ‘in law’ of the whole community. However, the Tichborne subset in which the judges appear actually disrupts the hierarchy that shapes the larger distribution of portraits.

The subset opens not with a portrait of the highest-ranking judge, but with portraits of the absent aristocrat at the centre of the litigation and the claimant – at the time, a working-class, down-at-heel butcher from rural Australia. The working-class butcher appears a second time on the last page of the section, this time as ‘The Prisoner’. When the judges do appear, the logic of their display is far from clear, as their display does not seem to follow the usual rules of institutional value. Chief Justice Cockburn and senior trial judges appear before the portrait of the Lord Chancellor Roundell Palmer, who held that position during the litigation, between 1872 and 1874. How are we to make sense of the display that makes up the Tichborne section?

The display of portraits visualises a sensational courtroom drama. The curator has organised them according to the requirements of a dark romance of the landed gentry in battle against the corrupting forces of the working-class attempt to seize their lands and title. The opening display of the lost heir and the claimant starts the story rolling. The closing display of the claimant as ‘The Prisoner’, his wife and his two crucial now discredited witnessesFootnote 39 shows the just deserts that follow the restoration of the status quo. The display shows the disruption of the ranking of visibility that a social drama being played out in and through the legal process and reported in the media might have.

Judicial portraits appear as ‘characters’ in this story. But the order of their appearance does not quite fit this scheme of things. Cockburn, who was one of the judges in the second criminal trial, appears too early in the story and before the judge who presided over the first trial, the civil case, Sir William Bovill. One explanation for this might be Cockburn's pre-existing attention capital. In his long judicial career, he had been involved in many cases that attracted lots of media attention. He ‘relished the limelight’ (Lobban, Reference Lobban2004).Footnote 40 He certainly had ample opportunity to develop his media profile in the 188 days of the criminal trial of the Tichborne claimant. He gave an extravagant judicial performance with the delivery of an 800-page summary of the second trial. It filled the pages of the newspapers for eighteen days. He later went on to publish it as a book. McWilliam (Reference McWilliam2007, p. 105) describes it as one of the great sensation novels of the day.

Before leaving this album, I want to make a brief comment about the other portraits of judges in the Tichborne section. While all were active at the time of the Tichborne dispute, the majority do not appear to have had a direct connection with those proceedings. If their appearance at this point makes sense in terms of Granger's rankings of a tradition of public visibility, their distribution in and amongst the other characters involved in courtroom drama that made up the ‘trial of the century’ puts on display the link between their visibility and the changing landscape of celebrity. As Tucker notes, cartes de visite in general and the London Stereographic and Photographic Company studio in particular played an important role in making the Tichborne legal proceedings a visual spectacle for all to see and its main characters celebrities (Tucker, Reference Tucker, Mitman and Wilder2016).

9 Conclusion

This study takes research on the relationship between judges, photography and the mass media in a new direction, adding a new dimension. It explores the birth of the photographic image of the senior judiciary in the mid-nineteenth century. In doing so, it begins to close the gap between the birth of photography as a form of mass media and first appearances of photographic images of the judiciary in news print at the beginning of the twentieth century. Unlike graphic and later photographic images of courtroom proceedings in which the judge tends to be a marginal character, the carte de visite portraits put the judges at the centre of the picture. Now largely forgotten, this study brings these pictures back into view and offers an analysis of their nature and cultural significance.

The examples considered here are typical of carte portraits of judicial sitters. In many respects, what appears within the frame indicates that they are unremarkable portraits. Those that follow what I have described as the tradition of state portraiture follow a long-standing aesthetic convention through which the individual office-holder is depicted through a set of symbols associated with the office as the embodiment of its values and virtues. In others, the sitter fashions and presents himself according to more recent aesthetics of bourgeois respectability. Carte portraits provided cheaper, quicker and more easily available opportunities for those in judicial office to not only have access to their own image, but also to circulate it. While the subjects of these portraits were in part responsible for their production, studios also played a key role in commissioning these portraits with a view to selling them to the public.

At the time the carte portraits first appeared, they had great novelty. They offered viewers the most accurate representations of the physical likeness of the senior members of the judiciary. While contemporaries were critical of this ‘warts and all’ quality, it was a feature of these portraits that introduced a new set of signs through which the values and virtues of judicial office might be represented: openness, transparency and authenticity. Their incorporation into portraits of authority figures was not unique to the judiciary, but indicative of wider changes taking place in the signs used in the depiction of figures of authority.

Another other important dimension of this change is the opportunities carte portraits provided for viewers to experience mediated quasi interactions with senior judicial office-holders. Of particular interest here are the experiences of proximity to and intimacy with figures of authority such as the judiciary. These photographic portraits made the extraordinary, such as royalty and the senior judiciary, appear more ordinary. In this context, ‘ordinary’ has strong class overtones – being associated with bourgeois respectability.

Making the extraordinary figure of the elite judge more ordinary also needs to be juxtaposed with another dimension of the changes that the carte phenomenon engaged. They played a role in making the ordinary into the extraordinary. The reduced cost of portraiture and the entrepreneurial zeal of the studios not only widened access to portraiture of royalty, aristocrats and senior judges (all of whom had already made use of portraiture), but it also created new opportunities for public visibility for a much wider range of people. The display of judicial carte portraits in the Tichborne album illustrates this point. The sitters gathered together in the Tichborne section of that album offer examples of the carte portraits of ordinary subjects made extraordinary: butchers, ex-slaves, otherwise invisible members of the working class. In the pages of the album, they rub shoulders with aristocrats, senior judicial officers and elite politicians. ‘Celebrity’ is a term that points to this process of expanding public visibility of individuals. If carte portraits allowed judges to further grow their visibility, ostensibly based on the importance of their role in society, it is a form of picture that also increased the competition in the market-place of visibility.

The three albums provide an opportunity to examine three different contexts in which carte portraits of judges contributed to making and making the meaning of three nineteenth-century imagined communities of various sizes and scales. They offer three examples of the ways in which carte de visit pictures of judges were embedded in community formations. Common to all three is the idea of the use of portraiture and its display to fashion community as a set of social relations through which identity is formed and belonging is created. The difference between them lies in the shape and scope of the imagined communities formed and put on display in these albums. In the Effie Chitty album, the pictures of judges are made sense of as characters in a network of domestic kinship whose institutional status adds value to the kinship community in general and the curator's position within it in particular. In Album 2, the curator uses portraits of judicial office-holders to shape and put on display a different network of ‘family relations’: legal professional relations. Last, but by no means least, in the Tichborne album, the curator integrates portraits of judges into a display of the imagined community of civil society. In the section devoted to the trials of the century, the attention capital of senior judicial office-holders that Granger captured in his system of rankings is being challenged. They now jostle for position, at least temporarily, with the minor celebrities made through the media reports of the courtroom narratives that became so popular. All three albums draw attention to the important role played by the viewer in making the meaning of the carte portraits of judges.