1. Introduction

Several recent studies have investigated an ongoing change in the grammatical system of Norwegian, where some dialects have been shown to be in the process of changing from a three-gender system to a system with only two genders, for example, Oslo (Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011a,b, Lundquist & Vangsnes 2018), including the urban ethnolect (Opsahl 2009), Kåfjord, Nordreisa, and Finnmark dialects (Conzett et al. 2011, Stabell Reference Stabell2016), Tromsø (Rodina & Westergaard 2015, Lundquist et al. 2016), and Trondheim (Busterud et al. 2019). While the traditional gender system distinguishes between masculine, feminine, and neuter, as in 1a, the new gender system illustrated in 1b lacks feminine agreement forms, preserving only a distinction between the neuter and what may be referred to as common gender.

(1)

This change results in a somewhat more complex declension system expressed on suffixed definite articles, which generally retain the traditional feminine form (but see below for certain exceptions). In the new two-gender system, common gender nouns have two declension paradigms, one for masculine nouns and another for previously feminine nouns, as illustrated in 2a and 2b, respectively. Neuter nouns remain unchanged, as in 2c.

(2)

The current loss of the feminine gender across a number of dialects is argued to be caused by sociolinguistic factors, such as language contact in certain areas in North Norway (Conzett et al. 2011) or the influence of a high-prestige variety of Norwegian spoken in Western Oslo (Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011a,b, Lundquist et al. 2016, Lundquist & Vangsnes 2018). In a recent investigation comparing the status of feminine in the dialects of Trondheim and Tromsø (Busterud et al. 2019), it has been suggested that the high prestige of the Western Oslo dialect may also explain why the change is more advanced in urban dialects (often referred to as city jumping in the sociolinguistic literature; see Taeldeman Reference Taeldeman, Auer, Hinskens and Kerswill2005; Trudgill Reference Trudgill1974, Reference Trudgill1983; Vandekerckhove Reference Vandekerckhove2009). Lundquist et al. (2016) and Lundquist & Vangsnes (2018) also highlight Norwegian speakers’ constant exposure to variation within their language, which may lead to unstable production of the feminine indefinite article ei across different dialects.

The claim that the feminine is being lost is largely based on the disappearance of the indefinite article ei ‘a’. However, this could, in principle, be a change affecting a single feminine form rather than the whole feminine gender category altogether. That is, this could simply be an extension of the syncretism that already exists between masculine and feminine forms (see the next section), rather than the loss of feminine gender. In traditional three-gender dialects, there is only one other unambiguously feminine category, the possessive, which may be either pre- or postnominal. According to recent analyses, pre- and postnominal possessives differ in that only the former are exponents of gender (Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011b, Svenonius Reference Svenonius, Gribanova and Stephanie2017).

Possessives have so far not been studied systematically. Therefore, in the present study we conduct a cross-sectional empirical investigation of gender marking in indefinite as well as possessive noun phrases in the Tromsø dialect, across five age groups. We consider speaker preferences for two unambiguously feminine forms, indefinite ei ‘a’ and 1st person singular possessive mi ‘my’. Furthermore, we compare pre- and postnominal possessives and investigate the status of the latter in relation to the feminine definite suffix -a, thus addressing possible consequences of the loss of feminine gender for the declension system of Norwegian.

The structure of the paper is as follows: The next section provides some relevant background on gender in Norwegian and the Tromsø dialect in particular, focusing on the structure of possessives and some previous research. Section 3 introduces the current study, including research questions and methodology, while section 4 gives an overview of the results, which generally confirm that the feminine gender is being lost. Section 5 provides a discussion, focusing on gender versus declension class, and section 6 is a brief summary and conclusion.

2. Background

2.1. The Traditional Three-Gender System of Norwegian

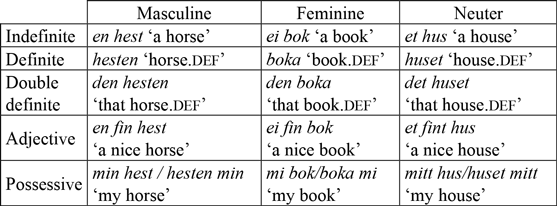

While many other Germanic languages—for example, Dutch or Danish—have lost the feminine gender, Norwegian dialects have traditionally retained the three-gender system of Old Norse, with the exception of the Bergen dialect, which lost the feminine gender in the 14th century, arguably due to contact with Low German during the Hansa period (Jahr Reference Jahr1998, Reference Jahr2001; Trudgill Reference Trudgill and Lohndal2013). The traditional three-gender system of many Norwegian dialects is displayed in table 1, illustrating indefinite and definite forms (the latter expressed as a suffix), as well as adjectives, pre- and postnominal possessives, and so-called double definites (which are required when the noun phrase is either demonstrative or modified, as in det store huset ‘the big house.def’).

Table 1. The traditional three-gender system in many varieties of Norwegian.

One striking property of the Norwegian gender system is the extensive syncretism between masculine and feminine forms. As illustrated in table 1, the syncretism applies to adjectives, as in fin ‘nice.m/f’ versus fint ‘nice.n’ and the prenominal determiner in the double definite form, as in den (m/f) versus det (n). Further examples, not illustrated in the table, include demonstratives, as in denne hesten/boka ‘this horse.m/book.f’ versus dette huset ‘this house.n’, and quantifiers, as in all maten/suppa ‘all the food.m/soup.f’ versus alt rotet ‘all the mess.n’. These syncretic forms are also characteristic of the Tromsø dialect, which means that, like other dialects of Norwegian, this dialect has very few exponents of feminine gender. In addition to the indefinite article illustrated in table 1, there is only one adjective (meaning ‘little’) that shows no syncretism: liten(m)–lita (f)–lite(n) as well as some of the possessives: 1st person singular (min–mi–mitt ‘my.m/f/n’), 2nd person singular (din–di–ditt ‘your.m/f/n’), and 3rd person reflexive possessives (sin MASC, si FEM, sitt NEUT ‘her, his, their’).Footnote 1 Many traditional dialects use the personal pronouns ho ‘she’ and han ‘he’ for inanimate nouns, as in French or German, for example. While we are not aware of any systematic study of this phenomenon, it is our impression that pronominal ho and han for inanimates are virtually nonexistent in the present-day Tromsø dialect, at least among young speakers. Thus, the 3rd person pronoun ho ‘she’ is mainly used to refer to biologically female animates. This means that there are very few unambiguously feminine forms across different dialects of Norwegian (including Tromsø), mainly the indefinite article ei and the above-mentioned possessives (mi ‘my’, di ‘your’, and the reflexive si ‘her, his, their’).

In this article, we adopt the relatively standard definition of gender expressed in Hockett Reference Hockett1958:231, according to which “[g]enders are classes of nouns reflected in the behavior of associated words.” This means that gender is a morphosyntactic feature expressing agreement between the noun and other words, such as determiners, adjectives, etc. This view of agreement as the defining property of gender is widely accepted today (see Comrie Reference Comrie1999, Audring Reference Audring2014 among others). By contrast, affixes on the noun itself are considered to be part of the declension paradigm. Thus, although affixes may differ across noun classes (and therefore across genders), they are not themselves exponents of gender (Corbett Reference Corbett1991:146). On this definition of gender, the definite suffix in Norwegian does not express gender, but is a declension class marker. However, the definite suffix has traditionally been considered to be a gender marker in Norwegian grammar (see, for example, Faarlund et al. 1997). We believe that there is good reason to consider the indefinite article and the definite suffix as different with respect to gender exponence, as the two forms behave differently both in language acquisition and language change. For example, definite suffixes are in place considerably earlier than indefinite articles in Norwegian child language (Rodina & Westergaard 2013a,b). Furthermore, Lødrup (Reference Lødrup2011a), Conzett et al. (2011), and Rodina & Westergaard (2015) have shown that a change in the indefinite article typically does not affect the definite suffix. This has also been attested in Norwegian heritage language (Lohndal & Westergaard 2016). The evidence from acquisition and change indicates that the form of the indefinite article is determined by gender, while the form of the definite suffix is determined by declension class.

Norwegian definite and indefinite plural forms are also expressed by suffixes (including a null suffix in the indefinite form of many neuter nouns), and in many dialects there are distinct plurals generally corresponding to the three genders. For example, the Tromsø dialect has the following forms for masculine, feminine, and neuter, respectively: hesta–hestan ‘horses.indf.pl/def.pl’, nåle–nålen ‘needles.indf.pl/ def.pl’, hus–husan ‘houses.indf.pl/def.pl’. However, there is consider-able variation across dialects, and the correspondence between gender and plural forms is weak at best. Thus, to our knowledge, nobody has argued that plurals in Norwegian are exponents of gender (see Enger Reference Enger2004, Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011a, Rodina & Westergaard 2013a).

Finally, it should be noted that gender assignment is relatively non-transparent in Norwegian. Trosterud (Reference Trosterud2001) has nevertheless identified as many as 43 rules for gender assignment, but these have many exceptions and may only be considered to be tendencies. One such tendency assumed to have considerable predictive power is observed in disyllabic nouns ending in -e, which are often feminine (that is, the class of so-called weak feminines), such as ei bøtte ‘a bucket’, ei skjorte ‘a shirt’.Footnote 2 However, some recent studies using nonce words indicate that the predictive power of this tendency is relatively weak (Gagliardi Reference Gagliardi2012, Urek et al. forthcoming).

2.2. The Status of the Feminine in the Tromsø Dialect

Rodina & Westergaard (2015) argue that there is an ongoing historical change in the Tromsø dialect involving the loss of feminine gender agreement. This argument is based on a study showing that young children and teenagers hardly use the feminine indefinite article ei, replacing it by the masculine form en. The study examines indefinites in five groups of participants: preschool children (group 1), 2nd graders (group 2), 7th graders (group 3), adolescents (group 4), and adults (group 5). Feminine indefinite ei was infrequently attested in the data from preschoolers and elementary school children (groups 1, 2, and 3), making up only 7–15% of responses. In contrast, adults were found to use ei 99% of the time. Adolescents’ use of ei amounted to 56% of their responses, which was significantly different from both children and adults. This was the only participant group that displayed a considerable amount of variation, as approximately half of the group used feminine ei consistent-ly and the rest of the group used ei and en interchangeably across all (feminine) test nouns.

Despite the observed changes in the agreement form, Rodina & Westergaard (2015) show that these (previously) feminine nouns retained the suffixal definite article -a, as this form was used by all participant groups between 89% and 99% of the time. Thus, the authors argue that the new two-gender system of the Tromsø dialect is characterized by an added complexity in the declension system, as common gender nouns now have two declension patterns, one corresponding to the originally masculine nouns and the other to the originally feminine nouns, as shown above in 2a,b. Thus, the number of inflectional classes is larger than the number of genders, which conforms to the gender-declension relation-ship observed across various other languages (see, among others, Corbett Reference Corbett1982, Wechsler & Zlatić 2000, Enger Reference Enger2004).

A slightly different picture has been reported for the suffixed definite forms of traditionally feminine nouns in studies investigating the dialects of Trondheim and Oslo (Busterud et al. 2019, Lundquist & Vangsnes 2018). Busterud et al. (2019) show that in Trondheim, previously feminine nouns occasionally appear with the masculine -en suffix instead of the traditional -a form, suggesting that there may also be an incipient change in the declension system. The -en form with the feminines is found 23% and 11% of the time in the two youngest age groups, and 13% of the time in the production of the adults, but no participant is reported to use the -en form consistently.Footnote 3 Busterud et al. (2019) also show that the Trondheim change in the indefinites is somewhat more advanced than in Tromsø, in that even adult Trondheim speakers use feminine ei infrequently (35% of the time) in contrast to adult Tromsø speakers, who are productive users of ei (99%), according to Rodina & Westergaard 2015. The change in the declension class system appears to be even more pronounced in the Oslo dialect.Footnote 4 In Lundquist & Vangsnes 2018, 10 out of 33 participants aged 17–18 are shown to consistently use the masculine definite suffix, 10 others consistently use the feminine definite suffix, and the remaining three switch between masculine and feminine. It should be noted that there is nevertheless a considerable distinction between the suffixes and gender forms, as the majority of the participants (27 out of 33) consistently used the masculine indefinite article with previously feminine nouns, and the authors conclude that feminine gender no longer exists as a category for most young Oslo speakers.

As stated in Introduction, various sociolinguistic phenomena may have been instrumental in bringing about the change in the gender system of Norwegian dialects. The nature of the change is nevertheless attributed to several language-internal factors. According to Rodina & Westergaard 2015, one of the major factors explaining the loss of the feminine gender is the syncretism between masculine and feminine across various agreement forms, as discussed in the previous section. Frequency is shown to play an additional role in the competition between masculine and feminine, as masculine is reported to be massively more frequent than feminine (as well as neuter), both in the language as a whole and in the input to children: Based on a total of 31,500 nouns in the Nynorsk Dictionary, Trosterud (Reference Trosterud2001) has found that masculine nouns make up 52%, while feminine nouns constitute 32% and neuter nouns only 16%. Furthermore, based on a sample of child-directed speech, Rodina & Westergaard (2015) show that the token frequency of the masculine indefinite article en is as high as 62.9% (1,866/2,980), while the feminine and neuter forms ei and et are represented 18.9% (563/2,980) and 18.5% (551/2,980), respectively. Finally, the different behavior of indefinite articles and definite suffixes may be due to the latter being acquired very early (around the age of 2–3, see Anderssen Reference Anderssen2006, Rodina & Westergaard 2013a,b), while the former are often not produced target-consistently until approximately the age of 6–7 (Rodina & Westergaard 2015).

2.3. The Structure of Possessives in Norwegian

As mentioned above, possessives can be either pre- or postnominal in Norwegian, as shown in 3a,b (see, among others, Faarlund Reference Faarlund2019). Nouns obligatorily have indefinite morphology with prenominal possessives and definite morphology with postnominal possessives. The main difference between the two possessive constructions is that the prenominal one has a marked, contrastive interpretation, while the postnominal one is more neutral. For this reason, the postnominal possessive is also the more frequent construction, making up approximately 75% of all possessives in spontaneous production (Anderssen & Westergaard 2010). An in-depth investigation of the properties of Norwegian pre- and postnominal possessives offered in Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011b emphasizes the strong-weak pronominal distinction, where pre- and postnominal possessives are shown to have properties of strong and weak pronouns, respectively. For the discussion of gender presented below it is important to keep in mind that postnominal possessives always, without exception, immediately follow a noun with the definite suffix.

(3)

Only three possessive forms unambiguously mark a masculine-feminine-neuter distinction: 1st person singular (min–mi–mitt ‘my.m/f/n’), 2nd person singular (din–di–ditt ‘your.m/f/n’), and 3rd person reflexive possessives (sin, si, sitt ‘his, her, their’). The traditional three-gender distinction is illustrated in 4 for the 1st person singular forms.

(4)

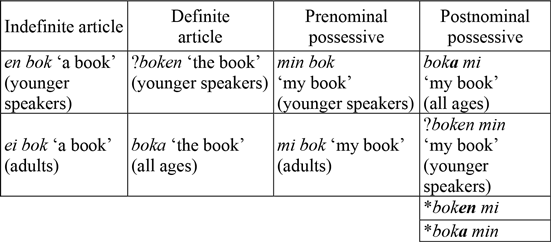

A somewhat different pattern is reported for Western Oslo: According to Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011b, feminine forms such as mi ‘my’ are not used in prenominal position, as in 5a, but they are retained in postnominal possessives, illustrated in 5b. Importantly, postnominal mi as well as di and si forms can only appear immediately adjacent to an overt noun with the (traditionally feminine) definite suffix -a.

(5)

Lødrup (Reference Lødrup2011b) argues that the -a and mi/di/si forms in postnominal possessives in Western Oslo have no relation to feminine gender. According to Lødrup, they are bound morphemes that are not constrained through agreement. To explain these properties of postnominal possessives, Lødrup (Reference Lødrup2011b) proposes an analysis of the postnominal possessive as a suffix. A similar proposal is found in Trosterud Reference Trosterud2001 and Conzett et al. 2011. According to the suffix analysis, the postnominal mi as well as di and si are not feminine gender forms, but suffixes that reflect the declension properties of the preceding noun. Thus, Western Oslo has suffixal possessives that express declension class and appear obligatorily adjacent to the definite-marked noun.

However, there are several problematic issues with the suffix analysis. For example, Lødrup (Reference Lødrup2011b) notes that the postnominal possessor can scope over coordination, as in 6a, and can be elided, as in 6b (in the latter case, the second possessive will have to appear in the masculine/common form, as it is not adjacent to a definite -a suffix). This behavior is unexpected if the postnominal possessive is a suffix.

(6)

Furthermore, Svenonius (Reference Svenonius, Gribanova and Stephanie2017) points out another problematic issue: The suffix account assumes that the declension class feature should be percolated through the definite suffix and surface on the postnominal possessive, as “there is no particular reason that an affix selecting for a class … should itself behave like a class … for purposes of other allomorphy” (p. 353). As an alternative, he proposes that in two-gender dialects such as Western Oslo, mi, di, and si are allomorphs that are conditioned by the phonological context of the immediately preceding vowel within a prosodic phrase. This proposal is motivated by a broad range of empirical data from other languages. For example, the nominal conjunction in Korean and the Spanish definite article are among many cases of class-based allomorphy within words and across word boundaries. The Spanish example in 7 demonstrates that the definite article immediately preceding a feminine noun starting with a stressed /a/ has the form el typical of masculine nouns and not la used with feminines. In other words, the definite singular el is not an exponent of gender, but an example of allomorphy conditioned by the phonological context. The feminine gender of the noun agua ‘water’ is expressed on the postnominal adjective fría ‘cold’. Thus, the distribution of the prenominal article in Spanish appears to be sensitive to a phonological property of the left edge of the noun.

(7)

Similarly, Norwegian forms such as boka mi ‘my book’ are argued to be cases of class-based allomorphy occurring postnominally. In other words, the use of mi, di, and si forms after nouns ending in the definite singular suffix -a is the result of a process of phonological selection that requires locality of the conditioning environment. Since being vowel-final is a phonetically realized property, it can be visible across a word boundary. This contextual allomorphy account predicts that two-gender dialects should allow forms such as boka mi ‘my book’ for previously feminine nouns, as well as boken min lit. ‘book.def my’, but not the combinations boka min or boken mi.

3. The Present Study: Research Questions and Methodology

3.1. Research Questions and Predictions

The main goal of the present study is to investigate whether the low use of feminine indefinite ei in younger speakers of the Tromsø dialect attested in Rodina & Westergaard 2015 indicates loss of the feminine gender or whether it simply reflects the disappearance of the feminine form ei, resulting in more extensive syncretism in the paradigm (see table 1). To answer this question, it is necessary to consider speaker preferences across several unambiguously feminine forms. As mentioned above, the number of such forms in the (traditional three-gender) Tromsø dialect is limited, and feminine is generally only expressed on the indefinite article ei and the possessive forms mi ‘my’, di ‘your’, and si ‘her, his, their’. If the feminine gender is indeed disappearing, then the pattern of use of these forms should be similar and infrequent in younger speakers. More specifically, we predict that preschoolers, school-aged children, and adolescents will use the feminine gender forms ei and mi less than 50% of the time, and that these forms will be replaced by masculine en and min. In contrast, corresponding to the findings in Rodina & Westergaard 2015, adults are predicted to use ei and mi consistently.

The study also investigates the status of the declension system of traditionally feminine nouns in the Tromsø dialect. Previous research suggests that the singular definite suffix -a is generally not affected by the loss of the feminine gender (see Lødrup 2011 for the Oslo dialect, Conzett et al. 2011 for Northern Troms and Rodina & Westergaard 2015 for the Tromsø dialect). It can thus be predicted that the definite -a forms will remain in use across all participant groups. At the same time, more recent studies have found that the declension system may be undergoing a change as well (Busterud et al. 2019, Lundquist & Vangsnes 2018), although to a considerably lesser extent, which may indicate that it is a separate development. Thus, there is a possibility that the -a forms on previously feminine nouns are beginning to be replaced by -en in the Tromsø dialect.

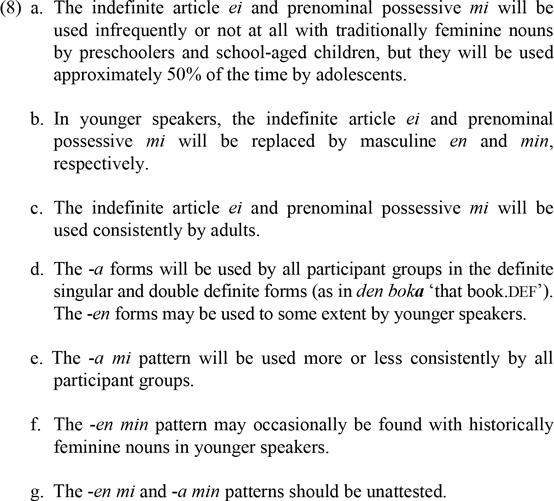

Similarly, for the postnominal possessives we predict that the feminine form mi will be used more or less consistently across all participant groups, and that this will be a direct result of the stability of the -a form. Thus, we generally expect to find the pattern boka mi ‘book.def my’. It is also possible that the -en min pattern (as in boken min) may be found with previously feminine nouns to some extent in younger speakers. However, the patterns -a min (boka min) and -en mi (boken mi), violating contextual allomorphy, should not be found. The predictions for the study are summarized in 8 and table 2.

Table 2. Predictions for the use of indefinite, definite, and possessive forms with previously feminine nouns by speakers of the Tromsø dialect.

(8)

If these predictions are borne out, it will be possible to conclude that the feminine gender is being lost in the Tromsø dialect, as with the disappearance of both the feminine indefinite article and the correspond-ing possessives there will no longer be any productive forms distinguishing the feminine from the masculine gender.

3.2. Participants, Stimuli, and Procedure

To allow comparison with the data in Rodina & Westergaard 2015, we have investigated the use of ei and mi forms in five age groups as specified in table 3: preschoolers, school-aged children in grades 2 and 7, adolescents, and adults. The child participants and adolescents were born in Tromsø and grew up acquiring the local dialect. Some of them had also been exposed to other Norwegian dialects at home. The adult participants were all born in Tromsø and had lived there most of their lives. They were employees at UiT The Arctic University of Norway but had no background in linguistics. It should be noted that the participants in group 4 in the present sample are somewhat younger than the ones in Rodina &Westergaard 2015, that is, 16 versus 18 years of age. This means that participants in this group more or less correspond to the 7th graders in group 3 in Rodina & Westergaard 2015, as our participants in group 4 were around 12 years old in 2014.

Table 3. Age of participants in years;months for groups 1, 2 & 3 and in years for groups 4 & 5.

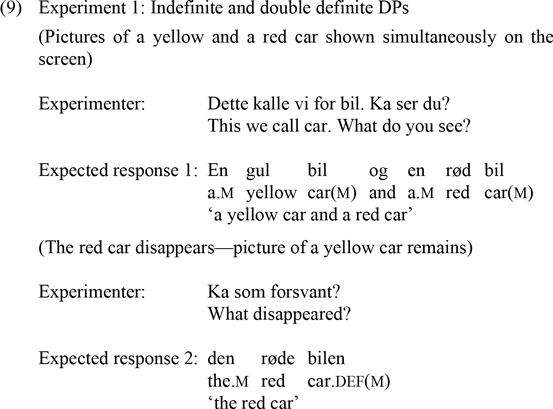

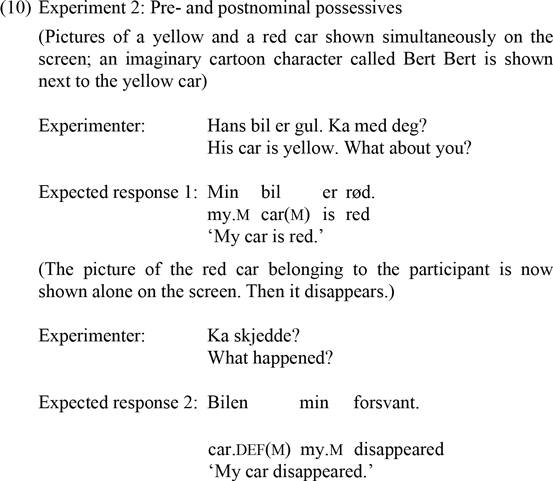

We conducted two elicited production experiments. Experiment 1 elicited indefinite and double definite forms and was nearly identical to experiment 1 in Rodina & Westergaard 2015, using the same (or similar) lexical items and the same procedure. The only difference was that the number of feminine nouns was increased from eight to twelve, and the number of masculine and neuter nouns was decreased from eight to six in the present study. The procedure is shown in 9. Experiment 2 elicited prenominal and postnominal possessives (in a contrastive and neutral context, respectively; see section 2.3), as illustrated in 10.

(9)

(10)

The lead-in statement in both tasks was carefully chosen in order not to reveal the gender of the target noun. The stimuli in both experiments consisted of the same 24 nouns: six masculine, twelve feminine (six ending in a consonant and six so-called weak feminines ending in -e, see section 2.1), and six neuter nouns. The masculine and neuter nouns were used as fillers and are not included in the analysis. The nouns were presented in a randomized order, which was also different in the two tasks. The materials were a series of colored pictures showing various objects depicting the target nouns. The pictures were presented on a laptop computer and all responses were audio-recorded. A training session using plural nouns whose agreeing forms do not show gender (for instance, blå/mine ballonger ‘blue.pl/my.pl balloons’) preceded both experiments.

The experiments were carried out by two investigators, a native speaker of Norwegian working as a research assistant and an advanced second language speaker of Norwegian (the first author of this paper). Experiment 1 was always conducted first. The experiments with the children and adolescents were conducted in daycare centers and schools, individually in a quiet room. The experiments with the adults were conducted individually at UiT The Arctic University of Norway. The adult speakers were told that the purpose of the task was to compare child and adult ability to describe objects. This was done in order to ensure that they were not conscious of the grammatical phenomenon tested.

The recordings were transcribed by two research assistants who are native speakers of Norwegian. From experiment 1, we included indefinite and suffixed definite forms. From experiment 2, we included the prenominal possessor and a combination of the suffixed definite article with a postnominal possessor. While two responses per test item were expected with indefinites, only one response was expected in all other conditions. In order to have a homogeneous sample, only the first response with indefinites was included in the analysis. All lexical substitutions, for example, andekylling ‘duckling’ instead of and ‘duck’, were excluded from the analysis. Occasionally, the target noun was missing in constructions with indefinite and double definite forms, as shown in 11.

(11)

Such responses are perfectly grammatical and were included in the counts as they do contain the relevant gender information.

4. Results

In what follows, the results are presented for the feminine nouns only.Footnote 5 A generalized linear mixed effects model analysis was performed using the lme4 and lsmeans packages in R (Bates et al. 2015). Section 4.1 compares the use of the feminine indefinite article ei and the feminine possessive mi in prenominal position. Section 4.2 presents the results for the suffixed definite forms and postnominal possessors and provides a comparison of the status of feminine nouns in the present data with the data in Rodina & Westergaard 2015.

4.1. Indefinite Articles and Prenominal Possessors

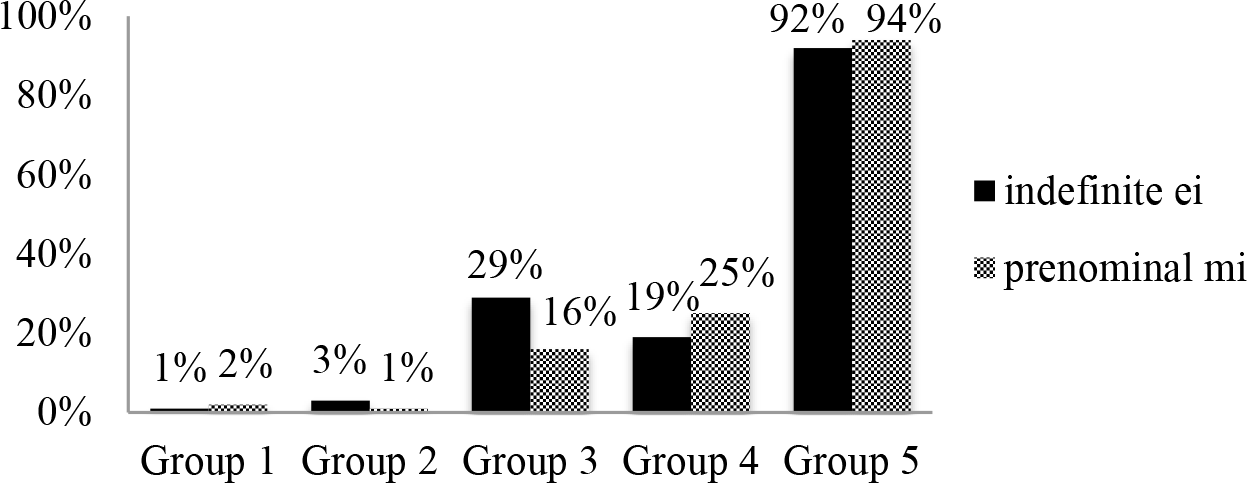

Figure 1 shows the use of feminine indefinite ei and the prenominal possessor mi across the five participant groups. The group comparison within each condition reveals that groups 1, 2, 3, and 4 use feminine ei and mi forms significantly less than group 5 (p<0.001 for all age groups with group 5 as Intercept). Furthermore, pairwise comparison of ei and mi forms within each group reveals no differences in groups 1, 2, 4, and 5 (p>0.4 for all age groups). In group 3, the use of feminine indefinite ei is found to be significantly higher than the use of prenominal mi (p=0.03).

Figure 1. The use of the indefinite article ei(f) and the prenominal possessor mi(f) with (traditionally) feminine nouns.

Table 4 presents the individual speaker preferences for indefinite articles and prenominal possessors. The majority of children and adolescents in groups 1, 2, 3, and 4 uses the masculine forms en and min exclusively (altogether 48/62 and 51/62, respectively). Nevertheless, the results for indefinite ei and prenominal mi are considerably higher in groups 3 and 4 than in groups 1 and 2. A detailed examination of the individual speaker data in group 3 reveals that four speakers are respon-sible for the use of ei (29%, 39/134) and five speakers are responsible for the use of prenominal mi (16%, 28/175). However, only two of them can be called productive users of feminine ei and mi, as only these two speakers use these feminine forms predominantly. One of them produces ei with 10 out of 12 nouns and mi with 8 out of 9 nouns.Footnote 6 The other speaker produces ei with 11 out of 11 nouns and mi with 11 out of 12 nouns. In group 4, seven participants use ei (19%, 21/113) and four participants use mi (25%, 24/96). However, only one speaker in group 4 uses the two feminine forms productively. This speaker produces ei with 12 out of 12 nouns and mi with 9 out of 10 nouns. In sum, despite the fact that the two feminine forms occur between 16% and 29% in younger speakers from groups 3 and 4, only three out of 35 speakers in these groups use them predominantly and productively.

Table 4. The indefinite articles ei(F)/en(M) and prenominal possessors mi(F)/min(M) with (traditionally) feminine nouns; N participants/Total.

Furthermore, the table also shows that in contrast to younger speakers, nearly all of the adult speakers in group 5 use feminine forms exclusively (13/15 for ei and 10/15 for mi). There is one adult speaker who uses en exclusively. The same speaker prefers to use the feminine form mi in prenominal possessives. In sum, the speakers who use the feminine and masculine forms interchangeably are a minority across all age groups. Younger speakers in groups 1, 2, 3, and 4 show a preference for en and min, while older speakers in group 5 show a preference for ei and mi.

4.2. Definite DPs and Postnominal Possessors

The use of the feminine forms of the definite suffix and postnominal possessors is illustrated in figure 2. All participant groups behave similarly in that they use the expected -a and -a mi forms between 85% and 100% of the time. The forms attributed to masculine nouns (that is, -en and -en min) occasionally occur in groups 1, 2, 3, and 4, as the definite suffix -en is used between 2% and 12% of the time by 17/62 of these younger speakers, while the postnominal -en min form is used between 2% and 15% by 12/62 speakers. A detailed analysis of the -en and -en min forms reveals that they have the same overall frequencies in younger speakers (groups 1–4). Definite -en occurs 6% (37/605) of the time in the production of 16 different speakers and -en min is used 6% (36/625) of the time by 12 different speakers. Only 8 out of 62 younger speakers use both forms interchangeably, but no one uses them productively, that is, across all or nearly all test items. Nevertheless, all 12 test nouns are used with -en and -en min forms. The highest frequency of use is found for the noun såpe ‘soap’, 20% (15/73).

Figure 2. The use of the suffixed definite article -a and postnominal possessor mi with (traditionally) feminine nouns.

The unexpected -a min form of postnominal possessives is found only three times in the data of two participants in groups 1 and 3. This is illustrated in the examples in 12. Nevertheless, these participants behave like other younger speakers of the Tromsø dialect in that they use en and min prenominally, but -a and -a mi postnominally with previously feminine nouns. The combination -en mi is unattested.

(12)

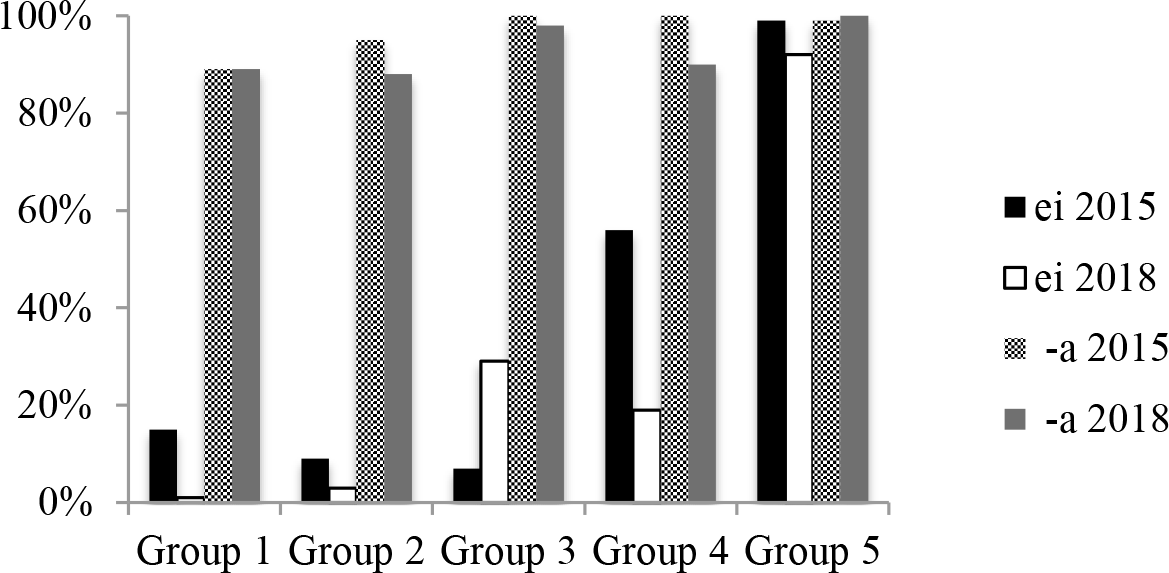

Figure 3 reflects the state of the Tromsø dialect in 2015 and at present. It compares the current data with the data on the use of indefinite ei and suffixed definite -a from the Rodina & Westergaard 2015 study.

Figure 3. The use of the indefinite article ei and suffixed definite article -a with (traditionally) feminine nouns in 2015 and 2018.

It is clear that the use of the suffixed definite article -a with feminine nouns remains intact and stable across all participant groups in both studies. The status of indefinite feminine ei is also unchanged in the adult participants. Furthermore, the child participants (groups 1–3) show a clear preference for masculine en in both studies. The major difference between the two studies appears in the data from the adolescents in group 4, where the percentage of ei reduces from 56% in Rodina & Westergaard 2015 to only 19% in the present data sample. Recall from section 3.2 that the adolescent participants in the present sample are somewhat younger than the ones in Rodina & Westergaard 2015, that is, 16 versus 18, and thus correspond more closely to the 7th graders in group 3 in Rodina & Westergaard 2015, who only produced ei 7% of the time.

5. Discussion

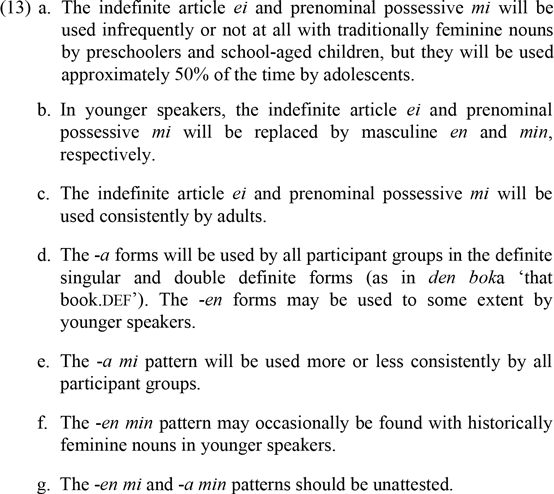

In section 3.1, we posed a number of research questions and identified seven predictions for the current study, repeated in 13 for convenience.

(13)

The results from both experiment 1 and experiment 2 confirm that there is an ongoing change in the gender system of the Tromsø dialect, since both unambiguously feminine forms, the indefinite article ei and the prenominal possessive mi, are highly infrequent in young speakers (3–16-year-olds, groups 1–4). The use of these feminine forms does not exceed 30% (see figure 1); instead, they are replaced by masculine en and min, respectively. We can thus conclude that the masculine–feminine–neuter system has been replaced by a common–neuter system in younger speakers born in 2000 and later. At the same time, the use of feminine ei and mi forms remains stable in the older speakers, aged 32–67. Thus, predictions 13a–c are borne out.

The new results for the indefinite article ei are also a close match with those reported in 2015 (see figure 3), except for group 4: The use of ei in 18-year-olds reported in 2015 was 56% and differed significantly from the use in other younger children (groups 1–3) as well as adults. In contrast, the 16-year-olds in group 4 in the present study show a similar pattern to all other younger speakers. As mentioned above, these speakers belong to the generation of speakers who were approximately age 12 in 2014, and thus correspond to group 3 in Rodina & Westergaard 2015. It is clear in figure 3 that ei continues to be a dispreferred form for these speakers in 2018. Nevertheless, there is a certain amount of individual variation among younger speakers in the present study: While none of them uses ei and prenominal mi consistently with all test items, 12 out of 62 speakers sometimes use ei/en and mi/min interchangeably (see table 4).

In contrast, the use of the suffixed definite article -a and postnominal possessive mi with traditionally feminine nouns is stable across all participant groups in the present study (see figure 2). Adults (group 5) use these forms exclusively, and children and adolescents (groups 1–4) use them predominantly. Thus, both predictions 13d and 13e are borne out, since only a small number of younger speakers (8/62) occasionally allow -en and -en min forms with previously feminine nouns. None of these speakers use these forms productively. It is not clear whether the results for suffixed definite -en are different from the findings in Oslo (see Lundquist & Vangsnes 2018), where 10 out of 33 adolescents (17–18-year-olds) used -en with the feminines consistently and three switched between -a and -en. In Trondheim, the argument for the incipient change in the declension system is mainly based on the results from preschoolers and adults who use -en 23% and 13% of the time, respectively. In the present study, -en is used by the preschoolers 11% of the time, and it is not attested at all in the adult production. In the remaining age groups, groups 2–4, the use of -en is observed 12%, 2%, and 10% of the time, respectively.

Thus, there does not seem to be sufficient evidence to argue for a change in the declension system in the Tromsø dialect. Furthermore, if there is an ongoing change in the declension system of traditionally feminine nouns, it is probably a separate development, as it clearly does not go hand in hand with the change in the gender system. Finally, the results from the postnominal possessives seem to support the contextual allomorphy account proposed by Svenonius Reference Svenonius, Gribanova and Stephanie2017. The striking discrepancy between prenominal min + N (Noun) and postnominal N-a mi forms suggests that postnominal mi is not an exponent of gender, but instead an allomorph selected under strict adjacency with the definite suffix -a. In other words, postnominal mi is used productively in the two-gender system of the Tromsø dialect, as it is conditioned by the phonology of the preceding vowel within a prosodic phrase, the definite suffix -a. The allomorphy account correctly predicts that -en mi and -a min patterns are (virtually) unattested in the two-gender system (see prediction 13g). In the new gender system, previously feminine nouns occur with masculine gender markers, as in 14a,b, but with declension suffixes of traditionally feminine nouns, as in 14c,d.

(14)

Based on the results of the present study, we conclude that speakers of the Tromsø dialect born in 2000 and later have a two-gender system consisting of common and neuter gender.

6. Summary and Conclusion

The present study has investigated the status of feminine gender in the Tromsø dialect of Norwegian. Previous research (Rodina & Westergaard 2015) has attested a change in the use of the feminine indefinite article ei, showing that it is increasingly replaced by the masculine form en in younger speakers. Based on this, it has been argued that the traditional three-gender system (masculine, feminine, neuter) is developing into a two-gender system (common and neuter). However, this could in principle be an extension of the massive syncretism that exists between feminine and masculine gender forms in Norwegian and not necessarily constitute a loss of feminine gender.

To resolve this issue, we have carried out two experiments comparing the use of the indefinite article with the only other forms that unambiguously mark feminine in the traditional three-gender system, that is, the (pre- and postnominal) possessives. The findings show that the frequency of the feminine forms of the prenominal possessive is as low as that of the indefinites in the production of children and adolescents, confirming previous claims that the Tromsø dialect is developing into a two-gender system. Furthermore, the production of the definite suffix -a with traditionally feminine nouns remains stable, as in previous research, strengthening the claim that definite suffixes are not exponents of gender, but rather declension class markers. Finally, the postnominal possessive also retains the traditionally feminine form, in sharp contrast to the prenominal possessive, supporting an account of postnominal possessives not as gender markers but as allomorphs that are conditioned by the phonological context of the immediately preceding vowel within the prosodic phrase, that is, the definite suffix -a.