Introduction

Emergency physicians have used point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) for many years and for a variety of indications.Reference Jehle, Davis and Evans 1 - Reference Schlager, Lazzareschi and Whitten 5 More recently, POCUS has been integrated into pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) practice.Reference Rosenfield, Kwan and Fischer 6 - Reference Scaife, Rollins and Barnhart 10 The technology is appealing for PEM because it is usually painless, radiation free, potentially accessible, and valuable for augmenting both clinical decision-making and therapeutic intervention.

In 2012, the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP) published a renewed position statement, supporting emergency physicians in their use of POCUS.Reference Henneberry, Hanson and Healey 11 In the same year, Kim et al. published a survey of POCUS training in Canadian emergency medicine residency programs.Reference Kim, Theoret and Liao 12 Ninety-three percent of programs included formal POCUS training at the time of the study. All of these programs were offering training in focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST), cardiac assessment, and abdominal aortic aneurysm evaluation. The majority of centres included intrauterine pregnancy and procedural guidance training.

A POCUS Policy Statement and Technical Report by the American Academy of Pediatrics was recently publishedReference Marin and Lewiss 13 supporting POCUS use and quality control in pediatric emergency departments (EDs). These documents emphasize the need for formal POCUS education during PEM fellowship training. This sentiment is shared by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, which is expected to add POCUS to the next iteration of its PEM curriculum.Reference Rosenfield, Kwan and Fischer 6

Surveys of American PEM training have demonstrated increasing inclusion of POCUS training in the last 5 years with 88% of programs reporting inclusion in 2012.Reference Marin, Zuckerbraun and Kahn 14 The current state of adoption in Canadian PEM training programs remains unknown. To our knowledge, no study has described the current state of POCUS training in Canadian PEM programs or the perspectives of both program directors (PDs) and PEM fellows regarding POCUS technology and its clinical importance.

Methods

This study consisted of two self-administered electronic mail surveys specifically designed for two subgroups of participants: Canadian PEM fellowship PDs and Canadian PEM fellows actively training. Surveys were disseminated electronically to PEM fellows of all 10 Canadian PEM fellowship programs through their PDs in 2014.

Three study investigators developed the surveys, one designed for PDs and the other for fellows. The surveys contained 20 (fellowship directors) and 21 (fellows) questions, respectively. The questions were formulated as multiple-choice response, with some exceptions (Likert scale and open questions).

To improve reliability and enhance clarity of the items, the survey was pilot tested—the PD survey by two former PDs at a single site, and the fellow survey by a group of recent PEM fellowship graduates. After refinement, the surveys were posted on a Web-based survey site (www.surveymonkey.com). The PDs of all 10 Canadian PEM fellowship programs were approached in person in January 2014 by one of the co-authors (BC). From April 2014 until October 2014, a modified Dillman’s Tailored Design Method was used to enhance response. We sent repeated emails to the PDs, explaining the study, asking them to respond to the director’s survey and to pass the link of the fellow’s survey to their fellows. All participants were ensured of confidentiality and were provided instructions for survey completion. Data were collected electronically and analysed in an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Richmond, WA). For analysis, we calculated proportions for each outcome.

The primary outcomes were the proportion of PEM programs that offers a formal curriculum in ultrasound (PD survey) and the training received by fellows during their fellowship (fellow survey). Secondary outcomes were 1) to describe current training in POCUS in PEM fellowship programs, 2) to compare what kind of training that PEM programs offer with what fellows actually receive, and 3) a needs assessment by fellows and PDs for the content of future training programs in POCUS.

The protocol was accepted by the Institutional Review Board of the CHU Sainte-Justine Research Institute. Informed consent was implied for participants who agreed to respond to the survey.

Results

A total of 9/10 (90%) of PDs and 42/60 (70%) of PEM fellows responded to the survey. The responses represented all Canadian PEM training centres, except one.

Twenty-nine out of 41 (70%) of the PEM fellows reported having no POCUS training prior to their fellowship and 28/38 (74%) had POCUS training during fellowship. Among them, 13/38 (33%) reported pediatric-specific POCUS training. A formal curriculum in POCUS was established in 5/9 (56%) PEM programs as per the PDs, but only three programs offered PEM-specific training. All five programs established their training programs in 2011 or 2012. The applications included in the training programs varied between centres. The FAST and focused cardiac assessment were the most frequently taught (Table 1).

Table 1 POCUS training during PEM fellowship

Twenty out of 40 (50%) fellows reported that their peer fellows use POCUS at least once a week, and 4/9 (44%) PDs reported the same; 7/9 (78%) of PDs and 20/40 (50%) of fellows stated that the majority of faculty rarely or never uses POCUS in clinical practice. But, only 11/39 (28%) of fellows and 4/9 (44%) of PDs stated that fellows rarely or never use it.

The FAST examination was the most commonly used clinical application (44% of the PDs and 64% of the fellows responded that it is used most of the time or always). Other indications were rarely applied for POCUS use: only three fellows responded that it is used most of the time for cardiac, pulmonary, and musculoskeletal assessment, and one PD reported that POCUS was mostly used for pulmonary and abdominal assessment.

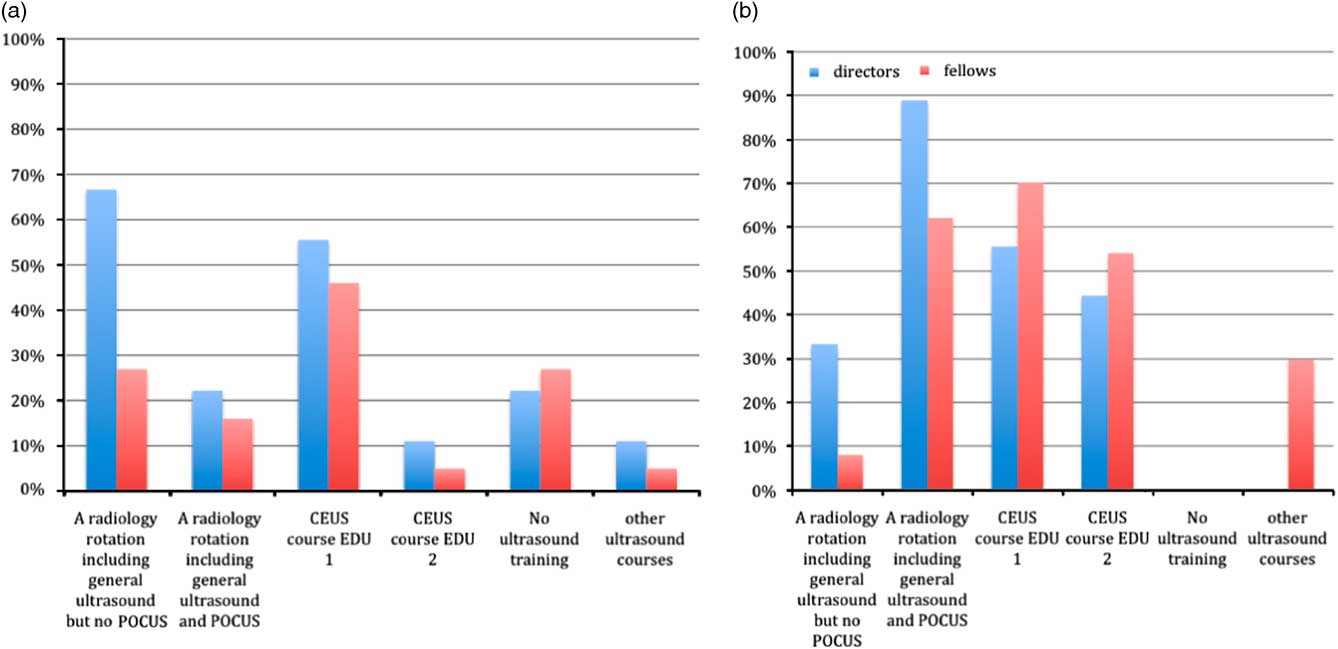

Eighty-six percent of fellows and 80% of PDs stated that training in POCUS was very important or essential for PEM training. Both fellows and PDs responded in favor of incorporating formal POCUS training into their PEM program (Figure 1). However, fellows ranked POCUS to be comparatively more important than other core curriculum elements when contrasted with PD responses. We asked them to compare the relative importance of different procedural interventions during their fellowship: POCUS, resuscitation, trauma, orthopedic techniques (e.g., fracture reduction), and sedation/nerve blocks, using a Likert scale of 1 (“not important”) to 5 (“very important”). No PD reported the actual importance of POCUS as 5, and one stated that POCUS should have an importance of 5. When asking fellows the same question, results were different: 19% reported the actual importance as 5, and 46% stated that POCUS should have that maximal state of importance. These results were comparable to the importance given to procedural sedation and nerve blocks as far as fellows were concerned (49% gave it a 5 on the Likert scale for the importance it should have), whereas PDs rated sedation higher than POCUS (44%). Fellows as well as PDs rated resuscitation, trauma, and techniques more important than POCUS during fellowship training: fellows gave it a 5 on the Likert scale in 89%, 86%, and 62%, respectively, and for PDs the numbers were 89%, 89%, and 67%.

Figure 1 The following training in Medical Imaging a) is part of our program and b) should be part of the program in the future (other: ECCU or equivalent, pediatric specific Canadian Society of Emergency Ultrasound (CEUS) course, specific pediatric POCUS course, video quiz, module-based programming).

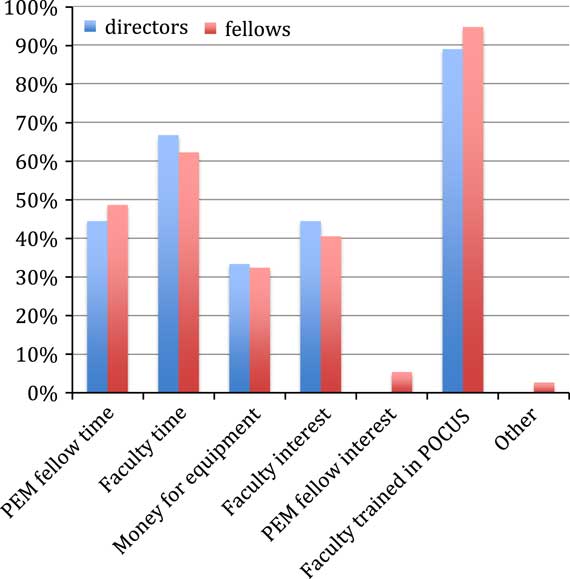

Fellows and PDs stated that the major barriers to training were lack of trained faculty (95% and 90%, respectively), followed by insufficient faculty time (62% and 67%), fellows’ time (49% and 44%), and faculty interest in the technology (41% and 44%) (Figure 2). PDs of all nine programs reported access to an ultrasound machine in their ED. Seven ED settings owned their own ultrasound system, and one was planning to buy a system imminently.

Figure 2 “Important barriers in learning POCUS during my PEM fellowship is that there is not enough. . .”

Discussion

POCUS has become an important adjunct in the pediatric ED and is gaining more and more importance in PEM practice and fellowship training.Reference Gallagher and Levy 8 , Reference Henneberry, Hanson and Healey 11 , Reference Marin, Zuckerbraun and Kahn 14 However, the integration of POCUS in Canada still lags behind the U.S. PEM fellowship programs. Ramirez et al. (2006) and Marin et al. (2011) queried all U.S. PEM fellowship directors with surveys concerning this subject, and, in 2008, Chamberlain et al. sent a survey to all U.S. pediatric emergency medical directors, fellowship directors, and graduating fellows.Reference Marin, Zuckerbraun and Kahn 14 - Reference Chamberlain, Reid and Madhok 16 In 2011, 53/60 (88%) of U.S. PEM programs responding to their survey offer some POCUS training to their fellows,Reference Marin, Zuckerbraun and Kahn 14 compared to 65% in 2006Reference Ramirez-Schrempp, Dorfman, Tien and Liteplo 15 and 56% of the Canadian programs in our study. A pediatric-specific POCUS curriculum is currently offered in only three (33%) of the Canadian PEM programs, which is similar to U.S. reporting 5 years ago.Reference Ramirez-Schrempp, Dorfman, Tien and Liteplo 15

Marin et al.Reference Marin, Zuckerbraun and Kahn 14 reported 63% use of FAST (“most of the time” or “always”) in U.S. hospitals with a pediatric EM training program, compared to 50% in our study. In the study by Chamberlain et al., FAST use was reported by fellows to be 93%.Reference Chamberlain, Reid and Madhok 16 In that same survey, 53% of responders (fellows, PDs, and medical directors) stated that POCUS was used for soft tissue evaluation in their ED, 37% stated its use for cardiac assessment, 9% for abdominal assessment, and 40% for procedural guidance. In our study, the vast majority of PEM fellows stated that POCUS was used for these indications “never,” “rarely”, or “sometimes” (36 fellows for musculoskeletal problems, 35 for cardiac, 39 for abdominal assessment, and 36 for procedural guidance).

Fellows in our study were more enthusiastic about use of POCUS in their EDs than their PDs. A potential explanation for this difference might be that PDs underestimate the use of POCUS, whereas fellows have broader insight to daily practice because they work directly with a great number of staff. The fellows’ presence might also stimulate staff to use POCUS more often.

Fellows in general believed POCUS to be more important than their PDs. This difference could be explained by a number of factors, including the fellows’ clinical experience with the technology, their understanding of the literature, their comfort with technology, or the sophistication and growth of their clinical practice. One of the PDs commented: “I am not convinced that POCUS, despite it being sexy and fun, has really been shown to improve patient care in a pediatric setting.” Although this might represent a familiar sentiment, the body of literature to support the use of POCUS in PEM is becoming more and more robust and includes literature that supports the use of POCUS for assessment of heart and lung pathologies, intussusception, hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, appendicitis, long bone fractures, skull fractures, skin and soft tissue infection, and procedural guidance.Reference Chen and Baker 7 - Reference Levy and Bachur 9 , Reference Leeson and Leeson 17

The majority of fellows stated that they would like to incorporate a CEUS course (70% for emergency department echography [EDE] 1, 54% for EDE 2) as part of their POCUS curriculum, whereas 30% asked for “other” courses (the latter included pediatric POCUS courses). This response suggests that the majority of sites still lack the capacity to incorporate POCUS into their curriculum due to a lack of local expertise or instructional infrastructure and are dependent on third-party training. However, PEM POCUS fellowship programs that are developing leaders in PEM POCUS may soon remedy this issue.Reference Rosenfield, Kwan and Fischer 6

The fact that FAST examination is the indication most commonly used and taught is not surprising. The FAST examination is part of the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) program and one of the original POCUS indications. However, its use and impact in the pediatric setting is still unclear and has been shown to be less helpful than in adult counterparts.Reference Scaife, Rollins and Barnhart 10 Curricular development should include specific pediatric considerations rather than “adopting” adult training.

Some of the barriers identified in our study are of temporary nature, and integration of POCUS training in Canada PEM fellowships should mirror the impressive adoption seen in U.S. programs in the near term.Reference Marin, Zuckerbraun and Kahn 14 For example, the use of external resources can negate the current lack of trained faculty and bridge programs until local faculty is adequately trained to supervise fellows. Both CCFP-EM and FRCPC have traditionally relied on EDE programs for all POCUS training, but they slowly are transitioning to more site-specific content as a result of more fellowship-trained POCUS faculty (e.g., University of Toronto). Similarly, the perception that POCUS impedes workflow may reflect a lack of faculty experience and the lack of infrastructure that promotes timely and accessible use of POCUS. More challenging is the lack of time available in many curriculums for POCUS training. Only with greater recognition and supporting evidence can POCUS be expected to replace other elements of training.

Both PEM fellows and PDs agree that POCUS is very important or essential for PEM training. This suggests that the majority of fellowship programs would welcome a PEM-specific curriculum, as well as materials for training and tools for assessing competency.

Limitations

The major limitation of this study is the small sample size. However, we did receive responses from a high proportion of possible respondents. Another limitation was that PDs had to pass the survey to their fellows. We chose this way of communication due to that there is no database to allow us to access fellows directly recognizing that it could lead to bias. Also, responders were likely more interested in the subject than those who did not answer. Similarly, some sites had several fellows responding, whereas others had very few, making it difficult to interpret the result as being representative of all Canadian PEM fellows. Still, the response rate of 9 of 10 PDs and 70% of actual training fellows suggests a reasonable description. Finally, we wanted to keep the results anonymous, and, because some programs are very small, we were not able to differentiate fellows per site and remove regional bias.

Conclusion

PEM fellows and PDs agree on the importance of POCUS in PEM and the need to reprioritize this training. There is a wide variation in the execution and content of the training that does exist, with only 56% of Canadian PEM fellowship programs offering integrated POCUS training as part of their curriculum. The greatest barrier appears to be a lack of trained faculty to teach. The opportunity exists to develop a standardized curriculum as well as to augment faculty-training capacity across Canada.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank all participants of this survey.

Competing interests: None declared.