No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 March 2004

On April 27, 2002, while walking in the garden of his home in Cambridge, one of the premier American archaeologists of the twentieth century was taken from us suddenly, by massive heart failure, at the age of 89. Gordon R. Willey was appointed the first Charles P. Bowditch Professor of Central American and Mexican Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University in 1950 at the tender age of 37, without ever having set foot in Mesoamerica. In later years Willey happily introduced himself to people as a “Maya archaeologist,” but his importance transcends his long and distinguished career in that area.

On April 27, 2002, while walking in the garden of his home in Cambridge, one of the premier American archaeologists of the twentieth century was taken from us suddenly, by massive heart failure, at the age of 89. Gordon R. Willey was appointed the first Charles P. Bowditch Professor of Central American and Mexican Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University in 1950 at the tender age of 37, without ever having set foot in Mesoamerica. In later years Willey happily introduced himself to people as a “Maya archaeologist,” but his importance transcends his long and distinguished career in that area.

In the early part of his life Willey made vital contributions to the archaeology of North, South, and Central America, but he is most renowned as the creator of the field of “settlement pattern studies.” This new “settlement pattern” approach was a tremendous theoretical and methodological advance, one that Willey pioneered during a single season in 1946, while working in the Viru Valley of Peru. Willey was able to show that the way in which people distributed their dwellings and towns across the landscape provided an important window onto the organization and evolution of past societies. This approach was so revolutionary and productive that Willey was selected for the new post that opened at Harvard, chosen ahead of all of Alfred M. Tozzer's former students, at a time when Tozzer was the “dean” of Maya archaeology.

In 1953 Willey took Tozzer's advice and moved his research arena from Lower Central America north to the Maya area. In the following three decades he earned an impeccable reputation for his innovative and superbly documented research at numerous Maya archaeological sites in Belize (then British Honduras), Guatemala, and Honduras.

As a youth, Willey was both a sprinter and a writer who displayed a marvelous facility with the English language. Born in Chariton, Iowa, on March 7, 1913, the only child of Frank and Agnes (Wilson) Willey (a pharmacist and a teacher), he and his parents moved to southern California when Willey was 12 years old. While in Long Beach he shone in academics and in track. After reading William H. Prescott's Conquest of Mexico and Conquest of Peru, he decided to study archaeology. His Latin American history teacher at Woodrow Wilson High School persuaded him to study under Byron Cummings, a renowned field archaeologist and teacher of Southwest U.S. archaeology. Cummings was a revered faculty member at the University of Arizona, where he was not only the Dean of the Faculty of Sciences, Arts, and Letters but also an athletic booster. In his memoirs (Portraits in American Archaeology: Remembrances of Some Distinguished Americanists, 1988), Willey wrote that, at their first meeting, Cummings seemed a bit disappointed at the youthfulness and slimness of his new charge. But as a devotee of track, Cummings was quickly won over when Willey showed his speed by setting several school records, including those for the 60- and 220-yard dash. Decades later, Willey loved to tell new acquaintances that he still held the record for the 60-yard dash at the University of Arizona. After a suitable pause, he would let on, deadpan, that “o'course, they don't run that one anymore.”

Besides being fast on the athletic track, Willey was a quick study in the academic arena. Although he dreamed of doing archaeology in Egypt or the Near East, Cummings led Willey back to American archaeology, and Cummings' courses on Mexico were the ones that Willey said he enjoyed most during his years at Arizona. “The Dean,” as Cummings was known, took the young Willey on field expeditions in the Southwest and to dig at the site of Kinishba in Arizona (Figure 1). Willey's interests in archaeological chronology were fueled by courses he took in dendrochronology from Charles Fairbanks. After completing his B.A. in Anthropology in 1935, he continued on at Arizona, obtaining his M.A. the following year with a thesis on “Methods and Problems in Archaeological Excavation, with Special Reference to the Southwestern United States.” During this year in graduate school, Willey earned extra money by serving as the freshman track coach at Arizona. Given his later prominence, it is ironic that Willey was denied admittance to the leading doctoral programs in archaeology (including Chicago and Harvard) after obtaining his degrees at the University of Arizona. By reading between the lines in Willey's memoir, it is clear that Cummings was impressed with his student's abilities and his intellectual “reach” and secured for him a Laboratory of Anthropology Summer Field Fellowship with Arthur R. Kelly, in Macon, Georgia. With his Master's diploma in hand, Willey eagerly departed for this new challenge in June 1936.

Willey (in dark shirt, second from right) at the University of Arizona'a Archaeological Field School in Kinishba, 1935). (Courtesy Peabody Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.)

That first summer in Georgia, Willey labored at the Stubbs Mound, getting “up to speed” very quickly on Southeast archaeology. This entailed learning about the sites in the region, their ceramics, chronology, and other aspects of material culture. With Kelly's active support, Willey's first publication (in 1937) was an initial stab at a dendrochronology sequence for the Southeast. This was not only a reflection of his work with Fairbanks at Arizona, but also the harbinger of a career devoted to the mastery of what he loved to call “space-time systematics.” With “his first boss in archaeology,” Willey carefully observed the finer points of running a major excavation. He admired the “military” bearing that Kelly had with the hundreds of work hands, staff, and students on his Works Progress Administration excavation project, and came to realize the drawbacks of running such a large operation. He perceived that Kelly's role as a public spokesman and advocate for the field delayed his writing it all up. This was an issue that Willey broached in his memoir on Cummings as well, saying that, for all his first mentor's greatness as a teacher and citizen of the university, he never adequately published the results of all his archaeological fieldwork. These were lessons that Willey learned well, and in coming years he earned a stellar reputation for sprinting into print with the results of his most recently completed fieldwork. As his long-time close friend and colleague Evon Vogt put it, “Gordon was always known in the trade for having one monograph just out, another one in press, and another one he was working on.”

Willey's first monograph, Crooks Site: A Marksville Period Burial Mound in LaSalle Parish, Louisiana, published in 1940, was but one product of his collaboration with James Ford. Ford and Willey had become close friends in Macon, finding much to discuss (and in Ford's case, but not Willey's, much to argue about) with regard to chronology, ceramics, and archaeology in general. It was with Ford that Willey immersed himself in the study of ceramics and the insights that they could provide on “the big picture” of cultural change and exchange through time and through space.

In Macon Willey also had been blessed to meet, court, and wed Katharine Winston Whaley. Katharine was to be Gordon's life-long muse and closest friend, through 63 years of happy marriage. After their wedding in September 1938, they moved to New Orleans to work on Jim Ford's Federal Relief Project. Ford was the only colleague in Willey's Portraits volume whom Willey ventured could be considered a genius in archaeology. Clearly, from the beginning, Ford and Willey respected each other immensely. Their brainstorming on ceramic sequences throughout the region would lead to an innovative article, “An Interpretation of the Prehistory of the Eastern United States,” published in 1941 in American Antiquity. Years later, Willey would recount the story of his changing, at the last minute, the first words of the title, from “A Key to the” to the unassuming “An.” This modesty and careful choice of words was characteristic of Willey's writing throughout his career and was much appreciated by his readers. But at the time, Ford was absolutely furious!

All of Dean Cummings' letter writing and Willey's hard work with Jim Ford paid off when Gordon was admitted to the doctoral program in anthropology at Columbia University. Upon Willey's September 1939 arrival in New York, his new teacher William Duncan Strong immediately invited him to a meeting with the renowned scholars George Vaillant and Harry Shapiro. During his time in graduate school Willey became a great admirer of Strong for his skill as a seminar and classroom teacher and for the support he provided for his students' research. He was especially moved by the way that Strong arranged for his graduate students to meet, formally and informally, with the great figures in their field to discuss the burning issues of the day. It was a practice that Willey would emulate, with great success, when he embarked on his own teaching career at Harvard.

In 1940, while a graduate student at Columbia, Willey dug in Florida and immensely enjoyed his work there. He was amazed and grateful when Matthew Stirling, Director of the Bureau of American Ethnology, offered him all the materials and notes from his own extensive Gulf Coast digs from the Federal Relief Agency project he had directed in the previous decade. With the self-effacement that was his trademark, Willey opened his 1949 book on the Archaeology of the Florida Gulf Coast with the caveat that no one should consider the work to be “the last word on the subject.” Nevertheless, it has held up remarkably well through half a century of subsequent archaeological research in the region. When the monograph was re-issued in 1998, Willey noted that not all his Florida colleagues looked kindly upon his work when the book first came out. He reported that one prominent archaeologist had scoffed that it “set Florida archaeology back 50 years.” Yet 50 years later, it was still so valuable that the Florida State Museum re-published it, with the museum's publication series editor, Jerry Milanich, proclaiming in the preface that not only was the book a venerable one but also “Gordon Willey himself is a classic.” Willey fully intended to write his dissertation on Florida archaeology and eventually did publish the Gulf Coast book and another monograph on his own Excavations in Southeast Florida (Yale University Press) in 1949. But fate took him in a different direction.

In 1941 he shifted his geographic focus from the Southeastern United States to South America, when, accompanied by Katharine, he took his first sojourn to Latin America. Strong had arranged for himself and Willey to conduct excavations at the coastal sites of Ancon and Supe and then at the famed Inca oracle site of Pachacamac. From September 1941 to March 1942, Willey and James Corbett excavated at Chancay, Puerto de Supe, and Ancon. Always a quick study, Willey rapidly absorbed the ceramic sequences he was exposed to in Peru, and sprinted to the finish line once more. The Chancay materials formed the basis of Willey's dissertation, completed during his third and final year in the Ph.D. program and published the following year. Willey and Corbett together subsequently published the monograph, Early Ancon and Early Supe Culture: Chavin Horizon Sites on the Central Peruvian Coast (1954).

Upon completing his Ph.D. in 1942, Willey served for a year as an instructor in anthropology at Columbia. With the backing of Strong and Stirling, he secured a post at the Bureau of American Ethnology at the Smithsonian the following year (Figure 2). There he spent several years working on the monumental Handbook of South American Indians, with the distinguished social anthropologist Julian Steward who was to have a profound effect on the young archaeologist. Willey wrote many articles for the Handbook on archaeology and ethnology and coaxed work out of other authors while keeping the manuscripts flowing. As editor, Steward was “a great worrier,” yet Willey's memoir of him is full of admiration and marvelous anecdotes of their time together. Importantly, it was Steward who suggested that Willey not merely do a series of test pits for dating and building up a cultural chronology, but also pursue a more original and valuable approach in the upcoming project in Peru's Viru Valley: “Why didn't I, instead, concentrate on overall settlement patterns, with particular reference to when and how these patterns changed through time and what the changes implied?” The Viru project was a somewhat complicated endeavor, involving archaeologists from Columbia, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Smithsonian (Figure 3). Willey later wrote that he occasionally felt envious that his colleagues were digging test pits, unearthing architecture, and putting together a regional cultural sequence, while he was out surveying the landscape and experimenting with an unorthodox new method for reconstructing the past.

Willey's Smithsonian identification card, 1943. (Courtesy Peabody Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.)

Doing archaeological survey in the Viru Valley, Peru, 1946. (Courtesy Peabody Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.)

When settlement pattern archaeology became the “leading edge” of American archaeology in later years, Willey modestly attributed its success to Steward's ideas and to Ford's relentless energy in finding, recording, and gathering pottery from the surface of hundreds of sites they surveyed together in Viru. With characteristic candor, Willey freely admitted he was never one for “roughing it” in the field. By contrast, Ford most certainly was and was clearly disappointed that Willey didn't share this desire to “test himself.” In his memoir, Willey recalled that Ford pushed his mind and his body to the limit in the Southeastern United States and later in Viru. During their surveys in Viru, Ford once complained to his friend, “Gordon, the trouble with you is, you don't like to punish your body.” Gordon was too polite to say what he was thinking, namely “Jim, old boy, you've never spoken a truer word.” Instead, Willey focused on the race to get the material processed, analyzed, and published. He occasionally remarked that there were two kinds of archaeologists, those that enjoyed the camping and digging parts and those that preferred to write the stuff up. He was proud to include himself among the latter.

However, it is clear that Willey relished his ocean voyages, whether they were to Peru or, later on, to Panama, Mesoamerica, or England, where he was a Visiting Lecturer (in 1962–1963) and an Overseas Fellow (in 1968–1969) at Churchill College, Cambridge University. This joy was very much in keeping with the way he seemed to be able to “navigate” in virtually any archaeological sea in which he set sail. There are some rather remarkable similarities between Gordon Willey and the nineteenth-century navigator Nathaniel Bowditch, whose grandson was to endow the Harvard Chair that Willey would be the first to hold. Born into modest means, young Bowditch distinguished himself early on with his keen analytical mind, which he applied quickly to mathematics and eventually to navigation. The interest in the “big picture” was clearly there as well, in Bowditch's case resulting in superb navigational charts that covered the globe and were spectacularly popular among ship captains because of their accuracy and reliability. Eventually honored by Harvard with an honorary degree, Bowditch's modesty and humble background almost prevented him from attending the ceremony. These character traits were not the only things the two shared. In his office in Room 37 of the Peabody Museum, Willey looked across the room at two large maps: North and Central America on the left; South America on the right. Big picture, indeed. Bowditch's grandson, Charles Pickering Bowditch, was also mathematically inclined, but selected Maya archaeology as his field of inquiry. In 1910 C. P. Bowditch published a superb book, The Numeration, Calendar Systems and Astronomical Knowledge of the Mayas. (Remarkably enough, he noted a recurring pattern of dates at Piedras Negras, Guatemala, and correctly deduced that there was significant historical content in the Classic Maya inscriptions, but no one was to take up his lead until Tatiana Proskouriakoff did so at the Peabody Museum in the late 1950s.)

The dig that Willey was later to recall as his favorite intellectual voyage came about as a result of his association and friendship with Stirling. While still at the Smithsonian's Bureau of American Ethnology, Willey enjoyed numerous lunch conversations with Stirling. In one of their many wide-ranging discussions, they agreed on the need to address “the very general problem of Mesoamerican–Peruvian relationships” through new archaeological excavations. They elected to “leap right out into the middle. In other words, why not Panama?” In 1948, Stirling, the Director of the Smithsonian's Bureau of American Ethnology, asked his younger colleague if he wanted to go, and Willey assented immediately. This research was to result in the filling in of the entire pre-Columbian ceramic sequence for Central Panama and most notably the discovery of its earliest complex, Monagrillo (2500–1000 b.c.). Willey often said that the dig in the Monagrillo shell mound was his favorite archaeological excavation. “I really felt like I had a handle on it all,” he would proudly say.

In the winter of 1949, Willey was ushered into the study of the great doyen of Maya archaeology, Alfred Tozzer, at his home on 7 Bryant Street in Cambridge by their mutual friend, Philip Phillips. After some potent martinis, Tozzer asked Willey what he would do if he were to be appointed the Bowditch Professor at Harvard. Willey quickly and confidently replied that he would continue his research in Panama and dig his way north to the Maya area. In this way, he recalled telling Tozzer, he would “eventually attack the mysteries of the Maya from this southern or Lower Central American side, and by doing so we would come to know more about this ancient civilization by appreciating it in a more comprehensive setting.” Despite this admirable framing of the Maya world in a larger context, Willey faced an uphill battle. In the search for a Mesoamericanist successor to Tozzer, Willey was like a lone captain in several key respects. He had never worked in Mesoamerica, had never gone to Harvard (despite his early efforts to do so), and had never studied under Tozzer. He was also, in the context of those times, not of the right social station to “fit in.” Fortunately, in their first meeting Tozzer let Willey know that he was not among those who believed that “virtue resided only with the wealthy.” He supported Willey's candidacy for the newly created post, which sailed through on the strength of Willey's productivity, broad knowledge, and innovative ideas. To Willey's amazement, when the president of Harvard interviewed him, he politely inquired “Tell me, Willey, will you be requiring a salary?” (Fortunately, they did not ask me the same question!)

Willey's memoir is full of lively anecdotes of his first years at Harvard's Peabody Museum, where his office was right across the hall from Tozzer's. One day when Tozzer came by to visit, he discovered that Willey had acquired a shiny new metal desk and chair for his office (Tozzer had neither). Willey reported that Tozzer was distraught to learn that Bowditch funds had been used for the purchase. After berating his young colleague, saying that there were plenty of chairs in his attic, Tozzer's sense of humor got the better of him. Striding back into the room, he said mischievously, “You know, Gordon, when you were appointed to the ‘Bowditch Chair,’ that was something you should have taken figuratively, not literally. It didn't mean you were going to be given a ‘chair’! You were supposed to have your own ‘chair’!”

With the force of his personality and collegial manner, Willey quickly earned the respect of his colleagues in the Department of Anthropology at Harvard. Within 3 years of his arrival, he was selected as the department chair. This was a task that he clearly disliked, complaining about its rigors to several colleagues, including his intellectual hero, Alfred Kroeber. “Stick to your archaeology,” was the advice Kroeber gave him. Willey was only too glad to oblige and, after his 3-year stint, never took up another administrative post at Harvard. Willey was far too engaged in his research to trifle with administrative matters, preferring to let others shoulder the load. The sole exception was his distinguished service as the Chair of the Board of Senior Fellows in Pre-Columbian Studies at Dumbarton Oaks, Harvard's research affiliate in Washington, D.C., from 1973 to 1986, and as Senior Consultant to that program from 1980 to 1983. Willey's was a research appointment with the Peabody Museum, rather than a teaching post in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, allowing him to devote each spring semester exclusively to his research.

Years after his retirement he once confided to me that he detested academic politics and had done everything possible to avoid them during his entire career at Harvard. He made no attempt to avoid Tozzer, however. Tozzer was fond of giving his successor the benefit of his considerable wisdom and long experience at Harvard, and Willey was grateful for his guidance. Tozzer had been a consummate citizen of the university, serving so well in various important administrative capacities that he was given the ultimate honorific title, and always referred to as Mr. Tozzer. Although not a spellbinding lecturer, Tozzer was revered by his students and clearly excelled in his role as a teacher. Willey wrote that Tozzer always gave him good advice and that Willey always took it. One particularly important bit of counsel was when Tozzer insisted that Gordon needed to stop working in Panama (where he had returned in 1952, in his first foray into the field as Bowditch Professor) and move right away into the Maya area. This Maya work, he exclaimed with some exasperation, was the wish of C. P. Bowditch who had bequeathed a large sum to Harvard for the professorship that bore his name. Willey took Tozzer's advice and said he was glad that he did: “Certainly, if I had continued with my original plan, I think retirement would have overtaken me about halfway through Costa Rica, on my mole-like progress toward the Maya frontier. I conceded and leapt into the Maya area directly.”

In 1953 Willey began his field research in the Maya area in British Honduras. He had sought the counsel of his Mayanist colleague at the University Museum of Pennsylvania, Linton Satterthwaite, as to where a good zone to study ancient Maya settlement patterns might be. Satterthwaite invited Willey to meet him in the field, where he could show him some promising locales in the Belize River Valley before departing for his own dig at the major site of Caracol. After several days of rugged survey cutting brechas through the thick bush, during which Satterthwaite, and Willey's graduate student Bill Bullard, displayed significantly greater talent in wielding a machete than he did, they took a breather at a local watering hole. There two local gents told them about an area right along the banks of the river that had recently been cleared. Satterthwaite objected that it was located in a marginal area, away from any major centers, and chosen simply because Willey “didn't like cutting brechas! You want it already cleared off for you!” Willey calmly “admitted as to how that had certain advantages” and rapidly set to work on a project that was to change the course of Maya archaeology forever.

The Belize Valley settlement patterns project was the first archaeological program to be supported by the National Science Foundation, and the program left its mark on Maya archaeology in a way that very few projects in that part of the New World have, before or since. Although Oliver Ricketson had earlier surveyed the settlements north and south of Uaxactun, and Eric Thompson and Robert Wauchope had studied Maya housemounds and houses of various sizes, Willey was the first to bring the study of settlements to the forefront of Maya research. Once again, he was quick to deliver. The settlement pattern focus in the Belize Valley proved extremely productive, showing that there were densely occupied areas at considerable distances from the major centers, and leading to examinations of the structure of ancient Maya society. The excavations of the humbler households showed that much of what was considered to be “elite” culture (including elaborately painted polychrome ceramics) was in fact shared by commoners. The ceramics also enabled Willey and his graduate students to tie the households to larger currents of economic exchange and culture change (Figure 4).

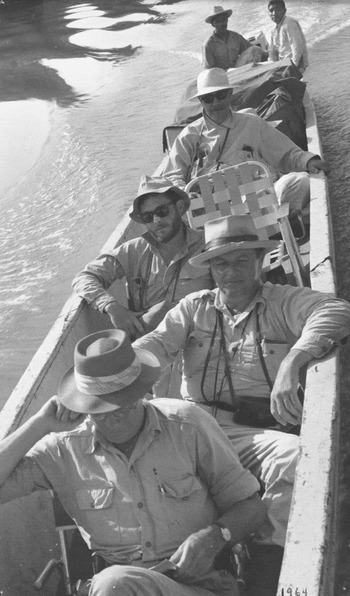

Willey and his students on a dig in the Belize River Valley, 1954. (Courtesy Peabody Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.)

In the same year that he began his work in Belize (1953), the highly regarded Prehistoric Settlement Patterns in the Virú Valley was published by the Smithsonian. The following year, his monographs The Monagrillo Culture of Panama (co-authored with Charles McGimsey and published in the Peabody Museum Papers series) and Early Ancon and Early Supe (with John Corbett) appeared. In 1955 his broader, comparative interests shone in an American Anthropologist article, “The Prehistoric Civilizations of Nuclear America.” His friend and colleague Phil Phillips collaborated with him on a major assessment of “Method and Theory in American Archaeology,” first published in the American Anthropologist, in two installments in 1953 and 1956. These seminal articles were later expanded into a book of the same name and published in 1958. These were the source for the famous (and still widely cited and discussed) dictum that “American Archaeology is Anthropology or it is nothing.” As Richard Leventhal has shown, Willey and Phillips' stand in looking at the cultural “development” of American aboriginal peoples was unusual for those times. The term evolution was often equated with Marxist thought at a time when McCarthyism was at its height. Their discussions of “stages” in that “development” never made use of the word evolution, but nonetheless helped propel evolutionary issues to the forefront of discussions in American archaeology.

These diverse research interests, and Willey's willingness to take on the big issues of the day, propelled him into the forefront of American archaeology. In 1961, he was elected president of the American Anthropological Association. Willey's presidential address, “The Early Great Art Styles and the Rise of the Pre-Columbian Civilizations” (published in 1962 in American Anthropologist), doubtless came as a bit of a surprise to many of his colleagues in the field of American archaeology. It was not a topic that he had addressed in his own research, which had been focused on ceramics, space–time systematics on the local and regional scales, settlement patterns, and social structure. Yet Willey was always quick to spot new goals on the horizon, and clearly his vision had been broadened by his research on the “high cultures” of Peru and then of Mesoamerica. Although the search for causality in the ideological realm was an innovative and visionary attempt at plotting a new course, the rest of the profession clearly wasn't ready for it. Unlike the change in tack that Willey successfully led with settlement patterns, his colleagues did not follow this particular lead. Willey himself was not to publish again on the subject until his 1973 article, “The Content and Integrity of the Mesoamerican Ideological System” in The Iconography of Middle American Sculpture. Ideology's role in culture change was a direction whose time had not yet come in American archaeology as practiced in 1961.

Instead, the 1960s saw the full flowering of the “new archaeology,” which decried the traditional pursuit of culture history that Willey had so completely mastered. The new goal was to not merely describe, but to explain, culture change, grounded in a positivist approach. This paradigm shift was deemed to require a complete overhaul of traditional methods, and the controlled use of anthropological models that would be tested with a hypothetical and deductive methodology, paying acute attention to sampling and probability theory, and a greater focus than ever before on the interaction of human populations with the natural environment. Willey was fully abreast of the new developments and saw much in them for the betterment of the profession. But unlike other colleagues he did not try to “re-invent” himself or the methods and perspectives that had served him and his chosen field so well over the years. Willey's determination to “stay the course” was greatly admired by many of his contemporaries. He was their captain, having steered them through the rocky waters occasioned by Walter Taylor's and Clyde Kluckhohn's earlier critiques of the field, with his American Antiquity articles and his book, Method and Theory in American Archaeology. But his conservatism was not so well received by the younger generation. Nevertheless, culture history has endured, and students continue to find Willey's massive summaries of New World archaeology, An Introduction to American Archaeology, Volume I: North and Middle America (1966) and An Introduction to American Archaeology, Volume II: South America (1971) very useful.

Willey's skills at assimilating and synthesizing ideas and data on American archaeology became the stuff of legend after his compilation of the prehistory of the entire Western hemisphere in the Introduction. Those two volumes were feats of data synthesis that had never been accomplished and likely will never be attempted by a single author again. The same mastery was displayed in his work as editor of two volumes on archaeology in the Handbook of Middle American Indians (1965). Likewise his volume on Courses Toward Urban Life (co-edited with the great Robert Braidwood) showed his interest in formulating answers to the big questions in archaeology, beyond the shores of the Americas. With marvelous prose, he seamlessly incorporated what most thought to be blatantly contradictory perspectives in a single coherent treatment that proponents of both sides could accept. He was especially noted for bridging the gap between the materialist and ideationist perspectives toward explanation in archaeology, as best put forth in his article, “Toward an Holistic View of Ancient Maya Civilization” (1980; published in Man). One of my favorite archaeological anecdotes about Willey was told to me by a fellow graduate student in the late 1970s. Two archaeologists were having a discussion in a bar (where else?), when who should come along but Gordon Willey. “Willey, you're just the person we need to settle this. I say that it was this way [proceeding to lay out his argument], while my colleague here says it was quite the opposite. What do you think?” After ordering a scotch-and-soda, the story goes, Gordon replied, “Well, I think you're both right!” and proceeded to lay out a marvelous synthesis incorporating the best of both arguments in a revealing new way.

Characteristically, Willey was a good sport about criticism. A lesser man might have retreated in the face of the critiques directed at Willey's perspectives during the glory days of the new archaeology, feeling wounded and personally bruised. In his memoirs Willey noted that A. V. (“Doc”) Kidder had done precisely that as a result of the intellectual assault of his work by Kluckhohn and his student Walter Taylor. Instead, Willey took in the fresh perspectives of processual archaeology, and chalked them up to the innovative and fruitful directions that American archaeology was bound to take as it expanded in scope, membership, and resulting competitiveness.

Willey never directly criticized the work of a colleague in print; it was simply not his style. Instead, he distinguished himself as a scholar who relished the achievements and appreciated the ideas of his fellow archaeologists. To the end of his long and phenomenally productive life, Willey was always a great optimist for the profession, with a marvelous sense of humor. Clearly this was a man who bore no grudges against those few who had managed to better him in one particular race or another. He loved to tell the tale that, while in track at Arizona, he had the distinction of running in a heat with the great Jesse Owens. “I had him,” he would exclaim, “for the first three steps…. After that I watched his backside.”

No one bettered Willey at producing thoroughgoing and eminently useful monographs on New World archaeology. After his work in the Southeast United States, Peru, and Panama, his Maya archaeological projects in the Belize Valley (1953–1956), Altar de Sacrificios (1958–1964), and Seibal (1964–1968) in Guatemala, and in Copan, Honduras (1975–1977) resulted in more than a dozen monographs on subjects ranging from ceramics and artifacts, to settlements and settlement patterns, to architecture and epigraphy. Willey was always the quickest of his team to produce and a superb synthesizer of the overall results of each project.

Happily for the larger field, Willey's interests in what he named the “Intermediate Area” in his great Introduction (Volume II, South America) were not altogether dampened by Tozzer's admonitions. He later went on to run digs in Nicaragua (1959, 1961) and the northeast coast of Honduras (1973). In 1971, he renewed his interest in Peru, visiting preceramic sites with his then-graduate student Michael Moseley. Their work together launched the Maritime Foundation Hypothesis and a stellar, highly productive career for Moseley in South American archaeology.

Willey's Maya work was the inspiration and leading light of several highly influential advanced seminars at the School of American Research in Santa Fe, on The Classic Maya Collapse (edited by T. Patrick Culbert, 1973), The Origins of Maya Civilization (edited by R. E. W. Adams, 1977), and Lowland Maya Settlement Patterns (edited by Wendy Ashmore, 1981). He wrote or co-authored the summary statement for all of these and the School of American Research volume on The Archaeology of Central America (edited by Frederick Lange and Doris Stone, 1984), as well as the introductory chapter for the School of American Research volume on Late Lowland Maya Civilization (edited by Jeremy A. Sabloff and E. Wyllys Andrews V, 1986).

Willey was the acknowledged master at Maya archaeology when the director of the Honduran Institute for Anthropology and History, Dr. Adán Cueva, invited him to design a long-term program of conservation and investigation of the great site of Copan, Honduras, in 1973. Once again he drew upon the expertise of his colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania Museum, in this instance, William Coe and Robert Sharer, then working just across the border at Quirigua, Guatemala. Willey's plan (published in the inaugural issue of the institute's journal, Yaxkin, with Coe and Sharer as co-authors) has served as the guiding light, a veritable beacon, for all subsequent research and site management in the Copan Valley. Although circumstances dissuaded Willey from continuing there beyond the 3 years in which he launched the modern Copan work, his intellectual vision in formulating the research problems and approaches to be pursued will be followed for many generations. I was very fortunate to be invited to join Willey's project with Richard Leventhal in the Copan Valley and, in the years following it, to attempt to follow through on various aspects of Willey's grand plan. In 1983 Gordon and Katharine made their final journey to Maya lands to visit and provide guidance to Charles Lincoln in his dissertation research at Chichen Itza, Yucatan, Mexico.

In the field, Willey would tell his students that “in order to do good archaeology, you need two things: discipline and coordination.” Discipline and coordination in the field also included following the standards and traditions set forth by the Carnegie Institution of Washington digs in the Maya world. Gordon acknowledged that he was particularly blessed to work with the master logistician and excavator, A. Ledyard Smith. Smith was the veteran of numerous excavation campaigns in the Maya lowlands and highlands, the field director of Willey's projects at Altar and Seibal, and an incomparable “steward” (Figure 5). Among many other laudable traditions, Ledyard was steadfast in maintaining the Carnegie practice of cocktail hour, every afternoon at 5 o'clock sharp. Deep in the Guatemalan rain forest with precious little else to do, small wonder that this particular ritual became so vital to everyone's physical and spiritual well-being. One of Gordon's favorite tales of his days in the field with Ledyard was when his former student R. E. W. Adams' old Marine commander, a colonel as I recall, came to inspect the camp at Altar de Sacrificios. Over lunch that day, the colonel loudly admonished “SMITH … that latrine is a disgrace to Harvard University!”

Willey (in white hat) and colleagues on the Pasion River, en route to Seibal, Guatemala, 1965. (Courtesy Peabody Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.)

In the decade following his projects in the Peten, Willey's interests in archaeological method and theory and the cumulative nature of the discipline were skillfully displayed in his edited volume, Archaeological Researches in Retrospect (1974), and the highly regarded History of American Archaeology, also published in 1974 and co-authored with his distinguished colleague and former student Jeremy Sabloff. The latter book proved so helpful to the field (and, hence, successful) that it was revised twice, in 1980 and 1993. Just as processual archaeology had challenged many of the tenets of the field that Willey had come to not only master but also in a sense personify, so too the post-processual movement called for drastic revisions in the way archaeology should be done. In the third edition of their History, Willey and Sabloff happily acknowledged the progress achieved with this new way of approaching the past, but characteristically fit it into their view of the cumulative nature of the discipline, preferring to call it “contextual archaeology.” In conversation, Willey very much enjoyed discussing the latest theoretical developments, substantive advances, and professional gossip in his chosen field. One fine day at lunch, when Bob Preucel was discussing the virtues of post-processual archaeology with Gordon and me, Gordon cleared his throat and purposefully said, smiling, “Yes, but some stories are simply better than other stories. They have more rigor and discipline and data to back them up!”

The story of the rise of Maya civilization was one that Willey himself played a large role in constructing. In his summary of the volume, The Origins of Maya Civilization (edited by R. E. W. Adams and published by the School of American Research in 1977), Willey waxed philosophical on the model they had created:

This model, as cast here, is obviously a very “historical” one. With this historicity stripped away, it places demographic pressure—in its systemic complex with ecology and subsistence productivity—in the position of prime mover or prime cause of the rise of Lowland Maya civilization. This is satisfactory up to a point. Numbers of people and their physical well-being are basic to the maintenance of any society, particularly a large and complex one. But these are self-evident truths—essentially biological conditions. Without these forces and factors, to be sure, nothing would have happened. And yet the forms that they assumed are not, to my mind, really comprehensible from so distant, so superhuman a perspective. Beyond population pressure, a drive for survival through competition represents a second level of causality. Complex social, political, and economic organizations are adaptive mechanisms for survival, but they take many forms. It is at this point that ideas and ideologies enter the picture. When we begin to consider these, and to attempt to achieve understanding on a more human scale, we come to “historical explanation”—something that is decried by some as no explanation at all. Maybe so, but in the study of human events I cannot rid myself of the feeling that this is where the real interest lies.

On a personal level, Gordon was engaging and generous, with a marvelous sense of humor and a deep appreciation of the accomplishments and character of other people. This shines through in his “Memoirs of Distinguished Americanists,” where he took pains to share his observations on the personalities, current events, and the ideas that “made” each of the colleagues who had such a strong impact on his life and his thinking. From Byron Cummings, Gordon learned the value of good teaching, of the way in which “the Dean” implicitly imparted a sense of right and wrong to his students, in addition to all the knowledge and wisdom accrued from a lifetime of study and field research. Late in life, Gordon used to joke about his own role in providing “moral guidance,” saying that his own longevity could be directly attributed to “all that good, clean living.” He also greatly admired Duncan Strong as a teacher, having learned much from him about how to teach, how to think, and how to write about larger patterns of culture change in the Americas. Willey produced dozens of doctors of philosophy during his 36 years of teaching in the Department of Anthropology at Harvard. Many of them contributed to the two superb volumes produced as a festschrift for him, Settlement Patterns in the Ancient Americas: Essays in Honor of Gordon R. Willey (edited by Evon Z. Vogt and Richard M. Leventhal, 1983) and Civilization in the Ancient Americas: Essays in Honor of Gordon R. Willey (edited by Richard M. Leventhal and Alan L. Kolata, 1983; both were published jointly by the University of New Mexico Press and the Peabody Museum). Although Willey was proud to tell people that, when he became president of Harvard's Faculty Club in the 1950s, he quickly moved to admit women, it should be acknowledged that he was much less inclined to take female archaeologists on his field projects. One may perhaps simply attribute this to an “old-fashioned,” if courtly, style that ran through his life. When presented with the two-volume festschrift and celebrated for his immense success as a mentor to so many highly accomplished scholars during his retirement dinner at the Harvard Club in Boston, Willey used a track metaphor in saying that the secret was in choosing the best people for your team. “After that,” he modestly said, “you just line them up, and let 'em go.”

Toward the end of his teaching career at Harvard, Willey zealously guarded his time as if it were the last swig of water in his canteen on a long day of archaeological survey. This included dodging further commitments at professional meetings (which he managed deftly, noting his aversion to flying), sidestepping the directorship of the Peabody Museum, and limiting his teaching to one seminar each fall, his famed 211r (for “repeatable”) Archaeology of Middle America. The participants in this seminar over the years were a virtual roll call of distinguished Mayanists (including many of Evon Vogt's students) and South Americanists, along with occasional brave souls from other fields. By the 1970s, Willey had the process of culling prospective students down to an art form. On the first day of class, usually about fifteen eager aspirants would crowd into Room 57E on the fifth floor of the Peabody Museum. Their ardor for studying with the master was enhanced by the original rendering of Proskouriakoff's map of the Maya area, hanging prominently on one wall. In would stride our impeccably dressed captain, lighting up the room with his presence, bearing a great sheaf of papers and notes. Professor Willey would march purposefully to the seat of honor at the end of the table, where the light from the window behind him provided a suitable glow behind his distinguished head. Once seated, he would briskly shuffle the papers, clear his throat, and proceed to scare the living daylights out of all those present (except the fortunate few “repeaters”) by laying out the prerequisites for the course. In a kindly tone, with one eyebrow slightly raised and only the very slightest trace of a smile, he would allow that, “Now, to be able to do well in this seminar, you'll need to already have a solid grasp of the material culture, and space–time systematics in this part of the world. You'll of course know the difference between, say, Fine Orange and Thin Orange, for example.” At that, the eyes of two or three students would get as big as saucers, and they would quietly depart. “And you'll need to control the regional sequences,” Gordon would continue, “in all parts of Mesoamerica. You know, the dates and names of the various ceramic and artifact complexes and their phasing, and the specific types that have allowed cross-referencing between them over the years.” Heads bowed, three or four more students would rise from their seats and trudge out the door.

At that point, Willey would survey the room and, if there were still people he didn't know or whom he thought couldn't handle it, delivered the coup de grace: “And as all of you are aware, I expect your term paper from this class to be of publishable quality in one of our discipline's journals, such as American Antiquity.” That was it. Whoever was courageous enough to remain seated at that point would watch the final, sadly uninitiated would-be disciples shuffle (or in one memorable case, almost run) out of the room. All alone with his latest group of intellectual seafarers, Willey would sit back in his chair, smile, and let us in on what he had in mind for the seminar that fall. It was an unforgettable experience for all whose stomachs could stand the first five minutes. (I confess that I myself almost walked out, my first time in the ritual!) The presentation of the latest unpublished work, the give and take of ideas, the lively conversations, and the masterful summary by Willey at the end of the seminar were capped off with a marvelous dinner party thrown by Katharine and Gordon at their home, 25 Grey Gardens East, located in a lovely part of Cambridge just off the former Radcliffe campus. This was easily among the happiest moments in the lives of the graduate students during their years at an institution that fosters competitiveness. Katharine delighted all her guests with her marvelous southern hospitality, never relinquishing her marvelous drawl or her roots in Macon. Gordon was ever the purveyor of grace, style, superb wit, and some very strong drinks, each of which in its own way helped put all his guests at ease. In keeping with Strong's mentoring, Gordon would always invite Tatiana Proskouriakoff, Ledyard Smith, or any colleague who happened to be in town visiting, to join in the libations, victuals, and animated exchange of ideas. Many of those ideas did make it into print, with one particularly productive seminar resulting in the volume A Consideration of the Early Classic Period in the Maya Lowlands, which Willey co-edited with Peter Mathews and published in 1985 (Institute for Mesoamerican Studies, SUNY Albany).

Willey served as the president, first of the American Anthropological Association (in 1961) and then of the Society for American Archaeology (in 1967). He was a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, a member of the Sociedad Mexicana de Antropología, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Boston, the National Academy of Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, and a Corresponding Member of the British Academy. His long list of awards included the A. V. Kidder Medal for Archaeology from the American Anthropological Association, the Order of the Quetzal from the Government of Guatemala, the Gold Medal for Distinguished Archaeological Achievement from the Archaeological Institute of America, the Viking Medal for Archaeology, the Huxley Medal from the Royal Anthropological Institute (U.K.), the Distinguished Service Award from the Society for American Archaeology, the Walker Prize from the Boston Museum of Science, the Lucy Wharton Drexel Medal for Archaeology from the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, the American Academy of Achievement, Golden Plate Award, the Florida Anthropological Society, 40th Anniversary Award, and, most recently, the Gold Medal from the London Society of Antiquaries. He was awarded honorary doctorates from his undergraduate alma mater, the University of Arizona, the University of New Mexico, and the University of Cambridge (U.K.), where he and Katharine enjoyed visiting and writing (and in Gordon's case, being fitted for suits at Savile Row) on numerous occasions.

Gordon enjoyed his retirement years in Cambridge answering correspondence and visiting colleagues in the Peabody Museum, having lunch with friends at the Long Table in the Harvard Faculty Club, and writing the occasional scholarly article or review. But in his final years Willey lavished most of his writing time on crafting archaeological mystery novels. Willey's skills as a writer and his human qualities shine in each of these works, the first of which (Selena) was published and continues to be widely read. The game is afoot to publish the remaining three novels, based in Peru, Panama, and Belize. In the acknowledgments at the beginning of all his “big books,” Willey would always express his gratitude to Katharine for her careful readings of his manuscripts and suggestions for their betterment. The two of them shared a love for literature and drama and would often read to each other late into the night. Clearly some of the wonderful turns of phrase in Willey's writing owed to Katharine's skills as a wordsmith and her appreciation of good prose. Gordon and Katharine are survived by their two daughters Alexandra Guralnick and Winston Adler, their two sons-in-law Peter Guralnick and Jeffrey Adler, and their grandchildren Jacob and Nina Guralnick and Nicholas, David, and Anthony Adler.

Across the river in Boston, Willey was a revered regular at the Tavern Club, for which he wrote many award-winning plays and served as president and keeper of the rolls. A great lover of limericks, Willey wrote many a fine one himself for his colleagues and students who continue to count them among their most prized possessions. One of the best known was about his colleague Robert Sharer's work in bringing to light the importance of the cataclysmic eruption of the Ilopango Volcano in El Salvador, just before the onset of the Classic period of Maya history:

Volcanoes are dangerous to men

So says Bob Sharer of Penn.

For when old Ilopango

Went bingo and bongo

It killed every nine out of ten!

Of his hundreds of scholarly contributions, his personal favorite was the 1976 masterwork for the British journal Antiquity, “Mesoamerican Civilization and the Idea of Transcendence.” In it, he eloquently made the case that the Toltec priest-ruler Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, of the City of Master-Craftsmen known as Tollan (present-day Tula, Hidalgo), had created a religious ideology and philosophy that was transcendent and fully on a par with the great religious traditions of the Old World.

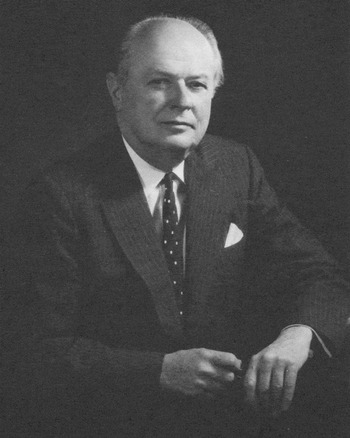

In some ways, Gordon Willey himself was a transcendent figure, creating an archaeological approach that applies to and provides revelations on peoples and cultures in all parts of the world. It was focused on the settlements—and what they reveal of the lives and times—of all members of ancient societies, from the masses to the ruling elite. On a personal level, he transcended all of the dramatically different social contexts that he experienced over the course of his long, productive, and happy life: from Iowa everyman, to sunny California youth, to track star and budding archaeologist at Arizona, to the man who survived the swamps of Florida, to partner in Jim Ford's relentless surveying in Viru, to dapper Harvard professor, beloved Taverner, and mystery novelist. Gordon Willey will live on happily in the memories of all who knew him, through the wonderful tales he told, the courteous cupping of his hand on your elbow to guide you through a door, the hilarious manglings of pronunciations that made us all laugh at our folly and the trials of the human condition, the timely words of advice and always, and the appreciation for the character and accomplishments of others. Even though the tradition of Mesoamerican scholarship that was entrusted to him will live on at Harvard, his passing will be difficult for all of us who knew him, because Gordon Willey personified so much that was good and lasting in the Peabody Museum. With his impeccable taste—“I love suits,” he was fond of saying—his gold pocket watch and chain, and his jaunty walk (even when assisted with a cane, in his later years), he was as distinctive and distinguished as the institution he was so proud to serve (Figure 6). The hundreds of scholars who were the recipient of his thoughtful handwritten letters, and those who had the privilege him of knowing him personally, will forever be in his debt. His former students admired him for his generosity, his modesty, and his integrity; almost all of them just feel fortunate to have known him. Beyond our own times, lives, and memories, Willey's scholarly work—the transcendent syntheses, the charting of the course—will likely be cited in the sacred texts of his chosen field for centuries to come.

Studio portrait of Gordon R. Willey, 1981. (Courtesy Peabody Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.)

How to close a woefully incomplete remembrance of such a superb scholar and human being? In reminiscing about his former boss, fine colleague, and close friend Matthew Stirling, Willey remarked that he believed that Stirling was not sufficiently appreciated until after he was gone. Fortunately, Willey was the recipient of many honors and was constantly being shown further measures of appreciation for his contributions to American archaeology. But his words regarding Stirling apply equally well to Gordon Willey himself: “[Those] who knew him, remembered his leadership, his unruffled perseverance, his many kindnesses, and that quiet greatness which underlay his modesty.”