Introduction

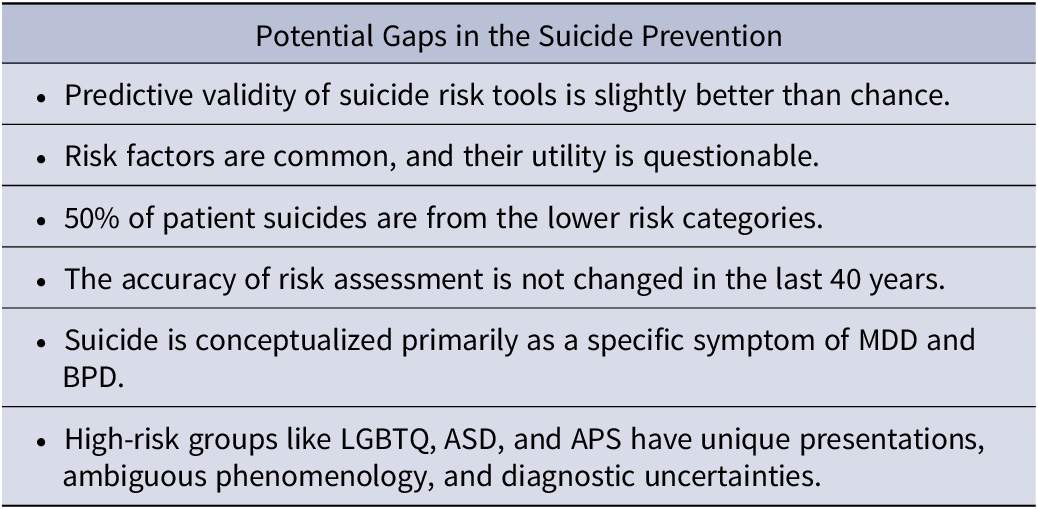

The worldwide suicide rate for 10 to 19-year-old is around 3.77/100 000. The rate of suicides among age 10 to 24 increased nearly 60% between 2007 and 2018.Reference Curtin, Warner and Hedegaard 1 In the last two decades, there is a significant increase in knowledge of the warning signs, risk factors, systematic screening, and use of risk assessment scalesReference Carballo, Llorente and Kehrmann 2 . Although suicide is a rare sentinel event; about 45% of those who died by suicide saw a primary care physician 30 days before they died. The Joint Commission (TJC) reported the failure to assess suicide risk was the most common root cause of suicides qualifying as sentinel events. A central and most compelling but still unanswered question remains why after decades of research the suicides rate is rising? Do these patients have an atypical presentation with highly confounding variables which are linked with these serious events? The critics of psychiatry have made repetitive claims that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is still classifying mental disorders based on their surface appearance, not on their underlying biology. And the history of science shows that appearances can be deceiving. The prediction ability of the existing suicide risk tools from the last 50 years is only slightly better than chance Area under the (Receiver Operating Characteristic) ROC Curve (AUC = 0.56-0.58).Reference Franklin, Ribeiro and Fox 3 The known risk factors are so common that their utility has been questioned and may paradoxically increase the rates since the engagement is less due to elevated clinician anxiety. About 95% of high-risk patients will not die by suicide, 50% of suicides came from the lower risk categories and there was no improvement in the accuracy of risk assessment over the last 40 years.

Suicidal thoughts are considered a symptom not specific to a particular disorder. Since the introduction of DSM III, the categorical classification of symptoms into diagnosis has replaced the historical practice of understanding the meaning of the symptoms. The UK advisory body and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommended “assessment tools and scales designed to give a crude indication of the level of risk (eg, high or low) of suicide” should not be used. Several studies have shown that higher number of male adolescents died by suicide as compared to females, which is replicated in cross-cultural studies. However, factors behind higher suicide rate in males as compared to females could not be explained, nor does why nonaffective illness is not represented in the data. Suicide has multifactorial etiology and suicidal thoughts are considered a symptom not specific to a particular disorder or illness. Suicidal risk assessments are more skewed toward affective illness and often overlook co-occurring phenomenology or etiology.

Given in the DSM-5 suicide is conceptualized primarily as a specific symptom of major depressive disorder (MDD) and borderline personality disorder (BPD), which takes the focus away from other conditions. The major gap with these strategies is an over-reliance on symptoms reported by the patients, failure to recognize patients’ resistance in sharing information, ignoring the clinical context of the symptoms, and lastly not ruling out the possibility of co-occurring nonaffective illness. Although in the last decade, the knowledge of risk factors has been more nuanced, but given the scope of the problem, there is consensus among researchers that it is a systemic failure.

Three such high-risk groups meet the above description. Firstly, undisclosed sexual minority adolescents or lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) group. Secondly, undiagnosed high-functioning autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and lastly adolescents with undiagnosed prodromal or attenuated psychosis (APS). There are some valid and compelling clinical arguments for these observations.

Sexual Minority Youths (LGBTQ)

In 2012, the U.S. Surgeon General identified increased suicide risk in LGBT youth, with studies reporting 2 to 4 times heightened risk for suicidal ideation and attempts. The sexual minority had 3 to 6 times greater risk than heterosexual adults across every age group and race/ethnicity category. The high schooler, who identified as LGB had seriously considered suicide (42.8%), planned suicide attempt (38.2%), attempted suicide at least once (29.4%), or were injured due to suicide attempt that required treatment by health care professionals (9.4%). The high suicide risk is largely attributed to depression, substance use, feeling unsafe at school, or insufficient social support. LGBTQ youth often face “minority stress,” stress from prejudice, stigmatization, and discrimination, and are victimized for their sexual orientation or gender identity. These high-risk populations require more attention as lack of disclosure is common and specific screenings of these individuals are lacking.

High-Functioning ASD

There is a threefold higher risk of suicide attempt and suicide in individuals diagnosed with ASD and aged over 10 yearsReference Zahid and Upthegrove 4 . Psychiatric comorbidity is a major risk factor, with studies reporting over 90% of ASD suicide cases have co-occurring disorders. Camouflaging in females with autistic traits is also linked with cognitive exhaustion, depression, and/or stress and thoughts of suicide. The late diagnosis of high-functioning ASD in females, its unique presentations is suggestive of a distinct female phenotype. The behavioral activation related to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) is often underestimated.

Prodromal Psychosis or APS

The rate of suicidal ideation and the suicide attempt is 25.5% and 7.5%, respectively which is 3.8-fold and 8-fold higher.Reference Andriopoulos, Ellul, Skokou and Beratis 5 Adolescents with an insidious decline in functioning could be indistinctive with affective illness. Therefore, the diagnosis of prodromal psychosis could be extremely challenging. Studies have established that hopelessness could be a predictor of suicide in one with the first admission with psychosis. These patients would not respond to SSRI or cognitive behavior therapy and are at high risk for substance use. In many instances, low-dose antipsychotics are used for augmenting the SSRI regimen. Patients with partial response to the brief treatment with antipsychotic medications are at even higher risk. Depressed mood, impaired functioning, and tobacco smoking are reported to be independent predictors of suicidal ideation in prodromal psychosis, whereas the predictive factors for suicide attempts include depression and younger age of onset (Table 1).

Table 1. Recent Empirical Research has Questioned the Use of Risk Factors in Suicide Prevention.

The validity of the risk assessment tools has not improved and many who complete suicide are from lower-risk categories. The assessment for special high-risk groups based on the emerging data could address the gaps amidst child and adolescent mental health crises.

Abbreviations: APS, attenuated psychosis; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; BPD, borderline personality disorder; LGBTQ, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer; MDD, major depressive disorder.

Discussion

It is established based on the empirical evidence that the knowledge of risk factors, use of risk assessment tools, and multifaceted mitigation strategies are key to the current suicide risk management guidelines or practice recommendations. The use of tools like the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ 9) and Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) has demonstrated an overall reduction in the negative outcomes. The elimination of lethal means, engagement with motivational enhancement strategies, and development of safety plans are all effective evidence-based interventions.

However, we highlight the need to discern the possibility of the confounding variables and their inclusion in the assessment. The issues could arise both due to lack of disclosure from the patient and ambiguity about the clinical presentation. The patient’s reluctance to disclose could be due to stigma, fear of affecting their relationship with the family.

As per the recent epidemiologic studies, the prevalence of ASD has been as high as 1:43. It is likely that many adolescents failed to get diagnosed earlier and during mid-adolescence when they struggle to make social connections. They are often bullied due to a lack of social skills which on many occasions triggers mental health crises. The lack of understanding of symptoms as the clinical presentation does not quite fit the DSM criterion, poor response to SSRI and behavioral activation are possible reasons. The emerging evidence suggests camouflaging behind for late diagnosis of ASD in females. The patients with ASD would often do meticulous research for suicide, and during the assessment, the depth of research or thoughts of using lethal means to attempt suicide may give cues to the underlying psychopathology.Reference Cassidy, Bradley, Shaw and Baron-Cohen 6 The prodromal psychosis often fails to respond to treatment as usual for affective illness and an insidious decline in overall functioning with new-onset paranoia, lack of self-care, and social withdrawal could be the subtle clues. In 1929, Sigmund Freud wrote a book “Civilization and Its Discontents” published in German in 1930 as Das Unbehagen in der Kultur (“The Uneasiness in Civilization”) which underscores the societal needs of conformity and any deviance in youth’s desires are banished with the feeling of shame and guilt. In the 21st century society to struggle with similar crises as we continue to admonish sexual minority youths with a moral compass that affects the development of self and identity as described by Kohut and Erikson. It may be appropriate to rescreen for ASD with more sophisticated instruments for at-risk individuals given the stakes are very high. Lastly, insidious onset of illness with social withdrawal must be always explored for any perceptual disturbances and a subtle sign of APS.

Given the rise in adolescents’ suicide rates; the current preventive measures have raised many uncomfortable questions. There are many gaps as confounded clinical phenomena do not raise the red flags. The complex psychophenomenology, shame and guilt, false-negative ASD screening, and lastly, extremely distressing attenuated psychosis where teens’ inability to explain symptoms are few among many plausible explanations. The researchers and policymakers may consider liaising with clinicians working closely with children and adolescents to address these gaps in the future course of research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: D.R. and M.G.; Data curation: M.G.; Formal analysis: M.G.; Writing – review & editing: N.G.; Writing – original draft: M.G.

Disclosures

The authors do not have anything to disclose.