Childhood obesity is a major public health issue in Canada given its widespread prevalence and negative impact on health(1). Genetic, environmental and socio-ecological factors contribute to the development of childhood obesity(Reference Kumar and Kelly2) with parents establishing the food environment at home, thereby influencing children’s food choices, eating habits and energy intake(Reference Scaglioni, De Cosmi and Ciappolino3). Consequently, it is recommended that parents be involved in interventions to prevent and/or mitigate childhood obesity(Reference Pamungkas and Chamroonsawasdi4). Engagement of parents requires an understanding of parental perceptions and practices regarding child weight and feeding as they may have an impact on the effectiveness of these interventions(Reference Kumar and Kelly2).

Parental perceptions of their children’s weight influence children’s weight over time. Indeed, longitudinal studies suggest that children whose parents perceived them as having overweight or obesity were more likely to gain and maintain excess weight over time(Reference Gerards, Gubbels and Dagnelie5–Reference Robinson and Sutin7). One study showed that children living with overweight or obesity who were perceived as having overweight or obesity by their parents were more likely to have a higher increase in BMI from age 5 to 9 compared to children with overweight or obesity who were not perceived as such(Reference Gerards, Gubbels and Dagnelie5). An Australian longitudinal study reported that parental perceptions of overweight among children predicted more weight gain across 8 years of follow-up compared with parental perceptions of normal weight among children(Reference Robinson and Sutin6). Similarly, Robinson and Sutin(Reference Robinson and Sutin7) examined two different cohorts (age: 4–5 to 14–15 and 9–13 years old) and found that parental perceptions of overweight were associated with greater weight gain during follow-up. Interestingly, results from these three studies were significant whether parental perception was accurate or not, meaning that normal-weight children and children with overweight or obesity who were perceived as having overweight or obesity by their parents gained more weight than children who were not perceived as having overweight or obesity(Reference Gerards, Gubbels and Dagnelie5–Reference Robinson and Sutin7). Authors suggested that parental perception of overweight and obesity could increase the risk of weight gain because of the stigma associated with this perception(Reference Robinson and Sutin6–Reference Hunger and Tomiyama8), which may result in the adoption of counterproductive strategies to reduce children’s weight(Reference Robinson and Sutin6,Reference Robinson and Sutin7) , such as the use of restrictive feeding practices. These counterproductive feeding practices are associated with excessive weight gain in the long run(Reference Spill, Callahan and Shapiro9,Reference Tschann, Martinez and Penilla10) . Children perceived as having overweight or obesity are also more likely to perceive themselves as having overweight or obesity and to unsuccessfully attempt to lose weight(Reference Robinson and Sutin7,Reference Abdalla, Buffarini and Weber11) . Consequently, these studies highlight the need to shift the field from understanding determinants of parental misperception (or underestimation) towards understanding determinants of parental perception of children’s weight per se (i.e. whether it is accurate or not)(Reference Gerards, Gubbels and Dagnelie5–Reference Robinson and Sutin7). Authors of a recent systematic review reached a similar conclusion(Reference Blanchet, Kengneson and Bodnaruc12). Yet, to our knowledge, no study has examined factors associated with parental perceptions of children’s weight status per se.

Parental practices regarding child weight and feeding also seem to be associated with parental concerns about child weight(Reference Scaglioni, De Cosmi and Ciappolino3,Reference Moore, Harris and Bradlyn13,Reference Seburg, Kunin-Batson and Senso14) . Parental concerns about child weight were associated with parents’ use of strategies to promote healthy child weight, such as increasing physical activity or limiting screen time(Reference Moore, Harris and Bradlyn13). However, the literature also suggests that mothers who were concerned about their children’s weight and risk of gaining excess weight were more likely to use restrictive and pressure to eat feeding practices(Reference Scaglioni, De Cosmi and Ciappolino3,Reference Seburg, Kunin-Batson and Senso14) . These feeding practices were previously determined not only to have a negative impact on children’s diet quality but were also associated with excessive weight gain over time(Reference Spill, Callahan and Shapiro9,Reference Tschann, Martinez and Penilla10,Reference Entin, Kaufman-Shriqui and Naggan15) . Although parents whose children have overweight or obesity are more likely to be concerned about their children’s weight, children’s age(Reference Crawford, Timperio and Telford16,Reference Wald, Ewing and Cluss17) and gender(Reference Moore, Harris and Bradlyn13,Reference Hernandez, Reesor and Machuca18,Reference Peyer, Welk and Bailey-Davis19) , as well as parental weight status(Reference Peyer, Welk and Bailey-Davis19–Reference Hernandez, Reesor and Kabiri21), region of origin(Reference Regber, Novak and Eiben22) and education level(Reference Nowicka, Sorjonen and Pietrobelli23) also contribute to these concerns. In contrast, parental age, socio-economic status and marital status were found not to be associated with parental concerns about child weight(Reference Scaglioni, De Cosmi and Ciappolino3,Reference Hernandez, Reesor and Machuca18,Reference Hernandez, Reesor and Kabiri21) .

Children’s diet quality can be assessed by quantifying food intake and comparing it with dietary intake recommendations(Reference Jessri, Nishi and L’Abbé24). However, with the increasing availability and consumption of ultra-processed products (UPP), such as junk food, researchers have started to focus on food processing and its impact on health(Reference Juul, Martinez-Steele and Parekh25–Reference Moubarac, Batal and Louzada27). UPP have poor nutritional values with UPP intake identified as an indicator of poorer diet quality(Reference Moubarac, Batal and Louzada27).

Published studies examining parental perceptions and concerns related to children’s weight status have been conducted among various populations, but mainly among White families(Reference Blanchet, Kengneson and Bodnaruc12,Reference Regber, Novak and Eiben22) . Studies have suggested that Black parents were less likely to perceive their child as having overweight or obesity and less likely to be concerned about child weight compared with White or Latino parents(Reference Anderson, Hughes and Fisher28–Reference Cachelin and Thompson30). However, these studies were mostly conducted in the USA with relatively small samples of African Americans and/or Blacks. Similarly, studies on UPP consumption have been mainly conducted among Latino and White populations(Reference Vandevijvere, Jaacks and Monteiro31,Reference Elizabeth, Machado and Zinöcker32) . In Canada, Black people represent 3·5 % of the population. In Canada, most Black people are immigrants (56·4 %) or children of immigrants (35·0 %), primarily from Sub-Saharan Africa and the Caribbean(33). Thus, the experience of most Black people in Canada is shaped by their intersecting identities as racialised minorities and by their diverse immigration experience (or that of their parents)(34). Upon arrival to Canada, Black immigrants face several discrimination-related challenges particularly regarding foreign credential recognition, employment and housing which often lead to a lower socio-economic status than the main population, and consequently, a deterioration of their health(Reference Houle35,Reference Do36) . For example, Black immigrants generally exhibit better health than Canadian-born upon arrival; however, their risk of developing chronic diseases such as obesity increases over time and surpasses that of their Canadian counterparts(Reference Vang, Sigouin and Flenon37,Reference McDonald and Kennedy38) . Determinants of Black immigrant people’s health, including factors associated with parental perceptions and concerns about their children’s weight status, are under-researched in Canada and worldwide(34). Further, examinations of feeding practices, perceptions and concerns within Black families have generally not considered the heterogeneity within Black communities, including factors such as immigration status. The heterogeneity of both the African and Caribbean diaspora precludes an in-depth evaluation of the roles of culture and heritage on feeding practices, perceptions and concerns. As such, findings from other studies are limited and not generalisable to the Canadian context because of the interplay of ethnicity, migration and socio-economic factors. Therefore, this research was designed to explore the relationships between maternal immigration experiences and children’s weight status in Black Sub-Saharan-African and Caribbean mothers living in Canada. More specifically, the purpose of this study was to: (1) identify factors influencing Black immigrant mothers’ perceptions and concerns about child weight and (2) compare children’s energy intake and diet quality according to mothers’ perceptions and concerns about child weight.

Methods

Participants

Mothers were recruited in Ottawa, Canada, between January 2014 and April 2015 through word of mouth, community events and with the help of ethnocultural associations and community organisations(Reference Blanchet, Sanou and Nana39). Mothers, not fathers, were recruited in this study due to their preponderant implication in children’s diet in this population(Reference Khandpur, Blaine and Fisher40,Reference McHale, Crouter and McGuire41) and the high prevalence of lone mothers in these groups due in part to immigration and consequent family separation(42). Mothers were included if they self-identified as Black; were born in Sub-Saharan Africa or the Caribbean; could have a conversation in English or French; had at least one child aged 6–12 years and resided in Ottawa. When more than one school-age child from the same household was eligible, one child was randomly selected. Three mothers born in Canada were included as they had African or Caribbean parents and spent their childhood in Sub-Saharan Africa or the Caribbean before coming back to Canada as adults. The sample included 188 mother–child dyads.

Procedure

Surveys were administered in-person by registered dietitians to mother–child dyads with the help of a trained research assistant when possible. Surveys were conducted in English or French, according to mothers’ language preferences. Each mother received a $25 CAD grocery gift certificate as compensation for the time and the cost involved in their participation.

Positionality

Authors from this study position themselves as academics and community researchers with great research interests and experience working with populations at high risk of health inequities, including minority and racialised communities. We share a commitment to nutrition and health equity and strongly believe everyone in Canada should have equal access to conditions conducive to good nutrition and health. Our interdisciplinary team is composed of Sub-Saharan African Black immigrants, Canadians, Lebanese-Canadian and first-generation Caribbean-Canadian with different experiences and expertises, which could have influenced our perspective and approach to this study.

Measures

Demographic and socio-economic data(43)

Mother (age, region of origin, marital status, education level, employment status, immigration category, length of time spent in Canada), child’s (gender, age) and household (number of children in the household, income, receipt of social or government assistance, food insecurity status) characteristics were collected using surveys. The Household Food Security Survey Module was used to assess household food insecurity status based on its eighteen items(43). Households with no affirmative answers were categorised as food secure while households with one or more affirmative answers were categorised as food insecure(44). Mothers’ arrival date in Canada and the interview date were used to calculate each mothers’ length of time spent in Canada and to classify them as recent immigrants (≤ 5 years) or settled immigrants (≥ 5 years).

Children and maternal anthropometric data

Mothers’ and children’s anthropometric data were measured according to the WHO guidelines(45). Weight was measured with a calibrated digital scale (LifeSource ProFit UC-321, A&D Medical) to the nearest 0·1 kg. Height was measured with a portable stadiometer (Charder HM200P Portstad, Charder Electronic Co.) to the nearest millimetre. Measurements were done twice and averaged to increase measurement reliability. Participants’ BMI was calculated (kg/m2). Mothers’ weight status was obtained using the WHO references(45). WHO Growth Charts for Canada were used to assess BMI-for-age-and-sex z-scores then children’s weight status(46). Underweight categories from the study were excluded for mothers and children because only one mother and one child were classified as such, which left us with a final sample of 186 dyads included in this study. Mothers who were breast-feeding or pregnant (n 9) were excluded from anthropometric analyses only. Anthropometric data were missing for ten mothers and two children. Therefore, anthropometric data of 167 mothers and 184 children were available for analysis.

Body shape perceptions

Age-appropriate and sex-specific figure rating scales adapted by Stevens et al.(Reference Stevens, Story and Becenti47) were used to assess mothers’ perception of their children’s body shape. The eight silhouettes were grouped into four categories: underweight (silhouettes #1 and #2), normal weight (silhouettes #3 and #4), overweight (silhouettes #5 and #6) and obesity (silhouettes #7 and #8). Maternal perceptions of obesity were merged into perceptions of overweight as only three children were perceived as having obesity by their mothers. We also combined underweight and normal weight categories to increase statistical power(Reference Bangdiwala, Bhargava and O’Connor48). Mothers’ misperception of children’s weight status was determined by comparing perceived and measured children’s weight status (see online Supplementary Material).

The Child Feeding Questionnaire

The Child Feeding Questionnaire was used to assess maternal concerns about her child’s risks of becoming overweight(Reference Birch, Fisher and Grimm-Thomas49). Translation and back translation were used to obtain a French version of the Child Feeding Questionnaire(Reference Maneesriwongul and Dixon50). The three Child Feeding Questionnaire’s questions related to parental concerns about child weight (i.e. How concerned are you about your child eating too much when you are not around? How concerned are you that your child will have to diet to maintain a desirable weight? How concerned are you about your child’s weight in the future?) were answered on five-point Likert scales ranging from unconcerned to very concerned. The score of each question was added, and an average score was calculated(Reference Birch, Fisher and Grimm-Thomas49). To facilitate interpretation, scores were dichotomised as unconcerned (scores < 2) and concerned (scores ≥ 2) based on the distribution to have two groups of similar size.

Children’s diet quality

Children’s food intake was assessed with a 24-h dietary recall using the Health Canada standardised protocol(51). Questions were directed at children, and mothers could intervene to provide additional information about food preparation and ingredients. The 24-h dietary recalls were analysed with ESHA Food Processor SQL version 11.0.137 (ESHA Research). Nutrient contents, including the total energy intake in kilocalories (kcal) of the foods and beverages consumed, were obtained from the Canadian Nutrient File(52) and other sources when needed (e.g. US Department of Agriculture database). The NOVA Food Classification system was used to assess children’s diet quality in relation to foods and beverages’ level of processing(Reference Monteiro53). In this system, foods are classified into four groups according to their level of processing: (1) unprocessed or minimally processed foods, which are fresh or whole foods such as fruits, vegetables, meats and eggs with no industrial processing, (2) processed culinary ingredients such as salt, sugar and oils often extracted and refined from unprocessed or minimally processed foods or from nature, (3) processed foods which are foods minimally processed to increase their durability or to make them more palatable (e.g. simple cheeses, cured meats, preserved fruits and vegetables) and (4) UPP, which are industrial formulations derived from foods and containing ingredients and substances such as colourings, emulsifiers or artificial flavours that are not found in a traditional kitchen (e.g. soft drinks, industrial bread, confectioneries, etc.)(Reference Monteiro53). Dietary supplements were excluded from the classification. The relative consumption of the total daily energy intake (in percentage) provided by unprocessed or minimally processed foods and by UPP groups was estimated(Reference Moubarac54).

Data analysis

SPSS IBM for Windows version 25 was used for statistical analyses(55). Means, standard deviations and frequencies (%) were used to describe data. Pearson χ 2 tests coupled with Bonferroni post hoc tests were performed to examine factors associated with maternal perceptions and concerns about child weight. Factors examined were children’s age, gender and weight status, mothers’ age, marital status, weight status, employment status, education level, immigration status, length of time spent in Canada, region of origin and household income, receipt of social or government assistance, number of children in the household and food insecurity status. Variables with a P value < 0·25 in Pearson χ 2 tests were included in multivariable regression models(Reference Bursac, Gauss and Williams56) to identify predictors of maternal perceptions of children’s weight status (1 = child perceived as having overweight, 0 = child perceived as normal weight) and concerns about child weight (1 = concerned, 0 = unconcerned). Children’s weight status was subsequently included in models due to its known effect on parental perceptions and concerns about child weight. OR, 95 % CI and P value were calculated for every model. To examine the robustness of results related to concerns about child weight, we conducted multivariate regression models using continuous scores to examine whether the same patterns of results would be identified, and this was broadly the case (data not shown). t Tests were conducted to compare children’s daily energy intake and diet quality according to mothers’ perceptions of children’s weight status and concerns about child weight(Reference Greenland, Senn and Rothman57). Factors influencing mothers’ misperceptions of children’s weight status and comparison of children’s daily energy intake and diet quality according to mothers’ misperceptions of children’s weight status were also studied, and results are presented in online Supplementary Material. All assumptions for χ 2 tests, regression models and t tests were checked and respected. Significance level was set at P < 0·05 for all analyses.

Results

Sample characteristics

The sample comprised mostly settled immigrant participants (66·5 %) born in Sub-Saharan Africa (66·7 %) and the Caribbean (33·3 %) (Table 1). An important proportion of the sample experienced household food insecurity (44·0 %) and were refugees or asylum seekers (38·4 %). Children were on average 8·8 (sd 1·98) years old and over 54 % of mothers were under 40 years old. The sample comprised a similar proportion of girls (50·5 %) and boys (49·5 %). The combined prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity was 48·9 %. One-third of mothers (32·3 %) perceived their children as having overweight. Children’s weight status was misperceived by 51·6 % of mothers, with 47·8 % underestimating their children’s weight status (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1).

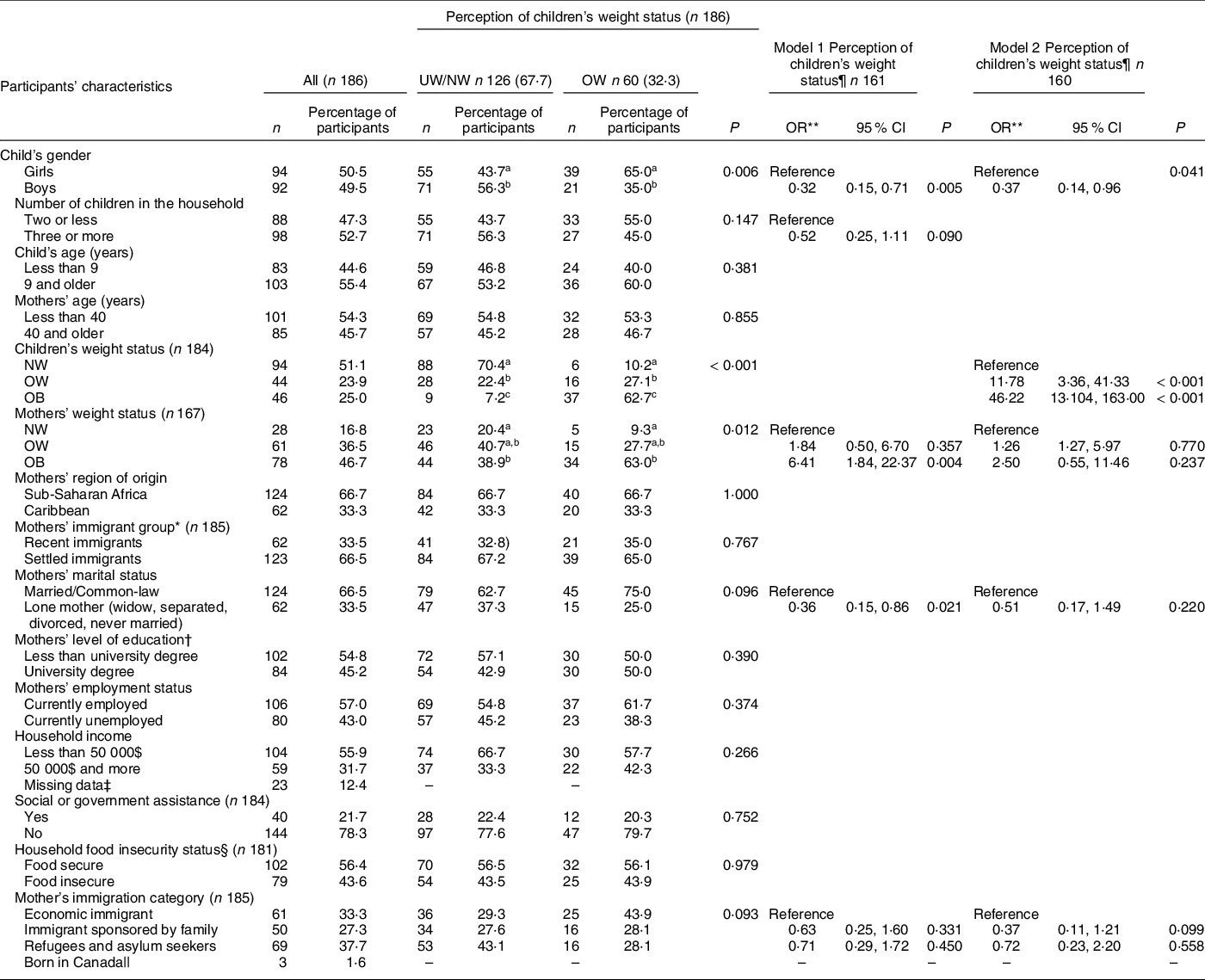

Table 1 Association between participants’ characteristics and mothers’ perception of children’s weight status

UW, underweight; NW, normal weight; OW, overweight; OB, obesity.

Model 1: child’s gender, mother’s weight status, mother’s marital status, mother’s immigration status.

Model 2: child’s gender, children’s weight status, mother’s weight status, mother’s marital status, mother’s immigration status.

a,b,cRepresents statistically significant difference between subgroups (P < 0·05).

* Mothers’ immigrant group was based on the length of time spent in Canada. In this study, ‘recent immigrants’ refers to immigrants who have spent less than 5 years in Canada and ‘settled immigrants’ refers to immigrants who had spent more than 5 years in Canada.

† Mothers’ education level completed anywhere, whether in Canada or elsewhere.

‡ Missing data were not included in the Pearson χ 2 test.

§ Households were classified as either food secure (score = 0) or food insecure (score = 1–18).

|| Born in Canada not included in the Pearson χ 2 test and the regression models.

¶ Coding for child’s weight perception in the multivariate logistic regression: underweight/normal weight = 0 and overweight/obesity = 1.

** OR were calculated in the logistic regression.

Factors associated with perceptions of children’s weight status

As shown in Table 1, girls were more likely to be perceived as having overweight than boys (P = 0·011). Mothers of children with overweight and obesity were significantly more likely to perceive their children as having overweight than mothers of normal-weight children (P < 0·001). Mothers living with obesity, but not with overweight, were similarly more likely to perceive their child as having overweight than normal-weight mothers (P = 0·012 and P > 0·05, respectively).

The multivariable regression models exploring predictors of maternal perception of children’s weight status are presented in Table 1. A first model was explored in which children’s gender, mothers’ weight status, marital status and immigration category and number of children in the household were included. Model 1 showed that children’s gender, mother’s weight status and marital status were significant predictors of the mothers’ perceptions of children’s weight status, whereas mothers’ immigration status and the number of children in the household were not. This first model accounted for 24 % of the variance. When this model was further adjusted for children’s weight status (model 2), only children’s gender and weight status remained as significant predictors of maternal perception of children’s weight status. Mothers of girls were almost four times more likely to perceive them as having overweight compared with mothers of boys (P = 0·041). Additionally, compared with mothers of normal-weight children, mothers of children with overweight (P < 0·001) and mothers of children with obesity (P < 0·001) were more likely to perceive their children as having overweight. Model 2 accounted for 56 % of the variance.

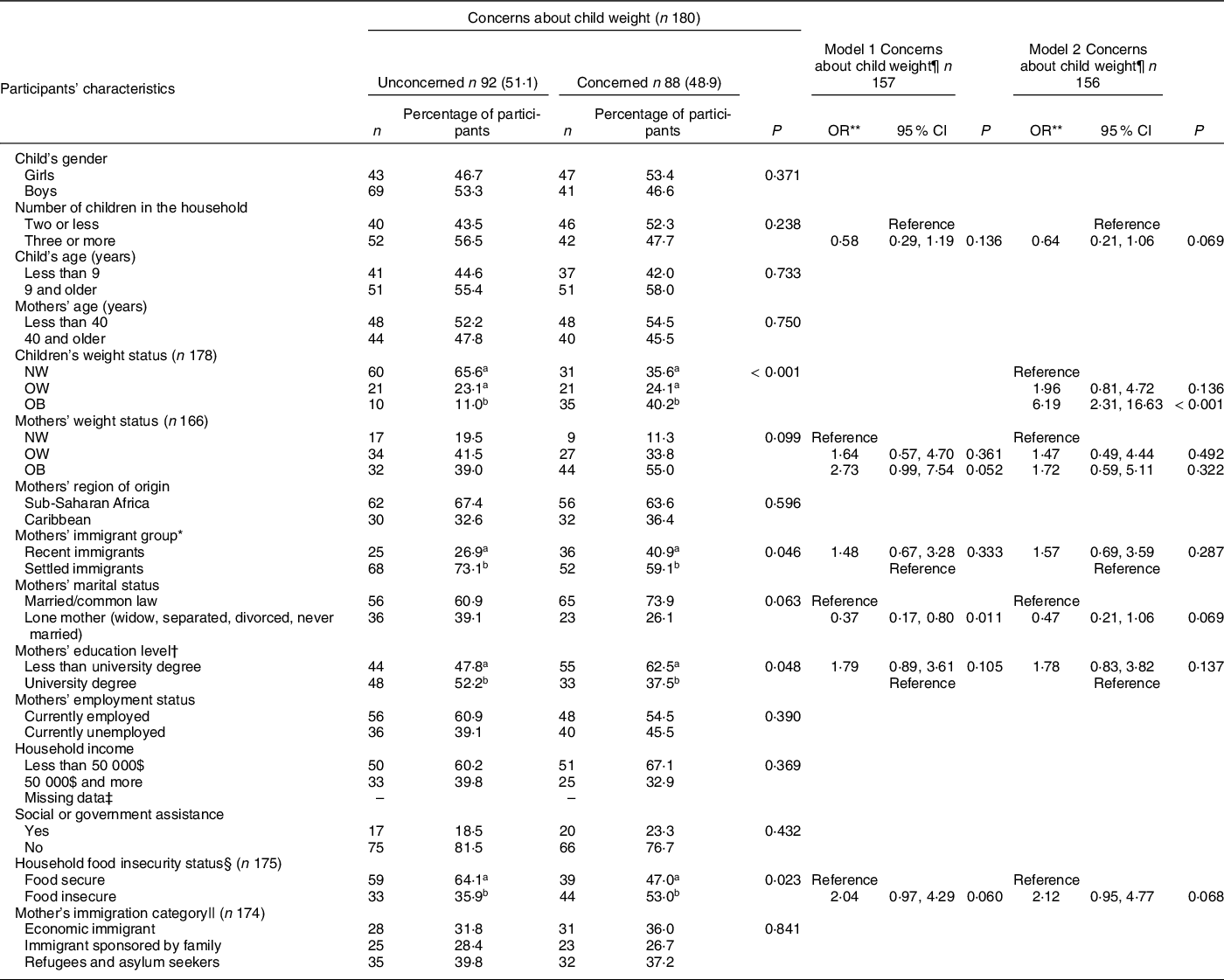

Factors associated with concerns about child weight

About half of the participating mothers (48 %) were concerned about their children’s weight status. Children’s measured weight status, mothers’ length of time spent in Canada and household food insecurity status were significantly associated with maternal concerns about child weight (Table 2). Mothers of children with obesity were more likely to be concerned about their children’s weight than mothers of normal-weight children and mothers of children with overweight (P < 0·001). Mothers of children with overweight were as likely to be concerned as mothers of normal-weight children. Settled immigrant mothers, mothers who did not have a university degree and mothers living in food-insecure households were more likely to be concerned about their children’s weight status than their counterparts (P = 0·046, 0·048 and 0·023, respectively).

Table 2 Association between participants’ characteristics and mothers’ concerns about child weight

UW, underweight; NW, normal weight; OW, overweight; OB, obesity.

Model 1: mother’s weight status, mother’s immigration group, mother’s marital status, mother’s level of education, household food insecurity status.

Model 2: children’s weight status, mother’s weight status, mother’s immigration group, mother’s marital status, mother’s level of education, household food insecurity status.

a,b,cRepresents statistically significant difference between subgroups (P < 0·05).

* Mothers’ immigrant group was based on the length of time spent in Canada. In this study, ‘recent immigrants’ refers to immigrants who have spent less than 5 years in Canada and ‘settled immigrants’ refers to immigrants who had spent more than 5 years in Canada.

† Mothers’ education level completed anywhere, whether in Canada or elsewhere.

‡ Missing data were not included in the Pearson χ 2 test.

§ Households were classified as either food secure (score = 0) or food insecure (score = 1–18).

|| Born in Canada not included in the Pearson χ 2 test and the regression models.

¶ Coding for child’s weight perception in the multivariate logistic regression: unconcerned = 0 and concerned = 1.

** OR were calculated in the logistic regression.

The multivariable regression models exploring predictors of maternal concerns about child weight are presented in Table 2. A first model was explored in which mothers’ weight status, mothers’ marital status, level of education, length of time spent in Canada, number of children in the household and household food insecurity status were included. In this model, which accounted for 17 % of the variance, mothers’ marital status was the only significant predictor of maternal concerns. When this model was further adjusted for children’s weight status (model 2), only children’s weight status significantly predicted mothers’ concerns about child weight. Mothers of children with obesity, but not with overweight, were three times more likely to be concerned about their children’s weight than mothers of normal-weight children (P < 0·001 and P > 0·05, respectively). Model 2 accounted for 28 % of the variance.

Children’s diet quality

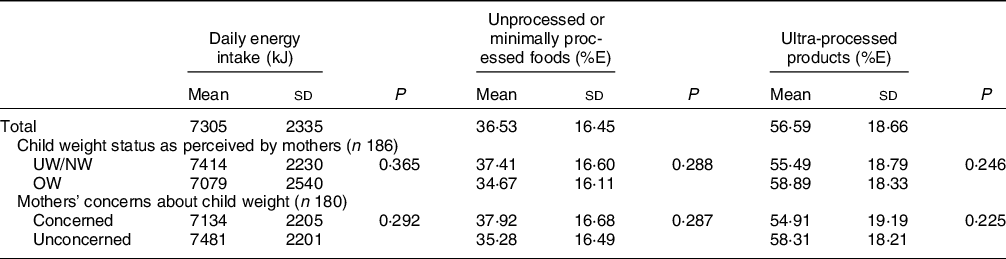

Children consumed on average 7305 kJ (1746 kcal) during the reference day, with about 37 and 57 % of their total daily energy intake coming from unprocessed or minimally processed foods, and from UPP, respectively (Table 3). There was no difference in children’s energy intake nor the relative consumption of the total daily energy intake provided by unprocessed or minimally processed foods and UPP according to mothers’ concerns about child weight and perceptions of children’s weight status (Table 3).

Table 3 Comparison between children’s daily energy intake and intake from NOVA food groups according to maternal concerns and perceptions of children’s weight status

%E, percentage of energy intake from the NOVA groups; UW, underweight; NW, normal weight; OW, overweight.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine predictors of Black immigrant mothers’ perceptions of children’s weight status and concerns about child weight in Canada and to compare children’s diet quality according to these perceptions and concerns about child weight. One-third of participating mothers perceived their children as having overweight, which is higher than what was found in a previous study conducted on parental perceptions of Canadian parents and their children(Reference Karunanayake, Rennie and Hildebrand58). Nearly half of participating mothers were concerned about their children’s weight, which contrasts with other studies reporting that Black parents were less likely to be concerned about child weight than White parents(Reference Anderson, Hughes and Fisher28–Reference Cachelin and Thompson30). Results from the present study also provide evidence that characteristics related to children, mothers and their households influence mothers’ perceptions and concerns about their children’s weight status, as discussed below.

Although there were no significant differences in measured weight status according to children’s gender (data not shown), Black immigrant mothers of girls were more likely to perceive their children as having overweight than mothers of boys. This difference in perception according to children’s gender is consistent with results from one study conducted on a predominantly White population in the USA(Reference Wald, Ewing and Cluss17). Ling et al. have suggested that gender differences in weight perceptions could be due to body composition as girls tend to have higher amounts of body fat than boys, thus, could be more likely to be perceived as having overweight(Reference Ling and Stommel59,Reference Kirchengast60) . Other authors who have also noted a gender difference in parental perceptions of children’s weight have also suggested that gendered beauty standard and weight stigma applied to girls might also have a role to play in these gendered perceptions(Reference Karunanayake, Rennie and Hildebrand58,Reference Ling and Stommel59,Reference Sand, Lask and Hysing61) . Such gendered perceptions should be further investigated among Black mothers from a variety of cultural backgrounds and their impacts on children’s weight status.

Black immigrant mothers of children with overweight or obesity were significantly more likely to perceive them as having overweight than mothers of normal-weight children. However, the fact that perceptions of overweight and obesity were combined and should be considered along with this interpretation. Indeed, the vast majority of mothers of children with obesity classified their children as having overweight rather than obesity (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 4), which could suggest that mothers might perceive excess weight, but only when in high amounts(Reference Robinson and Sutin6,Reference Parkinson, Reilly and Basterfield62) . Nevertheless, most mothers of children with obesity (78 %) and half of the mothers of children with overweight reported being concerned about their child weight, which is in line with studies reporting that parents are generally concerned about overweight and obesity in children(Reference Peyer, Welk and Bailey-Davis19,Reference Regber, Novak and Eiben22) . Findings also showed that having a child with obesity, but not overweight, was the only significant predictor of maternal concerns about child weight when other factors were taken into account. Altogether, these findings suggest that mothers may express concerns about weight at lower amount of excess weight than the amount required for them to perceive this excess weight or that mothers may avoid labelling children as having obesity given the associated stigma(Reference Pont, Puhl and Cook63).

Black immigrant mothers’ weight status was significantly associated with mothers’ perceptions of children’s weight status, such that mothers with obesity were significantly more likely to perceive their children as having overweight. The literature examining maternal weight status and perceptions of child weight status is equivocal, with some studies reporting that mothers with overweight and obesity were less likely to perceive their children as such(Reference Cullinan and Cawley64,Reference Queally, Doherty and Matvienko-Sikar65) , while others report that mothers with obesity might be more aware of their body size and therefore more sensitive to excess weight of their children(Reference Chen, Binns and Maycock66,Reference Shiely, Ng and Berkery67) . Mothers’ weight status was a significant predictor of maternal perceptions of children’s weight status only when children’s weight status was not included in the model, which suggests that children’s weight status is a more important determinant of mothers’ perceptions of child weight than mothers’ own weight status. As for concern, mothers’ weight status was not associated with their concerns about child weight, which is in contrast to several studies reporting that parents with overweight or obesity were more likely to be concerned about child weight status than normal-weight parents(Reference Peyer, Welk and Bailey-Davis19–Reference Hernandez, Reesor and Kabiri21,Reference Cachelin and Thompson30,Reference Payas, Budd and Polansky68) . It is important to note that most of these studies were conducted with White or Latino populations(Reference Peyer, Welk and Bailey-Davis19–Reference Hernandez, Reesor and Kabiri21,Reference Cachelin and Thompson30) or had a very small sample of Black/African-American parents(Reference Cachelin and Thompson30,Reference Payas, Budd and Polansky68) .

In line with previous studies, bivariate analyses also revealed that mothers who lived in food-insecure households were more likely to be concerned about their children’s weight(Reference Kral, Chittams and Moore69,Reference Berg, Tiso and Grasska70) . Several Canadian studies have shown that children living in food-insecure households, including those from newcomer families, have poorer diet quality(Reference Lane, Nisbet and Vatanparast71,Reference Mark, Lambert and O’Loughlin72) , which can contribute to the development of overweight or obesity(Reference Valera, Sohani and Rana73), thus potentially impacting mother’s concerns about their children becoming overweight in the future. Mothers who were settled immigrants were also more likely to be concerned about their children’s weight. Contrary to recent immigrants, settled immigrants could have had a higher exposition to Western media portraying thin body size/shape(Reference Natale, Uhlhorn and Lopez-Mitnik74), and thus, might be more likely to be concerned about child weight. Another possible explanation is that after immigration, some recent immigrants may face economic hardship due to lack of employment or low income(Reference Ostrovsky75), which may be of more concern to them than their children’s weight status. Mothers who had less than a university degree were also more concerned about child weight. A study conducted with African Americans showed that parents with lower education levels were less likely to be concerned about their child weight compared to parents with higher education levels(Reference Anderson, Hughes and Fisher28). Results showed that being a lone mother was also a significant predictor of maternal perceptions of overweight and concerns about child weight when children’s weight status was not taken into account in multivariate models. In Canada, lone mothers are more likely to be unemployed, to have lower education levels and to live in food-insecure households(76,Reference Tarraf, Sanou and Blanchet77) . Further, as immigrants, participating mothers might face additional challenges such as mental health issues and lower access to healthcare services(Reference Woodgate, Busolo and Crockett78). All these driving factors are related to each other as they are key dimensions of socio-economic position and constitute unfavourable social determinants of health such that mothers experiencing them may not be able to prioritise their child weight status because of competing priorities. Furthermore, these socio-economic characteristics are known to contribute to the development of childhood obesity(Reference Kumar and Kelly2,Reference Duriancik and Goff79) , which could explain why these socio-economic factors did not remain significant when implemented along with children’s weight status in multivariate models.

In the present study, children consumed about 57 % of their daily energy intake from UPP, which is similar to the UPP intake of children in Canada (57 %)(Reference Moubarac54). Such high consumption of UPP is concerning as UPP have poor nutritional value and are not optimal for children’s growth(Reference Moubarac54). When assessing the relationship between children’s diet quality, as measured with the percentage of energy intake from UPP, and mothers’ perceptions and concerns about child weight, no associations were found. There might be an indirect relationship between these variables throughout feeding practices. Indeed, perceptions and concerns have been reported to influence parental feeding practices, which in turn have an impact on children’s food intake(Reference Scaglioni, De Cosmi and Ciappolino3,Reference Entin, Kaufman-Shriqui and Naggan15,Reference Corsini, Kettler and Danthiir80,Reference Fisher and Birch81) . For example, mothers who are concerned about their children’s weight are more likely to use restrictive-feeding practices(Reference Scaglioni, De Cosmi and Ciappolino3,Reference Entin, Kaufman-Shriqui and Naggan15,Reference Corsini, Kettler and Danthiir80,Reference Skala, Chuang and Evans82) , which have been associated with a higher consumption of restricted energy-dense foods(Reference Corsini, Kettler and Danthiir80,Reference Fisher and Birch83) . Such feeding practices should be avoided given their counterproductive effects on children’s food preferences and intake, and their weight status in the long run(Reference Spill, Callahan and Shapiro9,Reference Tschann, Martinez and Penilla10,Reference Fisher and Birch81) . Therefore, studies, both quantitative and qualitative, are needed to better understand the relationships between mothers’ perceptions and concerns, their feeding practices and their children’s diet quality.

Strengths and limitations

This study has important strengths, in particular the study sample. Indeed, this is the first study to assess perceptions and concerns of child weight among Black immigrant mothers of Sub-Saharan African and Caribbean descent living in Canada, a population that is under-represented in nutrition research. Furthermore, to our knowledge, this study is the first to assess determinants of perceptions of children’s weight status per se (whether accurate or not) along with determinants of misperception of children’s weight status and therefore fills an important knowledge gap. We also assessed children’s diet quality evaluated with the degree of food processing and compared children’s UPP consumption according to Black immigrant mothers’ perceptions and concerns about child weight, which is, to our knowledge, a first in Canada and internationally. Nonetheless, the study limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings. The cross-sectional nature of this study precludes any causality inference. The sample was composed of Sub-Saharan African and Caribbean mothers living in Ottawa, some of which were lone mothers, refugees or asylum seekers, had a low income and were living in food-insecure households. Even though this sample is heterogeneous given the considerable cultural diversity of populations from Sub-Saharan Africa and the Caribbean, Black immigrant mothers from Sub-Saharan Africa and the Caribbean face similar discrimination-related challenges and health inequities in Canada(33,42,Reference Agyemang, Bhopal and Bruijnzeels84) . Due to challenges encountered during the recruitment(Reference Blanchet, Sanou and Nana39), mothers from these distinct regions were combined into one group for analysis purposes, with an emphasis on immigration status. Similar studies with larger samples of Sub-Saharan African and Caribbean mothers should be conducted to better explore possible cultural differences in the perceptions and concerns of these populations. Therefore, results from this study cannot be generalised to all Black mothers living in Canada. This study was not designed to evaluate immigrant fathers’ perceptions and concerns about child weight even though all parents/guardians’ influences, individually and collectively, contribute to maternal perceptions and concerns about child weight(Reference Remmers, van Grieken and Renders85,Reference Vollmer and Mobley86) . The sample was also relatively small, which led to extremely wide CI, especially regarding children’s weight status, and could have led to the overestimation of OR(Reference Nemes, Jonasson and Genell87). Consequently, OR should be interpreted with caution and larger studies are needed to confirm the present findings. In addition, it is important to note that only one 24-h recall per child was collected, which is not representative of children’s usual diet(Reference Ma, Olendzki and Pagoto88). The NOVA classification system only addresses food processing when evaluating diet quality. Other dimensions of diet quality, such as dietary diversity or meeting the daily nutrient requirements, should also be assessed according to mothers’ perceptions and concerns about child weight to provide a more comprehensive picture. The Figure Rating Scales used to assess mother’s perceptions of their children’s weight status might have not been culturally appropriate for this population as such tools have not yet been developed or validated for children of African descent. Future studies should aim at developing age-appropriate and sex-specific figure rating scales that are culturally appropriate for children of African descent. Studies comparing parental perceptions and concerns of various ethnocultural groups in Canada are also needed, which might help in developing obesity prevention/mitigation intervention programmes that are culturally appropriate.

Conclusion

Although several factors such as mothers’ weight status, marital status, length of time spent in Canada and household food insecurity were associated with Black immigrant mothers’ perceptions and concerns about child weight, only children’s gender and weight status predicted maternal perceptions and concerns when all factors were taken into account simultaneously. Black immigrant mothers’ perceptions and concerns about child weight, along with their immigration experience, their characteristics and those of their children and household, should be considered by nutrition professionals when developing obesity prevention/mitigation programmes as this might help increase the effectiveness of these programmes. Although mothers’ perceptions and concerns about child weight did not directly influence children’s diet quality as measured by the energy intake from UPP, it is worrisome that children from this study were consuming more than half of their daily energy intake from UPP, which can in itself increase their risk of gaining excess weight over time. Obesity prevention/mitigation programmes should focus on the food system and the social determinants of health so healthy eating and physical activity are possible and easily attainable, as these have positive health outcomes in children regardless of weight status. Further research is needed to assess the relationships between perceptions and concerns about child weight with children’s consumption of UPP. Future studies should aim at examining the long-term effect and potential mechanisms by which perceptions and concerns about the weight of Black mothers from a variety of cultural settings might influence children’s weight status, diet quality and health.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank all participants for their time and contribution to this study, as well as community partners, organisations and individuals for their support and help during the recruitment. We would also like to thank Joseph Abdulnour, biostatistician at the Institut du Savoir Montfort for his advice and guidance with statistical analyses.

Financial support:

This study was funded by the Consortium national de formation en santé – Volet Université d’Ottawa (Grant numbers 129222, 2013–2014; 131261, 2014–2015) and the Faculty of Health Sciences and University of Ottawa (Grant number 131132, 2014–2015). Cris-Carelle Kengneson was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Fonds de recherche du Québec en Santé, The Institut du Savoir Montfort – Recherche as well as the Consortium national de formation en santé – Volet Université d’Ottawa. Rosanne Blanchet was funded by a Fonds de recherche Québec-Santé scholarship and is currently funded by a Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship. Malek Batal is supported by the Canada Research Chair programme.

Conflicts of interest:

There are no conflicts of interest.

Authorship:

The study was designed by R.B., D.S., M.B. and I.G. and conducted by R.B. C.-C.K. conducted all statistical analysis and prepared the first draft of the paper, which were extensively reviewed by R.B. and I.G. M.B., D.S. and K.P.P. reviewed and contributed to the final draft. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Ethics of human subject participation:

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the University of Ottawa Research Ethics Board. Written informed consent and assent were obtained from the mothers and their children.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021004729