Introduction

In his brilliant exploration of subterranean worlds, Underland, the British nature writer Rob Macfarlane (Reference Macfarlane2019: 138) observes that “All cities are additions to a landscape that require subtraction from elsewhere”. In Paris, for example, Macfarlane descends below the limestone spires and arches to investigate the city's catacombs, where the monuments above ground are mirrored in the sprawling negative spaces left by a maze of subterranean mines and quarries. The stones used to build monuments—whether Notre Dame Cathedral or the Castillo of Chichén Itzá—must always come from somewhere else, and the negative spaces they leave behind when extracted from the ground are often neglected in our investigations of the deep history of human-environment interactions.

In this article, I reframe early monumental complexes built in the northern Maya lowlands through the negative spaces in the landscape created by the procurement of their building materials. Using the Late Formative (c. 300 BC–AD 1) and Terminal Formative (c. AD 1–250) monumental architecture of Tzacauil, Yucatán, Mexico, as a starting point, I propose that early northern Maya monumentality can be read as a materialisation of TEK, or traditional ecological knowledge. TEK refers to a cumulative body of knowledge, practices and beliefs that relate to the interactions of human communities with and within their environment, which are (re)generated in situ through historically continuous relationships between human and non-human lifeforms (Berkes Reference Berkes and Inglis1993). TEK and related concepts of Indigenous knowledge have been embraced by archaeologists as part of a larger effort to decolonise social and biological science (Colwell-Chanthaphonh & Ferguson Reference Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson2010; Atalay Reference Atalay2012).

Here, I argue that the TEK practice expressed in Tzacauil's monumental architecture is fieldstone gathering associated with the initial stages of agricultural intensification; ‘fieldstone’ is a generalised term for surface stones removed from an area of land to facilitate cultivation. I then move on to discuss monumental traditions that may similarly be entangled with fieldstone gathering, as well as other TEK practices. The parcels that Tzacauil farmers cleared of stones were intra-settlement lands—open areas between and around their residences that served as important sites for gardening and agriculture (Fisher Reference Fisher2014). In some lowland Classic (AD 250–900) Maya cities, the long-term cultivation of intra-settlement lands contributed to a pattern of low-density urban agriculture (Chase & Chase Reference Chase and Chase1998; Isendahl Reference Isendahl2012; Lucero et al. Reference Lucero, Fletcher and Coningham2015). The multigenerational harvesting of fieldstones, as a key TEK practice associated with intra-settlement cultivation, may be an important component in the origins of Maya urban agriculture.

I propose that, in places such as Tzacauil, the gathering of stones by farmers intensified during the first generations of agriculture. Concurrently, community leaders may have marshalled the accumulated fieldstone (and likely initiated the additional quarrying of stone) into novel, material expressions of political authority: the plazas and pyramids of monumental complexes. At Tzacauil and the neighbouring centre of Yaxuná, Late and Terminal Formative households also appear to have used fieldstone to construct massive residential platforms, filled with rubble and reinforced along their perimeters with lines of boulders.

Monumentality, both in public and residential architecture, arose in the Late Formative at Tzacauil, but much earlier in the Middle Formative (c. 1000–300 BC) elsewhere in the northern Maya lowlands. I suggest that interpretations of monumentality that attend to localised TEK can enhance our understanding of the diversity and tempo of both emergent monumental traditions and human-environment interactions.

Through innovative approaches to monumentality and renewed attention to the earliest periods of Maya history, archaeologists are now recognising robust connections between the origins of Maya political complexity and the engineering of the natural environment. Archaeologists have explored Maya monumental complexes as incubators for fledging social hierarchies, as mechanisms for social integration and as venues for the ritualised celebration of solar and agricultural cycles (e.g. Chase & Chase Reference Chase and Chase1995; Stanton & Freidel Reference Stanton and Freidel2003; Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Chase, Dowd and Murdock2017; Brown & Bey Reference Brown and Bey2018; Houk et al. Reference Houk, Arroyo and Powis2020).

Stones used to build Maya monuments manifest long-term interactions between communities and land. Maya monumentality can therefore be considered not just as an expression of political authority, but also as an embodiment of TEK. Recognising Maya monumentality as TEK supplements, rather than supplants, political interpretations.

As TEK is always local, when reading monumental architecture as TEK even within a single region, we should expect granular differences related to particular histories and ecologies. While here I focus on the TEK practice of fieldstone gathering as one framework for analysing monumentality in the northern lowlands, we can expect that monumental architecture across the Maya region (and elsewhere) may materialise many types of localised TEK. This article, therefore, is intended to prompt consideration of the potential TEK expressed in diverse monumental traditions and to stimulate investigation into the links between monumentality and TEK.

In the sections below, I lay a foundation for stone gathering and fieldstone mounds as elements of Maya TEK related to the preparation of land parcels for cultivation. Using ethnographic and ethnoarchaeological accounts of stone gathering, I explain why twentieth-century analogues should be adjusted when considering the scale and scope of early agricultural intensification in the northern Maya lowlands. I introduce a case study from excavations in the Late to Terminal Formative period farming village at Tzacauil, located in the central Yucatán sub-region of the northern Maya lowlands. I close by discussing the intersections of monumentality and TEK at Tzacauil and elsewhere in the Maya region.

From clearance cairns to pyramids

Far to the north of the Maya area, in New England, USA, the remains of Colonial-era agriculture remain visible in the miles of walls made of fieldstone (Allport Reference Allport2012). Settlers clear-cut forests to open so-called virgin lands for agriculture, and in doing so they revealed ground surfaces littered with stones. The settlers moved these stones to the edges of their fields, and, over time, reorganised the fieldstone into the low walls that still criss-cross the New England landscape. As well as walls, these farmers often simply left fieldstones piled in amorphous mounds known as clearance cairns; such cairns resemble those produced thousands of years earlier in Europe by Bronze Age farmers (Johnson Reference Johnson and Brück2001).

Similar patterns of fieldstone gathering, and the resulting clearance cairns, exist in the rockiest areas of the Maya region. In the northern Maya lowlands of the Yucatán Peninsula, for example, stone mounds were seeded and added to through the ongoing interactions between farmers and the karst terrain. The geology of northern Yucatán is intricate and diverse: exposed bedrock, craggy boulders, rocks, cobbles and pebbles all lend their granular textures to the land. Over thousands of years, Maya farmers have developed robust TEK for working with these materials. They learned, for example, to cultivate gardens and tree crops in large bedrock depressions, which trap soil and moisture, and even to replicate the practice in miniature by using bedrock cavities for container gardening (Kepecs & Boucher Reference Kepecs, Boucher and Fedick1996; Fedick et al. Reference Fedick2008). In order to communicate precise information about the highly variable nature of stone around them, these farmers also developed a complex lexicon (Arellano-Rodríguez et al. Reference Arellano-Rodríguez, Rodríguez-Rivera and Chi1992).

Even as Maya farmers cultivated—and continue to cultivate—rocky soils, they would sometimes opt to remove stones from a parcel of land. In the mid twentieth century, the anthropologist Ruben Reina recounted the burning of forest parcels by Maya farmers in Chiapas. After the conflagration had died down to a smoulder, stones were revealed all over the ground: “(I)t is in the midst of this charred debris that the planting will be done. Stones are removed, however, and piles of them accumulate over the years in unused areas of the fields” (Reina Reference Reina1967: 4). A similar pattern of clearance cairns has been documented in ethnoarchaeological investigations of refuse management in 1970s highland Maya communities, conducted by archaeologists Hayden and Cannon (Reference Hayden and Cannon1983: 140), who write:

(W)e sometimes came across mounds of quartz pebbles or fieldstone in the streets, some being relatively large (2–3m in diameter and 1m in height). Household owners collected these stones from their gardens and deposited them in the streets outside their compounds.

When asked about the stones, Maya household owners stated that “the pebbles tended to wear away the metal-tipped gardening tools, and sometimes even resulted in breakage” (Hayden & Cannon Reference Hayden and Cannon1983: 140). The archaeologists proposed that,

In prehistoric situations, where only more fragile and rapidly wearing wooden-tipped gardening implements were used, similar considerations may have induced many more households to attempt to keep inorganic refuse out of their garden areas either by disposal in abandoned pits, or by disposal in concentrated dumping areas. (Hayden & Cannon Reference Hayden and Cannon1983: 140)

In Yucatec Mayan, the term mul tuntah’ is used by farmers to describe the movement of stones from one place to another and it carries two related meanings: “to pile up stones” and “to mark a boundary with piles of stones” (Arellano-Rodríguez et al. Reference Arellano-Rodríguez, Rodríguez-Rivera and Chi1992; translation by the author). Archaeologists working in the Maya area have long noted the presence of stone lines and stone mounds at archaeological sites, which they have linked to agricultural field boundaries (Lemonnier & Vannière Reference Lemonnier and Vannière2013). In some pre-Contact Maya settlements, communities engaged in a practice of enclosing their house lots with stone walls as a way of protecting gardens and infield plots while affirming connections between households and intra-settlement lands (Fisher Reference Fisher2014). Many of these walls may have formed organically through the practice of mul tuntah’: farmers removing fieldstone to the edges of their house lots and eventually, like the New England farmers, reorganising the resulting clearance cairns into walls.

In settlements without stone-walled house lots, archaeological prospection has confirmed that unwalled intra-settlement lands were often used for intensive agriculture and gardening (Isendahl Reference Isendahl2012; Robin Reference Robin2012). Farmers probably cleared these lands of fieldstone, but rather than using the stone to build house lot walls, the collected rock may have been incorporated into other building projects. Attention to these ostensibly ‘vacant’ intra-settlement areas in sprawling Maya cities as important sites for farming and gardening has opened new lines of inquiry into the nature of Maya urbanism and launched ongoing investigations of Maya cities as low-density urban-agricultural settlements, akin to those found in other lowland tropical regions of the world (Lucero et al. Reference Lucero, Fletcher and Coningham2015). Fieldstone clearing may have been an important part of the origin of Maya urban agriculture.

When we project the role of fieldstone clearing back to the beginnings of agricultural sedentism in the northern Maya lowlands, however, the humble clearance cairns noted by anthropologists in twentieth-century fields and towns become inadequate analogues for the sheer scale of stone moving that would have co-occurred with the initial onset of intensification. The transition to agricultural sedentism in the Maya area took generations, and during those transformative centuries, the first waves of mul tuntah’ could have generated fieldstone mounds far larger than those gathered by a single twentieth-century household over a few years.

Considered in this way, the development of Maya monumentality can be read as an enmeshed history of emergent TEK and political complexity. I propose that some early farming communities living in stony terrains, such as parts of the northern lowlands, marshalled their growing clearance cairns—the cumulative creations of farmers’ interactions with land—into elaborate architectural complexes, both product of and venue for new forms of political leadership. Early Maya monumentality has previously been linked to the adoption of agriculture, but discussion of these linkages has focused on the marking of seasonal time rather than on the materiality of monuments as aggregations of gathered fieldstone (see, for example, discussions of E-Group complexes in Doyle Reference Doyle2012). By pulling in fieldstone from intra-settlement lands, however, early monumental complexes—as concentrations of fieldstone—would have prepared incipient cityscapes for the development of urban agriculture in later periods.

Late and Terminal Formative monumentality at Tzacauil as TEK

To explore these ideas, I present data from excavations in the northern Maya lowlands site of Tzacauil, Yucatán (Fisher Reference Fisher2019). Tzacauil is in the ejido (collective landholding) of the community of Yaxunah, whose lands also include the larger and well-studied site of Yaxuná (Stanton et al. Reference Stanton2010). Yaxuná emerged as the regional capital of central Yucatán in the Middle Formative period, a time of mobile foragers and semi-mobile forager-farmers, c. 1000–300 BC, and into the Late Formative period. During the Middle Formative, activity at Yaxuná centred on its E-Group plaza, an astronomically aligned monumental complex (Stanton Reference Stanton, Freidel, Chase, Dowd and Murdock2017). In the Late Formative, Yaxuná's political leadership commissioned the building of several acropolis groups, causeways (sacbes) and elite residential compounds. People began living in stone houses near Yaxuná's core in significant numbers at around the same time as these monumental complexes were being constructed.

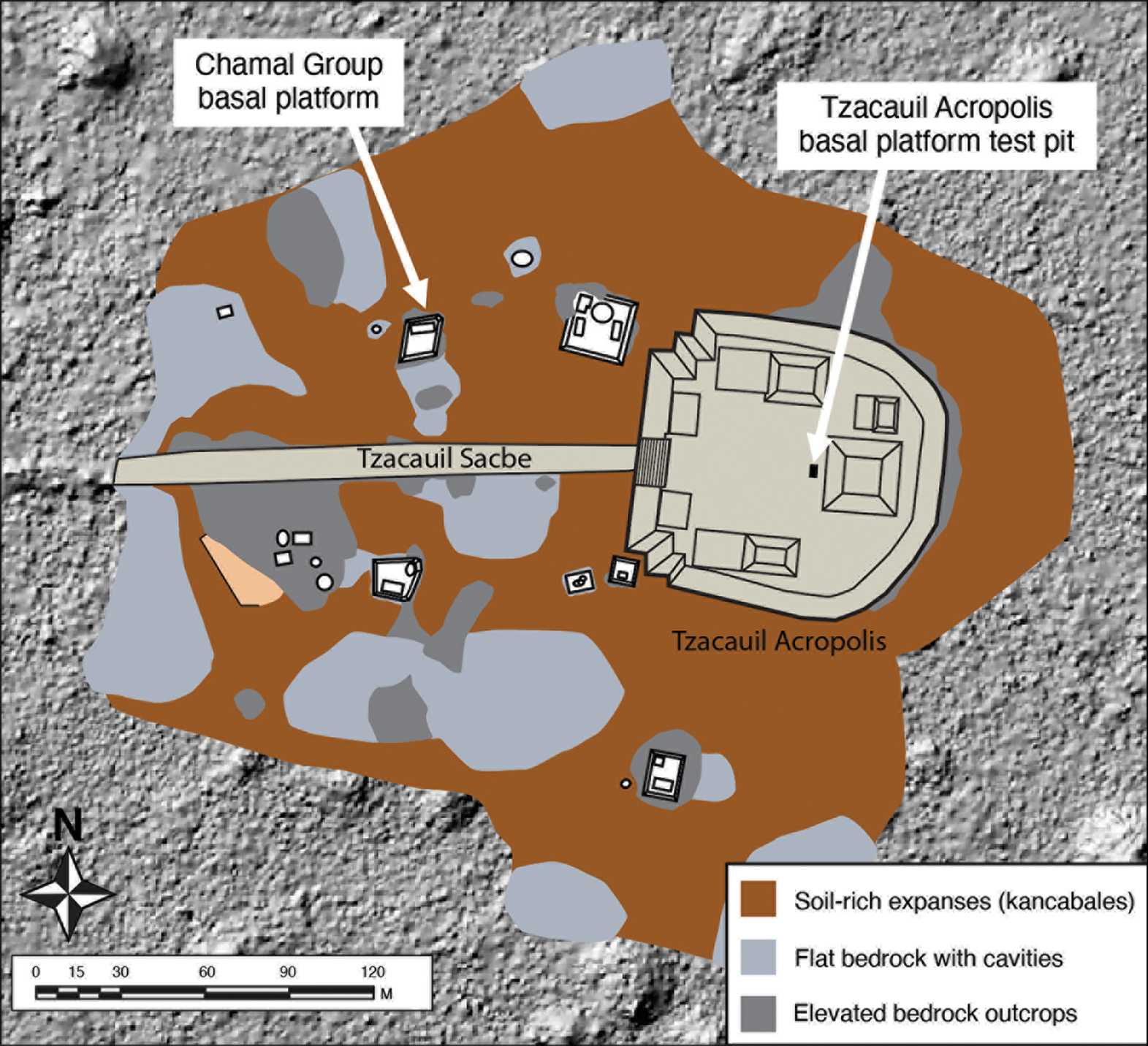

Also in the Late Formative, a small settlement was founded at Tzacauil, 3.2km east of the centre of Yaxuná. Tzacauil's Late Formative settlement replicates the same pattern found among Late Formative neighbourhoods at Yaxuná: a small number of stone houses loosely aggregated around a focal monumental complex—in this case, the Tzacauil Acropolis and its raised limestone causeway, the Tzacauil Sacbe (Figure 1). Yaxuná subsequently experienced several centuries of continuous occupation; Tzacauil, however, was abandoned at the end of the Terminal Formative, and most of its Formative house groups were never reoccupied (Fisher Reference Fisher2019). Tzacauil therefore offers insights into Late Formative household activity that is not preserved at Yaxuná. Excavations of construction fills in the platform of the Tzacauil Acropolis and in the boulder-lined basal platforms of nearby houses illustrate how Late and Terminal Formative monumental architecture potentially worked in conjunction with the TEK of fieldstone clearing.

Figure 1. Map of the Tzacauil archaeological site. This map integrates LiDAR data with findings from traditional ecological knowledge survey to depict the site's terrain of soil flats and exposed bedrock. Major monumental architectural features are indicated, as are excavations discussed in the text. Some architectural features have been redrawn and modified from mapping data originally published in Stanton et al. (Reference Stanton2008) (produced by the author).

Excavation in the Tzacauil Acropolis

The Tzacauil Acropolis is a triadic group—a Late Formative architectural form originating in the southern Maya lowlands—and closely resembles Yaxuná's Late Formative East Acropolis (Hutson et al. Reference Hutson, Magnoni and Stanton2012) (Figure 2). Comparable to other triadic groups, the Tzacauil Acropolis incorporates a C-shaped arrangement of superstructures on top of a basal platform. The basal platform measures 110 × 105m at its base, 80 × 70m at its top, and is 8m high, exemplifying the monumentality typical of the Late Formative northern Maya lowlands.

Figure 2. Yaxuná's East Acropolis after dry-season burning (photograph by the author).

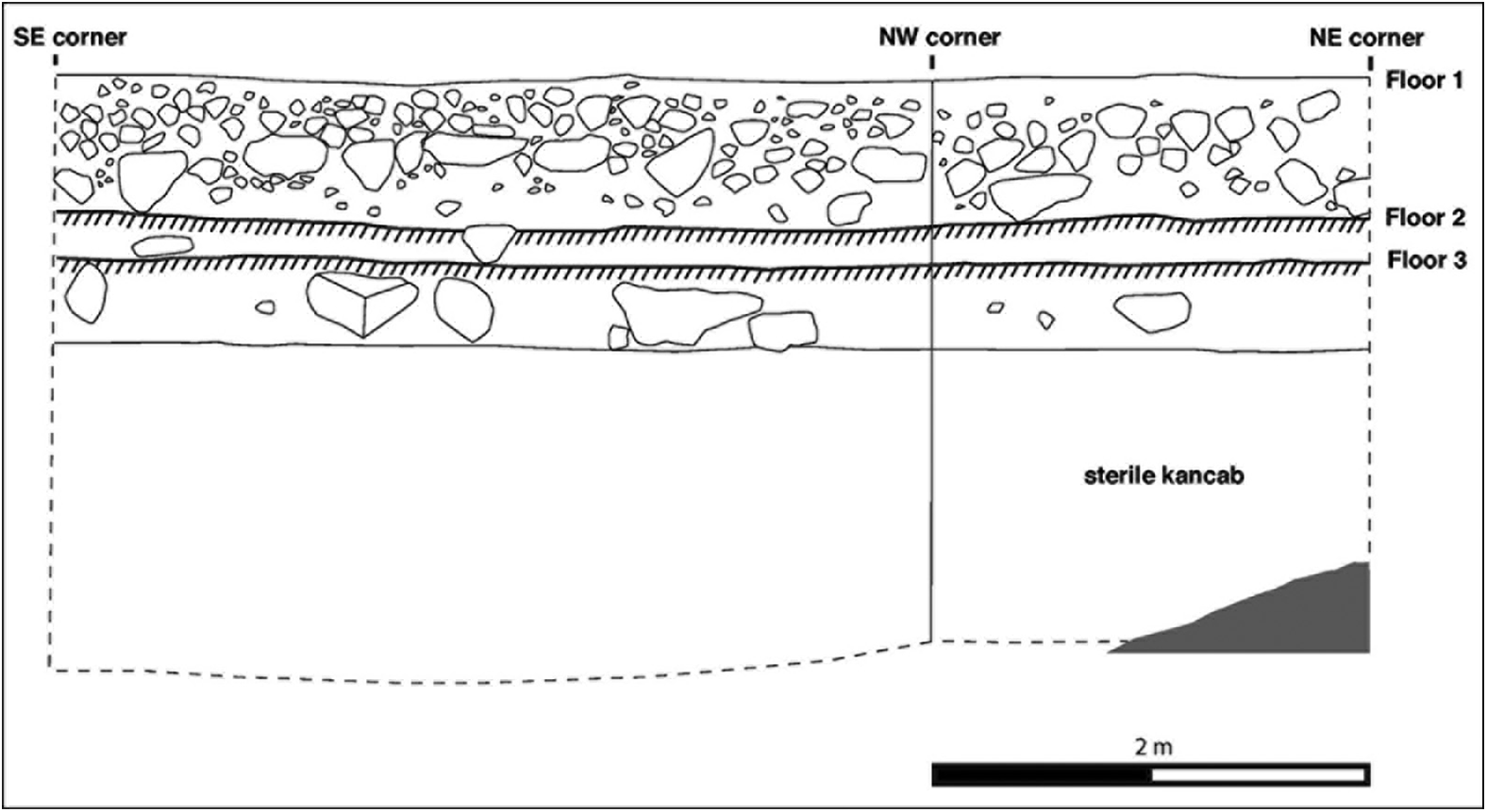

During investigations of the Tzacauil Acropolis, archaeologists and Yaxunah ejidatarios (community landowners) excavated a test pit in the basal platform to determine its construction history (Fisher Reference Fisher2019: 169–72) (Figure 3). The test pit followed procedures developed to investigate acropolis groups at Yaxuná (Stanton & Magnoni Reference Stanton and Magnoni2014) and involved digging a 4 × 2m unit into the basal platform's open plaza area, just west of the principal superstructure. The test pit excavated through three distinct construction episodes and into sterile, red soil. The red soil (kancab) in the test pit's deepest layers was compact, included no artefacts, and, in places, incorporated fragments of the underlying crumbling bedrock. We had known prior to excavation that bedrock accounted for a significant portion of the basal platform's volume, as it was visible through the collapse on the acropolis’ eastern side at a height 4m. Prior to construction, the location was dominated by a large rock outcrop, the top of which featured deep pockets of red soil.

Figure 3. Profile of test pit in the Tzacauil Acropolis (illustration by the author).

Ceramics recovered from the subfloor fill confirm that construction on the acropolis began during the Late Formative. The builders prepared the surface of the outcrop by first depositing a layer of large stones, which levelled the outcrop and raised its surface by approximately 0.60m. The large stones were in a matrix of compact, red soil mixed with sascab (limestone marl). This fill was capped with a floor (Floor 3) made of small stones, packed into a mixture of red soil and sascab and finished with a lens of fine, white sascab. The ceramics in the fill of this first construction episode include Late and Middle Formative sherds deposited along with soil collected from areas on top of the bedrock outcrop and from the surrounding ground. Given that few Late Formative sherds were included in this layer, this first episode of acropolis construction probably took place early in Tzacauil's history as a sedentary agricultural community. Sufficient refuse from Late Formative farming households had accumulated to make its way into fills associated with the first construction episode, but not sufficient to dominate the ceramic assemblage.

In the second construction episode, the builders deposited small stones on top of the earlier floor, which they capped with a packed earth floor (Floor 2). This renovation raised the surface of the basal platform by 0.20m. Ceramics in the subfloor fill included a mix of Middle, Late and Terminal Formative sherds, suggesting that the renovation occurred during the Late to Terminal Formative transition or early Terminal Formative.

Later, the inhabitants of Tzacauil renovated the acropolis again, depositing a 0.40m-thick layer of large stones on top of the most recent floor. The builders then deposited a fill of medium-sized stones, fist-sized cobbles and dark brown soil. Closer to the surface, the fill transitioned to tightly packed cobbles—ballast for a now-eroded floor (Floor 1). Altogether, this final renovation raised the surface of the basal platform by 0.65m. Projected across the acropolis as a whole, this renovation represents a massive relocation of stone from elsewhere in the landscape. Sherds recovered from this fill layer suggest—as with the previous construction episode—that this final renovation took place during the Late to Terminal Formative transition.

Investigations at the Chamal Group

The Chamal Group is one of five Late Formative residential groups at Tzacauil investigated through excavation and TEK survey (Fisher Reference Fisher2019). In Yaxuná and Tzacauil alike, Late Formative house groups consist of massive, boulder-lined platforms, built over bedrock outcrops, that support stone foundations for dwellings made of perishable materials. These platforms tend to cluster loosely around a shared focal point, such as an acropolis, with ample intra-settlement space for house lot gardening and intensive cultivation. The Chamal Group illustrates two Late and Terminal Formative settlement patterns common in both Tzacauil and Yaxuná: 1) relatively monumental, boulder-lined residential platforms, which, by size, are unmatched by the residential architecture of later periods; and 2) the tendency for Late and Terminal Formative households to settle in soil-rich areas and maintain ample open intra-settlement lands between and around residences. The Chamal Group offers a starting place for further inquiry into fieldstone gathering and Late and Terminal Formative residential monumentality.

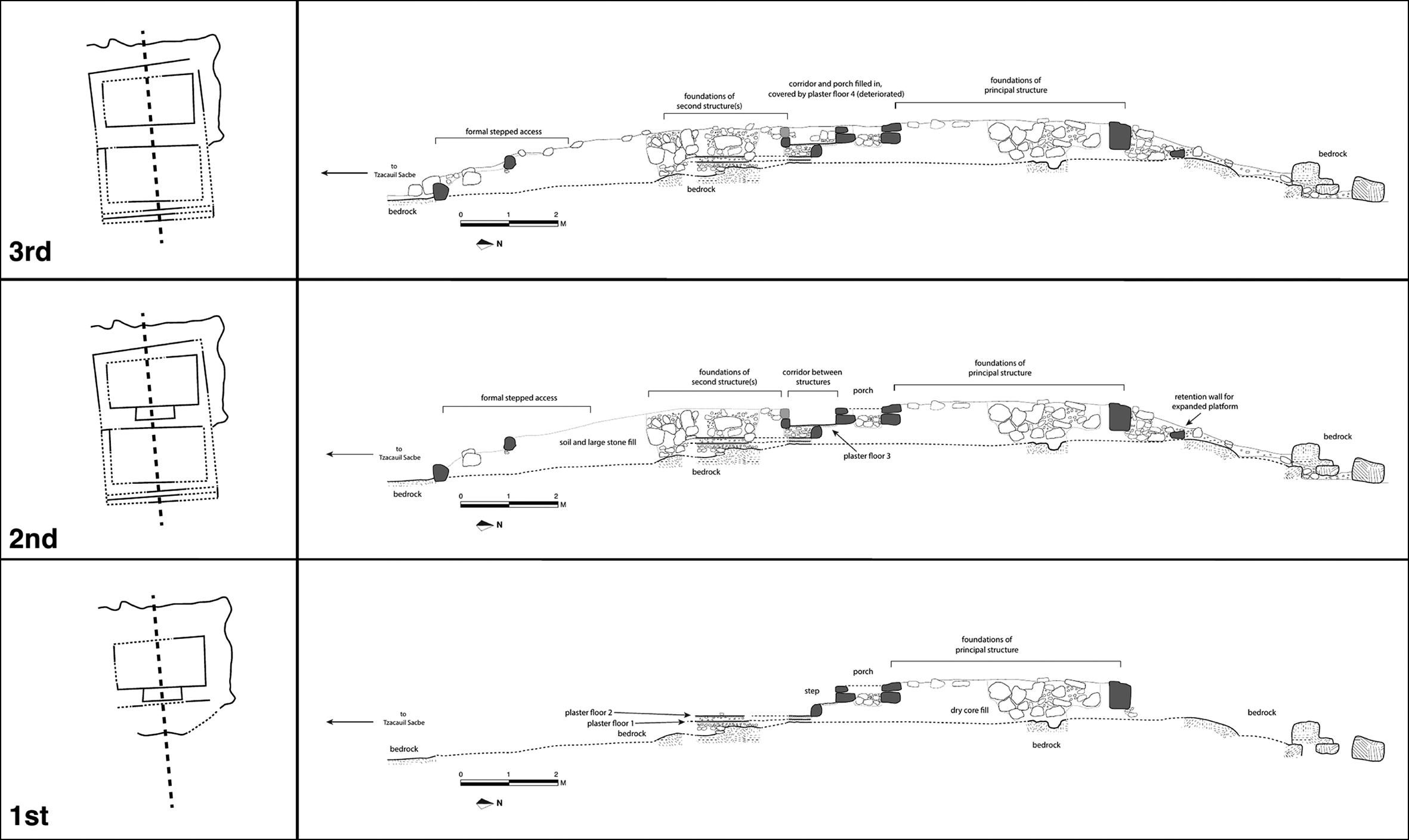

The Chamal Group is a rectangular, boulder-lined basal platform, with stone foundations for at least two superstructures. From excavations of the basal platform, archaeologists and Yaxunah ejidatarios have discerned three major episodes of construction (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Plans and profile drawings of Chamal Group construction episodes (illustration by the author).

The basal platform was built on a bedrock outcrop. The builders initially levelled the outcrop by applying soil mixed with burnt lime, before depositing a layer of large stones as dry-core fill, with no smaller fill stones or soil used to fill in the gaps between the large stones. The builders placed these large stones in a rectangular shape and built a stone wall along its southern end. They then installed a stone foundation brace for a rectangular superstructure (Structure 8A) and laid an interior floor by adding a layer of small stones, cobbles and soil on top of the dry-core fill. The builders placed slabs of limestone over gaps in the dry-core fill to prevent the floor from slumping, before capping the subfloor ballast with a tamped earth floor, which would have required periodic repair as material slipped down into the gaps in the dry-core fill.

South of Structure 8A, the builders added a floor made of gravel, sascab and soil, packed down over a layer of compact soil and cobbles over the bedrock. Of the ceramics found in these earliest contexts, a couple of sherds are of Terminal Formative date, while the rest are too eroded to identify. Given that the overall ceramic assemblage recovered from the Chamal Group includes substantial amounts of Late Formative pottery, I assign the initial construction of the complex to the Late to Terminal Formative transition.

The Group's second construction episode—an extensive renovation—dates to the Terminal Formative. A retention wall was added to the north of Structure 8A and filled in with medium-sized stones, fist-sized cobbles and soil. All the bedrock that had been left exposed to the south of Structure 8A was now buried under large stones mixed with soil. Builders added a perimeter wall of boulders around the bedrock outcrop to box in the southern side, which allowed them to expand and elevate the area of the entire basal platform. On top of this addition, the builders added a stone foundation (Structure 8B) for one or more additional superstructures, leaving a narrow passageway abutting the south side of Structure 8A (Figure 5). In the third construction episode, also in the Terminal Formative, the passageway between Structures 8A and 8B was filled with rubble and soil. This was the last substantial modification made to the basal platform before it was abandoned later in the Terminal Formative.

Figure 5. Chamal Group basal platform showing features of the second construction episode (photograph by the author).

Intra-settlement investigations were also undertaken around the Chamal Group to document traces of house lot activities. A team of archaeologists and Yaxunah ejidatarios, experienced farmers and gardeners, conducted a TEK walking survey of Tzacauil's intra-settlement lands to identify landscape features and to record on-the-ground discussions about agricultural potential (Figure 6). We also excavated trenches in intra-settlement areas to collect information about soils and past land-use practices (Figure 7). The Chamal Group shows signs of prioritising access to soil-rich areas—a pattern consistent with the rest of the Late to Terminal Formative Tzacauil settlement. Although the land to the south of the group is predominantly bedrock, and soils were visibly thin in many places, the Chamal Group maintained access to soil-rich areas to the east, north and west. These areas, classed in Maya ethnopedology as kancabales, were relatively clear of stone. Among some contemporary Maya communities, kancabales are regarded as the preferred soil type for intensive, rather than shifting, agriculture (Bautista & Zinck Reference Bautista and Zinck2010).

Figure 6. Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) survey team of Yaxunah ejidatarios and the author (photograph by D. Griffin).

Figure 7. Intra-settlement excavations north of the Chamal Group (photograph by the author).

Discussion: connecting monumentality and TEK

The transition from mobile foraging to sedentary farming in the Maya area has been described in terms of degrees (Inomata et al. Reference Inomata2020), with regions, communities and even individual households adjusting for generations their practices along a spectrum of sedentism and mobility. Likewise, monumentality emerged at different times, took different forms and followed different tempos. Monumentality in the Formative Maya world has been explored as a marker and medium of complexity (e.g. Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Chase, Dowd and Murdock2017; Brown & Bey Reference Brown and Bey2018; Houk et al. Reference Houk, Arroyo and Powis2020), and, here, I propose that emerging TEK—specifically practices such as fieldstone clearing related to early agricultural intensification—is an integral part of that history.

The practice of mul tuntah’, the Yucatec term that describes the gathering of fieldstone, incrementally produces clearance cairns during the preparations of land parcels for cultivation. Ethnographic and ethnoarchaeological accounts from twentieth-century contexts describe the resulting stone heaps as small, but these analogues are insufficient for understanding the sheer scale of the task of land clearance faced by early Maya farmers.

In contexts where fieldstone gathering arose as part of agricultural TEK, the first generations of Maya farming communities would have produced fieldstone mounds unmatched in number and size compared with those documented in twentieth-century towns. When such farmers engaged with the stoniness of the land in places such as central Yucatán in the northern lowlands, fieldstone mounds would have grown rapidly as farmers refined the TEK of localised agricultural intensification.

Emerging community leaders may have then worked to marshal these existing fieldstone mounds, as well as the quarrying of additional stone, into elaborate expressions of political power: monumental pyramids, plazas and platforms. In settlements such as Tzacauil and Yaxuná, farming households adapted fieldstone into large residences. Their houses approached monumental forms through the integration of massive, boulder-lined platforms, materialising multigenerational relationships between people and land.

We can therefore read Tzacauil's Late and Terminal Formative Acropolis and residences, such as the Chamal Group, thus. The earliest fills in both the Tzacauil Acropolis and the Chamal Group are dominated by large stones. Clearing the largest stones from lands may have been the starting point for Late Formative farmers beginning to bring Tzacauil's intra-settlement lands under intensive cultivation. The Tzacauil Acropolis then underwent a massive renovation during the Late to Terminal Formative transition, which raised the basal platform by more than half a metre. This renovation required enormous amounts of large- and medium-sized rocks, as well as fist-sized cobbles and smaller stones. Around the same time, the Chamal Group was also extended using huge quantities of boulders, medium-sized stones and fist-sized cobbles.

The volume of stones used during these Late to Terminal Formative construction events is reflected in the negative space of the intra-settlement soil expanses that were favoured by the Late and Terminal Formative households living at Tzacauil. As these areas were brought under intensive cultivation, more soil-rich areas would have been cleared of stone and fieldstone mounds would have grown larger. These stones, I contend, ended up in the monumental-scale building projects at the Tzacauil Acropolis and in the massive platform construction of Late and Terminal Formative residences such as the Chamal Group.

These patterns are not unique to Tzacauil, however: they extend to other sites in its immediate environment. Yaxuná reveals similar histories in the stone fills of its earliest monumental architecture. At Yaxuná's E-Group complex, excavations along the plaza's central axis recovered a series of superimposed floors and subfloor fills dating from the Middle Formative through to the end of the Terminal Formative (Collins Reference Collins2018). As documented in one of these excavations, the stoniest fill layer in the plaza stratigraphy is the first construction event, dating to the Late to Terminal Formative transition—the same period of extensive stone clearing documented at Tzacauil (Stanton Reference Stanton, Freidel, Chase, Dowd and Murdock2017: 464–65). This suggests that Yaxuná's farmer-residents similarly began more intensive intra-settlement cultivation—and as a result, cleared more fieldstone—in the generations leading up to a burst of monumental construction in the Late to Terminal Formative transition. Leaders may have mustered cut-stone blocks from potential quarries identified near the Yaxuná site core by LiDAR survey (T. Stanton, pers. comm.) to go along with these fieldstone fills. Similar increases in stone have been noted in Late to Terminal Formative monumental fills at other sites in central Yucatán, such as at Ucanhá (Kidder Reference Kidder2019: 152–55 & 244–49).

Given the localised nature of TEK and the plasticity of Maya monumental traditions, we would, however, be misguided to conclude that all farming communities practised fieldstone clearing, or that every stone structure resulted from mul tuntah’. Rather, different histories and different ecologies would have seeded diverse TEK practices, only some of which may be readable in monumental architecture. Below, I submit a few possible scenarios as to how localised TEK could have informed early monumental traditions, with the aim of encouraging researchers to investigate these possibilities and to propose others.

The arid plains of north-west Yucatán—an area long recognised as among the most agriculturally marginal of the northern lowlands—boasts a precocious Middle Formative monumental tradition (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Castellanos, Andrews, Brown and Bey2018; Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Bey, Gunn, Brown and Bey2018). Perhaps making up for its thin soils, the region has a high water table, and wells could have been cut into the bedrock using simple stone tools (Ringle Reference Ringle1985: 78). Thus, the Middle Formative fluency in stone expressed in the monumental complexes of north-west centres, such as Xtobo and Komchen, may have been first earned through seeking water rather than through practising intensive agriculture. Stone-cutting TEK possibly further developed when builders learned how to break down bedrock outcrops for construction materials (Ringle Reference Ringle1985: 332). Fieldstone clearing, therefore, may have played little or no role in the rise of Middle Formative monumentality in north-west Yucatán; instead, other early TEK practices associated with well-cutting could help explain the early florescence of monumental stone architecture there.

Conversely, the Puuc region of western Yucatán has some of the most fertile soils in the northern lowlands, featuring ridges, hummocks and hills interspersed with expansive, soil-rich flats, or planadas. From the Middle Formative period, Maya communities in the Puuc began modifying natural depressions into rainwater storage infrastructure—an important TEK practice, as the water table was too deep to tap (Ringle et al. Reference Ringle2021). Monumental stone architecture dating to the late Middle Formative (c. 700–450 BC) abounds in this region. Some of these monumental complexes rose in association with soil-rich areas. Reflecting on four Middle Formative acropolis groups documented in the Valle de Yaxhom and Uchbenmul, Ringle and colleagues (Reference Ringle2021: 26) suggest that the groups may have been “financed by the extensive agricultural planadas they looked upon”. Similarly, a massive Middle Formative platform identified at Xocnaceh is located along the Puuc escarpment, in a “strip of high agricultural potential” (Gallareta Negrón Reference Gallareta Negrón, Brown and Bey2018: 289).

In their LiDAR study of the Puuc, Ringle and colleagues (Reference Ringle2021) note the paucity of obvious large-scale stone quarries associated with monumental complexes. They hypothesise that stone could have been quarried from shallow pits or from rock ledges; I would add to this the possibility that the rubble cores inside these early complexes included fieldstone, potentially gathered in great quantities from the planadas by the first generations of Puuc farmers. Ring-shaped features associated with lime production have been documented within the soil-rich planadas “for reasons presently unclear” (Ringle et al. Reference Ringle2021: 32). These pit kilns, too, may be relics of fieldstone gathering from the planadas. The rich soils of the Puuc could have enabled relatively earlier experimentation with agricultural intensification, which, in turn, may have involved an earlier development for the TEK of fieldstone clearing and, by extension, monumental stone architecture.

Elsewhere in the Maya area beyond the northern lowlands, local TEK practices likely influenced early monumentality quite differently. As a single example, at Aguada Fénix in Tabasco, researchers have documented a massive artificial plateau—the oldest known Maya monumental construction. Middle Formative fills in the plateau used clay and earth, and Late to Terminal Formative fills transitioned to soil mixed with stones (Inomata et al. Reference Inomata2020: 534). While superficially this Late to Terminal Formative use of stone resembles the situation at Tzacauil and Yaxuná, the earlier Middle Formative tradition of clay-and-earth construction at Aguada Fénix suggests an entirely different history of ecological encounter among communities and land.

TEK is inherently localised and develops in situ through historical relationships between specific communities and particular places; with this in mind, the possible links between Maya monumentality and TEK discussed here is not exhaustive. Instead, this article has sought to promote discussion and further investigation among researchers of monumental traditions and human-environment interaction, in the Maya region and elsewhere. The stones and soils interred in monumental architecture encode powerful information about human-environment interaction. Continued exploration of monumentality as TEK could further illuminate deep relationships among incipient political complexity, early farming communities and the leveraging of ecological knowledge into expressions of power.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Proyecto de Interacción Política del Centro de Yucatán for supporting research at Tzacauil, especially Travis Stanton, Traci Ardren, Aline Magnoni, Scott Hutson, Gustavo Novelo Rincón, Agustín Calderón, Tanya Cariño Anaya, Harper Dine, Nelda Marengo Camacho, Ashuni Romero Butrón and César Torres Ochoa; the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia; Joyce Marcus; and the Yaxunah community. I also thank Travis Stanton and two anonymous reviewers for providing feedback on earlier drafts of this article.

Funding statement

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Award, Wenner-Gren Foundation Dissertation Fieldwork Grant, U.S. Department of Education Fulbright-Hays Program and the University of Michigan Museum of Anthropological Archaeology. Additional support was provided by the Environmental Studies Program at Washington and Lee University.