Introduction

An ageing population, driven by the decline in fertility and increased longevity due to reduced mortality and increased life expectancy, is a common demographic factor across the world. Globally, the population of those who are 60 years and above has been rapidly increasing, with future growth projected to occur primarily in developing countries, including India (World Health Organization (WHO), 2007; United Nations, 2019). By 2050, the majority of older people are expected to be living in Asia (Barber and Rosenberg, Reference Barber and Rosenberg2017). Women usually outlive men, thus by 2050 54 per cent of the world's population aged 65 and above are expected to be female (United Nations, 2019). This ‘feminisation of ageing’ has been identified as a challenge to the health-care system (Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Digiacomo and McGrath2011), since women tend to live longer than men and typically experience serious illness and suffer from co-morbidities as a consequence of living longer (Crawley, Reference Crawley2008; Byles et al., Reference Byles, Dobson, Pachana, Tooth, Loxton, Bereecki, Hockey, McLaughlin and Powers2019). At the same time, older women often encounter unique challenges including fewer financial resources to draw on than their male counterparts, plus greater possibility of living alone and dismissal of their health issues as just a by-product of the ageing process (Hurst et al., Reference Hurst, Wilson and Dickinson2013; Ní Léime et al., Reference Ní Léime, Duvvury, Callan, Walsh, Carbney and Ní Léime2015; Song and Kong, Reference Song and Kong2015). Cultural constructs of gender shape not only how society perceives and responds to a woman's health (Tuohy and Cooney, Reference Tuohy and Cooney2019) but also how older women understand their own health or illness. Gender and ageing are widely accepted as responsible for exclusion and poor access to resources (Verbrugge, Reference Verbrugge1985; Vlassoff, Reference Vlassoff1994; WHO, 2005a; Taket et al., Reference Taket, Crisp, Nevill, Lamaro, Graham and Godfrey2009), thus the feminisation of ageing means greater vulnerability for the increasing numbers of women living alone into very old age, including marginalisation of access to local health services and other existing support systems (DiGiacomo et al., Reference DiGiacomo, Lewis, Nolan, Phillips and Davidson2013).

Multiple international agreements and frameworks affirm the rights of every individual irrespective of age or gender to attain the highest possible health and access to health-care services (WHO, 1978, 2005b). However, with regard to women's health, the focus is overwhelmingly on women of reproductive age. The health needs of older women, their rights and specific requirements tend to be forgotten (WHO, 2007; Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Digiacomo and McGrath2011). For example, despite ensuring universal health coverage (UHC) as its central tenant, the WHO's 13th General Programme of Work uses outcome indicators that by definition exclude older women. Thus, measures of mortality due to non-communicable diseases (NCD) only include individuals up to the age of 70, while the indicators for intimate partner violence, decision making with regard to sexual rights and use of contraception are limited to those aged 49 years and under (WHO, 2020). Such omission has the consequence of excluding many older people, particularly women, from these metrics. The implications of this are likely to be significant since if we do not assess health outcomes of a considerable section of the population, appropriate services will not be designed or provided for them.

In India, the older population is projected to increase from the current 8 per cent to 20 per cent by the year 2050 (United Nations, 2015). The Government of India defines all those who are 60 years and above as the older population (Acharya, Reference Acharya2018). According to the last census in India, the proportion of persons aged 60 years and above was 8.6 per cent of the total population (Registrar General & Census Commissioner of India, 2011). While increased longevity in southern states of India is a primary driver of the increase in the proportion of the older population, other Indian states such as Haryana, Odisha, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab and Maharashtra are also experiencing an increase in their older populations (Alam and Karan, Reference Alam, Karan, Giridhar, Meijer, Alam, James, Sathyanarayana and Kumar2010). Among the Indian states, Kerala stands out, with the growth in the number of the older adults having increased over the past few decades (Registrar General of India, 2017). As against the national average of 8.3 per cent, 13.1 per cent of the total population in Kerala is over the age of 60 (Registrar General of India, 2017). Furthermore, among those aged 60 and above, women outnumber men and the majority of them are widows (State Planning Board, 2019). This is in contrast with other parts of India where men outnumber women among those above the age of 60 (Desai et al., Reference Desai, Dubey, Joshi, Sen, Shariff and Vanneman2010). It has been predicted that these trends will continue, thus around 20 per cent of the population in Kerala will be above the age of 60 by 2026 (State Planning Board, 2019). Four factors have driven this demographically unique nature of Kerala: the decline in fertility rates below replaceable levels, the cultural practice of men being older than women when they marry, the longer life expectancy of women over men (Desai et al., Reference Desai, Dubey, Joshi, Sen, Shariff and Vanneman2010) and the migration of the younger population as they seek better prospects outside the state (Kurian, Reference Kurian1979; Desai et al., Reference Desai, Dubey, Joshi, Sen, Shariff and Vanneman2010).

In addition to gender and ageing, the stigma of widowhood in traditional societies like India adds an additional layer of vulnerability which impacts not just on health-care access but also on other basic rights (Chen, Reference Chen1998; Dreze, Reference Dreze1990). Cultural constructs of widowhood have an impact on what is considered socially acceptable as rights for widows. Several studies have pointed to worse health outcomes associated with being an older widow in India compared to their married counterparts (Sudha et al., Reference Sudha, Suchindran, Mutran, Rajan and Sarma2006; Roy and Chaudhuri, Reference Roy and Chaudhuri2008; Sreerupa and Rajan, 2010; Basu and King, Reference Basu and King2013; Samanta et al., Reference Samanta, Chen and Vanneman2015). Previous work in India has shown that while morbidity and the resultant need for health care for older widows is high, the utilisation of health care is poor (Agrawal and Keshri, Reference Agrawal and Keshri2014; Perkins et al., Reference Perkins, Lee, James, Oh, Krishna, Heo, Lee and Subramanian2016). Even in Kerala, which is known for its matrilineal traditions, widowhood has been shown to add to vulnerability, including exclusion from health care and restrictions on social mobility (Acharya, Reference Acharya2018). Marital status has been found to be associated with both health and health-care utilisation among older adults in other settings too (Visaria, Reference Visaria2001). Thus, in the context of health-care access in India, older widows form a particularly vulnerable population. This paper has two objectives: to explore the various factors that promoted or hindered older widows’ access to health-care services in the south Indian state of Kerala and to present recommendations for both policy and practice that would result in better access to health care for older widows.

Methods

Study setting

Kottayam is one of the 14 districts of Kerala with a total population of 1,974,551 (Registrar General of India, 2001). Data from the last census estimate around 1,409,158 of the population are living in rural areas and around 140,397 in urban centres (Agrawal and Keshri, Reference Agrawal and Keshri2014). Kottayam is sub-divided into five taluks Footnote 1 and 100 villages (District Administration Kottayam, 2020a). Provision of health care in India follows a mixed model with both public and private health-care providers existing side by side. The public health system follows a hierarchical structure of facilities that are based on population norms and starts with sub-centres that are the most peripheral health-care facilities followed by the Primary Health Centres (PHCs), Community Health Centres (CHCs), sub-district hospitals and district hospitals (Chokshi et al., Reference Chokshi, Patil, Khanna, Neogi, Sharma, Paul and Zodpey2016). At the top of this hierarchical structure are government medical colleges. The private health-care system consists of a wide variety of health-care facilities starting from standalone clinics managed by an individual medical professional right up to super-speciality hospitals. The public health system in Kottayam consists of 55 PHCs, 20 CHCs, three sub-district hospitals, four district hospitals and a Government Medical College (District Administration Kottayam, 2020b). Each PHC has sub-centres under its jurisdiction as per the population norms.Footnote 2 In addition to public health facilities, the private health-care system comprises 13 hospitals providing facilities ranging from primary to super-specialist care as well as numerous individual clinics. According to the latest report by the state government, 15.9 per cent of the total population of Kottayam is above the age of 60 (State Planning Board, 2019).

Data collection

Ethnographic fieldwork was conducted between November 2018 and January 2019 and again between October 2019 and January 2020 in Kerala by the first author (MSG) who is fluent in the native language of the participants (Malayalam) and has prior experience working with marginalised communities. Prior to commencing data collection, MSG visited the health facilities in areas where there were a greater number of widows above 60 years who were living alone. During these visits, discussions were held with the medical officer of the health facility as well as the community health workers at the facility who are known as accredited social health activists (ASHAs). The purpose of the study was explained, along with details of what participation would involve for widows, health-care workers and key informants. The specific areas and details of widows who were living alone and the ASHA working in that area were also noted. During the first visit to the community, MSG was accompanied by the area ASHA. During this visit, initial contact was made with potential participants, the purpose of the study was explained, willingness to participate was ascertained, and a tentative time and date for a second visit for data collection was fixed. Any questions raised by potential participants were answered and contact details were obtained. In some instances, the initial visit was also utilised to introduce the researcher to the local representative of the area and explain the study and its purpose. This was deemed necessary, especially in rural areas, as communities were wary about outsiders visiting women who were living alone. This approach enabled participants to become familiar with the researcher, built rapport, and enabled a frank exploration of issues related to their health and health-care access.

In-depth interviews (IDIs) with the widows took place at their homes whereas IDIs and focus group discussions (FGDs) with health-care workers and key informants took place at their office, after their work hours or at their homes depending on their preference. One of the key informant interviews was conducted over the telephone. Participant observation (PO) involved being present at the PHCs and CHCs in their common areas during the designated day when the older men and women in the area were asked to come for check-ups and collect their medication, and accompanying the mobile neighbourhood clinic (vayomitram) team (Kerala Social Security Mission, 2018) in Vaikom taluk during their visits to the different wards. This enabled both observation and interaction with older men and women who visited the clinic as well as health-care providers who were present. The first author also carried out PO at Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee SchemeFootnote 3 (MNREGA) allotted worksites and observed the inclusion of older widows into communal work that was implemented.

Sampling

Widows over the age of 60 and living alone were identified using a two-stage process. In the first stage, with the help of the National Health Mission office in Kottayam, widows who fitted the study criteria were identified using the line-listFootnote 4 maintained by ASHAs. Based on this list, areas where there were widows who fulfilled the criteria were shortlisted. This process enabled the identification of Kottayam and Vaikom towns as the urban centres and Manarcaud Parampuzha, Kumarakom and Ayarkunnam as the rural areas for fieldwork. Kottayam and Vaikom were served by secondary-care government hospitals, whereas the rural villages were served either by CHCs (Kumarakom and Ayarkunnam) or a PHC (Manarcaud and Parampuzha). In the second stage, theoretical sampling (Urquhart, Reference Urquhart2013) was undertaken, with initial interviews providing new topics that were explored in subsequent interviews. The interview guide and our initial conceptual understanding of the different dimensions of access guided by the theoretical framework of Levesque et al. (Reference Levesque, Harris and Russell2013) were used only as departure points to listen to our participants and think analytically about the data that emerged (Table 1).

Table 1. Initial list of themes explored in the interviews and focus group discussions

As the data collection and analysis occurred concurrently, the topic guide was revised to accommodate new categories that emerged from the initial interviews and analysis (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2014). For example, initial interviews with widows pointed to social networks, the availability of MNREGA work, non-kin support and mental health as key issues. These were explored in detail and also guided the selection of further participants. Following data collection with the widows, FGDs were conducted with ASHAs of each health facility under whose jurisdiction data were collected. All ASHAs who provided health care for widows fulfilling the study criteria were invited to participate. IDIs were held with both medical officers and ASHAs of the health facilities in order to explore in depth some of the issues that had come up during fieldwork.

Twenty-one IDIs were carried out with widows in both urban and rural areas of Kottayam. Eight IDIs and four FGDs were conducted with local health-care providers. Three key informants, including academics and a domain expert on health care for older men and women in south India, were also interviewed (Table 2). Data collection continued until saturation of themes was reached. Seven instances of POs were conducted at the different health facilities, the mobile neighbourhood clinics and at a MNREGA work site. Detailed field notes were recorded and integrated into the analysis.

Table 2. Participants and data collection methods

Notes: IDIs: in-depth interviews. FGDs: focus group discussions. MNREGA: Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme.

Data analysis

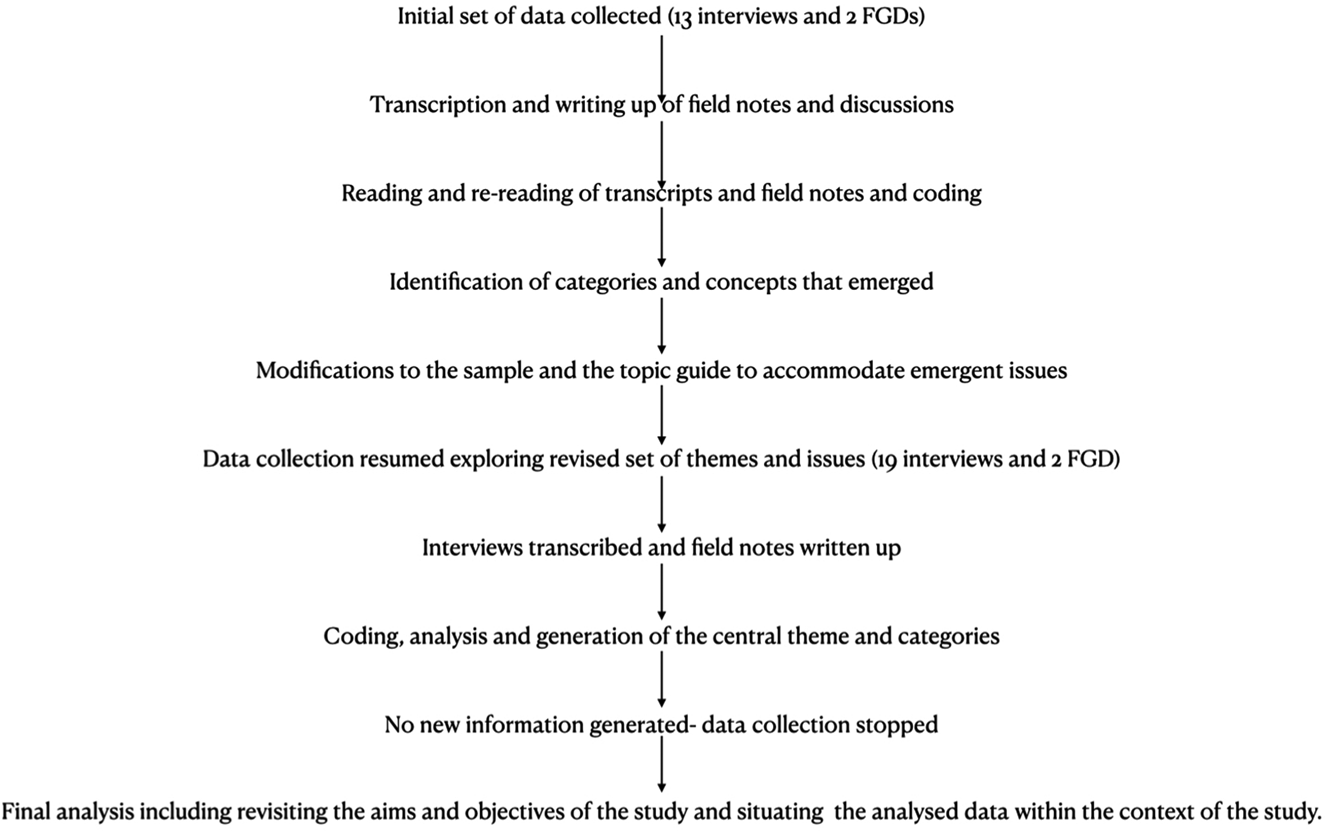

With the consent of participants, interviews and FGDs were audio-recorded, transcribed and translated into English, and cross-checked with the original recordings in Malayalam. The translated transcripts were coded using an inductive approach to allow codes and categories to emerge from the data. This involved allowing codes and categories to emerge from the data rather than imposing any external theoretical frameworks on to the data during this process. In the first step open coding was carried out on the initial set of transcripts and field notes, and this led to the emergence of initial themes and categories. Insights received were used to make additions to the interview guide before further interviews were carried out. This process of constant comparison of the data and the various categories that emerged was carried out until no new information was arising out of the interviews (Figure 1). A second author (PU) independently coded a sub-sample of transcripts and the two sets of codes and categories were compared. Any discrepancies in the coding were reviewed through in-depth discussion and negotiated consensus. A high level of agreement between coders was noted. Coding of transcripts was carried out using the software package Atlasti.ti 8.4.2.

Figure 1. Sampling and analysis process.

Note: FGD: focus group discussion.

Establishing rigour and credibility

Different strategies were used to establish that our findings were credible and reflected the lived reality of our participants. First, we used, member checking (Guba and Lincoln, Reference Guba, Lincoln, Denzin and Lincoln1994; Forbat and Henderson, Reference Forbat and Henderson2005; Harvey, Reference Harvey2015), sharing overall findings from the initial analysis with participants and recording their feedback in detailed field notes to validate our findings. These observations were integrated into the findings presented in this paper. Key informants were also emailed a copy of their transcript with the option to discuss both their interview and the overall findings at a mutually agreed time. Secondly, data source triangulation (Patton, Reference Patton1999) involving the comparison of perspectives of different stakeholders and methodological triangulation (comparing the data that emerged from IDIs, FGDs and POs) were used to enhance the quality of the analyses. Finally, negative case analysis was used to account for outliers in the narrative, helping us to understand why some of our participants had experiences that were contrary to the narrative espoused by others and thus improve the credibility of the findings (Lincoln and Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985). For example, initial interviews pointed to the general idea that financial status was an enabler of access to health care. However, one participant who was economically independent and lived in her own house pointed out that in spite of financial independence she had very poor social networks and did not find it easy to access health-care services. Exploring the reasons discussed by this outlier led to the discovery that financial independence was not always conducive to building social networks and older widows who had relocated to a new neighbourhood and lived by themselves in particular faced barriers to building their social networks and accessing health-care services in spite of being financially independent.

Ethics approvals

Informed consent was gained from individual participants prior to data collection. The Human Research Ethics Committees of the University of Canberra and the Indian Institute of Public Health Delhi provided ethical approval. Regulatory permissions were obtained from the Kerala Department of Health as well as the National Health Mission office at Kottayam.

Results

Widows who took part in this study were from both urban and rural locations in Kottayam district. Their ages ranged from 60 to 77 years, with widowhood duration of 4 months to 37 years. Some widows were in the Above the Poverty Line category (APL) whilst others were categorised as Below the Poverty Line (BPL). APL and BPL are classifications used by all official programmes in India and denote those who are above and below the nationally designated poverty threshold. Common health conditions reported by our participants included hypertension, diabetes, cardio-vascular diseases, osteoporosis, cancer, hearing impairment, poor eyesight as well as age-related conditions including increased frailty and limited mobility. With the exception of two of our participants, the widows, whether belonging to the APL or BPL categories, lived in their own houses. Among the widows who belonged to the APL category, the primary sources of financial support were support from their kin networks, including children, and various government and private pension schemes. Among widows belonging to the BPL category, the primary sources were the widow pension scheme of the state government as well as participation in MNREGA-related work in their area. We present some of the key themes and categories (Table 3) that emerged across this varied set of participants and discuss the perspectives of the different stakeholders under each theme.

Table 3. Key findings that emerged from different participants

Notes: NCD: non-communicable disease. PHC: Primary Health Centre.

Altered family structure

A universal theme that emerged among our participants was how the broader social understanding of what constituted a family unit and the responsibility to care for the old had undergone a fundamental change over time. These included change in living arrangements, from extended family units comprising individuals across generations living in the same house to smaller units that did not necessarily stay together, the migration of the young out of Kerala in search of better jobs and the overall reduction of family size. Widows pointed out how they had taken care of their parents in their old age but were now alone as their children had left Kerala or even India. Many participants described how in previous generations large families were the norm and one child would take up the responsibility of caring for their parents in their old age. However, with the societal shift to smaller families, this tradition of taking on the responsibility for the care of the older members in the family had changed. Yet another change that has come with the transformation of the family unit has been the absence of grandchildren from the daily lives of the older members:

I took care of my mother-in-law. In those days we had to do that. We lived in the same house, so it was easy to do that. Nowadays who lives with their older generation? All that has changed a lot. (IDI, widow, rural, WR 3)

I have a son and a daughter both are not in Kerala so I can't expect them to take care of me. I am alone since the death of my husband. (IDI, widow, urban, WU 2)

Doctors and other key informants who spoke about this also acknowledged that this was the reality and migration would continue in future. The need to reorient services to align with this new reality was recognised:

See this trend is not going to change. It is the case now and it is actually going to increase in the future. Ironically, it is the older men and women who are alone who worked hard to ensure that their children got a good education and jobs. But as a result, they are now alone. (IDI, medical officer, MO 3)

So, the future is looking bad because earlier people died earlier. The life expectancy of Kerala was only 50 years in 1945. So average life was very low, and you had more children. Now life is high, you have lesser children [sic]. (IDI, key informant, KI 2)

All key informants pointed out that migration has always been a feature of Kerala society, but a more pertinent explanation for the current vulnerability of the older population in Kerala was associated with smaller families becoming the norm:

Migration was always a feature of Kerala society. There used to be more children per family and then one of the children would get the responsibility of taking care of the parents and they would be compensated in some way with more land that is given to them and all of that. But that system has almost crumbled with two children and sometimes one child per family. (IDI, key informant, KI 2)

Loneliness

Loneliness and an overall lack of meaning was mentioned by the majority of the widows. The altered family structure coupled with migration of the young meant that most older widows lived by themselves and did not have caring responsibilities for their grandchildren as in the past. This shift is a recent development in Kerala society and deprived older widows of both the presence of family members within their home and caring responsibilities that gave them a new sense of purpose. Those who reported feeling lonely also discussed their lack of motivation to seek health-care services until their condition deteriorated to the point of them being unable to manage activities of daily living. Among widows who reported loneliness, belief in God was a source of comfort and this was reported across religious affiliations of our participants:

For the past 30 years, I have been living alone here. I do not have anyone, and I am weak due to my age. When I think of it, I feel sad. I have nobody to even accompany me to a hospital. (IDI, widow, urban, WU 1)

I have been here for four years. I have nobody to talk with. I watch TV for some time, but after seeing it for some time I get bored. Then I sit here by doing nothing. If we do anything, even lightly then we get mental happiness. How can we watch TV for all time? (IDI, widow, rural, WR 6)

Doctors who were interviewed spoke about the sense of loneliness and being left behind as widely prevalent among the older population. However, they discussed what was essentially a result of multiple social changes including family structures that changed, caring responsibilities that were altered, etc., from a medical perspective that required clinical interventions to be addressed. While there was an overall acknowledgement of this issue, there were no serious efforts to address even the issue of depression from a clinical perspective and provide mental health services. Most health-care services for older adults in Kerala focused either on chronic disease management or palliative care. Services for individuals with health conditions that did not fit into these two broad categories (such as mental illness, for example) were lacking:

Depression is the main problem for most of them. That itself is the reason for enhancing the severity of their illnesses. If we can tackle it while they come to us … they actually come to talk with us for five minutes. (IDI, medical officer, MO 1)

Mental health is completely neglected. There is something known on paper known as a district mental health programme. I don't think anything is happening with that. I don't think there is a sensitivity towards the fact that you know the older population has mental health needs and it needs to be delivered in a sensitive manner to them. (IDI, key informant, KI 1)

Among our sample, a small section of the widows did not report loneliness as an issue. A common feature of this sub-group was participation in social activities. For example, one of the widows living in an urban area spoke about how she took an active part in her church committees. This ensured that she was able to contribute to others and also forget about living alone without her children. Another widow spoke of how her neighbours kept her busy and enquired about her. One of her key daily activities was watching her neighbour's grandchild play in her courtyard when she returned from school:

No, I won't say that I am lonely. The reason is that I keep myself busy with activities at my church and I also take tuitions. I am not sitting at home all the time and there is a big difference. If you come across widows in your work who are lonely or sad, ask them about their activities. I feel it is only those who are not engaged in any activity who are depressed and feeling lonely. (IDI, widow, urban, WU 6)

Maintaining independence

Several of the widows in our sample expressed a strong desire to be independent. To them living in their own homes as opposed to institutional care homes, even if this meant that they had challenges when it came to accessing health care, gave them more power and control over their lives which was important for them. Even those who suffered from limited mobility preferred to remain living in their own home. This was in contrast to the understanding expressed by some of the health system stakeholders that institutional care might be a valuable option for those living alone, especially if they were suffering from conditions that restricted their mobility or required constant care. One of the widows whose mobility was highly restricted stated that she preferred to live out the remaining time in her own home which was associated with a lot of memories for her. However, at the same time there was an acknowledgement that if she became bedridden for any reason, she would have to shift to a care home for older adults as it would be impractical to continue living alone.

Linked to this need for independence was the desire not to be a burden to others, including children, relatives or neighbours. Referrals and inpatient health care required someone to accompany the person receiving the treatment; many of our participants postponed seeking care until their symptoms were no longer bearable to avoid having to impose this on others. While exploring this further, some of the widows explained that at their age enduring pain and discomfort was a part and parcel of life. Doing so was seen as the right thing to do, rather than constantly disturbing others for help to access health-care services:

My daughters are living with their family in another place. Even though they have a job they have their own difficulties. So, I am not ready to make them worry about me also. (IDI, widow, rural, WR 9)

No, I do not go at the start. I go when I feel that it is intolerable. (IDI, widow, rural, WR 4)

Social networks

Among our participants, two types of networks emerged that were important when it came to their health and access to health care. These were kin networks comprising immediate family such as children, grandchildren or relatives who lived nearby and non-kin networks that consisted of neighbours and larger social groups to which a widow was connected. These groups included membership of a religious congregation, social gatherings in the neighbourhood, as well as MNREGA work settings and neighbourhood clinics. A common feature noted was how participants formed a ‘personal community’ that included kin and non-kin relationships depending on their particular circumstances, preferences and values. It was this ‘personal community’ that the widows depended on when in need. The quality of relationships that a widow had with those who were part of this sub-group strongly predicted their ability to access multiple resources including health care. For example, several of the widows in our sample did not have any strong kin networks, but they were able to access health care when required due to their strong non-kin networks:

I cannot go out alone in my condition, so my neighbour he will call an auto and take me and then bring me back here. He even used to get me my rations from the store till they started the new rule of verifying my thumb impression.

(IDI, widows rural, WR 5)

In fact, the quality and presence of strong social networks were mentioned by different stakeholders as key factors that promoted health and wellbeing, in general, and access to resources, in particular:

It is not financial status when you talk of the situation of widows living alone, it is mainly the relationships they have with their neighbours and others that matter. We have seen many widows who are well to do but they are lonely and depressed and if something happens to them no one will even come to know in time. (FGD, community health workers, FGD 2)

Social networks played a positive role with regard to health and wellbeing in two prominent ways. First of all, those in our sample who had good kin or non-kin relationships spoke more about their motivation to remain healthy and were less likely to refer repeatedly to loneliness during the interviews. Secondly, the presence of strong social networks enabled greater access to resources including health care. With regards to health care, this included aiding physical access to health facilities and doctors by facilitating transport and accompanying a widow to the health facility. There was also a sense of solidarity among the community when it came to support for older widows in their locality. For example, during fieldwork in certain areas, it was observed that shopkeepers allowed widows, who were very poor and solely dependent on widow pension or other government support, to obtain provisions from their stores and run up debts until they received the pension payment. Yet another instance was how local representatives allowed women who were older and unable to do much physical work to register for MNREGA work while looking the other way when these women were unable to contribute. When this was explored, the local representative explained that the circumstances of some of the women was really difficult and so the community was ensuring that they were able to get some monetary support. Some of our participants also pointed out how ASHAs who visited them helped them to identify relevant government schemes, informed them about amenities that were available for them at the local health facility and enrolled them into government schemes designed to support the older population. Yet another important aspect that was highlighted was how the home visit by the ASHA provided an opportunity to talk about their problems. ASHAs in many areas were therefore an important part of the community networks for some of our participants:

One ASHA came here to see me. She asked me whether I need a walker. I said no. But I am so happy that she asked me so. (IDI, widow, rural, WR 8)

We also observed that in certain instances, solidarity amongst widows trumped considerations of caste or religion:

The person you met on the way to my house, she is a nair woman while I am an ezhava. Till my house was built by the government recently, I used to go and sleep at her place. We have so many things in common. Our caste did not matter at all. Even now we are good friends. (IDI, widow, rural, WR 11)

Many of the ASHAs, as well as our key informants, noted that widows who were financially well off were less able to depend on social networks compared to those who were poor. One key informant who had several years of experience working among the older population in Kerala explained that poor families tended to depend more on their local community and hence a strong set of non-kin networks was already in place by the time a person reached 60 years of age. Thus, being financially poor was in this situation not necessarily a negative feature, since it was a potential enabler of social networks:

Women in the BPL category living alone have the possibility of having more social networks. They depend more on others in the community. They need networks far more, support far more. Because by being BPL itself they are socially dependent. So, they have more links and communication with many people. In a place if the houses are small and situated nearby then there is greater chance of interaction between the neighbours; mutual support comes automatically. (IDI, key informant, KI 1)

However, the ability to build and nurture new social networks diminishes with age. In our sample, we had three widows who had recently moved to their present localities and found it difficult to integrate with their local community. They chose to depend on their kin networks even if these were located far away. The mutually trusting and supportive relationships with the local community observed for other widows was absent for these three widows. Widows might also lack these social networks if they were stigmatised and excluded from the community for various reasons, including mental illness or being ‘tainted’ as immoral:

At the same time for those who have been excluded from the community because of any reason may get opposition from the society. For example, if a widow is classified as a ‘bad woman’ by her community then it becomes very difficult. They will exclude her and not support her. (IDI, key informant, KI 1)

Challenges of urban living

During fieldwork, it was observed that reaching widows with services and enrolling them in various government schemes was comparatively easier in rural areas compared to the urban centre in Kottayam. Kerala has an established tradition of local self-governance through the panchayat raj system in the rural areas. The panchayat raj is a system of local self-governance that is prevalent in India and is the lowest tier of governance in rural areas. Due to their nature of being decentralised, panchayats were more aware of the number of older adults living in the areas under their jurisdiction and this enabled ASHAs and other community workers to reach out to the widows in an efficient manner. The situation was very different in urban centres where the older adults preferred not to interact much with the public health system or other civic officials. ASHAs in urban centres also found it challenging to reach the older population, especially those who were financially well off and lived in apartments. This was partly due to the socially isolated nature of these living conditions and the minimal interaction with the local community:

At least in the rural area we have a system in place and people know their neighbours. In urban centres we have a problem in reaching those in need of us. Add to this those who are living in apartments where they do not know who is living next to them. We also do not have the data that we have in the rural areas on the elderly population. (IDI, key informant, KI I)

One of the main issues in the urban areas is reaching the older population, only if our ASHA is able to reach those in need can we offer services right? Even physically getting access to these buildings for our ASHAs is difficult due to the security measures that are usually common at these apartments. (IDI, medical officer, MO 2)

During fieldwork we also realised that in some cases neighbours were not very aware of older adults who lived by themselves in some of these apartments. Additionally, some of the ASHAs reported how it was challenging to visit those living in urban areas when compared to those living in the villages as physical access to an urban apartment was restricted due to various security features that were in place in most apartments. Key informants and health-care workers described this as a difficult situation. Reaching widows who did not have adequate support systems was tougher for the public health system than providing services in rural areas.

Some of the urban participants described how their primary support system centred around personal kin networks, preferring not to interact with others from the local community. While it is possible that some of these widows had strong kin networks that provided support, it also highlighted the challenges a widow without strong kin networks living in an urban centre could face when the need arose to access health care. One of our key informants spoke of how several factors made it challenging for the public health system to reach out to older widows in urban areas. They included a general trend of relying on private health-care providers among the rich, as well as the tendency to rely on their own self and immediate family rather than the community for their needs, which was reinforced by the individualistic nature of urban living.

Neighbourhood clinics that enabled access

Vayomitram neighbourhood clinics emerged as an important facilitator of access to health care, particularly in urban areas. These mobile clinics visited localities where a large number of older people above the age of 65 were living and provided preventive and curative primary care. Clinics functioned out of government day-care centres (anganwadis) and other schools in the area. Older people from both APL and BPL populations made use of these clinics in order to get primary care and treatment for their chronic conditions. What stood out was how these clinics transformed from providing health care to enabling strong social networks among the attendees. While participants mentioned the advantages of decentralised care, what motivated them to attend was the fact that the neighbourhood clinics went beyond merely providing health-care services. Participants recalled celebrating birthdays and festivals at the clinics and also discussed how the staff engaged with them outside diagnosis and prognosis of their health conditions:

We celebrate all major festivals and even birthdays sometimes at the clinic. It is more like a club of old people than a clinic. (IDI, widow, urban, WU 10)

This approach to providing health care for older populations was not observed in rural areas where most of the care was delivered at the PHC level during the weekly ‘NCD clinics’. As a result, older men and women with any NCD conditions gathered at the PHC on this day, resulting in long queues. Doctors described this as counterproductive, since it meant that the quality of care suffered in the process:

You saw the queues right; it is not easy to provide good quality care for everyone when you have such long queues. Every one of them expects me to talk to them for at least five minutes and if I don't engage them in conversation then they are not happy. (IDI, medical officer, MO 2)

Limitations of health insurance

With the exception of two of the widows, our participants were covered under either public or private health insurance schemes. Most of those who were BPL were covered by government insurance schemes whereas those who were APL had subscribed to private insurance. Except for one of our participants, who made use of insurance for inpatient cancer treatment, none of the participants had made use of the insurance schemes. It was illuminating that of the two who did not have any insurance, one widow had let her government health insurance lapse. She explained that being covered by health insurance did not address her common health-care expenses and hence she did not find any reason to renew it even though it was provided to her for free! When this issue was explored with other participants, they concurred that for most of their health-care expenditure (which required outpatient primary care), their health insurance provided no cover:

I had it for two years and after that I did not renew it and I will not renew it. What is the use of having this card in my bag when I am spending from my pocket to buy my medicines? (IDI, widow, rural, WR 5)

I have government health insurance. They told to take it and I took it. It was very useful when I had to get chemotherapy for cancer. (IDI, widow, rural, WR 9)

Discussion

The ageing of the global population has significant implications, especially for health and social policy and services. Ensuring access to health care for older populations is a key component that will determine whether or not UHC and the Sustainable Development Goals are achieved (Barber and Rosenberg, Reference Barber and Rosenberg2017). Among the older population, widows living alone are a highly vulnerable group and previous work in the Indian context has shown that while morbidity patterns and the requirement for health care are high among older widows, the utilisation of health-care services by them is poor (Chen and Dreze, Reference Chen and Dreze1992; Agrawal and Keshri, Reference Agrawal and Keshri2014; Perkins et al., Reference Perkins, Lee, James, Oh, Krishna, Heo, Lee and Subramanian2016). Age, location, education and various socio-economic factors have been shown to have an impact on access to health care for older widows in India (Agrawal and Keshri, Reference Agrawal and Keshri2014). Our work, while acknowledging that such factors might have implications for health and access to services, shows that social networks and the social capital that they confer play a significant role in promoting both wellbeing and better access to health care. These networks were present at three levels: family, neighbourhood and the wider community. Participants formed a ‘personal community’ drawn from these three levels but characterised more by non-kin relationships. The quality of relationships in these ‘personal communities’ was far more important in promoting access to health care than other socio-economic factors. Connections with neighbours and local communities have been shown to be very important in promoting wellbeing among older women (Tuohy and Cooney, Reference Tuohy and Cooney2019). We found this to be true in our study as well. Strong social networks also addressed the loneliness that was common among the widows. Social support and having a sense of belonging to a common group has also been shown to improve healing and overall wellbeing in certain chronic conditions for the old (Upton et al., Reference Upton, Upton and Alexander2015). However, variability in forming these networks was observed. Those who had settled in a neighbourhood in their twilight years, individuals stigmatised by their local community and economically well-to-do older widows living in urban towns were less likely to form strong personal communities in their neighbourhood.

Economic status is universally considered an important predictor of vulnerability. However, our study shows how poor older widows were able to develop strong social networks when compared with those who were financially well off. One reason for this included a history of dependence on the local community that enabled more communication and interconnectedness. This is an important issue that needs to be taken into account when government initiatives seek to provide services for the older population, especially in health care.

The role of the family as a key source of support and interdependence for older people has been demonstrated by several studies (Desai et al., Reference Desai, Dubey, Joshi, Sen, Shariff and Vanneman2010; Brijnath, Reference Brijnath2012; Navaneetham and Dharmalingam, Reference Navaneetham and Dharmalingam2012). However, we found that declining fertility and high levels of migration by the younger population had changed the role of the family in the care and support for older adults in Kerala. This had an impact not only on sources of support for elderly people, but also changed the reciprocal relationships that existed between older adults and the young in extended families in the past. Older adults were denied opportunities to be involved with their grandchildren, depriving them of relationships that have been shown to be an important component of productive ageing in India (Visaria and Dommaraju, Reference Visaria and Dommaraju2019). Widows who participated in our study referred to this development with a sense of loss and inevitability.

One of our findings was the significant role played by neighbourhood clinics in improving access to health care and building social capital for older men and women in the areas in which they functioned. A key factor to explain this finding was that these clinics did not limit themselves to dispensing clinical advice, primary care and medicines. An important function of the neighbourhood clinics was that they addressed the social and psychological needs of the older population by providing a place for them to gather and build their social networks. This in turn enabled better wellbeing and access to resources long after the mobile clinic left the neighbourhood. Evidence from other settings shows that integrating clinical care with socialisation and peer support leads to better health outcomes among the old (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Shuter and Lindsay2009). Neighbourhood clinics also demonstrated that most of the health-care needs for our sample were primary health-care based. This has been shown by other studies that have indicated a need for a reorientation towards routine primary health care, rather than specialised health technology-intensive approaches (Barber and Rosenberg, Reference Barber and Rosenberg2017).

Given the proportion of the older population in Kerala, the state has initiated several programmes to address their health-care needs (Table 4). However, most interventions focus on NCD such as diabetes, hypertension and cardio-vascular diseases, and have converged in the form of the NCD clinic delivered through various health facilities. Palliative care for those who are sick and bedridden is also being implemented across the state albeit in a limited manner. However, a crucial issue that is omitted and has important ramifications for the wellbeing of older people is mental health. Loneliness, depression and psychological distress among older adults and its impact on their wellbeing is well-established (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Taylor, Nguyen and Chatters2016). Loneliness and concerns about the future was a common issue that emerged in our study. While relationships with neighbours and the community did support wellbeing to a large extent, some of our participants found the cultural changes to the family unit distressing, and this clearly had an impact on their mental health and wellbeing. Addressing this requires health systems to move beyond medicalising the issue as they currently do. Depression and anxiety in older populations are often symptoms of loneliness, with lack of social networks being the root cause of these mental health problems. Providing mental health or wellbeing services that are sensitive to the cultural aspect of this phenomenon, including promoting the development of social networks in neighbourhoods, would provide a more fundamental solution to this problem.

Table 4. Programmes to improve health care for the older population

Notes: NCD: non-communicable disease. PHC: Primary Health Centre.

A key intervention under UHC schemes globally and in India has been the provision of health insurance that addresses direct costs associated with accessing health care at the point of service delivery (Giedion et al., Reference Giedion, Alfonso and Diaz2013). While the vast majority of our study participants were covered by either public or private health insurance, it was irrelevant to most of their health-care requirements. This was because health insurance did not cover outpatient primary care or the cost of medication if it had to be purchased. Therefore, while being covered by health insurance, widows continued to pay from their pockets for most of their health-care expenditure. This gap emphasises the need to reconsider whether the present form of health insurance is relevant to the needs of the majority of the older population. Failure to address this issue means the ability to obtain health insurance has no meaningful impact on the widow's ability to access health-care services.

Ageing and the increasing numbers of women who live alone in their twilight years is a new demographic phenomenon in India. The global commitment to ensuring UHC provides an opportunity to ensure that older communities and, in particular, the vulnerable among them such as widows are able to access health care when they require it and remain active members of their communities. This study provides evidence that merely ensuring the availability of health insurance coverage, health-care facilities or medicalising underlying social issues will not ensure UHC. UHC interventions for older populations need to consider the cultural and social contexts of the community and include interventions that promote social capital, prevent social isolation and build local communities. For this to occur, several areas including social and health policy as well as health-care programmes being implemented need to be revisited (Table 5) in the context of the emerging situation of older communities in Kerala.

Table 5. Recommendations for policy and programmes

Note: ASHAs: accredited social health activists.

Limitations

Our study has obvious limitations. The local context and, in particular, the local self-governance unit of the panchayat has a strong influence on the initiatives that are implemented for older widows living under their jurisdiction. A second limitation is the fact that this study has been carried out in Kerala, a highly literate state in India with good public health infrastructure and highly decentralised local self-governance mechanisms. This might not be the case with many other states in India. A final limitation is the fact that our sample is limited to older widows and leaves out widowers. Hence the study might not reflect some issues that would have been pertinent to older widowers and their access to health care. Despite these contextual limitations, we believe that our work sheds valuable insight on mechanisms that promote wellbeing and access to health care for older widows.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all the participants of our study: the widows who participated in our study, doctors, other health-care workers in Kottayam district and the key informants who shared their experiences with us. Many thanks to the Department of Health, Government of Kerala for granting the requisite permissions to carry out this research and to the National Health Mission office at Kottayam for the support provided. A special word of thanks goes to Jessy the ASHA Coordinator of Kottayam and Sr Valsala of Vaikom Taluk Hospital for their role in facilitating data collection. We are very grateful to all the ASHAs who accompanied the lead author and facilitated data collection.

Author contributions

MSG carried out the data collection and drafted the manuscript with contributions from RD, IM, RG, VS and PU. MSG and PU were involved in the analysis of the qualitative data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This work was carried as part of the PhD research of MSG. Field work was supported through a grant available to all PhD candidates towards project expenses at the University of Canberra.

Conflict of interest

MSG, PU, RD, IM and RG declare that they have no conflicts of interest. VS is the district programme manager at the National Health Mission office at Kottayam where fieldwork was carried out. His role was limited to contributing to the drafting of this manuscript.

Ethical standards

The Human Research Ethics Committees of the University of Canberra (20180074) and the Indian Institute of Public Health Delhi (IIPHD_IEC_03_2018) provided ethical approval for this study. Regulatory permissions were obtained from the Kerala Department of Health (GO(Rt)No2677/2018/H&FWD). All participants gave informed consent prior to data collection.