Introduction

On June 5, 1930, the fiftieth annual Burma Dinner was held at the stylish Connaught Rooms in central London. Sir Robert Horne, a well-known Scottish businessman and former chancellor of the Exchequer, presided over the event and began festivities with the yearly “prosperity to Burma” toast and speech. Horne’s focus that night was commerce. After asserting that Burma’s exceptional growth in the 1920s had balanced the ongoing economic depression, Horne argued that “India has been transformed by British people and British capital” and that “we can talk of our exploitation of India with pride.” Horne’s pride was likely unsurprising for those members of the Burma community assembled in London. A member of Parliament for Glasgow Hillhead since 1918, Horne was associated with Burma not through his political connections but through his commercial interests. Horne was, in fact, chairman of the Burma Corporation, a transnational mining corporation that the businessman W. T. Howison would label in his reply “one of the romances not only of Burma, but of the whole mining world.” In his speech, Horne outlined his belief that British commerce did not just line the pockets of the “bloated representatives of the people who have exploited Burma.” Instead, the MP thought that commerce was crucial to the social, cultural, and moral development of the colony, asking, “Where would India have been but for British capital to develop her vast resources and set on foot her different schemes?”Footnote 1

Horne’s remarks came at a significant moment in the history of Britain, its empire, and its economy. Issued at a time when Britain’s long-standing commitment to free trade was at its end, Horne’s missive on the beneficence of commercial agents in British India captured his optimism in the possibilities of a new economic age.Footnote 2 His comments, however, also hinted at a fundamental shift that had occurred over the previous few decades; mainly, the transition from a belief in the inherent separateness between the state and the economy to an understanding that the two were closely linked.Footnote 3 This transformation—which, considering his own dual role as a politician and businessman, Horne himself represented—signified a major change during the late colonial period, particularly regarding the role of business and capital in the making of empire. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, for example, private corporations and individuals held sway over large swaths of foreign land, often independent from the state. With their claims of sovereignty legitimized by charters, treaties, and contracts, the expansion of these private interests—which famously included the British East India Company as well as “rogue empires” such as James Brooke’s rule in Sarawak—not only preceded “official” colonial rule but also provided a framework and justification for subsequent state-directed occupation.Footnote 4

By the turn of the twentieth century, however, this “company-state” model would largely disappear. Although vestiges of the earlier system remained, including the British North Borneo Company, a new emphasis on administrative centralization, border security, and state sovereignty made British officials reluctant to sanction such wide-ranging powers to private enterprise.Footnote 5 Nevertheless, commercial interests and notions of “corporate governance” remained critical to imperial state making in the early twentieth century.Footnote 6 In locations across the British Empire, the significance and reach of British and foreign-owned businesses only increased in scope over the late colonial period.Footnote 7 The days of company rule may have been over, but the business of empire was better and more expansive than ever.Footnote 8

This article focuses on the transformations of the early twentieth century to assess how the often blurry relationship between the state and the corporation evolved from the company-state model that operated in earlier times.Footnote 9 To do so, this paper utilizes a comparative approach that examines the histories of two large-scale private enterprises active in Southeast Asia at this time: the Duff Development Company in Malaya and the Burma Corporation in colonial Burma. A multisited comparative study, this article shows, can reveal much about the overlap between business and governance in the British Empire during the early twentieth century. As Philippa Levine argues, a comparative history that is attentive “to the interplay of local and global” and to “rupture as well as commonality” can highlight broader issues that travel across borders, contexts, and administrative regimes, opening up new insights and avenues of inquiry at an imperial, global, or transnational scale.Footnote 10 Furthermore, a comparative history allows scholars to engage more deeply with the local.Footnote 11 Although many studies—such as Philip Stern’s influential history of the East India Company—examine the relationship between the corporation and the state through a focus on the legal and juridical landscape that underwrote that partnership, a place-based approach can show how a variety of social, cultural, environmental, and spatial factors shaped how a commercial enterprise developed in the local setting.Footnote 12

A comparative approach attuned to notions of place and space also presents an opportunity to locate different voices and source materials in our studies of business and empire. This includes the views and experiences of local political actors, laborers, engineers, managers, and other foreign experts who inhabited these spaces, in addition to the gentlemanly capitalists and metropolitan elites whose stories are often told but who rarely visited their sites of commerce.Footnote 13 To provide a more comprehensive narrative about how the Burma Corporation and the Duff Syndicate evolved on the ground, this article incorporates a wide range of sources that were either neglected or were unavailable in previous decades, such as those found at the Department of National Archives in Myanmar, the Arkib Negara Malaysia, and the recently released colonial administration archives located at the National Archives of the United Kingdom.Footnote 14 Nevertheless, the fragmented archival trail for each firm remains limited, valuing some voices more than others. Although this article prioritizes the entanglements and tensions that linked local company officials and British governmental agents in Burma and Malaya, studies centered around the investing public or the experiences of local indigenous leaders within these broader conversations could reveal other important insights about the complex relationship maintained between the colonial state and private interests in Southeast Asia during the early twentieth century. It is the former such approach, however, that is the focus of this essay.

The histories of the Burma Corporation and the Duff Syndicate, this article shows, provide a useful point of comparison to study the interplay between the state and the corporation in the British Empire. This is because while each company evolved in a unique way and ultimately had a different fate, together they shared a number of important features that make a comparison valuable. Not only were both firms founded at the turn of the twentieth century and celebrated publicly for their supposed state-like qualities, but they were also each located in areas under “indirect” colonial rule in British Southeast Asia. Similarly, both companies were, at least at their conception, mining ventures. Because mining required a unique spatial fix to allow for large-scale development and resource exploitation, the relationship crafted between the colonial state and mining corporations was critical to success. Concerns about land tenure, water, energy, communications, labor, sanitation, and crime all impacted the development of a large-scale mining enterprise, bringing any such operation into direct contact—and, at times, conflict—with government.Footnote 15 In areas distant from colonial state control, this fact was only heightened. Owing to the infrastructure necessary for development, mining firms had to navigate a complex array of policies, legal codes, and rulers to expand their operations, a reality that became even more regulated and convoluted over the early twentieth century. This was, borrowing a phrase, a world of “layered sovereignties.”Footnote 16

Nevertheless, as the divergent fortunes of the Duff Syndicate and the Burma Corporation indicate, the ability of private enterprise to deal with and adapt to an increasingly interventionist state often meant the difference between success and failure in the British Empire during the early twentieth century. Instead of acting outside the colonial administration or on their own sovereign terms, businesses were incorporated within the growing state apparatus, providing services and control in areas where the state was weak, while simultaneously exploiting governmental policies to secure increased accessibility to land and profits. These changes, however, did not proceed evenly or without resistance. Businessmen and colonial officials sparred on a litany of issues throughout the late colonial period, particularly in reference to the rights of companies and the accessibility of land, energy, and communications.Footnote 17 These disagreements colored how the corporation developed as well as how the state expanded its interests into areas under indirect rule. The Burma Corporation and the Duff Syndicate are representative of this. Both conceived at the turn of the century, each firm struggled to adapt to the new economic environment of the late colonial period, with ultimately differing results. Their histories reveal how the relationship crafted between the British colonial government and private enterprise transformed in the early twentieth century. They also show how commercial ventures remained central to the making of the British Empire in the late colonial period, bridging the divide between the age of company rule and the turn toward state-sponsored “development” in the mid-twentieth century.Footnote 18

The Case of the Burma Corporation

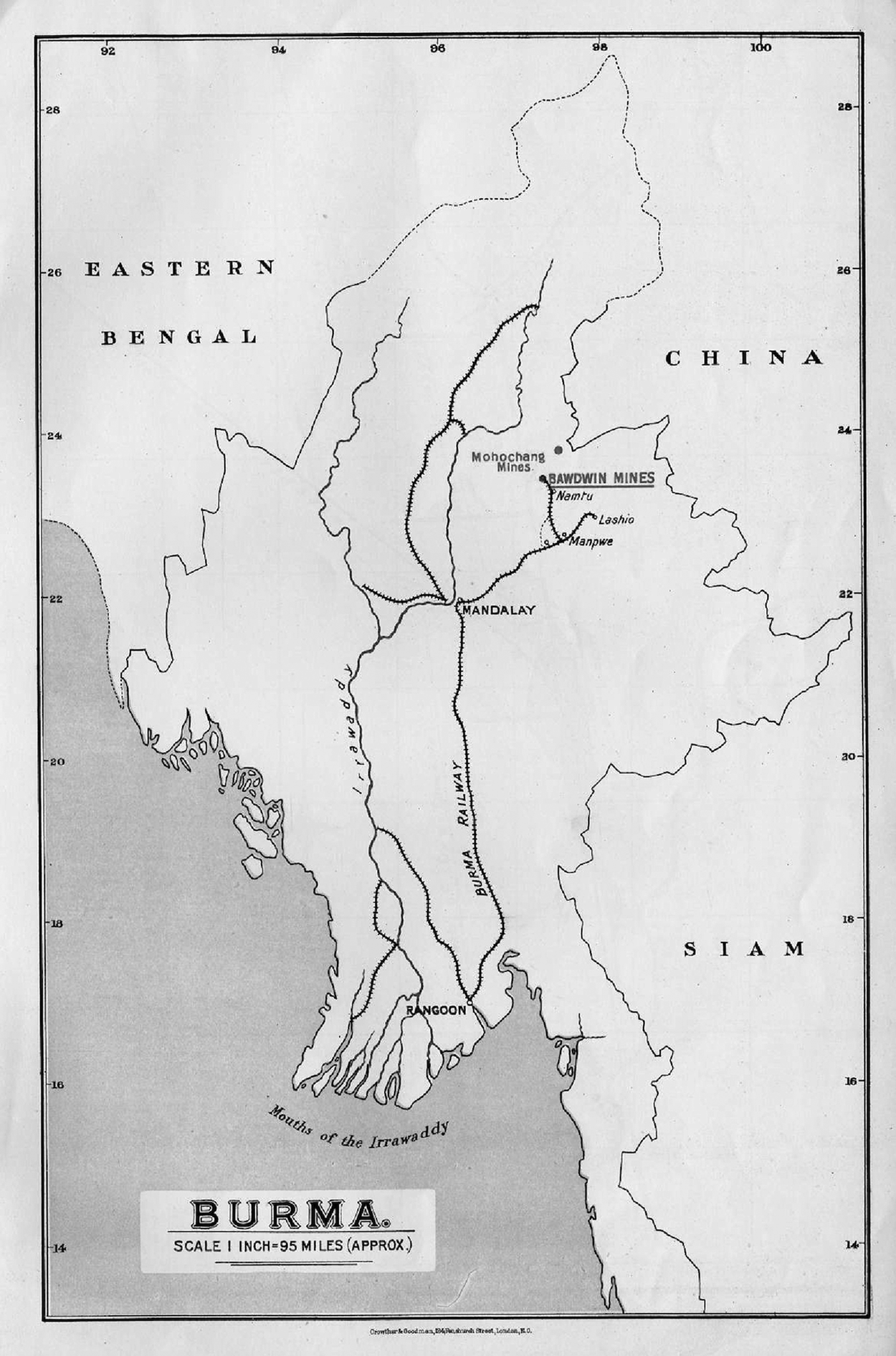

The mining operations at Bawdwin and Namtu were located in an area known as the Northern Shan States of Burma during the colonial era (see Figure 1). Bordering China and Siam in the northeast, the Shan States were a collection of small autonomous states that, in the precolonial period, enjoyed relative independence from Burmese rule.Footnote 19 Bawdwin and Namtu, specifically, were situated in the state of Tawngpeng, an area occupied and ruled by the Palaung ethnic group. Well known for its tea production, Tawngpeng was also the site of considerable industrial activity, a fact that emerged long before British colonial rule in the region.Footnote 20 As early as the fifteenth century, Chinese miners worked the surface of an ore deposit at Bawdwin, which held large concentrations of silver, lead, and zinc. At its height in the eighteenth century, Bawdwin was reported to have upward of twenty thousand Chinese workers laboring at the site, making it one of the largest and most significant mining enterprises in Asia.Footnote 21 Despite this, and likely owing to the outbreak of the Panthay Rebellion, the Chinese abandoned the site in the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 22 It would remain unworked until the turn of the twentieth century.

Figure 1. Map of British Burma and the Bawdwin mines.

Source: Herbert Hoover Presidential Library, Herbert Hoover Pre-Commerce Files, Subject: Mining, Burma Mines 1914.

In the 1880s, British forces occupied and annexed Upper Burma, concluding a series of violent confrontations and annexations that began earlier in the century. At this time, the Shan States became an object of interest for British officials as well as foreign businessmen, the latter of whom saw vast economic potential in the region. Following a period of anticolonial insurgency in the region that lasted into the 1890s, British officials occupied and divided the Shan States into northern and southern administrative units, utilizing a hybrid, indirect system of governance.Footnote 23 In this system, a local sawbwa, or chief, was in charge of law and order in his state, while a British superintendent was stationed in the region to maintain peace and to ensure the proper and timely collection of taxes. Although the presence of British officers in both the Northern and Southern Shan States was minimal, often representing only a handful of administrators, the territory was, in the view of the colonial government, sovereign British territory.Footnote 24 This included the state of Tawngpeng, where the Bawdwin mineral deposit was located.

Following the annexation of Upper Burma in 1886, it did not take long for foreign capitalists to take notice of Bawdwin. Although legends about the silver mines circulated in European circles since as early as the 1820s, it was not until the 1890s that western businessmen first visited the area and discovered the old Chinese workings at the site.Footnote 25 In 1902, the Great Eastern Mining Company—headed by a number of British agents—was granted a lease to the Bawdwin concession, the first western company to hold mineral rights to the deposit.Footnote 26 However, owing to a number of developmental and financial difficulties, the venture was quickly forced to recruit additional assistance. In 1903, the Share Guarantee Trust Limited, led by the Australian R. Tilden Smith, became involved in the firm.Footnote 27 Then, in 1907, the Burma Mines Railway and Smelting Company—thereafter renamed Burma Mines Limited—was founded to take charge of the nascent operations, merging Tilden Smith’s interests with those of a number of other prominent figures in the British mining world.Footnote 28 This included the Australia-based management firm, Bewick, Moreing, and Company, as well as the eminent American engineer and mining financier, Herbert Hoover. Hoover, despite only briefly visiting the mines, became the primary leader of the enterprise during the first decade of operations, recruiting and sending in his own team of engineers from the United States and Australia to develop the site. Although progress initially proved difficult, the company had a breakthrough in 1913 that allowed it to mine deep below the surface for the first time, sparking the rise of large-scale industrial lode mining at the site. Around the same time, the company reorganized its management structure and finances, founding a new company—the Burma Corporation—to represent the enterprise.Footnote 29 These successes would jumpstart a new phase in Bawdwin’s history.

In the years following 1913, the operations at Bawdwin became one of the most significant mining enterprises in the world. Although Hoover was forced out of the firm during World War I, the company advanced rapidly into the 1920s and 1930s, when it became a symbol of industrial success in the colony.Footnote 30 Labeled with a litany of superlatives in the Anglo-Burmese press—including an “Industrial Wonderland” or the “Commonwealth of Namtu”—the mines, by the 1920s, produced and shipped a significant amount of silver, lead, and zinc for the world market, rivaling more famous counterparts in Western Australia and North America.Footnote 31 Located in what was often described as a remote “jungle,” the mining venture was lauded for a number of its supposed achievements, including its use of modern technology and its enlightened labor policies.Footnote 32 For instance, after visiting the mines in 1927, Burma’s governor, Sir Harcourt Butler, noted that while “it is not always realised that Burma owes the main part of its development to the great firms and companies which have sunk … sums of capital” into the province, the Burma Corporation’s feats demonstrated how “without these firms and companies Burma would still be a backward country instead of the progressive country that she is with a world-wide reputation and fame.”Footnote 33 Butler’s successor as governor, Sir Charles Innes, similarly spoke of the significance of private capital to Burma’s development. Visiting Bawdwin and Namtu in 1928, Innes asserted that while he “heard many objections raised to the introduction of foreign capital into India,” he wished that such critics “could be with me here to-day and could see for themselves the benefits of the application of capital, whether foreign or otherwise, to the development of an Eastern country.”Footnote 34 For both Butler and Innes, the mines demonstrated the progressive capacities of private industry, a fact that both celebrated the company’s achievements while also acknowledging the limitations of government. The firm was, in other words, an exemplar of sound corporate governance.

The public narrative that emerged in the 1920s about the Burma Corporation may have celebrated the firm’s governing capacity, but the reality on the ground was far more complicated. Although the corporation adopted policies that would today be categorized under the umbrella of “welfare capitalism,” the British colonial government in Burma also played a critical role in the firm’s development and success, a reality manifest from the very foundation of the venture.Footnote 35 This is because Bawdwin, legally speaking, was the protected property of the British Crown. In the 1890s, when the British formalized their policy of indirect rule in the Shan States, colonial administrators and Shan leaders signed a “sanad”—or contract—that turned over all mineral rights to the colonial government.Footnote 36 Based on the Crown Rights system used elsewhere in the British Empire at this time, the policy forced all prospective firms to seek approval from the Anglo-Burmese government to work a mineral deposit, irrespective of its location.Footnote 37 For the Burma Corporation’s predecessor, the Burma Mines Railway and Smelting Company, this meant that the British state—and not local authorities in Tawngpeng—authorized its lease. This lease, signed in 1906, officially sanctioned the relationship between the company and government, solidifying both the taxes and royalties the firm was expected to pay and the size of the concession.Footnote 38 It also meant that the Burma Corporation, despite operating in an area of indirect rule, was still held accountable to British colonial laws and regulations.

The Bawdwin lease established the parameters for large-scale industrial development at the site, but mining was a horizontal activity as much as a vertical one. Even though the Burma Corporation and its predecessors were legally sanctioned to extract ore at Bawdwin, the spatial requirements of mining quickly forced the company to develop additional areas outside the concession. Access to transportation, in particular, was a central obstacle. Because the ore deposit was located more than fifty miles from the nearest railway, the company required the construction of an additional rail line to transport its commodities to market. Understanding that the government was not in a position to finance the railway’s construction, in 1908, the company instead petitioned the government to support their own construction of the line, a bid that was accepted. Thanks to the support of the Tawngpeng sawbwa, who provided labor for the railway’s construction, the line was finished in December 1909, linking Bawdwin with the state’s railway service for the first time.Footnote 39 Following this, in 1911, the company smelter—located some 250 miles away in Mandalay—was relocated to the nearby village of Namtu, allowing the firm to smelt ore locally.Footnote 40 These advances, which were critical to the survival of the firm, made possible the industrial development that would occur after the discovery of the silver–lead–zinc deposit beneath Bawdwin in 1913. They also began a process of expansion at Bawdwin and Namtu that would accelerate in scale over the next two decades.

By the time of the establishment of industrial lode mining at Bawdwin and Namtu in 1913, the Burma Corporation and its commercial predecessors were bound to the colonial government in numerous ways. In return for the granting of a mining lease, the company was required to pay royalties to the Government of India, which included both fixed royalties on working the site as well as any profits gained from production. Owing to the large-scale industrial nature of the enterprise, the firm was also liable to additional taxes and supervision from the colonial administration. The use of colonial railways—necessary to ship large amounts of metals for export—was taxed at fixed rates, and the building of infrastructure in the region—which included the construction of the company railway, smelters, processing mills, barracks, and other required mining machineries—only increased the amount of land and leases the company required.Footnote 41 Although small in scale initially, by the 1920s, this infrastructure was considerable. Nevertheless, the Burma Corporation required more than just a railway and a handful of government contracts to ensure progress; the company also needed to power its operations. To do so, the firm needed large supplies of energy and labor, two “commodities” that were in short supply in the Northern Shan States during this period. These needs would spark both increasing disputes as well as significant compromises between the company and government. They would also lead to an increase in governmental oversight and regulation in the region, expanding state interests along with those of the Burma Corporation.

The growth of industrial activity at Bawdwin and Namtu enlarged the footprint of foreign interests in the region, but for this to occur, the Burma Corporation required vast reserves of power and energy. Energy, of course, was critical to the functioning of an industrial mining enterprise. Whether to power machinery such as a processing mill or to assist in pumping out groundwater from a mineshaft, mining work required access to large supplies of natural resources to fuel its operations.Footnote 42 At a place like Bawdwin, located in an area of Burma distant from the colonial state infrastructure, this presented a particularly difficult problem. Coal, which was a preferred energy source for mining enterprises at this time, was difficult to obtain in Burma, and shipping costs made the import of the commodity prohibitive.Footnote 43 As a replacement, the company was forced to rely on timber products. Although the area directly surrounding Bawdwin was bereft of wood products—the result of centuries of mining during the Chinese occupation of the site—the company hired local Shan, Palaung, and Kachin villagers to cut wood from the adjoining region.Footnote 44 The need for timber would, however, bring the company into direct conflict with the colonial government. Because forests were under the protection of the state, the clear-cutting of forests frustrated colonial officials who were keen on conservation.Footnote 45 To account for the growing operations at Bawdwin, the government was forced to increase the forest establishment numerous times, causing tension between the two parties.Footnote 46 In 1912, for example, it was reported that unless additional forest agents could be sent to the Bawdwin area, there would “be at the present rate of felling no forests left to reserve” in four years.Footnote 47 Even with the company paying large royalties to fell timber in the area, the company’s destruction of forests in the Northern Shan States tempered the good relationship enjoyed between the corporation and the colonial government.Footnote 48 It also increased the need for state employees in the area.

To solve the energy dilemma at Bawdwin, company officials turned to another power source that, at least in theory, was available locally: water. Like forest products, however, water access required the use of additional land outside the company lease. In 1913, the company sent a proposal to the government to build a power plant above Mansam Falls, located between Hsipaw and Lashio along the Nam Yao River, some fifty miles distant from Bawdwin. In petitioning the government, the Burma Corporation argued that owing to the high costs of attaining both oil and coal for the mines, as well as the issue of deforestation around Bawdwin and Namtu, energy costs were excessively high and were forcing the company to slow production. H. A. Thornton, the superintendent of the Northern Shan States, found the company’s proposal to be a “sound one” and believed that the high costs of fuel and, in particular, the “very great and permanent damage being done to the forests” near the mines were worthy reasons to grant a license to the company. Thornton’s primary concern with allowing the company to build the plant was the possibility that “the beauty of the landscape at and near the Falls may be spoiled.” This “sentimental” reason, however, did not “override the practical benefit which will be secured both to the Government and the Company,” and Thornton recommended the government to issue an approval to the firm. The lieutenant-governor agreed with Thornton, but with an added caveat. Because waterways in the Shan States were not under the same rules that applied to mineral resources, the company had to consult with the “Sawbwas of the States concerned” regarding the “terms on which the water rights and land required in connection therewith should be leased to the Company.” Once that had been completed, along with surveying and building estimates, the company could apply to the local government for permission to the use the falls.Footnote 49

The colonial administration may have supported the Burma Corporation’s proposal to build a hydroelectric power plant at Mansam Falls, but unlike other company-built engineering projects that occurred on site, the Mansam Falls project languished in development for years. This occurred because the company was unable to strike a deal with the local sawbwas—in this case, from Hsipaw and the North Hsenwi States—in regard to royalties, a matter the colonial administration was unable to solve.Footnote 50 Believing that the sawbwas were asking for too much in the way of royalties, the company tabled the project, instead proposing a number of alternate schemes. In 1919, for instance, the company proposed to block an area of the Nam Yao River and build a large lake in the region to “fill the shortage of the food supply” around Namtu. The government, however, denied the request, citing that “the conflict between the interests of the Company and the permanent population will necessitate very careful consideration of the problems involved before any decision ought to be taken.”Footnote 51 Nevertheless, in May 1920, the company’s original plan was finally approved. Under the supervision of a government officer, the Burma Corporation and the sawbwas of Hsipaw and the North Hsenwi States signed a lease that gave the company permission to the build a hydroelectric power plant at Mansam Falls, solving the royalty issue that had plagued negotiations since 1913.Footnote 52 By September 1920, the plant was completed, not only providing a new and significant source of energy for the mining operations, but also extending the reach of the company well beyond Bawdwin’s location in Tawngpeng.Footnote 53

The Mansam Falls project was eventually resolved in favor of the Burma Corporation, but the frustrations of the experience induced the firm to ask the colonial government for increased assistance in the region. In 1916, when the company’s proposal was still in limbo, the Burma Corporation petitioned the government to reorganize the administration of the area and wrest control from the Tawngpeng Sawbwa. The government was reluctant to take such a step. H. A. Thornton, the superintendent of the Northern Shan States during this time, responded that he “would deprecate any proposals” to “withdraw the tract in which the Company is operating from the jurisdiction of the Sawbwas,” which would “not only be unjust, but impolitic to the highest degree.” Instead, Thornton recommended that an assistant superintendent, who would live on site at Namtu, should replace the adviser to Tawngpeng. Although Thornton understood that it was an undesirable time to add “to the cost of administration in the Northern Shan States,” the company was on “so large a scale” that the government could not wait until the end of the war. “The control of the tract in which it operates is so rapidly becoming more and more difficult,” Thornton noted, “that the establishment which was barely sufficient to administer the States before the Company was heard of is absolutely inadequate now.”Footnote 54 A few months later, in December 1916, the government approved Thornton’s proposal, and the first assistant superintendent at Namtu took up his post at the mines.Footnote 55 This position, which would further entangle the interests of the company and the colonial government, would remain in place until decolonization.Footnote 56

The Burma Corporation’s energy crisis reveals how the company became increasingly subject to local and governmental regulations over the early twentieth century, but the surge in population at the site presented a number of other complications. Although initially a small operation, by the 1920s, the mines housed thousands of workers annually, most of whom had traveled to Bawdwin from India and China.Footnote 57 Because the region was not accustomed to a large population, the company was forced to provide many amenities to support its diverse workforce, including living quarters, a company-built store, and an assortment of leisure activities. The need for sanitation, however, became a point for concern. Between 1912 and 1919, a number of outbreaks of disease occurred at the site, including cholera and influenza. The constant threat of malaria, as well as a significant number of injuries and deaths caused by industrial mining work, accompanied these epidemics.Footnote 58 To combat these problems, the Burma Corporation, in concert with government, set up quarantines in the region surrounding the mines. The company also began a new policy of forced hygiene, forcing workers to undergo lice inspections and to take “regular baths.”Footnote 59 These temporary measures, however, soon made way for a more long-term solution. In 1922, and with the support of the colonial government, the company completed construction on a hospital in Namtu. The hospital, which was designed to service not only mine workers but also members of the local community, became one of Burma’s largest health facilities in the late colonial period. It also became a symbol of the company’s supposedly beneficent rule in the Northern Shan States.Footnote 60

Questions relating to land, energy, and sanitation all coalesced into an increasing governmental presence in the area around Bawdwin and Namtu, but law and order was also a concern. Although the area around Bawdwin had minimal police presence at the start of the century, the rising population in the region brought with it an influx of crime. To combat this problem, and beginning in 1908, the superintendent of the Northern Shan States ordered a large increase in the region’s police force, a change financed jointly by the company, the government, and the local Sawbwas.Footnote 61 Manpower, however, was only one way the government policed behavior. Starting in 1920, the British administration applied a litany of legislative acts to the Northern Shan States, including the Burma Criminal Law Amendment Act as well as the Indian Factories Act.Footnote 62 The latter act forced the company to report on a variety of labor-related concerns for the first time, including the annual size of the workforce, the number of hours worked, and most importantly, the details of accidental injuries and deaths that occurred on the mines’ premises.Footnote 63 Additionally, the company became subject to visiting labor commissions.Footnote 64 In 1929, for instance, members of the Whitley Commission visited Bawdwin and Namtu as part of a larger project to supervise industrial enterprises across British India. These forms of government surveillance brought labor concerns to the forefront of colonial efforts to police and regulate industrial activity in the region. They also forced the company to answer questions about its labor policies for the first time, bringing the governance of its large workforce more firmly under the supervision of the colonial state.Footnote 65

In addition to the many changes that occurred on the ground at Bawdwin and Namtu, the Burma Corporation’s financial and management model was also forced to adapt to colonial state intervention. Although the firm was initially operated and chaired by a host of foreign businessmen—including, significantly, the American financiers Herbert Hoover and Arthur Chester Beatty—the company’s management team increasingly came to reflect imperial priorities throughout the late colonial period.Footnote 66 Between 1915 and 1916, for example, the company appointed two officials active in Burma and India—Sir Hugh Barnes, the former lieutenant governor of Burma, as well as Sir Trevredyn Wynne, former president of the Railway Board of India—to its board of directors. Wynne, in particular, became an important addition to the Burma Corporation’s management team, and the company saw his appointment as an important step in building better relations between the firm and the government.Footnote 67 By the 1920s, these connections were further solidified. In 1923, and in an effort to create a British imperial zinc-smelting industry, a coalition of some of the British Empire’s most important mining financiers became the primary shareholders of the Burma Corporation. The reorganized company, led by the Australian business magnate W. S. Robinson, brought in a number of well-connected British commercial agents, including Sir Cecil Budd and Oliver Lyttelton (later Lord Chandos) from the British Metal Corporation, William Baillieu of the Zinc Corporation, and Sir Robert Horne, a former chancellor of the Exchequer in Britain.Footnote 68 Horne, who was a prominent figure in the global silver trade, became the chairman of the company in the 1920s and 1930s, speaking at company functions and promoting the company’s interests in metropolitan Britain.Footnote 69 These changes in the firm’s ownership group sparked a new phase in the Burma Corporation’s history, bringing the company more directly into the control of government in a post–free trade era.

The success of the Burma Corporation reveals how, even in areas under indirect colonial rule, private enterprise was beholden to governmental oversight in the early twentieth century. Although ostensibly a story of industrial achievement and sound corporate governance, the firm’s history instead demonstrates how the company-state model of the preceding centuries evolved at this time, as well as how the interests of business and government increasingly intersected. Success in this environment, however, was never assured. Without constant adaptation and compromise on the part of both company and state, the ability of private enterprise to prosper in areas under indirect rule was always in peril. These dangers would confront one other mining firm in Southeast Asia at this time: the Duff Development Company in British Malaya. Located in the largely autonomous state of Kelantan, the story of the Duff Syndicate uncovers the difficulties and waning viability of private administration in the British Empire during the late colonial period. It also shows how the “rogue empire” era of corporate governance made way for a new regulatory system of state supervision in the colonial setting, one that was not always embraced by its commercial agents.

The Case of the Duff Development Company

The Duff Development Company, also known as the Duff Syndicate, was created in 1900. Named after its founder, the former British colonial official R. W. Duff, the firm’s operations were based in the state of Kelantan, located on the east coast of the Malayan Peninsula (see Figure 2). Kelantan, at the time of the company’s founding, was independent from British colonial rule. Situated between Siam and the British-occupied Federated Malay States, Kelantan was governed by a local raja, who passed laws, levied taxes, and promoted local customs.Footnote 70 Although this meant that the state was self-governing, a period of political turmoil in the 1890s threatened the area’s autonomy. Following an outbreak of anticolonial violence in the neighboring state of Pahang, which had only recently become a British protectorate, rebels fled into Kelantan and were pursued by British troops. The rebellion, though quickly subdued, brought British forces into the region for the first time.Footnote 71 This included the British advisor to Pahang, Hugh Clifford, as well as Pahang’s superintendent of police, the latter of whom recognized the area’s significant economic potential. That man was R. W. Duff.Footnote 72

Figure 2. Map of the Duff Development Company concession in Kelantan, ca. 1908.

Source: W. A. Graham, Kelantan: A State of the Malay Peninsula (Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons, 1908).

Expanding British interests in the region prompted R. W. Duff’s first visit to Kelantan, but at least initially, British officials in Malaya were uninterested in permanent administration. Although a local leadership struggle among Kelantan elites in the 1890s played on British and Siamese interests in the region, the British government remained neutral into the twentieth century so as to avoid a broader geopolitical conflict.Footnote 73 Nevertheless, R. W. Duff saw an opportunity. In 1900, Duff retired from the British colonial civil service and brokered a deal with the raja of Kelantan to attain a concession in the state.Footnote 74 The deal, signed in October 1900, provided Duff and his firm the rights to three thousand square miles of land as well as “all commercial rights of every kind mining and otherwise within the area of [the] concession.”Footnote 75 For his part, the raja received a cash payment as well as shares in the company.Footnote 76 The deal, however, was highly controversial. Because the deed effectively made Duff a “sovereign” power “even more independent” than “Brooke of Sarawak,” as the historian K. G. Tregonning later referred to it, the situation was troubling for Britain and Siam alike.Footnote 77 While Siam was concerned that a British agent—particularly a former colonial official—held such unconstrained power in a territory it considered its own, the British were equally anxious about Duff’s intentions and the potential fallout from his behavior.Footnote 78 Nonetheless, and following a protracted period of negotiation, both parties agreed to the validity of Duff’s claim. Additionally, in 1902, Siam, Britain, and Kelantan agreed on a treaty that asserted Siam’s control over the state, with the added compromise that a British officer—W. A. Graham—would be sent to act as an official advisor.Footnote 79 Graham would play a significant political role in Kelantan throughout the Duff Development Company’s early years.Footnote 80

When the Duff Development Company was founded in 1900, the firm’s commercial interests were diverse. The concession, which encompassed nearly a third of the landmass of Kelantan, provided access to a variety of economic pursuits, including timber extraction and land for farming and estate cultivation. Yet, at its inception, the company was primarily positioned as a mining venture.Footnote 81 In 1902, correspondence from within the firm noted that while the company held “an immense tract of country with almost unlimited possibilities,” the mineral wealth of Kelantan would “naturally be the first consideration which will appeal to the shareholders.” Though not an engineer himself, Duff recruited a number of geologists and mining experts to advise him on the mineral possibilities of the region, including Walter Chappell, Robert Swan, and a Mr. Indir.Footnote 82 Based on their reports, Duff concluded that the area contained large deposits of gold and silver, the former of which became the firm’s primary interest. According to reports from the period, Swan was “of [the] opinion that what gold is to be won in the Malaya Peninsula” was found in one particular slate wall, “and our concession contains this slate from end to end.”Footnote 83 In addition, Duff was advised that the rivers in Kelantan were gold bearing and suitable for dredging operations, a new technology at this time.Footnote 84 Nevertheless, the company remained cautious. Though correspondence noted that the firm was working to ascertain the value of the property’s mineral reserves, the size of the concession made such a task slow and difficult. “The result of these operations,” one report summarized, would “furnish just so much information as to the value of the property as would result from counting the coin in the hands of a bank cashier if one were seeking to ascertain the capital of the bank.”Footnote 85

Despite his restraint, Duff remained optimistic about the company’s prospects during its early years. With the earlier political difficulties “entirely removed,” and because its commercial rights were “more generous” than the conditions “on which any similar rights have ever been worked before,” Duff felt that the significant value of the property was nearly assured.Footnote 86 Nevertheless, there were complications. Although the company quickly moved to develop the region—which included the commencement of gold-dredging operations, rubber planting, and the construction of a sawmill—progress proved slow, and the company continuously operated at a loss.Footnote 87 In addition, the relationship between the company and the government of Kelantan produced considerable tension. Because the firm was reluctant to relinquish any rights to their territory, Kelantan’s government—particularly the British advisor to the government, W. A. Graham—became concerned about a number of problems, especially over import duties and land tenure for indigenous inhabitants within the concession.Footnote 88 To remedy the situation, and under Graham’s supervision, Duff and the raja of Kelantan compromised on a new contract signed in 1905. The contract forced the firm to cede some of its independence in exchange for the granting of various monopolies. This not only included monopolies on items such as mineral rights, farming, and timber, but also the sole rights to promote the construction of roads and railways within the concession. These railways rights, despite being one small aspect of the negotiations, became a central concern for the company in the ensuing years.Footnote 89

Between 1905 and 1909, the Duff Development Company continued to flounder. While its concerns in timber, farming, and rubber planting showed signs of promise, a fierce and ongoing dispute with W. A. Graham over issues such as land laws within the concession threatened the ability of the company to expand its operations.Footnote 90 In addition, the firm’s primary economic interest—industrial mining—stalled in development. Gold dredging, which brought in some income during this period, produced low yields, and the firm’s most encouraging prospecting site—a large mineral deposit at an area named Liang Camp—was located in a remote part of the concession.Footnote 91 The state of transportation in the concession was a particularly vexing issue. Although company engineers and foreign mining experts who visited Liang Camp were convinced about the deposit’s vast potential—even sinking a number of shafts and importing boilers to the site—the mines were located in dense jungle far from existing modes of transport.Footnote 92 Local waterways, which the company initially hoped could sustain the business, quickly became untenable for the transit of machinery, owing to both high costs and unreliable service.Footnote 93 A solution, however, never materialized. Between 1903 and 1906, the company sent a series of appeals to both the Siamese and Kelantan governments to assist in the construction of railways to service the area, but their offers were rejected.Footnote 94 In 1908, and with frustrations at their peak, the chairman of the company—the mining magnate, Francis Osborne—as well as the chief mining engineer—John Taylor Marriner—resigned from the company, the latter owing specifically to his dissatisfaction with the situation at Liang Camp.Footnote 95 The mines were subsequently abandoned.Footnote 96

By 1908, the Duff Development Company was in a dire position. With the company’s mining work in disarray and its rubber prospects still developing, R. W. Duff reported to the British government that the company held only £12,000 in working capital and was in danger of going out of business.Footnote 97 Nevertheless, Duff remained hopeful. In 1908, Siam and Britain agreed to a deal to cede the rights over Kelantan to the British colonial government, an agreement that was officially sanctioned in 1909. With the deal, Kelantan became part of the Unfederated Malay States, a collection of territories that were administered under indirect British colonial rule.Footnote 98 Duff, for his part, welcomed the agreement. In a letter to the secretary of state for the colonies, Lord Crewe, Duff noted his “satisfaction” over the new deal, adding that the company would “loyally co-operate” with the government “in aiding the administration of the State.”Footnote 99 Duff reinforced these views in public. At the company’s annual meeting in 1909, the founder expressed his “confidence” in the agreement, believing that “under British rule any capital invested in Kelantan would be properly safeguarded.” Even still, Duff knew that the firm would need to reach a compromise with the new British administration regarding the company’s extensive rights. With new regulations and a fresh administrative regime in the region, Duff understood that the company’s fate depended on maintaining a stable relationship with the colonial government, who he anticipated would finally provide the support necessary for large-scale development.Footnote 100 These hopes would never come to fruition.

The 1909 deal ushered in a new era for the Duff Development Company, but despite its promising start, conflict ultimately defined the relationship between the firm and the new administration. This occurred for a variety of reasons. The first issue involved the rights the company secured under the 1905 agreement with the raja of Kelantan. In 1909, the governor of the Straits Settlements, Sir John Anderson, told R. W. Duff that the company’s rights “were such as ought only to be exercised by Government” and that their continuance would “lead to friction between the Government and the Company to the detriment of both.” The government was particularly concerned about the indeterminate size of the concession, the company’s privileges of taxation, and their farming monopolies. Starting in 1909, Anderson and Duff began negotiations on a deal that would have seen the company surrender certain rights for monetary compensation, but the two parties could not agree on a price and the talks were tabled.Footnote 101 Another major problem involved railway extensions. In March 1909, at the same time the Anglo-Siamese agreement was passed, the British government in Malaya also brokered a deal with Siam to loan the country £4,000,000 to build a railway connecting Singapore with Bangkok. This railway, which was designed to pass directly through the Duff concession in Kelantan, would have connected the firm’s operations by rail for the first time. Duff, however, rebuffed the proposal. Arguing that under the 1905 lease, the company alone had the rights to construct roads and railways in the concession, Duff believed that the deal violated the company’s rights and could only be sanctioned once the government and the company agreed to a deal. A deal, for Duff, meant considerable financial compensation.Footnote 102

Many British officials in Malaya were supportive of the Duff Development Company and lauded its efforts in the region, but the negotiations between the company and the government proved combative.Footnote 103 Nevertheless, in 1912, the two parties agreed to a new contract—labeled the “Deed of Cancellation”—that engendered immense changes for the firm. As part of the deal, the company agreed to surrender much of its concession—down to fifty thousand acres—as well as its railway rights in exchange for £300,000 and a commitment from the government that it would finance and build a cart road and railway through the Duff concession. The railway, which the company hoped would finally allow for industrial development in the region, was the fulcrum of the deal. Once the government agreed to the path of the railway, the company then had twelve months to select the blocks of lands they would keep. The government, for its part, had until July 1916 to construct the road and railway. There was, however, a major problem. Although Duff thought the government would build the line directly through the old concession, passing near the mineral deposit at Liang Camp as well as the company’s principal rubber estates, government surveyors proposed an alternate route that bypassed that area entirely. Duff, incensed by the change in plans, argued that this represented a breach in contract.Footnote 104 In response, the company entered into arbitration hearings with the government in 1915 to ascertain the potential damages made to the firm’s financial standing, a hearing that was decided in favor of the local government. Duff, for his part, was not satisfied. Beginning in 1918, the firm once again entered into legal negotiations with the government, a process that lasted for the next seven years.Footnote 105 This time, Duff won. In 1925, a British court ruled that the Kelantan government was liable to pay the Duff Development Company £378,000 in damages, a number that was arrived at largely due to the estimated earnings and royalties the company lost from its mining concerns.Footnote 106 Ultimately, the railway through Kelantan would not be finished until the early 1930s.Footnote 107

The 1923 court ruling represented a moment of victory for Duff, but despite the enormous financial windfall that accompanied it, the company never attained the measure of success it hoped for. Although the firm transitioned its commercial pursuits into timber and rubber and remained active throughout the late colonial period, the company’s work as a mining venture represented a significant failure.Footnote 108 For Duff, the source of this failure was the British colonial government. Speaking to company shareholders in 1916, Duff argued that the while “there were no Imperial or other great interests which clashed with their own,” the government would be “failing in their duty to the company if they allowed their rights to be taken from them without fair compensation.” Duff believed that the company was a “pioneer” in Malaya. Not only did they arrive and secure British interests before the colonial occupation of Kelantan, but they also “rendered services to British commercial interests generally in the country.” In return, Duff believed that the company “might not unreasonably look” for “sympathy and whole-hearted assistance from the Imperial Government.”Footnote 109 It was this sympathy and support, in the end, that Duff had sought since as early as 1900.

Nevertheless, Duff’s story of victimization at the hands of government represented only one perception of how and why events unfolded as they did. In fact, the saga of the Duff Development Company was an object of fascination for a variety of outsiders during the late colonial period, many of whom provided their own narratives about the company’s fate and what its history ultimately personified. Labeled an “imperium in imperio,” the Duff concession—and particularly R. W. Duff’s own “pioneering” story—was for some a symbol of the “romance and adventure” that lay hidden on the imperial frontier as well as the important role that businessmen played in revealing its secrets.Footnote 110 For others, the story was more complicated. Writing in 1912, Arnold Wright and Thomas H. Reid believed that while Duff showed how “the spirit of adventure which has stood our Empire in such good stead at different periods of our history is still a living force,” such an achievement belied the firm’s ultimate failure. This failure, they argued, was less an issue of governmental overreach than it was a product of historical context and circumstance. Because the company was a “modern Malayan prototype” of the “old trading company” of the nineteenth century, Wright and Reid believed that its failure—or at the least, its confrontation with the British government—was inevitable. With a tolerance for private fiefdoms waning, Duff’s firm came up against a new and evolving commercial landscape during the late colonial period, one that made private and state interests interdependent and increasingly demanding of compromise. The Duff Development Company, in other words, was not the victim of a government conspiracy against big business. Instead, it simply came of age at the wrong moment in history.Footnote 111

Conclusion

The divergent fortunes of the Duff Development Company and the Burma Corporation demonstrate how the relationship between the corporation and the British colonial state transformed in the early twentieth century. R. W. Duff, in an effort to protect his company’s rights at all costs, battled with a succession of local administrative regimes over issues such as taxes and communications, a fact that ultimately impeded the firm’s progress. The Burma Corporation, on the other hand, adapted. Although it initially operated with considerable independence, the venture was gradually encompassed within the broader British colonial state–making apparatus, allowing it to expand its industrial operations on a large scale. In both cases, the colonial state loomed large. Whether through the control of land and natural resources, the imposition of taxes, or the policing of boundaries and bodies, state support became critical to the expansion and success of corporate interests in the British Empire during the late colonial period, including in areas under indirect rule. These circumstances were even more pronounced for mining firms. With an overwhelming need for manpower, land, energy, and communications, industrial mining companies were especially reliant on the British administration to assist in their development. As the saga of the Duff Syndicate demonstrates, however, not all private interests embraced this reality.

These facts make a comparative study between the Burma Corporation and the Duff Development Company particularly revealing about the complex relationship maintained between state and private interests in the British Empire during the late colonial period. Despite operating in British Southeast Asia at the same historical moment and in areas similarly under indirect colonial rule, the histories of these two firms demonstrate how a litany of issues—from the vagaries of local administrators to the exact geographic location of a mineral deposit—could impact commercial success in the colonial setting. Additionally, their stories show how the boundary between corporate and governmental structures became increasingly unclear in the early twentieth century. This understudied reality may have had broad consequences across the British imperial world. While in the United States, historians have focused considerable attention on the role of the corporation as an agent of political change during the twentieth century, notions such as “corporate liberalism” have received less deliberation in the context of the British Empire.Footnote 112 Nevertheless, the transnational corporation played a critical role in the expansion and governance of the empire. To succeed, these corporations needed to work alongside and within existing British administrative power structures, making them increasingly reliant on the colonial state. Power, though, worked both ways. To finance its empire, British officials often required the help of corporate enterprises to fulfill duties normally reserved for government, particularly in borderland or frontier areas distant from state control. These mutual interests brought the state and the corporation into closer contact during the late colonial period, presaging the turn toward “economic development” in the mid-twentieth century.