This article concerns business practices adopted by private-sector financial institutions for the purpose of safeguarding cultural heritage. Although considerable attention has been paid by the banking industry to the protection of UNESCO World Heritage Sites (WHSs)Footnote 1 inscribed under natural criteria (see WWF 2015, 2016, 2017), initiatives for cultural-heritage preservation have received less attention. Whereas some authors have looked at the heritage-management policies of multilateral development banks such as the World Bank (see Fleming and Campbell Reference Fleming, Campbell, Messenger and Smith2010; Lilley Reference Lilley2013; Mason Reference Mason2012), investment law and arbitration for cultural heritage (Vadi Reference Vadi2014), and corporate social responsibility for cultural heritage (Starr Reference Starr2013), the literature is largely silent on the role of private-sector financial institutions and their approach to the management and protection of cultural heritage. This is significant as these banks represent the bulk of global investment, and their potential impact on cultural heritage is far greater than that of development banks.

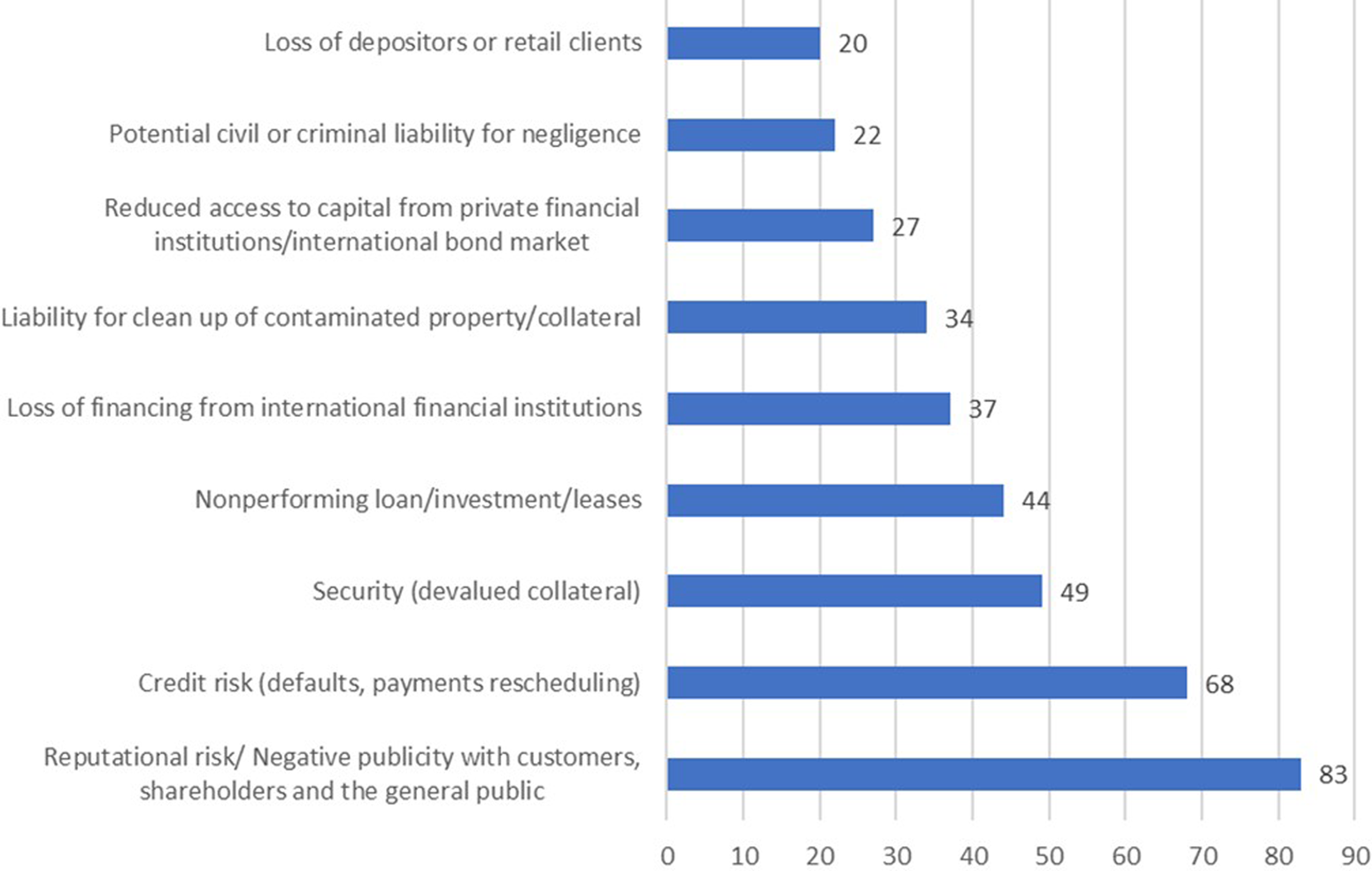

Financial institutions adopt governance structures that protect business interests, promote sustainable practices, and manage their risk exposure. Consistent with this approach, financial institutions typically avoid projects that will have significant adverse effects on the environment and society, including cultural heritage. Key social and environmental risks identified by commercial banks were compiled by the International Finance Corporation (IFC 2010) and are summarized in Figure 1. Reputational risk and credit risk are of greatest concern for respondents—at 83% and 68%, respectively. Reputational risk involves negative perceptions of a company's conduct or business practices that may prevent it from being able to establish new customer relationships or maintain existing relationships. Credit risk relates to the likelihood of a borrower to default on an investment.

FIGURE 1. Key Environmental and Social Risks Identified by Commercial Banks.

Developments that significantly impact cultural heritage can lead to protests, negative media portrayal, or condemnation by influential nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) such as the International Council on Monuments and Sites. This stigma can extend to institutions that provide project financing and can adversely affect their reputation. For this reason, investors and investment managers increasingly choose to apply environmental, social, and governance criteria to financial decisions. The case studies provided below illustrate how projects associated with significant adverse impacts on cultural heritage can affect both financial institutions and development proponents.

A consortium of export credit agencies consisting of Euler Hermes Kreditversicherung (Germany), Oesterreichische Kontrollbank (Austria), and Schweizerische Exportrisikoversicherung (Switzerland) suspended export credit guarantees for Turkey's Ilisu Dam project on the Tigris River over the proponent's failure to meet World Bank standards for environmental and heritage protection (Igra Reference Igra2009; Starr Reference Starr2013). The dam project, which includes a reservoir measuring 313 km2, will inundate a large number of heritage sites including the ancient town of Hasankeyf, which has been occupied for 12,000 years and was a staging post on the Silk Road (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Hasankeyf, Turkey (Getty Images).

The ability of companies to expand and operate in new jurisdictions may also be impacted if significant cultural-heritage resources are adversely affected. For example, Walmart became the target of considerable negative media scrutiny for its decision to build a store close to the prehispanic city of Teotihuacan WHS in Mexico. The development led to allegations of corrupt business practices, destruction of significant archaeological finds, and circumvention of the development permit process (Barstow and Xanic von Bertrab Reference Barstow and von Bertrab2012; Starr Reference Starr2013).

A subsequent UNESCO Reactive Monitoring mission was sent to investigate the allegations, and it determined that the Walmart store did not affect the fabric of the WHS. It did, however, acknowledge that the store had a negative impact on the symbolic value of Teotihuacan and that indirect impacts stemming from the construction of the Walmart—as well as from anticipated new development in the same area—need to be better assessed and planned so that the cumulative effects of such developments do not adversely affect the integrity of the archaeological property (UNESCO 2005a).

There are many other examples of projects that have been delayed or cancelled due to concerns over impacts to cultural heritage. One well-known example is Gabriel Resources' Roșia Montană gold mine project in Romania, which, if approved, would have damaged Roman-era mine workings (Figure 3). Ultimately, the Romanian government protected Roșia Montană village, along with a 2 km radius area around it, from mining by declaring it a historic site of national interest (Agence France-Presse 2016). The government ultimately added it to Romania's World Heritage Tentative List as the Roșia Montană Mining Cultural Landscape (UNESCO 2017). In response to this decision, Gabriel Resources is seeking $4.4 billion for alleged losses. Both parties have agreed to arbitrate the consequences of these actions pursuant to policies from the World Bank Group's International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes. The property was put forward for inscription on the World Heritage List in 2018 but was subsequently referred back to the Romanian government (at the government's request) until the international arbitration matter is solved (UNESCO 2018a). At the time of writing, the proceeding is ongoing (ICSID 2019).

FIGURE 3. Roman mining gallery in Roșia Montană, Romania (courtesy of Gábor Barton).

Another high-profile case is playing out in Afghanistan, where in 2007, the China Metallurgical Group Corporation invested approximately $3 billion in a proposed open-pit copper mine. Since the 30-year lease was signed, the project has gained international press attention, owing to the potential impact on Mes Aynak—a 5,000-year-old walled Buddhist settlement (Amini 2017; China Mining Association 2015; Figure 4). Given this project's potential effect on cultural heritage and other project considerations (i.e., commercial terms and security), plans to develop this property have stalled (Marty 2018).

FIGURE 4. Seated Buddha at Mes Aynak, Afghanistan (Saving Mes Aynak, photo by Brent Huffman).

At a more modest scale, Century Group HQ Development Ltd.’s proposed mixed residential and commercial development on an Indigenous village and burial site in Vancouver, Canada, led to protests and civil disobedience (Howell Reference Howell2012; Figure 5). After 18 months of negotiations, the project was cancelled, and the proponent incurred a significant loss on its investment (Woo Reference Woo2013). Regardless of the scale or location, project delays or cancellations owing to their effects on cultural heritage can result in significant financial loss for both lenders and borrowers. This is particularly relevant to lenders given that banks often cover as much as 70%–80% of project costs (Wexler Reference Wexler2008).

FIGURE 5. Marpole midden development protest, Vancouver, Canada (courtesy of Dan Toulgoet, Vancouver Courier).

Within this context, this article examines the policies ascribed to cultural heritage in the lending practices of 25 of the world's largest banks and promotes certain best practices. These are important considerations for heritage practitioners who may be retained to undertake heritage studies for development proponents or financial institutions.

METHODS

In 2017, when we began to work on this article in earnest, we decided to focus on the practices of the world's top banks, with the idea that this would reflect the approach of those industry leaders with the greatest capacity to engage in best practices. We next needed to decide how to select the banks. Specifically, what were the leading banks at the time? Research soon showed that there are numerous ways to rank banks. Ultimately, we chose to use market capitalization—the value of a company's outstanding shares—as the leading indicator to identify these banks (Table 1; Relbanks 2017). Obviously, ranking systems are not static, and with the passage of time, they can change. Through 2018 and 2019, we checked the rankings for change, but ultimately chose not to alter our original selection. Although some changes occurred over this time, the 25 banks from 2017 were still “leading banks” and appropriate for our assessment of their practices with respect to cultural heritage. Furthermore, we noted that the 2017 banks have greater geographic distribution than those that made the list in subsequent years. They are, therefore, more likely to exhibit variation (if such is present) among top-flight banks.

TABLE 1. Leading Private-Sector Banks and Information Request Responses.

Researching the heritage-management policies of major financial institutions posed two significant challenges. First, both authors are based in Vancouver, Canada, which is not a global financial center. HSBC's Canadian headquarters is the only significant corporate banking presence in the city. The second challenge relates to the paucity of published literature on the topic.

As a first step—and because five of the 25 banks are Chinese institutions—a comprehensive internet search in English and Mandarin was completed for banks listed in Table 1 to identify relevant policy documents. Next, we submitted an information request to each bank, asking for details on its policies and practices with respect to cultural heritage. Finally, given that Mason was traveling to China in 2018, Global Affairs Canada, the agency that manages Canada's diplomatic and consular relations, was asked to arrange information meetings for Mason with Chinese banking officials in Shanghai to supplement the limited information available online.

MANAGEMENT OF CULTURAL HERITAGE IN PRIVATE-SECTOR BANKS

Our internet keyword search for each financial institution yielded results for each bank, although the level of detail varied, and in some cases, it was difficult to determine if the documents were current or representative of actual practices. Documentation for banks based in Europe, North America, South America, and Australia provided the greatest detail. Documentation for financial institutions from China and Russia was less detailed and more difficult to locate. The quality of documentation produced by Sberbank noticeably declined after 2014.

With respect to direct information requests, 13 of the 25 (52%) financial institutions responded (Table 1). Two of these respondents, ICBC and Itaú, indicated that they were unable to provide the requested information. In the case of ICBC, we were told that the online query tool we used was only for ICBC business in mainland China and that our query was outside of their business scope. With respect to Itaú, we were informed that the communication channel we queried was strictly responsible for handling complaints of illegal acts and for checking accounts. The information we sought would have to be obtained from elsewhere in the organization. Alternate contact information was not provided, and further online research was not successful in revealing another access point.

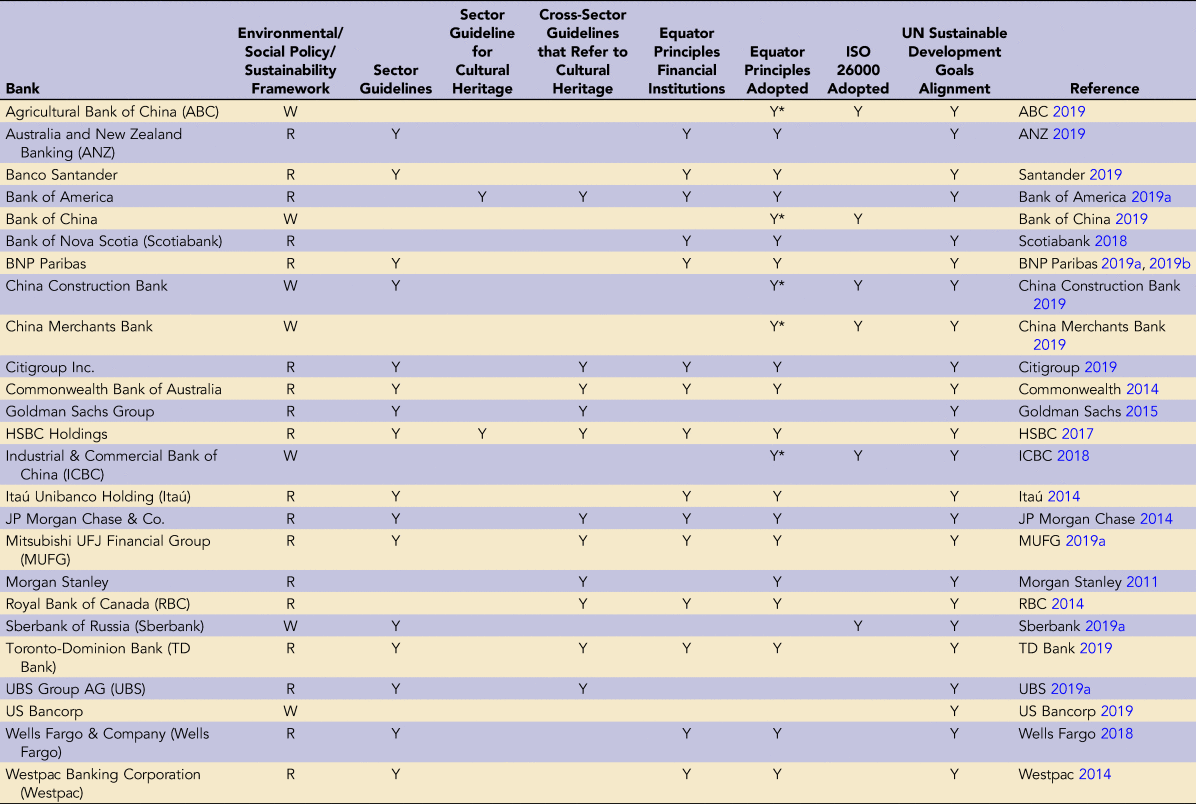

Table 2 summarizes the results of our research and analysis, which is described in greater detail below.

TABLE 2. Review of Cultural Heritage Management in Private-Sector Banks.

Notes: W = Weak; R = Robust.

* Inferred based on requirements of the China Banking Regulatory Commission (2014).

Environmental and Social Policy Frameworks

In addition to adherence to host-country heritage laws and regulations, our research found that all banks adhere to some form of environmental- and social-policy framework. Organizations also refer to them as sustainability- or risk-management frameworks, but despite the different names, their content is similar. They outline both internal and external expectations and requirements for the management of environmental and societal issues in the banks’ deals and include consideration of project effects on cultural heritage. Our analysis included a qualitative assessment of available information on the frameworks used by each bank and categorized them as either robust or weak. Most examples are detailed and robust. Weak examples include those from Sberbank, US Bancorp, and all of the Chinese banks. In these seven cases, information pertaining to their environmental and social policy frameworks lacked substance.

To address the limited information available from Chinese financial institutions, we broadened our research to include requirements placed on banks by the Chinese banking regulator. Research revealed the China Banking Regulatory Commission (2014) provides requirements for cultural-heritage safeguards in its sustainable-finance/lending-key evaluation checklist. According to the checklist, Chinese banks working overseas are required to align their lending practices with relevant international guidelines and to meet industry best practices. International guidelines include the Equator Principles (see below), UN Global Compact (2014), UN Financial Initiative, and the UN Environment Programme Statement of Commitment by Financial Institutions on Sustainable Development (UNEP 1997). Furthermore, banks are obliged to consult with relevant regulatory agencies and engage qualified and independent third-party consultants to undertake a due diligence review of project environmental and social risks. Chinese banks must implement this checklist in their day-to-day business and provide an annual report on their performance to the China Banking Regulatory Commission.

To further understand Chinese bank practices, Global Affairs Canada in Shanghai, China, shared a draft copy of this article and attempted to arrange information meetings for Mason with the following institutions: Agricultural Bank of China, Bank of China, Bank of Communications, China Construction Bank, China Minsheng Bank, and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China. Unfortunately, Mason's travel through Shanghai coincided with the China International Import Expo, and Global Affairs Canada was unable to secure meetings at such a busy time. Global Affairs was, however, able to share a number of points that came up consistently in its conversations with representatives of these Chinese banks:

• Chinese banks are conservative when encountering projects involving significant cultural heritage.

• They view cultural heritage as a niche concern, and they do not have a dedicated person or team to address this consideration.

• The decision whether to retain an external subject matter expert (SME) to provide support to the risk-control groups within financial institutions is mostly done from their head offices (Beijing).

Sector Guidelines

Among the important features of environmental- and social-policy frameworks are sector-specific guidelines for certain industries or activities and cross-sector guidelines or prohibited/restricted activity lists (Table 2). For industries or activities captured under these policies and guidelines, banks will not provide finance, or they will require enhanced environmental and social due-diligence measures before agreeing to provide financing.

Examples of sector-specific guidance include those for nuclear power, cluster munitions manufacturing, and palm oil. Bank of America and HSBC have sector-specific guidance for activities within WHSs. Bank of America will not knowingly finance natural resource extraction in WHSs unless there is prior consensus between UNESCO and the host-country government that the proposed activities will not adversely affect the natural and cultural value of the site (Bank of America 2019a). HSBC will avoid financing projects that could result in a WHS being placed on the UNESCO “In Danger” list (see Cameron and Rössler Reference Cameron and Rössler2013; Meskell Reference Meskell2013), unless the World Heritage Committee supports the project. In addition, HSBC proceeds with extreme caution where a change in the boundary of a WHS is proposed to accommodate a new project. Finally, low-impact activities that are compatible with the preservation and protection of WHSs are exempted from the HSBC policy (HSBC 2014).

Cross-sector guidelines and “prohibited lists” offer guidance that applies to all areas of banking activities. Examples include impacts on Indigenous Peoples, involuntary resettlement, modern-day slavery, and child labor. Eleven (44%) of the banks examined in this analysis have cross-sector guidance for industries and activities that refer to cultural-heritage protection, specifically with respect to WHSs (Table 2). Although not universal, sector and cross-sector guidance on WHSs has a noticeable bias toward natural and mixed-criteria sites. This may reflect the greater effectiveness of the environmental lobby or may simply be a function of the larger size of these heritage properties and their vulnerability to impacts from extractive industries such as mining or oil and gas.

External Guidance

In addition to adhering to host-country heritage laws and implementing an environmental and social policy framework, most financial institutions voluntarily adopt international standards, or best practices, for managing environmental and social issues. Our research identified two external standards, the Equator Principles (EPs) and ISO 26000, along with one external framework, the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs; Table 2). Of the 25 financial institutions examined in this article, 22 follow either the EPs or ISO 26000. Goldman Sachs, US Bancorp, and UBS do not adhere to either. Twenty-four (96%) of the banks examined in this study explicitly align their businesses with the SDGs. Only the Bank of China is silent on support for the SDGs. The sections that follow will describe the provisions of the EPs and ISO 26000 that safeguard cultural heritage, as well as those aspects of the SDGs that relate to cultural heritage.

Equator Principles

For private-sector financial institutions, the EPs were established as a voluntary credit-risk management framework to be adopted by the world's leading financial institutions (now known as the Equator Principles Financial Institutions, or EPFIs). Fifteen of the banks profiled in this article are EPFIs. Morgan Stanley adheres to the EPs but is not considered an EPFI. None of the Chinese banks explicitly adopt the EPs, but as noted above, the China Banking Regulatory Commission requires EP alignment by Chinese banks working overseas. However, given the absence of any reference to the EPs in documentation prepared by the five Chinese banks, the authors consider these banks’ actual adoption of the EPs to be questionable.

Adoption of the EPs stipulates that projects of a certain threshold be developed and operate in accordance with good international environmental and social standards. The EPs are internationally recognized and based on IFC Performance Standards (see below) and on World Bank Group Environmental, Health, and Safety Guidelines (World Bank 2007). The EPs are typically adopted on a per-project basis, according to the magnitude of the project's potential environmental and social risks and impacts. They provide a means to categorize, assess, and manage environmental and social risk in the context of project finance, and they offer a minimum standard for due diligence to support responsible risk decision-making for EPFIs (Equator Principles Association 2013).

EPFIs will only finance or provide project-related loans to projects that meet the requirements of Principles 1–10. Principles 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7 have the most direct bearing on the terms of this analysis because they touch on topics that affect cultural heritage.

Principle 2 (Environmental and Social Assessment) outlines the requirement for the proponent to conduct an assessment to address relevant environmental and social risks and impacts of the proposed project as well as to outline steps to mitigate adverse project effects. This assessment typically takes the form of an environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) report and includes a summary of cultural-heritage baseline conditions and an effects assessment.

Principle 3 (Applicable Environmental and Social Standards) outlines the requirement to comply with relevant host-country laws, regulations, and permits that pertain to environmental and social issues. For jurisdictions where the effectiveness and application of host-country laws and regulations may not be adequate to mitigate project risk and ensure responsible project financing, the applicable IFC Performance Standards and the World Bank Group Environmental, Health, and Safety Guidelines are adopted. Guidance Notes for each of the IFC Performance Standards are not included in the EPs, but they are cited as a helpful reference when seeking guidance or interpreting the Performance Standards.

Principle 4 (Environmental and Social Management System and Equator Principles Action Plan) outlines the proponent's requirement to develop and maintain an environmental and social management system that includes provisions to manage cultural heritage resources, including implementation of a chance find management plan (see Stapp and Longenecker Reference Stapp and Longenecker2009).

Principle 5 (Stakeholder Engagement) outlines the requirement for the proponent to demonstrate effective Stakeholder Engagement as it relates to the proposed project. This is important because the IFC Performance Standards outline specific requirements for consulting with potentially affected communities on issues related to cultural heritage.

Principle 7 (Independent Review) outlines due-diligence requirements for Project Finance and Project-Related Corporate Loans. For Project Finance, third-party environmental and social consultants are required to undertake an independent review of the project assessment documentation, including the Environmental and Social Management Plans, Environmental and Social Management System, and Stakeholder Engagement process documentation to assist the EPFIs’ due diligence and assess compliance with the EPs. Similarly, for Project-Related Corporate Loans, independent review by environmental and social consultants is required for projects with potential high-risk impacts that may include significant cultural heritage.

As described above, the EPs are underpinned by IFC Performance Standards. The IFC is the World Bank's private-sector lending arm and offers investment, advisory, and asset-management services to encourage private-sector investment in developing countries that will reduce poverty and promote development. The IFC has a Policy on Social and Environmental Sustainability with eight Performance Standards and associated Guidance Notes. This Policy defines IFC clients' responsibilities for managing their environmental and social risks (IFC 2012a, 2012b). The IFC and its performance standards are meant to bridge potential gaps between the scope and effectiveness of host-country laws and regulations and internationally recognized good practices. For example, the country of Suriname lacks laws to protect cultural heritage. With respect to safeguarding cultural heritage, Performance Standard 8 (Cultural Heritage) and Performance Standard 7 (Indigenous Peoples) are the most relevant.

Performance Standard 8 defines proponent responsibilities for addressing cultural-heritage resources through the full project cycle—from planning to construction, and operation to closure. Although primarily focused on tangible heritage, it also considers fossil remains and natural features with cultural significance (e.g., sacred groves). Intangible heritage (e.g., traditional ecological knowledge) is considered if the proponent aims to use it for commercial purposes. Performance Standard 7 is largely concerned with ensuring that the development process respects the human rights, dignity, aspirations, culture, and natural-resource-based livelihoods of Indigenous Peoples, which includes safeguards for the protection of cultural heritage. Under this Performance Standard, cultural heritage is broadly defined and includes natural areas with cultural and/or spiritual value, such as sacred bodies of water and sacred rocks. See Mason (Reference Mason2012) for a detailed review and analysis of the cultural heritage provisions of IFC Performance Standards 7 and 8.

For the financial industry, salient aspects of Performance Standards 7 and 8 include the need for the project proponent to protect—and avoid adverse impacts to—significant cultural heritage in the course of project activities; comply with host-country laws and regulations; implement internationally recognized practices for the protection, field-based study, and documentation of cultural heritage; and use competent professionals.

ISO 26000

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO), in conjunction with representatives from government, NGOs, industry, consumer groups, and labor organizations, prepared ISO 26000: Social Responsibility (ISO 2010). This standard is a statement of intention and provides guidance—not requirements—on how businesses and organizations can operate in a socially responsible manner. ISO 26000 cannot be used as the basis for audits, certificates, or any type of compliance statement. Its intent is to encourage firms to go beyond mere legal compliance, demonstrate ethical and transparent behavior, and act in a manner that contributes to the overall health and welfare of society. ISO 26000 accomplishes this by defining social responsibility, translating principles into actions, and providing examples of best practices related to social responsibility. From our sample of financial institutions, Sberbank and the five Chinese banks are thought to adhere to this standard (Table 2).

Under the category of Community Involvement and Development Issue 2: Education and Culture, as it applies to actions and expectations, ISO 26000 states: “Help conserve and protect cultural heritage, especially where the organization's activities have an impact on it.” The standard also cites the following UNESCO declaration and conventions: Declaration Concerning the Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage (UNESCO 2003a), Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (UNESCO 2003b), and the Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (UNESCO 2005b; see O'Keefe and Prott [Reference O'Keefe and Prott2011] for further detail on these conventions).

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

The UN SDGs address global challenges, including those related to poverty, inequality, climate, environment, prosperity, and peace and justice. The SDGs were unanimously ratified by UN member states in 2015 and adopted as the foundation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations 2015). The framework includes 17 SDGs and 169 targets to transform the world by 2030 (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6. UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Although references to the world's cultural and natural heritage are found throughout the SDGs (see UNESCO 2018b), heritage is singled out in target 11.4—“Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world's cultural and natural heritage”—and its related indicator 11.4.1, which reads as follows:

Total expenditure (public and private) per capita spent on the preservation, protection, and conservation of all cultural and natural heritage, by type of heritage (cultural, natural, mixed, and World Heritage Centre designation), level of government (national, regional, and local/municipal), type of expenditure (operating expenditure/investment), and type of private funding (donations in kind, private non-profit sector, and sponsorship) [United Nations 2017:15].

As stated above, 24 of the banks examined in this study support the SDGs either in their entirety, or in a more selective manner, focusing on the goals and targets best aligned with their business strategy. Accordingly, sustainable development has increasingly been integrated into the guidelines, policies, and strategies of financial institutions. For example, Agricultural Bank of China (2019), Bank of America (2019b), MUFG (2019b), and Sberbank (2019b) directly invest in activities for the protection and conservation of cultural heritage. MUFG also provides indirect support for the protection and conservation of cultural heritage through staff volunteer programs at a number of World Heritage properties.

Similar to the EPs and ISO 26000, alignment of business practices with the SDGs is voluntary, but there is one important distinction. Whereas the EPs and ISO 26000 focus on project impacts, the SDGs are based around outcomes (Jenkins Reference Jenkins2019), and they provide an opportunity for financial institutions to be forward looking and proactive in their consideration of cultural heritage in their business dealings.

THE ROLE OF HERITAGE PROFESSIONALS

Using information provided in the preceding discussion, it is important to denote the role of cultural heritage practitioners in the implementation of financial-institution cultural-heritage safeguard policy. There are two main areas of intersection: (1) technical studies typically commissioned by the development proponent as a condition of project approval by a government agency and as a condition of financial support from banks or (2) retention of an external SME to review technical studies on behalf of lenders.

Technical studies commissioned by proponents can take many forms, depending on the stage of development planning and project requirements. Early-stage studies requiring heritage-resources input include the following: gap analyses, which identify the nature and scope of work that still needs to be undertaken; feasibility studies, which evaluate the technical, environmental, social, and financial aspects of a proposed project to determine if it is viable; and National Instrument 43–101 (NI 43–101) reports,Footnote 2 which govern a company's public disclosure of scientific and technical information about its mineral projects.

In those instances where a proposed project is considered viable, an assessment of environmental and social impacts is typically required to obtain host-government approval and to secure financing. These studies go by various names, including environmental assessment, ESIA, and environmental, social, and health impact assessment (see Noble Reference Noble2015). For these studies, heritage practitioners are retained to provide cultural-resources input as part of a larger team composed of environmental and social SMEs.

These studies provide a process for predicting and assessing the potential environmental and social impacts of a proposed project, evaluating alternatives, and designing appropriate mitigation, management, and monitoring measures. ESIA studies result in a publicly available document consisting of three main components: (1) a baseline (inventory) survey of environmental and social considerations (including cultural heritage); (2) an impact assessment estimating the potential effects of the project on each valued component (e.g., cultural heritage); and (3) an Environmental and Social Management Plan seeking to manage those impacts during the construction, operation, and closure phases of the project.

The baseline inventory of cultural heritage includes a desktop review of existing cultural and environmental data, consultation with potentially affected communities, and fieldwork to identify and document cultural heritage in the proposed project area. The impact assessment, also referred to as an effects assessment, combines the results of the baseline assessment and development plans to identify positive and negative project impacts on cultural heritage. Positive effects might include site discovery, advances in knowledge and understanding, or skills transfer. Negative effects are typically associated with physical impact or increased/decreased access to sites. The Environmental and Social Management Plan outlines the nature of any mitigation steps required to offset adverse effects the project may have on the environment and society, including cultural heritage. The Plan includes a Chance-Finds Discovery Protocol to address the potential for the discovery of heritage sites during the construction, operations, and closure phases of the project.

ESIAs can be completed to varying standards, with the bare minimum being the meeting of host-country requirements and, where they exist, voluntary company standards for such studies (e.g., Rio Tinto 2011). This level of assessment is typically sufficient for proponents of projects located in high-income, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countriesFootnote 3 with robust project-approval systems or in non-OECD countries where external sources of capital are not required to implement the project. In non-OECD countries where external sources of project finance are required, ESIAs are typically completed in order to meet both local and external standards such as the EPs, and they are colloquially referred to as “bankable” (Wexler Reference Wexler2008). In effect, they demonstrate that the work meets lender due-diligence requirements for financing.

Given that archaeological investigations are technical and require specialist knowledge, heritage practitioners may be retained by financial institutions as SMEs to review the cultural heritage sections of reports (e.g., ESIA, NI 43–101 reports) completed by other practitioners. Particularly sensitive projects may require a site visit and field verification of results by the heritage SME. For these assignments, the SME will be asked to evaluate the quality and adequacy of the heritage study as well as provide a statement to the effect that the work of the other party meets regulatory requirements and was undertaken with the same degree of care, skill, and diligence as would reasonably be expected from a professional qualified to perform services similar in scope, nature, and complexity.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we provided an in-depth review of business practices adopted by private-sector financial institutions for the safeguarding of cultural heritage and the ways in which these practices interface with heritage practitioners. Specifically, we examined the lending practices of 25 of the world's largest banks as they relate to cultural heritage in order to address a gap in the literature, raise awareness among heritage practitioners, explain industry motivations behind these safeguards, and identify their strengths and weaknesses.

As described above, all surveyed banks adhere to the rule of law, including heritage legislation. Similarly, each of the financial institutions examined in this article maintains an environmental- and social-policy framework for the management of environmental and societal issues in their deals. The quality of these documents varies, with the Russian and Chinese banks generally being less informative. With respect to heritage-specific sector guidelines or cross-sectoral guidelines, they are maintained by 44% of the banks and refer specifically to WHSs.

Not all banks adopt external guidance such as ISO 26000 or the EPs. Based on available information, US Bancorp, Goldman Sachs, and UBS choose not to adhere to either external standard, perhaps preferring to rely solely on their cross-sectoral guidelines (in the case of Goldman Sachs and UBS) and the strength of their reputation on matters related to environmental, social, and governance criteria. It is notable that ISO 26000 can have a role in safeguarding cultural heritage, but it has the major shortcoming in that it provides guidance only and is not a requirement. For companies that adopt ISO 26000, there are no consequences—such as decertification—for noncompliance. The EPs, with their annual public-reporting requirements (Principle 10: Reporting and Transparency), are widely adopted by the financial industry and reflect best practice.

With respect to the SDGs, their implementation is estimated to cost several trillion dollars per annum through 2030 (UBS 2019b). Obviously, there is no single pool of capital that can fund that effort, so governments and industry—including the financial industry—must play a role in achieving these goals. Given that all but one bank examined in this article align their business practices with the SDGs, a strong mandate exists for banks to take actions that support the SDGs, including the protection, conservation, and promotion of cultural heritage.

A Proposal for Banks

Based on our review and analysis of the cultural-heritage safeguard practices of private-sector financial institutions, we recommend that each bank develop and implement an Environmental and Social Policy Framework that is written in plain language and that is easily found and downloadable from company websites. Each framework should include the following:

• Recognition that host-country laws and regulations concerning cultural heritage will be followed

• Confirmation that the EPs have been adopted

• A risk policy for WHSs that includes

○ Equal treatment of natural and cultural heritage

○ Financial support for projects within WHSs only where there is endorsement from both the UNESCO World Heritage Centre and the host country's national government

○ Prohibition of investments where WHS boundaries have been adjusted (i.e., reduced) to accommodate a project footprint

• Policies that seek out and promote investments in activities that are compatible with the preservation and protection of WHSs

• Alignment of business practices with the UN's SDGs—specifically, Target 11.4 and other culture-related targets

Of the financial institutions examined in this article, HSBC and Bank of America are the closest to meeting this proposed standard.

In terms of business strategy, the protection and promotion of cultural heritage offers banks an opportunity to set themselves apart from industry peers and to enhance their reputation and brand. Whereas advocacy and corporate initiatives to support the environment (e.g., climate change, biodiversity) are widespread, similar actions in support of cultural heritage are less common. An opportunity exists, therefore, for financial institutions to “claim this space” in the marketplace by focusing on activities that promote the protection and conservation of cultural heritage. This includes implementation of strong project safeguards, the undertaking of projects aligned with the SDGs, and the creation of impact investing opportunities (UBS 2016) that aim to generate positive heritage outcomes alongside a financial return.

A Call to Heritage Practitioners

For heritage practitioners who may be called upon to provide advice, review or undertake fieldwork, and prepare studies in keeping with the private-sector bank policies and external standards described in this article, having a strong understanding of the cultural-heritage safeguards used by these financial institutions is integral to the performance of this work. This article addresses that gap in the heritage-management literature and provides the knowledge required for heritage practitioners to offer sound advice.

Looking to the future, heritage practitioners have an opportunity to apply this knowledge and promote awareness of cultural heritage and best practice among private-sector banks. Whereas cultural-heritage advocacy and education in private-sector banking has been limited, successful natural-heritage advocacy work by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) provides a roadmap for cultural-heritage professionals and organizations to consider. For example, unification of disparate interest groups under the umbrella of a registered charity with global reach and professional management will attract both the money and top talent necessary to support cultural-heritage advocacy activities similar to those achieved by the WWF. In terms of strategic alliances, none surpass private-sector banks. The table is set, and with the acceptance of the SDGs and the promise of impact investing, there is no better time to act. With this in mind, the authors hope this article will serve as a catalyst and call to action for the adoption of robust cultural-heritage safeguards and the UN's SDGs by heritage practitioners and financial institutions alike.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jeff Bailey, Ian Lilley, Fergus Maclaren, Margaret Mason, and John Welch for their insights and comments on an earlier version of this article. Global Affairs Canada played a crucial role in obtaining information on Chinese banking practices. We also thank the anonymous reviewers, as well as Oliver Obregon, who kindly prepared the Spanish abstract. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. In-kind contributions from Golder are acknowledged and greatly appreciated.

Data Availability Statement

Information concerning the cultural heritage safeguard policies of private-sector financial institutions was taken from publicly available sources with access details provided in the References Cited section of the article. The authors possess electronic copies of all cited online material.