It has long been known that many government programmes in China are implemented poorly. Policies are carried out unevenly in different areas,Footnote 1 some policies are pushed hard while others are ignored,Footnote 2 and collusion between grassroots cadres at different levels leads some initiatives to be shunted aside with few consequences.Footnote 3 But local obstruction and misconduct, along with perverse or ineffective incentives, are far from the entire story.Footnote 4 Recently, a revisionist line of research has made a case for “effective policy implementation,” where the bulk of what higher-level authorities instruct lower levels to do is achieved tolerably well.Footnote 5 But what about polices that are not blocked or carried out according to plan but instead are executed by local officials with extraordinary zeal, so that targets are exceeded by huge amounts? The Microfinance for Women (MFW) Programme was one such policy. After a slow start, the number of loans issued soared, as provincial targets were surpassed within a few months, increased by city and county authorities, and then topped again. Why was the MFW programme implemented so enthusiastically? What does the sudden acceleration in micro-lending tell us about the Chinese policy process and the role that programme design, institutional incentives, bureaucratic pressure, and local and organizational interests play in policy implementation? Finally, why, after a brief period of rapid expansion, did the ramp-up in lending stop as quickly as it had begun?

This article draws on in-depth interviews, focus group discussions and archival materials. Most of the fieldwork was conducted in Sichuan in 2012 and 2013. We interviewed 43 officials from provincial bureaus down to rural townships and urban “communities” (shequ 社区). Eight focus group discussions with recipients of MFW loans were held in Sichuan to learn how the programme was experienced on the ground. We also relied on written materials, including government regulations, internal directives, provincial statistics on MFW lending, and most importantly, annual work summaries compiled by each of Sichuan's 21 municipalities and nine provincial bureaus. To explore how closely implementation in other provinces paralleled what took place in Sichuan, we turned to media reports, government documents and national statistics. These sources allowed us to examine why the MFW programme suddenly took off and then rapidly contracted.

The Origins and Development of the MFW Programme

The MFW programme was initiated against the backdrop of the 2008 global financial crisis. With the world economy in a nosedive, the Chinese government launched a massive stimulus programme in late 2008 that pumped 4 trillion yuan (US$586 billion) into the economy. Local spending was incentivized and provincial and lower-level authorities were expected to match central outlays, which led to a proliferation of financing platforms and aggressive lending by state-owned commercial banks and other financing institutions. The stimulus generated extremely high levels of investment in real estate, infrastructure, steel, solar panels, shipbuilding and other sectors, as well as many other expansionary activities. In the early 2010s, shadow banking of various sorts also took off and lending increased dramatically.Footnote 6

As part of the central government's efforts to alleviate poverty and stimulate a sluggish economy, four ministry-level departments – the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, the People's Bank of China, and the All-China Women's Federation – jointly issued a notice in July 2009 that established a loan programme to help women start small businesses.Footnote 7 The MFW initiative had several features that distinguished it from earlier microcredit policies. First, it targeted women exclusively. Second, lending institutions were allowed to set an interest rate up to 3 per cent above a benchmark, and the central government promised to cover all interest payments, except in seven comparatively well-off provinces in south-east China.Footnote 8 Third, the All-China Women's Federation, a quasi-governmental “mass organization” (qunzhong zuzhi 群众组织) with offices in every urban neighbourhood and rural township, was designated the main unit responsible for implementing the programme. Finally, the notice instructed provincial governments to reward grassroots women's federations with bonuses if they achieved high repayment rates on the loans they issued.

The MFW programme was rolled out across China but developed slowly at first. Then, in 2012, the amount of lending soared and peaked at the end of the year. According to one internal report, 75.6 billion yuan in borrowing,Footnote 9 out of a total loan portfolio of 129.3 billion yuan, occurred in 2012 alone.Footnote 10 In 2013, the pace of lending slowed but the amount borrowed was still large, at about 51 billion yuan.Footnote 11 Women in less developed provinces displayed extraordinary enthusiasm for the programme, with loan balances in Gansu, Xinjiang, Sichuan, Henan, and Jiangxi accounting for over 55 per cent of the national total by year-end 2012.Footnote 12

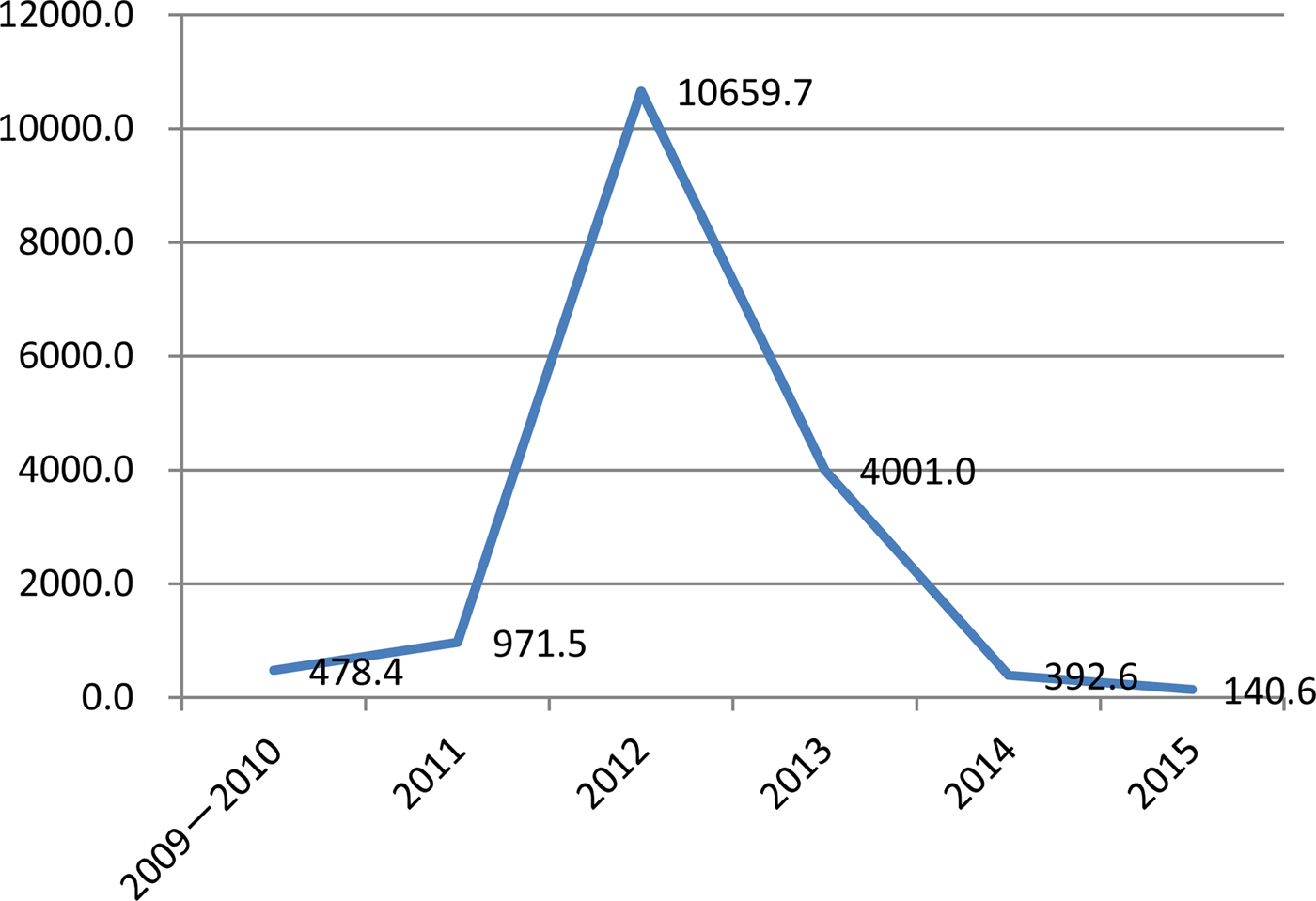

In Sichuan province, the MFW programme unfolded as it did elsewhere, although much more dramatically (see Figure 1). New loans reached 478 million yuan in 2010 and climbed to 971.5 million yuan the following year. Then a huge increase occurred in 2012, with nearly 10.66 billion yuan lent out. Finally, the MFW lending shrank, first slowly and then more rapidly. About 4 billion yuan in loans in 2013 was followed by 392.6 million yuan in 2014 and then 140.6 million yuan in 2015.

Figure 1: MFW Loans Issued in Sichuan Province, 2009–2015 (millions of yuan)

Table 1 shows how zealously local authorities in Sichuan carried out the MFW programme in 2012. All of Sichuan's 21 municipal-level governments surpassed lending goals set by the province, targets which were already many times greater than those assigned in 2011.Footnote 13 Two municipalities, Meishan 眉山 and Panzhihua 攀枝花, exceeded their targets more than tenfold, and eight municipalities issued at least four times as many loans as planned. Chengdu, the capital of the province, might appear to be a partial exception to enthusiastic implementation, insofar as it surpassed its target by a meagre 20 per cent, the smallest margin among Sichuan's 21 municipalities. But the lending level set for Chengdu in 2012 was already 20 times larger than that for the previous year, so it was hardly lax in its efforts.Footnote 14

Table 1: Implementation of the MFW Programme in Sichuan, 2012

In 2012 especially, local authorities in Sichuan were in direct competition with each other to issue more MFW loans. For example, in Bazhong 巴中 municipality, the Target Supervision Office (mubiao ducha bangongshi 目标督查办公室) regarded 100 million yuan in lending, the amount specified by the provincial government, as a bare minimum or “guarantee target” (baozheng mubiao 保证目标), and set 200 million yuan as the real goal that the city should strive to meet. In early October, however, municipal authorities suddenly raised Bazhong's target to 500 million yuan.Footnote 15 Meishan and Leshan 乐山 also saw similar increases in both expected and actual lending. By 10 November 2011, new loans in Meishan had reached 850 million yuan, an amount more than eight times the original target. But this was only the beginning: new borrowing climbed to 1.273 billion yuan less than a month later.Footnote 16 Leshan experienced an even more extreme cycle of raised targets that were soon surpassed. After lending 622 million yuan in the first ten months of 2012, more than five times the original target, Leshan's leaders decided to aim to be Sichuan's top city for MFW lending, a goal they did not quite achieve, although Leshan did reach fifth in the league ranking.Footnote 17

This rapid increase in lending in Sichuan and elsewhere raises two obvious questions. Why did local authorities implement the MFW programme with such enthusiasm in 2012? And why did the expansion in lending end?

Exceeding Ambiguous Limits: How Local Officials Exploited a Vague and Incomplete Policy

The sudden increase in MFW lending can be traced to a number of factors. One is the nature of the policy itself, in particular its vagueness and how much it left unsaid. Ambiguous provisions and silences in the founding document enabled local officials to engineer a surge in loan making by creatively interpreting collateral requirements, interest rate caps, second loan limitations, eligibility standards, and loan amounts. Although a poorly designed policy with hazy implementation guidelines did not itself cause the rapid growth in lending in 2012, it did make it possible for local leaders to expand the programme faster than anyone had anticipated.Footnote 18

Policy outcomes depend to a great extent on how individuals inside the bureaucracy interpret an initiative. To narrow the “implementation gap,”Footnote 19 policymakers often formulate highly detailed regulations and seek to leave little room for discretion by “street level bureaucrats.”Footnote 20 This was not the case with the MFW programme. The notice that instituted the policy (Document No. 72) laid out a number of broad principles but said little about important issues such as the amount of collateral required and who should provide it.

When issuing loans, collateral is usually expected. Lending institutions will typically refuse to lend to borrowers who lack assets they can seize if a loan goes sour. In government-subsidized microfinance programmes, where loans are often issued to the less well-off and the government itself may provide or waive collateral, default is common. For example, from 2005 to 2006, microfinance loans backed by Sichuan province performed poorly, with default rates exceeding 20 per cent in some municipalities. The borrowers were often not overly concerned about paying off their loans late, or indeed at all, because only the government's collateral was at risk. In the end, local authorities in Sichuan had to foot the bill for thousands of bad loans.Footnote 21

The originating document for the MFW programme said almost nothing about collateral other than that “in principle,” no collateral was required from borrowers. In practice, this meant that local governments had to backstop MFW loans with public funds, as they had with previous government-guaranteed microfinance programmes.Footnote 22 This was a powerful disincentive for local authorities, and during the first two years of the programme, only a limited amount of lending took place. By December 2010, the total loan portfolio in Sichuan, for example, was under 500 million yuan, less than half the amount envisioned when the programme began. No loans had been issued in five of Sichuan's 21 municipalities, and lending in another six added up to less than 5 million yuan.Footnote 23 Furthermore, local governments were reluctant to set up an “insurance fund” (danbao zijin 担保资金) to protect lenders when loans went bad. Even among the ten municipalities that had established a fund, MFW loans were often not guaranteed by it.Footnote 24

But if fears about taking responsibility for uncollateralized loans impeded lending in most places, some entrepreneurial officials recognized that the MFW policy's vagueness and omissions provided an opportunity to pick up the pace of making loans, rather than to be cautious. As early as 2010, local leaders in Gansu, a less well-off province in the west, pioneered the practice of accepting varied sources of collateral to back MFW loans. This produced almost instant results. By year-end 2010, while lending was languishing in most of China, the outstanding MFW loans in Gansu reached 5.16 billion yuan, or 22 per cent of the national portfolio.Footnote 25 In Sichuan, Ziyang 资阳 was the first municipality to permit collateral on a large scale to be raised from sources other than the government insurance fund. In 2010, when most Sichuan municipalities still had not issued a single loan, Ziyang's MFW lending exceeded 306 million yuan, or 64 per cent of the provincial total.Footnote 26

Raising collateral from outside the government insurance fund was not curbed or punished; instead, local innovators were praised and cited as examples to emulate. On 19 May 2011, a conference organized by the four departments that launched the initiative was held in Lanzhou, Gansu, to designate the province a national model for MFW implementation. At this meeting, the president of the All-China Women's Federation spoke highly of Gansu's performance and encouraged other provinces to learn from its experiences.Footnote 27 This was observed with great interest elsewhere and came to be seen as confirmation that non-governmental sources of collateral were permissible. Before long, the Sichuan government nominated its own MFW model, Ziyang municipality, to lead the way in Sichuan. In November 2011, ten provincial departments joined together to issue a directive on Sichuan's MFW programme. This directive explicitly encouraged local governments to be innovative and raise collateral from multiple sources. Sichuan's municipal leaders took heed and broadened their understanding of who could provide collateral. Besides the government insurance fund, third-party guarantees, property mortgages, and collateral provided by groups of women all became acceptable. Women were encouraged to ask relatives who were officials or who worked for public organizations such as schools or hospitals to guarantee loans. An official from the Sichuan Credit Union explained the (frankly sexist) thinking behind this:

Banks have limited trust in female borrowers, but they consider their relatives who hold public positions to be more reliable. Government employees are more stable and normally won't move away unless they get a promotion or are transferred to other cities. If we can't locate a borrower, we can get to these public officials. As guarantors for a relative, they should take responsibility for them.Footnote 28

Local officials throughout China came to believe that it was legal and appropriate to rely on forms of collateral other than the government insurance fund, thanks to the policy's lack of detail and the central government's acquiescence to policy entrepreneurs who wished to enlarge the programme beyond its original scope. A department chief at the Sichuan Women's Federation justified using assorted types of collateral this way: “There wasn't one single official document saying that we couldn't resort to alternative forms of collateral … Neither were we told that loans backed by mechanisms other than the government insurance fund wouldn't receive interest subsidies.”Footnote 29 A department chief from the Sichuan Bureau of Finance echoed her reasoning and explained the opening that vagueness and gaps in the policy gave implementers to explore the limits of the permissible. He reported that “although such methods for guaranteeing a loan were inconsistent with the spirit of the policy, the central government didn't say ‘No’ to these practices.”Footnote 30 An under-specified, incomplete policy allowed savvy implementers to recognize and seize an opportunity, and once they did and higher levels tacitly approved novel approaches to collateral, local innovations swiftly became national practices.

Once the collateral issue was resolved, ambiguity regarding interest rate subsidies also offered opportunities for creative misreading by local leaders who wished to expand lending. According to Document No. 72, loans made to women with interest rates no more than 3 per cent above a benchmark would have their interest paid by the central government. But, in reality, banks often issued loans at a much higher interest rate, which borrowers usually accepted because they were receiving a government subsidy, and which also allowed the banks to make more profit. For example, the interest rate for MFW loans issued by the Postal Savings Bank of China in Sichuan was 15.66 per cent in 2012. This was much higher than the 3 per cent ceiling above the benchmark, which averaged about 10 per cent that year.Footnote 31 But for local officials and bankers, there were ways to see this as consistent with earlier regulations concerning government-subsidized microfinance. One administrator at the People's Bank of China in Chengdu offered this, not entirely correct, explanation:

I think it is just a different interpretation of the policy. When the Postal Savings Bank of China was invited to join the programme, all sides agreed that the interest rate for MFW loans could be higher or lower than the benchmark. No one said that the interest rate must be lower than 3 per cent above the benchmark. Therefore, the bank assumed that a higher interest rate was allowed. The central government only had to subsidize the portion of the interest paid that corresponded with the policy, and borrowers assumed that the rest would not be covered. So the policy could be understood this way or that way.Footnote 32

The rules on repeat loans were also unclear and open to interpretation. The MFW programme was aimed at helping women who lacked resources to start small businesses, but nothing in the policy documents stated whether borrowers could receive loans with interest subsidies more than once. On 23 November 2011, officials from several Sichuan departments convened a meeting to discuss this and concluded that “qualified borrowers may receive loans with subsidies a second time.” In 2012, about 20 per cent of the provincial loan portfolio was not first loans.Footnote 33

The programme's founding document and implementing guidelines were also vague about qualifications for loan candidates, which provided yet another opening for local officials who sought to boost lending. According to Document No. 72, rural loan applicants should have followed application procedures similar to those in urban areas, but provincial authorities were given the right to determine rural borrowers’ eligibility “according to local circumstances.” For urban borrowers, there were explicit requirements that had to be met: loan applicants must have registered as unemployed with the Bureau of Human Resources and Social Security; they had to possess a certificate demonstrating that they had received re-employment training; and they also had to obtain a business licence or a certificate of membership issued by a trade union.Footnote 34 But for women in the countryside, no clear criteria existed. This absence enabled women who would not have qualified for a loan in the past to participate in the programme. Activities as ordinary as cultivating less than a hectare of land or raising livestock could be deemed “entrepreneurial.” With such low standards, “it became really hard to control lending in rural areas,” a provincial official in Sichuan's Bureau of Finance noted.Footnote 35 By 2012, 73.5 per cent of loan recipients nationally (and 66.4 per cent in Sichuan) were rural women.Footnote 36

The policy was also silent concerning the annual aggregate amount of loans that could be made in a single jurisdiction. This created substantial leeway for local officials inclined to increase the pace of lending. The director of the Yibin 宜宾 Women's Federation explained how the absence of any provisions about loan amounts made faster and faster lending possible: “What on earth is the loan limit this year? How should we interpret the directive ‘to lend what should be lent’ (yingdai jindai 应贷尽贷)? Does this mean that the central government will provide interest subsidies for all loans [no matter how big the total amount is]?”Footnote 37

Reasons to Boost Lending: Local interests, Incentives and Pressure

A policy outcome depends on how implementers act as well as on how they interpret a measure. While ambiguities and silences in the MFW policy documents provided room for manoeuvre and innovation, enthusiastic implementation was also a result of local interests, institutional incentives, and bureaucratic pressure. Local authorities could reap financial benefits and keep their superiors happy by expanding the programme, and so they were motivated to accelerate lending in 2012.

Once they had shrugged off the responsibility to guarantee microloans with their own funds, local authorities came to see MFW lending as an opportunity to stimulate the local economy and extract money from the central government.Footnote 38 In 2012, for example, 580 million yuan in MFW loans were issued in Sichuan's Bazhong municipality, which meant that borrowers in the city and surrounding counties were entitled to nearly 50 million yuan in interest subsidies from Beijing. The director of the Bazhong Women's Federation noted that this was roughly what local authorities would derive from setting up a large enterprise, with all the benefits an investment of that size would have for growth, employment and consumption.Footnote 39 An official in Gansu also pointed out that implementing the MFW programme and funnelling interest subsidies to borrowers was a comparatively easy way to get transfers from the centre to support local development.Footnote 40

In addition to the boost that interest subsidies brought to the local economy, lower-level governments also received sizable “work fees” (gongzuo jingfei 工作经费) from Beijing, which became especially appealing after the collateral issue was resolved and the 2011 Gansu conference confirmed that there was little risk in pursuing MFW lending aggressively. Earlier regulations had stated that the central government should set aside 0.5 per cent of MFW loans for personnel costs associated with the programme, although local authorities were instructed to provide matching funds (which, in the end, they often failed to do). Furthermore, provinces were required to pay bonuses to lower-level governments and women's federations that conducted lending well and had high repayment rates.Footnote 41 These provisions generated a tidy sum for local authorities who expanded the programme rapidly. In 2012, for example, the Sichuan provincial government transferred about 17 million yuan from the central government to local governments and women's federation offices in charge of implementing the MFW programme.Footnote 42

Institutional factors also made local officials eager to increase lending. As many previous studies have shown, policy implementation in China depends to a significant extent on what is listed as a “hard target” (ying zhibiao 硬指标) in the “cadre responsibility system” (ganbu guanli zerenzhi 干部管理责任制).Footnote 43 Targets were adjusted on several occasions between the founding of the programme in 2009 and the big ramp-up in 2012. MFW lending was first included in Sichuan's responsibility system in 2011 in an effort to encourage local leaders to create new jobs.Footnote 44 In 2012, MFW loans became a separate item for evaluation, which made it a harder target that could stand in the way of bonuses and promotions. After the province made this change, all of Sichuan's municipalities followed suit and quickly turned MFW lending into a hard target for lower-level cadres. With annual performance assessments at stake, and revenues from programme fees and bonuses growing, pressure to meet and exceed targets intensified. Lending goals were raised by cities and passed down level-by-level, “increasing every step of the way” (cengceng jiama 层层加码).Footnote 45 In Bazhong, the target for the municipality was disaggregated into sub-targets for each county, and county leaders had to pledge to achieve their goal by signing a responsibility contract.Footnote 46 In Nanchong 南充, the municipal Party secretary made it clear what was expected of the counties under its administration:

Nanchong is a city with a large population; thus we have great potential in carrying out the MFW policy: more people, more applicants. We have to “dive deeply into the policy” (chitou zhengce 吃透政策) and implement it well. We can't be satisfied with just fulfilling the target set by the provincial government. We must outperform our assigned task and achieve a yet higher level.Footnote 47

As the province encouraged more lending, and municipal leaders were evaluated according to how avidly they implemented the MFW policy, top city officials in Sichuan often took personal control of the programme and included it among the “No. 1 leader's projects” (yibashou gongcheng 一把手工程). For example, in Meishan, the municipal Party secretary issued six “written instructions” (pishi 批示) on the MFW programme in 2012. She also emphasized the importance of MFW lending at more than ten meetings attended by municipal leaders.Footnote 48 All county Party secretaries under Meishan were instructed on two occasions to study the policy from the vantage point of overall development of the region. She even reached out personally to a rural woman and helped her obtain a loan of 80,000 yuan.Footnote 49 Two years after the programme began, local interests, a supportive incentive structure and bureaucratic pressure had pushed the MFW programme up the list of local priorities in Sichuan and elsewhere. Almost all of the Sichuan officials we interviewed mentioned that the surge of lending in 2012 occurred in no small part because governments at all levels attached importance to implementing the programme.

In the midst of this high-level attention and pressure, most municipalities in Sichuan came up with their own strategies to speed up lending. In Bazhong, all involved departments were told to simplify MFW application procedures. Screening of borrowers was reduced or even cancelled. Local banks were required by municipal leaders to add staff for processing MFW applications: every loan counter was expected to have three rotating teams of employees on hand at all times to ensure that “stamps don't stop even when people are taking a break” (ren ting zhang bu xie 人停章不歇). Prior to the upsurge, interest subsidies from Beijing were often delayed, because loans were reported from below and central funds arrived much later. In Yibin, in an effort to encourage more lending, counties that were granted “enlarged authority” (kuoquan xian 扩权县) were required to pay subsides up front to reassure both banks and borrowers.Footnote 50 In Nanchong, municipal and county-level governments disbursed over 15 million yuan in advance to cover subsidies that would arrive later from the central government. To spur even more lending, many municipalities also encouraged competition among counties with monthly assessments, publication of poor performance by laggards, and sanctions for perpetual under-performers.Footnote 51

At the peak of the high tide in 2012, municipal and county leaders required that all organizations involved in MFW lending cooperate and show support for the acceleration of lending. An official of the People's Bank of China in Chengdu described the intense pressure felt by lending officers in Sichuan:

Officials of a bank in Meishan reported to me the pressure they faced many times. The municipal government first assigned the bank the job of loaning out 100 million yuan, and then suddenly increased it to one billion yuan. They called me for advice, but ultimately they had to carry out the task they were assigned.Footnote 52

Reasonable suggestions about proceeding at a measured pace were often equated with being unsupportive. One women's federation leader in Yibin complained:

We were required to speed up the tempo of lending. What could we do? The target had been set and we were given the task of fulfilling it. We had to catch up … But from my vantage point, I opposed such a rush. I think the programme should have been carried out step-by-step and in accordance with rules. We believed that women's demands for loans should be fostered over the long term, not in a month or two. But such suggestions were criticized back then.Footnote 53

The Role of the Women's Federation

Although programme design and incentives are crucial, “what actually is delivered or provided under the aegis of a policy depends finally on the individual at the end of the line.”Footnote 54 The structure, capacity and interests of the organization that is assigned to execute a policy shape how it is carried out.

The Women's Federation was designated the lead implementer for the MFW programme. According to Document No. 72, borrowers had to apply to the Women's Federation for a loan. The federation then investigated an applicant's qualifications and made a recommendation to banks and credit cooperatives. The Bureau of Human Resources and Social Security and the lending institution were also supposed to evaluate applicants, but during the implementation high tide these procedures were simplified or even cancelled, and recommendations from the Women's Federation carried the day. The Women's Federation was also responsible for assisting lending institutions in securing loan repayment.

The federation is a sprawling organization that has branches throughout the country. At the top sits the All-China Women's Federation. Below it there are offices in every province and municipality, and lower still there are branches in urban districts and “neighbourhoods” (jiedao 街道), as well as rural counties and townships. Even villages and urban communities have women's congresses, which serve as de facto federation branches and manage women's affairs at the grassroots.

Owing to its pervasiveness, the federation is well-positioned to mobilize Chinese women. Chen Zhili 陈至立, then president of the Women's Federation, emphasized the organization's ability to locate applicants for MFW loans in an online chat on the 100th anniversary of International Women's Day in 2010:

Some comrades might have doubted whether the Women's Federation was capable of carrying out this project. It turns out that our cadres are very able and responsible. The federation has roots at the basic level, in the villages. So federation cadres are very familiar with what issues women face and know well who is capable of starting a business and which projects are likely to be profitable. Federation staff are pushing this project forward by “roving every street and alleyway and entering villages and households” (chuanjie zouxiang, rucun ruhu 串街走巷, 入村入户).Footnote 55

The Women's Federation exists at the periphery of state power. It is uncommon for the federation to take a leading role in a project to which local authorities attach great importance. The MFW programme provided the federation with this opportunity, particularly after local leaders started to aggressively promote loan making in 2012. The surge in lending enabled local branches to raise their organizational profile by granting them the right to call on government personnel who were normally beyond their reach. For example, the director of the Nanchong Women's Federation argued that implementing the MFW programme was a “comprehensive war” (zhengtizhan 整体战) that necessitated cooperation across multiple departments. In 2012, she organized over 30 meetings, which were attended by officials from the Bureau of Finance, the Bureau of Human Resources and Social Security, and assorted lending institutions. She also reported progress in loan making to the municipal leadership on over 20 occasions.Footnote 56 Being able to summon government cadres to meetings and having direct access to municipal leaders was a welcome development and an honour for the federation. A division head of the Sichuan Bureau of Human Resources and Social Security explained, with some disdain, how the federation exploited its position at the heart of MFW implementation: “To be frank, the Women's Federation takes the MFW programme as its primary ‘work hold’ (gongzuo zhuashou 工作抓手). For our bureau, this project is only one small portion of our daily work … But for the Women's Federation, besides the MFW programme, it only gets involved in trivial issues like divorces or domestic violence.”Footnote 57

Recognizing that the MFW programme offered an opportunity to increase their clout and take on new activities, grassroots federations threw themselves into lending. In Bazhong, especially in 2012, township and village cadres were mobilized to publicize the MFW programme and develop outreach strategies to contact rural women who might be potential borrowers.Footnote 58 In Leshan municipality, the MFW programme was designated the “No. 1 Project” (yihao gongcheng 一号工程) for the Women's Federation and lending was promoted with the slogan: “Small loans, great effect.”Footnote 59 Federation staff at all levels were drawn into making loans. Offices were instructed to stay open every day (“24/7,” in many reports) to process applications at maximum speed. Directors of women's congresses in villages were made “liaisons” (lianxi ren 联系人), and went door-to-door promoting the programme to potential entrepreneurs. They were also called upon to assist higher-level offices and lending institutions in investigating the qualifications of applicants, a job they and federation staff often did poorly owing to lack of experience in issuing loans, and because, as one Sichuan Women's Federation official explained, federations were good at mobilizing women and publicizing policies, “but didn't care much about lending issues.”Footnote 60 Finally, women's congresses and basic-level federations were expected to help borrowers file their applications and assist with other procedures, such as obtaining certificates of village residency. All these initiatives enabled women to apply for and receive loans with minimal effort and with as few trips away from home as possible.

The MFW programme helped to enhance the Women's Federation's status. It also generated financial benefits for federations, from the municipality down to the grassroots. According to the Sichuan Department of Finance, federations in Sichuan received at least 14.77 million yuan in 2012 from local governments, along with an additional 3.03 million yuan from the central government.Footnote 61 In Yibin alone, municipal authorities sent over 200,000 yuan to the municipal federation, and the city's Cuiping District 翠屏区 Women's Federation, whose budget was far smaller, received the same amount.Footnote 62 Although some lower-level federations received only 20–30 thousand yuan and federation directors complained that finance departments sometimes arbitrarily cut start-up fees and bonuses they were supposed to receive,Footnote 63 the MFW programme was a significant source of revenue for local women's federations, many of which had few other funding sources besides an annual allocation from local governments.

In sum, the MFW policy benefited some women and also the federations that administered the programme. From the province to the grassroots, women's federations used MFW lending to bolster their finances and secure a role in the policy process they had rarely enjoyed in the past. Especially in 2012, after the central government signalled it was flexible about sources of collateral and the cadre responsibility system turned lending into a hard target in many locations, the MFW programme was a boon for women's federations, both materially and organizationally.

The Expansion Ends

The sudden ramp-up of the MFW programme stopped as quickly as it began. In 2013, new lending fell from 75.6 billion yuan to 51 billion yuan. Then a rebound to 67.4 billion yuan occurred in 2014, followed by a decline to 43.4 billion yuan in 2015.Footnote 64 The figures for Sichuan were even more dramatic, with new lending in 2015 tumbling to 1.3 per cent of its 2012 level.Footnote 65 The big drop in some provinces and the plateauing or gradual reduction elsewhere occurred mainly as a result of an altered approach to interest subsidies.Footnote 66 On 1 February 2013, the All-China Women's Federation convened an urgent national meeting that concluded that tighter supervision of the MFW programme was needed. At this meeting, central officials signalled that Beijing would not provide subsidies for loans that had been issued contrary to the “spirit” of the policy, even though the repayment rate nationally was still 98 per cent.Footnote 67 Provincial authorities responded accordingly. Within two months, Sichuan's Finance Department issued a notice that required cities to examine all MFW loans and banned subsidies for high-interest loans, second loans, jumbo loans above approved limits, and loans made in the name of an entrepreneur's employees.Footnote 68 Then, in September 2013, a further disincentive to increase MFW lending was put in place: a new central regulation required that localities shoulder 25 per cent of the cost of interest subsidies.Footnote 69 The ambiguity and inducements that had allowed MFW lending to take off were fast disappearing.

In provinces where the spike in lending had been especially large, such as Sichuan and Gansu, loan making was also cut because of concerns that the programme was stoking social unrest among thousands of women who worried that interest they had paid up front would never be reimbursed. As a wave of petitioning broke out, the MFW programme was becoming a political liability for local authorities in places where lending had grown the most.Footnote 70 Women's federation staff, who received many of the complaints, sought to placate borrowers and encouraged them to be patient, but as one Sichuan Federation report put it: “More and more women have become emotionally unstable … Long delays in paying interest subsidies will affect social stability and [perceptions of] the government's reliability.”Footnote 71 In these circumstances, cutting back on MFW lending and supervising it closely was the prudent move for local authorities. A smaller, more tightly monitored programme would help contain a “stability maintenance” threat and prevent it from getting worse.

Conclusion

The immediate reason that MFW lending soared in 2012 was the relaxation of collateral requirements that shifted the risk of defaults away from local authorities. But the surge also had roots in the programme's design, institutional incentives, bureaucratic pressure, and local fiscal and organizational interests. A vague and incomplete policy offered “pioneers” opportunities to construe ambiguous and missing provisions as openings that permitted more lending.Footnote 72 As MFW loan making was turned into a hard target, and competition between municipalities intensified, it became an astute career move for local officials to expand lending. Subsidies, fees and bonuses promised to boost the local economy and fatten the coffers of local governments and women's federation branches. After the centre signalled that more loan making was desirable and local innovations were allowed to stand (and even publicized nationwide), bureaucratic pressure on implementers mounted and municipal officials found an eager partner in women's federation staff, who saw the programme as an opportunity to raise the federation's profile and take on new activities. “Wholehearted support”Footnote 73 for the MFW programme materialized because it: 1) figured heavily in the cadre assessment system; 2) increased local government revenues; 3) benefited implementers; and 4) could be carried out with existing resources through institutional mobilization. But then the expansion ended as quickly as it had begun. Reduced subsidies and concerns that the programme was stoking instability cooled the “implementation fever” of lower-level governments and women's federations, both of which had been pushing lending as fast as they could only months before.

Still, there remain questions about the rise and fall of policy enthusiasm. To begin with, why did local officials exceed rather than just meet the targets they were given? This was not Anna Ahlers and Gunter Schubert's “effective implementation” or Graeme Smith's “wholehearted support.”Footnote 74 Officials at all levels did more than was expected of them and took on additional work voluntarily, as provincial targets were over-fulfilled, raised by cities and counties, and then over-fulfilled again. Cadres may have had good reasons to work rather than shirk, but why overwork? Especially with a vague policy that contained few details, we might expect implementers to do what was required and no more. Money, and competition to obtain it, was certainly an important motive to over-perform. The MFW programme produced revenues that local governments did not want to miss out on. “Special projects” (zhuanxiang 专项) initiated by the centre usually come with subsidies and bonuses, and in an era when the local state in most places is being “hollowed out”Footnote 75 and many localities are becoming more dependent on transfers from above,Footnote 76 exceeding targets can be a way to generate desperately needed funds.

More research is needed on enthusiastic implementation and its consequences. What other policies have experienced it and why? Does the MFW programme tell us something about other “fevers” or other initiatives that have taken off, such as attracting investment or establishing production bases and agricultural cooperatives?Footnote 77 When “free money” is not involved, what factors generate “increases every step of the way” (cengceng jiama) and a feedback loop where enthusiastic implementation leads to raised targets and then more enthusiastic implementation? Are there important differences between sudden accelerations and over-performance from day one? As regards the MFW programme, more research (and data) is needed on the role competition between localities played and how development level and loan making were related. We have offered some evidence that poorer provinces took up the MFW programme with particular enthusiasm, but we do not have data on all 32 provinces or lending within provinces (other than Sichuan). Future studies should go beyond our focus on the overall pattern to examine differences within it.Footnote 78

Finally, for all that the surge in MFW lending says about how vague policies, institutional incentives, bureaucratic pressure and local interests can motivate officials to surpass targets, the end of the expansion reminds us that the higher-ups can shut down enthusiastic implementation when they wish to. Ambiguity and gaps in the founding documents provided opportunities for local innovation, but once the central government made its desires known, even a dash of uncertainty about whether interest subsidies would continue and who would pay them was enough to induce local authorities to slow the pace of lending. Incentives spurred lending in 2012 but could be reconfigured when instability loomed. Bureaucratic pressure to push loans out the door could be turned into warnings to be cautious. An organization on the periphery of state power could be returned to its customary role. Ultimately, the first five years of the MFW programme is a story about control as much as loss of control.

Biographical note

Yanhua Deng is a professor in the School of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Nanjing University, China. Her research centres on contentious politics, environmental sociology and local governance. She has published articles in The China Journal, The China Quarterly, Journal of Contemporary China, and Modern China. Her recent book is Environmental Protest in Rural China (2016).

Kevin J. O'Brien is the Alann P. Bedford Professor of Asian Studies and Political Science, and director of the Institute of East Asian Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. His research focuses on Chinese politics since 1978. His interests include policy implementation, legislative politics, village elections, popular resistance and protest policing.

Jiajian Chen is an associate professor of sociology at Sun Yat-sen University in China. His research focuses on local governance in contemporary China, especially bureaucratic organization, policy implementation, NGOs and community development.