6.1 Introduction

In perhaps one of the most memorable quotes from the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) literature, Paul Craig once commented, ‘The Eurogroup can lay good claim to being the EU body that is least understood’.Footnote 1 This does not mean that it has not played a central role in decision-making in this area since its very inception.Footnote 2 On the contrary, it is, as recognized by the Euro-area leaders, ‘at the core of the daily management of the euro area’.Footnote 3 The Eurogroup partakes in deciding ‘who gets what, when, how’, which is rightly regarded as a key feature of EMU as a policy area.Footnote 4 Accordingly, this lays bare the necessity of controls over its activities in the EMU.Footnote 5

This chapter looks at the political and legal accountability of the Eurogroup. The discussion begins with the foundations and tasks of the Eurogroup (Section 6.2). The focus then shifts to the political accountability of the Eurogroup (Section 6.3), the emphasis being on its relationship with the European Council and the Economic Dialogues with the European Parliament (Section 6.3.1). The chapter further looks at its legal accountability, in light of the relevant case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) (Section 6.3.2). The penultimate section of the chapter provides an assessment of the Eurogroup’s accountability in light of the framework laid down in the introductory chapter to this volume, namely in terms of procedural and substantive ways of delivering the normative goods of accountability (Section 6.4). Section 6.5 concludes by outlining the key features of the accountability arrangements and practices pertaining to the Eurogroup.

6.2 Foundations and Tasks

The Eurogroup is recognized in Article 137 TFEU, according to which ‘Arrangements for meetings between ministers of those Member States whose currency is the euro are laid down by the Protocol on the Euro Group’. In turn, the preamble to Protocol (No 14) on the Euro Group mentions the High Contracting Parties’ desire ‘to promote conditions for stronger economic growth in the European Union and, to that end, to develop ever-closer coordination of economic policies within the euro area’. As such, it lays down ‘special provisions for enhanced dialogue between the Member States whose currency is the euro, pending the euro becoming the currency of all Member States of the Union’.

Article 1 of the Protocol sets out the composition of the Eurogroup and the purpose of its meetings. It provides that the finance ministers of the Euro-area Member States shall meet informally, when necessary, to discuss questions related to the specific responsibilities they share with regard to the single currency.Footnote 6 The Commission shall take part in the meetings, whereas the European Central Bank (ECB) shall be invited to take part in such meetings.Footnote 7 The meetings shall be prepared by the representatives of the finance ministers of the Euro-area Member States and of the Commission. Further, Article 2 of the Protocol provides that the finance ministers of the Euro-area Member States shall elect a President for two and a half years, by a majority of those States. The post is currently held by Paschal Donohoe, who is also the finance minister of Ireland.

The real-world picture is conveyed more accurately by the Eurogroup’s webpage: the agenda and discussions for each Eurogroup meeting are prepared by its President, with the assistance of the Eurogroup Working Group (EWG),Footnote 8 the latter being composed of representatives of the Euro-area Member States of the Economic and Financial Committee (EFC), the European Commission and the ECB.Footnote 9 The EWG members elect a President for a period of two years, which may be extended. The post is currently held by Tuomas Saarenheimo, who is also Chairman of the EFC. The office of the EWG President is at the General Secretariat of the Council of the EU in Brussels. ‘The secretariat tasks in relation to the Euro Group are divided between the General Secretariat of the Council (which is in charge, beyond the assistance to the President, of logistics) and the EFC Secretariat (which is responsible for the substance).’Footnote 10

According to its webpage, ‘The Eurogroup’s discussions … cover specific euro-related matters as well as broader issues that have an impact on the fiscal, monetary and structural policies of the euro area member states. It aims to identify common challenges and find common approaches to them.’Footnote 11 Craig comments that the Eurogroup is ‘central to all major initiatives relating to the euro area, broadly conceived’ and that its role is central to EU macroeconomic planning.Footnote 12 More specifically, ‘it brokers the agreements necessary for policy to become reality; it fosters implementation through close oversight; it plays a role in ensuring that EU legislation in the financial sector is properly implemented; and it is part of the accountability mechanism in the banking union.’Footnote 13 The activities of the Eurogroup may also have an impact on internal market issues more generally, which are not straightforwardly related to the single currency.Footnote 14

Apart from the primary EU law provisions that were set out above, there are various other provisions that confer tasks on the Eurogroup which are scattered throughout secondary EU law and even intergovernmental agreements. Space precludes a detailed exegesis of those legal provisions, such that we will only refer selectively to perhaps the most important of them. The Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance (also known as the Fiscal Compact, from its most impactful part) provides that the Eurogroup is charged with the preparation of and follow-up to the Euro Summit meetings.Footnote 15 It will be recalled that the Euro Summit brings together the Heads of State or Government of Euro-area Member States, as well as the President of the Commission and the President of the ECB, ‘to discuss questions relating to the specific responsibilities which the Contracting Parties whose currency is the euro share with regard to the single currency, other issues concerning the governance of the euro area and the rules that apply to it, and strategic orientations for the conduct of economic policies to increase convergence in the euro area’.Footnote 16 Moreover, according to ‘two-pack’ legislation, the Euro-area Member States shall submit annually a draft budgetary plan for the forthcoming year to the Commission and to the Eurogroup.Footnote 17 The Eurogroup shall discuss opinions of the Commission on the draft budgetary plans and the budgetary situation and prospects in the Euro-area as a whole on the basis of the overall assessment made by the Commission.Footnote 18 The Euro-area Member States shall further report ex ante on their public debt issuance plans to the Eurogroup and the Commission.Footnote 19

Furthermore, the Eurogroup forms part of the accountability mechanisms in the Banking Union.Footnote 20 More specifically, the Eurogroup receives a report from the ECB on the execution of its tasks in the Single Supervisory Mechanism, which shall also be presented to it by the Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB.Footnote 21 Moreover, the Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB may, at the request of the Eurogroup, be heard on the execution of its supervisory tasks, and the ECB shall reply orally or in writing to questions put to it by the Eurogroup.Footnote 22

6.3 Accountability Arrangements and Practice

6.3.1 Political Accountability

The political accountability of the Eurogroup is described as ‘thin’.Footnote 23 Craig comments that:

Its principal political accountability runs to the European Council, as attested to by its role in preparing Euro Area Summits and having the responsibility for ensuring that the recommendations from such meetings are followed up. The reality is, however, … that the Eurogroup has considerable power in shaping macroeconomic policy broadly conceived for euro‐area states. The recommendations that emanate from the European Council will often be at a relatively abstract level, and it will be the Eurogroup that imbues them with greater policy specificity.Footnote 24

The latter case is exemplified by the Eurogroup’s actions during and in response to the COVID-19 crisis.Footnote 25 Overall, ‘[t]here is little by way of formal accountability for the Eurogroup’s input into the Euro Summits, and equally little by way of accountability check as to how it implements Euro Summit policy, more especially when the conclusions from such Summits require interpretation and choice in the implementation.’Footnote 26 This does not, however, preclude the possibility that the Eurogroup may be ‘held to account in the European Council for the more detailed policy initiatives that the Eurogroup embraces when fulfilling European Council policy recommendations’.Footnote 27

This answers the question of whom account is to be (primarily) rendered to, but does not speak of the standards against which its performance is to be assessed. After all, the Protocol on the Eurogroup merely provides that its main task is to ensure close coordination of economic policies among the Euro-area Member States, in order to promote conditions for stronger economic growth.Footnote 28 It is rightly argued that a meaningful accountability relationship

is more difficult to achieve where the criteria against which the Eurogroup is being judged are relatively abstract recommendations from the European Council; where it is intended that these should be fleshed out by the Eurogroup; where all institutional players are mindful of the difficult political and economic determinations that have to be made; and where evaluation of success or failure may be difficult, and may not be apparent for some considerable time.Footnote 29

The Eurogroup’s role during the Euro-crisis, notably with regard to financial assistance programmes, provides a good illustration of this.Footnote 30 ‘The [Eurogroup] was the body coordinating and, de facto, deciding whether financial assistance would be granted, and under which conditions, to a requesting Euro Area Member State. It is again gaining specific relevance in the context of the Recovery and Resilience Facility.’Footnote 31 The Eurogroup assesses the national implementation of the Euro-area recommendation through national recovery and resilience plans.Footnote 32 It is also evolved in coordinating the implementation of these plans.Footnote 33

The ‘six-pack’ and ‘two-pack’ of EU legislation further make provision for Economic Dialogues.Footnote 34 Economic Dialogues are held in order to enhance the dialogue between the EU institutions on the application of economic governance rules and with Member States, if appropriate, and to ensure greater transparency and accountability. The competent committee of the European Parliament, that is, the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs (ECON), may invite representatives of Member States, the European Commission, the President of the Council, the President of the European Council and the President of the Eurogroup, to discuss economic and policy issues.Footnote 35 According to the relevant EU rules, the competent committee of the European Parliament may invite the President of the Eurogroup for an Economic Dialogue during certain stages of the implementation of the European Semester for economic policy coordination and in the context of macroeconomic adjustment programmes, including the post-programme surveillance phase.Footnote 36 It should be stressed that, under the existing rules, the European Parliament has no powers to ‘sanction’ the Eurogroup for its performance or to amend any of the decisions taken. The relevant provisions instead focus on the information and debate stages of accountability.Footnote 37 There is further the expectation that finance ministers participating in the Eurogroup will be held separately to account by their respective national parliaments, in accordance with national constitutional requirements.

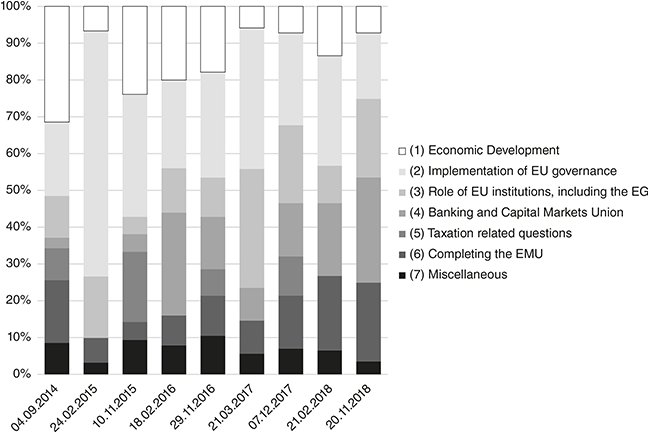

The Eurogroup President takes part in an Economic Dialogue twice a year (in spring and in autumn) and, if needed, on an ad hoc basis. This practice was agreed during the 7th legislative term through an exchange of letters between the competent Committee and the Eurogroup President.Footnote 38 Nine dialogues were held with the President of the Eurogroup in the ECON Committee during the 8th legislative term (autumn 2014 to spring 2019). Furthermore, the President of the Eurogroup occasionally participated in an exchange of views in plenary as well as in interparliamentary meetings relating to economic governance.Footnote 39 The Economic Governance Support Unit (EGOV) of the European Parliament provided members of the ECON a briefing in advance of these dialogues, as well as papers written by external experts.Footnote 40 This is important from the perspective of substantive accountability, because it helps address any information asymmetries between the European Parliament and the Eurogroup.Footnote 41 Five economic dialogues with the President of the Eurogroup have taken place thus far during the current (9th) legislative term.Footnote 42 In contrast to previous practice where only web streaming was available, a transcript of the dialogues is now made available to the public.Footnote 43

In line with agreed practices, the following procedure is applied for the exchanges of views with the Eurogroup President. First, there are introductory remarks by the Eurogroup President for about ten minutes. These are followed by five-minute question-and-answer slots, with the possibility of a follow-up question, time permitting, within the same slot. Two minutes maximum are allocated for the question, and then three minutes maximum for the answer. In the first round of questions, each political group has one slot. Thereafter, the d’Hondt system is applied, which determines the order of questions by political groups. Any time for additional slots is allocated on a catch-the-eye basis.

Overall, the MEPs ask well-informed questions. In terms of the topics discussed, these are very much the issues of the day (whether it is, for example, financial assistance programmes back in the day or, nowadays, the assessment of recovery and resilience plans or the future of the EU fiscal rules). The MEPs also address structural issues pertaining to the EMU architecture, such as the completion of the Banking Union. Obviously, these two sets of issues sometimes intersect (as was the case, for example, with questions regarding the postponement of the work plan for the Banking Union). Further, there are questions about the Capital Markets Union, the digital euro, the enlargement of the Euro-area, as well as plenty of other issues. Whenever questions are not (adequately) answered by the Eurogroup President, it is common for the MEPs to return to the point made by their colleagues previously.Footnote 44 It is clear that the questions asked focus not only on the procedure by means of which a particular decision or policy choice was made but also on the substantive worth of the policy decision itself.Footnote 45

The Economic Governance Support Unit has conducted an extensive analysis of the Economic Dialogues with the President of the Eurogroup during the 8th legislative term (autumn 2014 to spring 2019). Nine dialogues were held in ECON during the said period. ‘As a general conclusion, one can say that issues raised during the dialogues reflected on-going policy work by the Eurogroup and other topical issues related to the well-functioning of the euro area, including the public attention given to a specific policy issue at the time of the dialogue.’Footnote 46 The following figure provides an overview of the topics discussed during the 8th legislative term.

The Economic Dialogues with the Eurogroup President are rife with comments on accountability.Footnote 47 It is clear that the European Parliament, and the ECON Committee in specific, wants more on part of the Eurogroup in terms of accountability and transparency. Moreover, it is clear that the MEPs take issue with the frequency of those meetings with the Eurogroup President.Footnote 48 The Chair of the ECON Committee, Irene Tinagli, has opened the first two Dialogues with Eurogroup President Paschal Donohoe with an, to all intents and purposes, identical remark:

President Donohoe, we were very pleased to read in your motivation letter as candidate for the Eurogroup President that, and I quote you: ‘effectively communicating to our citizens and to the European Parliament the steps we are taking in the euro area will be a priority of my term’. So I would like to take this opportunity to reiterate ECON’s request for enhanced cooperation with yourself and with the Eurogroup, and invite you to put forward how you would like to follow up on these. Due to the key role of the Eurogroup in steering the policy work of the euro area as a whole, we would like to stress the importance of a well-established cooperation practice with the European Parliament, notably our Committee. One way would be to go in the direction of the practice that we have for the monetary dialogue with the ECB President, which has been working very nicely in enhancing our cooperation. In these very challenging times, the Eurogroup is indeed at a key position. Therefore I think that the need for transparency and accountability is particularly important for us.Footnote 49

The Eurogroup President replied, on the second occasion that this comment was made, thus: ‘I’ll certainly reflect on what the Chair just said there regarding how we can structure our dialogue in the future.’ Overall, strengthening the (political) accountability of the Eurogroup remains work in progress. This places added emphasis on its legal accountability, which, as seen in the following section, is – at best – scant and indirect.Footnote 50

6.3.2 Legal Accountability

The legal accountability of the Eurogroup has been the subject of lengthy litigation before the EU courts and remained ill-defined for a number of years. The leading authorities are Mallis and Chrysostomides. In very simple terms, it was held in Mallis that litigants cannot admissibly bring actions for annulment under Article 263 TFEU against the acts of the Eurogroup.Footnote 51 The Court noted that the term ‘informally’ is used in Protocol (No 14) on the Euro Group and that the Eurogroup is not a configuration of the Council pursuant to the latter’s Rules of Procedure. Accordingly, it could not be equated with a configuration of the Council or be classified as a body, office or agency of the EU within the meaning of Article 263 TFEU.Footnote 52

In Chrysostomides, the Court held that the Eurogroup is not an ‘institution’ within the meaning of the second paragraph of Article 340 TFEU, such that its actions cannot trigger the non-contractual liability of the Union.Footnote 53 What renders this judgment uniquely important for the accountability of the Eurogroup is the reasoning provided by the Court for its judgment denying that the Eurogroup is an EU entity established by the Treaties. The Court held that ‘the Euro Group was created as an intergovernmental body – outside the institutional framework of the European Union’ and that ‘Article 137 TFEU and Protocol No 14 … did not alter its intergovernmental nature in the slightest’.Footnote 54 The Court further held that ‘the Euro Group is characterized by its informality, which … can be explained by the purpose pursued by its creation of endowing economic and monetary union with an instrument of intergovernmental coordination but without affecting the role of the Council – which is the fulcrum of the European Union’s decision-making process in economic matters – or the independence of the ECB’.Footnote 55 It also held that

the Euro Group does not have any competence of its own in the EU legal order, as Article 1 of Protocol No 14 merely states that its meetings are to take place, when necessary, to discuss questions related to the specific responsibilities that the ministers of the [Member States whose currency is the euro] share with regard to the single currency – responsibilities which they owe solely on account of their competence at national level.Footnote 56

As argued extensively elsewhere, the Court’s reasoning in Chrysostomides is unconvincing.Footnote 57 First, it is not adequately explained in the judgment why Article 137 TFEU and Protocol No 14 did not alter the Eurogroup’s intergovernmental nature in the slightest. Insofar as the Court refers selectively to arguments provided by the Advocate General, notably his literal and teleological interpretation, this interpretation of the provisions of the Protocol is not straightforward in textual terms, and that whatever the origins of the Eurogroup and its functions prior to the Treaty of Lisbon may have been, they do not seem to warrant the conclusion that, following the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon, the Eurogroup remains an entity situated outside the EU legal and institutional framework. Second, it is not clear from the judgment why the informal nature of the Eurogroup means that it is not an EU entity established by the Treaties for the purposes of non-contractual liability. In reality, formally recognizing the Eurogroup by means of primary law provisions would not affect the role of the Council, insofar as those Treaty provisions which confer powers on the Council remained unchanged. It is perfectly possible to recognize the existence of an entity within the EU institutional framework which would not encroach on the powers of the Council. It is also unclear why the informal nature of the Eurogroup is necessary to preserve the ECB’s independence. Third, contrary to what the Court stated, we have seen that various EU law provisions confer powers on the Eurogroup. This also prompts the question of whether secondary EU law may confer powers or tasks on informal, non-EU bodies, especially to the point of involving them in the accountability mechanisms for a formal EU institution, the ECB.

According to the Court in Chrysostomides, individuals may bring before the EU courts an action to establish non-contractual liability of the EU against the Council, the Commission and the ECB in respect of the acts or conduct that those EU institutions adopt following the political agreements concluded within the Eurogroup.Footnote 58 Moreover, the principle established in Ledra Advertising applies,Footnote 59 meaning that an action for damages is admissible insofar as it is directed against the Commission and the ECB on account of their alleged unlawful conduct at the time of the negotiation and signing of the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the European Stability Mechanism (ESM).Footnote 60 Furthermore, the Court extended the Ledra principle to the participation of the Commission in the activities of the Eurogroup. It held that

the Commission … retains, in the context of its participation in the activities of the Euro Group, its role of guardian of the Treaties. It follows that any failure on its part to check that the political agreements concluded within the Euro Group are in conformity with EU law is liable to result in non-contractual liability of the European Union being invoked under the second paragraph of Article 340 TFEU.Footnote 61

The Court is effectively arguing that there is a complete system of remedies and procedures, such that litigants in this area are ensured effective judicial protection. Unfortunately, this is most certainly not the case when the agreements reached in the Eurogroup are implemented by non-EU bodies, such as is the case when the MoU with the ESM gives concrete expression to a macroeconomic adjustment programme. The ESM Treaty, as it currently stands, gives jurisdiction to the CJEU only when an ESM Member contests the internal resolution of disputes (with another ESM Member or the ESM itself) on the interpretation and application of the ESM Treaty or the compatibility of ESM decisions with the ESM Treaty.Footnote 62 Private litigants have no standing to challenge the decisions of the ESM organs. What is more, as explained extensively elsewhere, there may be no measures adopted by formal EU institutions incorporating the specific harmful measures that litigants wish to challenge.Footnote 63 The relevant Council Decision, whether adopted on the basis of Articles 136(1) and 126(6) TFEU as was the case in Chrysostomides or – nowadays – on the basis of ‘two-pack’ legislation,Footnote 64 may not include all the terms from the Eurogroup statement and/or the MoU with the ESM. Chrysostomides is a case in point here, as only some of the harmful measures were mentioned in the impugned Council Decision. EU courts may or may not be able to read any terms that are not (fully) replicated into the relevant Council Decision.Footnote 65

It should be noted that the Court in Chrysostomides recognized, for the first time, that EU law measures (in casu, a Council Decision) that post-dated the adoption of the harmful measures by the national authorities concerned may nevertheless trigger the non-contractual liability of the Union, provided that the relevant Union institution (the Council) had required the maintenance or continued implementation of the harmful measures and that the national authorities concerned had no margin of discretion to escape that requirement.Footnote 66 However, as explained elsewhere, the terms of those measures are often vague, such that the national authorities concerned have a margin of discretion for the purpose of laying down the impugned rules.Footnote 67 Chrysostomides is again a case in point, and the actions for damages were declared inadmissible insofar as they were directed against the relevant Council Decision. The extension of the Ledra principle to the Commission’s participation in the activities of the Eurogroup may appear more promising, but, as argued elsewhere, its scope of application remains uncertain.Footnote 68 It seems that the Commission retains its role of guardian of the Treaties as regards all the activities of the Eurogroup, such that any failure on its part to check that (any of) the political agreements concluded within the Eurogroup are in conformity with EU law may give rise to non-contractual liability of the Union. This is a much broader scope of application for the Ledra principle than the financial assistance context in which it was first elaborated. Further, it is not clear what the Commission should do if, according to its assessment, a political agreement concluded within the Eurogroup is not in conformity with EU law.

6.4 An Assessment of the Eurogroup’s Accountability

The status quo with regard to the accountability of the Eurogroup is probably problematic by any standards. This is rather self-evident, especially if one were to apply national accountability benchmarks to EMU and look into any shortcomings that might exist in their institutionalization at the EU level, notably as regards the role of parliaments but also courts (thereby following a deductive approach, as per Akbik and Dawson).Footnote 69 It is equally true in case standards of accountable behaviour that are inferred from the EU’s Treaty framework are applied to the Eurogroup (which would constitute an inductive approach, according to Akbik and Dawson).Footnote 70 The latter case is exemplified by the transparency arrangements pertaining to the Eurogroup, as well as the judicial protection accorded to individuals affected by its actions, especially after Mallis and Chrysostomides.

To be sure, there is considerable disagreement among scholars with regard to accountability, not only in the specific area of EMU, but also with regard to the EU in general. This disagreement normally centres on four dimensions which frame the accountability discourse.

There is significant divergence of view at the normative level as to the framework against which EU accountability should be judged. There can be real dispute as to what the positive rules prescribe, which can shape different conclusions as to whether the normative vision is properly reflected in those rules. There are differences yet again at the empirical level, as to whether the legal rules, given their natural textual interpretation, capture the reality of how the institutions operate in practice, with consequential implications for assessment of accountability. Temporal change can, moreover, impact radically on the powers possessed by a particular institution, with consequential implications for the suitability and efficacy of accountability mechanisms.Footnote 71

Notwithstanding any disagreements between scholars, it may be disputed whether academic discourse about accountability in EMU is ‘at a stalemate’.Footnote 72 This is so, notwithstanding the fact that there could be said to be ‘a gap between what is seen as necessary and what is feasible in the EMU governance framework’.Footnote 73 For the avoidance of any doubt, the framework introduced by Akbik and Dawson in the introductory chapter to this volume is extremely valuable in analysing the accountability discourse on EMU and in evaluating the existing arrangements as well as their practical application, also beyond the confines of EMU for that matter. It is no coincidence that it is also utilized in this chapter. However, it seems that it is principally the politics of EMU that have reached a stalemate. Enhancing the accountability and transparency arrangements in the EMU is seemingly not on the agenda. It does not appear to be a (top) priority. This could be said to be explained by the fact that national leaders and EU institutions often had to respond swiftly to the various crises that the EU has faced in the past decade. However, this would not explain away the fact that, after all these years, there is no concrete plan to enhance accountability and transparency in the workings of EMU. Nor is there yet a ‘grand plan’ for enhancing accountability and transparency in a reformed (or deepened) EMU either. It has been argued elsewhere that:

high-level reports on EMU reform only discuss accountability as an afterthought. The relevant section in those reports often conflates different issues, thereby mixing accountability with concepts and issues such as: transparency; national ownership; effective implementation; institutional reform more broadly conceived; and the external representation of EMU. We do not yet have a ‘grand design’ for enhancing accountability in a deep and genuine EMU. Instead, one has to trawl through the documents accompanying the Commission’s Roadmap to get a glimpse of the accountability (and transparency) arrangements that would obtain in a reformed EMU.Footnote 74

This remains true, in my opinion, to this day. This is so, notwithstanding the limited improvements that were made when the EU’s recovery plan was introduced.Footnote 75

It could be said to be true that we should not expect the EU institutions to produce such a plan, as this would not be in the interests of those controlled and assessed.Footnote 76 Nevertheless, this approach entails ‘pay-offs and trade-offs’. On the one hand, it obviates the need for Treaty revision and various amendments to secondary law, and avoids any difficult interinstitutional conflicts and/or discussions between the Member States. On the other hand, it is doubtful whether the existing accountability arrangements in the area of EMU are enough ‘to provide a democratic means to monitor and control government conduct, for preventing the development of concentrations of power, and to enhance the learning capacity and effectiveness of public administration’.Footnote 77 At a broader level, it is doubtful whether they ‘can help to ensure that the legitimacy of governance remains intact or is increased’.Footnote 78 As shown in this chapter, this is all the more true in the case of the Eurogroup.

As regards the EMU, the predominance of procedural ways of providing the normative goods of accountability, identified in the introductory chapter to this volume, viz. openness, non-arbitrariness, effectiveness and publicness,Footnote 79 is not fortuitous. Take the first normative good of accountability, for example, openness. ‘We might … want accountability because we see it as a device to ensure that public action is open, transparent, and contestable.’Footnote 80 In the EMU, it is often the case that either the relevant procedures for gaining access to information and documents do not exist at all or that they are found wanting.Footnote 81 In which case, it is only natural that the debate principally focuses on having the right procedures in place, which is a step logically prior to regularly probing and contesting official action.Footnote 82 To be sure, the debate should not stop there, and the accountability holders concerned should use the information and documents provided to regularly probe and contest the conduct of the ‘EMU executive’. Nevertheless, it remains the case that accountability holders (and the general public) first have to exert considerable energy to pierce the veil of secrecy or non-transparency behind which the work of the ‘EMU executive’ is sometimes carried out.

The very body that forms the subject matter of this chapter provides a fine example of this, notably as regards the lack of transparency of Eurogroup meetings and requests for public access to Eurogroup documents. Nevertheless, the 2016 Transparency Initiative by the Eurogroup President has covered some ground. More specifically, in the Eurogroup meeting of 11 February 2016, ‘Ministers agreed as a first step to make public the annotated agendas for Eurogroup meetings and the summaries of their discussions’.Footnote 83 Moreover, the Eurogroup decided on 7 March 2016 that ‘in future, Eurogroup meeting documents would be published shortly after the meetings … unless the institutions which drafted them object’.Footnote 84 ‘Documents which have not been finalised or which contain market-sensitive information will not be made public.’Footnote 85 The European Ombudsman Emily O’Reilly notes that transparency is ‘an issue of prime importance for further legitimacy and public trust’ and has asked the Eurogroup President to make further improvements as regards access to documents relating to the work of the Eurogroup that are not published proactively; transparency in the workings of bodies and services that prepare Eurogroup meetings and notably in the EWG (notices and provisional agendas of meetings); and the publication of draft programme country-related documents prior to Eurogroup meetings.Footnote 86 However, Jeroen Dijsselbloem, then President of the Eurogroup, expressed the view that the Eurogroup is not a Union institution, body, office or agency, such that neither Article 15(3) TFEU and Article 42 of the EU Charter nor Regulation 1049/2001 applies to it.Footnote 87 He nevertheless noted, ‘Despite these legal considerations, the Eurogroup’s recent initiatives respond to perceived shortcomings in transparency and reflect the political will to adhere to the principles stated in Article 15(3) TFEU and Regulation 1049/2001.’Footnote 88 In his response to the Ombudsman letters, the Eurogroup President highlighted the need to protect the internal discussions that take place in the EWG to prepare the Eurogroup at technical level, whilst emphasizing that the Eurogroup’s proactive transparency regime in principle applies to all documents on which the political debate in the Eurogroup is based.Footnote 89 Further, he noted that the publication of programme documentation prior to the Eurogroup meetings was not deemed appropriate by the Eurogroup since they can be subject to change and are part of a negotiation process.Footnote 90 It may be observed that it is hard to separate ‘technical’ from ‘political’ aspects with regard to MoU conditionality. Moreover, the provision of programme-related documents in a sufficiently timely manner is crucial so that they be used by accountability fora in their scrutiny of the activities of the ‘EMU executive’.Footnote 91

The most recent developments regarding transparency in the work of the Eurogroup and its satellite bodies are as follows. The previous Eurogroup President, Mário Centeno, informed ministers at the Eurogroup meeting held on 7 September 2018 of his intention to review the transparency initiative adopted by the Eurogroup in 2016 and consider further improvements.Footnote 92 In her letter to the Eurogroup President dated 13 May 2019, the European Ombudsman noted, ‘One outstanding matter is the transparency of the bodies involved in preparing Eurogroup meetings, in particular the Eurogroup Working Group.’Footnote 93 The European Ombudsman has launched a strategic inquiry into how requests for public access to documents of the Eurogroup, the EWG, the EFC and the Economic Policy Committee have been handled by the Council and the Commission under the EU rules on public access to documents. She further welcomed the Eurogroup President’s views ‘on the possibility of adopting a more ambitious approach to the transparency of the EWG, extending for example to the proactive publication of EWG meeting documents’.Footnote 94 In response to this as well as other calls,Footnote 95 the Euro-area finance ministers agreed in September 2019 ‘on some additional proposals to increase transparency … while paying particular attention to respect the requirement of confidentiality of the Eurogroup’.Footnote 96 These include improving the EWG webpage by providing more information, publishing the EWG’s calendar meeting, expanding Eurogroup summing-up letters where relevant, bringing forward the publication of the draft Eurogroup (non-annotated) agenda, creating an online repository of publicly available Eurogroup documents, and providing more information on the Eurogroup’s webpage on how the right of access to documents may be exercised with respect to documents held by other EU institutions.Footnote 97 These are by no means cosmetic changes, and the Eurogroup and its members are to be commended for introducing them. Whether this meets the higher demands that substantive openness would place on the Eurogroup and its accountability holders is up for debate.Footnote 98 Furthermore, it is not a foregone conclusion that the other ‘accountability goods’ are also delivered, such that it may be contested whether certain Eurogroup decisions are not arbitrary, are effective, and/or are taken in the public interest.Footnote 99

Last, as regards the Eurogroup’s legal accountability, there is no question whether there is a predominance of procedural accountability or whether there is a clearer need for more substantive accountability, because the acts and conduct of the Eurogroup are simply not subject to review by the CJEU. We have seen that the rulings in Mallis and Chrysostomides have rendered the Eurogroup immune to two key judicial accountability mechanisms in the Treaties, viz. actions for annulment and actions for damages. What is more, the Chrystostomides ruling might have wider ramifications for the application of EU rules to the Eurogroup. The reasons provided by the Court for its judgment could be seen to lend credence to arguments that the EU’s transparency regime does not apply to the Eurogroup, examined supra in this chapter with respect to access to documents.

6.5 Conclusion

The preceding discussion has illustrated that the Eurogroup is an informal body with a vague mandate, which exercises an increasing amount of executive power. It is not, however, subject to the accountability checks that exist when executive power is exercised by the Commission or by the formal Council configurations.Footnote 100 Its principal political responsibility runs to the European Council, but there is little by way of accountability checks as to its input into European Council/Euro Summit meetings and the manner in which it follows up on the recommendations from such meetings. Further, there is certainly scope to improve the Eurogroup’s interactions with the European Parliament, not least in the eyes of the MEPs themselves. As regards legal accountability, we have seen that actions for annulment may not be brought admissibly against the acts of the Eurogroup, and that the CJEU cannot hear a claim for compensation that is directed against the EU and based on the unlawfulness of an act or conduct the author of which is the Eurogroup. The remaining avenues for judicial review are insufficient to ensure that litigants are accorded effective judicial protection in this area.

Ultimately, the Eurogroup’s accountability regime is currently stuck somewhere on the road between procedural and substantive accountability, with various improvements made over the years (following considerable pressure exerted by other institutions and actors), but also crucial preconditions for more robust accountability mechanisms missing altogether. Strengthening the accountability of the Eurogroup in EU fiscal and economic governance, as well as of the ‘EMU executive’ more broadly, remains work in progress. However, it is seemingly not accorded the political priority that it ought to be given in the various reform plans and blueprints. What is more, if it is indeed the case that the Eurogroup is a non-EU entity (as per Chrysostomides), some key changes to its accountability and transparency may no longer be possible within the framework of the existing EU Treaties.