Introduction

Over the last decade or so, populist parties have become increasingly successful, both in Europe and beyond. While there is disagreement in scholarly and public debates, most agree that populist parties invoke a vision of society as deeply divided between two groups: the virtuous, ordinary, or common ‘people’; and a self-interested or corrupt ‘elite’.Footnote 1 The rise of populist parties is novel in several respects. Their increasing success has profoundly altered the structure of political competition in many European countries. Populists win many votes, have become major parties of opposition, and often participate in government, sometimes as junior coalition partners, other times playing leading roles. These increasingly powerful parties operate in a globalised, interdependent Europe, which provides both opportunities and constraints. It is difficult to draw straightforward analogies with the interwar rise of fascism and post-war communist takeover in Eastern Europe though. While fascist and Marxist-Leninist revolutionaries pitched themselves clearly in opposition to liberal democracy, the democratic orientation of populism is much more ambiguous. Populist would-be-autocrats often legitimate rule with appeals to popular sovereignty in regular if not always ‘fair’ electoral contests. In some cases, populist anti-elitist appeals may help unseat governing cliques that are in fact unresponsive or corrupt. This uncertainty is reflected in the academic literature, where some see populism as a path to ‘true’ democracy, while for others it as a road to dictatorship, or some kind of hybrid, illiberal democracy.Footnote 2

Despite this ambiguity, opposition to populist parties is often pitched in the language of democratic defence. Yet, as I spell out below, populist success with voting publics, their claims to put ordinary people first, and their entry into government shake confidence in the utility of the scholarly paradigms of ‘militant democracy’ or ‘democratic defence’, which have long shaped public policy and scholarship on how liberal democrats ought to respond to challengers. These traditional approaches are shaped by interwar experience of the Nazi’s rise to power, and the rise of right-wing populist parties in Europe from the 1980s. They have tended to contemplate responses to relatively minor parties of opposition or those with relatively clear anti-democratic or illiberal ideologies. These shortcomings require the development of a new conceptual language to better understand the nature, political effects, and normative implications of opposition to contemporary populist parties. As a first step in this endeavour, I present a new typology to classify what we already know about opposition to contemporary populist parties and to facilitate further empirical and comparative studies of that opposition. This typology facilitates broader reflections on the normative implications of contemporary modes of opposition with populist parties, and a conceptual rubric for understanding variation and developing new theories to evaluate the effectiveness (or otherwise) of initiatives opposing populist parties.

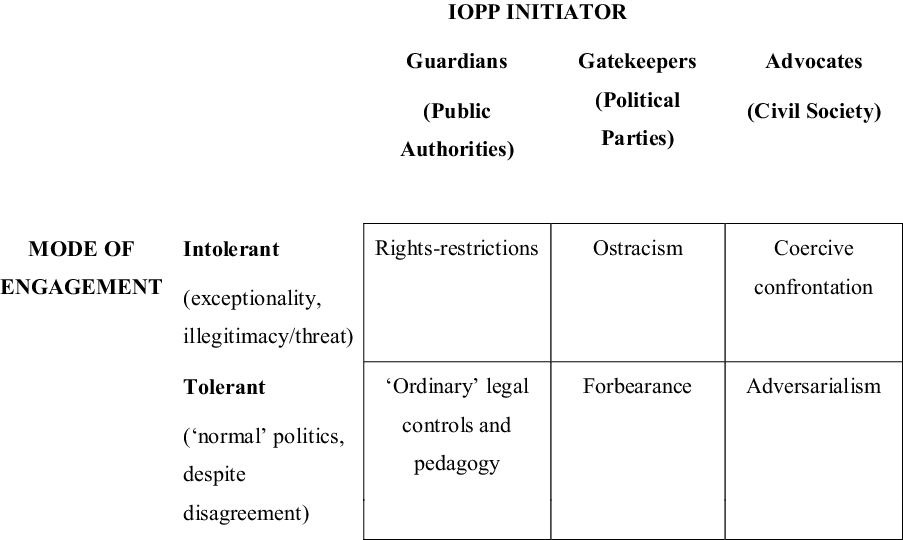

The article begins examining the extent to which existing classificatory schemes and typologies are ‘fit for purpose’. I then outline a typology for classifying what I call Initiatives opposing Populist Parties (henceforth IoPPs). First, it classifies IoPPs according to the type of political actor that initiates opposition against populists (public authorities, political parties, or civil society actors). The second classificatory criterion is more complex, focusing on whether the modes of engagement employed are ‘tolerant’ or ‘intolerant’. While my typology draws on previous work on militant democracy and democratic defence, it departs from them by allowing classification of a much larger range of initiatives, by a wider range of opposing actors, operating at and across local, national, and international territorial levels of governance. Acknowledging that populist parties are often more powerful politically than typical challengers from previous decades, and the normative challenges of navigating much muddier waters when evaluating the threat of populist parties to liberal democratic institutions, the typology is much more sensitive to what I call ‘normal politics’ initiatives. In contrast to the intolerant, exceptional measures typically of interest to the paradigm of militant democracy, such as party bans, normal politics initiatives are typically tolerant forms of engagement with populist parties similar to those used in relation to other kinds of political opponent.

Problems with militant democracy and democratic defence approaches

Over the last few decades, scholars have developed several conceptual frameworks to classify responses to anti-system parties and movements.Footnote 3 To my knowledge, there has been no attempt to develop a comprehensive classification of responses to populist parties per se.Footnote 4

Efforts to classify opposition to anti-system actors have been strongly influenced by the concept of ‘militant democracy’, whose origins are traced to Karl Loewenstein’s appeal for robust responses to fascism in 1930s Europe.Footnote 5 Militant democracy is often defined as legally-authorised, but exceptional, restrictions of certain basic political rights – particularly those of association and expression – to pre-emptively marginalise those who are otherwise acting within the law and prevent them from undermining liberal democracy.Footnote 6 During the Cold War, the principal targets of militant democracy were fascist and orthodox communist parties that participated in electoral politics despite a ‘declared… intention to replace democracy with something supposedly better’.Footnote 7 Typical measures of militant democracy were party and association bans and restrictions of free speech.

Müller argues that militant democracy is relevant for opposing populists. Short of a ‘clear and present danger’, he argues, we can recognise ‘attacks on core democratic principles’ when proponents of ‘extremist views’: (1) ‘seek permanently to exclude or disempower parts of the democratic people’; (2) ‘systematically assault the dignity of parts of the democratic people’; and (3) ‘clearly clothe themselves in the mantle of former perpetrators of ethnic cleansing or genocide’.Footnote 8 A further type occurs when ‘the proponents of extremist views’ behave in ways ‘often associated with the concept of populism’.Footnote 9 That is, when (4) ‘proponents of extremist views … seek to speak in the name of the people as a whole, systematically denying the fractures and divisions of society (in particular those associated with the contest of political parties) and systematically seek to do away with the checks and balances which have come to be associated with all European democracies created after 1945’.Footnote 10 Applying normative theories of militant democracy and the practices they justify to populist parties is far from straightforward, however. As mentioned above, it is a matter of considerable debate whether populism is a ‘threat’ or a ‘corrective’ to liberal democracy and many disagree with Müller’s characterisation of populism as a form of extremism. Against the ‘populism-as-extremism’ position, others argue that populism can in some cases be a form of radical democracy,Footnote 11 or at best a form of hybrid illiberal democracy.Footnote 12 In addition, as Rovira Kaltwasser argues, an important problem is that militant democracy ‘implicitly assumes that there is wide consensus among both the population and the elite on what democracy means and who constitutes the demos’, while the prevalence of populism reveals distinctive ‘understandings of both democracy and the boundaries of the demos’.Footnote 13 This is one reason why rights-restricting initiatives typical of militant democracy are rarely used against populist parties in contemporary Europe.

Another set of classificatory schemes focuses on a much broader range of responses. These can be loosely grouped together into a ‘defending democracy’ approach and are dominated by, but not exclusive to, political scientists.Footnote 14 Capoccia’s widely cited typology distinguishes between initiatives pursuing shorter- and longer-term goals, and between ‘exclusive-repressive’ and ‘inclusive-educational’ initiatives. Down’s typology, which principally focuses on party-political strategies, distinguishes between, on the one hand, a strategy of disengagement and engagement with parties deemed liberal democratic challengers, and more-or-less tolerant responses on the other. Similarly, Meguid and Albertazzi et al. classify party-political responses into dismissive, adversarial, and accommodative strategies of partisan competitors. Fox and Nolte build on theoretical distinctions between ‘procedural’ and ‘substantive’ models of democracy. Procedural models conceive democracy as an institutional arrangement for choosing leaders, with majority rule as the basis for legitimacy. Tolerance is a transcendent norm and there are no guarantees that democracy will always prevail. In the substantive model, democracy is conceived as a means for creating a society where citizens enjoy core rights and liberties; the model asserts that rights should not be used to abolish other rights. Similarly, Rummens and Abts’s ‘concentric containment’ model of democracy distinguishes between initiatives associated with substantive/militant and procedural conceptions of democracy on the one hand, and whether an anti-system party is politically significant enough to enter formal political institutions on the other. Malkopoulou and Norman introduce a ‘social democratic’ model of democratic defence, which they argue is superior on normative grounds to ‘militant democracy’ and a ‘liberal-procedural’ model.

These typologies differ in terms of the range of initiatives they encompass and the types of initiating political actors addressed. For example, Downs, Meguid and Albertazzi et al.’s typologies focus on the actions of political parties. Others, such as Capoccia and Pedahzur’s, classify a broader range of initiatives ranging from party bans, criminal law, lustration measures, collaboration with challenger parties in government and long-term strategies of civic education. Most typologies prioritise state-based initiatives and the strategies of political parties, although both Pedahzur and Rummens and Abts pay some attention to civil society response to anti-system parties.

Despite their many insights, these democratic defence approaches have shortcomings limiting their usefulness for studying contemporary responses to populism. Like militant democracy, most assume that the initiatives they study oppose ‘extremists’ posing a readily identifiable threat to liberal democracy. Furthermore, in these approaches opponents are predominantly opposition parties, which is at odds with the fact that so many populist parties in Europe routinely enter – and sometimes dominate – government. It is hard to see where international opposition to populist parties, such as Court of Justice of the EU rule of law judgments against Poland, or the EU’s new rule of law conditionality budget sanctions targeting Hungary, fit into any of these classificatory schemes.Footnote 15 In addition, classifications developed by political theorists are often difficult to operationalise, particularly those based on distinctions between procedural and substantive democracies.

In sum, new thinking is required to understand responses to populist parties beyond the conventional repertoire of exclusionary, repressive militant democracy, and the broader, but largely state- and party-based repertoire of democratic defence approaches. The typology outlined in the next section provides a way forward.

A new typology of initiatives opposing populist parties: democratic defence as ‘normal politics’

A core assumption underpinning the typology is that populist success means that populist politics is probably here to stay, at least for the medium term. Their popularity with voters and governing status in many European countries means many populist parties cannot simply be banned, kept in ‘quarantine’, or ignored. Those who disagree with populist parties will often need to deploy the kinds of initiatives routinely used against other politically successful opponents, such as parties of the centre-left and right. This can include deploying constitutional checks and balances constraining the power of governing parties, national and international legal constraints to block individual anti-democratic or illiberal reforms, or civil society actions organising strikes or protest in the streets. Repressive or exclusionary initiatives typically linked to the traditional paradigms of militant democracy and democratic defence are not entirely absent, as continuing efforts to ostracise National Rally in France or Alternative for Germany attest, or may take new forms, as the EU’s Article 7 Treaty on European Union voting sanctions, or the new EU rule of law budget conditionality rules show. However, justifying such initiatives against populist parties is more normatively complicated, and they are less likely to be used against populist than more clearly anti-democratic or illiberal parties. This means that opposition to populist parties will often be what I call democratic defence as ‘normal politics’ where the nature of the democratic challenge posed by populist parties must first be negotiated in the public sphere; and where both exceptional and normal tools of political opposition may be used, but where the latter typically predominate. The typology I develop aims to better capture this reality.

Inspired by traditional approaches, but departing from them in important ways, my approach classifies IoPPs with reference to two classificatory criteria: the type of political actor that initiates a response against populists; and whether the modes of engagement employed are ‘tolerant’ or ‘intolerant’. This constitutes a typology with six property spaces (see Figure 1). The typology has been tested and adapted in collaboration with a cross-Europe team of researchers studying opposition to populist parties in Poland, Hungary, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Spain and Italy.Footnote 16

Figure 1. Typology of IoPPs

Populist opponents: public authorities, parties and civil society

The first way to classify IoPPs is to distinguish between initiatives undertaken by public authorities, political parties, or civil society actors. Each category potentially incorporates political actors engaged in local, regional, state, and international territorial arenas.

Public authorities encompass individuals or institutions empowered by constitutional or ordinary law, or international agreement, to act in the public interest. Within states this includes the judicial, legislative, and executive branches of government, the bureaucratic apparatus, state agencies and substate authorities (such as regions and local governments). International organisations such as the EU and the Council of Europe can be considered public authorities with authority delegated to make authoritative policy and judicial decisions on behalf of the member states and European citizens. Also included in this category are international agencies carrying out the mandate of their founding governments and initiatives of foreign governments against populist parties (either in opposition or government) in another state.

Political parties are typically organisations which, in Alan Ware’s formulation, ‘seek influence in a state’, often, but not always, fielding candidates in elections to occupy positions in legislative and executive bodies at various territorial levels.Footnote 17 The category includes parties of both government and opposition, and in recognition of parties’ internal diversity, encompasses party leaders, factions, parliamentary groups, and a party’s organisation. It also includes transnational party federations and European Parliament groups.

Civil society actors are private groups or institutions organised by individuals for their own ends. Civil society actors include a very wide range of non-governmental actors, including lobby and advocacy groups, social movements, businesses, churches, trade unions, neighbourhood groups, cultural associations, mainstream and social media. Some civil society actors operate transnationally, such as the Catholic Church, human rights organisations, such as Amnesty International or Human Rights Watch, and social movements like Occupy, Black Lives Matter or #MeToo.

An advantage of adopting this expanded, actor-centred approach is that it acknowledges that public authorities, political parties and civil society actors deploy different sources of authority and resources and play different roles when opposing populist parties. One difficulty with an actor-centred approach, though, is that it draws a line between spheres of political life that are often overlapping. Acknowledging this complexity, relations between public authorities, political parties and civil society actors can be conceived as interconnected spheres (see Figure 2). Where they overlap, we can identify recognisable mixed categories, namely party-controlled public authorities, movement parties and party-linked organisations. Thus, the broader category, public authorities, would typically include Courts, state bureaucracy, government agencies, the ombudsman, parliament, and international organisations, which exercise constitutionally and legally defined public functions (at least in theory) independently of political parties. On the other hand, the offices of president, prime minister, ministers, the cabinet, and those running local and regional governments are typically controlled by political parties.

Figure 2. Overlapping fields: Actors Opposing Populist Parties

Tolerant and intolerant modes of engagement with populists

The second way to classify IoPPs is by ‘modes of engagement’, which can be ‘tolerant’ or ‘intolerant’. In my approach, the difference between these modes of engagement relate to criteria of ‘exceptionality’ and ‘normality’.

Intolerant modes of engagement subject populist parties to ‘exceptional’ treatment. Within liberal democracies, ‘exceptionality’ occurs when populist parties are denied rights, privileges, and respect which political parties would usually enjoy, either by law or in practice, because of their representative function in a democratic society and/or as a governing party in the international sphere. Intolerant modes of engagement include a wide variety of legal and political initiatives, including: restrictions on the right of association (such as party bans); restrictions of expression (such as displaying Nazi paraphernalia); and collusion among mainstream parties to reduce anti-system party success at elections or prevent their participation in government (cordon sanitaire, or ostracism).

In the international sphere, exceptional treatment for populist parties principally entails the denial of rights, privileges, and respect given to those running state institutions by virtue of agreements between states (like treaties) and international norms (like sovereignty and non-intervention). Additionally, in highly developed international organisations like the EU, where populist parties may have important representative functions (like participating in the European Parliament), exceptionality also entails a denial of the rights, privileges, and respect for political parties. Examples of such initiatives include the expulsion or suspension of a state led by populists from an international organisation, and the imposition of political and economic sanctions on such a state, party, or its representatives for actions within the state that are deemed to threaten liberal democratic institutions, principles, and values.

Exceptionality is observed empirically when it can be shown that a rule, practice, or norm with general application is suspended in the case of a populist party. Rules can be formal, such as the legal provisions of a constitution establishing a general right to association and speech, legislation regulating state funding for political parties, or regulations permitting the proportional distribution of positions of power (e.g. in a parliament). Rules may also be informal, including political practices permitting (at least theoretical) collaboration, for example, in elections or government, between political parties with differing ideological positions, and norms of non-violence and civility regulating political engagement in the public sphere.

Tolerant modes of engagement subject populist parties to the same norms, rules and practices in democratic politics and international relations as those applied to other parties and states not led by populists. Tolerant modes of engagement are the negation of intolerant modes of engagement, in that they subject populist parties to ‘normal’, rather than ‘exceptional’ treatment. In other words, tolerant IoPPs engage with populist parties through the modalities of ‘normal politics’: applying ‘ordinary law’, criminal and civil codes in the Courts; application of parliamentary and administrative procedures; information campaigns and civic education; competition among political parties to win ‘office’, ‘policy’ and ‘votes’; and protest, contestation, persuasion, and accommodation in the public sphere. As the negation of exceptionality, ‘normal’ treatment can be observed empirically when opposition to populist parties follows norms, rules and practices with general applicability, even in cases where opponents regard the ideas or behaviour of a populist party as highly objectionable.

Applying these distinctions empirically with colleagues from the Carlsberg Challenges for Europe project, we observed three sets of norms, rules and practices of general application which were suspended or observed, depending on the type of populist opponent. IoPPs undertaken by public authorities, which were in accordance with constitutional norms and rules providing for the free exchange of political ideas within states and the principle of non-interference in the domestic political affairs of states in the international sphere met the criteria of ‘normality’ for tolerant IoPPs. IoPPs suspending or contravening those principles meet the criteria of ‘exceptionality’. IoPPs undertaken by political parties meeting the criteria of ‘normality’ were consistent with the general practices of democratic competition whereby parties keep their options open regarding their political platform and/or alliance strategies. IoPPs meeting the criteria of exceptionality did not. IoPPs undertaken by civil society actors met the criteria of ‘normality’ when they were in accordance with norms, practices and rules favouring non-coercive forms of expressing disagreement with political opponents. I discuss each of these points in more detail below.

It is important to emphasise that the distinction between tolerant and intolerant modes of engagement here is practice-based, rather than a normative theory of what constitutes tolerant or intolerant forms of opposition to populist parties. That is, initiatives are classified depending on whether they are exceptional or not, and more specifically whether they suspend or observe a concrete rule, practice, or norm. Adopting a practiced-based distinction between tolerant and intolerant initiatives has several implications. Firstly, it means that those opposing populist parties may not recognise their actions as tolerant or intolerant in the sense I define it here. For example, it is conceivable that one may adopt what I call a tolerant mode of engagement whilst claiming that the behaviour of the populist party is intolerable. An opponent may take a populist party to court for hate speech or political corruption, challenge its legislative initiatives by voting against them in parliament, or organise a public protest. These actions may be accompanied by denunciations claiming the party is fascist, Nazi, racist, dictatorial, barbaric, or diabolical. On the face of it, these statements do not seem to signal an attitude of tolerance. Nevertheless, the typology classifies initiatives involving the ordinary courts for racist speech, voting in parliament, and non-violent protest as tolerant modes of engagement because these initiatives do not suspend any political right, or deny privileges usually accorded political parties in democratic politics. Once this point is understood, it should become clear that tolerant IoPPs do not require a passive attitude towards populist parties or the acceptance of their ideas and behaviour uncritically. Tolerance entails, as McKinnon defines it, ‘putting up with what you oppose’, even if another person’s life choices or actions shock, enrage, frighten, or disgust.Footnote 18 Tolerance is something other than indifference. It entails putting up with a party you oppose, and when acting politically against it doing so in ways that do not subject it to exceptional treatment.

This tension between daily or public perceptions of what constitutes tolerance and my practice-based conception may raise the objection that I mislabel modes of engagement. It is, after all, reasonable to expect scholarly concepts to resonate with broader public meanings. In response, I would argue that these labels reflect a long tradition in the existing literature distinguishing between tolerant and intolerant forms of opposition to extremist, anti-system, radical and populist parties. Many of the typologies discussed above distinguish between initiatives considered ‘intolerant’, ‘repressive’, ‘exclusive’, or ‘repressive’ on the one hand, and ‘tolerant’, ‘persuasive’, ‘accommodative’ or ‘inclusionary’ on the other.Footnote 19 Similarly, distinctions between ‘exceptional’ and ‘normal’ or ‘ordinary’ responses to parties deemed liberal democratic challengers are a common theme in the literature. For example, many scholars draw a line between militant democracy restrictions on political rights and ‘ordinary law’, which can itself sometimes be mobilised against parties deemed a challenge for liberal democracy (when they commit criminal code violations, for instance).Footnote 20 A similar distinction has been drawn in relation to EU law provisions for sanctions (like Article 7 TEU voting suspension procedures) and procedures used to deal with rule of law violations in ‘normal times’ (like infringement proceedings).Footnote 21 Regarding party responses, the strategy of ostracism has been described as ‘a drastic one, which must be justified by portraying the other as some kind of evil party that should not be dealt with in any way’.Footnote 22 In contrast, the decision to invite a party into a governing coalition has been described as treating them as ‘normal’ parties, or as ‘ordinary political opponents’.Footnote 23

More importantly, I would argue that one reason why labelling modes of engagement tolerant or intolerant is useful, is that it acknowledges a link between scholarly and public debates about tolerance and its limits. Given a presumption in favour of tolerance in liberal democracies, intolerant IoPPs are consistently accompanied by a justification which explicitly or implicitly claims that the ideas and behaviour of their target are illegitimate and/or constitute a threat to liberal democracy. The broad themes of these justifications resonate with more-or-less settled general principles regulating limits of toleration in liberal democracies. Democratic theorists have long debated the conditions under which the tolerant may refuse to tolerate the intolerant. John Locke’s groundbreaking theory of tolerance, for example, did not require the state to tolerate opinions that ‘manifestly undermine the foundations of society’, or religious beliefs deemed to be at the service of a foreign prince (such as, problematically, Catholics).Footnote 24 In our times, intolerant modes of engagement typically acknowledge something along the lines of Popper’s ‘paradox of tolerance’, or the threat that ‘unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance’.Footnote 25 Contemporary justifications for intolerant initiatives also resonate with Rawls’ argument what while ‘members of a well-ordered society should have confidence in the resilience of “free institutions” and the “inherent stability of a just constitution”, tolerance can be reasonably denied “when it is necessary for preserving equal liberty itself”’.Footnote 26

This is not to say that we can turn to regulatory principles or normative convictions to fully explain why opponents adopt one or other mode of engagement with populist parties. We may sometimes be able to do so. However, choices of opposition strategies may be limited by what is practically possible, given the institutional setting and the relative power of, for example, governing populist parties compared to their opponents. Nor can we faithfully expect those who do have the power to deploy intolerant initiatives never to do so maliciously. The point is that using tolerance/intolerance to label different modes of engagement with populist parties, retains the link between practices of opposition and broader philosophical debates about the circumstances under which rights restrictions, or denial of due privileges or respect, can be justifiably limited, at least in a general way. So, while the typology does not provide a theory of tolerant and intolerant forms of opposition against populist parties, it facilitates further reflection in this direction.

Intolerant initiatives opposing populist parties

Intolerant IoPPs subject populist parties to ‘exceptional’ treatment at odds with norms, rules or practices, which grant rights, privileges and respect to parties by virtue of their representative function in a democratic society and in the international sphere by virtue of their governing roles. In addition, intolerant IoPPs are undertaken by those who regard populist parties as illegitimate actors undeserving of toleration and/or claim those populist parties threaten liberal democratic institutions or values.

Rights restrictions by public authorities

When intolerant IoPPs are undertaken by public authorities they seek to delimit the participation of populist parties in the public sphere and/or the impact of their ideas and actions on public policy by: (a) restricting certain kinds of political rights, including rights of association and expression exercised by populist parties and their representatives; as well as (b) restricting rights to obtain access to public goods (such as funds) which they would otherwise have had to right to obtain.

IoPPs that restrict such rights are often typical of militant democracy. Tyulkina helpfully distinguishes between rights restrictions typically justified by the preventive rationale of militant democracy on the one hand, and ‘ordinary’ types of rights-restrictions, on the other.Footnote 27 This distinction is important because civil and political liberties are never absolute and are often subject to limitations quite apart from those justified as preventing harm to the liberal democratic system. Militant democracy, according to Tyulkina, has a narrow area of application, targeting a limited range of rights related to ‘participation in political and public discourse’, rights whose abuse has ‘the potential to affect the operation of the state as a constitutional democracy’.Footnote 28 Thus, limitations on rights like family and private life, and social and economic rights, are difficult to justify with militant democracy rationales because their application is unlikely to affect the operation of the state as a constitutional democracy.Footnote 29 In other words, the criteria of exceptionality is met when those subject to restrictions in their political rights are denied the right to freely exchange their political ideas on the same conditions as others. Another way to think about this is to note that rights-restricting IoPPs suspend tolerance for political speech in relation to two core features of democracy that one of the foremost theorists of democracy Robert Dahl describes as ‘effective participation’ and ‘enlightened understanding’. To satisfy these features, members of a polity ought to have, respectively ‘equal and effective opportunities for making their views known to other members’ and a chance for ‘learning about the relevant alternative policies and their likely consequences’ before new policies are adopted.Footnote 30

Germany, long the prototypical case of a militant democracy, provides many examples of rights-restricting IoPPs. Parties may be banned or denied public funding in Germany if they, ‘by reason of their aims or the behaviour of their adherents, seek to undermine or abolish the free democratic basic order or to endanger the existence of the Federal Republic of Germany’ (Article 21(2-3), Basic Law). Parties that may better fit the definition of an association may be banned for such reasons (Article 9, Basic Law). In addition, rights to freedom of expression, the press, of teaching, assembly, association, privacy of correspondence, posts and telecommunications, rights of property, and of asylum may be denied if used to ‘combat the free democratic basic order’ (Article 18, Basic Law). Other rights limitations include surveillance and reporting of political activity by the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (Verfassungschutz) for parties considered a threat to the free democratic basic order.

In the international sphere, ‘exceptional’ treatment by public authorities entails a denial of ‘rights’ to states led by populist parties. Although the concept of ‘rights’ has a different hue in national compared to international law, we can conceive of rights in the international sphere as entitlements granted by virtue of a state being party to an international agreement such as a treaty, and in case of the EU, by virtue of its laws and regulations. Exceptional treatment in this arena can include denying rights to participate in international institutions (including expulsion, suspicion of voting rights), or the application of sanctions preventing access to public goods (like funds) which a state would otherwise have a right to receive. Application of Article 7(2-3) of the Treaty on the European Union is a prime example of rights-restricting IoPPs in the international sphere. The article permits the Council to suspend voting rights of a member state deemed to be in breach of the common values of the EU.

Ostracism by other political parties

When intolerant IoPPs are undertaken by other political parties, they aim to delimit the participation of populist parties in the public sphere and/or the impact of their ideas and actions on public policy by refusing to cooperate with populist parties, thereby denying them access to positions of political power and signalling their illegitimacy in democratic politics.Footnote 31 Ostracism is the act of intentionally excluding someone from a social group or activity. For political parties, ostracism is a strategy to exclude a populist party from a collaborative political activity on principled grounds, or more specifically because populists are considered illegitimate and/or a threat to liberal democracy. Ostracism meets a criterion of exceptionality because it suspends the general practice in democratic politics whereby political parties keep their options open regarding their policy positions and/or alliance strategies. This practice is not linked to specific norms or rules of democratic politics but contributes to the goal of representation at the heart of modern liberal democracies insofar as it permits parties to respond to changing citizen preferences.Footnote 32 That parties keep their options open does not require they weigh all other parties as equally attractive parties. The literature on coalition formation makes it clear that cooperation choices are influenced by goals of ‘office’, ‘policy’ and ‘vote’ (among other things).Footnote 33

Four subtypes of ostracism can be identified. Electoral ostracism takes place where parties compete to win votes, but decide to exclude, on principled grounds, a populist party from electoral alliances, or from being favoured in other ways, such as being named as a preferred option in two-vote electoral systems. In the parliamentary arena, where legislation, political accountability, and the building and maintaining of government coalitions take place, political exclusion on principled grounds can take different forms. The most widely researched of these is governmental ostracism (or cordon sanitaire), or exclusion of parties from governing coalitions. A third form is parliamentary ostracism, including a principled refusal to support all parliamentary initiatives of a populist party, no matter how minor; a refusal to allocate parliamentary positions (eg committee chairs) to populist parties; or suspension, expulsion or exclusion of parties from parliamentary groups (eg, European Parliament suspensions of the Hungarian Fidesz from European People’s Party in 2019, or the Slovakian SMER-SD from the Party of European Socialists). Public ostracism is the intentional exclusion of populist parties by competitors from activities or events in the public sphere, such as refusal on principled grounds to invite populist parties to public debates.

Coercive confrontation by civil society actors

When intolerant IoPPs are undertaken by civil society actors they seek to delimit the participation of populist parties in the public sphere and/or the impact of their ideas and actions on public policy by using coercion, which in contemporary Europe is usually undertaken to exclude, intimidate or express contempt, rather than to entirely eliminate opponents as a rival. As used here, coercion is a form of advocacy involving what Tilly defines as ‘collective violence’, or a form of contentious claim making which ‘inflicts physical damage on persons and/or objects’.Footnote 34

Coercion is one of the main tactical repertoires available to civil society actors engaged in contentious politics. Tilly identifies seven types of interpersonal violence:Footnote 35 violent rituals, where a relatively well-defined and coordinated group follows a ‘known script entailing the infliction of damage on itself or others’ (e.g. shaming ceremonies, lynching, hunger strikes); coordinated destruction, where persons or groups specialising in violence undertake a program that is damaging to persons and/or objects (e.g. war, collective self-immolation, terrorism, genocide, politicide); opportunism, where ‘as a consequence of shielding from routine surveillance and repression, individuals or clusters of individuals use immediately damaging means to pursue generally forbitten ends’ (e.g. looting, revenge killing); brawls ‘within a previously nonviolent gathering, two or more persons begin attacking each other’s property (e.g. street fights or small scale battles between political rivals); individual aggression, a single actor (or several unconnected actors) engage(s) in immediately and predominantly destructive interactions with another actor (e.g. rape, assaults, vandalism); and scattered attacks where, in the course of small-scale and generally non-violent events, some protestors undertake acts of violence (e.g. assaults on government agents, clandestine attacks on symbolic objects or throwing vegetables or eggs at politicians).

Coercive IoPPs meet a criterion of exceptionality because they suspend the general norm, rules and practices in liberal democracies whereby non-state actors make political claims without coercion. As John Keane observes in Democracy and Violence, a unique characteristic of contemporary democracies is a self-understanding that democracy is a ‘bundle of non-violent power-sharing techniques’ and a ‘learned quality of non-violent openness’.Footnote 36 While democracies never eliminate violence, the ambition to control it is institutionalised in procedures where ‘the violated get a fair public hearing, and fair compensation … [and] those in charge of the means of violence are publicly known, publicly accountable to others – and peacefully removable from office’.Footnote 37 The very concept of ‘civil society’, as Keane observes, has a close affinity with a norm of non-coercion, conceived as ‘a site of complexity, choice and dynamism’ and the ‘elimination of violence from human affairs’.Footnote 38 Those willing to deploy coercion tend to regard their opponents as illegitimate actors undeserving of ‘civility’. They approximate Chantal Mouffe’s conception of ‘antagonistic’ opponents, engaged in a struggle to eliminate an enemy, in a battle over mutually incompatible political projects and identities.Footnote 39

Tolerant initiatives opposing populism

Tolerant IoPPs observe the norms, rules and practices typically granting rights, privileges and respect to political parties by virtue of their representative function in a liberal democratic society, and in the international sphere, by virtue of their governing roles. They may be accompanied by harsh critique and grave disagreement, however.

‘Ordinary’ legal controls and pedagogy by public authorities

When tolerant IoPPs are undertaken by public authorities, they seek to delimit the participation of populist parties in the public sphere and/or the impact of their ideas and actions on public policy by: (a) deploying ordinary legal controls, such as constitutional checks and balances, civil and criminal litigation, legislative and policy change; as well as (b) practices of public pedagogy, such as civic education and condemnatory declarations. These initiatives meet a criterion of normality because they observe the general practice of liberal democratic and international politics whereby political parties, or governments run by them, may freely express their political ideas, or obtain access to public goods, on the same conditions as others. That is, IoPPs in this category use rules and procedures designed to affect all parties and states, address illegal behaviour in general, and/or seek to change political ideas through education, dialogue or discourse. There are four main subtypes.

The first is checks and balances of liberal democratic politics, which are institutionalised in varying (usually constitutionally entrenched) rules for separate but interdependent judicial, executive and parliamentary bodies. It includes the use of procedures vetting executive and judicial appointments; dismissal of governments or ministers in no-confidence votes; impeachment; establishing investigatory committees; the rulings of constitutional courts; and acts of secondary supervisory bodies like ombudsmen or independent media regulators. In the international sphere, rulings of human rights courts, such as the European Court of Human Rights, provide additional checks against rights violations.

A second subtype is judicial control. This IoPP subtype includes invocations of ordinary law against populist parties for infractions mostly spelt out in civil and criminal codes (or equivalent). It includes convictions for corruption and abuse of office, violation of party funding rules, as well as hate speech and hate crimes. While hate speech rules clearly limit freedom of expression, they typically aim to protect the dignity of victims and public peace rather than the subversion of democratic institutions per se.Footnote 40 Holocaust denial sits closer to the boundary between this subtype and rights-restricting IoPPs, given that it has a been ‘closely linked… to efforts on the right to restore the “positive” image of Nazism and prewar fascism’.Footnote 41 Nevertheless, it can also be interpreted as being a ‘particularly malevolent form of racist incitement’, which justifies its inclusion within this category.Footnote 42 In the EU, IoPPs prosecuting illegal acts include tactical use of infringement proceedings against illiberal or anti-democratic practices of member states.

A third subtype is a more diffuse set of policy and legislative responses. These include: (a) new legislation, reforms or public programmes which aim to address problematic behaviour of populist parties (e.g. online hate speech); or (b) longer-term programmes of civic education (eg in the school curriculum, or training of public officials). Programmes run by international organisations for democratic education can also be included in this category. The subtype includes: (c) changes in electoral rules, such as requirements for internal party democracy, or rules affecting populist party vote-to-seat ratios, and forms of what Capoccia calls (d) ‘anti-extremist legislation’, which typically empowers public authorities (especially the executive) with special powers to deal with an immediate extremist threat (among other things) in a state of emergency or siege, or in cases of sedition or treason.Footnote 43 The policy and legislative IoPP subtype also includes (e) policy reforms addressing grievances underpinning populist party support, although care is needed to be sure such reforms are specifically designed to achieve this and not other more general goals.

A final category of tolerant IoPPs by public authorities is public persuasion, which includes speech and acts aiming to dissuade populist parties from undertaking actions that may undermine liberal democratic institutions or to persuade others not to support populist parties or their ideas. It can include speech by representatives of public authorities (presidents, prime ministers, the EU Commission’s president) condemning or demonising populist parties. Demonisation is defined as a moral judgement ‘portraying a person as the personification of evil’.Footnote 44 Public persuasion can also include dialogical processes, whereby populist parties or their supporters are persuaded, through rational argumentation, social learning, moral discourses, emotional appeals or new issue frames, to adopt new opinions, identities and/or interests. This can take place locally, when for example participation of populist parties in governmental or parliamentary institutions may restore populist party members’ ‘faith in politics’,Footnote 45 or in international fora, such as the European Commission’s ‘Rule of Law’ Framework or EU Article 7(1) Treaty on European Union hearings. Public persuasion can also take the form of information aiming to ‘name and shame’ its targets, produced by public authorities such as government departments and agencies, or international bodies such as the Council for Security and Cooperation in Europe and European Commission against Racism and Intolerance.

Forbearance by political parties

When tolerant IoPPs are undertaken by other political parties, they aim to delimit the participation of populist parties in the public sphere and/or the impact of their ideas and actions on public policy by: (a) using ordinary tactics of party-political opposition; and (b) cooperating with, or copying, populist parties in the hope that, in addition to advantages for themselves, IoPPs may induce an ideological moderation of, or weaken, the populist party. Forbearance involves self-restraint, preventing oneself from saying or doing something otherwise preferred, or sufferance, unwillingly granting someone else permission to do something. As Downs has put it in the case of tolerant responses to extremists, there is a ‘tendency to exercise restraint in the face of objectionable pariah parties, even when such tolerance is at odds with other democratic values (protection of minorities, for example)’.Footnote 46 Forbearance in the form of parties’ decisions to cooperate with or copy populist parties they oppose meet a criterion of normality because they observe the general practice in democratic politics whereby political parties keep their options open regarding their policy positions and/or alliance strategies. As noted above, this contributes to the goal of representation at the heart of modern liberal democracies insofar as it permits parties to respond to changing citizen preferences.Footnote 47 As such, a party that exercises forbearance in relation to a populist opponent engages with that party principally to achieve strategic goals of ‘office’, ‘policy’ and ‘votes’.

There are several subtypes.Footnote 48 Policy co-optation involves ‘parroting’ or ‘copying, at least partially [a] party’s core issue positions’ with the paradigmatic example being ‘contagion to the right’ on immigration policy.Footnote 49 Electoral cooperation occurs where a populists’ opponents are willing to form electoral alliances with them. Governmental cooperation involves inclusion of populist parties in governing coalitions, while parliamentary cooperation involves routinised cooperation with a populist party to pass legislation and manage parliamentary business. It could also include less formalised forms of engagement in parliamentary business such as involvement in budget negotiations. A final form is public cooperation, or the routine inclusion of populist parties in activities or events in the public sphere, such as television debates or hustings, and informal dialogue between populist and non-populist parties.

An additional subtype of forbearance is oppositional politics, where populists’ partisan opponents aim to defeat populists using ordinary tactics of electoral campaigning or parliamentary procedure. It includes initiatives of opposition parties to defeat or amend the legislation of a governing populist party, to interpellate government representatives, establish investigatory committees and challenge government acts in the courts. IoPPs such as a motion of no-confidence in the government or a minister, or impeachment, may start out as oppositional politics but if they succeed they become checks and balances, a subcategory of tolerant IoPPs by public authorities. And finally, political persuasion is analogous to public persuasion, involving acts or speech by political parties, their leaders or members aiming to persuade others not to support populist parties or their ideas. It can take the form of condemnation, demonisation, ‘naming or shaming’, or dialogue, among other things. It can also include symbolic actions, such as what Meguid and Albertazzi et al. classify as a strategy of ‘ignoring’ a competing party, which aims to signal to voters that a party’s policy proposals lack merit.Footnote 50

Adversarialism by civil society actors

When tolerant IoPPs are undertaken by civil society actors they seek to delimit the participation of populist parties in the public sphere and/or the impact of their ideas and actions on public policy by using non-coercive means of public protest demonstrating a claim in public.Footnote 51 Adversarial IoPPs meet a criteria of normality by observing norms of civility, at a minimum committing to non-violent engagement with political opponents, but often involving some level of acceptance of political pluralism and the open-ended nature of political struggle.Footnote 52 It is named after Mouffe’s conception of the ‘adversary’ in her model of democratic politics as ‘agnostic pluralism’. As Mouffe argues, the adversary is ‘someone whose ideas we combat but who’s right to defend these ideas we do not put into question’.Footnote 53 Adversarial IoPPs thus tend to treat populists as one opponent among others in political life and use forms of opposition typically deployed against other types of parties as well.

Adversarial IoPPs, as forms of contentious politics, ‘demonstrate a claim, either to objects of the claim, to power holders, or to significant third parties’, but can take a very wide variety of forms.Footnote 54 They include demonstrations, marches, strikes, litigation, lobbying, boycotts, civil disobedience, hunger strikes, art and satire, public debate, (dis)information campaigns, using both traditional and social media. Such actions may involve exclusively local actors or transnational networks. It often involves the formation of alliances between civil society actors and more powerful actors, such as political parties, or pressuring public authorities to use their resources to constrain populist parties. Protest may employ tactical repertoire pursuing instrumental goals, such as publicising a grievance, challenging legislation, or stigmatising an opponent, or take an expressive form, by, for example, modelling through performance some desired alternative forms of social relations, decision-making, or political culture.Footnote 55 Protestors may use non-confrontational insider tactics, such as letter-writing, leafletting, lobbying, press conferences and lawsuits or more confrontational outsider tactics, such as sit-ins, demonstrations, blockades and strikes.Footnote 56 Protest may be conventional ‘ritualised public performances’, using tried and tested action forms accepted as legitimate by elites and easily understood by bystanders.Footnote 57 Or, they may be more innovative, disruptive action forms, perhaps illegal, which ‘break with routine, startle bystanders and leave elites disoriented, at least for a time’.Footnote 58

Conclusion

This article presents a new typology mapping the terrain of contemporary opposition to populist parties. It has, I argue, several advantages. Firstly, the typology eases systematic collection of data on opposition to populist parties. It provides operationalisable definitions and recognisable empirical illustrations of IoPP types and subtypes. This is an advantage over many earlier classification schemes often based on difficult-to-operationalise ideal or constructed types. Cross-national comparison of broader patterns in use of IoPP-types allows us to draw a more accurate picture of how opposition to populist parties varies in different countries, or in relation to the different types of left, right and centrist, governing and opposition populist parties. This allows us to evaluate whether contemporary IoPPs ‘fit’ longer-standing distinctions sometimes drawn between countries seen to adopt either tolerant or intolerant response to challengers, such as contrasts between intolerant, militant tradition in Germany or a more tolerant tradition in the United States, the United Kingdom or Scandinavia. Where the fit is poor, more nuanced models of IoPPs can be developed.

The typology integrates initiatives we know a lot about, such as repressive, state-based initiatives relying on exceptional measures, and responses by political parties, with those which we can observe but which are rarely addressed in the militant democracy and democratic defence literature, such as constitutional review of government acts, criminal proceedings, the actions of other states and international organisations, and protest by civil society actors. Yet it keeps distinctions between tolerant and intolerant modes of engagement with populists, which reflect the broad lines of long-standing debates about how to address the dilemma of ‘tolerating the intolerant’ in liberal democracies. As such, the approach facilitates dialogue between empirical and normative analysis of responses to populist parties, and opens up new terrain for normative theories on lesser-known types of IoPPs (such as ordinary legal controls and pedagogy, coercive confrontation, adversarialism and international IoPPs more generally). Furthermore, by providing a conceptual rubric that better captures the wide range of initiatives actually used in opposition to populist parties, it becomes easier to develop theories of effective opposition. More specifically, the typology points to a wide range of social-scientific fields providing answers to the questions about how law, politics, and international relations produce change. Among other things, it invites reflection on how IoPPs may affect populist parties by enforcing national and international law; manipulating strategic incentives in the context of democratic competition; exploiting interdependence to leverage concessions; and through persuasion.