A number of sound changes raised original /ɔ/ to /u/ in Latin in the course of the third and second centuries BC (in addition to those given on p. 65, this raising also took place before the sequence -lC-, for example *solkos > sulcus ‘furrow’, in the second century). However, the raising was delayed in all cases after /u/, the labial glide /w/ and the labiovelar stop /kw/ until the first century BC.Footnote 1 I have found no certain examples of a spelling <uu> in these sequences prior to the first century. It is often stated or implied in modern scholarship both that original /wɔ/, /kwɔ/ and /uɔ/ became /wu/, /kwu/ and /uu/ at the same time, and that the use of <uo> fell out of use extremely quickly.Footnote 2 However, neither of these statements appears to hold true.

As to the former, the inscriptional evidence, including that after the first century BC and some of the corpora (as we shall see), suggests that /uɔ/ became /uu/ earlier than /wɔ/ and /kwɔ/ became /wu/ and /kwu/.Footnote 3

As can be seen in Table 10, 5 inscriptions, all likely to be from the first half of the first century BC,Footnote 4 show 6 examples of the spelling <uu> for original /uɔ/, alongside 2 inscriptions showing three examples of /uɔ/ being spelt <uo>. Conversely, there are 4 instances of original /wɔ/ and /kwɔ/ being spelt <uo>, and only 1 instance of <uu> which might be dated to between about 100 and 50 BC.Footnote 5 This suggests that /uɔ/ became /uu/ towards the start of the first century BC, whereas /wɔ/ and /kwɔ/ became /wu/ and /kwu/ towards the middle of that century. Of course, the numbers are small, but this does fit in with the later spelling conventions, as will be seen.Footnote 6

Table 10 <uo> and <uu> 100–50 BC

| <uo> = /uu/ | Inscription | Date | Place | <uu> = /uu/ | Inscription | Date | Place |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

suom suom | CIL 12.590 | c. 80 BC (Reference CrawfordCrawford 1996: 302) | Tarentum | duumu(iri) | EDR157325 | 200–71 BC (EDR, palaeography) | Sezze |

| perpetuom | CIL 12.1632 | 80–65 BC (ILLRP 645; Reference ÉtienneÉtienne 1965: 214–15; Engfer 2017 no. 96) | Pompeii | duum.uìr | CIL 12.992 | 100–50 BC (Reference SolinSolin 2003: 97; Reference Gregori and MatteiGregori and Mattei 1999 no. 1) | Antium |

| duum.u[iri] | CIL 12.3091 | 80–50 BC (Reference HarveyHarvey 1975: 49; Reference Granino CecereGranino Cerere 2005 no. 699) | Praeneste | ||||

| duum[uiri ?] | CIL 12.1467 | 80–50 BC (Reference HarveyHarvey 1975: 49) | Praeneste | ||||

| duum.uir, ḍụum.uir | CIL 12.1620, AE 2000.341 | 58 and c. 50 BC (Reference Bispham and CooleyBispham 2000: 52) | Puteoli | ||||

| <uo> = /wu/, /kwu/ | Inscription | Date | Place | <uu> = /wu/ | Inscription | Date | Place |

| soluonto | CIL 12.2951a | 87 BC (Reference RichardsonRichardson 1982: 37) | Contrebia Belaisca | uiuus | AE 1993.545 | Mid-first century BC | Muro Lucano |

| paruom | CIL 4.4972, CIL 12.2540 | c. 78 BC (Reference LiebergLieberg 2005: 62) | Pompeii | ||||

| aequom | CIL 12.588 and p. 913 | 78 BC | Rome | ||||

| seruom | CIL 12.686 | 71 BC | Capua |

In the rest of the first century BC and till the end of the Augustan period, <uo> remains the majority way of spelling both /uu/ and /wu/ and /kwu/. Leaving aside the aqueduct inscriptions from Venafrum, the Fasti Consulares and Triumphales, and the Res Gestae of Augustus, which would distort the figures and will be discussed below, in inscriptions dated between 49 BC–AD 14 I have found the following figures:

5 (16%) instances (from 5 inscriptions) of /wu/ and /kwu/ are spelt <uu>

27 (84%) instances (from 27 inscriptions) of /wu/ and /kwu/ are spelt <uo>

8 (32%) instances (from 8 inscriptions) of /uu/ are spelt <uu>

17 (68%) instances (from 13 inscriptions) of /uu/ are spelt <uo>.

There are very few inscriptions which contain both /wu/ or /kwu/ and /uu/, but just as we will see in the corpora there is none which contains both /wu/ or /kwu/ spelt <uu> and /uu/ spelt <uo>. All three other possibilities are attested: the Laudatio Turiae (CIL 6.41062), from the last decade or so BC, uses <uo> for both /wu/ (uolneribus) and /uu/ (tuom). An inscription on a marble tablet from Herculaneum (CIL 10.1453), shows <uo> for /wu/ (seruom) but <uu> for /uu/ (perpetuum), and it is the same almost consistently in an Augustan edict from Venafrum regarding an aqueduct; across the three copies of the inscription plus a number of cippi marking the route (CIL 10.4842 and 4843; Reference CapiniCapini 1999 no. 1a, 1b, 1c, 2a, b, c, d, f, g, i, l, 17–11 BC), there is 1 instance of riuos and 10 of riuom, alongside 1 instance of [u]acuo[m, 1 of uacuum, and 6 of uacuus. In the Res Gestae of Augustus (Reference ScheidScheid 2007; CIL 3, pp. 769–99), <uu> is used in both contexts: sụụm, annuum, ṃ[agistratu]um, riuum, uiuus.

That there was some confusion about when to use <uo> and when to use <uu> in this period is suggested by the Fasti Consulares (CIL 12 pp. 16–29, FC) and Triumphales (Reference DegrassiDegrassi 1947 no. 1h, FT), erected by Augustus. These in general show a mixture of more old-fashioned and more up-to-date spellings, presumably partly due to their composer working from a range of earlier sources, and partly due to the tendency for names to retain older spellings anyway.

For /wu/ and /uu/ we consequently find an interesting mixture of spellings. In both Fasti we have <uu> used for /uu/ in mortuus (twice, FC) and triduum (FT), and <uu> used to represent /wu/ in the personal names Vulso (4 times, FC, once FT), Ca]luus (FC) and Coruus (3 times, FT), and in the name of the non-Roman people Vulcientib(us) (FT). There is also <uo> for /wu/ in the names of non-Roman peoples: Volsceis (twice, FT), Volsonibus (FT), where the <uo> spelling would remain standard, and the abbreviation uol(nere) (FC). But in addition to these we also find the personal name usually written Scaeuola as Scaeuula (FC), [Sc]aeuula (FT), and the names of the peoples generally known as the Volsinienses as Vulsiniensibus, V]ulsiniensibus (FT). Although these spellings do indeed reflect the expected development of the sequence /wɔ/ to /wu/ before dark /l/ before a back vowel or a consonant, the older spelling Scaeuola appears to have been generally retained, with no other instances of Scaeuula attested, while there are 23 epigraphic instances of the spelling Volsinii and Volsinienses as late as the third century AD. The only other instance with <uu> in this word is Vulsinios (4 times) in a copy of rescript of Constantine (CIL 11.5265, AD 333–337), with many non-standard features.

I would attribute these spellings to an (inconsistent) tendency to modernise the spelling of the sequence of /wu/ to <uu> in the Fasti, even in those lexemes where the old-fashioned spelling would in the end be continued as the standard spelling. Whether this was an idiosyncrasy of the writer of the inscriptions or whether it reflects a more wide-ranging movement towards the use of <uu> for /wu/ amongst whatever body was responsible for the composition of the Fasti cannot be known, although it does fit in with the preference for <uu> also demonstrated by the Res Gestae.

On the basis of this epigraphic evidence, therefore, there is already significant support for the conclusion that /uɔ/ had become /uu/ around the start of the first century BC, while /wɔ/ and /kwɔ/ only became /wu/ and /kwu/ around the mid-point of the century. For both contexts, the spellings with <uo> remained more common to the end of the Augustan period, although /uu/ was more frequently written <uu> than /wu/ and /kwu/ were. In the Augustan period, there are signs of <uu> becoming the standard spelling in official inscriptions for both contexts.

The idea that /uɔ/ became /uu/, and adopted the spelling <uu> earlier, and more thoroughly, than /wɔ/ and /kwɔ/ is supported by the evidence of both the writers on language and of my corpora. Starting with the former, a well-known passage of Quintilian states that <uo> for /wu/ was still used by his teachers towards the middle of the first century AD, who presumably also passed on this spelling at that time, although he subsequently prefers to use <uu>. The examples he gives for the <uo> spelling are of /wu/ (seruos and uolgus). This is not a coincidence: as we have seen, the epigraphic evidence suggests that his teachers might well have already been using <uu> to represent /uu/, and this in fact provides the key to understanding the passages in which he talks about use of <uo>. The two relevant passages are extremely complex:

atque etiam in ipsis uocalibus grammatici est uidere, an aliquas pro consonantibus usus acceperit, quia “iam” sicut “tam” scribitur et “uos” ut “cos”.Footnote 7 at, quae ut uocales iunguntur, aut unam longam faciunt, ut ueteres scripserunt, qui geminatione earum uelut apice utebantur, aut duas, nisi quis putat etiam ex tribus uocalibus syllabam fieri, si non aliquae officio consonantium fungantur. quaeret hoc etiam, quo modo duabus demum uocalibus in se ipsas coeundi natura sit, cum consonantium nulla nisi alteram frangat. atqui littera i sibi insidit (“conicit” enim est ab illo “iacit”) et u, quo modo nunc scribitur “uulgus” et “seruus”.

And even with regard to the vowels themselves it is up to the teacher of grammar to see whether he will accept that in certain contexts i and u are used as consonants, because iam is written just like tam, and uos like cos [i.e. with an initial consonant]. But when vowels are joined together, they either make one long vowel, as in the writings of the ancients, who used this gemination like an apex, or a diphthong,Footnote 8 unless one thinks that a syllable can consist of three vowels in a row, without one of them taking on the function of a consonant. Then, indeed, he will also examine how it can be in the nature of two identical vowels to be combined [in a single syllable], when none of the consonants can do so except when they ‘break’ another [i.e. in muta cum liquida sequence, which can occupy the onset of a syllable].Footnote 9 But nonetheless, the letter i [as a vowel] can occupy the same place as itself [as a consonant] (since conicit is from iacit), as can u, as we now write uulgus and seruus.

And:

nostri praeceptores “seruum” “ceruum”que u et o litteris scripserunt, quia subiecta sibi uocalis in unum sonum coalescere et confundi nequiret; nunc u gemina scribuntur ea ratione, quam reddidi: neutro sane modo uox, quam sentimus, efficitur, nec inutiliter Claudius Aeolicam illam ad hos usus litteram adiecerat.

My teachers wrote seruus (“slave”) and ceruus (“stag”) with the letters u and o, because they did not think that a vowel could coalesce and be combined with itself into a single sound. Now we write double u, for the reason I have given above [i.e. in section 1.4.10–11]: clearly by neither method is the sound which we hear represented, and Claudius’ addition of the Aeolic letter for this usage was not without value.

The exact meaning of these passages is somewhat complicated, and is discussed by Reference ColsonColson (1924) and Reference AxAx (2011) in their commentaries, as well as, for the first passage, Reference ColemanColeman (1963: 1–10). The first passage states that when a vowel is added to another vowel within a syllable this either represents a long vowel (in old writers), or a diphthong (but not a triphthong: three vowels can only go together in the same syllable if one is consonantal <i> or <u>). In addition, <i> and <u> can occupy both vocalic and consonantal positions, as shown by the interchange between /j/ and /i/ in iacit and conicit respectively,Footnote 10 and by /wu/ in uulgus and seruus. If these letters are considered always to be vowels, one then has to explain why they can (nowadays) appear consecutively in the same syllable, when two identical consonants cannot do this (or indeed any two consonants, except in muta cum liquida sequences).

In the second passage, Ax explains unus sonus as the onset and nucleus of a syllable (‘eine neue eigene silbische Toneinheit’). He concludes that, since it was acceptable to use <u> to write /w/ plus a vowel other than /u/, Quintilian’s teachers, not being prepared to countenance <uu> for /wu/, fell back on <uo>, which was acceptable. However, in the absence of other information, this leaves us in the dark as to why <uu> for /wu/ was not to their liking.

Colson takes unus sonus to refer to a diphthong, and says of the second passage:

I think it is clear that the meaning is ‘as they held, two identical vowels could not form a diphthong,’ cf. 4, 11. The reasoning is (a) two vowels in a syllable must form unus sonus, but (b) two identical vowels cannot do this, therefore (c) one of these must be altered.

But if it is true that the rule is that two vowel letters in a syllable must form a (rising) diphthong, the sequence <uo> for /wu/ and /wɔ/ ought to have been just as forbidden as <uu>, since these also did not form a diphthong (and the same would be true of <ua>, <ue>, <ui>).

The missing piece to the puzzle is the fact that, once gemination had ceased to be used to represent vowel length, doubled vowel letters generally could only represent two vowels in two consecutive syllables, as in words like cooperatio and anteeo;Footnote 11 <uu> of course also represents /uu/. These sequences of vowels in separate syllables unquestionably represent two sounds. I take it, therefore, that unus sonus refers to a sequence of sounds within the same syllable, as in <uu> for /wu/. So, Quintilian’s teachers accepted the use of <uu> to represent /uu/, since this was a sequence of two sounds across two syllables, as in all other sequences of two vowels, but not <uu> to represent /wu/, since this would be considered unus sonus.Footnote 12 And in fact, this analysis will be supported when we turn shortly to other writers from shortly before and after Quintilian, who make it explicit that the problem with <uu> is that it ought to represent two vowels in two syllables.

Combining and expanding on Quintilian’s two passages, his argument is as follows: it is necessary to consider whether i and u are to count as vowels or consonants. At least some of the time, i and u should be considered consonants, as in iam and uōs, where they occupy the syllable onset. It is true that when vowel letters are combined in a single syllable they represent either a long vowel (in the olden days) or a (rising) diphthong (e.g. ae, au etc.), but an ostensible combination of three vowels (e.g. seruae) in fact can only be analysed as containing a consonantal i or u. The analysis as vowels is also problematic if we assume that two of them can be combined in a single syllable, when two identical consonants have to be split across a syllable boundary (and indeed two non-identical consonants, except in muta cum liquida sequences); in addition (and more relevantly), as Quintilian’s teachers maintained, two identical vowels have to be split across two syllables too (as in words like cooptō, praeeō, ingenuus). However, now it is recognised that i and u can sometimes function as consonants, allowing the spelling seruus (although consonantal u does somehow sound different from u as a vowel, so it would be sensible to use the digamma for consonantal u).

This analysis is supported when we turn to other writers who talk about the <uo> spelling: Cornutus, Velius Longus and Terentius Scaurus all refer to the old belief that two consecutive identical vowel letters could only represent vowels in separate syllables. This point is made very clearly by Cornutus:

alia sunt quae per duo u scribuntur, quibus numerus quoque syllabarum crescit. similis enim uocalis uocali adiuncta non solum non cohaeret, sed etiam syllabam auget, ut ‘uacuus’, ‘ingenuus’, ‘occiduus’, ‘exiguus’. eadem diuisio uocalium in uerbis quoque est, <ut> ‘metuunt’, ‘statuunt’, ‘tribuunt’, ‘acuunt’. ergo hic quoque c littera non q apponenda est.

There are other words which are written with double u, whose number of syllables increases. Because a vowel attached to another same vowel not only does not form a single syllable, it even increases the number of syllables, as in uacuus, ingenuus, occiduus, exiguus. The same division of vowels also takes place in verbs, as in metuunt, statuunt, tribuunt, and acuunt. Therefore here too one should use the letter c not q [i.e. because in acuunt we have /kuu/, not /kwu/].

We can see that Cornutus, a decade and a half older than Quintilian, does indeed follow the rule that Quintilian ascribes to his teachers that <uu> must reflect two vowels in different syllables. Direct evidence that Cornutus used <uo> for /wu/ may come from the following passage; however, the manuscripts are all corrupt here, so that the reading is not certain, and due to its brevity the passage is also difficult to understand:Footnote 13

‘extinguont’ per u et o: qualem rationem supra redidi de q littera, quam dixi oportere in omni declinatione duas uocales habere, talis hic quoque intelligenda est; ‘extinguo’ est enim et ab hoc ‘extinguont’, licet enuntiari non possit.

Extinguont is written with u and o: this is to be understood here for the same reason which I gave above, when I discussed the letter q. There I said that whenever it appears it ought to be followed by two vowels. Since it is extinguō, from that we get extinguont, even if that cannot be pronounced.Footnote 14

Velius Longus also explains the rule concerning <uu> more clearly than Quintilian:

transeamus nunc ad ‘u’ litteram. a[c] plerisque super<i>orum ‘primitiuus’ et ‘adoptiuus’ et ‘nominatiuus’ per ‘u’ et ‘o’ scripta sunt, scilicet quia sciebant uocales inter se ita confundi non posse, ut unam syllabam [non] faciant, apparetque eos hoc genus nominum aliter scripsisse, aliter enuntiasse. nam cum per ‘o’ scriberent, per ‘u’ tamen enuntiabant.

Now we turn to the letter u. By many of our predecessors primitiuus and adoptiuus and nominatiuus were written with uo, evidently because they held that a vowel could not be combined with itself to form a single syllable, and it appears that they wrote and pronounced this type of word differently. That is, while they wrote o, they said u.

Like Quintilian, Velius Longus, writing probably slightly later, sees the use of <uo> for /wu/ as old-fashioned. In addition to the reference to superiores in the passage above, he subsequently makes the comment

illam scriptionem, qua ‘nominatiuus’ ‘u’ et ‘o’ littera notabatur, relinquemus antiquis.

That spelling, whereby nominatiuus used to be written with uo, we shall leave to the ancients.

Terentius Scaurus mentions the rule more briefly, and again makes it clear that the <uo> spelling for /wu/ is old-fashioned:

proportione ut cum dicimus ‘equum’ et ‘seruum’ et similia debere scribi, quanquam antiqui per ‘uo’ scripserunt, quoniam scierunt uocalem non posse geminari, credebantque et hanc litteram geminatam utroque loco in sua potestate perseuerare, ignorantes eam praepositam uocali consonantis uice fungi et poni pro ea littera quae sit ‘ϝ’.

[The third way of identifying correct spelling] is by analogy, as when we say that equus and seruus and similar words ought to be written like this, although the old writers wrote them with uo. This is because they knew that a vowel ought not to be written twice [in the same syllable], and they believed that the same applied to u, having vocalic force in both places, not being aware that it functioned as a consonant when put before a vowel and that it was used in the same way as the Greeks used ϝ”.

Interestingly, Pseudo-Probus, probably largely repeating Sacerdos’ late third century AD Artes grammaticae, treats <uo> simply as an alternative spelling, with no suggestion that is old-fashioned or unusual:

uos uel uus secundae sunt declinationis, i faciunt genetiuo, hic ceruos uel ceruus huius cerui, neruos uel neruus huius nerui, et siqua talia.

Nouns ending in -uos or -uus belong to the second declension. They make their genitive in -i, as in hic ceruus or ceruos, huius cerui, neruos or neruus, huius nerui, and others of this sort.

Marius Victorinus also does not make an explicit statement about whether the <uo> spelling is old-fashioned, although he does go on, after the following passage, to recommend the use of <uu>, to his pupils, with spelling matching pronunciation:

sed scribam uoces, quas alii numero singulari et plurali indifferenter per u et o scripserunt, ut ‘auos, coruos, nouos’ et cetera.

But I shall write about words which other people have written the same way in the singular and plural, such as auos, coruos, nouos etc.

Donatus does not mention the <uo> spellings, but gives seruus and uulgus as examples of consonantal plus vocalic <u> (Donatus, Ars maior 2, p. 604.5–6 = GL 4.367.18–19).

Looking at the inscriptional evidence after the Augustan period, it seems likely that Quintilian, Velius Longus and Terentius Scaurus’ objections to <uo> may actually be a response to its survival relatively late, even in official and elite inscriptions, throughout the first century AD and into the second. As we have seen, the Res Gestae already uses <uu> for both /uu/ and /wu/ and /kwu/, but <uo> could still be used for both on the gravestone of a high-status woman towards the end of the first century BC, and <uo> for /wu/ in particular is found in a number of inscriptions which could be considered to represent the elite standard.Footnote 15

In legal texts:

aequom (CILA 2.3.927) in a Senatus consultum from Spain, AD 19–20

aequom (CIL 2.5.900) in a Senatus consultum from Spain in several copies from AD 20

clauom (twice, CIL 2.5181; second half of the first century AD) in a lex from Lusitania

uacuom, diuom (CIL 2.1964), diuom (6 times), seruom, suom (CIL 2.1963), diuom (12 times) beside seruum duumuir, duuuiri, suum (CILA 2.4.1201) in several versions of a Lex Flavia municipalis from Spain, with parts dating back to legislation of Augustus

riuom (3 times), alongside riuum, riuus (twice) in the Lex riui hiberiensis from Hispania Citerior, during the reign of Hadrian (Reference Beltrán LlorisBeltrán Lloris 2006)

diuos and –]ụom (CIL 6.40542) on a legal text on a marble tablet, Rome, during the reign of Antoninus Pius.

Other inscriptions of an official or public character:

equom, ]uom beside suum, magistratuum (AE 1949.215) in a tablet recording the honours paid to Germanicus Caesar, from Etruria, AD 20

au]onc[ulus], diuom (CIL 13.1668; Reference MallochMalloch 2020) beside diuus, patruus, arduum. A tablet recording a speech of Claudius, Lugdunum, AD 48 or shortly afterwards

riuom (CIL 6.1246) in an inscription commemorating Titus’ rebuilding of the Aqua Marcia, Rome, AD 79

aequom (AE 1962.288). A bronze tablet recording a rescript of Titus, from Spain, AD 79 or shortly afterwards

diuos (AE 1988.564) in a marble fragment of an imperial Fasti from Etruria, in the reign of Trajan or later

aequom (CIL 3.355). A bronze tablet recording a rescript of Trajan, AD 125–128, from Asia.

In general, <uo> was by no means uncommon. It was perhaps particularly frequent in uiuos for uiuus ‘alive’ on tombstones, where it appears in the formula uiuus fecit ‘(s)he made it while still alive’. A search on the EDCS finds 209 inscriptions dated between AD 1 and 400 which contain uiuos, and 372 containing uiuus. So <uo> represents /wu/ in 36% of these inscriptions.Footnote 16 Of course, some instances of uiuos may be accusative plurals rather than nominative singulars, but given the vast frequency of the uiuus fecit formula, this will make up a very small part of the total. A search with much smaller numbers allows for checking the inscriptions, and confirms this proportion of <uo> to <uu>: there are 55 inscriptions containing (con)seruos in the nominative singular and 118 of (con)seruus = 31% dated between AD 1 and 400.Footnote 17

It also survived for a long time, although its use for /uu/ is rare in later inscriptions. Not including instances of quom for cum (on which see pp. 165–8), I find 68 inscriptions dated between AD 150 and 400 which contain <uo>, of which only 3 have <uo> for /uu/ (CIL 5.4016, AE 1989.388, CIL 3.158); the rest are all /wu/ or /kwu/.Footnote 18 These are found in inscriptions from a range of genres (funerary, honorary, dedication, building, a contract on a wax tablet, a statue base etc.) from all over the empire. To give an extremely rough idea of the frequency of <uo> at this period I searched for <uu> on the EDCS, which found 979 inscriptions containing this sequence from between these dates, giving a frequency of 7%.Footnote 19 A couple of inscriptions from this period suggest that the convention of using <uo> for /wu/ and <uu> for /uu/ may have been maintained: CIL 10.1880 has [P]rimitiuos and [p]erpetuus, CIL 3.5295 (= 3.11709) has uolnus and suum.

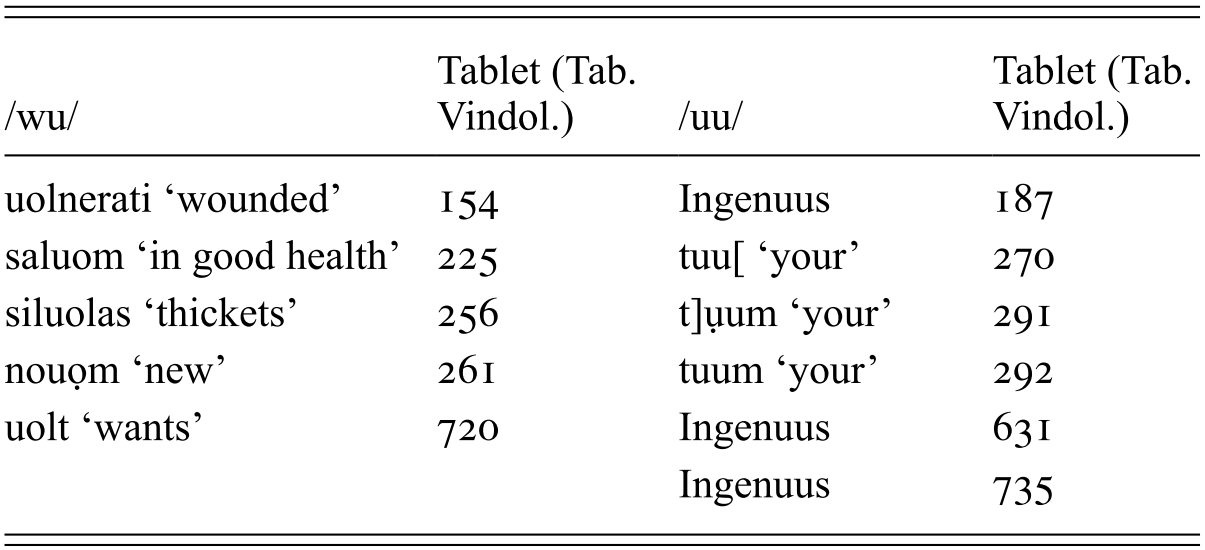

The corpora confirm the tendency among some writers to use <uo> to represent /wu/, and <uu> to represent /uu/ (and never the other way round) and hence the implication that /uɔ/ to /uu/ took place earlier.Footnote 20 This is most clear in the Vindolanda tablets, where the distinction is consistent: /wu/ is always spelt <uo> and /uu/ always spelt <uu> (see Table 11).Footnote 21 Most of the instances of <uo> appear in letters to and from the prefect Cerialis; it correlates with instances of etymological <ss> for /s/ in 225, a draft letter from Cerialis, probably written in his own hand, and in 256, a letter to Cerialis. Most of the latter was written by a scribe, whose spelling is otherwise standard, and it comes from a certain Flavius Genialis of unknown status, but who is probably not the prefect Flavius Genialis. In 261, another letter to Cerialis, presumably from someone of similar rank, it appears in the formula annum nouọm f̣ạuṣṭum felicem ‘a fortunate and happy New Year’. In 720 too little remains to say anything about the contents.

Table 11 <uo> and <uu> spellings at Vindolanda

| /wu/ | Tablet (Tab. Vindol.) | /uu/ | Tablet (Tab. Vindol.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| uolnerati ‘wounded’ | 154 | Ingenuus | 187 |

| saluom ‘in good health’ | 225 | tuu[ ‘your’ | 270 |

| siluolas ‘thickets’ | 256 | t]ụum ‘your’ | 291 |

| nouọm ‘new’ | 261 | tuum ‘your’ | 292 |

| uolt ‘wants’ | 720 | Ingenuus | 631 |

| Ingenuus | 735 |

Although this distribution might imply that use of <uo> is associated with high-status individuals, it also appears in 154, which is an interim strength report, unlikely to have entered the official archives of the unit. Although it does not contain a large amount of text, its spelling is standard except for the contraction of original /iiː/ sequences in is (six times beside eis twice) and Coris ‘at Coria’. Of the tablets using <uu> for /uu/, 187 is an account, whose spelling is, as far as one can tell, standard. 270 is a letter to Cerialis, likewise. 291 and 292 are letters from Severa to Lepidina; the main hands of each are described by the editors as ‘elegant’ and ‘rather elegant’ respectively, and use standard spelling. 631 is a letter to Cerialis from an Ingenuus, who addresses Cerialis as domine ‘my lord’; very little remains, although an apex is used in the greeting formula, which may imply that it was written by a scribe (see pp. 226–32). 735 is fragmentary, but also includes the word dịxsịt. It looks as though use of <uo> is associated with use of etymological <ss> and of <xs>, and both <uo> and <uu> with standard spelling; most of our examples come from texts associated with high-status individuals, but their appearance in a strength report and an account suggest that this is a coincidence, and the absence of <uu> for /wu/ or <uo> for /uu/ suggests that <uo> is the normal way of spelling /wu/ and <uu> /uu/ at Vindolanda.

The same distinction is found in one of the Claudius Tiberianus letters (P. Mich. VIII 467/CEL 141), where <uo> is used for /wu/ in saluom, no]uom, fugitiuom and <uu> is used for /uu/ in tuum (twice). A confused version of the rule also seems to appear in bolt (469/144) for uult ‘wants’ (<o> after /w/ according to the rule, but /w/ spelt with <b>), while <uu> is also used by the same writer in tuum (468/142), but there is no example of /wu/ or /kwu/. All of these letters feature substandard spelling to varying degrees (Reference Halla-aho, Solin, Leiwo and Halla-ahoHalla-aho 2003: 247–50), but they also feature (other) old-fashioned spellings (<k> before /a/ in 467/141; <q> before /u/ inconsistently in 468/142; <q> before /u/ inconsistently, <ei> for /iː/ once in 469/144). Also from a military context, but significantly later, the Bu Njem ostraca show one example of seruu (O. BuNjem 71.5) for seruus or seruum and one example of ṭụụṃ (114.5)

In the tablets of Caecilius Jucundus all 5 instances of /wu/ are spelt with <uo> (see Table 12);Footnote 22 all in the word seruos and by five different writers, one a scribe. All 8 instances except 1 of /uu/ are spelt with <uu>; 2 instances are written by a scribe, and the remaining 6 are by Privatus, slave of the colony of Pompeii, who uses <uo> once in duomuiris, which he otherwise 4 times spells duumuiris.

Table 12 <uo> and <uu> in the Caecilius Jucundus tablets

| <uo> | Tablet | Date | Writer | <uu> | Tablet | Date | Writer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| seruo[s] | CIL 4.3340.6 | AD 54 | Salvius the slave | duumuiris | CIL 4.3340.142 | AD 58 | Privatus, slave of the colonia |

| seruos | CIL 4.3340.20 | AD 56 | Vestalis, slave of Popidia | duumuiris | CIL 4.3340.145 | AD 58 | Privatus, slave of the colonia |

| seruo[s] | CIL 4.3340.138 | AD 53 | Secundus, slave of the colonia | duumuiris | CIL 4.3340.145 | AD 58 | Scribe |

| seruos | CIL 4.3340.142 | AD 58 | Privatus, slave of the colonia | duumuiris | CIL 4.3340.146 | AD 58 | Scribe |

| duomuiris | CIL 4.3340.144 | AD 60 | Privatus, slave of the colonia | duumuiris | CIL 4.3340.147 | AD 59 | Privatus, slave of the colonia |

| seruos | CIL 4.3340.146 | AD 58 | Scribe | duumuiris | CIL 4.3340.150 | AD 58 | Privatus, slave of the colonia |

| merca[t]uus | CIL 4.3340.151 | AD 62 | Privatus, slave of the colonia |

In the tablets of the Sulpicii, /wu/ is commonly spelt <uu>: there are 5 instances (TPSulp. 26, 46, 51, 56, twice) in the word seruus, and 1 in seruum (TPSulp. 51), all written by scribes, between AD 37 and 52. There is 1 example with <uo>, also written by a scribe, at the early end of the date range of the tablets: fụg̣ịṭ[i]ụom (TPSulp. 43, AD 38). There are 4 examples of /uu/ in the lexeme duumuir (TPSulp. 23, scribe; 25, twice, scribe; 110, non-scribe). The tablets from Herculaneum have a single example of [ser]ụụṣ (TH2 A10).

In the curse tablets, there are only two instances of <uo> for /wu/, but Primitiuos (11.1.1/18, second–third century AD, Carthage) is not a certain example, because the writer of the curse also writes Romanous for Rōmānus, suggesting some confusion as to the vowel in the final syllables of these names (and perhaps Greek influence). The remaining form uoltis (1.1.1/1, second century AD, Arretium) also features another old-fashioned spelling, uostrum for uestrum (unless this is analogical on uōs and noster, see p. 106), and shows substandard spelling in interemates for interimātis and interficiates for interficiātis, as well as nimfas for nymphās ‘nymphs’. There are 34 instances of <uu> (from the first century BC to third or fourth century AD, from Rome, Hispania, Britannia and Africa).

There are 6 instances of <uo> for /uu/ beside 18 of <uu> (from the first or second century AD to the fourth century AD; two in Germania, one in Italy and the rest in Britannia), but 4 of the examples of <uo> for /uu/ are dated to the first century BC, when the change was only just taking place (1.4.4/3, 1.7.2/1). The remaining text has 2 examples of suom (1.4.4/1, first–second centuries AD). It also contains old-fashioned <ei> for [ĩː] in eimferis for inferīs. All we can really deduce from the evidence of the curse tablets is that use of <uo> was uncommon in texts of this type, but could be found as late as the second century AD in texts which showed other old-fashioned spellings and, in one case, substandard orthography.

In the corpus of letters, <uo> for /wu/ and <uu> for /uu/ is found in CEL 10 (the letter of Suneros, Augustan period), which contains uolt and deuom beside tuum. This distinction can hardly be considered old-fashioned at this time; the spelling as a whole might be considered conservative, as well as including substandard features (see pp. 10–11). Another letter from the last quarter of the first century BC contains sa]ḷuom (CEL 9). By comparison, CEL 167, a papyrus of c. AD 150 from Egypt, contains dịụus and annuum (as well as ]uum, which could represent /wu/, /kwu/, or /uu/), and CEL 242, an official letter on papyrus from Egypt of AD 505, has octauum and Iduuṃ. In addition, uult (CEL 75) is found in a letter of Rustius Barbarus, tuum (CEL 1.1.18) perhaps third or fourth century AD, suum (CEL 226) in a papyrus from Egypt, AD 341, and ambiguum (CEL 240), a papyrus from Ravenna of AD 445–446. This confirms that at least in the Augustan period there were writers who used <uo> for /wu/, and, in one case, distinguished it from <uu> for /uu/. However, it seems that from the first century AD, <uu> was used also for /wu/.

In the London tablets, there is only a single example of /kwu/, spelt ]equus (WT 41). In the Isola Sacra inscriptions, there is only a single example of /uu/, spelt suum (Isola Sacra 285). There is also only 1 instance form Dura Europos (e]quum, P. Dura 66PP/CEL 191.42, AD 216).