Introduction

Mid-first millennium AD South Asia is notable both for the developments that took place and for the way in which those developments have been studied archaeologically. From the fourth century AD, new kingdoms and states emerged, including, in north and central India, the neighbouring Gupta and Vakataka ‘empires’ (Gupta Reference Gupta1974). Patronage of religious sects associated with the gods Shiva and Vishnu ensured that the institution of the Hindu temple was well established in the cultural landscape (Bakker Reference Bakker2004). Intertwined with these developments was an effervescence of scientific study and artistic expression, exemplified by new Sanskrit literary genres (Kieth Reference Kieth1993) and temple sculptures that define our sense of an ‘Indian’ style (Williams Reference Williams1982). Together, and due to different historiographic factors, these transformations are deemed to mark either a ‘Golden Age’ (e.g. Eraly Reference Eraly2011) or the beginning of an early medieval period in South Asia (Sharma Reference Sharma1965; see also Ali Reference Ali2012). The specificities of these developments are unique to South Asia, but the ways in which they are studied present epistemological (text-archaeology) questions that resonate with approaches to historical periods in other parts of the world.

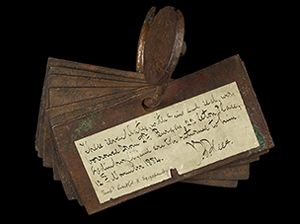

Due to a traditional dominance of socioeconomic histories, scholarship on South Asia has focused on topics of state and society (Sharma Reference Sharma1965; Chattopadhyaya Reference Chattopadhyaya1994). Within this arc of enquiry, historical research has been somewhat functionalist, fixating on the macro level of social structures to explain societal and cultural change (Sharma Reference Sharma1965; Verma Reference Verma1992). Of particular concern have been a series of copperplate charters that record royal grants of land and its agricultural surplus to these new and emerging Hindu temples and associated religious groups—a practice that began with the Guptas during the fourth century AD (Shrimali Reference Shrimali1987; Verma Reference Verma1992) (Figure 1). Not only are these charters the largest corpus of texts for the period, but they are also perceived to have instigated and to reflect a series of societal changes. For many years, donating land and land rights was thought to have brought about a ‘feudal’ society (Sharma Reference Sharma1965) characterised by decentralised power and an agrarian economy. Others have viewed societal developments in terms of socio-political change (e.g. Mukhia Reference Mukhia1981, Reference Mukhia1999; Chattopadhyaya Reference Chattopadhyaya1994). For these scholars, land grants were part of a political strategy that was central to a process of integration, whereby different regions were drawn into new, expanding polities distinct from the earlier ‘ancient’ state (Kulke Reference Kulke1993).

Figure 1. Chammak copperplate of Pravarasena II (scale in cm; British Library Oriental Manuscript shelfmark: Ind. Ch. no. 16; CC BY 4.0 licence).

Debates about the nature of the societal changes that took place have now largely played out, but the idea that these charters were in some way transformative has persisted. Various suppositions can be identified in both the historical and archaeological scholarship, namely that:

(1) the land granted in the charters was uncultivated virgin territory and/or that in granting this land, ‘tribes’ (as they are referred to in both ancient literature and modern scholarship) who existed outside the state were peasantised;

(2) the marshalling of people and resources to cultivate this land led to a significant expansion of the agrarian base for the economy, along with a proliferation of villages; and

(3) the caste system became entrenched in society and religious cults became integrated into the state.

Despite making repeated recourse to these ideas (e.g. Sawant Reference Sawant2008) or drawing attention to how they have been shaped by modern politics (Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2020), archaeologists have studied neither these general developments nor the specific transformations supposedly initiated by the land grants (Kennet Reference Kennet and Bakker2004; Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2019; Kennet et al. Reference Kennet, Hawkes, Willis, Kennet, Rao and Bai2020). Archaeological investigations of the broader medieval period extend only as far as excavating monuments prized for their artistic merits (e.g. Jayaswal Reference Jayaswal2001) and one or two large, archaeologically obtrusive settlements (e.g. Sontakke et al. Reference Sontakke, Ganvir, Vaidya and Joglekar2017; see further Hawkes Reference Hawkes2014). In many respects, this situation is the result of an inequitable relationship between textual and material approaches to the study of historical periods in South Asia that will be familiar to those working on equivalent periods and questions in other regions of the world (Andrén Reference Andrén1998; Moreland Reference Moreland2001), wherein archaeology continues to be excluded from ‘big picture’ conversations about society and culture (Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2003; Ray & Sinopoli Reference Ray and Sinopoli2004). Yet, beyond these epistemological issues, historians of South Asia are even more constrained than colleagues working in many other parts of the world, as they have no place-specific economic sources pre-dating the land grants. It is for both of these reasons—the absence of earlier textual sources and a lack of archaeological investigations—that historical discourse on South Asia has had no choice but to make recourse to wider interpretative frameworks, continuing to focus on big-picture concepts such as social formations or ‘Sanskrit culture’, with little or no understanding of what was happening on the ground. This, in turn, has only widened the gulf between text and archaeology.

Our research has sought to address this situation by investing the study of the land-grant charters—the texts that shape our understanding of the period—with a more materially orientated approach. This not only enables us to assess earlier historical ideas about the changes that occurred, but also to explore how texts and archaeology might usefully relate to each other in the study of the transition between social formations. Here, we are mindful that the land-grant charters were not only texts that can be read, but also objects that were used intentionally and strategically, and that therefore embody practices and social relationships. In the absence of abundant archaeological data for this period, we decided the most effective way to ‘read’ these text-objects archaeologically was to ground them in their landscape settings.

Our preliminary work involved mapping the findspots of all copperplate charters issued between the fourth and seventh centuries AD (Hawkes & Abbas Reference Hawkes and Abbas2016). Investigation of the settings of well-provenienced charters has revealed that they were associated with rich palimpsests of archaeological evidence that both pre- and post-date the charters themselves (Hawkes & Abbas Reference Hawkes and Abbas2016; Hawkes et al. Reference Hawkes, Abbas and Toraskar2020a). Subsequently, we have conducted a series of archaeological surveys to contextualise the social-political instruments of the copperplates in the very landscapes within which they found salience. Our work has focused on one particular region, Vidarbha, which was ruled by the Vakataka dynasty, who moved into this region during the fourth century AD and quickly adopted the new practice of granting land (Kapur Reference Kapur2005). Following archival research (Hawkes & Casile Reference Hawkes and Casile2020), we selected three survey areas centred on charter findspots. Two of these are the sites of Pauni (Deo & Joshi Reference Deo and Joshi1972) and Mandhal (Lal Reference Lal1973: 19; Deshpande Reference Deshpande1974: 24), which were centres of habitation and religious practice both before and during the rule of the Vakatakas. The third zone centred on Chammak, where a copperplate recording a grant of land to the brahmins, or priests, at ‘Charmanka’ was deposited (Figure 1) (Mirashi Reference Mirashi1963: 22–27). Chammak is also located in the western part of the region, enabling us to compare results in different geographical areas (Figure 2). Survey units were defined as 13km radial blocks, designed to identify settlement distribution patterns. The pottery systematically collected from each site was identified with reference to AMS-dated excavated material, and the assemblages were used to date the sites and to characterise the range of local activities that took place.

Figure 2. The Vidarbha region and location of survey frames (figure by the authors).

Details of our methods, analyses and data have been described and made openly accessible elsewhere (Hawkes et al. Reference Hawkes, Abbas and Toraskar2020a; Lefrancq & Hawkes Reference Lefrancq and Hawkes2020) and are therefore not repeated here. Instead, now that we have completed our phasing of the archaeological sites, we present the results and reconstruct the wider societal dynamics of the region before and during the issue of these charters.

Results

Our surveys identified 268 archaeological sites from multiple time periods (Hawkes et al. Reference Hawkes, Abbas and Toraskar2020a). These are categorised as: (1) settlements, indicated by the presence of surface scatters and/or visible habitation mounds, and (2) religious sites, indicated by distinct monumental, structural or carved remains that could be related to particular religious traditions; these include megaliths (an unsatisfactory collective term applied to cist burials, dolmens, monoliths and stone circles) (see Basa et al. Reference Basa, Mohanty and Ota2015); Buddhist caves and stupa monuments (see Hawkes & Shimada Reference Hawkes and Shimada2009); and Hindu sculptures and temples (see Mitra Reference Mitra1971; Michell Reference Michell1977). Most settlement sites were located on cultivated land, though with limited disturbance beyond ox-drawn ploughing and hand-rotavation; relatively good preservation helped to facilitate cross-site comparisons (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Examples of ploughed field surfaces encountered during surveys, with: a) land recently ploughed; and b) after harvest (photographs by the authors).

The extents of surface scatters were recorded as a rough proxy for the size of settlements (Hawkes et al. Reference Hawkes, Abbas and Toraskar2020a, Reference Hawkes, Abbas and Toraskar2020b). Some sites were obscured by modern habitations or located on uncultivated land, which constrained surface visibility. This, together with the fact that surface remains were sampled from the centre of visible scatters, meant that it was not always possible to determine the maximum extent of each phase of occupation at every site. Instead, we used sherd densities and variations within the ceramic assemblages from each site as proxies for relative differences in the intensity and range of activities that took place within those settlements. It is on this basis that our results are visualised and discussed below. While recognising the limitations of such an approach, we note that in almost every instance the highest levels of sherd density and variation correlate to the maximum extent of settlements in as much as they could be ascertained on the ground. The only exceptions are Adam, Mandhal and Pauni, where archaeological remains are obscured by modern habitations (Figure 4). In these cases, it was already known that Adam and Pauni were fortified urban centres measuring at least 50 and 170ha respectively (Deo & Joshi Reference Deo and Joshi1972; Nath Reference Nath2016), while Mandhal exceeded 90ha (Hawkes et al. Reference Hawkes, Abbas and Toraskar2020b).

Figure 4. The site at Pauni: a) the scale of the ancient, fortified settlement and the extent of modern habitation, as viewed from across the Wainganga River; b) how modern buildings obscure the ground surface (photographs by the authors).

Chronologically, the sites date from the early first millennium BC to the mid-second millennium AD. They fall into four chronological brackets, named with reference to the standard nomenclature for the region (Table 1). These are defined based on our dating of the regional ceramics with reference, for the first time in India, to stratified AMS-dated assemblages (Lefrancq & Hawkes Reference Lefrancq and Hawkes2020) and the known dates of religious sites. Significantly—such are the lacunae that exist in South Asian archaeology—our dating of the ceramics in Vidarbha represents the first time that remains from the Early Historic period (a period of almost 1000 years) have been parsed into three distinct phases anywhere in South Asia. Until now, surveys have had to base the dating of sites on the presence or absence of three or four visually distinctive ceramic ‘fossil’ types that rarely account for more than 1 per cent of an entire assemblage. The survey results are discussed below with reference to the phase-wise spatial distribution of sites.

Table 1. Chronological periods referred to in this study.

Early Iron Age (Figure 5)

Pauni survey area

Early Iron Age settlement sites concentrate in the centre of the survey zone, where we also presume considerable activity at the site of Pauni (PNI01) itself. Although concealed beneath a modern-day city, it is clear that Pauni was already a large settlement at this date. There is a small cluster of settlements 3km north of Pauni and a more dispersed distribution of low density/range scatters at a radius of approximately 10km from the site; all of these settlements and scatters are associated with the locations of early megaliths.

Figure 5. Sites dating to the Early Iron Age (c. tenth to fourth century BC) (figure by the authors).

Mandhal survey area

A small cluster of settlements and megaliths centre on the larger sites of Mandhal (MND01) and Wag (WAG01). A high level of activity is also presumed at the fortified settlement at Adam (ADM01). More broadly, settlements are evenly distributed across the survey area and consist of two categories: those with a high density of surface remains spaced approximately 5km apart, and those with lower densities approximately 2km apart.

Chammak survey area

Compared with the Pauni and Mandhal survey areas, there are significantly more early settlements in the Chammak zone; they are also characterised by higher densities of surface remains. Settlements with high density/ranges of material are spaced approximately 5km apart along two of the three main rivers in the area and are interspersed with low density/range sites.

Early Historic (early) (Figure 6)

Pauni survey area

At this date, there was a marked expansion of settlement, with an increase in activity at most earlier settlements, plus eight newly founded settlements. Although settlements continued to cluster around Pauni, new high density/range settlements appeared in the north part of the survey area, approximately 12–14km from the site, interspersed with low density/range settlements. This settlement expansion was accompanied by the foundation of two Buddhist stupas close to Pauni and two Buddhist caves to the north-west.

Figure 6. Sites dating to the earliest phase of the Early Historic period (c. fourth to first century BC) (figure by the authors).

Mandhal survey area

All previous settlements expanded and 13 more were newly founded at this time. These are distributed differently from those around Pauni, with a greater variation between settlements and a visible hierarchy of four tiers of settlements ranked by the density and range of artefacts. Settlement expansion was accompanied by the foundation of seven Buddhist sites: a stupa adjacent to Adam and six cave sites 10–13km distant.

Chammak survey area

Compared with the Pauni and Mandhal areas, there was only a slight expansion of settlement around Chammak, evidenced by a smaller increase in the density and range of surface material at most sites and the establishment of a single new settlement. The overall pattern of settlement distribution remained unchanged.

Early Historic (mid) (Figure 7)

Pauni survey area

During this period, settlement further expanded, with the density and range of material increasing at all but one settlement, and the establishment of three new sites. These developments were accompanied by an extension of the settlement hierarchy in the area, with at least four tiers now visible, within the same overall distribution pattern. There is also a shift in the relative scales and intensity of activities that took place at the sites clustering around Pauni.

Figure 7. Sites dating to the mid-Early Historic period (c. first century BC to third century AD) (figure by the authors).

Mandhal survey area

As at Pauni, there was an expansion of settlement, with all sites growing in terms of the scale and intensity of activity, and the establishment of three new settlements. The overall settlement distribution remained unchanged, although the new settlement at Bhivkund (BVK01) was associated with the Buddhist caves in the vicinity.

Chammak survey area

As before, the Chammak area demonstrates some differences from the other two survey areas. Here, most settlements expanded in terms of the scale and intensity of activity, yet those with previously high densities of surface remains exhibit a reduction in density, while retaining the same overall variation of material. There is a shift in the relative scales and intensity of activities that took place at the sites that cluster together.

Early Historic (late) (Figure 8)

Pauni survey area

This period is characterised by variable trajectories of settlement expansion and contraction. Significant contraction in activity was limited to settlements that previously had high densities/ranges of surface remains. These changes coincided with the granting of a single plot of land recorded on a copperplate buried at Pauni (Kolte Reference Kolte1969: 53–57; Shastri Reference Shastri1997: 97).

Figure 8. Sites dating to the rule of the Vakatakas (c. fourth to sixth century AD) (figure by the authors).

Mandhal survey area

During this period, most settlements either remained the same or expanded—significantly so at Mandhal (MND02) and Wag (WAG02). Some exhibit a slight reduction in the density of surface remains. At Adam, this correlates with excavation data showing a contraction of the settlement at this time (Nath Reference Nath2016). Overall settlement distribution, however, remained the same. This period also witnessed the construction of three temples at Mandhal and grants of seven villages recorded on four copperplates buried near the temples (Shastri Reference Shastri1997: 85–103).

Chammak survey area

The density and range of surface material remained unchanged at most sites, with only four settlements expanding and three contracting. The settlements that expanded were all located along one river, while those contracting were located on another. These changes were contemporaneous with the appearance of a possible temple at Chammak (CMK01), and the issue of a charter recording the grant of Charmanka village to a large group of brahmins (Mirashi Reference Mirashi1963: 23–27).

Discussion

Consideration of the landscape settings of land grants on a regional scale reveals a great deal of information about the areas where land was granted. These insights allow us to contextualise the practice of granting land, and to make inferences about the wider societal dynamics that existed and the transformations that took place over the long term. We see, for example, that each area was settled from a very early period—long before the Vakataka kings began to donate land to brahmins. Further, settlement expanded significantly and variably throughout the region during the later centuries BC. This was most pronounced in the eastern parts of the region, where it was connected with existing (pre-Vakataka) local centres at Adam and Pauni and was contemporaneous with the spread of Buddhism into the area—typical of trajectories of urban development in large parts of India at the time (Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti1995). Yet, differences in urbanism also existed between these neighbouring areas. Settlements around Pauni conform to the ‘classic’ model of early historic urbanism, with a large, fortified city dominating the immediate area (Erdosy Reference Erdosy1988; Allchin Reference Allchin1995); around Mandhal, however, a much smaller fortified centre at Adam was part of a more diffuse distribution of sites, indicating more localised networks of resourcing, production and exchange. By contrast, developments around Chammak continued to follow an earlier, Iron Age pattern of settlement. Such marked variations appear to reflect the existence of different social systems at the local level, each with its own modes of social and economic organisation and possibly even cultural traditions.

Examination of the archaeological landscape also reveals considerable religious dynamism in the region. Textual studies and histories of art have long since charted the existence of local cults and their incorporation into the emerging Hindu sects of Shiva and Vishnu under Vakataka patronage (Shastri Reference Shastri1997; Bakker Reference Bakker2004). Yet, our surveys reveal that these cults and their incorporation into an emerging Hinduism were only one part of a wider and vibrant religious history; this involved not only other pre-existing local beliefs and practices manifest in megalithic monuments and burials, but also a deep-rooted Buddhist monastic presence, both of which appear to have been part of local political economies and continued well into the early centuries AD.

These findings allow us to reflect on the forms of social organisation and transformation that have been associated with these land grants. It is clear that the granting of land did not lead to the settlement of new areas or of tribal populations. Nor were land grants accompanied by an expansion of settlement, which, in turn, makes it unlikely that there was an increase in agricultural production or development of an agrarian economy. Beyond these obvious discrepancies with certain historical theories, grounding the charters in their landscape context improves our understanding of for whom and with what purpose they were intended. As noted above, they record grants of land by Vakataka kings, based in the east of the region, to people referred to as brahmins, or priests. These brahmins are variously portrayed in the historical literature as: an already established part of a uniform ‘Brahmanical society’ that existed across South Asia; as mobile groups who were thrust into new regions alongside grants of land; or as people who became brahmins or began to subscribe to that particular social order—a process formalised through their attribution as such by a dominant sociocultural group (i.e. the Hindu Vakataka kingdom). The fact that there were clearly different social systems across the region suggests that the latter was indeed the case. The land grants may therefore have been contractual agreements, wherein groups occupying similar social roles as brahmins would become part of this new, royal-sanctioned Brahmanical social order in return for land ownership and land rights. As such, these copperplate charters might best be thought of as the embodiment of royal investments in different areas in an attempt to create a new social formation.

The distribution of sites across the region also allows us to reconsider the nature of the state or polity that adopted the practice of issuing land grants. The absence of a uniform settlement pattern in the area around Mandhal, the first capital of the Vakatakas, is significant. It suggests that the Vakataka ‘kingdom’ was, at least initially, more of a material project that was invested in implementing a new social order rather than a regional territory directly ruled by the Vakataka royal family. The archaeological contexts of the land grants also complicate our understanding of the relationship(s) between the Vakataka kingdom and the surrounding polities that received these grants. Whether it is framed in terms of the feudal state or as integrative processes, this relationship is viewed as a power dynamic with the emerging ‘state’, which placed royal-sanctioned Hindu temples at its core, being the dominant party. While this may have been the case, however, appreciating the fact that society as a whole was more ‘pointillistic’ than previously thought forces us to realise one very important point: an exclusive focus on the Vakatakas can never elucidate the ways in which they related to the other political economies around them, nor fully expose the effects of granting land to particular groups within their kingdom (however that kingdom was structured and defined).

Finally, with regard to the societal transformations that accompanied royal land grants, we have already seen that these took place at least 400 years after the most pronounced expansion of settlement across the region and their impact was variable in each local area. In the fourth to sixth century AD, changes in the intensity and variability of activities that took place within and between settlements may have been due to a reorientation of economic or social networks brought about by royal grants of land to temples, or may have been the result of other unidentified factors. Developments are most pronounced in the Mandhal area, where we see a shift in settlement away from the earlier fortified centre at Adam to Mandhal. This is accompanied by the foundation of multiple temples, grants of land to priests seemingly associated with those temples, and a contemporaneous increase in activities at the nearby settlement at Wag. Together, these might reflect a translocation of political and religious institutions to Mandhal and a concomitant movement of economic activities to Wag.

If so, we inevitably arrive at the question of how this archaeological picture of a political project designed to implement a new social order corresponds with that of integrative processes of state formation, as presented by textual historians such as Chattopadhyaya and Kulke. On one hand, we can clearly see that the practice of granting land was integrative in the sense that different parts of the region that fell under the sway of the Vakataka kingdom were integrated into the dynasty's new, planned social order. Equally, it is clear that this new social order was, in certain respects, politically and socioeconomically different to what came before. Yet, on the other hand, this integration does not appear to have been the only causative factor in wider societal developments, if it was indeed causative at all. The multiple different areas and coeval polities evident in the distribution of settlements across the region were already interconnected through various networks of interaction. Further, the only social and economic developments that appear to have stemmed directly from the granting of land were limited to the immediate core area of Vakataka rule—in particular, around Mandhal. It is only here that we see a marked shift in settlement patterns, and economic and, presumably, legal relationships and ritual (for further discussion, see Hawkes Reference Hawkes2021).

Analysis of the ceramics recovered during the surveys (Lefrancq & Hawkes Reference Lefrancq and Hawkes2020) adds nuance to this picture. As might be expected with the use of local clays and different cultural traditions, ceramic types varied between survey zones. Yet, during the later centuries BC, a new class of ceramic was produced in the Chammak area that copied the pottery made around Mandhal and Pauni (Lefrancq & Hawkes Reference Lefrancq and Hawkes2020: 310). This indicates that the early settlement expansion that we see in the region may have been accompanied by a degree of cultural coalescence. The seeds of intra-regional social and cultural rapprochement needed for the Vakataka's successful investment in other areas may thus have been sown long before they came to power. During Vakataka rule, however, ceramic variations between different parts of the region increased, with people in the Mandhal and Pauni zones making several new types of pottery and vessel forms that are not found elsewhere. This suggests that any pan-regional social order created by grants of land existed (at least initially) in a purely political sense. More fundamental societal and cultural changes, ranging from how people organised themselves to the technological innovations and practices evidenced by the archaeological record, remained localised.

Conclusions

Taking an archaeological approach to the study of land-grant inscriptions is clearly of value. This methodological intervention in the study of these text-objects and the changes they are deemed to represent reveals a great deal of new information. Yet, more than this, in grounding texts and historical theories in multi-temporal and multi-scalar archaeological assessments, we have established historical baselines over the longue durée unlike anything previously achieved in the region. Within these frameworks, wider questions of social formation and the transition to the medieval period in South Asia can now be profitably re-posed, perhaps leading to more archaeological questions. The hitherto unrecognised variability within social formations during the early centuries AD is highly significant, and affords great potential for examining at a local scale the ways in which different political economies related to each other and to the Brahmanical polities that have so far been the exclusive foci of text-based historical study.

Beyond the implications for scholarship on South Asia, our material approach to the study of texts also contributes to wider conversations about the relationships between archaeology and history, and between objects and texts. Rather than viewing these as complementary yet distinct fields and data sets that can be interrogated at different scales, we have shown the significant potential in both approaching texts as archaeological objects and in relating archaeology and texts in the study of the transition between social formations. These wider implications extend beyond the methodological level. Studies of medieval urbanism (and indeed the medieval period in general) in Europe are gradually confronting the reality that ‘the medieval’ was not limited to Europe. When considered in this light, it is notable that the patchwork of modes of production and social relations that appears to have characterised the early medieval social formation in Vidarbha chimes well with Wickham's (Reference Wickham2016) ‘leopard spot’ view of the transition to the medieval period in Europe. While we do not for one moment suggest that developments in Europe and South Asia were the same, there is perhaps potential for exploring the dynamics of network urbanism as an important feature of the early medieval period at a global scale.

Acknowledgements

The research presented here was carried out in collaboration between the INHCRF, the IFP and The British Museum. Fieldwork permission was granted by the Archaeological Survey of India (No. F.1I23/1/2014-EE). Subsequent analyses, research and the writing of this and other outputs were carried out at the request of the PI, but without promised payment or furlough, following the end of employment contracts by The British Museum at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, and within the funded term of the project.

Funding statement

The fieldwork formed part of the Asia Beyond Boundaries Project, funded by the ERC (grant 609823), awarded to Michael Willis.