In Canada, as in the United States, food (in)security is defined at the household level. Food security (FS) exists when ‘all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’(1). Food insecurity (FI) happens when at least one of the conditions for FS is not met(1,Reference Tarasuk, Mitchell and Dachner2) . FI is a serious public health concern in Canada, with the latest pan-Canadian data from 2015 to 2016 reporting a 12 % prevalence of household FI(Reference Tarasuk, Mitchell and Dachner3). Yet, certain population groups, such as children, are more susceptible to FI than others – one in six children (15·6 %) is affected by household FI. FI is an important social determinant of health which has been consistently associated with poor physical and mental health outcomes(Reference Tarasuk, Cheng and de Oliveira4–Reference Dubois, Francis and Burnier9). Among children living in Canada, a wealthy country, household FI has been associated with poor diet quality(Reference Kirk, Kuhle and McIsaac8), lower height (including stunting)(Reference Mark, Lambert and O’Loughlin10,Reference Pirkle, Lucas and Dallaire11) , higher BMI(Reference Kirk, Kuhle and McIsaac8,Reference Mark, Lambert and O’Loughlin10) , and socioemotional, cognitive and academic difficulties(Reference Kirk, Kuhle and McIsaac8,Reference Ashiabi and O’Neal12–Reference Godrich, Loewen and Blanchet14) . Household FI appears to influence children’s physical and mental health via both diet and overall family stress or functioning(Reference Ashiabi and O’Neal12,Reference Cook and Frank15–Reference Perez-Escamilla and de Toledo Vianna17) , with some differences found between genders(Reference Dubois, Francis and Burnier9,Reference Mark, Lambert and O’Loughlin10,Reference Jyoti, Frongillo and Jones18,Reference Casey, Simpson and Gossett19) .

Another important health determinant, food skills, an attribute of food literacy, includes the possession of knowledge and skills to select and prepare foods from all food groups using commonly available kitchen equipment(Reference Vidgen and Gallegos20–Reference Slater and Mudryj22). Better food skills support dietary resilience over time and may protect against excess body weight and nutrition-related chronic diseases(Reference Vidgen and Gallegos20,Reference Slater and Mudryj22) . A lack of food skills is, therefore, seen as a barrier to healthy food choices(23,24) . To overcome this barrier and improve food skills among children, school programmes focusing on enhancing food skills have been developed(Reference Bisset, Potvin and Daniel25–Reference Jarpe-Ratner, Folkens and Sharma27). Such programmes have resulted in increased vegetable and fruit consumption, positive lifestyle changes, increased knowledge and improved attitude towards healthy eating among children(Reference Bisset, Potvin and Daniel25–Reference Joshi, Azuma and Feenstra28). Similarly, children’s involvement in family food preparation has been associated with higher preference for, and intake of, vegetables and fruit(Reference Chu, Farmer and Fung29,Reference Chu, Storey and Veugelers30) , self-efficacy for both healthy eating(Reference Chu, Farmer and Fung29) and cooking(Reference Woodruff and Kirby31) and improved diet quality(Reference Chu, Storey and Veugelers30,Reference Leech, McNaughton and Crawford32–Reference Larson, Story and Eisenberg34) .

There is a pervasive perception among community workers, policymakers, governments and the general population that poor food skills contribute to FI(Reference Hamelin, Mercier and Bedard35–Reference Begley, Paynter and Butcher37). This is reflected in the proliferation of community cooking and gardening programmes that have been portrayed as interventions that will enhance FS(Reference Hamelin, Mercier and Bedard35,Reference Begley, Paynter and Butcher37–39) . However, no association of impaired food skills with FI among adults appears to exist(Reference Larson, Laska and Neumark-Sztainer40,Reference Huisken, Orr and Tarasuk41) . For school-aged children, there is a paucity of data and evidence. This is also lacking regarding whether this association is affected by child’s gender. Therefore, the aim of this paper was to examine the relationship between household FI and fifth-grade school children’s involvement in family meal choices and food preparation, used as proxies for children’s food skills(Reference Slater and Mudryj42). The research questions were: (i) Is household FI associated with children’s involvement in family meal choices and food preparation? (ii) Are there gender differences within the association between household FI and children’s involvement in family meal choices and food preparation?

Methods

Sampling and consent

Details on sampling and data collection procedures for the Children’s Lifestyle and School Performance Study (CLASS) have been previously described(Reference Kirk, Kuhle and McIsaac8). Briefly, data from CLASS, a cross-sectional population-based survey conducted among children in the fifth grade (10–11 years old) in Nova Scotia, Canada, were used for this study. All provincial public schools with fifth-grade children (n 286) were invited to participate; 94 % (n 269) agreed to do so. All parent(s)/guardian(s) of participating schools were invited to participate. Parental consent to participate was given for 6591 of the 8736 children (75·4 % consent rate). Of these, 1347 (20·4 %) children were excluded from analyses because they had incomplete data for variables assessed in the current study, leaving 5244 eligible children with complete data (79·6 % participation rate among those who consented).

Measures

Demographic information and household FS status were derived from surveys completed by the parent(s)/guardian(s). Household FS status was assessed using the six-item short form of the US Department of Agriculture Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM)(Reference Bickel, Nord and Price43). This validated instrument was chosen to reduce respondent burden and avoid asking questions about children’s FI because it was deemed too sensitive(Reference Bickel, Nord and Price43). Households were classified as food-secure (score 0) or food-insecure (score 1–6)(Reference Kirk, Kuhle and McIsaac8). FI was treated as exposure in the analyses.

Children’s involvement in family meal choices and food preparation were treated as proxies for children’s food skills. Children were asked by trained research assistants to indicate (i) how often they helped make family meal choices and (ii) how often they helped prepare or cook food at home (e.g. make lunch or snacks). Response options for both questions included ‘never’, ‘about once a month’, ‘about once a week’, ‘2–3 times per week’ or ‘≥4 times per week’.

Data analysis

All analyses, including descriptive analyses, were weighted to represent provincial estimates of fifth-grade child population in Nova Scotia(Reference Veugelers and Fitzgerald44). Mixed-effects multinomial logistic regression models were used to examine the associations of FI with frequencies of children’s involvement in family meal choices and food preparation, which were separately analysed and considered as categorical variables. Models were adjusted for clustering of students in schools, gender, region of residence, number of household residents and parental education attainment. Models were also stratified by gender to investigate gender-specific relationships while adjusting for the same covariates (except gender). Missing values were considered as separate covariate categories, but their estimates are not presented. Normality and homoscedasticity were found to be acceptable for linear regression models. All analyses were conducted using Stata/IC 14.

Results

Demographics

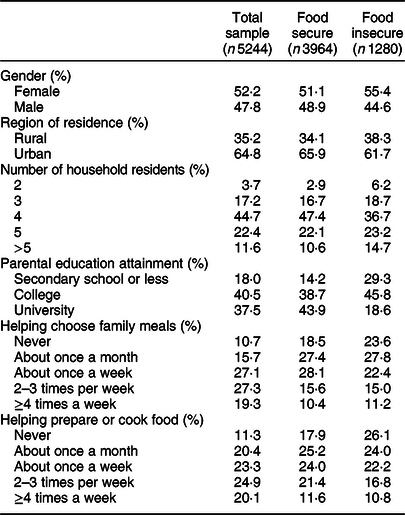

As shown in Table 1, approximately one-quarter of boys and girls lived in food-insecure households (24 %). Most children reported being involved in family meal choices or food preparation at least weekly (74 and 68 %, respectively). Approximately one in ten children reported never helping choose family meals (11 %) or preparing food (11 %).

Table 1 Demographics of fifth-grade children (aged 10–11) in Nova Scotia, Canada by food security (FS) status – Children’s Lifestyle and School Performance Study

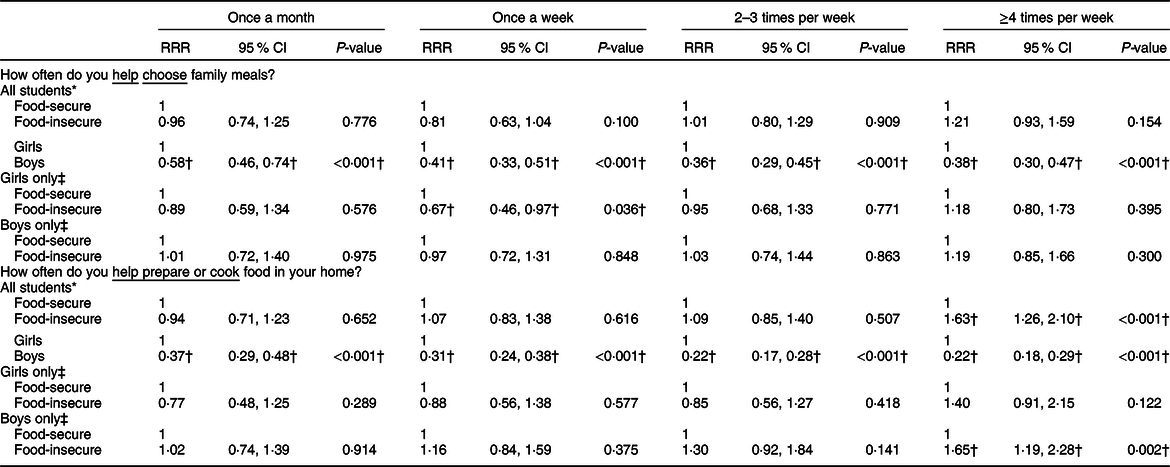

Children’s involvement in family meal choices

Table 2 presents associations between gender, household FI status and frequencies of children’s involvement in family meal choices. Notwithstanding household FS status, boys were less likely to help choose family meals compared to girls (P < 0·001). Children from food-insecure households were as likely to help choose family meals as children from food-secure households. In the gender-stratified model, the likelihood of helping choose family meals once a week was 33 % lower among girls from food-insecure households compared to girls from food-secure households. No differences in boys’ involvement in family meal choices were observed according to household FI status.

Table 2 Associations of food insecurity with the frequency of helping choose family meals and frequency of food preparation/cooking among fifth-grade children (aged 10–11) in Nova Scotia, Canada

Reference: never helping. RRR, relative risk ratio.

* Adjusted for gender, region of residence, number of people in the household and parental education.

† Values are statistically significant (P < 0·05).

‡ Adjusted for region of residence, number of people in the household and parental education.

Children’s involvement in family food preparation

Associations between household FI status and frequencies of children’s involvement in food preparation are presented in Table 2. The expected probability of helping prepare food ≥4 times per week was 63 % higher for children from food-insecure households compared to children from food-secure households. However, the association between FS status and frequency of helping prepare meals was not significant when comparing children’s involvement once a month, once a week or 2–3 times per week. Boys were 63–78 % less likely to help prepare meals compared to girls. In gender-stratified models, significant differences were only observed between boys. Boys from food-insecure households were 65 % more likely than boys from food-secure households to assist with food preparation/cooking ≥4 times per week. No differences in girls’ involvement in food preparation were observed according to household FI status.

Discussion

This paper aimed to examine the relationship between household FI and children’s involvement in family meal choices and food preparation, used as proxies for children’s food skills. Our findings suggest that children living in food-insecure households were similarly involved in family meal choices and were more involved in food preparation than children living in food-secure households. There were gender differences within associations between household FI and children’s involvement in family meals. Girls living in food-insecure households were less involved in food choices than their food-secure counterparts, whereas boys living in food-insecure households were more involved in family food preparation than boys living in food-secure households.

The prevalence of FI among the surveyed children was similar to provincial estimates for Nova Scotia in 2016–2017 (24 v. 22·8 %, respectively)(Reference Tarasuk, Mitchell and Dachner45). Children in the present study were similarly involved in family food preparation to children of similar age in two other Canadian provinces(Reference Chu, Storey and Veugelers30,Reference Woodruff and Kirby31) . Given that research examining the association between FI and food skills among children is lacking, we compared our findings with those among adults. Our findings contrasted with evidence from adults, whereby FI was not associated with food skills(Reference Larson, Laska and Neumark-Sztainer40,Reference Huisken, Orr and Tarasuk41) . Possible explanations could include: that children were helping manage food resources in food-insecure households(Reference Fram, Frongillo and Jones16), that children had to care for themselves while their parents work low-income jobs, or that children ate meals outside of home less often and consequently had more opportunities to be involved in food preparation.

These findings should not be interpreted as a rationale to cease support for interventions aiming to improve food skills among children. Indeed, food skills have been associated with improved diet quality, eating behaviours, dietary variety, higher self-efficacy for healthy eating and healthier food preferences(Reference Slater and Mudryj22,23,Reference Chu, Farmer and Fung29–Reference Larson, Story and Eisenberg34,Reference van der Horst, Ferrage and Rytz46) . Yet, similar to evidence among adults(Reference Huisken, Orr and Tarasuk41), targeting children from food-insecure households for food skills interventions is not supported by current evidence. Findings from the current study suggest that children living in food-insecure households had similar or better food skills than children from food-secure households, as evidenced by their involvement in family meal choices and food preparation. Yet, they may need support to further improve food skills, to ensure they are preparing food safely, and to support increased self-efficacy. Therefore, improving food skills of all children should be explored as a health promotion strategy in the context of population food de-skilling(Reference Slater and Mudryj42). In addition, further qualitative research should investigate how and why FI influences children’s involvement in family meal choices and preparation and explore gender differences.

Strengths and limitations

This study’s results should be interpreted in light of its strengths and limitations. The large population-based sample and use of weights ensured the representativeness of the sample. Food skills were not assessed comprehensively, as only two proxies were evaluated(Reference Vidgen and Gallegos20). The questions used to assess children’s involvement in family meal choices or food preparation in this survey have been used elsewhere(Reference Chu, Farmer and Fung29) and were reported by children themselves. However, more research is required to assess their validity and reliability. Yet, they were positively associated with self-efficacy for healthy eating choices in this sample (data not shown) and another sample using similar questions(Reference Chu, Farmer and Fung29). Information about the type of foods children helped to prepare and the meal preparation tasks children were involved in were not gathered in this study. Therefore, we could not distinguish whether children helped prepare home food from (healthy) unprocessed foods or from (unhealthy) ultra-processed foods(Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Levy47). Future researchers should develop better tools to assess food skills and food literacy among children. Household FI status was also grouped into four categories (FS: score 0; marginal FI: score 1; moderate FI: score 2–4; and severe FI: score 5–6). The results were similar and there was no evidence of a gradient (data not shown). The six-item HFSSM may have underestimated the prevalence of FI as it does not capture anxiety or concerns with regard to accessing food, nor does it inquire about FI among children within the household. Further, it assesses parents’ perceptions, which may not represent children’s lived experience of FI(Reference Fram, Frongillo and Jones16). Lastly, causation could not be inferred due to the cross-sectional study design.

Conclusion

Based on the current study’s findings, interventions aiming to improve food literacy among children to reduce FI are unlikely to be effective because we found that children living in food-insecure households were similarly involved in family meal choices and more involved in family meal preparation, indicators of similar and better food skills, compared with those living in food-secure households. Findings from this study support that household FI is not due to a lack of food skills but most likely due to a problem of access to resources(Reference Tarasuk48). This supports the call of previous research for upstream policies targeting the structural issues underpinning household FI such as low income(Reference Tarasuk, Mitchell and Dachner3,Reference Godrich, Loewen and Blanchet14) .

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to sincerely thank the participants of this study. Financial support: This research was funded by the Collaborative Research and Innovation Opportunities (CRIO) Team programme from Alberta Innovates (grant number 201300671) to Dr P.V. Dr R.B. is funded by a Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship. Dr S.L.G. was funded through an Edith Cowan University School of Medical and Health Sciences Research Collaboration Travel Grant. Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. Authorship: Conceptualisation: R.B., O.K.L., S.L.G., N.W. and P.V.; data curation: O.K.L. and P.V.; formal analysis: O.K.L.; funding acquisition: S.L.G. and P.V.; investigation: P.V.; methodology: R.B., O.K.L., S.L.G., N.W. and P.V.; resources: P.V.; software: O.K.L.; validation: O.K.L.; writing – original draft: R.B., O.K.L. and S.L.G.; writing – review and editing: R.B., O.K.L., S.L.G., N.W. and P.V. Ethics of human subject participation: The Health Sciences and Human Research Ethics Board of Dalhousie University approved the original study, including the informed consent procedure. The Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta approved the present study. The Edith Cowan University Human Research Ethics Committee provided multicentre research project approval.