INTRODUCTION

In Africa, as elsewhere in the world, there is broad agreement that gender equality and women's empowerment are desirable goals, for instance reflected in international agreements and norms, including the Sustainable Development Goals (specifically SDG #5). One concern is that in the absence of interventions that force party leaders to select women, they tend to recruit men (e.g. Butler & Preece Reference Butler and Preece2016). This has amongst other reasons led to an unprecedented interest in studies of gender quotas (Muriaas et al. Reference Muriaas, Tønnessen and Wang2013; Bauer Reference Bauer, Yacob-Haliso and Falola2018; Kang & Tripp Reference Kang and Tripp2018). The main attention of these studies is establishing how and when gender quotas are likely to be adopted (Krook Reference Krook2009; Tripp Reference Tripp2015) and what their effects are on political representation (Franceschet et al. Reference Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012; Clayton & Zetterberg Reference Clayton and Zetterberg2018; Edgell Reference Edgell2018).

We argue that a single focus on quotas as the solution to achieve gender parity is problematic. Formal quotas may not be an option in all states or parties and the overall landscape of initiatives taken to increase women's representation across the world extends beyond quotas (Krook & Norris Reference Krook and Norris2014). Studies have pointed to how certain types of gender quotas are not likely to be effective in majoritarian electoral systems (Larserud & Taphorn Reference Larserud and Taphorn2007), which justifies a careful examination of what type of affirmative action measures work best in African countries with an anglophone institutional legacy. Building on earlier works on electoral funding initiatives in Zambia (Geisler Reference Geisler2006; Sampa Reference Sampa2010) and neighbouring Malawi (Wang & Muriaas Reference Wang and Muriaas2019), we argue that our typologies must acknowledge that other options than electoral quotas are available on the route to achieving parity. Policymakers are not always faced with the choice between gender quotas or nothing but faced with a situation where they must evaluate different options and decide which they find most acceptable. We therefore develop a context-specific typology including the following four affirmative action measures: (1) reserved seats; (2) party quotas; (3) gender-targeted public funding of parties; and (4) candidate-directed funding.

We then explore the determinants of politicians’ preferences between these affirmative action options. Previous studies have found that left-leaning parties are known for more progressive positioning than parties on the right of the economic cleavage (Lovenduski & Norris Reference Lovenduski and Norris2003; Htun & Power Reference Htun and Power2006; Htun & Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2018). African parties, however, are not easily placed on a left-right axis, but tend to frame political issues in valence terms, defined as positioning in accordance with a desired goal with broad agreement (Elischer Reference Elischer2012; Bleck & van de Walle Reference Bleck and van de Walle2013). Testing old and building new theories regarding position formation among politicians is therefore important in the context of democratising countries, because explanatory factors that hold for post-industrial countries in areas of women's rights, such as ideological leanings, cannot easily travel to party systems lacking a manifest economic cleavage. What we aim to identify is the determinants for firm pro-gender equality positioning in this context of non-programmatic politics. Current works in political theory are concerned that the ‘backsliding on gender equality is taking place despite an increasing presence of women in formal politics’ (Celis & Childs Reference Celis and Childs2020: 13). It is thus highly timely to ask who among electoral candidates in the context of non-programmatic politics is ready to ‘speak up’ and support an effective affirmative action measure?

We use a sequential mixed-methods design in a single case, Zambia, to elucidate how different factors affect affirmative action positioning by investigating electoral candidates’ preferences. Zambia possesses characteristics that are disadvantageous to women's political advancement, such as a majoritarian electoral system, no electoral gender quotas and a lack of post-conflict openings for new actors, such as women, to challenge existing power structures (Tripp & Kang Reference Tripp and Kang2008; Stockemer Reference Stockemer2011; Muriaas et al. Reference Muriaas, Tønnessen and Wang2013; Hughes & Tripp Reference Hughes and Tripp2015). In addition, Zambia introduced competitive elections in the early 1990s, and parties are weakly organised, fragmented and not easy to place on a left-right economic axis (Cheeseman & Hinfelaar Reference Cheeseman and Hinfelaar2010; LeBas Reference LeBas2011; Arriola et al. Reference Arriola, Choi, Phillips and Rakner2021). The number of women in parliament remains below the regional average (24.3%) with a range from 9.7% in 1996 to the all-time high of 18% in 2016 (IPU 2019).

To develop our theoretical assumptions on position taking, we conducted a qualitative field study in Zambia in Lusaka in 2015 where we explored which affirmative action measures are relevant in the context and why different actors are likely to support different measures. To further explore whether these positions hold for a larger group, we included both successful and unsuccessful candidates in a larger quantitative candidate study conducted in 2016. It is worth noting that we asked the respondents about their particular position; we asked which solution they would choose, rather than whether they wanted any measure to solve the problem. This approach addresses potential claims of social desirability effects (Streb et al. Reference Streb, Burrell, Frederick and Genovese2008). Respondents do not have to choose between something that they view as morally good or bad, which typically drives such effects (particularly where valence framing is common), but rather between options with varying scales of assumed effect on the recruitment process. We use the most-selected measure as our dependent variable.

As expected, gender was an important determinant, but in a different way than suggested in the literature. Our qualitative interviews with parliamentarians indicated that gender is a weaker predictor of support for the reserved-seats quota than expected. This is because male candidates, in general, are not particularly challenged by such a reform since it often simply works as an add-on to the extant representative system. The survey further unpacked resistance and support for affirmative action alternatives in political recruitment. Overall, reserved seats was the solution most candidates identified as best to solve the problem of gender imbalance in political recruitment; however, this is the most demanding measure and requires the most change out of the options we identified in our typology of affirmative action measures. Quite strikingly, we found that while all candidates prefer quota-centred measures, those who are affiliated with one of the former or current government parties are significantly more likely to support funding measures over gender quotas.

Our study implies that there is a need for more party politics research that theorises what shapes position-taking on different affirmative action measures in the absence of clear ideological cleavages. We argue that some affirmative action measures are more demanding for the government and that those who are aligned with the current or former governing parties are less likely to support such solutions, i.e. the reserved-seats quota in our case. A reserved-seats quota requires legal reform (most often of electoral law) and, depending on the reserved-seat design, involves a costly implementation process.Footnote 1 This article thus brings an important perspective to the literature on political representation in that women, but also men, seem to have their stronger views muted the closer they are positioned to the centre of power. We cannot in our study disentangle whether expressing more conservative views is something that elected representatives learn in office or if this is the type of candidate that the voters preferred. Future research should pay more attention to the variety of affirmative action measures out there, and what knowledge policymakers need about the finer details of what is required to accomplish a goal like gender parity in elected office.

THEORETICAL ASSUMPTIONS ON GENDER-EQUALITY POSITIONING

The literature on gender quota adoption finds that gender has an impact on legislators’ support for gender-equality reform (Lovenduski & Norris Reference Lovenduski and Norris2003; Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud, Esaiasson and Heidar2000; Epstein et al. Reference Epstein, Niemi, Powell, Thomas and Wilcox2005; Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Josefsson, Mattes and Mozaffar2019). In their cross-country survey of how parliamentarians prioritise issues in 17 African countries, Clayton et al. (Reference Clayton, Josefsson, Mattes and Mozaffar2019) find that women representatives articulate a desire to act in the interest of women. Several studies also report that female legislators, whether in Africa or other parts of the world, act on this desire to a greater extent than male legislators (Thomas Reference Thomas1994; Wolbrecht Reference Wolbrecht and Rosenthal2002; Childs Reference Childs2004; Dodson Reference Dodson2006; Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Josefsson and Wang2017). Given this, it is hardly surprising that gender is identified as a key predictor of support for gender quotas to increase women's presence in politics.Footnote 2 Female legislators are more positive towards measures aimed at closing the gender gap in representation, including quotas, and they promote gender equality more than their male counterparts (Lovenduski & Norris Reference Lovenduski and Norris2003; Epstein et al. Reference Epstein, Niemi, Powell, Thomas and Wilcox2005; Keenan & McElroy Reference Keenan and McElroy2017). In a recent study of four European countries, Weeks (Reference Weeks2018) demonstrates that there are also strategic explanations for support of gender quota adoption. She finds that male party leaders may support gender quotas when government parties face competition from the left and when they want to gain more control over candidate selection in the context of high intraparty competition.

Previous research also demonstrates that support for gender-equality issues clusters within gender-progressive partisan coalitions, rather than among women legislators (Htun & Power Reference Htun and Power2006). Hence, the ideological divisions between left and right may override any common interests associated with gender (Lovenduski & Norris Reference Lovenduski and Norris2003). In Africa, many parties are recently established (Debus & Navarrete Reference Debus and Navarrete2020). The expectation is that party identification is largely instrumental and party cues in terms of ideological positing are absent (Lindberg Reference Lindberg2010; Elischer Reference Elischer2012).Footnote 3 However, absence of an ideological cleavage does not mean that party allegiances are irrelevant for policy positioning. As argued by Bleck & van de Walle (Reference Bleck and van de Walle2013), parties in opposition are assumed to be in the position to act differently than those in power. Brader et al. (Reference Brader, Tucker and Duell2013: 1490) highlight that government parties are, on average, more likely to ‘muddy a party's image’ because they are more likely to be, or used to being, confronted by pragmatic details of implementation. In the absence of a manifest economic cleavage and weak policy cohesion, we can develop some assumptions on variation in positioning between candidates representing different parties. Those aligned with the executive are likely to be more in favour of the status quo, while those affiliated with opposition parties are likely to be in favour of radical policy positions that demand legal change. For the gender equality debate, one consequence of these mechanisms is that the closer an elected representative is to power, the more likely it is that this person does not hold a radical position, on gender equality or other policies.

However, there is a probability that radical position-taking is not associated with the success of the party, but rather with the success of individual candidates. Opposition parties might have less to lose and more to gain from ‘flamboyant position appeal’ (Bleck & van de Walle Reference Bleck and van de Walle2013: 1402); this logic could also apply at the individual level. Hence, opposition candidates are in a good position to raise claims of injustices and point to problems that need to be taken care of, without having to suggest any solution and make sure that this solution actually solves the problem. Irrespective of party allegiance, we anticipate that successful electoral candidates are more likely to prefer the status quo than unsuccessful candidates. Furthermore, unsuccessful candidates would be more likely to take a radical position on gender-equality measures than successful ones. Successful candidates, on the other hand, have succeeded in elections under the current system and will most likely favour the extant candidate selection process. For example, Keenan & McElroy reason that Irish candidates ‘who have more political experience might see the quotas as a threat to the status quo and thus be less likely to support them, while those with little or no political experience might be more positive about them’ (Reference Keenan and McElroy2017: 391).

Based on the existing literature, we expect that women, opposition parties, and unsuccessful candidates would favour affirmative action more than men, those affiliated with government parties, and successful candidates. However, this hypothesis is based on empirical evidence from mainly European countries and does not differentiate between different types of affirmative action measures. We argue here that we need to ask about position taking on a range of possible measures in order to (1) reduce social desirability bias in a setting where gender equality is a valence issue and (2) acknowledge that competing affirmative action strategies exist on the ground. As this has not been done before, we need to use our qualitative analysis to refine theoretical expectations to reflect the context.

CASE SELECTION: ZAMBIA

In December 2015, the National Assembly of Zambia turned down an initiative to amend the constitution to change the electoral system from a single member district (SMD) system to a mixed system with proportional representation. The initiative was promoted by actors who wanted an electoral system that better aligned with the idea of descriptive representation – including those from the women's movement (Rule Reference Rule1981; Matland & Studlar Reference Matland and Studlar1996; Tremblay Reference Tremblay2012). This failure to reform the electoral system is illustrative of structural initiatives to increase the number of women in politics in Zambia. Over the past few decades, little progress has been made in terms of using affirmative action measures to enhance women's political representation. Zambia has signaled its commitment to ensuring greater gender balance in politics by ratifying international treaties (CEDAW 2005). Yet, as of February 2019, Zambia had a share of just 18% of female parliamentarians and thus ranked only at 10 out of 15 SADC countries and 115 out of the 193 countries listed in the Inter-Parliamentary Union database (IPU 2019).

Gender quotas were discussed when the Gender Equity and Equality Act (GEEA) was adopted in 2015, but attempts towards further specifications of the law in the direction of establishing a legislative gender quota have been dismissed. In the absence of gender quotas, the political recruitment of women is left in the hands of the selectorates of the main political parties, who have been slow at nominating women (Wang & Muriaas Reference Wang and Muriaas2019). The selection procedures in the main parties are formalised but only vaguely known and there is a constant dialogue between the national leadership and subnational party branches over who should have the final say in the selection process. The former government party, the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD), and the current one, Patriotic Front (PF), use a centralised and exclusive system to select their candidates, with involvement and recommendation rights secured at the local and regional party levels. The main opposition party, United Party for National Development (UPND), uses a centralised and inclusive system, all aspirants compete in advisory primaries in the constituencies. Even if disputed, the party leaders or president have retained a veto right, regardless if this runs counter to or is established in the party constitution. According to Wang & Muriaas (Reference Wang and Muriaas2019), party leaders use this power to uphold a very soft and limited party quota.

In 2011, 108 of 755 candidates were women. In 2016, the number of women remained nearly the same, while the total number of candidates declined to 645. Figure 1 breaks these numbers down to provide a detailed display of variation between the different parties. While there was a rather even display of women candidates across parties in the 2011 elections, the two main parties, the PF and the UPND, overall select more women and get more women elected – partially due to their general electoral success.

Figure 1. Women candidates and success according to party.

Note: Patriotic Front (PF), United Party for National Development (UPND), IND (Independent candidates), Movement of Multi-Party Democracy (MMD), Forum for Democracy and Development (FDD). Total candidates: 755 in 2011, 645 in 2016. Source: Electoral Commission of Zambia. Data compiled by the authors.

A key question is whether party affiliation matters for candidates’ preference formation. It is, however, difficult to place the political parties on a right-left continuum. This placement is typically also of an indication of party-positioning regarding gender equality policies. The Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD) won the founding elections with a landslide. As LeBas argues, from early on the choices of the MMD leaders shaped the fluid and fragmented party landscape that continues today (LeBas Reference LeBas2011). Consequently, even if there is a strong national labour movement, it did not contribute to the manifestation of an economic cleavage, although leading parties may position themselves on economic issues during campaigns (Cheeseman & Hinfelaar Reference Cheeseman and Hinfelaar2010). When a splinter party of the MMD, the Patriotic Front (PF), gained support during the 2000s and finally won the elections in 2011, the party leader, Michael Sata, relied on the combination of a ‘populist message’ and the support of his ethnic-regional community. Still, position-taking on an economic issue does not mean that the parties develop a comprehensive package of positions along the lines that distinguish parties on the left from those on the right in post-industrial countries. The electoral victory of PF in 2011 led to the defeat of the MMD as a political party and most of the MMD MPs changed their allegiances (Bwalya & Maharaj Reference Bwalya and Maharaj2018). Between the 2011 and the 2016 elections the MMD was reduced to a shadow of its former self and the party won only 3 of 156 seats in the National Assembly.

SEQUENCED MIXED METHODS: COMBINING QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE APPROACHES

We employ a sequenced mixed methods approach which allows us to establish a dialogue between the existing theoretical framework and the empirics. As a first step, we conducted a qualitative field study in Lusaka between 27 June and 16 July 2015. This initial work was grounded in the existing literature and involved 41 semi-structured interviews with MPs of both genders from the major political parties, representatives of women's organisations, secretaries of political parties, government officials, international donors and academic consultants. This study explored various aspects of the political recruitment process and the knowledge of affirmative action measures. The findings allowed us to refine existing theory.

As a second step, we used a survey of candidates running in the 2011 national assembly elections in Zambia, conducted from March to June 2016, to study what explains preferences for different affirmative action measures. The candidate survey was organised through the Bergen Berkeley Research Program on Political Parties in the Developing World with funding from the Peder Sather Center for Advanced Study.Footnote 4 The survey targeted two candidates in each of the 150 constituencies per constituency, the winner and the runner-up, and thus aimed to interview 300 candidates of the 755 candidates running for a legislative seat in the 2011 election. The main reasons for targeting both winners and main runners-up were: (1) to not bias the sample to only successful candidates; and (2) Zambian parliamentary elections are predominantly a battle between two candidates, so any further candidates tend to win a very small share of the votes. Due to the pending 2016 elections, it was difficult to include some prominent candidates in the survey, and ultimately we were able to survey 108 candidates. Responses were collected in face-to-face meetings lasting 30–60 minutes. Given the sample of 108 respondents, the targeted sample size of 300, and the population of 755 total candidates, the sample comprised 14.3% of the total candidate population, and the response rate was 36% (108/300 candidates). 57.4% of the respondents were successful candidates, which slightly over-represents successful candidates. The sample reflects the then-existing gender balance, with 83.3% male respondents. The survey included questions on what type of intervention the candidate preferred, whether the candidate was successful, gender, education, age, ethnicity and party affiliation.

GROUNDING THEORETICAL EXPECTATIONS IN QUALITATIVE DATA

We used our interviews to establish the affirmative action measures that were the most context relevant while also drawing on existing works and typologies. A common distinction made in the literature is between reserved seats, party quotas and legislative quotas (Krook Reference Krook2009, Reference Krook2014), but distinctions are also made according to which stage of the selection and nomination process quotas target (aspirant or candidate) (Matland Reference Matland and Dahlerup2006), and whether the quota is mandated by the constitution or by the electoral law.Footnote 5 The type of electoral system in a given context determines which quota design is the most effective, with single-member district electoral systems being a good fit with reserved seats while voluntary party quotas would not be favourable for increasing the number of women in this type of electoral system. Proportional representation systems are more versatile and could be combined with several types of gender quotas (Larserud & Taphorn Reference Larserud and Taphorn2007). As Krook highlights, there will always be tensions regarding which measures to include and which distinctions matter when identifying different types of gender quotas (Krook Reference Krook2014: 1272–3). We found it particularly challenging to settle on potential alternative survey answers that the electoral candidates would understand as clearly distinct. From our interviews it was evident that even if candidates had some knowledge about different affirmative action options, we could not assume that they were familiar with the technical terms used by scholars to distinguish between different types of gender quotas. Hence, our categories needed to be meaningful to respondents who have not necessarily spent much time considering the strength and weaknesses of different gender quota designs. For this reason, we decided to expand the focus from just gender quotas to including the only affirmative action measure used in the context, the funding of women candidates.

Table I presents a two-dimensional typology of affirmative action measures. The first dimension differentiates between measures with or without a gendered electoral funding mechanism. The second dimension distinguishes between public and private measures, in which the public measures require the adoption and implementation of a policy. Combined, these two dimensions comprise the following four categories of political gender-equality measures: (1) reserved seats; (2) party quotas; (3) gender-targeted public funding of parties; and (4) candidate-directed funding.

Table I Typology of affirmative action measures.

We assume that reserved-seat quotas will be the most effective measure in ensuring that a certain number of women are elected. In the quota scholarship there are several studies discussing various aspects of reserved seats, including experiences and effects.Footnote 6 Choosing the reserved-seat option is radical for our respondents, we argue, because it necessitates legal change and depending on the design of the system, a costly and elaborate implementation process. In principle, this should make the reserved-seat option less attractive to those aligning with the current or previous governing parties. This quota type is well-known in the region – of the 34 Sub-Saharan African countries that have quotas for women in politics, 12 have adopted reserved-seat quotas (Burundi, Djibouti, Eritrea, Kenya, Niger, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe). These seats can in many cases be understood as ‘add on’ seats as this measure guarantees the election of a fixed number of women that often are added to the representatives elected from open seats (both men and women). Accordingly, there will often be an increase in the number of parliamentarians when the quota is implemented. This has for instance been the case in countries with single-member plurality systems, such as Kenya, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe. The perhaps most well-known example of reserved seats as an ‘add on’ mechanism is Uganda, one of the earliest reserved-seat adopters in the region (Goetz Reference Goetz2002; Muriaas & Wang Reference Muriaas and Wang2012; Wang Reference Wang2013).

The reserved seats are only open for women, but the electoral rules differ substantially across countries regarding how the competition is organised. Depending on the design, candidates are elected directly by popular vote (e.g. Uganda), indirectly by, for instance, parties (e.g. Tanzania), electoral colleges (e.g. Rwanda), or appointed (e.g. Sudan) (Muriaas & Wang Reference Muriaas and Wang2012; Tønnessen & al-Nagar 2013; Wang & Yoon Reference Wang and Yoon2018). The Kenyan experience, however, demonstrates that implementing a reserved-seat quota is not always straightforward. The 2010 Kenyan constitution entrenches the rule that any one sex should not hold more than two-thirds of the positions in any elective body, but the 47 seats reserved for women elected in 47 women-only counties have so far not been enough to comply with the constitutional provision. There is not a functioning post-election mechanism to ensure that two-thirds requirement is fulfilled at the national level and few women are elected from the 290 single-member open seat constituencies (Berry et al. Reference Berry, Bouka and Kamuru2020). In practical terms the reserved seats could approximate a ceiling rather than a floor, in that women would be discouraged from contesting for the open seats.

Our interviews indicated that candidates unfamiliar with the gender-quota debate would think about reserved seats for women when asked whether they supported gender quotas as an instrument to increase the number of women in elected office. In fact, reserved seats seemed to be the default option for many of our respondents, indicating that this solution was the option that unsuccessful political newcomers were most familiar with. One MP made the following argument for why he supported the adoption of gender quotas in Zambia:

In Kenya, in Uganda, women don't have to go compete with men at the same battle ground. Certain seats are reserved for women. Which I think should be happening here as well. … Our neighbouring countries are doing it, I mean, it is there, why not us? (Habeenzu Reference Habeenzu2015 Int.)

The statement illustrates that reserved seats can work as an addition to the existing representative system and need not come at the cost of their own political careers. This finding indicates that gender is a weaker predictor of quota support than we originally assumed. Hence, we wanted to assess how representative this view of reserved seats was, particularly as the solution requires extensive policy reform.

H1a: Gender does not affect preferences for the most effective measure (reserved seats).

H1b: Opposition members and unsuccessful candidates favour reserved seats more than those affiliated with the current or previous government parties and successful candidates.

Gender-targeted public funding to political parties (Option 3) is also entrenched in law and requires designated funds for its implementation (Muriaas et al. Reference Muriaas, Mazur and Hoard2021). Further, it is a sanction mechanism to assure compliance with what is often referred to as legislative gender quotas in the literature. While list rejection is one kind of sanction mechanism, this type of sanction was referred to as ‘dictatorial’ in one of our interviews (Chilando Reference Chilando2015 Int.) and is clearly problematic in a post-one-party state climate where institutions are frequently manipulated by government parties. According to the Executive Director of the Center for Inter-Party Dialogue, the prioritisation of the GEEA law had led to a discussion about adopting gender-targeted public financing. The idea originated from a provision in the Kenyan Election Campaign Financing Act of 2013 which states that parties will not be eligible for public funding if more than two-thirds of their registered office holders are of the same gender. According to the director, political parties had pushed the idea of a financial reward mechanism because ‘they want institutional support, they want public financing’ (Chilando Reference Chilando2015 Int.).

Given that the concept of legislative gender quotas is very broad, we chose to focus on gender-targeted public funding as the mechanism had been discussed among key actors. The costs of non-compliance are often low for party leaders as the financial loss is likely to be outweighed by increased chances of winning a seat in the National Assembly (Fréchette et al. Reference Fréchette, Maniquet and Morelli2008; Ohman Reference Ohman2018; Feo & Piccio Reference Feo and Piccio2020; Muriaas et al. Reference Muriaas, Wang and Murray2020). We thus assume that this is a solution that will be supported among those affiliated with the former of current government parties, because of the level of knowledge about this measure and the financial gain promised to parties. In Sub-Saharan Africa, six countries have legislation for gender-targeted public funding to political parties (Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Kenya, Niger, Ethiopia and Mali),Footnote 7 half of which have such a mechanism attached to a legislative candidate quota.Footnote 8

H2: Candidates affiliated to the former and current government party favour party-directed funding more than those affiliated with parties that have never formed government.

The two other options do not necessitate any legal changes, and implementation does not rely on the government's capacity and/or will. Voluntary party quotas (Option 2) are found in seven countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (Botswana, Côte d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Mali, Mozambique, Namibia and South Africa), and are found to be effective in countries both with proportional representation electoral systems and where the dominant party wholeheartedly commits to advancing gender balance in politics. Voluntary party quotas are seen as less successful in majoritarian electoral systems (Larserud & Taphorn Reference Larserud and Taphorn2007). Party quota rules are often disregarded by party leaders if application is perceived to weaken the party's chances of winning a constituency seat because of the dynamics that play out in competitive SMD electoral systems. In our interviews, candidates often stressed the need for the party selectorate to pick the candidate with best merits and resources and suggested that men were more likely to have the requirements needed to win support. Voluntary party quotas are likely to be ineffective in Zambia due to weakly institutionalised party organisations and an SMD electoral system.

Candidate selection procedures in all parties are to some extent centralised as the party leader makes the decision regarding the final nomination (Wang & Muriaas Reference Wang and Muriaas2019). The procedures are, however, localised because the process of identifying candidates and formulating recommendations starts with selection meetings at the local branch level in all the main parties. The outcome of the process is often not known until the party leader submits the list to the electoral commission (Wang & Muriaas Reference Wang and Muriaas2019). Our interviews indicated that women candidates had a weak linkage to political parties. The potential pool of credible women candidates rarely comes from the women's wings of parties, which often consists of ordinary grassroots party members who hold the function as party mobilisers. As one female MP explains: ‘You have to have resources to run. Members of the women's leagues don't have that money’ (Kalima Reference Kalima2015 Int.), illustrating how outsiders with resources and money were preferred in the selection process over insiders with a proven record of accomplishments from the women's league. We included party quotas as an option since it is relevant, and we assume that women who tend to be marginalised from the inner circles of power in the parties will not favour an option controlled by political party elites.

H3: Men and successful candidates favour voluntary party quotas more than female and unsuccessful candidates.

Candidate-directed funding (Option 4) represents the status quo in Zambia, and is used in neighbouring Malawi, as well as in other well-known Western countries with majoritarian elections, such as Canada, the UK, the USA and Australia (Muriaas et al. Reference Muriaas, Wang and Murray2020). As access to money is crucial to the campaign process, funding earmarked for women has the potential to ensure important support for female candidates and places no burden on party leaders or the government in most countries. The Zambian women's movement was the first in Africa to pilot a non-partisan electoral funding initiative that targeted all women candidates ahead of the 1991 election (Geisler Reference Geisler2006). The initiative was particularly prominent in the 2001 and 2006 elections when the women's movement, with support from international donors, provided 70 bicycles, posters, and chitenge materials to women who ran for parliament (Sampa Reference Sampa2010).Footnote 9 The initiative was also followed up in the 2011 elections.

However, the initiative has remained controversial since its introduction. The strategy has been criticised for siding with the opposition, and meetings have been boycotted, disrupted and sabotaged (Geisler Reference Geisler1995). Yet women MPs tended, with some exceptions, to support gender-targeted candidate funding, but highlighted that the amount received is far from sufficient to cover the exceedingly high costs involved in winning both the nomination and the parliamentary election. One woman MP lamented the contribution she received like this: ‘I got 1000 kwacha from the women's lobby to help me with my campaign. It was nothing! But thanks anyways’ (Mazoka Reference Mazoka2015 Int.). However, women may prefer the status quo to the other two options if they fear that none of the other affirmative action measures will benefit them.

H4: Women favour the status quo (candidate-directed funding) more than men.

CANDIDATE SURVEY: DATA AND FREQUENCIES

In the survey of parliamentary candidates, we included the following question about what type of measure a candidate would see as the best option when aiming for gender balance: ‘Zambia has signed the SADC Protocol on Gender and Development, which requires policies to increase the number of women in parliament to 50 percent of all seats. In your opinion, what is the best way to achieve this goal in Zambia?’ In line with the findings from the qualitative analysis and literature, the candidates could choose between the following answers: (1) Seats are reserved for women in parliament; (2) Parties adopt voluntary quotas for parliamentary nominations; (3) Women receive public funding for their election campaigns; (4) Parties adopting an equal number of men and women for parliament should receive extra public funding; (5) No such measures should be adopted; (6) Don't know (this option was not read aloud).

As a first step, we explore the more general univariate statistics regarding the reported preferences to see broadly who chose what type of measure. For the second step in the analysis, we contrast the preferences for reserved seats with a preference for any other option (H1a and H1b). This dependent variable is dichotomous, so that 1 indicates a preference for reserved seats specifically, and 0 indicates any alternative to this option. To test H2, H3 and H4 we adopt a similar strategy, but then contrast preferences for party-directed funding, voluntary party quotas, or candidate-directed funding with any other option.

We analyse dependent variables mainly through two-samples t-tests in order to identify what candidate characteristic is associated with what type of measure. This allows us to see whether the mean choice between two options is statistically different for two groups, e.g. men and women. While we focus on the indicators that we expect to impact this choice, we also examined other candidate characteristics in relation to the most popular measure, i.e. reserved seats. These tests, as well as the full results of the analyses, are included in Table AI and AII of the Appendix. Furthermore, we analysed the alternative vs. reserved-seats variable using a multivariate logistic regression model that includes the relevant independent variables as well as two additional controls. This analysis functions as a robustness check and is included in Table AI of the Appendix. The Appendix also offers the exact wording of the indicators used.

Results

First, we are interested in determining which candidate prefers which type of measure, i.e. men versus women, successful versus unsuccessful candidates, and belonging to the current or former governing parties. Identifying how many candidates select the various options will provide an initial overview of the choices that candidates tend to make.

Table II shows that the majority of candidates favoured the reserved-seats measure (58%), and that the candidate-directed funding measure – the most similar to the status quo – was least favoured (9%). This implies, on the one hand, that an overwhelming majority of respondents preferred an alternative to candidate-directed funding (91%), and that, on the other hand, an absolute majority of the respondents preferred the most radical gender-equality measure.

Table II Prioritised measures for gender equality by gender, success and ruling party.

Note: Six respondents opted for ‘No such measure’, and 2 for ‘Don't know’.

Table II shows some preliminary support for our expectations. Ten out of 18 women prefer reserved seats, suggesting that women tend to regard this type of quota as most helpful in ensuring more seats for women in parliament. One explanation for this may be that there are currently so few women in parliament that a potential glass ceiling does not seem such a threat. In addition, none of the women chose the voluntary party quota, while almost 20% of men did (providing support for H3). The lack of popularity for this option among women may be related to scepticism about party quota effectiveness, since candidate selection within parties is dominated by strong, predominantly male networks that are not easily broken (Wang & Muriaas Reference Wang and Muriaas2019). Successful (male) candidates are more supportive of voluntary party quotas than unsuccessful candidates (H3).

Similarly, a majority of men prefer reserved seats (48 out of 82 men). This preference indicates that men do not view reserved seats as threatening their own careers, as it offers women distinct paths to parliament. Table II suggests that men and women are roughly equally positive (supporting H1a) about reserved seats. This pattern remains also when looking at success and belonging to a ruling party (the previous or current): e.g. successful men (46.7%) and women (50.0%) select the reserved seats option less than unsuccessful men (73.0%) and women (66.7%). The most unpopular measure among men is candidate-directed funding. Such a measure may appear as particularly unfair due to the potential exclusion of men with fewer resources. Table II suggests, as expected by H4, that women are somewhat more positive about this option than men – though only those that are associated with a ruling party.

Further, Table II shows that candidates who were unsuccessful or not affiliated with a party that has been in government tend to favour reserved seats more than those who were successful or affiliated with a governing party (supporting H1b). This pattern is similar among men and women. Party-directed funding is somewhat more popular among members of a former or current governing party (H2), though not overwhelmingly so, and appears mostly driven by men belonging to a ruling party.

Second, we look more closely at who prefers which option. Figure 2 shows the results of the relevant t-tests examining what affects a preference for reserved seats versus any other measure. On the one hand, the results suggest that the difference in preferring reserved seats between men (59%) and women (56%) is not statistically significant. Indeed, the top left panel in Figure 2 shows, in line with our expectation (H1a), that both groups are approximately equal in their preference for this measure.

Figure 2. Preferences for reserved seats (vs. all other options).

Note: The panels reflect results from bivariate t-tests and gives the mean of each ‘group’ on the dependent variable as well as the 90% confidence interval. The dependent variable indicates a preference for reserved seats (1) versus a preference for any other measure (0). The grey circles in each panel indicate actual observations. The precise means and difference in means, as well as information about the level of statistical significance, are reported above each panel. * P <0.1; ** P <0.05; *** P <0.01.

On the other hand, and in accordance with H1b, the results reveal that candidates who were successful in the elections select reserved seats less as their preferred option, than those who were unsuccessful. The top right panel in Figure 2 shows that the difference in selecting this option (72% vs. 47%) is statistically significant at the 95% level. It needs to be noted here, however, that there is a chance that experience rather than success drives the results. Since our survey was conducted 5 years after the election, successful candidates also gained 5 years of experience. Moreover, it is possible that candidates were partly elected on their position on this issue in the first place. Our data do not allow us to test whether it is being-elected, success, or experience that affects candidates’ choice. However, considering the results pertaining to the ruling party (see below), which does not systematically co-vary with success in our sample, our expectation may still be supported: Jointly, the results suggest there is something about being closer to power that helps determine what one sees as the best solution.

Moreover, the bottom right panel in Figure 2 shows that candidates affiliated with one of the main ruling parties (PF or MMD) exhibit a similar pattern, even when controlling for success (see Table AI in the Appendix). In accordance with our expectation, they are less likely than opposition candidates to select reserved seats. The bottom two panels illustrate the importance to distinguish between the current governing party and combining candidates of the two main ruling parties: candidates from these parties are more alike, and different from candidates of the more systematic opposition parties. Therefore, being a member of the current governing party is not a predictor in itself for selecting an alternative to reserved seats (bottom left panel) – though being a member of the current or the former governing parties is. Overall, the results in Table II provide support for H1b, in that candidates who are part of the opposition and are unsuccessful tend to support reserved seats more.

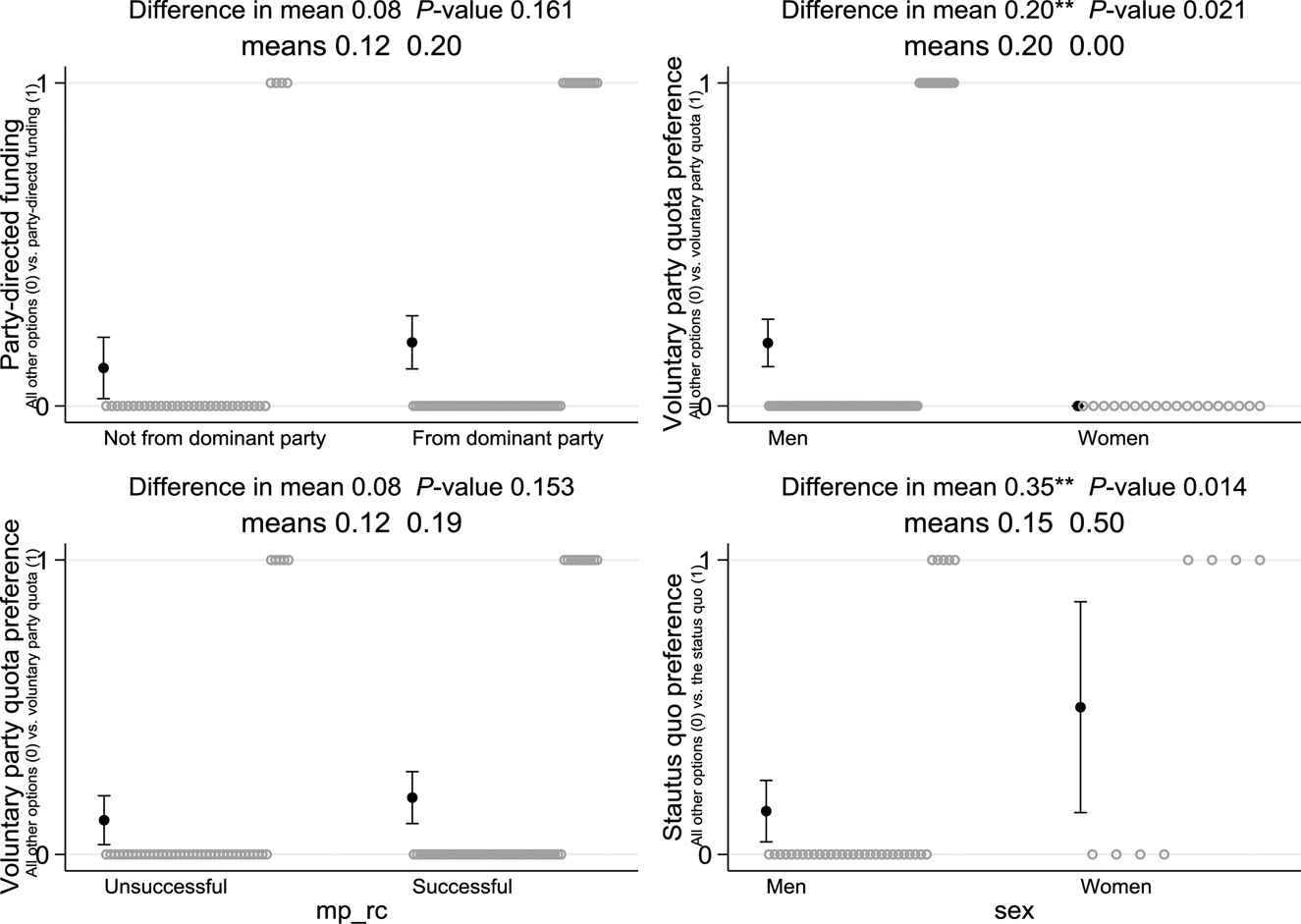

Further, Figure 3 shows the results relating to hypotheses 2, 3 and 4. The top left panel shows that the difference between being affiliated to a current (PF) or former governing party (MMD) or not results in only a small and not significant difference in preference for the party-directed funding option. This result challenges our expectation in H2. The top right and bottom left panels deal with preferences for voluntary party quotas. The panels show that men favour this measure significantly more than women, as expected in H3, but that success does not seem to matter. The results thus provide mixed support for our expectation in H3. Lastly, the bottom right panel shows that women tend to favour the status quo more than men, and this difference is statistically significant at the 95% confidence level. This finding supports H4.

Figure 3. Preferences for directed funding, voluntary party quotas and candidate-directed funding (vs. all other options).

Note: The panels reflect results from bivariate t-tests and gives the mean of each ‘group’ on the dependent variable as well as the 90% confidence interval. The dependent variable indicates a preference for party directed funding (upper left)//voluntary party quotas (upper right and lower left)//candidate-directed funding (lower right) (1), versus a preference for any other measure (0). The grey circles in each panel indicate actual observations. The precise means and difference in means, as well as information about the level of statistical significance, are reported above each panel. * P <0.1; ** P <0.05; *** P <0.01.

CONCLUSION

We have studied the relationship between candidate characteristics and affirmative action position-taking in an African context of low party policy cohesion. Our qualitative study was used to identify the most context-relevant affirmative action measures and to develop theoretical assumptions about the factors important for shaping candidates’ position-taking, such as gender, electoral success and party affiliation. Adopting a reserved-seat quota requires legal reform, and most often an elaborate and costly implementation process. We argue that gender is less important than assumed in the literature on position-taking because reserved seats are not perceived to pose a threat to male politicians’ positions in Zambia's current political system. Furthermore, both men and women are likely to resort to strategic reasoning based on their own electoral success and the role of the governing party when they make their choices. For successful women, who managed to win political office in the current system, the adoption of reserved seats could potentially lead to status-devaluation and openly supporting the measure could negatively affect their relationship with party gatekeepers.

Our findings indicate that party affiliation matters for policy positioning on a gender equality issue in the African context. While electoral candidates may not provide ideological cues or structure their political attitudes according to identifiable positions (Conroy-Krutz & Lewis Reference Conroy-Krutz and Lewis2011), our findings lend support to research showing that position-taking is affected by party characteristics, even in a context in which parties struggle with establishing themselves as credible ‘issue-owners’ (Bleck & van de Walle Reference Bleck and van de Walle2011).

A key contribution of this study is to shed light on why individual electoral success and party allegiance is equally important as gender as an explanatory factor for support of affirmative action in Africa. As argued by Brader et al. (Reference Brader, Tucker and Duell2013: 1490), opposition status does not necessarily render a party's program any clearer, but opposition members are ‘freed from the burdens of implementation’. In contrast, those affiliated with governing parties have less room to manoeuvre because they are held more accountable for the implementation of their campaign promises (Klüver & Spoon Reference Klüver and Spoon2016; Romeijn Reference Romeijn2020). Our reasoning also offers an explanation to Clayton et al. (Reference Clayton, Josefsson, Mattes and Mozaffar2019) who, in their cross-national study of African parliamentarians, find that ruling party MPs in Africa are significantly less likely to list political rights as a legislative priority. Government parties need to be more concerned with the implementation of policy positions, and those aligned with government parties have to be more careful with making promises on behalf of the party. One future research step could be to also test the degree of commitment of those aligned to ruling parties.

The implication of our findings is that women who find themselves in position to act for women, as they are aligned with the governing party, have either learnt from experience that radical position-taking equals trouble or were not really the most progressive at the outset. We cannot tell from our data whether it is the voters who prefer more moderate candidates or whether adopting less progressive views is an acquired post-election skill for both genders. Studies that trace how candidates’ positions change over time could be interesting in order to understand why there are not more women claiming radical change.

The main limitation of our study is that the list of alternative gender-equality measure options is not exhaustive and can be criticised for either being too broad or too narrow. We chose the options we identified as being most known among the candidates standing for elections in 2011, although including other kinds of affirmative action options possibly could have yielded a different result. Yet, the strength of our research design is that we are not assuming that all measures to promote women in politics will be similarly rejected or accepted by certain groups of respondents. A crucial direction for future research is to pay more attention to who favours different types of gender-equality solutions, including their knowledge about these solutions. We find that while scholars’ knowledge about different quota options is getting more sophisticated, policymakers are not nearly as familiar with the limitations of certain types of gender quotas in particular institutional settings. This is an area worthy of future research – critical party actors as well as office holders and women activists do not know the finer details of what is required to accomplish gender parity in elected or appointed office through these kinds of mechanisms. We thus call for more research into what works where, rather than reducing questions of gender quota adoption to a matter of rejecting or accepting the overall idea of affirmative action.