Introduction

Many commentators predicted that the COVID-19 pandemic would lead to a profound shift in the public’s social policy attitudes (Duncan, Reference Duncan2022). A notable focus has been the potential effect on welfare attitudes, particularly concerning working-age unemployment benefits (Lunt and Patrick, Reference Lunt and Patrick2020; Burchardt, Reference Burchardt2020).

Given the scale of changes to employment caused by the pandemic, national welfare systems were at the forefront of most countries’ COVID-19 response. The pandemic therefore represents a unique test of theories of welfare attitude formation and change.

Two bodies of theory and research offer contrasting predictions. The first encompasses a set of mechanisms leading us to expect increasing generosity in response to the pandemic. These include: (i) an increase in the perceived deservingness of claimants; (ii) a substantial expansion of direct and indirect experience of the welfare system (Edmiston et al., Reference Edmiston, Baumberg-Geiger, de Vries, Scullion, Summers, Ingold, Robertshaw, Gibbons and Karagiannaki2020); and (iii) an increase in generalised solidarity and pro-social attitudes (Sorell et al., Reference Sorell, Draper, Damery and Ives2009).

The second, opposing set of mechanisms emerge principally from research on the effects of previous financial crises and downturns, and include: (i) an increase in personal and public financial strain fostering austerity, self-interest and resentment (Uunk & van Oorschot, Reference Uunk and van Oorschot2019; Burchardt, Reference Burchardt2020; Roosma, Reference Roosma, Laenen, Meuleman and van Oorschot2020); and (ii) thermostatic effects, by which public attitudes become less generous in response to increasingly generous government policy (Wlezien, Reference Wlezien1995).

In this study, we examined the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on welfare attitudes in the UK using a unique combination of data sources. We combined: (i) temporally fine-grained data on attitude change over the pandemic period with; (ii) a novel nationally representative survey exploring more detailed attitudes about welfare claimants. Our findings suggest that the pandemic did prompt an increase in generosity and solidarity in welfare attitudes, but that that this effect was restricted to claimants who had lost jobs specifically due to the pandemic. Broader welfare attitudes were left relatively untouched. This finding of strong ‘COVID exceptionalism’ (Summers et al., Reference Summers2021), has significant implications – both for our understanding of the specific effects of the pandemic, but also more broadly for understanding the attitudinal effects of other large-scale events and crises.

An expectation of more generous welfare attitudes

As we have noted, there are broadly three mechanisms that would lead us to expect a positive effect of the pandemic on the generosity of welfare attitudes. The first is an increase in the perceived deservingness of claimants. According to the CARIN model of deservingness (van Oorschot & Roosma, Reference van Oorschot, Roosma, Van Oorschot, Roosma and Meueleman2017), the extent to which claimants are perceived as deserving reflects a mixture of their perceived Control (or blameworthiness), Attitudes (e.g. gratitude), Reciprocity (having paid into the system), Identity (are claimants ‘one of us’?) and Need (how much genuine hardship claimants would endure without help). It is often argued that claimants will be seen as more deserving during economic crises – partly due to identity (middle-class claimants become more common), but primarily because crisis-era claimants are seen to have less control over their situation (Uunk & van Oorschot, Reference Uunk and van Oorschot2019; Roosma, Reference Roosma, Laenen, Meuleman and van Oorschot2020). The latter effect was likely to be extremely strong during the early pandemic, as large swathes of the economy were required to cease activity for the public good. Perceptions of deservingness also depend on media coverage and political rhetoric (although to a debated extent; Baumberg et al., Reference Baumberg, Bell and Gaffney2012). In the UK, the focus of the present study, these appear to have been unusually positive during COVID (e.g. BBC News, 2020; Sandhu, Reference Sandhu2021).

The second mechanism potentially increasing generosity is a substantial broadening of the population directly or indirectly exposed to the welfare system. In the UK, the proportion of the population claiming out-of-work benefits rose dramatically during the pandemic (Department of Work and Pensions, 2021). Attitudes may have become more generous among those who found themselves claiming, and among family and friends (Hedegaard, Reference Hedegaard2014). Beyond this population of new claimants, large numbers of people also experienced a form of welfare through the furlough or Self Employment Income Support Schemes (SEISS), which replaced earnings for people who were employed but unable to work due to pandemic restrictions. Both schemes were administered outside the traditional benefits system – however this experience may have nevertheless increased empathy with conventional welfare claimants.

Even more broadly, many people who did not receive these forms of government support also experienced significant economic hardship, which may have increased support for social security (Margalit, Reference Margalit2013; Rees-Jones et al., Reference Rees-Jones, D’Attoma, Piolatto and Salvadori2021). Amongst non-claimants, perceived risk of claiming is also likely to have broadened (including to groups who had not previously thought of themselves as being potential claimants) – widening the constituency of people with a perceived stake in the benefits system (Rehm et al., Reference Rehm, Hacker and Schlesinger2012). Similar processes are also likely to have occurred in other countries.

Lastly, in many countries, including the UK, the pandemic appeared to prompt an increase in generalised social solidarity. In the UK, as elsewhere, the early pandemic saw large numbers of formal and informal support groups emerge (O’Dwyer, Reference O’Dwyer2022), alongside an apparent increase in generalised trust (Parsons & Wiggins, Reference Parsons and Wiggins2020), and a feeling that COVID-19 had increased people’s concern for each other (More in Common, 2020). It is plausible that such an increase in general social solidarity would increase support for the welfare state (Burchardt, Reference Burchardt2020). However, more recent evidence has found that, across Europe, generalised trust did not increase between 2020 and 2021 (Genschel et al., Reference Genschel, Hemerijck, Russo and Nasr2021), and that pro-social policy preferences remained highly conditional, rather than becoming more universal (Gandenberger et al., Reference Gandenberger, Knotz, Fossati and Bonoli2022).

Countervailing mechanisms

We have described three plausible mechanisms by which the pandemic may have increased public support for working-age welfare. However, there are also countervailing currents which may match or overwhelm these effects. First, individual and societal financial strain and insecurity can foster austerity, self-interest and resentment (Hoggett et al., Reference Hoggett, Wilkinson and Beedell2013; Uunk & van Oorschot, Reference Uunk and van Oorschot2019; Burchardt, Reference Burchardt2020; Roosma, Reference Roosma, Laenen, Meuleman and van Oorschot2020). Second, previous research has shown that when policy becomes substantially more generous (for example when public spending in a given area increases), public attitudes move thermostatically in favour of increasing austerity (Wlezien, Reference Wlezien1995). Therefore, as welfare support became more generous during the pandemic, the public’s appetite for such support may have correspondingly declined (Curtice et al., Reference Curtice, Abrams and Jessop2020).

In practice, many studies have shown that recessions and economic crises do not necessarily make welfare attitudes more generous (Kenworthy & Owens, Reference Kenworthy, Owens, Grusky, Western and Wimer2011; Uunk & van Oorschot, Reference Uunk and van Oorschot2019; Roosma, Reference Roosma, Laenen, Meuleman and van Oorschot2020). For example, in the UK, the Great Recession was followed by more negative rather than positive welfare attitudes (Taylor-Gooby, Reference Taylor-Gooby2013). This decline in public support may be a consequence of these countervailing mechanisms at work – pushing attitudes in the opposite direction to the likely increases in the perceived deservingness of claimants (Erler, Reference Erler2012).

Conditional solidarity – COVID exceptionalism

One possibility is that the nature and extent of attitude change in response to a crisis will result from a simple contest between the mechanisms described above. For example, if the perceived deservingness of claimants becomes very high (as appears likely during the pandemic), it may overwhelm any thermostatic or financial strain effects – resulting in more generous attitudes. Conversely, if financial strain becomes very acute, it may overmatch the forces promoting greater generosity.

Another possibility, however, is that attitude change does not arise from a simple combination of these forces, but is instead heavily context dependent. In particular, claims during a crisis may be seen as exceptional. Claimants who are perceived to be in need due to the crisis may be viewed more positively (as less blameworthy and more ‘like us’). However, these perceptions of increased deservingness may not extend to the broader body of claimants, limiting the effect of the crisis on overall attitudes. This is consistent with Erler’s (Reference Erler2012) analysis of US newspaper reporting during the 2008–2009 financial crisis. She found that people in poverty were represented as more deserving during this period, but that this was often explicitly contrasted with ‘normal’ poverty. She concludes: ‘The discourse that emerged reified class differences by portraying the “newly poor” as fundamentally different and more deserving of policy action than those who were in poverty prior to the economic crisis’ (Erler, Reference Erler2012, p185).

The COVID-19 pandemic offers a unique testbed for these competing theories. Given the unprecedented nature of the crisis, the mechanisms driving increasing generosity may be expected to ‘win out’. However, if COVID claimants are mentally bracketed away from conventional welfare claimants – what we term here as COVID exceptionalism – then this effect may be substantially muted, or even reversed.

The emerging evidence (and its limits)

At the time of writing, seven studies have examined changes in welfare and related attitudes in Europe over the course of the pandemic. None have found attitudes to have become more generous. In a two-wave panel study in Germany, Spain and Sweden, Ares et al. (Reference Ares, Bürgisser and Häusermann2021) found no change between 2018 and June 2020 in preferences for welfare retrenchment. Using a different measure from the same study, Enggist et al. (Reference Enggist, Pinggera and Häusermann2021) found a small increase in support for more generous unemployment benefits in Sweden, but no change in Spain or Germany. In Germany specifically, Lohman and Wang (Reference Lohmann and Wang2022) found no increase in welfare support in the early stages of the pandemic, and Bellani et al. (Reference Bellani, Fazio and Scervini2021) found that preferences for redistribution appeared lowest when the COVID crisis was most severe.

In the Netherlands, Reeskens et al. (Reference Reeskens, Muis, Sieben, Vandecasteele, Luijkx and Halman2021) found that support for state intervention to prevent poverty had declined between 2017 and May of 2020. Similarly, in the UK, people in July 2020 were slightly more likely than in 2019 to agree that ‘if welfare benefits weren’t so generous, people would learn to stand on their own two feet’ (Curtice et al., Reference Curtice, Abrams and Jessop2020). A further UK study found no evidence that the pandemic had affected attitudes towards taxation, spending or redistribution (Blumenau et al., Reference Blumenau, Hicks, Jacobs, Matthews and O’Grady2021).

Despite the relative consistency of these findings, there are a number of caveats that limit the conclusions we can draw. First, four of the seven studies examined only two time points – one prior to the pandemic and one during (Curtice et al., Reference Curtice, Abrams and Jessop2020; Ares et al., Reference Ares, Bürgisser and Häusermann2021; Enggist et al., Reference Enggist, Pinggera and Häusermann2021; Reeskens et al., Reference Reeskens, Muis, Sieben, Vandecasteele, Luijkx and Halman2021). This prevents us from observing potentially substantial attitude shifts in response to a rapidly evolving situation (for example, movements in and out of national lockdowns). Bellani et al. (Reference Bellani, Fazio and Scervini2021) and Blumenau et al.’s (Reference Blumenau, Hicks, Jacobs, Matthews and O’Grady2021) work did cover several points during the pandemic; however, both studies examined more general attitudes towards taxation and redistribution, rather than welfare attitudes specifically.

Second, face-to-face pre-pandemic surveys were forced online during COVID-19 (Curtice et al., Reference Curtice, Abrams and Jessop2020), potentially hampering comparability between time points (Atkeson et al., Reference Atkeson, Adams and Alvarez2014).

Third, and most importantly, none of the previous studies asked directly about perceptions of the COVID-19 wave of benefit claimants. This prevents any direct investigation of COVID exceptionalism.

Our study makes a unique contribution by responding to all three limitations. Our analysis begins by attempting to establish whether and how welfare attitudes in the UK changed over the course of the pandemic – employing nationally representative data collected every two months using a consistent survey mode:

RQ1: How did general welfare attitudes in the UK change at the outset of the pandemic, and how did they evolve over time?

We then use data from a novel survey to compare attitudes towards COVID versus pre-pandemic claimants, and to explore the possibility of COVID exceptionalism.

RQ2a: Were COVID claimants (those who began claiming during the pandemic) perceived to be substantially more deserving and less blameworthy than pre-pandemic claimants?

RQ2b: In what other ways, if any, were COVID claimants perceived to be different to pre-pandemic claimants?

RQ3: To what extent have differential perceptions of COVID versus pre-pandemic claimants affected trends in overall welfare attitudes?

Methods

Tracking attitudes across the pandemic

To address RQ1 we used data from YouGov’s Welfare Tracker 2019–2022 – a series of repeated cross-sectional surveys of welfare attitudes, conducted online approximately every eight weeks. The surveys include 1,600 to 1,700 responses per wave. Here we analyse twenty-one waves of data (40,817 responses) from June 2019 to July 2022.

YouGov recruit participants for the Welfare Tracker surveys from their opt-in panel. To create nationally representative estimates, YouGov select panel members to match known UK population totals in terms of age, gender, National Readership Survey Social Grade and education. Data are then weighted according to the same characteristics, plus the party respondents voted for at the previous national election, their vote in the Brexit referendum, and their level of political interest.

There are limitations to this survey method. For example, non-response in opt-in panels resulted in prediction errors for the UK 2015 General Election (Sturgis et al., Reference Sturgis, Baker, Callegaro, Fisher, Green, Jennings, Kuha, Lauderdale and Smith2016: 67) (although YouGov has performed well in predicting election results since this date). Moreover, the YouGov panel (like other online panels) likely under-represents those with weaker English language and digital skills, or with online access issues. If the attitudes of these groups differ sufficiently from those who are included, this may bias our findings in unknown directions. However, our analysis of this data focuses principally on changes over time, and to this end, online surveys allow for consistency in terms of survey mode and sample, improving over-time comparability.

To examine trends in welfare attitudes over the course of the pandemic, we selected two measures capturing key policy-related attitudes. The first captures perceptions of the deservingness of claimants:

Thinking about people who receive welfare benefits, including disability benefits, out of work benefits and benefits to support people in low paying work, what proportion of people receiving benefits do you think are genuinely in need and deserving of help?

-

1. All or almost all people who receive benefits are genuinely in need and deserving of help

-

2. The majority of people…

-

3. Around half of people…

-

4. Only a minority of people…

-

5. Hardly anyone…

The second captures support for more/less generous benefits:

And thinking about the level of benefits, do you think they are too high, too low, or is the balance about right?

For the purposes of analysis, we dichotomised responses to both questions, contrasting: (i) respondents who thought that half or fewer claimants were deserving; and (ii) those who thought benefits were too high with all other valid responses. These dichotomous variables are therefore measures of anti-welfare sentiment.

Unpacking attitudes towards COVID and pre-pandemic claimants

To address RQ2a, RQ2b and RQ3 we commissioned YouGov to conduct a novel survey.Footnote 1 This was conducted online in May – June 2021 and included a sample of 3,429 people, recruited through YouGov’s online panel (see above). Ethical approval for the survey was given by the University of Salford. The full dataset and questionnaire are available through the UK Data Service (SN6989) (this excludes the free-text responses described below to ensure participant anonymity).

In this survey we took four approaches to comparing public attitudes to COVID versus pre-pandemic claimants. First, we asked respondents directly about differences in deservingness between COVID-19 and pre-pandemic claimants (adapting the wording of the YouGov welfare Tracker question described above):

Compared to people who were claiming benefits before COVID-19 (i.e. before March 2020)…

Do you think that people that claimed welfare benefits during COVID-19 were more likely to be in need and deserving of help, or less likely, or about the same?

Responses were given on a five-point scale from Far more… to Far fewer people who claimed during COVID-19 were genuinely in need and deserving of help.

Second, we focused specifically on the extent to which participants felt that COVID/pre-pandemic claimants were to blame for their circumstances. To investigate this in more detail, we looked at both blame for losing a job (retrospective blame), and blame for being unable to find a job and leave benefits (prospective blame). Respondents were randomly assigned to see either the retrospective or prospective version:

On average, how much do you think each of the following groups are to blame for [losing their jobs/being unable to get a job and leave benefits]?

1. People [who lost their job/on benefits and unable to get a job] before Covid-19 (before Feb 2020)

2. People [who lost their job/on benefits and unable to get a job] during Covid-19 (since Mar 2020)

In both cases, response options were that most/about half/a minority/very few are to blame. Note that this measure asks about COVID-19 and pre-pandemic claimants separately, thereby allowing us to determine absolute as well as relative perceptions of blame.

Third, to address the possibility of social desirability bias, we included a vignette experiment at the end of the questionnaire (after several unrelated questions). In this vignette a hypothetical claimant was randomly described as either claiming benefits: (i) before the pandemic (in 2019); or (ii) during the pandemic (in 2020). In both cases, the claimant was described as having been out of work for three months, beginning in April and ending in July. An example full-text of the vignette is given below:

John is a 35-year-old man living in England. In April 2019, before the COVID pandemic, John’s company went bust and John lost his job. John then started claiming Universal Credit, and three months later (in July 2019, before the COVID pandemic), had not been able to get a job.

Do you think John is to blame for being out of work three months later (in July 2019, before the COVID pandemic)?

As well as varying the time period, we also varied the claimant’s age (35–60) and name (to indicate gender) (John/Liz). We also randomly varied whether we provided an explanation for job loss (‘John/Liz’s company went bust and John/Liz lost his/her job’ versus ‘John/Liz lost his/her job’). This latter manipulation allowed us to determine whether vaguely described claimants were subject to greater COVID-19 effects than those who were explicitly cued as having lost their job for a reason outside their control. In total we therefore manipulated four elements of the vignette, with each element having two possible states – yielding sixteen possible unique vignettes.

Analysis of free text responses

We gathered qualitative data on perceptions of COVID-19 versus pre-pandemic claimants by asking the following free text question:

What do you think are the main differences between people claiming benefits before COVID-19 and people claiming during COVID-19, if any?

There are broadly two approaches to analysing free text survey responses. The first is to manually code responses, according to an inductively derived thematic framework. This produces theoretically relevant, interpretable findings, but prompts inevitable questions of subjectivity. The second approach is to use automated procedures – often based on machine learning – to identify patterns within the data. Automated procedures are less likely to be biased towards researchers’ prior expectations, but often produce results that are more difficult to interpret. Here we use both techniques to triangulate our findings.

The thematic coding involved manually reviewing responses to identify the individual themes respondents raised. Responses were reviewed until topic saturation. This process yielded a total of seven higher-order themes and fourteen sub-themes, which were used as the basis of a coding scheme (a full description of the coding scheme is given in Web Appendix A). All 3,476 responses were reviewed and assigned thematic codes (each response could contain multiple themes). Two study authors independently coded 2,267 responses each, including an overlap sample of 529 responses to check levels of agreement. Inter-rater agreement was high: 95+% at the code level, and 82% for agreement on all codes for a response.

Our automated process applied Structural Topic Models (STMs) using the STM package in R. STMs are used to identify patterns in corpora of text documents (including free text survey responses) (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Stewart, Tingley, Lucas, Leder-Luis, Kushner, Albertson and Rand2014). The STM inductively groups these responses into topics through a machine-learning procedure. Similar responses using overlapping sets of words are grouped together under the same topic, whereas responses using dissimilar words are grouped under different topics. After excluding ‘don’t knows’ and ‘no difference’ responses (determined during manual coding), we applied our topic model to the remaining responses (N = 2,018). After examining model fit statistics and manually inspecting exemplar responses, we determined that a seven-topic solution was most informative. Further details on the STM procedure are given in Web Appendix B.

Results

Attitudes across the pandemic

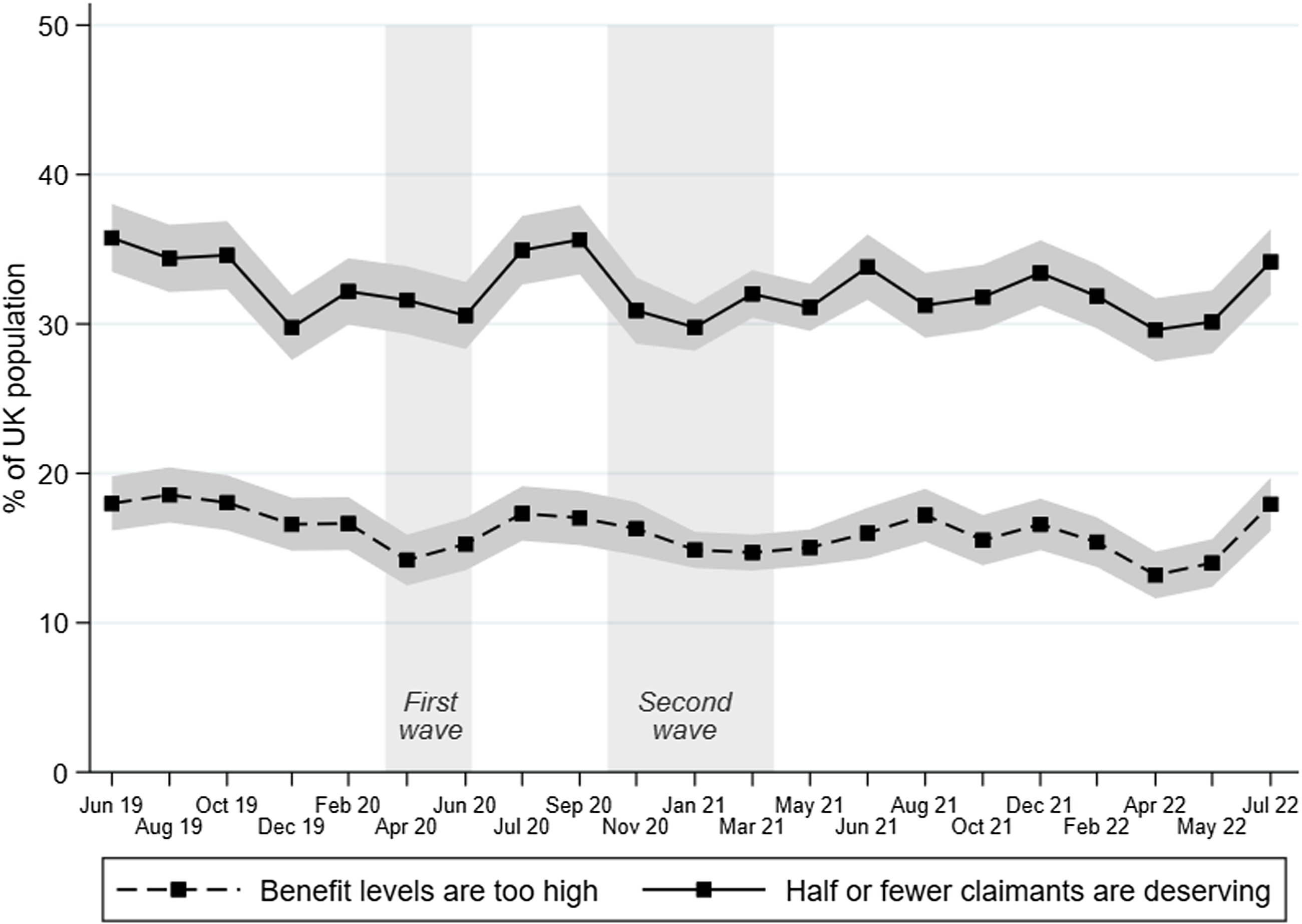

Figure 1 shows the trends in our two selected attitude measures from June 2019 through July 2022. To contextualise the trends, we have indicated two waves of the pandemic in the UK, based on the intensity of national restrictions. We define the first wave as running from 16 March 2020 (when the Prime Minister declared ‘now is the time for everyone to stop non-essential contact and travel’) to 15 June 2020 (when non-essential shops were allowed to re-open). We define the second wave as running from 14 October 2020 (when a regional Tier system of restrictions was introduced) to 29 March 2021 (when the Tier system was relaxed and replaced with a rule limiting indoor social gatherings to six people).Footnote 2

Figure 1. Trends in anti-welfare attitudes 2019–21, from YouGov Welfare Tracker surveys (total N=40,817).

Figure 1 suggests that the pandemic did not prompt a substantial shift in welfare attitudes. Both waves of the pandemic do appear to coincide with a slight decline in anti-welfare sentiment. However, these declines are followed by a reversion to pre-pandemic levels. It is also notable that the period February-April 2022 saw similar declines in anti-welfare attitudes to the first wave of the pandemic, despite no equivalent resurgence of the disease.

We further explored trends in our selected attitude measures by combining responses from the individual surveys into five separate periods:

-

Pre-pandemic: data collected prior to 16 March 2020 (N = 8,464)

-

First wave: data collected 16 March 2020 to 15 June 2020 (N = 3,237)

-

Summer 2020: data collected 15 June 2020 to 14 October 2020 (N = 3,286)

-

Second wave: data collected 14 October 2020 to 29 March 2021 (N = 8,264)

-

After second wave: May 3 2021 to 22 July 2022 (N = 17,566)

We used linear probability models (Battey et al., Reference Battey, Cox and Jackson2019) to compare responses to each measure across the five periods. These models regressed each measure on a dummy variable for the relevant contrast, with respondents from other periods excluded.Footnote 3 Table 1 shows the percentage point change in responses between these time periods, along with 95% confidence intervals for each contrast:

Table 1. Change in anti-welfare attitudes between time periods (percentage point change with 95% confidence intervals)

YouGov welfare tracker surveys (total N = 40,817).

Table 1 shows that, according to both measures, attitudes during the first wave of the pandemic were significantly less anti-welfare than during the pre-pandemic period. However, during the summer of 2020, attitudes rebounded to become significantly more anti-welfare than during the first wave.

Attitudes during the second COVID-19 wave were more generous than those during summer 2020 (although the change for the benefit levels question is more tentative). Attitudes after the second wave (i.e. in May 2021) did not differ significantly from attitudes during the second wave.Footnote 4

Comparing the data collected after the second COVID wave with the pre-pandemic period shows that the public had become less anti-welfare over the course of the pandemic. However, this difference was very small – around two percentage points on both measures.

To put these changes into context, we compared the data analysed above with data from a nationally representative YouGov survey conducted in April 2013. In this survey (N = 1,991), YouGov asked respondents about benefit levels using the same measure we employ above (are benefit levels too high/too low/about right). In the 2013 survey, 37.3% (95% CI: 34.7% to 40.1%) of respondents thought that benefits were too high – compared with the 17.8% who said the same in the pre-pandemic period. This difference of 19.5 percentage points is almost ten times as large as the total difference we observe between the pre-pandemic and post wave 2 surveys.

These results suggest that the pandemic prompted very little change in general welfare attitudes. Is this because attitudes towards COVID-era claimants were – contrary to expectations – not substantially more benign than attitudes towards pre-pandemic claimants? Or might substantially more generous views of the former group have failed to generalise to claimants more broadly, thereby blunting any effect on general welfare attitudes (i.e. COVID exceptionalism)?

Were COVID claimants viewed more positively than pre-pandemic claimants?

Were COVID claimants seen as more deserving?

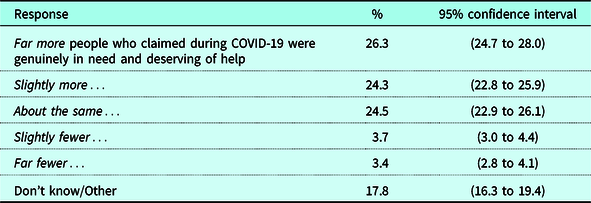

Table 2 gives respondents’ views on whether COVID or pre-pandemic claimants were more likely to be genuinely in need and deserving of help. Half of respondents thought that COVID claimants were more likely to be deserving, compared with around a quarter who though that the two groups were equally likely to be deserving. Only a small minority (7.1%) felt that COVID claimants were less likely to be deserving.

Table 2. Were COVID claimants perceived as more likely than pre-pandemic claimants to be genuinely in need and deserving of help?

WASD general population survey May/June 2021, n = 3,476.

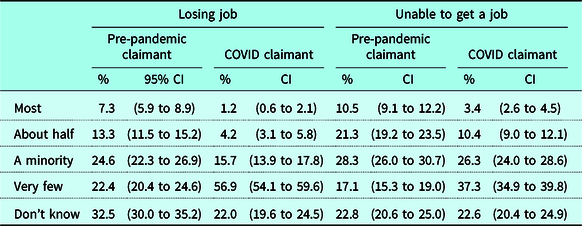

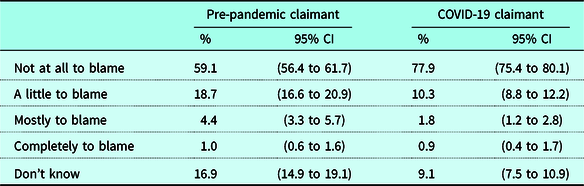

Were COVID claimants considered less blameworthy?

Table 3 gives the breakdown of responses to the separate survey items assessing the perceived blameworthiness of COVID and pre-pandemic claimants for losing their jobs/being unable to get a job and leave benefits. Only 5.4% of respondents felt that half or more of COVID-19 claimants were to blame for losing their jobs. By contrast, the figure for pre-pandemic claimants was 20.5% – a 15.1 percentage point difference (95% CI: 12.4 to 17.7 pp). Similarly, 13.8% of respondents thought that half or more of COVID claimants were to blame for being unable to find a job, compared to 31.8% who said the same about pre-pandemic claimants – an 18.0 percentage point difference (95% CI: 15.0 to 21.0 pp).

Table 3. Were COVID claimants perceived as more likely than pre-pandemic claimants to be to blame for losing their job/being unable to get a job and leave benefits?

WASD general population survey May/June 2021, split ballot (N for losing job = 1,704, N for remaining unemployed = 1,772).

Table 4 gives the breakdown of responses to the vignette experiment. Consistent with the results reported above, respondents who read about a COVID claimant were 18.8 percentage points more likely to consider the claimant to be entirely blameless (95% CI: −22.3 to −15.2 ppt). However, it is notable that in both versions of the vignette a clear majority of respondents felt that the hypothetical claimant was blameless.

Table 4. Were vignette claimants who lost their jobs during COVID perceived to be less blameworthy?

WASD general population survey May/June 2021, n = 3,480.

Examining the other randomised elements of the vignette, we found that respondents did not see young claimants, male claimants, or claimants who had lost their jobs due to the closure of their employer (versus no explanation given) as more or less blameworthy.

In order to determine whether differential perceptions of COVID versus pre-pandemic claimants were moderated by other claimant characteristics, we ran logistic regression models separately interacting the COVID-versus-pre-pandemic variable with claimant age, gender and whether the claimant’s job loss was explicitly attributed to the closure of their employer. We found no significant moderating effect of any of these factors. This ran counter to our expectation that pre-pandemic claimants would be perceived more similarly to COVID claimants if an exonerating reason for their job loss was given.

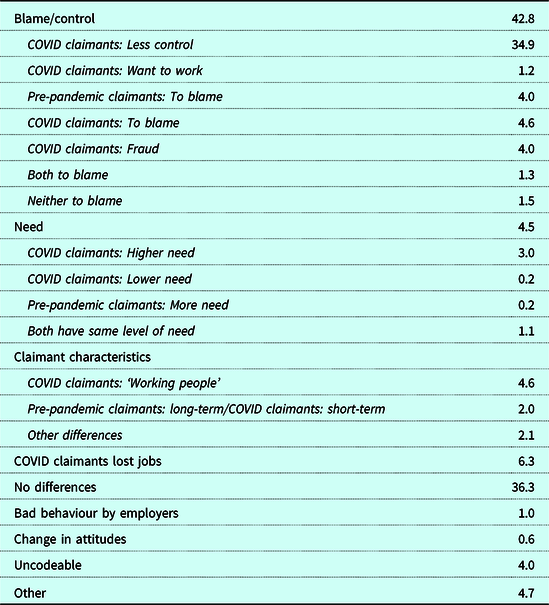

How did perceptions of COVID versus pre-pandemic claimants differ? Analysis of free text responses

In response to our free text question, 15% of respondents gave some version of a ‘don’t know’ or other non-response. These respondents were excluded from our manual thematic analysis. Within the remaining responses, 36% explicitly stated that there were no differences between COVID and pre-pandemic claimants. This was retained as an individual theme in our thematic analysis (see Table 5). However, these responses were excluded from our STM analysis because the sentiment almost always appeared alone as a single statement and could therefore be separated from the other texts manually.

Table 5. Results of the manual thematic analysis: % of responses containing each theme and sub-theme

WASD general population survey May/June 2021, n = 2,906.

The most common themes in both methods of analysis related to blame/control. Respondents discussed the control that COVID and/or pre-pandemic claimants were perceived to have over their situation, and hence (implicitly or explicitly) the extent to which they should be blamed for claiming. Almost half (43%) of all responses referenced levels of blame/control among claimants. Of this 43%, the vast majority (35% of all responses) suggested that COVID claimants had less control over their circumstances and were therefore (implicitly or explicitly) less blameworthy in their need to claim government assistance. Example responses include:

Some people only lost their job because COVID caused the company to shut down.COVID was a terrible disaster and so many people lost their jobs. It’s obviously not their fault.

Note that we took a conservative approach in the thematic analysis, and excluded from this code responses which mentioned COVID-era job loss, but without explicitly indicating COVID as the cause (e.g. ‘more during the pandemic had lost jobs’”). Responses of this kind were coded as ‘COVID claimants lost jobs’.

A corollary theme was that pre-pandemic claimants were to blame for their circumstances (4% of all responses). This theme could appear alone (e.g. ‘ A majority of people claiming before COVID did not want to work for a living’). However, it appeared most commonly in comparative statements such as ‘ Many people lost income during the pandemic through no fault of their own and had to claim benefits. Many people before the pandemic were claiming benefits because they were choosing not to work’.

Similarly, in the STM results, the most common topics (Topics 6 and 7, which together covered 33% of responses) drew together responses incorporating the Blame/Control theme. In particular, responses under Topic 6 (14% of responses) focused on COVID claimants’ perceived willingness to work, whereas pre-COVID claimants were more likely to be identified as people who ‘did not want to work’. Some responses under Topic 7 (19% of responses) also noted that COVID claimants had a ‘genuine reason to claim’ because they had lost their jobs ‘through no fault of their own’. Similar themes also appeared in Topics 2 and 4 (28% of responses), which distinguished COVID and pre-pandemic claimants implicitly by describing the devastating impact of the pandemic on job availability (a ‘naturally caused event’ that caused ‘absolute devastation’).

Around 5% of respondents made the opposite case – that COVID claimants were culpable for their claim. This was most commonly linked with the idea of fraud – with COVID claimants seen as potentially exploiting lax oversight to claim benefits they were not entitled to (e.g. ‘Some people claimed as a scam because it was made easier’). This was less clearly seen in the STM analysis, but within Topic 5 (15% of responses) there were many responses that emphasised the potential for fraud among both pre-pandemic and COVID claimants.

Finally within the higher order theme of blame/control, a small number of responses (around 3%) argued that COVID and pre-pandemic claimants were equally blameworthy, either because both were at fault (e.g. ‘They are both scroungers’), or because neither were (e.g. ‘Nothing. They are equally impoverished through no fault of their own’).

Themes relating to potential deservingness criteria other than blame/control were much less common. Only 5% of responses referenced levels of need among claimants. Predominantly (3% of all responses), these responses focused on potential reasons for increased need among COVID claimants, most commonly due to an unexpected loss of earnings combined with higher outgoings (e.g. ‘During COVID-19 those who had to start claiming because they could not work…would probably have taken on more commitments (e.g. mortgage) than those already claiming benefits so would struggle’). The STM results also grouped together responses which discussed changing income and living standards, with Topic 3 (12% of responses) tending to emphasise the challenge of living on benefits, and responses under Topic 1 (12% of responses) focusing on the sudden loss of income experienced by many COVID claimants.

A separate set of responses (8% of respondents) referenced claimant characteristics which did not fall under the higher order themes of need or blame/control. Most commonly, these responses focused on the idea that COVID claimants were ‘working people’ who had previously held ‘stable’ jobs. Implicit (and often explicit) in these responses was the idea that pre-pandemic claimants were likely to have ongoing ‘issues’ – such as disability, low education, or lack of motivation – which led them to frequently claim benefits. By contrast, COVID claimants were described as essentially ‘hard-working’ people who likely ‘never expected’ to claim benefits, and who would resume work as soon as the crisis had passed. Example responses falling under this theme include:

People claiming before have probably been claiming for most of their adult lives and have no intention of ever working whereas people claiming during covid probably lost their jobs due to the pandemic and have worked most of their lives.

A lot of people claiming during Covid had good jobs and were hard working.

The STM identified similar views within the most popular topic (Topic 7, 19% of responses). However, as we saw above, it grouped these together with responses referencing COVID claimants’ lower levels of blame/control. This is a case in which these themes are clearly linked (and indeed were often raised together in the same response). However, we felt it helpful to separate them conceptually in our manual analysis due to their differing focus – with blame/control focusing on the circumstances of the claim, and claimant characteristics focusing on the nature of the claimant themselves.

Finally, Table 5 lists a small number of other themes (such as bad behaviour by employers), which were both relatively rare and are tangential to our focus here, and which we therefore do not discuss in-depth.

Taken together, these results support our quantitative findings in showing the clear distinctions many respondents drew between COVID and pre-pandemic claimants. Though around a third of respondents saw no differences between the two groups, many more identified COVID claimants as exceptional – either in the unprecedented circumstances of their claim, or in their nature as essentially ‘working people’ who would have never otherwise have needed to claim.

COVID exceptionalism and attitude stability across the pandemic

The results described above show that COVID claimants were considered substantially more deserving than pre-pandemic claimants. However, our analysis of trends in attitudes shows that a large influx of these ‘more deserving’ claimants did not produce a corresponding change in overall welfare attitudes. As we have proposed, a plausible explanation for this apparent contradiction is that COVID claimants are seen as exceptional, with perceptions of this exceptional group therefore having a muted effect on overall welfare attitudes.

We used data from our novel survey to investigate this possibility (RQ3). In this survey, we replicated one YouGov’s Welfare Tracker measures of general welfare attitudes: whether respondents felt that welfare benefits were too high, too low or about right. After dichotomising responses in the same way as described above, we conducted a logistic regression jointly predicting this outcome from our measures of the perceived blameworthiness of: (i) COVID claimants; and (ii) pre-pandemic claimants.

We found that respondents who saw pre-pandemic claimants as highly blameworthy (as compared with those who saw them as less blameworthy) had almost five times the odds of saying that benefits were too high (OR = 4.75, 95% CI: 3.65 to 6.17). Respondents who saw COVID claimants as highly blameworthy (as compared with those who saw them as less blameworthy) were also significantly more likely to say that benefits were too high; however, this effect was less than half as large (OR = 2.30, 95% CI: 1.68 to 3.15) (Wald p-value for contrast = 0.002). Hence, opinions on general benefit levels appeared much more strongly determined by perceptions of pre-pandemic claimants than by perceptions of COVID-19 claimants.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that the pandemic did not engender a meaningful increase in support for working-age unemployment benefits in the UK. This is consistent with previous evidence showing limited change in welfare attitudes in the UK (Curtice et al., Reference Curtice, Abrams and Jessop2020; Hicks, Reference Hicks2020), and elsewhere (Enggist et al., Reference Enggist, Pinggera and Häusermann2021; Reeskens et al., Reference Reeskens, Muis, Sieben, Vandecasteele, Luijkx and Halman2021). Our results, which are based on temporally fine-grained data collected using a consistent survey mode, considerably strengthen this body of evidence.

What explains this apparent stability (both in the UK, and further afield) in the face of an all-consuming collective crisis, accompanied by an unprecedented expansion of the welfare system? Our findings point to one potential explanation – what we term COVID exceptionalism (Summers et al., Reference Summers2021). If the new influx of claimants during COVID are considered sufficiently different from pre-pandemic claimants, then attitudes towards the former group may be mentally bracketed away from attitudes towards the latter. This is consistent with previous research on media coverage during recessions, in which recession-era claimants are portrayed substantially differently to conventional claimants (see Erler, Reference Erler2012). If general welfare attitudes (such as those we employ in our trend analysis, and which have been employed by other studies of the attitudinal effects of the pandemic) are more strongly determined by attitudes towards conventional claimants than by attitudes towards novel COVID claimants, then this presents one possible explanation for the attitudinal stability we and others have observed.

Our findings are consistent with this explanation. Responses to our quantitative and qualitative questions strongly suggested that COVID claimants were seen as categorically different to – and more deserving than – normal claimants. We also found that overall welfare generosity was much more strongly predicted by perceptions of the former than the latter.

An alternative explanation for attitudinal stability in the face of the pandemic is that mechanisms which would tend to make welfare attitudes more generous (an increase in the perceived deservingness of claimants, an expansion in indirect and direct experience of welfare, an increase in generalised solidarity) were equally matched by countervailing mechanisms making attitudes less generous: principally financial strain (Hoggett et al., Reference Hoggett, Wilkinson and Beedell2013; Uunk & van Oorschot, Reference Uunk and van Oorschot2019) and thermostatic responses (Wlezien, Reference Wlezien1995; Curtice et al., Reference Curtice, Abrams and Jessop2020).

Two factors militate against this explanation. First, it does not explain our finding of stability in overall measures of the perceived deservingness of claimants. One may expect self-interested austerity (or thermostatic responses) to reduce support for welfare spending. However, it does not seem a likely explanation for the mismatch between: (i) dramatically more sympathetic perceptions of COVID claimants; and (ii) a lack of reactivity in the perceived deservingness of claimants overall. Strong countervailing financial strain or thermostatic effects are also inconsistent with widespread support for pandemic-specific increases in welfare spending (YouGov, 2021). The British public were still willing to support increased welfare spending – so long as this spending was targeted at COVID-related claims.

These facts also contradict a ‘ceiling effect’ as a potential explanation for attitudinal stability – i.e. that the considerable softening of welfare attitudes in the UK over the last two decades left little scope for further movement in response to the pandemic. The substantially more benign attitudes our respondents displayed towards COVID claimants demonstrate that such movement was possible.

Given the evidence contradicting the counterbalanced forces and ceiling effect explanations, COVID exceptionalism appears to be the most plausible explanation for our findings. This adds to our existing understanding of the effect of the pandemic on welfare attitudes (Curtice et al., Reference Curtice, Abrams and Jessop2020; Ares et al., Reference Ares, Bürgisser and Häusermann2021; Blumenau et al., Reference Blumenau, Hicks, Jacobs, Matthews and O’Grady2021; Enggist et al., Reference Enggist, Pinggera and Häusermann2021; Reeskens et al., Reference Reeskens, Muis, Sieben, Vandecasteele, Luijkx and Halman2021). However, beyond the pandemic, it has significant implications for wider research on the effect of crises on social policy attitudes. If policy targets who are strongly connected to a specific crisis are seen as profoundly exceptional, then any effect of the crisis on overall attitudes may be muted. This may help to explain why previous economic crises have not resulted in more generous welfare attitudes (Kenworthy & Owens, Reference Kenworthy, Owens, Grusky, Western and Wimer2011; Taylor-Gooby, Reference Taylor-Gooby2013; Uunk & van Oorschot, Reference Uunk and van Oorschot2019; Roosma, Reference Roosma, Laenen, Meuleman and van Oorschot2020).

There is considerable scope for future work to investigate these more general implications. First, one of the limitations of the present study is its single country focus. UK welfare discourse is highly polarised (O’Grady, Reference O’Grady2022), and this may lead to more pronounced exceptionalism for deserving claimants. Research on this phenomenon-outside of the UK is therefore vital. A further limitation of the present study is that we have considered exceptionalism relatively loosely as being either present or absent. Future research could examine the extent of exceptionalism and the resulting implications for general policy attitudes. Does more pronounced exceptionalism lead to a more dramatic weakening of the link between attitudes towards crisis-related policy targets and more general attitudes? Such research could also usefully investigate how media and political actors shape the process of exceptionalisation. Is exceptionalisation principally a bottom-up process, driven by, for example, underlying logics of deservingness (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Slothuus, Stubager and Togeby2011); or is it strongly shaped by political and media narratives? Further research is needed to adjudicate between these alternatives.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279423000466

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editorial board of the Journal of Social Policy, and two anonymous reviewers for their very constructive feedback on this paper.

Funding statement

This paper arose from a project funded by UK Research and Innovation (Welfare at a Social Distance: Accessing social security and employment support during the COVID-19 crisis and its aftermath, ES/V003879/1).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethics approval statement

Ethical approval for this project was granted by the University of Salford.