I. Comparison of National Capacity on DHM in AMS Before and After the ARCH Project Implementation

A. Introduction

This study tries to capture the impact of the Project for Strengthening the ASEAN Regional Capacity on Disaster Health Management (ARCH Project) in each ASEAN Member State (AMS) as a result of the ARCH Project implementation since the initiation of the project in July 2016.1

The analysis is based on a comparison of the impact of the project on legislative and policy framework, training/education programs, management and coordination of Emergency Medical Teams (EMT), application of the project outcome in actual disaster/emergency operations, compared to the previous “pre-ARCH” status in each AMS, identified through a survey on the Situation of Disaster/Emergency Medicine System in the ASEAN Region that was conducted, prior to the formulation of the ARCH Project, from November 2014 to August 2015.2

The pre-project survey identified that it would be necessary to establish a coordination platform for information sharing, and develop common and minimum tools to coordinate medical response and rapid health needs assessment (HNA) in the affected areas. It was also emphasized that every country would need to fulfill a certain level of minimum standards both administratively and technically in order to apply the developed common tools.

B. Methodology

The necessary data and information to identify the current status “post-ARCH” in each AMS were mainly collected through a questionnaire survey on the impact of the ARCH Project. The survey was conducted from December 2020 to January 2021 with supplementary information from the needs and potential survey for capacity development of disaster health management (DHM) in AMS conducted from September 2019 to March 2021.3

C. Results: Impact of the ARCH Project Observed in AMS

1. Legislative and Policy Framework

As shown in Table1, the development of legislation or strategic plans related to DHM has been in progress in several AMS based on the knowledge and experience gained through the ARCH Project. In Cambodia and Lao PDR, recent incidents such as mass-casualty incidents (MCI) and heavy flooding after a dam collapse have led to an increased emphasis on DHM.

Table 1. National Legislation, Policy, and Strategy Developed/Amended since 2016

2. Training and Education Program

AMS have developed and organized short-term training courses in different areas of DHM, and common topics taken by all AMS are the MCIs and public health emergencies.

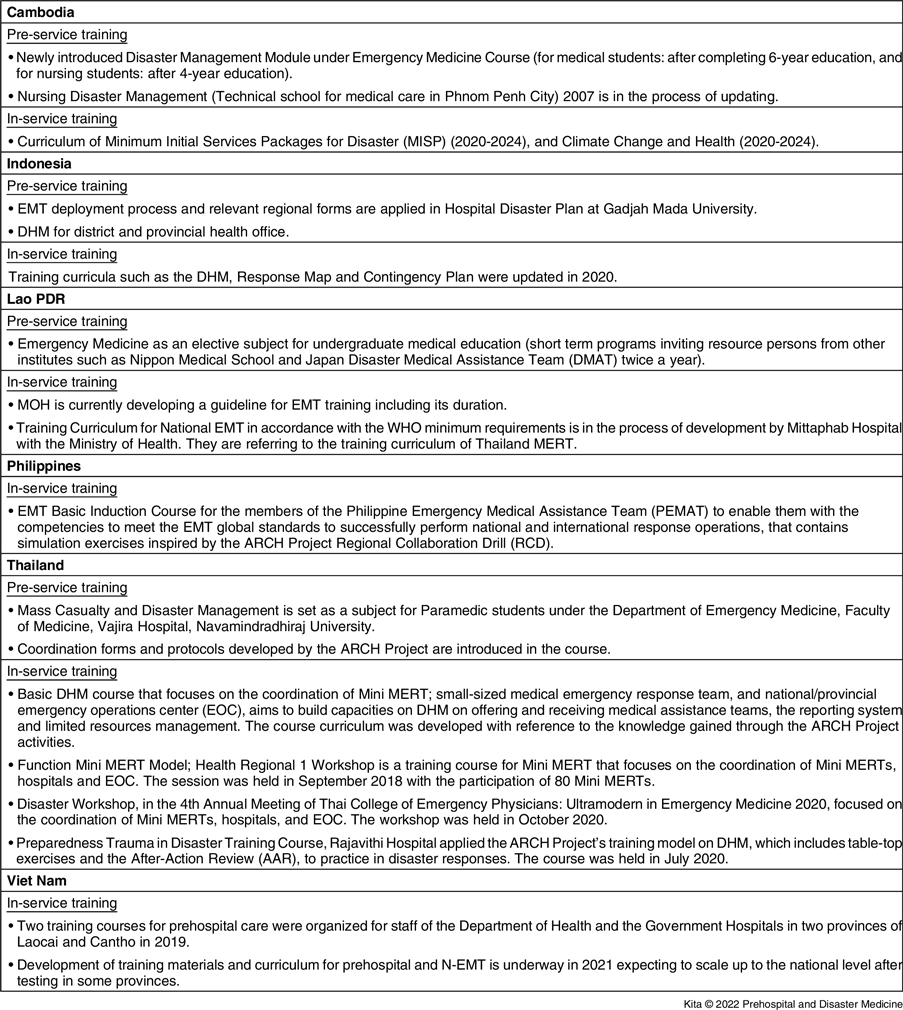

Many AMS indicated that support is required for the implementation of training of trainers (TOT) and standardization of the training curriculum for DHM. Table2 and Table3 indicate the list of training introduced or improved and relevant impacts observed through the implementation of the ARCH Project.

Table 2. Training or Education Program on DHM Introduced or Improved Since 2016

Table 3. Other Impacts Related to Training or Education on DHM

The methodology adopted in the ARCH Project events such as the simulation exercises of regional collaboration drill (RCD) has influenced several AMS in developing their training curricula, and Lao PDR has referred to the Thailand Medical Emergency Response Team (MERT) training example when developing its national EMT training curriculum.

3. Management of EMT and Coordination of EMTs

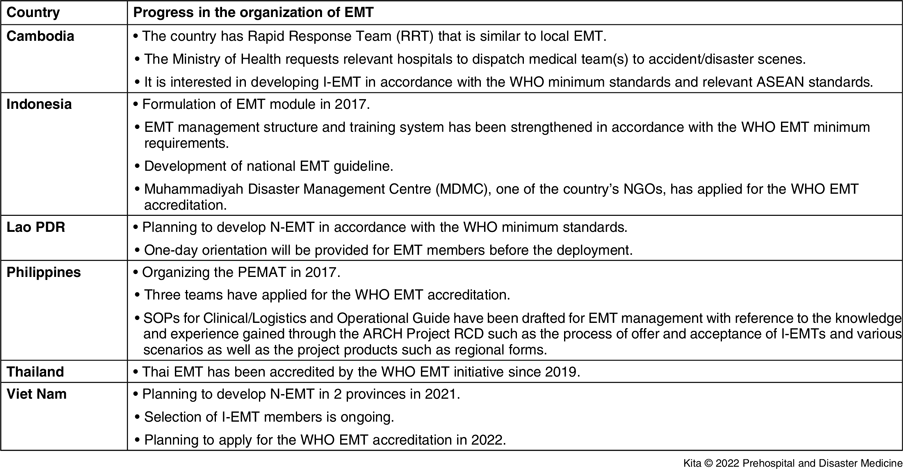

The national target set in the Plan of Action (POA) to realize the ASEAN Leaders’ Declaration on DHM requires AMS to develop the I-EMT that is compliant with either ASEAN or WHO I-EMT minimum standards and EMTCC standard.4,5

Table4 shows that Thailand EMT has been accredited by the WHO EMT initiative, while Indonesia and the Philippines are in the process, and Viet Nam has a plan to apply in future.

Table 4. Progress in the Management of EMT

Table5 indicates progress in developing EMT coordination mechanisms. Several countries have developed legislation or SOP to strengthen their EMT coordination capacity.

Table 5. Progress in Strengthening EMT Coordination Mechanism

4. Emergency Medical Operation in Actual Disaster/Emergency

Table6 indicates the application of the ARCH Project outcome in actual disasters/emergencies. As indicated in the Table, not only regional tools such as forms for Medical Record for Emergency and Disaster (MRED) or HNA, but also knowledge and experience obtained through the project activities have been used in real disaster/emergency response.

Table 6. Impact (Utilization of Outputs and/or Products) of the ARCH Project in Actual Disaster/Emergency Response

D. Summary of the Impact of ARCH Project to AMS

The ARCH Project developed a POA to realize the ASEAN Leaders’ Declaration on Disaster Health Management (POA/ALD on DHM). 4 This POA/ALD on DHM was later adopted by the ASEAN Health Ministers Meeting (2019, Cambodia), in which seven national targets including the development of I-EMT in accordance with ASEAN or WHO I-EMT minimum standards, the establishment of EMTCC, and development of a national procedure to receive international assistance, as well as the establishment of disaster health training systems, are set out for AMS to achieve.

Since the initiation of the ARCH Project in 2016, Thailand EMT has been accredited by the WHO EMT initiative, while Indonesia and the Philippines have been in the process, and some more countries have expressed interest in a future application.

As ASEAN is a disaster-prone region and every country has a risk of becoming a disaster-affected country, some AMS have been strengthening EMTCC management capacity for receiving international assistance. This progress is evident, particularly in Thailand, Viet Nam, the Philippines, and Indonesia, all of which are former RCD host countries.

It is also important to note that Cambodia and Lao PDR, formerly considered less disaster-prone countries and with different areas of interest, have begun giving importance to DHM in terms of curricula development, the establishment of EMTCC structure, as well as an interest in developing EMT in accordance with the WHO minimum requirements in future.

Products of the ARCH Project such as forms of MRED or HNA have been applied by a few AMS into their domestic disaster management framework and utilized in actual disaster responses. Furthermore, not only the substantial products but also their development process, in which all AMS were highly involved, have impacted AMS significantly as part of knowledge sharing.

A regional network established through the ARCH Project is beginning to function, with Lao PDR referring to the Thailand model for their N-EMT training curriculum design.

A peer-review activity is planned in the forthcoming ARCH Project Phase 2 to follow up the progress of each AMS made in achieving national targets set out in the POA/ALD on DHM; thus, this established regional network with trust will be an important foundation for mutual support among AMS, and towards sustainable development of DHM in ASEAN.

The ARCH Project is highly appreciated by AMS as an opportunity to share knowledge and experience among countries, thereby contributing to achieving the “One ASEAN, One Response” concept, as well as the driving force for each AMS to develop its capacity in DHM.

II. Impact of the ARCH Project on Japan

A. Introduction

Japan is a country with many disasters. Natural disasters such as typhoons, heavy rains, heavy snowfalls, floods, tornadoes, volcanic eruptions, and earthquakes are experienced almost every year. In addition, Japan has experienced many disasters other than natural disasters such as the Japan Airlines crash in 1985, 1995 the Sarin Gas Attack on the Tokyo Subway, and the nuclear accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant during the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011. Japan’s disaster medical system has improved significantly over the past 30 years by gaining experience of such a wide variety of disasters that is unprecedented in the world. Japan is implementing one of the world’s leading disaster medical systems. The ARCH Project exports all those Japanese experiences and knowledge to neighboring ASEAN countries which often experience natural disasters and help develop their own capacity to sustain from disasters. In recent years, ASEAN countries have shown rapid economic growth, and the disaster medical system is also developing rapidly. This development of ASEAN has also become another eye-opener for Japan. This review provides an overview of the impact of the ARCH Project on Japan.

B. History of Disaster Medicine in Japan (from International to Domestic)

In Japan, there is a saying, “Fools learn from experience, wise people learn from history,” and it is essential to take history into account in order to understand the position of the ARCH Project. Therefore, it is started with the history of disaster medicine in Japan.

Disaster medicine in Japan began with the Cambodian refugees’ relief mission in 1979. The response of medical teams to Cambodian refugees is the first response of the Japanese medical team, both domestically and internationally. This was a significant achievement and is said to be the origin of disaster medicine in Japan. For this medical response to Cambodian refugees, the medical team had delay in response because the dispatching system was not established at that time, and no systematic operations were conducted since the team members consisted of only medical personnel without logisticians at that moment. The Japan Medical Team for Disaster Relief (JMTDR) was established in 1982 based on this Cambodian experience. As a result, a system was established to register medical personnel as volunteers in peacetime, and to dispatch a team to respond quickly to disasters overseas. Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) took a secretarial role of JMTDR. After accumulating responses such as dispatching to Ethiopia, the Act on Dispatch of the Japan Disaster Relief Team (JDR Law) was enforced in 1987 for legal support.6 After the JDR Law was enforced, the JDR team responded 59 times by 2020.7

With international disaster response development, the academic field was also developed internationally. Although there was no domestic academic society on disasters in Japan at that time, the first international academic society called Asia Pacific Conference on Disaster Medicine (APCDM) was established in 1988 by Dr. Muneo Ota and Dr. Yasuhiro Yamamoto who is the founder of JMTDR. Dr. S. William A. Gunn of the World Health Organization and the heavyweights of ASEAN countries, Dr. H. Abdul Radjak, and Dr. Wayne Greene from Canada cooperated in the creation of APCDM. It is worth noting that at this point, an attempt was made to strengthen cooperation in the Asia-Pacific region.

During the course of the advancement of international disaster medicine, the lack of domestic disaster medical system was revealed in 1995 when the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake (GHAE) happened. Of the 6,434 deaths, 500 were reported as preventable disaster deaths.Reference Ukai8,Reference Yamanouchi, Sasaki and Tsuruwa9 One of the main reasons for the delay in preparing for domestic disaster medical system was that major disasters did not hit Japan after the 1959 Isewan Typhoon (Typhoon Vera) until the 1995 GHAE. After GHAE, disaster medicine and disaster medical system in Japan made rapid progress.Reference Kondo, Koido and Morino10 The Japan Disaster Medicine Study Group was established in 1996 and is now the Japanese Association for Disaster Medicine (JADM). The rapid progress of domestic disaster medicine was possible because Japan had rich experience in international disaster response. For example, the people who created the JDR medical team founded Japan Disaster Medical Assistant Team (DMAT); Japan DMAT training is based on JDR medical team member training.Reference Kondo, Koido and Morino10 The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan has jurisdiction over JDR and the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare has jurisdiction over Japan DMAT. Although both JDR and Japan DMAT are under the jurisdictions of different Ministries, the fact that the membership of both teams is the same reduces the negative effects of the vertically divided administration and enables Japan for quick decision making at the time of disaster response.

C. Current Japanese Disaster Medical System (Domestic to Overseas)

Japan DMAT, Disaster Base Hospitals, Emergency Medical Information System (EMIS), etc. are now world-class disaster medical systems. Japan DMAT currently has approximately 1,700 teams and over 15,000 members nation-wide. Seven hundred forty-three Disaster Base Hospitals have been designated and maintained. EMIS has been implemented in all 8,000 hospitals throughout the nation. According to the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disaster’s Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT), 80% of the world’s natural disasters occur in Asia. If Japan can transfer knowledge that has been accumulated to Asia, it will eventually provide relief to the affected people. Japan inevitably has the responsibility to give knowledge back to Asia because Japanese disaster medicine developed well through all those international responses. From 2013 to 2015, the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan conducted research on “Study on technology transfer of earthquake disaster response and reconstruction scheme in Japan’s health care system” to export Japan’s disaster response knowledge to other countries.11 This became one of the foundations of the ARCH Project. Since then, Japan has been trying to transfer knowledge of disaster medicine to ASEAN countries. While the ARCH Project had started as knowledge and technique transfer of disaster medical response from Japan, Japan started to face a lot of opportunities to learn from other countries.

D. From Overseas to Domestic Again Positive Spiral Effects

Japan’s disaster medicine has consistently learned from the international response and maintains an attitude of sharing knowledge that has been earned from the international response to other countries. Japan learned the practicality of Surveillance in Post-Extreme Emergencies and Disasters (SPEED) in the Philippines through the dispatch of JDR to the super typhoon Yolanda that hit the Philippines in 2013, and developed the Japanese version of SPEED (J-SPEED). J-SPEED has transformed Japan’s disaster medicine into a form that can be adjusted based on data. Japan proposed J-SPEED to WHO for the international sharing of this knowledge. Based on the proposal, WHO established a Working Group to develop the EMT Minimum Data Set (MDS) and adopted it as the WHO International Standard. Reference Kubo, Salio, Koido, Chan and Shaw12

The academic spiral effect has also begun. The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 and WHO Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management (H-EDRM) Framework are recommending promoting and enhancing the training capacities in the field of disaster medicine and supporting and training community health groups in disaster risk reduction approaches in health programs, in collaboration with other sectors, at national level and implementation of regional cooperation mechanism.13,14 The ARCH Project is exactly the ASEAN platform. ARCH’s SOP has developed from learnings from WHO’s SOP. Now ARCH’s SOP is becoming the foundation for creating SOPs for accepting medical teams from overseas in the event of a catastrophic disaster in Japan.

E. Summary of Impact of the ARCH Project on Japan

The primary purpose of the ARCH Project was to improve the disaster response capabilities of AMS and strengthen cooperation between AMS together with Japan and some other countries. Disasters are occurring frequently and intensifying every year globally; therefore, a one-way vector of transferring disaster medicine knowledge overseas is not suitable. It is important to build a bi-directional relationship between ASEAN and Japan to manage future expected disasters. Japan is anticipating the Nankai Trough earthquake in near future and is expecting to be overwhelmingly short of medical resources. At the time of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake (GEJE), Japan officially accepted medical support from the Israel Medical Support Team, Jordan Medical Support Team, Thai Medical Support Team, and Philippine Medical Support Team and has a track record of entering Japan as a medical team to help the people. But SOPs are yet to be established for accepting medical teams from overseas.

Considerations of providing medical assistance to disaster-affected countries and receiving international medical assistance as a set will lead to the improvement of international disaster medicine. In that sense, the mission of ARCH is actually a mission for Japan. It was reconfirmed that it is important to exchange information quickly across countries in recent coronavirus disasters. A personal face-to-face network can be a great force in an emergency. Globalization is also essential for young Japanese human resources, and ARCH is the best field.

III. Conclusion

ARCH Project is highly appreciated by AMS as the opportunity to share knowledge and experience among countries and thereby contributing to achieving the “One ASEAN, One Response” concept, as well as the driving force for each AMS to develop its capacity in DHM. While the ARCH Project started to support AMS to strengthen its regional capacity in disaster health management, it is important to build a bi-directional relationship between ASEAN and Japan in terms of mutual learning and support to tackle future disasters.

Conflicts of interest/financial support

The ARCH Project was funded by JICA as part of the Official Development Assistance of the Government of Japan in collaboration with NIEM/MOPH Thailand as counterpart agencies. This publication was completely funded by JICA as a part of the ARCH Project. Shuichi Ikeda and Taro Kita are members of the expert team deputed by JICA. All other authors do not have any conflict of interest to declare.

Author Contribution

This manuscript was conceptualized and contributed by the following authors: Taro Kita and Shuichi Ikeda (Impact on AMS), Yuichi Koido, and Yoshiki Toyokuni (Impact on Japan). All authors have read through the final manuscript and agreed to publication.