INTRODUCTION

Sociolinguistic research has increasingly emphasised the role of ‘personae’ in explaining the relationship between local-level interactional practices and large-scale patterns of language variation and change (Eckert Reference Eckert2008; D'Onofrio Reference D'Onofrio2020). Personae—or figures of personhood—can be defined as those semiotic registers or ‘indexicals’ that are ideologically linked with some recognizable person type (Agha Reference Agha2003, Reference Agha2007; Park Reference Park2021). Though personae need not be named entities, they are often reified as stable identity categories and assigned some label, such as ‘hútòng chuànzi’ (Zhang Reference Zhang2005), ‘the Hun’ (Ilbury Reference Ilbury2022), and the ‘Valley Girl’ (Pratt & D'Onofrio Reference Pratt and D'Onofrio2017). These figures are ‘chronotopic’ in that they are linked to the specific spatial and temporal contexts in which they emerge (Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin1981; Park Reference Park2021). Subsequently, personae can be defined as ideological figures that mediate macro-social group patterns and that are shaped by prevalent metapragmatic discourses of social difference (Coupland Reference Coupland2001; Eckert Reference Eckert2008; D'Onofrio Reference D'Onofrio2020).

In this article, I add to this body of work by exploring a figure of personhood that is linked to Multicultural London English (MLE; Cheshire, Kerswill, Fox, & Torgersen Reference Cheshire, Kerswill;, Fox; and Torgersen2008, Reference Cheshire, Kerswill;, Fox; and Torgersen2011). Through an analysis of parodic videos tagged #roadman extracted from the social media platform TikTok, I demonstrate that a subset of MLE features have become enregistered with a particular type of personae—or characterological figure (Agha Reference Agha2007)—that is imbued with racialized stereotypes: the ‘roadman’. These parodies, I argue, circulate anti-Black and anti-poor representations of the imagined user that have the potential to become internalised as characteristics of MLE speakers more generally.

Beyond an analysis of its characterological indices, I demonstrate that the roadman persona signals the ‘recontextualization’ (Bauman & Briggs Reference Bauman and Briggs1990) of MLE, from a variety spoken by working-class youth living in inner-city neighbourhoods in London, to a UK-wide style that is associated with subcultural orientation: a Black British interpretation of Northern American ‘street’ culture often referred to as ‘road’ culture (Gunter Reference Gunter2008; Reid Reference Reid2017; Bakkali Reference Bakkali2018). The mediatisation and circulation of the roadman, I argue, signals a type of ‘raciolinguistic enregisterment’ whereby ‘signs of race and language are naturalized as discrete, recognizable sets’ (Rosa & Flores Reference Rosa and Flores2017:631; see also Smalls Reference Smalls2015).

Concluding, I consider the role of social media in contemporary processes of enregisterment arguing that, through the participatory design and translocal networking affordances of social media platforms, users play an active role in the linkage of social meanings and person-types by (re)circulating and (re)producing ideologies of difference—both old and new—of speech styles and their related social figures which are consumed by users beyond the fixed time-space boundaries of the offline ‘speech community’. These developments, I argue, not only shed light on the social dynamics of language, race, and ethnicity in the UK today but also have significant consequences for ‘sociolinguistic change’ (Androutsopoulos Reference Androutsopoulos2014) more generally.

STYLISATION

As discussed above, a figure of personhood—or a ‘characterological figure’ (Agha Reference Agha2007)—is a ‘set of indexicals that are linked with a performable person type’ (Park Reference Park2021:47). These figures are perhaps most identifiable when they are intertextually and figuratively referenced by users who momentarily stylise the voice of the persona. Stylisation here refers to those contexts in which individuals are seen to temporarily adopt styles that different from the users’ habitual style, and/or different from those typically perceived to be conventional for the speaking context (Rampton Reference Rampton1995; Coupland Reference Coupland2001, Reference Coupland2007).

Current theories of stylisation draw heavily on Bakhtin's argument that language is ‘heteroglossic’ or imbued with others’ words and voices. For Bakhtin, stylisation refers to the contexts in which speakers produce ‘an artistic image of another's language’ (1981:361). This double-voicing may be to align with the voice (and identity) stylised—unidirectional—or to subvert or mock the inferred voice (and identity)—varidirectional.

Though we may be tempted to view stylisation as a form of ‘language play’, research has demonstrated that these interactions are informed by ideologies of the social identities and voices that speakers stylise. A case in point is Rampton's (Reference Rampton1995) now seminal work on ‘crossing’ in which he observes that multiethnic youth stylise elements of non-habitual styles such as English-based Creole, Punjabi, and Asian English as a way of managing social and interactional relations. According to Rampton, the selection of a variety is linked to the ideological associations of that style and its interactional potentials. For instance, he argues that some speakers stylised aspects of Creole to deploy an assertive stance that was ideologically associated with their Creole-speaking peers. Stylised Asian English, on the other hand, was used to publicly ridicule Othered students by performing an incompetent yet obsequious immigrant persona developed during British colonial rule in India. Thus, as Rampton's analysis illustrates, stylised interactions are informed by and (re)produce social relations.

Staged performances

Though most research has focussed on stylisation in everyday interaction (see inter alia Rampton Reference Rampton1995; Coupland Reference Coupland2001; Snell Reference Snell2010; Jaspers Reference Jaspers2011), a growing body of work explores stylisation in media and so-called ‘staged’ performances. ‘Staged performances’ refer to those contexts in which there is an ‘overt, scheduled identification and elevation (usually literally) of one or more people to perform, typically on a stage, or in a stage-like area such as the space in front of a camera or microphone’ (Bell & Gibson Reference Bell and Gibson2011:557). This includes the literal stages in dedicated venues such as theatres and cinemas and also the figurative ‘stages’ of social and digital media. Staged performances are arguably rich contexts for analyses of stylisation given that media act as important socializing agents in shaping individuals’ perceptions of people and their language(s). As ‘authorities’ (Gal Reference Gal2019), media contribute to the (re)production of cultural norms and ideologies of speakers and their speech styles by representing and circulating metapragmatic discourses (Agha Reference Agha2007; Mortensen, Coupland, & Thogersen Reference Mortensen, Coupland and Thogersen2017; Ilbury Reference Ilbury2022).

A case in point is found in Bucholtz & Lopez’ (Reference Bucholtz and Lopez2011) analysis of ‘linguistic minstrelsy’ in Hollywood films. In that analysis, the authors argue that the use of African American English by European American actors functions as a form of language-based blackface minstrelsy. They argue further that these mock language practices reproduce entrenched ideologies of language, race, and gender that ultimately reinforce the problematic dichotomy between ‘rational middle-class whiteness and physical working-class blackness’ (Reference Bucholtz and Lopez2011:702).

Similar issues are explored in Slobe's (Reference Slobe2018) analysis of digitally mediated ‘Mock White Girl’ (MWG) performances. In MWG videos, users are seen to parody an imagined linguistic and semiotic style associated with middle-class White American females. These performances, Slobe argues, reveal ‘the dynamic, changing, and evolving position of middle-class white girls in modern United States ideology and society’ (Reference Slobe2018:562). Thus, MWG performances ultimately (re)produce racialized ideologies of those it mocks, that is, middle-class White women.

RECONTEXTUALISATION AND ENREGISTERMENT

Although high performances often reinforce existing sociolinguistic hierarchies, they can also be sites in which sociolinguistic meaning is critiqued and reinterpreted. This is perhaps most obvious in the ‘participatory contexts’ of social media. For instance, in a study of German dialects in amateur videos on YouTube, Androutsopoulos (Reference Androutsopoulos, Tannen and Trester2013:66) argues that such videos ‘destabilize existing mass-mediated regimes of dialect representation by pluralizing the performance and stylisation of the dialects’. He further proposes that stylised performances of the Berlin dialect could reconfigure indexical links by critiquing the stereotype of the male working-class speaker and instead spotlighting ‘new exemplary’ speakers of the dialect. Thus, for Androutsopoulos (Reference Androutsopoulos2014:32), the participatory nature of social and digital media make these important contexts for sociolinguistic change, since they make ‘metapragmatic typifications of registers available to large audiences for recontextualizations and response’.

‘Recontextualisation’ here describes the sociolinguistic process in which signs (however broadly defined) are decontextualised from their original source and appear in different contexts of use (Bauman & Briggs Reference Bauman and Briggs1990). This is the case, for instance, when working-class varieties become mainstreamed and appropriated in popular culture. This is evident in the recontextualisation of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) as a ‘global youth style’—a development which can be traced back to the status of hip hop as a form of political and creative resistance amongst marginalised youth (Alim Reference Alim, Bloomquist, Green and Lanehart2015). For instance, in Cutler & Røyneland's (Reference Cutler, Røyneland, Nortier and Svensen2015) work on hip hop in the US and Norway, they demonstrate that youth from immigrant backgrounds use features of AAVE—or Hip Hop Nation Language (HHNL; Alim Reference Alim, Bloomquist, Green and Lanehart2015)—to index their alignment with a ‘supranational community of practice’. The authors argue that marginalised youth adopt these practices as a means of empowering themselves by challenging hegemonic ideologies of national belonging and resisting assimilation (Reference Alim, Bloomquist, Green and Lanehart2015:162–63; see also Chun Reference Chun2001).

For signs to become recontextualised they must undergo a process of (re)enregisterment. Agha defines enregisterment as the process in which ‘performable signs become recognized (and regrouped) as belonging to distinct, differentially valorized semiotic registers by a population’ (Reference Agha2007:81). We can think of (re)contextualisation as a transformation at the level of the sign (or indexical field), whilst (re)enregisterment refers to the emergence of an indexical differentiator—or personae—that is specified in space and time and which can be enacted and embodied in discourse (Busch & Spitzmüller Reference Busch and Spitzmüller2021).

An illustration of this process is found in Ilbury (Reference Ilbury2019) where I argue that a subset of AAVE features have become appropriated and recontextualised as a ‘gay style’. This style, I argue, is linked to a figure of personhood that is imbued with essentialised imaginings of the ‘typical’ Black woman. The recontextualization of AAVE features then, from ‘a variety used by Black working-class Americans’, to components of a ‘gay style’ associated with a particular figure of personhood (‘the Sassy Queen’), infers that these features have become (re)enregistered.

As these examples demonstrate, recontextualisation is not an ideologically neutral process. Rather, recontextualisation and relatedly, contextualisation, are informed by ‘the political economy of texts’ (Bauman & Briggs Reference Bauman and Briggs1990:76). That is to say that recontextualization is a culturally constructed and socially situated process that is shaped by ideology, power differentials, and social and cultural norms. An analysis of the mechanisms through which registers become (re)contextualised therefore can help us identify not only how prevalent stereotypes and metapragmatic discourses are (re)circulated, but also the social conditions that lead to the emergence of those discourses in the first place (Agha Reference Agha2007; Park Reference Park2021). The present article examines these issues with regard to the multiethnolect—MLE.

MULTICULTURAL LONDON ENGLISH

Over the past fifteen or so years, sociolinguistic research has documented the emergence and subsequent spread of a new variety of English—what has been termed ‘Multicultural London English’ (MLE; Cheshire et al. Reference Cheshire, Kerswill;, Fox; and Torgersen2008, Reference Cheshire, Kerswill;, Fox; and Torgersen2011). MLE is typically spoken by young working-class individuals living in inner-city neighbourhoods in London. For many speakers, MLE has become the unmarked Labovian working-class vernacular, largely supplanting traditional (i.e. White) varieties, such as Cockney (Fox Reference Fox2015). Often defined as a ‘multiethnolect’ (Clyne Reference Clyne2000),Footnote 1 individuals from a range of ethnic and linguistic backgrounds speak MLE, with its distribution apparently predicted by the ethnic diversity of the speakers’ social network (Cheshire et al. Reference Cheshire, Kerswill;, Fox; and Torgersen2008). However, whilst both Black and White individuals use the variety, MLE is often racialized to the extent that the variety and related speech styles are regularly perceived as ‘sounding Black’ (Drummond Reference Drummond2016). This raciolinguistic ideology is so pervasive that earlier (non-academic) labels used to describe MLE (e.g. ‘Jafaican’: lit. fake Jamaican) explicitly reference the association between Blackness and the variety.

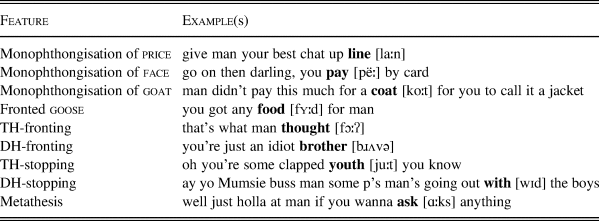

MLE is characterised by a number of innovative phonological, lexical, grammatical, and discourse-pragmatic features. Though a fuller discussion of its linguistic inventory is outside the scope of this article, some typical MLE features include the extreme fronting of goose to [ʏː], the (near) monophthongisation of price, the pronoun man, and various lexical innovations, such as peng ‘nice’, fam ‘family/friend’, and bare ‘lots of’ (Cheshire et al. Reference Cheshire, Kerswill;, Fox; and Torgersen2008, Reference Cheshire, Kerswill;, Fox; and Torgersen2011; Cheshire Reference Cheshire2013; Fox Reference Fox2015; Ilbury Reference Ilbury2021; Pichler Reference Pichler2021; see Table 1).

Table 1. Selected MLE features and examples.

More recent research has also identified parallels between MLE and varieties spoken in geographically disparate cities in the UK, such as Manchester and Birmingham. In his work on youth language in Manchester, Drummond (Reference Drummond2018) identifies a number of MLE-type features in the speech of the young people attending a non-mainstream school. For instance, the young people in Drummond's study used MLE lexis such as peng and peak, had MLE-type vowel inventories, and used MLE consonantal features such as TH- and DH- stopping. This leads Drummond to argue for a more general variety—what he calls ‘Multicultural (Urban) British English’ or M(U)BE (henceforth MBE).

Though most research on MLE/MBE has focussed on describing the broad social distribution of the variety, Drummond's (Reference Drummond2018) work emphasises the role of stylistic practice in the use of these features. In an analysis of TH-stopping (i.e. [t] for /θ/), Drummond argues that speakers utilise the stylistic potential of this feature to index their participation in grime—a Black British musical genre that emerged in East London in the early 2000s. Drummond's findings therefore seem to suggest that there has been a type of recontextualisation of MLE/MBE features from a variety spoken by young working-class individuals (in London) to a style used by speakers who wish to index their alignment with grime—akin to the development of AAVE and hip hop (Chun Reference Chun2001; Cutler & Røyneland Reference Cutler, Røyneland, Nortier and Svensen2015). However, aside from Drummond's (Reference Drummond2018) analysis, there are few stylistic perspectives on MLE/MBE (henceforth MLE) and less work has considered the role of personae in mediating these practices. Subsequently, this article explores these issues by analysing the circulation of a characterological figure—the roadman—which signals the recontextualisation of MLE.

METHODS

TikTok

This article examines data from the social media platform, TikTok. Launched in 2016, the video-sharing platform TikTok has quickly become one of the most popular social media apps amongst Generation Z (i.e. those born since 1997). In 2020, it was reported that 24% of fifteen to twenty-four year olds had an account, with young people spending up to seventy minutes on TikTok each day (Statista 2022a). In January 2022, the platform had just under nine million active monthly users in the UK (Statista 2022b).

TikTok content comprises user-generated short videos ranging from fifteen seconds to three minutes. Most content is created by a small pool of contributors—sometimes influencers—relative to users. Videos are typically recorded via the integrated camera found on most contemporary smartphones.

When a user accesses the app, they are presented with the For You Page (FYP)—a continuous stream of video content that is algorithmically tailored to their viewing interests based on past interactions and preferences. Videos can be found by using the search function or by viewing videos related to a specific hashtag. Users can interact with content by leaving a ‘comment’ or using the ‘like’ function. Given that videos are set to public by default, content can be shared beyond the platform. TikTok also integrates the ‘lip sync’ functionality of its precursor, Musical.ly, allowing users to remix original soundtracks in videos.

TikTok data

This article combines computational and ethnographic methods to explore parodic performance videos that are tagged #roadman. The current project is contextualised with reference to a broader blended offline/online ethnography in an East London youth group and my own positionality as a Londoner (see Ilbury Reference Ilbury2021). The term roadman featured regularly in the conversations of the young people at the youth group, and it was widespread during my own schooling in London some twenty years ago. Thus, whilst I focus solely on TikTok here, the analysis is informed by my more extensive ethnographic work and experience of living in (East) London. Subsequently, it is important to establish that this identity did not originate in social media. As discussed above, the term roadman appears to be well established as an identity category and other ethnographic research describes individuals who actively align with this identity label and participate in this lifestyle (Reid Reference Reid2017; Bakkali Reference Bakkali2018).

The label roadman can be defined as a Black British cultural descriptor that is rooted in the Caribbean diaspora. In literal terms, the term refers to a ‘man who does Road’ (Boakye Reference Boakye2019:316). ‘Road’ here does not simply refer to a ‘vehicle highway’, but rather the everyday realities of urban life (Reid Reference Reid2017; Bakkali Reference Bakkali2018). The broader cultural alignment—road culture—is heavily influenced by Black Atlantic diasporic popular cultures (Gunter Reference Gunter2008:325). This is evident in the etymology of the term roadman which originates from Jamaican English (JE) following a common practice in JE to add the suffix -man to the profession/role of the individual, hence wasteman (‘a man who is a waste of space’) and battyman (‘a homosexual man’). However, whilst this identity is rooted in Black British diasporic cultures, defining road culture in racial terms should be approached with caution since, in reality, participation crosscuts ethnicity and race (Gunter Reference Gunter2008; Bakkali Reference Bakkali2018).

Unlike other working-class labels and stereotypes which are almost always pejorative (e.g. chav; Bennett Reference Bennett2012), the term roadman can be either negative or positive depending on the context in which it is used. As Boakye (Reference Boakye2019:319) observes, for some young men the term has become a ‘perversely aspirational stereotype that offers status from the margins’. Today, the descriptor is widespread in popular discourse, most likely owing to the recent mainstream popularity of grime music where references to the term and identity are common.

Given that this identity did not emerge in digital contexts, I do not intend to describe the historical development of this persona. Rather, I focus on digital contexts here to uncover the prevalent metapragmatic discourses that inform amateur parody videos (see also Androutsopoulos Reference Androutsopoulos, Tannen and Trester2013). In other words, I use social media data to explore the stylistic (linguistic and otherwise) components that are recruited in parodic performances of the roadman to better understand the relevance of this figure in the broader (re)contextualisation of MLE.

The current article utilises insights from a two-year period of digital ethnographic research on TikTok (see Pink, Horst, Postill, Hjorth, Lewis, & Tacchi Reference Pink, Horst, Postill, Hjorth, Lewis and Tacchi2015). Over the span of this period, I became an active participant researcher on the app. I made digital field notes and extracted videos that contained tags and discussions relevant to ‘youth language in London’. I also followed accounts that used relevant hashtags (e.g. #London, #MLE) and engaged with related discussion threads in other forums.

To extract the data analysed in this article, I automatically scraped 500 TikTok videos at random that contained the hashtag #roadman. Using the Python wrapper TikTokApi (Teather Reference Teather2022), I downloaded both the video and its metadata. All videos analysed were set to ‘public’ by default and could be viewed on the platform without the user registering for an account. At the time of extracting the posts (March 2022), all posts were uploaded within the past three years. For the purposes of the present article, my focus is principally on the content of posts, as opposed to how those posts were received or interacted with.

After collecting the data, videos that were tangential or otherwise unrelated to #roadman were removed given that it is common practice for users to add unrelated but popular hashtags to increase post visibility. I likewise removed any video that was not intended to be a parodic performance. The remaining videos were manually transcribed since automated transcription software proved to be highly inaccurate on this data. The final corpus comprises 373 videos totalling 23,711 words. In what follows, I provide an analysis of #roadman videos, focussing first on their stylistic characteristics, before turning to their linguistic content.

STYLISING THE ROADMAN

Stylisation strategies

Videos tagged #roadman—in Shifman's (Reference Shifman2013) terms—constitute a ‘meme genre’. That is to say that #roadman parodies recursively employ a set of shared stylistic elements regardless of the creator of the video. In all videos (and likely in all parodies of this type), the roadman is depicted as male. Although some TikTok users who do not identify/present as male stylise the roadman, the character is intended to be read as male. This is marked explicitly in the label (literally a man that does ‘road’) and in the content of the videos (such as the fictional name of the character, e.g. ‘Marcel’). Note, there are no corresponding terms for the female equivalent of this identity (i.e. roadwoman; see Reid Reference Reid2017; Bakkali Reference Bakkali2018; Boakye Reference Boakye2019). Whilst the race of the actor is variable with both Black and White creators stylising the roadman, as noted previously, the label ‘roadman’ and road culture are racialized insofar that they are rooted in a Black British consciousness. Thus, though the characters’ race or ethnicity is not explicitly referenced, roadman performances indirectly evoke racialized meanings through the genealogy of the cultural orientation that they anchored in and, as I go on to demonstrate, linguistic features that (indirectly) index Blackness.

Characterologically, the roadman is hypermasculine (see Gunter Reference Gunter2008) and markedly heterosexual. His sexual tastes and desires are often overtly referenced. For instance, in several videos the roadman is seen to compliment his female interlocutor on her physical appearance, such as her bunda ‘buttocks’ whilst in others, he asserts his sexual prowess (e.g. ‘let's just say man's knocked a few balls in your mum's backyard before’). These tropes co-occur with other hypermasculine styles of self-presentation, including references to his violent lifestyle and criminal orientation. Indeed, in the vast majority of #roadman parody videos, the character is depicted as involved in some criminal activity. Consider extract (1) from an imagined interaction between the roadman and an American tourist. In the scene, the roadman attempts to steal the tourist's phone. When he refuses to surrender his phone, the roadman threatens to ‘shank’ (stab) the tourist.

(1)

As in the above, themes of violence and criminality in #roadman parodies appear to recursively reference the character's ‘outlaw status’ (Boakye Reference Boakye2019:318) and his ‘road’ orientation, that is, the lived experiences and realities of everyday urban life. At the same time, they also evoke colonial logics that equate Blackness with hypermasculinity, violence, and criminality which, in turn, play into anti-Black and anti-poor narratives (see also Bucholtz & Lopez Reference Bucholtz and Lopez2011; Chun Reference Chun2013; Smalls Reference Smalls2015).

Nevertheless, these performances are not intended to be taken at face value. Indeed, the overwhelming bulk of #roadman performances are parody videos. Of the original 500 videos that were extracted, 373 are parodies of the roadman identity. The comedic value of the videos can be judged both by the content (e.g. nonsensical scenes) and hashtags which explicitly reference this intention, for example, #comedy (N = 322), #skit (N = 153), and #sketch (N = 13).

The stylisation is achieved through tropes and theatrical features that essentially ‘frame’ (Goffman Reference Goffman1974) the performance as a parody or, in Bakhtin's (Reference Bakhtin1981) terms, a type of ‘varidirectional double-voicing’. This is generally achieved in one of two ways. The first performative strategy is what I call ‘linguistic stylisation’, where the character is performed through one semiotic channel—language. Often, in these videos, the user is seen to initially adopt a speech style and identity (which also may be stylised) that is in sharp contrast to that of the roadman, thus creating a paradox between the two opposing styles and identities. For instance, extract (2) is from a video in which the roadman expresses his desire to become romantically engaged with his female interlocutor. In the video, the user initially uses a stylised high-pitch, hyper-feminine, Americanised style (underlined), before dramatically shifting into a low-pitch, hypermasculine, MLE-type style. The dialogue contains numerous MLE features including lexical features link up ‘get together’ and ahlie ‘agreement’, the tag question innit, monophthongal face, and discourse-pragmatic (DP) marker styll. Footnote 2

(2) It's officially Christmas Eve and you know what that means (.) we can link up under the mistletoe innit? (.) like all I want for Christmas is you fam you a peng ting ahlie? (.) like I'm on the nice list babes I swear styll

ɪts əfɪʃəli krɪsməs iv ən jʊ noʊ wʌt ðət miːnz (.) wi kən lɪŋk ʌp ʌndə ðə mɪsltəʊ ɪnɪʔ ↗ (.) laɪːk ɔː aɪ wɒnt fə krɪsməs ɪz jʊ fæm jʊ ə pɛŋ tɪn alaɪː ↗ (.) laː aɪm ɒn ðə naːs lɪst beɪbz aɪ sweə stɔːwː

The stylisation here draws on the indexical dichotomies of nationality (American vs. British), gender identity/expression (female/femininity vs. male/masculinity), and style (American English vs. MLE) to both ‘frame’ the performance as a stylised display and to evoke the roadman persona. By stylising two contrasting speech styles and identities, the user strategically exploits their social meanings to perform the roadman style as British, MLE, and hypermasculine.

Other performances are likewise ‘framed’ as stylisation, but unlike those previously discussed that achieve this solely through language, the second type of video utilises cinematographic features such as voice modifiers, (unusual) props (e.g. a towel for hair), green-screen backgrounds, and other theatrical elements to ‘frame’ the performance. I refer to this type of performance as ‘theatrical stylisations’. Common to this category of video is that the roadman appears in hypothetical comedic situations, such as when he ‘goes to parents evening’ or ‘becomes a bus driver’. Examples are Figures 1 and 2, where the roadman is recorded in two comedic vignettes: first, whilst he is at the beach on holiday, and second, whilst babysitting.

Figure 1. ‘If a roadman was at the beach on holiday’.

Figure 2. ‘The roadman babysitter’.

In these examples, the roadman is performed through an assemblage of semiotic resources. First, he is depicted in ‘streetwear’ attire (e.g. tracksuit, padded jacket), wearing fashionable athletic designer brands such as Nike, Adidas, and Reebok (see also Gunter Reference Gunter2008). This aesthetic appears to be maintained regardless of the weather conditions of the scene, such as in Figure 1 where the roadman is depicted relaxing on a beach on a summer's day dressed in clothing typically suited to the winter (e.g. jumper, puffer jacket, sweatpants, face mask).

As recursive elements of #roadman videos, these tastes, dispositions, and social habits become categorically linked with the roadman. This is most apparent with reference to his musical tastes, in particular his engagement with grime music. In Figure 1, the character is depicted relaxing to ‘I dunno’ by grime artists Tion Wayne, Dutchavelli, and Stormzy, whilst in Figure 2, the character dances (or flexes) to ‘Baby shark’ as if it were a grime track. Indeed, the characters’ engagement with the so-called ‘urban’ music scene (e.g. grime, drill) is a recurrent theme throughout, referencing the shared genealogy of the two cultures (see Boakye Reference Boakye2019).

Alongside the theatrical elements that typify these videos, we also see that the roadman is performed through an MLE-type style. For instance, consider extract (3)—a transcript of the first twenty seconds of the video in Figure 2.

(3)

As in extract (2), we see how the roadman persona is stylised through multiple MLE features such as the extreme fronting of goose in do, monophthongal price in fine, DH-stopping in that, lexical features such as flex, and the DP feature, styll.

Nevertheless, whilst ‘linguistic’ and ‘theatrical’ stylisations differ to some degree, they are comparable in the sense that, in both, the performer utilises a ‘strategically inauthentic’ style (Coupland Reference Coupland2007). That is to say that character that is being performed is not intended to be taken at face value but rather is intentionally ‘hyper-stylised’ for comedic effect. This is achieved through various means, such as comedic sketch routines that imagine the roadman in apparently incongruent situations and roles (e.g. ‘if a roadman dad went to parents evening’), humorous themes, and exaggerated pronunciations of MLE features (e.g. styll [stɔːwː]). Many of these features are not unique to this genre but are hallmarks of high performances (Bell & Gibson Reference Bell and Gibson2011). In the remainder of the analysis, I focus on the linguistic features of #roadman TikTok videos.

The roadman linguistic style

As discussed above, common to #roadman performances is the use of MLE-type style (Cheshire et al. Reference Cheshire, Kerswill;, Fox; and Torgersen2008, Reference Cheshire, Kerswill;, Fox; and Torgersen2011; Cheshire Reference Cheshire2013; Drummond Reference Drummond2018; Pichler Reference Pichler2021). These features are intentionally and overtly stylised by the video creators who are rarely MLE speakers themselves. Subsequently, and as in other stylised routines, users are not attempting to authentically replicate the target variety but are selectively and intentionally targeting a subset of MLE features that are indexically and ideologically associated with a particular social identity and style—in this case, the roadman.

Phonology

In videos where the MLE accent is stylised, roadman parodies reference the full MLE vocalic system, including the (near-)monophthongisation of the price, face, and goat diphthongs, and the extreme fronting of goose (see Table 2). These pronunciations are hyper-stylised but are extremely variable.

Table 2. Phonological features in #roadman TikTok videos.

Roadman parodies also reference several MLE consonantal features. This includes TH-stopping, referring to the substitution of the voiceless interdental fricative /θ/ with [t] (Cheshire et al. Reference Cheshire, Kerswill;, Fox; and Torgersen2008; Drummond Reference Drummond2018). As in the interactions of MLE speakers, this feature is largely restricted to two words: youth [juːt] and thing [tɪŋ]. However, unlike in speech where this feature is variable, in #roadman parodies, these words are categorically stopped, with all 110 tokens of /θ/ in thing and youth realised as [t]. This signifies what Bell & Gibson (Reference Bell and Gibson2011:568) refer to as ‘overshoot’—that features in stylised performances tend to be categorically produced for rhetorical or comedic effect.

Other common features include the retention of /h/, DH-stopping (i.e. [d] for /ð/ as in that [dat]), TH-/DH-fronting (i.e. [f] or [v] for /θ/ as in think [fɪŋk] and brother [bɹʌvə]), and the metathesis of ask which is categorically stylised as [ɑːks]—a feature which, through its association with Black vernaculars, induces the racialisation of the roadman persona. Finally, several connected speech processes are categorically represented, for example, going to [gɒnə] and all right [aɪt]. Table 2 provides a summary of the main phonological features of #roadman videos.

Though most performances stylise the phonology in combination with other features of the variety, some use a more restricted MLE style. For instance, a subset of videos imagine the roadman in profession that is apparently incongruent with his assumed aspirations and habits, such as ‘if lecturers/policemen/teachers spoke like Roadmen’. In these videos, the character is seen to use a style that references only grammatical, lexical, and discourse-pragmatic features of MLE. For this reason, counts are not provided for phonological features.

Grammar

Beyond phonology, perhaps the most salient feature of the roadman style is the MLE pronoun man (Cheshire Reference Cheshire2013). Roadman parodies make extensive use of man, with 862 tokens in just 373 videos. Aside from its high frequency, and perhaps due to its relative saliency in discourse, there is some metalinguistic awareness of the association between man and the roadman. Extract (4) is taken from a video entitled ‘Roadman teaches UK slang in US school’ in which the character is comically depicted teaching a class on pronouns. The extract contains five instances of man, both as a first-person singular (“man is the teacher”) and second-person singular (“man is wearing a grey hoody”) pronoun. In the extract, the character claims that “in the English language there's only one pronoun: Man” before concluding that there is “one pronoun for everything”. Of course, this is not literally true. Whilst man is relatively frequent in MLE, it is variable and co-occurs with other pronouns and there are social and pragmatic factors that constrain man (Cheshire Reference Cheshire2013). Subsequently, man appears to be intentionally ‘overshot’ (Bell & Gibson Reference Bell and Gibson2011:568) in order to exploit the indexical connection between the high frequency of the pronoun and the performed identity.

(4)

However, though man is overrepresented in the data, other less salient and (possibly) more nuanced aspects of MLE grammar are not stylised. The MLE pattern of was/were variation (Cheshire & Fox Reference Cheshire and Fox2009) or the absence of the allomorphy of the indefinite article a/an (Fox Reference Fox2015), for instance, do not feature in the videos. In fact, the only other grammatical feature stylised in these videos is the non-standard negative contraction, ain't (N = 59) as in “you ain't getting on man's bus”, a feature which is common in other varieties of (London) English. Thus, as expected in stylised performances, these parodies seem to intentionally target and stylise a restricted set of grammatical features (mostly man) that have high indexical value as salient markers of this identity (see also Bucholtz & Lopez Reference Bucholtz and Lopez2011).

Lexis

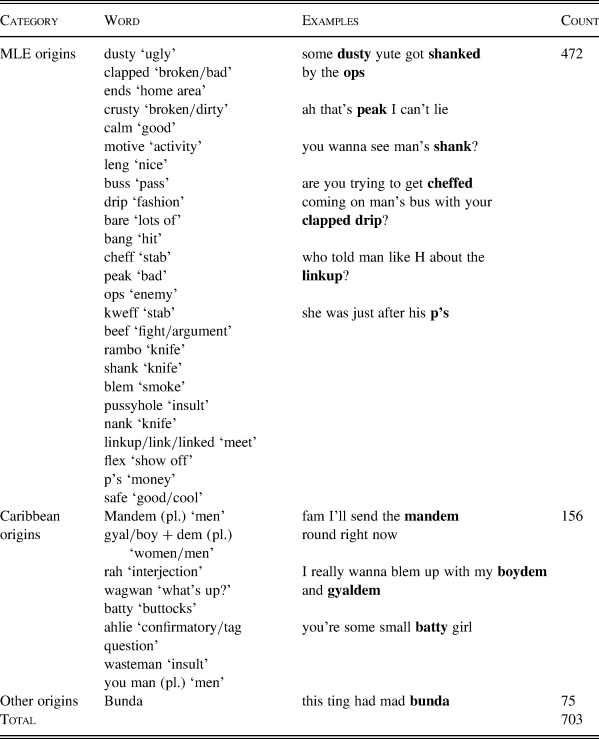

Roadman performances also reference various lexical features typical of MLE. This includes distinctively MLE words such as dusty ‘ugly’, cheff ‘stab or cut’, and leng ‘nice’, as well as terms borrowed from JE/Patwah including plural nouns mandem, you man ‘men’, and gyaldem ‘girls/women’. The use of JE/Patwah is perhaps unsurprising given that the lexicon of MLE is heavily influenced by Caribbean English varieties (Cheshire et al. Reference Cheshire, Kerswill;, Fox; and Torgersen2011). However, the high frequency of JE words also appears to reference racialisation of the roadman and MLE. Indeed, it is notable that words derived from other languages which form the ‘feature pool’ of MLE such as Arabic, for example wallahi ‘swear to God’ (cf. Oxbury Reference Oxbury2021), are not stylised. A summary of the lexical features is provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Lexical features in #roadman TikTok videos.Footnote 3

Most of the lexis references the violent and criminal activities that are ideologically associated with a racialized hypermasculinity that typifies the roadman. This includes words such as cheff ‘to stab or cut/ knife’ (N = 30), shank ‘a knife’ (N = 27), ops ‘opposites/rivals’ (N = 14), rambo ‘a knife’ (N = 3), nank ‘a knife’ (N = 3), and skeng ‘a knife’ (N = 3). This is made explicit in extract (5). In this video, the user linguistically stylises an imagined conversation between two characters in which the roadman proposes an additional set of words to be added to the ‘repertoire’. All of the words that the roadman character suggests—shank, cheff, kweff, rambo—refer to the same topic: knife crime.

(5)

This extract not only confirms the existence of a lexical repertoire that is enregistered as ‘roadman style’ but also it makes explicit an association between this identity and violence, in this case indexed through references to knife crime. In reality, however, research on road aligned youth has shown that, for the majority of individuals, life is not ‘spectacular’ or violent (Gunter Reference Gunter2008). Subsequently, these performances contribute to a type of raciolinguistic enregisterment (Rosa & Flores Reference Rosa and Flores2017) in which violence, criminality, and hyper-masculinity—qualities which are deemed to be key facets of the roadman identity—become social meanings indirectly linked to MLE.

Violence and aggression are also alluded to in the high frequency of swearwords and insults, including shit (N = 63), dickhead (N = 55), fuck (N = 45), and pussyhole (N = 23), which tend to occur in scenes where there is some (hypothetical) disagreement or confrontation. For instance, in extract (6), the user responds to a follower request to record a video that encourages them to clean their room.

(6) Clean your fucking room. It's a tip. It's disgusting. You need to sort it out fam ahlie, styll.

kleːn jə fʌkɪn ruːm ɪts ə tɪp ɪts dɪsgʌstɪn jʊ niːd tə sɔːt ɪt aʊt fæm alaɪː stɔːw

This linguistic stylisation draws on numerous aspects of MLE, including the lexis fam, ahlie, the DP marker styll, and MLE vocalic and consonantal features. These features co-occur with a dramatically marked monotonic pitch and the swearword fucking, which together evoke an aggressively confrontational stance. This stance is ideologically linked to the hypermasculinity that characterises the roadman and is strategically deployed to command the imagined addressee to clean their room.

Similar tropes are evoked in the use of the insult pussyhole (or <pussio>, lit. ‘vagina’) which has become an icon of the identity. In #roadman parodies, the /p/ in pussyhole is categorically hyper-aspirated, hence [phhhhhoːsioʊ]. This feature is so iconic that users show some metalinguistic awareness of association between hyper-aspirated /p/ and the roadman. For instance, Figure 3 is taken from a video in which different imagined characters (‘working mums’, ‘dads’, ‘roadman’) blow out a candle in a stereotypical manner. In the scene, the ‘roadman!’ enters the room and blows out the candle by uttering ‘pussyhole, fam’, in a very low-pitch accent and with a hyper-aspirated /p/. Similarly, in another video entitled ‘teaching ur mum slang’, an individual is recorded attempting to pronounce pussyhole by progressively creating a large build-up of air in the oral cavity before releasing a hyper-aspirated /p/. In this way, the phonetic emphasis on this particular lexical item implicitly indexes Blackness by evoking stances (‘aggression’, ‘violence’) that are associated with a racialized hypermasculinity (see also Chun Reference Chun2013).

Figure 3. ‘How do you blow out a candle? Ask the family too?’.

Discourse

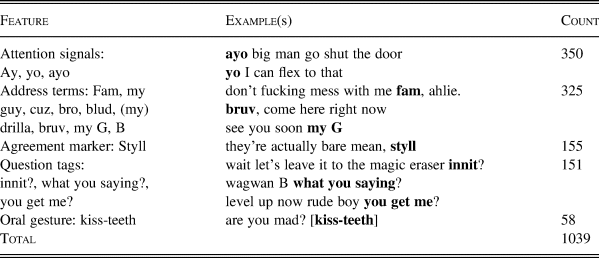

Roadman parody videos also reference a range of DP features typically found in MLE (see Table 4). This includes a range of different address terms that are generally used with male interlocutors including blud, bro, and my guy (Adams Reference Adams2018), the attention signals yo and ay (or <ey>; Ilbury Reference Ilbury2021), the agreement marker styll (Cheshire, Adams, & Hall Reference Cheshire, Adams; and Hall2022), the contraction ain't, and the tag innit (Pichler Reference Pichler2021).

Table 4. Discourse-pragmatic features in #roadman TikTok videos.

Similar to other features, the stylised DP features reflect a subset of those found in MLE and many are ‘overshot’ (Bell & Gibson Reference Bell and Gibson2011). For instance, styll, which is used by MLE speakers to acknowledge potential differences in the speaker's and interlocutor's beliefs and perspectives (Cheshire et al. Reference Cheshire, Adams; and Hall2022), is less specified in #roadman performances, used simply as a sentence final marker. Thus, the stylisations do not attempt to faithfully replicate MLE but rather exploit a subset of features for their socio-indexical meanings. This is perhaps most evident in the use of the attention signal ey (or <ay>). In research on this marker in MLE, I argue that ey/ay is used by speakers to perform a ‘dominant’ stance (Ilbury Reference Ilbury2021). The social meaning of this feature is apparent in roadman performances where the attention signal appears to be used in combination with other features to evoke a stance of dominance. For instance, consider extract (7).

(7) [kiss teeth] ay you man, watch out when we go out when we go out there cuh man got couple couple enemies and that [kiss teeth] you know what I'm saying. Nah, nah, nah ay [kiss teeth] [kiss teeth] ay don't talk back innit, cos like man'll cheff you fam like I'm friends with like Gordon Ramsay and he taught me a few knife skills innit.

In the extract, the attention signal transcribed as <ay> is combined with other features such as the MLE lexis cheff ‘stab’ and nank ‘knife’ and the verbal gesture ‘kiss teeth’ which is often used to signal disproval in Black (i.e. African and Caribbean) Englishes (Patrick & Figueroa Reference Patrick and Figueroa2002), along with themes of violence and criminality, to evoke a dominant or confrontational stance that is ideologically associated with the roadman persona. Of course, the play on the polysemy of cheff and references to the TV chef Gordon Ramsay suggest that this interaction—like all roadman parody videos—is not to be taken at face value. Nevertheless, we see that, yet again, #roadman parodies draw on the social meanings of a subset of MLE features to perform the roadman as ‘tough’, ‘aggressive’, and ‘violent’—tropes that are stereotypically and problematically associated with Black masculinity.

DISCUSSION

In the above, I have analysed the semiotic characteristics of parodic videos that target a specific type of persona—the roadman—that is linked with the multiethnolect, MLE. The roadman is, in Agha's (Reference Agha2003) terms, a ‘characterological figure’. In other words, it is a stereotyped image of personhood that can be performed in social discourse which, in the present analysis, is analysed in the embodied stylisation and ‘varidirectional voicing’ (Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin1981) that typify #roadman parodies on TikTok.

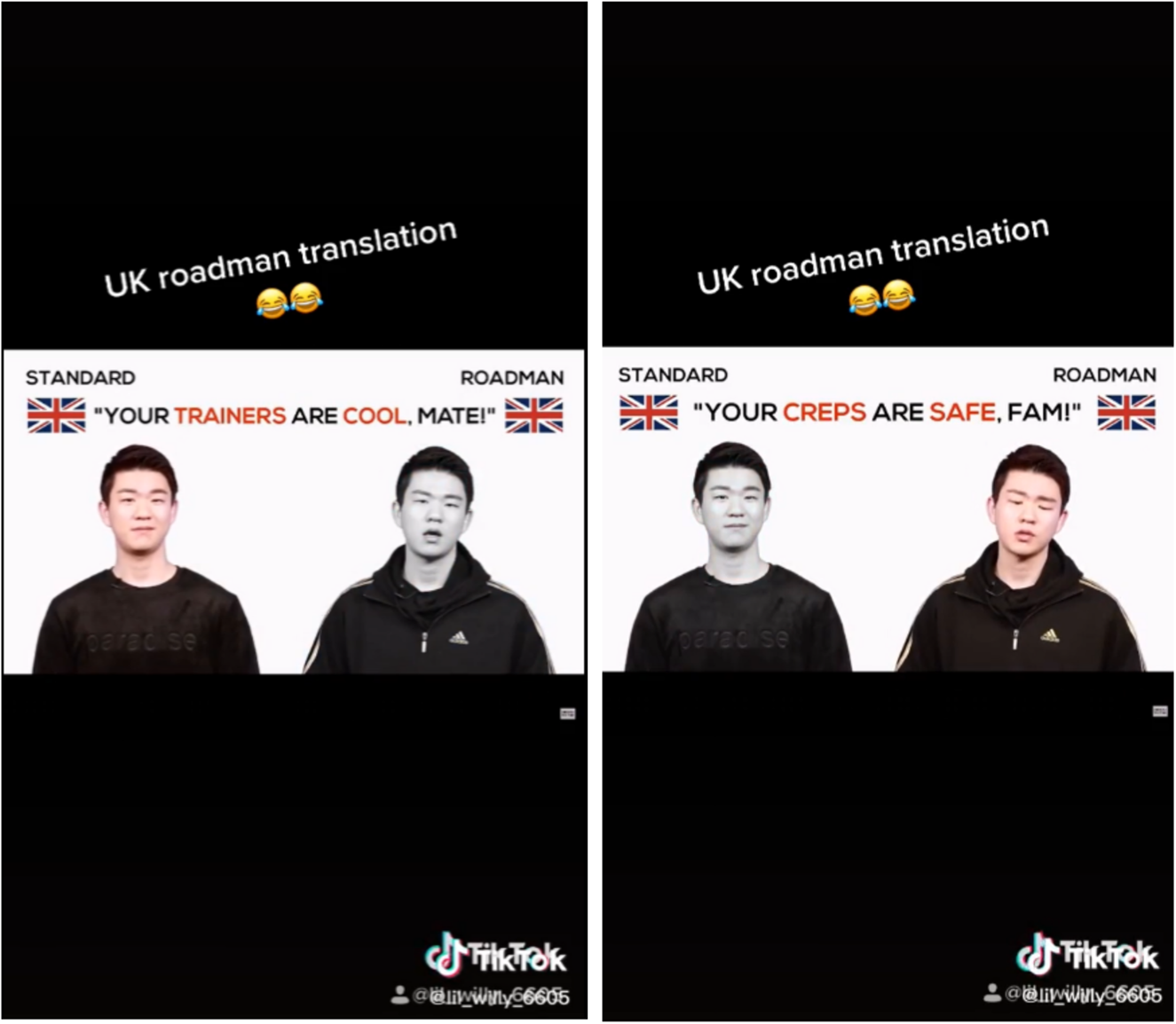

The recontextualisation of MLE is perhaps most apparent in videos which make explicit reference to an MLE-style that is erroneously labelled ‘roadman dialect/language/English’. A case in point is the video in Figure 4 in which the user ‘translates’ sentences from ‘Standard [English]’ (e.g. ‘your trainers are cool, mate’) to ‘Roadman [English]’ (e.g. ‘your creps are safe, fam’). As a type of linguistic stylisation, the actor performs the roadman through an assemblage of MLE features, in this instance by ‘translating’ trainers to creps, cool to safe, and mate to fam. Note, however, that none of the social qualities or dispositions of the roadman previously examined in other parodic videos (e.g. crime, aggression) are referenced, yet the speech style that is stylised—MLE—is nevertheless labelled as ‘Roadman [English]’.

Figure 4. ‘UK roadman translation’.

Before elaborating my arguments, it is necessary to reiterate that this label or characterological figure did not originate in social media nor is it specific to digital contexts. Although I have focussed on TikTok videos here, as discussed earlier, the roadman is widespread in popular discourse. Indeed, similar themes are referenced by the comedian Michael Dapaah in his portrayal of ‘Big Shaq’ (or ‘Roadman Shaq’), well known for his 2017 parodic grime track ‘Man's not hot’.

Nevertheless, I focus on social media data to demonstrate the coherence of metapragmatic discourses which contribute to the linkage between the roadman and certain social and linguistic qualities. Given that (social) media are considered powerful agents of socialization (Agha Reference Agha2007; Mortensen et al. Reference Mortensen, Coupland and Thogersen2017), I argue that these representations are likely to have implications for MLE speakers and the types of social meanings that are associated with this speech style. The mediatisation of this identity is notable given that, in the participatory environments of social media through memetic remixing and (re)circulation (Shifman Reference Shifman2013), users critique and circulate the social discourses that inform this identity, thus establishing new indexical links between MLE and the roadman persona (see also Androutsopoulos Reference Androutsopoulos, Tannen and Trester2013).

These issues become particularly problematic when we consider that social media enables users to engage with translocal communities and content. Subsequently, #roadman parodies transcend the fixed time-space boundaries of the traditional ‘speech community’, such that users who do not have habitual contact with MLE speakers engage with and contribute to the circulation, production, and reception of metapragmatic discourses. Indeed, several videos in the corpus were produced by users outside of the UK, such as creators in America and Australia—countries where there are unlikely to be large numbers of MLE speakers.

Subsequently, the identities, themes, and stances that typify #roadman videos acquire the potential to become internalised as characteristics of all MLE speakers. This erroneous connection is made explicit in the comments section of videos by MLE-speaking TikTok creators who do not claim this identity nor post #roadman parodies. For instance, extract (8) is taken from the comment section of a video collected during the digital ethnography for this project. In the video, the user describes the chemical reaction of sodium with water. His speech exhibits a number of MLE features including TH-stopping, styll, bare ‘lots’ and the phrase mad ting ‘crazy’.

(8)

In the comments, User 1 is seen to make an erroneous and essentialised connection between the individual (a Black TikTok creator), his speech style (MLE), and his assumed identity (a roadman) by stylising an imagined sentence characterised by several MLE features. The assessment is categorically rejected by Users 2 and 3, who call out the users’ problematic assessment, with User 3 arguing that it's just ‘slang’Footnote 4 which “doesn't make him a roadman”. This interaction signals a type of ‘indexical conflict’ triggered by the recontextualisation of MLE: the two socio-indexical meanings are in competition. On the one hand, MLE is as a variety habitually and authentically spoken by a particular demographic (comments by Users 2 and 3), and on the other, it is also ideologically associated with a particular subcultural orientation—Road culture—and an enregistered identity—the roadman (comment by User 1). Thus, this interaction (and indeed others), suggest a potential oversimplification of the indexical links that individuals make between this variety and its social meanings.

A further issue which complicates this matter is that it is possible that some individuals could stylistically adopt aspects of the enregistered style as a type of ‘commodity register’ (Agha Reference Agha2011) to index their alignment with either the roadman identity or road culture more generally. As Boakye (Reference Boakye2019) observes, the roadman identity does maintain a type of covert prestige for some largely due to the substantial influence of Black culture in the development of contemporary British youth culture. Today, the ‘road’ aesthetic and style (e.g. grime and other ‘urban’ music genres, athletic clothing, streetwise attitude) have become popularised in mainstream youth culture (cf. AAVE and hip hop; Cutler & Røyneland Reference Cutler, Røyneland, Nortier and Svensen2015). This type of prestige is alluded to in extract (9), a theatrical stylisation performed by a user (Davina) from the North East of England. All individuals are White.

(9) ‘coming back to your brother and his roadman mates like’

In the scene, Davina returns home to the boys ‘skanking’—a form of dance originating in Jamaica—to a drum and base (D'n’B) track—a genre of music derived from ‘Jungle’ which itself is defined as a Black British interpretation of hip hop (Zuberi & Stratton Reference Zuberi and Stratton2014). The extract contains several MLE features (e.g. my G, safe, mandem) which are, as I have demonstrated, enregistered components of the roadman style. The identity label is also explicitly referenced in the video title. As in Figure 4, none of the themes of crime or violence examined throughout this article are explicitly referenced here. Rather, the constructed dialogue appears to reference the boys’ positive alignment and engagement with aspects of Black British culture, for example, listening to D'n’B, skanking, and using features of MLE (see also Drummond Reference Drummond2018). Subsequently, this example (and others), appear to allude to the possibility that individuals who are seen to positively engage with aspects of Black culture may adopt stylistic elements of the roadman persona to index an appreciation of ‘Black cool’ and signal their alignment with this cultural orientation (see also Chun Reference Chun2013; Boakye Reference Boakye2019).

CONCLUSION

This article has examined the performance of a ‘characterological figure’ (Agha Reference Agha2003)—the roadman—that is linked to the multiethnolect, MLE, in parodic videos uploaded to the social media platform TikTok. Specifically, I have analysed the ways in which linguistic features characteristic of MLE (e.g. pronominal man, discourse-pragmatic styll, extremely fronted /uː/) and tropes of personhood (e.g. aggression, hyper-masculinity, a streetwear aesthetic) are co-opted and stylised in performances of the roadman. I have argued that, as a memetic genre (Shifman Reference Shifman2013), #roadman parodies exploit semiotic markers that are ideologically associated with Black British working-class youth.

Further, I have argued that roadman stylisations can shed light on the dynamics of ethnicity, race, and language in the UK today (see Rampton Reference Rampton1995; Bucholtz & Lopez Reference Bucholtz and Lopez2011; Jaspers Reference Jaspers2011). Specifically, I have demonstrated that the coherence of the metapragmatic discourses referenced in #roadman videos infers that a subset of MLE features have become ‘recontextualised’ (Bauman & Briggs Reference Bauman and Briggs1990) from an everyday speech style authentically used by working-class speakers living in inner-city neighbourhoods in London to a supralocal style that is associated both with a specific subcultural orientation (road culture) and social identity (the roadman), thus signalling a type of ‘raciolinguistic enregisterment’ (Rosa & Flores Reference Rosa and Flores2017). This process is comparable to the recontextualization of AAVE wherein features of this style have become linked with a particular cultural engagement (hip hop; Alim Reference Alim, Bloomquist, Green and Lanehart2015), but it is distinct in that this is orientation explicitly references (Black) British experiences and cultures, for example, grime.

Finally, I have argued that, as these parodies are uploaded to the hyper-networked environment of social media, roadman performances are circulated and consumed by audiences beyond the fixed space-time boundaries of the MLE ‘speech community’ (cf. Cheshire et al. Reference Cheshire, Kerswill;, Fox; and Torgersen2011). Subsequently, through the mediatisation of this characterological figure, #roadman performances contribute to ‘sociolinguistic change’ (Androutsopoulos Reference Androutsopoulos2014) as users (re)produce racialized meanings that transfer from a specific person-type to the broader speech style of MLE. It is therefore imperative for future research on MLE/MBE to examine not just speakers’ everyday linguistic practices, but also the ways in which those practices resist, engage with, and/or reference broader metapragmatic discourses that are pervasive in broader (digital) contexts of use.