Psychotic experiences are commonly endorsed by individuals in the general population. Reference Linscott and van Os1–Reference Johns, Cannon, Singleton, Murray, Farrell and Brugha3 These experiences include hallucinations or delusions that ‘may or may not be bizarre, engender distress, draw attention or prompt help seeking … and may be appraised as clinically relevant symptoms or as subclinical, not reaching a threshold of clinical relevance’. Reference Linscott and van Os1 Nevertheless, psychotic experiences may lie on a continuum with psychotic disorders, as they share risk factors with schizophrenia, Reference van Os, Hanssen, Bijl and Ravelli4 increase the risk of future psychotic disorders Reference Hanssen, Bak, Bijl, Vollebergh and van Os5,Reference Kaymaz, Drukker, Lieb, Wittchen, Werbeloff and Weiser6 and are associated with adverse health and social outcomes. Reference Mojtabai7–Reference Sharifi, Bakhshaie, Hatmi, Faghih-Nasiri, Sadeghianmehr and Mirkia9 Psychotic experiences have also been associated with increased risk of mortality in older adults with cognitive disorders Reference Lopez, Becker, Chang, Sweet, Aizenstein and Snitz10 and increased risk of suicide attempts. Reference Kelleher, Corcoran, Keeley, Wigman, Devlin and Ramsay11 However, little is known about the risk of all-cause and specific causes of mortality associated with psychotic experiences in the general population.

The association of psychotic experiences with mortality is of particular interest as past research has consistently found a higher mortality rate among individuals with psychotic disorders, especially schizophrenia. Reference Saha, Chant and McGrath12,Reference Suvisaari, Partti, Perala, Viertiö, Saarni and Lönnqvist13 If psychotic experiences lie on a continuum with psychotic disorders and share the same underlying risk factors and/or consequent adverse health outcomes (such as unhealthy life style and higher risk of physical health conditions), then individuals with psychotic experiences could be expected to have a higher mortality risk compared with those without psychotic experiences. This study examined the association between mortality and psychotic experiences using data from participants in the baseline Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) survey conducted in the early 1980s, linked to mortality data up until 2007. We hypothesised that: (a) the risk of all-cause and specific causes of mortality will be greater among individuals with lifetime psychotic experiences than those without, (b) the association will not be entirely explained by the presence of psychiatric disorders, and (c) there will be a dose–response relationship between the number of psychotic experiences and mortality.

Method

Study population

The baseline sample was from four of the five sites of the ECA study conducted in 1980–83, the methodology of the ECA is described elsewhere. Reference Eaton, Holzer, Von Korff, Anthony, Helzer and George14 In brief, individuals 18 years old or older not living in institutions were recruited from New Haven, Connecticut; Baltimore, Maryland; St Louis, Missouri and Durham, North Carolina through a probabilistic random sampling design (n = 15 440). Older adults were oversampled at the New Haven and Baltimore sites. The overall response rate across sites ranged from 77 to 79%. The Los Angeles site was not included in this study because identifying data required for linkage to the National Death Index (NDI) were discarded. We excluded 391 (2.5%) participants from the total sample of 15 440 for one or more of the following reasons: lack of information on age at the time of death from the NDI (n = 219); age of entry into the study being equal to the recorded age of death in the NDI (n = 43); and age at death or age at follow-up (if alive, see below) being less than 18 or more than 105 years (n = 147). We reasoned that participants whose projected age in 2007 was over 105 years were most likely deceased in 2007, even though not recorded in the NDI or other sources. The excluded cases were mostly female (55.2%, n = 216) and White (67.3%, n = 263); 15 (3.8%) reported psychotic experiences at baseline, and 298 (76.2%) were ascertained to be deceased in 2007. Analyses were limited to the remaining 15 049 (97.5%). The ECA mortality study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the four study sites.

Assessment of vital status

Vital status was ascertained primarily by linking the baseline ECA data with NDI vital statistics data. The methods used for this linkage are described in detail elsewhere. Reference Eaton, Roth, Bruce, Cottler, Wu and Nestadt15 Briefly, for each individual in the baseline interview, matches were obtained from the NDI database for deaths up to and including the year 2007. The following information was used for linking data to the NDI database: last name, first name, gender, ethnicity, date of birth, social security number, father's surname and last state of residence. Other sources for all-cause mortality included the Social Security Death Index and information from the follow-up of the Baltimore ECA. Reference Eaton, Kalaydjian, Scharfstein, Mezuk and Ding16 As the match between the ECA and NDI data was not perfect in all cases, we developed a scale for quality of matches (definite, near definite, very probable, probable, likely, possible or potential). This scale is described in more detail elsewhere. Reference Eaton, Roth, Bruce, Cottler, Wu and Nestadt15

Participants were classified as alive by the end of follow-up (31 December 2007) if they were not matched through the NDI or other sources. For these individuals we calculated the apparent age at follow-up by adding 24–27 years to the baseline age (depending on the year of interview: 1980–1983). Age at death was calculated from the date of birth and the recorded date of death. We also obtained the primary underlying causes of death (disease or injury that initiated events resulting in death) from the NDI database if available. The underlying cause was available for 6045 (91.2%) out of the 6626 individuals ascertained to be deceased at follow-up. The causes of death were recorded using the ICD-9 codes for death from 1980 to 1998 and the ICD-10 codes for deaths in 1999 or later. 17,18 The causes were categorised as natural (circulatory, neoplasms, other natural) and unnatural (suicide, other unnatural).

Baseline measures

Psychiatric conditions and psychotic experiences were assessed using the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) Reference Robins, Helzer, Croughan and Ratcliff19 based on the DSM-III criteria. 20 The DIS is designed for use by non-clinician interviewers and has been shown to be a reliable and valid instrument. Reference Robins, Helzer, Croughan and Ratcliff19 Eleven questions related to lifetime psychotic experiences were asked in the schizophrenia section of the DIS including nine questions about delusional beliefs and two about hallucinations (Table 1). Any positive response was followed by a series of probes to rule out that the experience was trivial, caused by medical conditions, substance-related or had plausible explanations. Only delusional beliefs that were judged by the interviewers to be primary (i.e. not under the influence of drugs/alcohol or general medical conditions) and without plausible explanations, and primary hallucinatory experiences, were included as psychotic experiences in the main analysis. We also computed the total number of psychotic experiences (psychotic experiences count, range 0–11). In further analyses we included both primary and secondary psychotic experiences.

Table 1 List of the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) items used for ascertainment of psychotic symptoms and prevalence estimates in 15 049 participants

| Any positive response a | Primary psychotic symptoms (psychotic experiences) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIS items | n | Weighted % (95% CI) | n | Weighted % (95% CI) |

| Have you ever believed people were watching you or spying on you? | 1772 | 13.2 (12.5–14.0) | 195 | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) |

| Was there ever a time when you believed people were following you? | 894 | 6.5 (6.0–7.1) | 97 | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) |

| Have you ever believed that someone was plotting against you or trying to hurt you or poison you? |

606 | 4.1 (3.7–4.5) | 127 | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) |

| Have you ever believed that someone was reading your mind? | 230 | 1.8 (1.5–2.1) | 78 | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) |

| Have you ever believed you could actually hear what another person was thinking, even though he was not speaking or believed that others could hear your thoughts? |

541 | 4.0 (3.6–4.5) | 129 | 0.9 (0.70–1.1) |

| Have you ever believed that others were controlling how you moved or what you thought against your will? |

192 | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 88 | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) |

| Have you ever felt that someone or something could put strange thoughts directly into your mind or could take or steal your thoughts out of your mind? |

205 | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 72 | 0.4 (0.3–0.6) |

| Have you ever believed that you were being sent special messages through television or the radio? |

143 | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 54 | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) |

| Other volunteered delusions | 45 | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) | 25 | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) |

| Have you ever had the experience of seeing something or someone that others who were present could not see – that is, had a vision when you were completely awake? |

964 | 6.2 (5.7–6.7) | 329 | 2.0 (1.8–2.3) |

| Have you more than once had the experience of hearing things other people couldn't hear, such as a voice? |

668 | 4.7 (4.3–5.2) | 305 | 2.0 (1.8–2.4) |

| Any symptom | 3474 | 24.7 (23.8–25.7) | 855 | 5.5 (5.1–6.0) |

a. Includes the following categories: non-significant symptoms, associated with alcohol or substance use, associated with medical conditions, having plausible explanation and primary psychotic symptoms.

Although the sensitivity of the DIS diagnosis of schizophrenia in ECA has been shown to be low when compared with the gold standard of clinician-administered semi-structured interviews, the DIS has better sensitivity and specificity for detecting psychotic symptoms. Reference Eaton, Romanoski, Anthony and Nestadt21,Reference Helzer, Robins, McEvoy, Spitznagel, Stoltzman and Farmer22 Furthermore, test–retest reliability studies have indicated acceptable consistency in reports of lifetime schizophrenia symptoms. Reference Escobar, Randolph, Asamen and Karno23

The DIS diagnoses for this study included schizophrenia spectrum disorders (schizophrenia; schizophreniform disorder), depressive disorders (major depression, dysthymia), bipolar disorder, phobic disorders (simple phobias, agoraphobia, social phobia), obsessive–compulsive disorder, panic disorder, alcohol use disorders (alcohol misuse or dependence), other substance use disorders (misuse of or dependence on barbiturates, opioids, cocaine, hallucinogens, cannabis or methamphetamines) and antisocial personality disorder, all based on the DSM-III criteria. In addition, history of any psychiatric hospital admission was included to improve sensitivity of the DIS for detection of severe mental disorders. Cognitive impairment was assessed by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHugh24 adopting a cut-off of 23 or less as indicative of significant cognitive impairment.

Sociodemographic variables in the analyses included age, gender, ethnicity, education and marital status, which are found in past research to be associated with mortality. Reference Kallan25 Education was ascertained as the highest grade in school or year of college completed by the individual. Occupational status score (percentile) was based on the categorisation of current or most recent job following the 1980 US Census Occupational Classification System. The classification was converted to percentiles ranking for occupations using a methodology developed by Nam et al. Reference Nam and Powers26,Reference Nam, LaRocque, Powers and Holmberg27

Statistical analysis

Survival models were used for the analyses of time to death. Participants who were not recorded as deceased by 2007 were assumed to be alive and censored in the analyses. As there were only 10 deaths below age 25 years, we limited the analyses to years after age 25. Thus, participants younger than 25 years at baseline contributed to the analysis only with years after age 25. Initially we attempted using a Cox proportional hazard regression model to quantify the relationship of psychotic experiences with time to death. However, examination of the log–log plots and goodness-of-fit statistics based on Schoenfeld residuals did not support the proportionality of hazards assumption of Cox regression. Therefore, we tested a number of parametric models, among which the generalised gamma model Reference Cox, Chu, Schneider and Munoz28 had the smallest Akaike information criterion (AIC) value and was chosen (see online Table DS1). The accelerated failure time in this model describes stretching or shrinkage of survival time as a function of predictor variables. The generalised gamma distribution is defined by three parameters allowing for greater flexibility in distribution of hazards, including beta (β), sigma (σ) and kappa (κ), corresponding to location, scale and shape, respectively (for further information see Cox et al Reference Cox, Chu, Schneider and Munoz28 ). The generalised gamma analysis does not assume proportionality of hazards. We used the generalised gamma analysis both to test the association between psychotic experiences and mortality and to quantify survival times.

Analyses were first performed after adjustment for gender and ethnicity that clearly are antecedent to psychotic experiences. The analyses were repeated after adjusting for all covariates (socio-demographics and psychiatric conditions entered individually), which may have preceded or followed the onset of psychotic experiences. We further examined the interaction terms of the covariates with the main predictors. Since no significant interaction terms were found, we removed these terms from the models. We also allowed the ancillary parameters of the generalised gamma distribution (the scale (σ) and the shape (β)) to be modified by the covariates. As the overall results of the generalised gamma analyses were not substantively different from the Cox proportional hazard regressions, we present adjusted Cox hazard ratios along with the generalised gamma coefficients (β). Analyses were repeated to test the association of psychotic experiences with each category of specific causes of mortality. For each cause, individuals who had died of other causes (competing causes) were censored.

In further analyses, we assessed whether the association of psychotic experiences with mortality persisted after (a) excluding all individuals with a DIS schizophrenia spectrum disorder instead of adjusting for these disorders in the regression model and (b) expanding the definition of psychotic experiences to include individuals with both primary and secondary psychotic experiences (i.e. those whose psychotic experiences was judged to be associated with drug misuse and/or medical condition). Separate survival models were fitted for each of these analyses. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 12. Sample weights were used to compensate for potential biases introduced by sampling design and non-response. The Taylor series linearisation method was used to adjust standard errors. All reported estimates are weighted unless otherwise indicated. A P<0.05 statistical significance level was used.

Sensitivity analysis

To assess the potential impact of late-life cognitive deficits, which may be associated with both psychotic experiences and increased mortality, Reference Lopez, Becker, Chang, Sweet, Aizenstein and Snitz10 we repeated the analyses after excluding participants who were 75 years old or older at baseline. We repeated the analyses a second time, after adjusting the analyses for significant cognitive impairment based on MMSE.

We conducted further sensitivity analyses to assess the potential impact of quality of NDI matches. For this, we repeated the analyses after eliminating observations with a less than ‘likely’ match. Among all cases with rated quality of matching, less that 10% were rated as less than a ‘likely’ match.

Results

At baseline, the average age of the 15 049 participants was 43.0 years, 53.8% (n = 9087) were female, 58.1% (n = 7211) were married, 19.6% (n = 5005) were widowed or divorced, and 22.3% (n = 2817) had never been married. The majority of the participants were non-Hispanic White (n = 10 581, 74.5%); 22.5% (n = 4051) were non-Hispanic Black and 3.0% (n = 387) were from other ethnicities. A majority (64.2%, n = 8375) had 12 or more years of education. In total, 855 (5.5%) participants reported one or more psychotic experiences (Table 1). Of these, 629 (76.5%) met the criteria for at least one of the study's DSM-III disorders; 186 (27.6%) met the criteria for a schizophrenic spectrum disorder. Proportions of individuals with more than two comorbid disorders and history of psychiatric hospital admission were higher among the individuals with psychotic experiences than those with any psychiatric disorder with or without psychotic experiences (online Table DS2).

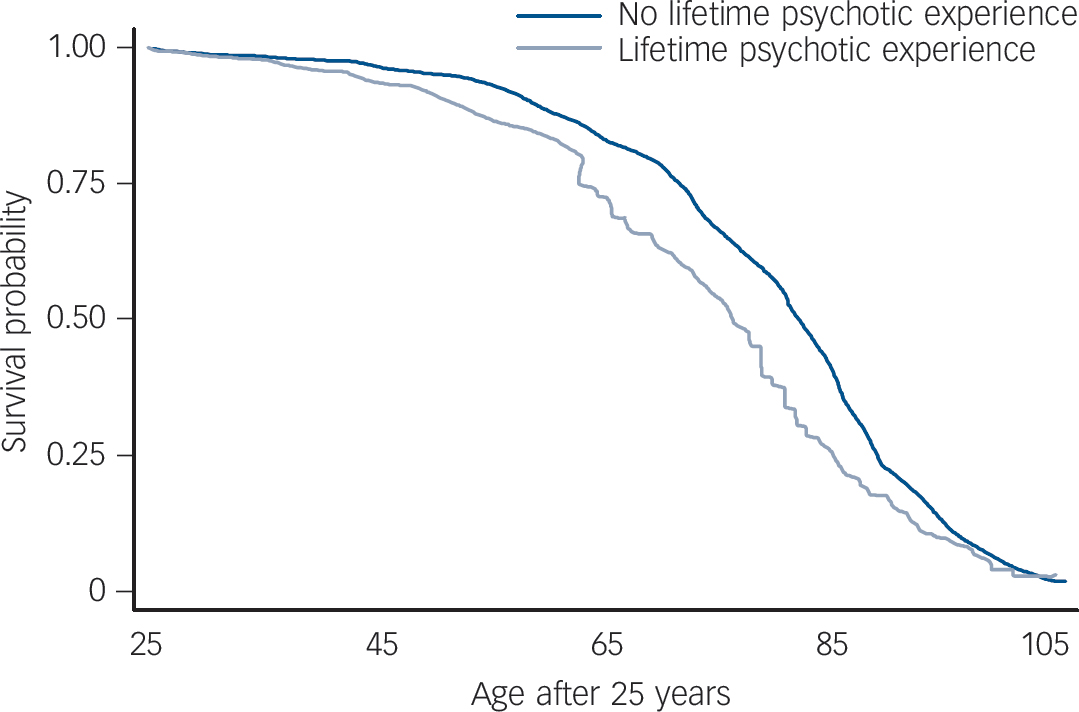

The 15 049 participants provided a total of 293 769 life-years of observation. During the follow-up period, 6626 (44.0%) of the 15 049 ECA participants were ascertained to be deceased. The average age of death in participants with psychotic experiences (67.5 years, 95% CI 65.3–69.6) was lower than for those without psychotic experiences (74.0 years, 95% CI 73.5–74.5). The Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the groups with and without psychotic experiences are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the groups with and without lifetime psychotic experiences in 15 049 participants.

Because there were only 10 deaths below age 25 years, we limited the analyses to years after age 25. Thus, participants younger than 25 years at baseline contributed to the analysis only with years of life after age 25.

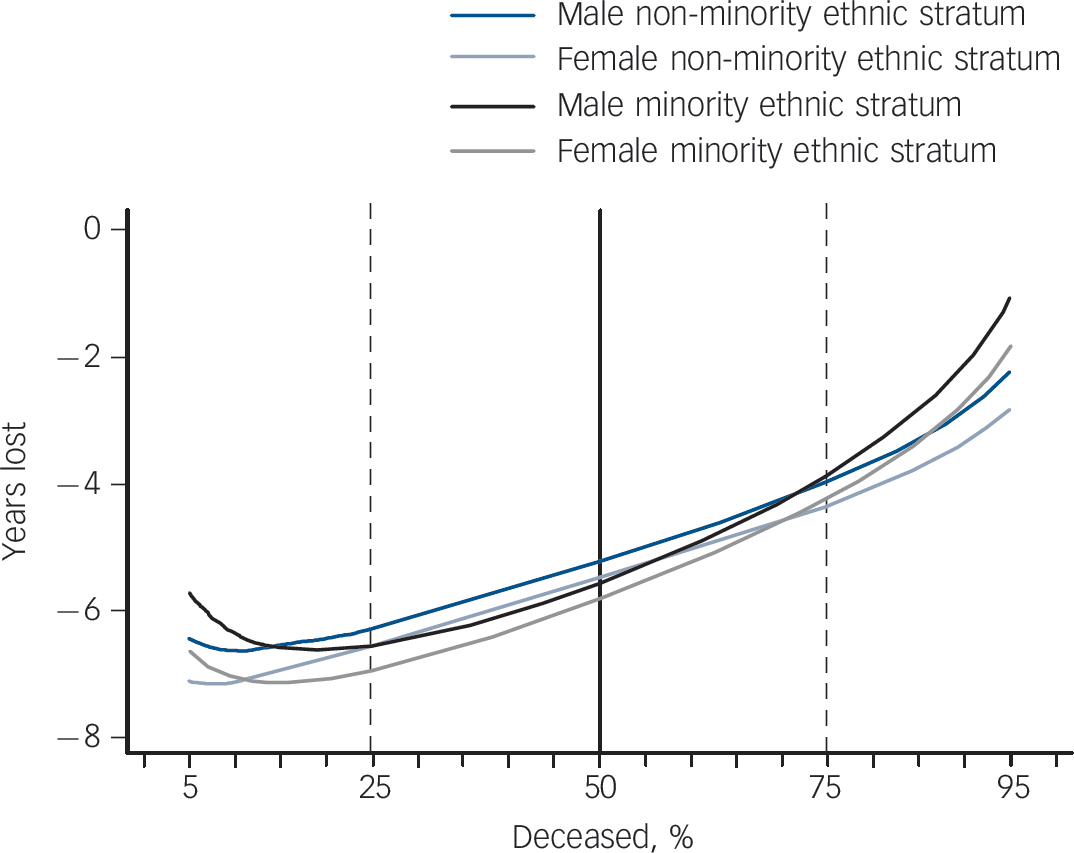

In generalised gamma models, lifetime psychotic experiences were associated with increased hazard of all-cause mortality after adjustment for gender and ethnicity (Table 2); the association persisted after including all covariates (Table 2). These results were corroborated in Cox regression models, in which the gender and ethnicity-adjusted hazard ratio (HR) associated with psychotic experiences was 1.41; the hazard ratio was reduced to 1.23 after adjustments for all sociodemographic and psychiatric variables (Table 2). The median and percentile ranges of years lost in each gender and ethnicity stratum are presented in Fig. 2. The predicted median years lost associated with psychotic experiences were over 5 years in groups stratified by gender and ethnicity (5.2–5.8 years). In addition, male gender, less education, lower occupational status, not being married, minority ethnic status, phobic disorders, alcohol and substance use disorders and anti-social personality disorder were associated with increased risk of mortality in generalised gamma regression analyses (online Table DS3).

Table 2 Association of lifetime psychotic experiences with all-cause and specific causes of mortality adjusted for the covariates examined by Cox proportional hazard and generalised gamma models in 15 049 participants

| Deceased | Cox model, HR (95% CI) | Generalised gamma model, β (s.e.) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime psychotic experiences | No lifetime psychotic experiences | Adjusted for gender and ethnicity |

Adjusted for all covariates a |

Adjusted for gender and ethnicity |

Adjusted for all covariates a |

|||

| Causes of mortality | n | Weighted % (95% CI) | n | Weighted % (95% CI) | ||||

| All-cause mortality | 322 | 30.5 (26.8–34.4) | 5910 | 29.8 (28.8–30.8) | 1.41*** (1.21–1.66) | 1.23* (1.03–1.46) | −0.07*** (0.02) | −0.05* (0.02) |

| Specific-cause mortality b | ||||||||

| Natural causes | 273 | 25.8 (22.4–29.7) | 5235 | 27.3 (26.3–28.2) | 1.33** (1.13–1.58) | 1.18 (0.98–1.44) | −0.05** (0.02) | −0.04 (0.02) |

| Circulatory | 123 | 9.6 (7.7–12.1) | 2423 | 11.8 (11.1–12.4) | 1.25 (0.98–1.60) | 1.19 (0.90–1.57) | −0.38 (0.02) | −0.34 (0.02) |

| Neoplasms | 66 | 8.4 (6.2–11.3) | 1208 | 7.3 (6.7–7.9) | 1.51* (1.09–2.10) | 1.33 (0.92–1.92) | −0.12* (0.05) | −0.08 (0.06) |

| Other natural | 84 | 7.8 (5.9–10.3) | 1593 | 8.2 (7.6–8.7) | 1.28 (0.94–1.75) | 1.05 (0.73–1.51) | −0.04 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.04) |

| Unnatural causes | 18 | 2.8 (1.6–4.7) | 168 | 11.0 (8.8–13.5) | 2.67** (1.46–4.87) | 1.69 (0.86–3.34) | −0.87** (0.31) | −0.45 (0.31) |

| Suicide | 5 | 1.0 (0.4–2.4) | 19 | 0.1 (0.1–0.2) | 9.16*** (3.19–26.29) | 2.28 (0.36–14.41) | −2.51** (0.79) | −0.52 (0.56) |

| Other unnatural | 13 | 1.8 (1.0–3.5) | 149 | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 1.91 (0.92–3.98) | 1.5 (0.71–3.19) | −0.55 (0.34) | −0.35 (0.36) |

a. Including gender, ethnicity, marital status, education, schizophrenia spectrum disorders, depressive disorders, bipolar disorder, phobic disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder, panic disorder, alcohol use disorders, other substance use disorders, antisocial personality disorder and any psychiatric hospital admission.

b. Categories of specific primary underlying causes of mortality according to ICD-9 and ICD-10 classifications.

* P<0.05

** P<0.01

*** P<0.001.

Fig. 2 Years of life lost associated with lifetime psychotic experiences as predicted by the generalised gamma model stratified according to gender and ethnicity in 15 049 participants.

The area between the dashed lines represents the interquartile range and the solid line represents the median.

The majority of deaths in both participants with and without psychotic experiences were related to natural causes. Psychotic experiences were associated with increased risk of mortality as a result of both natural and unnatural causes in the models adjusting for gender and ethnicity. Among specific causes, psychotic experiences were associated at a statistically significant level with deaths because of both suicide and neoplasms. The association of psychotic experiences with mortality as a result of specific causes was not statistically significant in models adjusting for all variables, although the direction of associations did not change across models (Table 2).

The number of psychotic experiences (psychotic experiences count) was associated with mortality in models adjusting for gender and ethnicity (β = −0.04, 95% CI −0.06 to −0.02, P<0.001) and for all covariates (β = −0.03, 95% CI −0.05 to −0.01, P<0.01) (online Table DS4). Furthermore, there was a statistically significant trend across psychotic experiences count in both models (z = 37.1, P<0.001 and z = 25.2, P<0.001, respectively) – the larger the psychotic experiences count, the higher the risk of death.

Further analyses were performed to assess whether the associations persist after (a) exclusion of individuals with a DIS schizophrenia spectrum disorder and (b) expanding the definition of psychotic experiences to include both primary and secondary psychotic experiences. The associations observed in these analyses did not differ substantively from those in the main analyses reported here (online Table DS5 and online Fig. DS1). The results also did not substantively change in sensitivity analyses taking into account the potential impact of late-life cognitive deficits and varying quality of NDI matches. Psychotic experiences remained significantly associated with mortality after excluding 878 (5.8%) participants who were 80 years old or older, after adjusting for significant cognitive impairment and when using a more stringent NDI match quality level (data not shown).

Discussion

In this large, multisite, community sample, 5.5% of participants reported lifetime psychotic experiences. Moreover, presence of lifetime psychotic experiences was associated with increased risk of death in a 24–27 year follow-up. Past research has found associations between psychotic disorders, especially schizophrenia, and increased mortality risk. Reference Saha, Chant and McGrath12,Reference Suvisaari, Partti, Perala, Viertiö, Saarni and Lönnqvist13 Past research has also identified associations between psychotic experiences in adolescence and the risk of future suicide. Reference Kelleher, Corcoran, Keeley, Wigman, Devlin and Ramsay11 However, to our knowledge no previous studies examined the association of psychotic experiences with all-cause mortality in adulthood.

The majority of the participants with psychotic experiences in this study also met the criteria for at least one comorbid DSM-III disorder. Increased risk of mortality has been previously reported among individuals with mental disorders. Reference Eaton, Roth, Bruce, Cottler, Wu and Nestadt15,Reference Ramsey, Spira, Mojtabai, Eaton, Roth and Lee29 However, the association of psychotic experiences with mortality remained statistically significant even after controlling for psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia and mood disorders. Therefore the increased risk cannot be attributed solely to psychiatric disorders. Although, in some of these individuals, psychotic experiences at baseline might have been the prodromal manifestations of a future psychotic disorder, such as schizophrenia. Psychotic experiences appeared to be strongly associated with suicide deaths as reflected in the high HR of 9.16. However, the association was attenuated (HR = 2.28) and rendered statistically non-significant when adjusted for psychiatric conditions. Therefore, increased risk of suicide associated with psychotic experiences may at least in part be explained by comorbid psychiatric disorders. However, the number of recorded suicides as the cause of death was small. Future studies with larger samples are needed to examine whether psychotic experiences increases risk of death by suicide independent of comorbid non-psychotic psychopathology as suggested by past research. Reference Kelleher, Corcoran, Keeley, Wigman, Devlin and Ramsay11 The risk of death as a result of accidents was also slightly higher among those with psychotic experiences, however the association was not statistically significant. There are some indications of incorrect labelling of suicides as accidents in the ascertainment of the cause of death; because of the difficulties in distinguishing some deaths because of accidents from suicides some investigators have suggested that these categories be combined. Reference Stanistreet, Taylor, Jeffrey and Gabbay30

Past research has found that the increased mortality associated with various psychiatric disorders (especially schizophrenia) is mainly attributable to natural causes, and is mediated by medical comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases, which in turn are associated with life-style factors such as smoking and sedentary lifestyle. Reference Suvisaari, Partti, Perala, Viertiö, Saarni and Lönnqvist13,Reference Lemogne, Nabi, Melchior, Goldberg, Limosin and Consoli31 We observed a similar pattern in the distribution of causes of death associated with psychotic experiences. Furthermore, increased use of tobacco and alcohol Reference Saha, Scott, Varghese, Degenhardt, Slade and McGrath32,Reference van Gastel, Maccabe, Schubart, Vreeker, Tempelaar and Kahn33 and a higher prevalence of lifetime medical conditions and health problems Reference Moreno, Nuevo, Chatterji, Verdes, Arango and Ayuso-Mateos8 have been observed in individuals with psychotic experiences. Unfortunately, the ECA did not assess lifestyle factors such as smoking and diet that might explain the increased mortality. On the other hand, individuals with psychotic experiences, similar to patients with other psychiatric conditions, may not receive adequate physical healthcare, hence, medical illnesses may be poorly detected and treated which, in turn, may increase mortality risk. Reference Mojtabai, Cullen, Everett, Nugent, Sawa and Sharifi34

Alternatively, both psychotic experiences and mortality may be related to a third factor, such as social adversity and life stressors. These stressors may prolong and exacerbate psychosis proneness on the one hand Reference van Os, Linscott, Myin-Germeys, Delespaul and Krabbendam35,Reference Collip, Wigman and Myin-Germeys36 and contribute to premature mortality, on the other hand. Reference Kopp and Rethelyi37 It is also possible that the psychotic experiences–mortality link involves a number of different mechanisms including both lifestyle factors and stress. Future research needs to investigate these mechanisms.

Strengths and limitations

Our study had important strengths. First, it examined the mortality risk in a large and diverse sample of community adults from four geographic regions. With few exceptions, Reference Suvisaari, Partti, Perala, Viertiö, Saarni and Lönnqvist13,Reference Lemogne, Nabi, Melchior, Goldberg, Limosin and Consoli31 past studies of the association of psychiatric disorders with mortality were not based on representative community samples. Prior studies typically are based on psychiatric registry- or hospital-based data-sets. However, individuals with psychotic experiences who have not received psychiatric treatment are not captured by such data sources. Second, the follow-up in this study was considerably longer (up to 27 years) than many past studies and together with a large sample size the study provided substantial person-years of observation. Third, we used a relatively novel and flexible procedure for survival analysis Reference Cox, Chu, Schneider and Munoz28 that is robust to assumptions regarding the proportionality of hazards.

Nevertheless, the study's limitations should be considered in interpreting the results. First, ascertainment of psychotic experiences was based on self-reports, which are prone to errors because of recall bias, poor insight, stigma and misunderstanding of the questions. However, self-report is the only possible method for ascertaining psychotic experiences in population surveys. Second, the DIS items capture a narrow definition of psychotic experiences. The prevalence of psychotic experiences might be higher if assessed using instruments with a broader definition of these experiences. Third, psychotic experiences may be indicators for other factors associated with increased mortality, such as severity of psychiatric illnesses. Consistent with this view, past research in community samples has shown that psychotic experiences are associated with higher levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms. Reference Sharifi, Bakhshaie, Hatmi, Faghih-Nasiri, Sadeghianmehr and Mirkia9 Similarly, in the present study, we observed a greater number of comorbidities and higher prevalence of psychiatric hospital admissions among participants with psychotic experiences. Finally, the ECA did not assess lifestyle factors (e.g. smoking and diet) or income that could influence the association with mortality.

Implications

In the context of the study's limitations, our findings support an association between psychotic experiences and increased risk of death in the general population. Moreover, the association of psychotic experiences with mortality remained statistically significant even after controlling for psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia and mood disorders; therefore, the increased risk cannot be attributed solely to psychiatric conditions at baseline. The dose–response associations suggest a possible causal link and the need for additional research to elucidate the association of psychotic experiences with increased risk of mortality. Much of the discussion on the public health burden of psychotic disorders is limited to schizophrenia and other psychotic conditions that meet the criteria for distinct DSM diagnoses. The findings from this study and other studies on the health and social consequences of the psychosis spectrum Reference Hanssen, Bak, Bijl, Vollebergh and van Os5–Reference Sharifi, Bakhshaie, Hatmi, Faghih-Nasiri, Sadeghianmehr and Mirkia9,Reference Saha, Scott, Varghese, Degenhardt, Slade and McGrath32,Reference van Gastel, Maccabe, Schubart, Vreeker, Tempelaar and Kahn33 suggest that psychotic experiences, which are more prevalent than specific psychotic disorders, are also associated with adverse social and health consequences. The link between psychosis, on the one hand, and social well-being and physical health, on the other hand, might be more widespread than suggested by prior research limited to psychotic disorders. If future research on the nature of the association between psychotic experiences and increased mortality proves a causal role for psychotic experiences, then additional research efforts are needed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying this association. Results from this longitudinal, population-based sample provide much-needed data for this understudied area.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant DA026652).

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Profesorr Alvaro Munoz for his helpful advice regarding the statistical analyses.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.