Introduction

Populism has been understood both as a threat and as a corrective to democracy (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012b). To the extent that it serves as a corrective, populism connects with the redemptive face of democracy, which is defined by faith in the idea that power should be given to the people, who should decide their own future through a direct expression of their will (Canovan, Reference Canovan1999). Carrying this argument to the individual level, the presence of populist ideas among citizens should encourage their political participation. In this paper, we submit this idea to empirical testing and argue that populist attitudes constitute a powerful motivation for citizens’ political participation, particularly if they are in disadvantaged socioeconomic positions.

By focusing on the primacy of popular sovereignty and by morally condemning the ruling elite, populism enhances feelings of identity, purpose, and moral outrage that have been found to be related to participation and, in particular, to non-institutional modes (Van Zomeren, Postmes and Spears, Reference Van Zomeren, Postmes and Spears2008; Aslanidis, Reference Aslanidis2016). Since ‘the people’ of populist politics are those that ‘consider themselves disenfranchised and excluded from political life’ (Panizza, Reference Panizza2005, p. 16), populist ideas will be more consequential for the less privileged, mobilizing particularly disadvantaged citizens who are more likely to identify themselves as ‘the people’ and to be responsive to populist arguments. Hence, populist attitudes are expected to be positively related not only to the probability of participating in politics but also to higher levels of political equality.

Based on survey data from nine European countries, our analyses find robust evidence in favour of a positive association between populist attitudes and non-institutional modes of political participation such as petition signing and the online expression of political views. The evidence regarding participation in demonstrations seems mixed and dependent on country characteristics, while for voting we find a null or a negative effect. In addition, our analyses suggest that the presence of populist attitudes increases participation particularly for individuals with low levels of education and income, narrowing (for education) and even reversing (for income) the traditional socioeconomic inequality in participation. We follow recent attempts to put motivations at the forefront of explanations for political behaviour (Miller and Saunders, Reference Miller and Saunders2016), while, at the same time, we speak to the traditional and abiding democratic dilemma of unequal participation (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1997). Our findings provide empirical evidence that some populist ideas can, indeed, have implications that help to correct some democratic deficiencies, as previous works have suggested.

The article is structured as follows. In the next section, we outline our arguments linking populist attitudes, political participation, and political equality. We then describe the data and the methods used. The fourth section presents the results of the empirical analysis. Finally, the last section concludes with the discussion of our main findings.

Populist attitudes, political participation, and political equality

Populist attitudes as a motivation to participate

We follow the minimal definition summarized by Mudde (Reference Mudde2004), for whom populism is a set of ideas that ‘considers society to be separated into two relatively homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ vs. ‘the corrupt elite’, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people’ (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004, p. 543). Two aspects of this definition stand out as particularly relevant for their potential mobilizing consequences. Populist attitudes involve a combination of a positive component (a defence of popular sovereignty) and a negative component (rejection of the establishment). Both may be expected to act as motivations for political participation for different reasons. We examine them in turn.

The popular sovereignty component of populism relates naturally to the idea that the people should be at the centre of politics and political decisions. While populism may be illiberal, it certainly has a determined democratic character, with the will of the people at the core of its values (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012b). Populism promises a better world through an implementation of the people’s will and the people’s action (Canovan, Reference Canovan1999). As such, populism shares a redemptive nature with radical and deliberative democratic theories (Pateman, Reference Pateman1970), where the ideal of unmediated citizens’ direct participation is a crucial political value.

Furthermore, populism can be understood as a collective action frame to construct a collective identity (the people) that challenges the elites (Aslanidis, Reference Aslanidis2016; Panizza, Reference Panizza2017). Social movement literature has highlighted the importance of identity, particularly for protest participation (Klandermans, Reference Klandermans2014). Social movements construct adversarial frames and identities that collectively share these frames. Interiorized populist ideas that oppose ‘the people’ against ‘the elite’ are expected to generate a feel of belonging to ‘the good people’ and an opposition against ‘the corrupt elite’. Hence populist ideas provide both identity and purpose (the people’s will against the elite), two important elements behind any process of political mobilization.

This brings about the second relevant component of populism: anti-elitism, which involves the sentiment that the political elite is corrupt and evil, and that it acts in accordance with its own benefits and contradicts the interests of the people (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004). While attitudes such as distrust (see, for instance, Hooghe and Marien, Reference Hooghe and Marien2012) or disaffection (Miller, Reference Miller1980; Torcal and Montero, Reference Torcal and Montero2006) are also negative attitudes towards political objects, anti-elitism is different because it has a moral character. While distrust and disaffection lead to apathy and reduce participation, anti-elitism generates moral outrage that is expected to increase participation.

From a populist perspective, the elite is not only incapable, untrustworthy, and distant, but also evil. Moralized attitudes have been found to enhance motivation to participate (Skitka and Bauman, Reference Skitka and Bauman2008; Skitka, Hanson and Wisneski, Reference Skitka, Hanson and Wisneski2017) and to reduce inhibitions against acting (Effron and Miller, Reference Effron and Miller2012; Ryan, Reference Ryan2017). In a context where politics is diminished and highly discredited to the point of being hated (Hay, Reference Hay2007), populist accounts of the political situation produce a necessary legitimized justification for becoming engaged. Perceptions of injustice and subsequent moral outrage have been found to be related to political engagement and, particularly, to protest (Van Zomeren, Postmes and Spears, Reference Van Zomeren, Postmes and Spears2008; Goodwin, Jasper and Polletta, Reference Goodwin, Jasper and Polletta2009; Van Stekelenburg and Klandermans, Reference Van Stekelenburg and Klandermans2010).

This populist critical view of the political elite is connected to emotional states of arousal and anger. While other negative emotions have been associated with populist attitudes (Demertzis, Reference Demertzis2006), the emotional underpinnings of populism seem to be related to feelings of anger rather than fear, whether in regard to populist attitudes in Spain (Rico, Guinjoan and Anduiza, Reference Rico, Guinjoan and Anduiza2017), populist radical right vote choice in France (Vasilopoulos et al., Reference Vasilopoulos, Marcus, Valentino and Foucault2018), or Euroscepticism in Britain (Vasilopoulou and Wagner, Reference Vasilopoulou and Wagner2017). Anger is the typical emotion that emerges from a situation where personal damage or the threat of damage is perceived as deriving from negligent behaviour on the part of an external agent in control. Anger has previously been found to enhance political participation to a greater extent than other emotions (Thompson, Reference Thompson2006; Valentino et al., Reference Valentino, Brader, Groenendyk, Gregorowicz and Hutchings2011; Weber, Reference Weber2012). It contributes to achieving insight and motivating action (Thompson, Reference Thompson2006). As far as populist attitudes are related to emotions of anger, they should predispose citizens to engage in active political behaviour rather than in apathetic passiveness.

In sum, populist attitudes involve an emphasis on the importance of a popular will directly expressed and a collective identity (the people) morally outraged by an evil elite. These elements can generate motivation to participate in politics through identity, purpose, and emotion. Therefore, we expect individuals with high levels of such attitudes to be more likely to participate in politics (Hypothesis 1).

Some works have addressed the relationship between participation and different political attitudes proximate or related to populism, but not populist attitudes themselves. For example, several authors have analysed the effect of discontent or support on stealth democracy (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002), on the willingness to participate or on preferences for participation (Webb, Reference Webb2013; Font, Wojcieszak and Navarro, Reference Font, Wojcieszak and Navarro2015). As attitudes towards participation differ significantly from actual participation, their findings cannot be generalized to actual behaviour. Other works have elaborated on the relationship between the cynical understanding of politics and populist angst (Stoker and Hay, Reference Stoker and Hay2017), but their analyses do not specifically assess the implications of these attitudes for participation. Other scholars have addressed how anti-party attitudes (Belanger, Reference Belanger2004) or distrust (Hooghe, Marien and Pauwels, Reference Hooghe, Marien and Pauwels2011; Hooghe and Marien, Reference Hooghe and Marien2012) affect actual behaviour (mostly turnout but also protest), yet again their focus has not been the study of populist attitudes. Among these works, results seem to point to the conclusion that trust in representative institutions enhances electoral or conventional participation, while distrust increases protest and grass-roots participation.

Getting somewhat closer to the concept of populist attitudes, Christensen (Reference Christensen2016) has analysed the effect of a combination of low support with high subjective empowerment on protest, finding a small positive effect robust to a large number of controls. Akkerman et al. (Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014) in the Netherlands and Stanley (Reference Stanley2011) in Slovakia have examined the relationship between populist attitudes and turnout, finding no significant effects. Despite this related evidence, the broader question of whether populist attitudes enhance political participation remains to be assessed for different modes in different contexts.

Populist attitudes as moderators of political inequality

It is well known that socioeconomic characteristics such as education or income can and often influence political participation, with citizens holding higher levels of cognitive and economic resources participating more (Brady, Verba and Schlozman, Reference Brady, Verba and Schlozman1995; Teorell, Sum and Tobiasen, Reference Teorell, Sum and Tobiasen2007; Gallego, Reference Gallego2008). Socioeconomic characteristics thus condition the extent to which different individuals are fully included in the political system. Populism has been interpreted precisely as a reaction against the failure of democratic political systems to guarantee democratic inclusiveness (Mény and Surel, Reference Mény and Surel2002). Hence, populism is expected to appeal particularly to the marginalized and excluded, as one of populism’s core ideas is to bring ‘the average person’ into the political arena (Canovan, Reference Canovan1999). Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser note, consequently, that one of the potentially corrective consequences of populism is that it can mobilize excluded sections of society and give voice to groups that do not feel represented by the elites (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012a, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017).

Previous research has looked at how the presence of populist parties may affect turnout either directly (Huber and Ruth, Reference Huber and Ruth2017) or through the reaction they generate (Immerzeel and Pickup, Reference Immerzeel and Pickup2015), but to the best of our knowledge, the individual-level mechanism that would account for these behavioural consequences of populism has not yet been addressed.

The argument that sustains our expectation that people with low levels of education or income should be more affected by populist motivations is twofold. First, citizens with low levels of education and, particularly, income, are more likely to identify themselves as ‘the people’ – as we have seen, a central component of populism. Although ‘the people’ is an empty signifier and, as such, has different meanings in different contexts, low-income citizens are generally more likely to consider themselves ‘the common people’, while wealthier citizens are not, and ultimately, they can only sympathize with ‘the people’. Hence, we expect citizens with fewer resources to be more likely to experience identity-based motivations to participate around the idea of a homogeneous people comprised of ‘ordinary men’ as opposed to the rich, educated elite (Aslanidis, Reference Aslanidis2016).

Second, people with lower levels of resources may also be more attracted to and mobilized by the more simplistic messages conveyed by populist rhetoric (Bischof and Senninger, Reference Bischof and Senninger2018). Previous research has found that anti-elite rhetoric simplifies decisions and stimulates engagement among low-income voters, closing the internal efficacy gap between poor and rich voters (Marx and Nguyen, Reference Marx and Nguyen2018). At the individual level, holding populist attitudes can similarly compensate for some of the consequences of having lower levels of resources by helping to make sense of politics and participation.

Thus, we expect populist attitudes to modulate how socioeconomic characteristics affect political participation by offering motivations that may resonate particularly with disadvantaged individuals: the less-educated and those with lower income. Education and, especially, income are the two variables that better represent socioeconomic disadvantages and are typically included in all resource models of political participation to gauge political inequality (Verba and Nie, Reference Verba and Nie1972; Parry, Moyser and Day, Reference Parry, Moyser and Day1992; Brady, Verba and Schlozman, Reference Brady, Verba and Schlozman1995; Gallego, Reference Gallego2008). The estimated effect of having populist attitudes (vs. not having them) on participation is expected to be greater for individuals in disadvantaged positions regarding these socioeconomic variables. Consequently, we expect populist attitudes to reduce the effects of education and income on political participation by motivating especially less-educated and impoverished individuals (Hypothesis 2).

Data and measurement

To test the posited hypotheses, we draw on an online survey conducted jointly in June of 2015 in nine European countries (France, Italy, Germany, Greece, Poland, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and UK) that provide a sample of different contexts where our hypotheses can be tested. The samples, recruited by YouGov using the methodologies available in each country, are quota balanced in order to match national population statistics in terms of sex, age, and education level. This cross-country study allows us to examine political engagement as a function of individuals’ socioeconomic characteristics and their populist attitudes, and the interaction between the two. Variables of interest are coded to run from 0 to 1 (except age) and are operationalized as follows.

Political participation. As dependent variables, we use indicators of participation in demonstrations, petition signing, and online political expression in the past 12 months, as well as reported turnout in the last general election in the respondent’s country. These are the most frequently engaged in modes of participation included in the survey for which we expect populism to matter.Footnote 1

Populist attitudes. We use the six-item measure proposed by Akkerman et al., developed as a result of previous efforts by Hawkins and colleagues (Hawkins and Riding, Reference Hawkins and Riding2010; Hawkins, Riding and Mudde, Reference Hawkins, Riding and Mudde2012; Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove, Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014). The six statements, displayed in the Appendix, are designed to tap the core ideas that make up the populist discourse, namely, people-centrism, anti-elitism, antagonism between the people and the elite, and the primacy of popular sovereignty. Respondents’ agreement with each of the statements was measured using a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.Footnote 2 The internal consistency of the resulting composite scales (mean of scores) is good for the whole sample, with an internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of 0.83, and across all countries in the survey, with alphas varying between 0.77 (Greece) and 0.87 (France).

Education. Measured in nine levels (following a standardized coding scheme from primary education to PhD).

Income. Measured in deciles based on the respondent’s country distribution adjusted for size of household using the OECD-modified equivalence score.

Controls. We control for the effect of gender (female), age (coded in years), interest in politics (a 4-point scale ranging from not at all interested to very interested), ideology (an 11-point scale from extreme left to extreme right), ideology squared (to identify the potential effect of radicalism), closeness to a party (not close to any party, somewhat close to a party, quite close to a party, very close to a party), and internal efficacy (a composite index based on the average value of three different items, as reported in the Appendix). The supplementary materials (available online) also include models with additional controls (political trust, external political efficacy, anger, and authoritarian values).

Our empirical strategy comprises two steps. First, we estimate the effect of populist attitudes on each of the participation measures (with controls). This allows testing for Hypothesis 1 (populist attitudes are positively related to political participation). Second, we introduce an interaction term between populist attitudes and education and income, in turn, to test Hypothesis 2 (populist attitudes reduce the effects of income and education on political participation).

Since the dependent variables are dichotomous, we use logistic regression. The models are first run on the pooled data set, using country-level fixed effects and robust standard errors clustered by country. All models are then replicated on each of the country samples separately in order to explore national differences. The Appendix includes detailed question wordings, descriptive statistics for all variables (Table A1) and pooled data models (tables A2 to A4). The detailed results of the country estimations and additional analyses are contained in the online supplementary materials.

Results

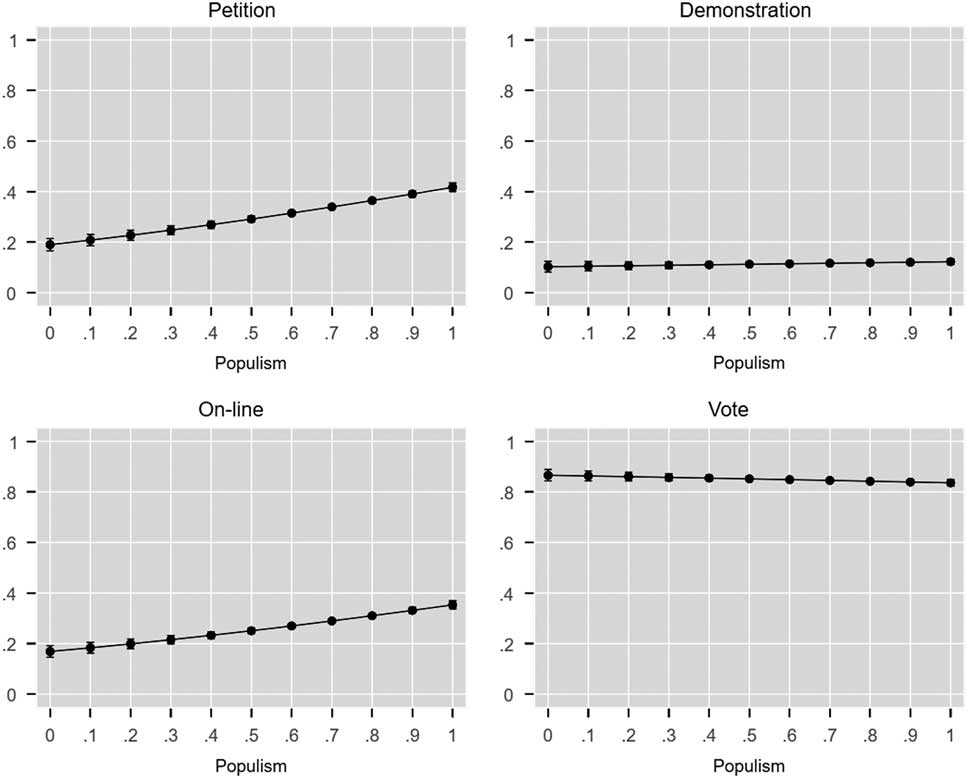

We first estimate the effects of populist attitudes on the likelihood of participating in the four different modes considered, controlling for sociodemographic characteristics and political attitudes that may be correlated with populist attitudes and participation. To facilitate interpretation, Figure 1 plots the relationship between populist attitudes and each of the political participation modes (predicted values are calculated holding all other variables at their observed values; estimates are shown in Table A2 of the Appendix). Populist attitudes have a positive and significant effect on petition signing and online participation. Going from the minimum to the maximum level of populism increases the probability of participating in petition signing from 0.19 to 0.42. People with low levels of populist attitudes have a probability of expressing their views online of 0.17, which increases to 0.36 when populism is at its maximum. These are large and significant effects. We find a modest and not statistically significant effect of populism on the probability of demonstrating (from 0.10 to 0.12). Finally, we find a small negative and not significant effect of populist attitudes on turnout.

Figure 1 Predicted probabilities of participating in different modes of political activity by level of populist attitudes (all other variables at their observed values), as estimated in Table A2.

As summarized in Table 1, the analyses by country confirm the overall sample analysis for petitions, online participation and voter turnout (full models are reported in the online supplementary materials). In all countries, populism is positively related to petition and online expression. The effect is statistically significant at conventional levels in most countries, but effects tend to be smaller and not statistically significant in Germany, Poland, and Sweden. There is an unexpected negative effect of populism on electoral turnout in Germany, Poland, and Switzerland, where high levels of populist attitudes actually demobilize citizens by reducing the probability of voting in a general election. In all other countries, turnout does not seem to be affected by the degree of populist attitudes.

Table 1 Summary of the impact of populist attitudes on political participation by country

Entries are logistic regression coefficients (standard errors in parentheses) taken from the models included in the online supplementary materials (controlling by gender, age, education, income, interest in politics, ideology, ideology squared, closeness to a party, and internal efficacy).

* p < 0.1.

** p < 0.05.

*** p < 0.01.

The country models also offer a more mixed picture of the relationship between populist attitudes and demonstrating, which was positive but not statistically significant for the overall sample. In fact, the relationship between populism and demonstrating varies depending on context. In Spain, for instance, going from the minimum to the maximum level of populist attitudes increases the probability of demonstrating from 0.08 to 0.21, whereas in Greece it changes from 0.06 to 0.30. However, in Switzerland, the relationship between populist attitudes and the likelihood of demonstrating is negative.

Hypothesis 1, thus, seems to find strong support in our data as far as petition and online expression are concerned, both in the pooled and in the country analyses. For demonstrating, the relationship holds in some cases, but it is opposite to what is expected in others. Hypothesis 1 is disconfirmed for turnout: in most countries, there is no significant relationship between populist attitudes and turnout. Where it is significant, the relationship is negative. To summarize, populist attitudes do not motivate citizens to turn out more, but they increase the likelihood of petition signing, online political expression and, in some cases, demonstrating.

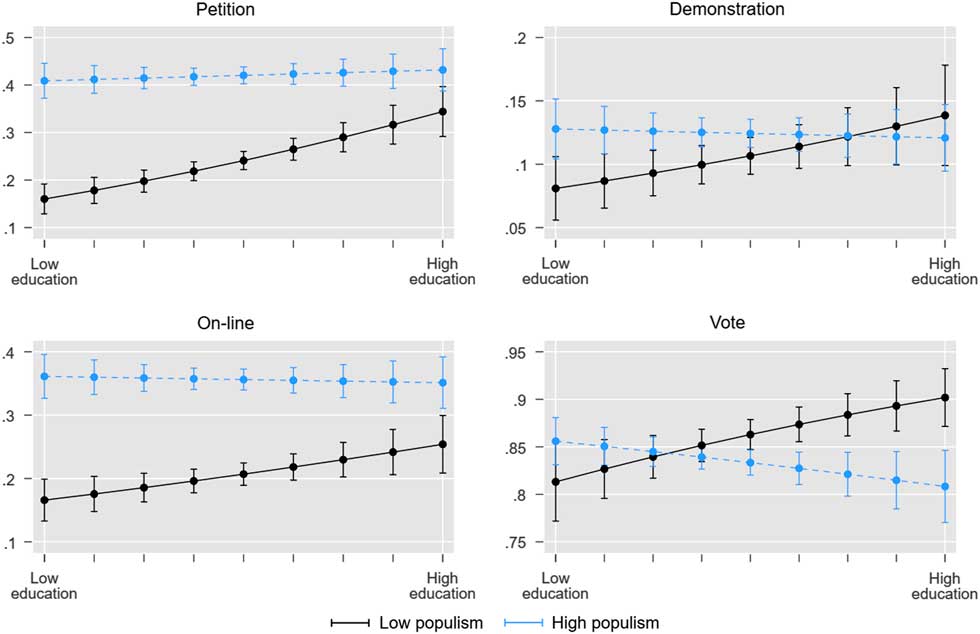

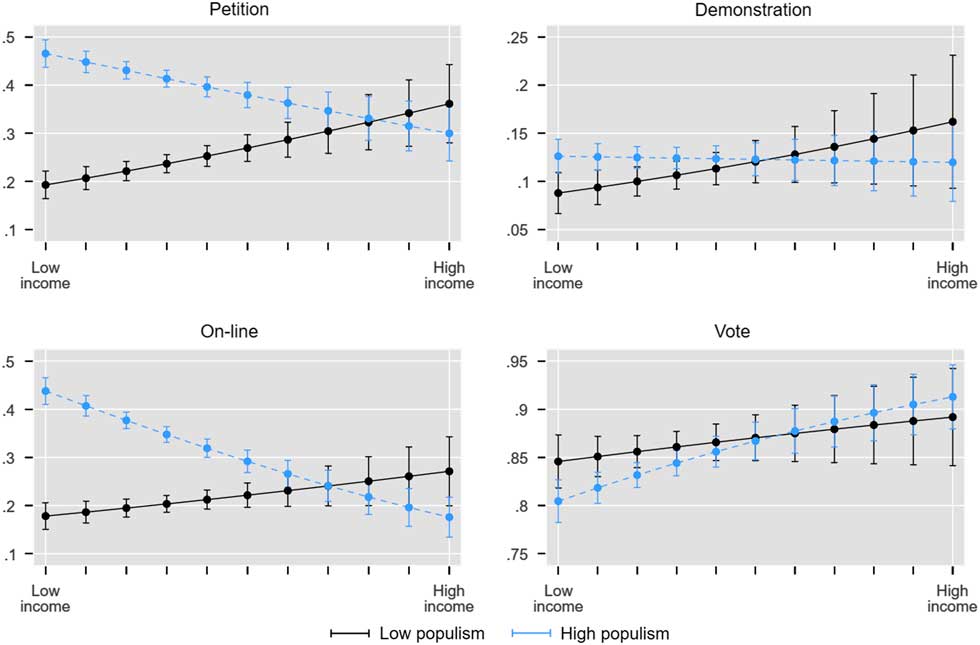

Turning to Hypothesis 2, we add interaction terms between populist attitudes, on the one hand, and education and income, on the other hand. Figures 2 and 3 plot the effects of education and income, respectively, on the probability of participating, distinguishing between citizens scoring low and high on populism. Because the scale of populist attitudes is negatively skewed (people tend to show high levels of populist attitudes), we set a low level of populism at 0.25 (less than 1% of our sample is below 0.25) and a high level at 1 (where the highest 6% of the distribution is located). The slope of the lines can be interpreted as the magnitude of the education-based and income-based gaps in participation: the steeper the line, the larger the difference in expected participation between those with low and high levels of cognitive and economic resources. The complete models are shown in Tables A3 and A4 of the Appendix (for the whole sample) and in the online supplementary materials (for each country).

Figure 2 Predicted probabilities of participating in different modes of political activity by level of education, for low (0.25) and high (1) levels of populism (all other variables at their observed values), as estimated in Table A3.

Figure 3 Predicted probabilities of participating in different modes of political activity by household income, for low (0.25) and high (1) levels of populism (all other variables at their observed values), as estimated in Table A4.

The results for education (Figure 2) show that, to a large extent, populism corrects inequalities in participation: the line representing individuals with high levels of populism is considerably flatter than the line for non-populist individuals, for all four modes, thereby reflecting that education has only a small or no effect on the probability of participating for people with high levels of populist attitudes. This is the logical consequence of the fact that populism has a larger (positive) effect on the probability of demonstrating, signing petitions and expressing political views online for people with low levels of education than for the highly educated.

The effect is very small and not statistically significant for demonstrating, but it is substantial for petition signing and online expression. Populism increases the probability of signing petitions by about 25 percentage points for those with low levels of education (from 0.16 to 0.41) but only 9 points for the highly educated (from 0.34 to 0.43), hence closing the education-based gap in this mode of participation. Likewise, populism increases the probability of online political expression by about 20 points for those with low levels of education (from 0.17 to 0.36), while the change is half the size for the highly educated (from 0.25 to 0.35).

For turnout, there is also a compensatory effect but in this case it results mainly from the demobilization of highly educated people: while populist attitudes do not significantly increase the turnout of individuals with low levels of education, they result in people with higher education being less likely to vote (from 0.90 to 0.81).

Even larger compensatory effects of populist attitudes are found in relation to income, as displayed in Figure 3. Populist attitudes increase levels of engagement of impoverished people in all modes except for turnout, while they do not change the probabilities of participating for the wealthy. Having populist attitudes increases the probability of signing a petition or engaging in online expression by more than 25 percentage points for individuals with low income (from 0.19 to 0.47 for signing a petition and from 0.18 to 0.44 for engaging in online expression, respectively). The increase is more modest for demonstrating but still substantial (4 percentage points) and statistically significant. By contrast, for high-income people, the probabilities of participating are not significantly altered by the presence of populist attitudes.

As a consequence, income gaps in participation are not only reduced significantly by populist attitudes but may even be reversed. It appears that both petition signing and online participation are particularly attractive options for low-income individuals with high levels of populist attitudes. Populist attitudes reduce education-based gaps for all modes and reverse income gaps in participation for non-institutional modes of participation, thus providing support for the expectations derived from Hypothesis 2.

Discussion

Our evidence suggests that populist attitudes can be an important motivating factor for becoming more politically engaged in non-institutional expressive modes of participation such as petition signing (mostly done online) and the online expression of political opinions. While it may seem that the relevance of these two modes is smaller than that of others, research shows that, typically, online participation is positively related to and precedes other offline modes of political engagement (Conroy, Feezell and Guerrero, Reference Conroy, Feezell and Guerrero2012; Gil de Zúñiga, Jung and Valenzuela, Reference Gil de Zúñiga, Jung and Valenzuela2012; Vissers and Stolle, Reference Vissers and Stolle2014; Kim, Russo and Amna, Reference Kim, Russo and Amna2017). Online participation can thus be a stepping stone for additional engagement. Moreover, political messages on social-networking sites have effects on actual political behaviour such as voting (Bond et al., Reference Bond, Fariss, Jones, Kramer, Marlow, Settle and Fowler2012), highlighting the relevance of online political participation.

Different reasons may account for the fact that online expressive participation and petition signing are particularly reactive to populism as a motivation. One of these may be that these modes of action do not require the intermediation of any institution, which is one of the aspects with which populism is unhappy. They are also modes that allow for a larger space than others to express the moral outrage that is associated with populist attitudes without requiring a specific, highly organized call for action. In addition, they are modes of participation that require little time, money or effort; the effect of populism as a motivating factor seems to make a larger difference in participation for these low-cost modes.

An argument could be made that being politically active online makes people more likely to be exposed to populist discourses and, hence, to develop populist attitudes. Previous works have highlighted how social media activism reflects some rhetorical features of populism: typical populist claims and terms (the common man, unity, direct democracy), match typical social media concepts (the Internet user, interactivity, openness, directness or democracy 2.0) (Gerbaudo, Reference Gerbaudo2013). Some works suggest that online platforms contribute to presenting their ideology and worldview, representing ‘the people’, constructing threats, or enhancing confirmation bias through selective exposure (Krämer, Reference Krämer2017). If this is the case for populist parties more than for mainstream ones, then we could expect that online activism may, in turn, enhance populist attitudes. Alternative research designs should address this question in future works. Further research should also explore in depth the mechanisms behind the relationship between populist attitudes and participation: How do identity, purpose, emotions, and morality mediate the relationship between populism and participation? Is this motivating role of populism dependent more on the positive component of the people-centrism of populism (identity) or is it due, rather, to its negative anti-elitism (moral outrage)?

Populist attitudes, by contrast, do not motivate people to turn out more for elections. In three countries, populism even significantly reduces the probability of voting, but for most cases our findings confirm previous works at the aggregate level that have found no relationship between voter turnout and populism. These works look at the presence of a populist head of government (Huber and Ruth, Reference Huber and Ruth2017), populist discourses (Allred, Hawkins and Ruth, Reference Allred, Hawkins and Ruth2015), populist candidates (Houle and Kenny, Reference Houle and Kenny2014), or anti-elite rhetoric (Marx and Nguyen, Reference Marx and Nguyen2018). There may be measurement issues behind this null finding (as turnout is severely over-reported in surveys). But in our view, this lack of a positive effect regarding voter turnout may be due to the same argument that explains stronger effects for expressive non-institutional modes: populist discourses are not particularly at ease with the ‘ossified’ institutional channels such as elections, and consider modes that are direct and spontaneous more attractive. Interestingly, high levels of populist attitudes reduce the probability of voting by citizens with higher levels of education, but not their probability of participating through other modes. This suggests that these more-educated populist citizens (but not wealthy populists) may have interiorized the more-sophisticated idea that institutional channels of participation are not the best tool for conveying the people’s will and that they would prefer unmediated channels. Among sophisticated citizens, populist attitudes seem to motivate some degree of voter abstention.

Countries also present different patterns of association between populist attitudes and demonstrating, with some negative and some positive relationships, which seem to depend on the characteristics of the political supply. Demonstrations require some articulation and organization from political actors. Having left-wing populist actors providing a supply of political protests via demonstrations seems to be the situation in which a positive association between populist attitudes and demonstrating develops (e.g. Spain, Greece), but the overall number of demonstrations could be a relevant factor too, as the case of France suggests. On the other hand, in countries where demonstrations are staged by organizations opposed to populist actors (e.g. trade unions in Sweden) or when a populist party is in power (e.g. Poland and Switzerland), the opposite relationship may develop. Our small sample of countries does not allow us to disentangle the relevant contextual factors explaining cross-national differences in these effects, and thus, further research should also seek to systematize the conditions under which populist attitudes have a positive or a negative effect on the likelihood of demonstrating and electoral turnout.

Finally, and probably most importantly, the presence of populist attitudes has an effect that is conditional on levels of education and income, and hence a capacity to impact on inequality in political participation. Populist attitudes reduce education-based gaps in political participation. The balancing conditional effect is even larger for income: populist attitudes concentrate all their mobilization potential in low-income individuals. The larger capacity of populist attitudes to enhance participation for low-income individuals may be explained by the fact that, as noted by Hakhverdian et al. (Reference Hakhverdian, Van Der Brug and De Vries2012), no group tends to identify with educational categories, nor do parties usually stand as representatives of their interests. Populism seems to resonate much more among the economically deprived (see for instance ‘the 99%’, a category based on income). This does not need to prevent other non-economic grievances from playing a relevant role (Gest, Reference Gest2016), as socioeconomic status is typically combined with cultural elements (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017, p. 10).

These findings provide empirical evidence for the claim that populism can have some corrective effects for democracy, such as ‘giving voice to groups that do not feel represented by the political elite’ (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017: 83) or, we claim, to disadvantaged groups with low education or income. While this is a finding that may lead to some optimism, given the extent of populism and how unequal participation remains, it must be interpreted with care. We are looking at populism as an individual political attitude, net of other attitudes and values that may give different colours to subsequent political engagement. The content and purpose of such engagement may be very different depending on what the political correlates of populist attitudes are.

Acknowledgments

Results presented in this article have been obtained within the project ‘Living with Hard Times: How Citizens React to Economic Crises and Their Social and Political Consequences’ (LIVEWHAT). This project is funded by the European Commission under the 7th Framework Programme (grant agreement no. 613237). The authors are very grateful to the EPSR editors and anonymous reviewers for their useful comments.

Supplementary materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773918000243

Appendix

Variable coding

Education

‘What is the highest level of education that you have completed? If your qualification is not listed, please select the level that most closely resembles your highest classification’. Coded using a standardized 9-level scheme running from primary education or less to doctoral degree or equivalent.

Household income

‘What is your household’s MONTHLY income, after tax and compulsory deductions, from all sources? If you do not know the exact figure, please give your best estimate’. Coded in deciles of the income distribution in the given country, and adjusted for the size of the household using the OECD-modified equivalence scale.

Populist attitudes

‘To what extent do you agree or disagree with each of the following statements?’

1. The politicians in [country] need to follow the will of the people

2. The people, and not politicians, should make our most important policy decisions

3. The political differences between the elite and the people are larger than the differences among the people

4. I would rather be represented by a citizen than by a specialized politician

5. Elected officials talk too much and take too little action

6. What people call ‘compromise’ in politics is really just selling out on one’s principles

Each item is measured on a five-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The composite index is the average score across all items and scores between 0 and 1.

Interest in politics

‘How interested, if at all, would you say you are in politics?’ Not at all interested, not very interested, quite interested, very interested.

Ideology

‘People sometimes talk about the Left and the Right in politics. Where would you place yourself on the following scale where 0 means ‘Left’ and 10 means ‘Right’?’

Closeness to a party

‘Which of the following parties do you feel closest to?’

‘How close do you feel to [Party name]’ Somewhat close, quite close, very close.

Internal efficacy

‘To what extent do you agree or disagree with each of the following statements?’

1. I consider myself well-qualified to participate in politics

2. I feel that I have a pretty good understanding of the important political issues facing our country

3. I think that I am as well-informed about politics and government as most people

Each item is measured on a five-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The composite index is the average score across all items and scores between 0 and 1.

Voter turnout

‘Some people don’t vote nowadays for one reason or another. Did you vote in the previous (year) national election?’ 1 means voted and 0 did not vote.

Petition, demonstration, online expressive participation

‘There are different ways of trying to improve things or help prevent things from going wrong. When have you LAST done the following?’

1. Signed a petition/public letter/campaign appeal (online or offline)

2. Attended a demonstration, march, or rally

3. Discussed or shared opinion on politics on a social network site, for example Facebook or Twitter

All modes are dummy variables scoring 1 if the respondent answered ‘In the past 12 months’ and 0 otherwise to the following question:

Table A1 Summary statistics

Table A2 The relationship between populist attitudes and political participation, pooled sample

Table A3 The interaction between populism and education, pooled sample

Table A4 The interaction between populism and income, pooled sample