Introduction

The 1959 Mental Health Act represented, by any standard, a ‘paradigm shift’ in the way in which mental illness was construed, not just in Britain but anywhere.

Its predecessor was the Lunacy Act of 1890. Kathleen Jones, in her influential History of the Mental Health Services characterised that Act thus:

The Act itself is an extremely long and intricate document, which expresses few general principles and provides detail for almost every known contingency. Nothing was left to chance, and very little to future development.

…

From the legal point of view it was nearly perfect … From the medical and social viewpoint, it was to hamper the progress of the mental-health movement for nearly 70 years.1

Laws governing detention and treatment in the nineteenth century were developed in the setting of the expanding asylum system. The early enthusiasm for ‘moral treatment’ failed to live up to its promise. The numbers of those detained in the asylums grew far beyond what was originally envisaged.

Under the Lunacy Act 1890 admission to an asylum or licensed house depended on whether the case was private (involving a justice of the peace and two medical certificates) or pauper (involving a Poor Law receiving officer or the police, a medical certificate and a justice of the peace).2

Admission by inquisition, whose origins dated back to the fourteenth century applied to so-called Chancery lunatics – expensive and affordable only to those with large estates and great wealth. The alleged lunatic could request a trial of their sanity by jury.

There were detailed regimes of visitation by Lunacy Commissioners – unannounced, at an hour, day or night. A report book for instances of mechanical restraint was kept; a medical certificate was necessary for each instance.

Discharge arrangements were complex and could differ for private versus pauper patients. They might involve the person signing the petition for the reception, the authority responsible for the maintenance of the pauper patient, two Lunacy Commissioners – one legal and one medical – or three members of the visiting Local Authority committee.

The Mental Treatment Act 1930 followed a Royal Commission on Lunacy and Mental Disorder 1924–6.3 It proposed that mental illness should be viewed like any other illness, and its recommendation that treatment should not necessarily be contingent upon certification was accepted. The Lunacy Act was amended but earlier legislation was not replaced. The Act introduced ‘voluntary admission’ by written application to the person in charge of the hospital. Non-objecting but non-volitional patients, called ‘temporary’, could be admitted under a non-judicial certificate. An essential condition in the application for reception of a ‘temporary’ patient was that the person ‘is for the time being incapable of expressing (him)(her)self as willing or unwilling to receive such treatment’.4 For many clinicians, the meaning of this provision lacked clarity, accounting for a huge variation in its use – from 34 per cent to 0 per cent.5

Magistrates continued to be involved in overseeing compulsory hospital admissions. The Act authorised local authorities to set up psychiatric outpatient clinics in general and mental hospitals, but the hospital remained the focal point for psychiatric provision.

The Mental Health Act 1959

The Mental Health Act 1959 followed the key recommendation of the Percy Royal Commission, established in 1954, ‘that the law should be altered so that whenever possible suitable care may be provided for mentally disordered patients with no more restriction of liberty or legal formality than is applied to people who need care because of other types of illness’.6

The Act repealed all previous legislation.7 Informal admission was now the usual method of admission. For the first time since 1774, there was no judicial authorisation for a compulsory admission. Patients could be admitted to any hospital or mental nursing home without any formalities. This replaced the ‘voluntary admission’ set down in the Mental Treatment Act of 1930 where the patient signed admission papers. Non-volitional patients could be admitted informally provided that they did not positively object to treatment.

Mental disorder was defined as ‘mental illness; or, arrested or incomplete development of mind (i.e. subnormality or severe subnormality); or, psychopathic disorder; or any other disorder or disability of mind’.

Psychopathic disorder was defined as a persistent disorder resulting in abnormally aggressive or seriously irresponsible conduct and susceptible to medical treatment. Persons were not to be regarded as suffering from a form of mental disorder by reason only of promiscuity or immoral conduct.

There were three kinds of compulsory admission:

Observation order: up to twenty-eight days’ duration, made on the written recommendations of two medical practitioners stating that the patient either (1) is suffering from a mental disorder of a nature or degree which warrants his (sic) detention under observation for a limited period or (2) that he ought to be detained in the interests of his own health and safety, or with a view to the protection of other persons.

Treatment order: for up to a year, to be signed by two medical practitioners. The grounds were:

(a) The patient must be suffering from mental illness or severe subnormality; or from subnormality or psychopathic disorder if he is under the age of twenty-one.

(b) He must suffer from this disorder to an extent which, in the minds of the recommending doctors, warrants detention in hospital for medical treatment; and his detention must be necessary in the interests of his health and safety, or for the protection of other persons.

Emergency order: following an application made by the mental welfare officer or a relative of the patient and backed by one medical recommendation. The patient had to be discharged after three days unless a further medical recommendation had been given satisfying the conditions of a treatment order.

A Mental Health Review Tribunal (MHRT) alone took over the previous watchdog functions of the Lunacy Commission (which had later become the Board of Control). Detention could be reviewed at the request of patients or relatives or at the request of the minister of health. The tribunal consisted of an unspecified number of persons: legal members appointed by the Lord Chancellor; medical members appointed by the Lord Chancellor in consultation with the minister; lay members having such experience or knowledge considered suitable by the Lord Chancellor in consultation with the minister.

A patient was discharged by the Responsible Medical Officer (RMO), by the managers of the hospital, by an MHRT, by the patient’s nearest relative – though with a possible RMO veto – or, in the case of subnormality or psychopathy, if the person had reached the age of twenty-five.

Guardianship, which had its origins in mental deficiency legislation and promised a degree of control in the community, could now be applied to those with a mental disorder.

Space does not allow us to discuss provisions for mentally disordered offenders in detail. In brief, courts could order admission to a specified hospital or guardianship for patients with a mental disorder of any kind, founded on two medical recommendations. Courts of Assize and Quarter Sessions could place special restrictions on the discharge of such patients. Power to grant leave of absence, to transfer the patient to another hospital or to cancel any restrictions placed on their discharge was reserved to the Home Secretary. Limitations were placed on the appeal of such patients to an MHRT. Those found ‘Not guilty by Reason of Insanity’ were detained during ‘her Majesty’s pleasure’ by warrant from the Home Secretary. The Mental Health Act 1959 provisions by and large resemble those of today, with a significant change concerning the power of the MHRT in 1982, discussed later. The medical profession was united in its enthusiasm for the new provisions and the status of psychiatrists in the medical sphere was enhanced.

The Context of This Radical Change in Mental Health Law

A new optimism had emerged concerning the effectiveness of psychiatric treatment, with a new expectation that patients would return to their communities following a short admission. Jones talked in terms of ‘three revolutions’: pharmacological, administrative and legal.8

The ‘Pharmacological Revolution’

The standing of psychiatry as a medical speciality, based on scientific principles, was boosted with the introduction in the early 1950s of the antipsychotic drug chlorpromazine. Admissions had become shorter and much more likely to be voluntary. The antidepressants, imipramine and iproniazid, were introduced later in the decade. New psychosocial interventions, such as the ‘therapeutic community’ and ‘milieu therapy’ looked promising. There was a sense of a ‘therapeutic revolution’.

The ‘Administrative Revolution’

A 1953 World Health Organization (WHO) report (Third Report: The Community Mental Hospital) described new models for mental health services. Combinations of a variety of services were proposed, including ‘open door’ inpatient units, outpatients, day care, domiciliary care and hostels. Earlier treatment, it claimed, meant fewer admissions; chronic patients could be satisfactorily cared for at home or boarded out. The report significantly influenced the Royal Commission’s determinations.

There were other administrative considerations. In 1948, the new National Health Service (NHS) found itself responsible for the management of 100 asylums, each with its own regulations and practices. Their average population was around 1,500 patients. Patients with a ‘mental illness or mental deficiency’ occupied around 40 per cent of all hospital beds.9

The ‘Legal Revolution’

Some legal matters were complicated by amendments introduced by the National Health Service (NHS) Act 1946. There was also a welfare state–influenced reimagining of law of this kind, now to be seen as an ‘enabling’ instrument as opposed to a coercive or constraining one.

Tackling the stigma of mental illness was another theme. There was agreement that stigma was heightened by what was called the ‘heaviness of procedure’ manifest in the magistrate’s order, linking in the public’s mind the deprivation of liberty for the purposes of treatment with that for the purposes of punishment.

Unsworth summarised the significance of the 1959 Act as a negation of the assumptions underlying the Lunacy Act:

The [1959] act injected into mental health law a contrary set of assumptions drawing upon the logic of the view of insanity as analogous to physical disease and upon reorientation from the Victorian institution-centred system to ‘community care’. … Expert discretion … was allowed much freer rein at the expense of formal mechanisms incorporating legal and lay control of decision-making procedures.10

A ‘pendulum’ thus had swung through almost its full trajectory, from what Fennell and others have termed ‘legalism’ to ‘medicalism’,11 a form of paternalism.

A warning was sounded in parliament, however, by Baroness Wootton:

Perhaps there is a tendency to endow the medical man with some of the attributes that are elsewhere supposed to inhere in the medicine man. The temptation to exalt the medical profession is entirely intelligible … but I think it does sometimes place doctors in an invidious position, and sometimes possibly lays them open to the exercise of powers which the public would regard as arbitrary in other connections.12

Mental Health Act 1983

Twenty-four years later, a new Mental Health Act was passed.13 While the general outline of the 1959 Act was preserved, there was a significant swing of the ‘pendulum’ towards a new form of ‘legalism’.

Among the changes introduced in the 1983 Act, the following were notable:

1. For the first time, the idea of consent to treatment, even if the patient was detained, made its appearance in mental health law. A requirement for consent was introduced for certain hazardous or irreversible treatments – psychosurgery and surgically implanted hormones. These now required the patient’s consent and approval by a panel of three people, including a psychiatrist, appointed by the Mental Health Act Commission (see item 4). Further, consultation with two persons professionally involved with the treatment (other than the patient’s consultant) was needed. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and the administration of medications for the mental disorder beyond three months required consent or a second opinion if the person could not or did not consent.

2. An expanded role and enhanced training was introduced for ‘approved social workers’ in respect of a social assessment.

3. Access to review of detention by the MHRT was expanded and now included patients under a 28-day ‘assessment’ order and automatic review with renewal of a treatment order. Patients became entitled to publicly funded legal representation.

4. An oversight body concerning detained patients, the Mental Health Act Commission, was established. It will be recalled that there was no such body under the 1959 Mental Health Act.

5. Patients suffering from ‘psychopathic disorder’ or ‘mental impairment’ could only be detained if their behaviour was ‘abnormally aggressive or seriously irresponsible’ and if treatment was likely to alleviate or prevent a deterioration of their condition (i.e. a ‘treatability’ criterion’).

6. A duty was placed on the District Health Authorities and local social services authorities to provide aftercare services for patients admitted on a treatment order or on some forensic orders.

In these domains, the rights of persons with a mental disorder were thus enhanced.

What Was the Context of These Changes?

In an extended history of mental health services, Jones began her analysis of the post-1959 period thus:

After the passing of the 1959 Act, it would have been reasonable to expect a period of consolidation and cautious experimentation; but within two years, the whole scene changed. In 1961, a new Minister of Health, Enoch Powell, announced a policy of abolishing mental hospitals, and cutting psychiatric beds by half … Opposition to this draconian policy was muted by three new theoretical analyses … opposed to mental hospitals for very different reasons.14

She was referring to Szasz, Goffman and Foucault. We shall come to them later in this section (see also Chapter 20).

The Ministry of Health’s A Hospital Plan for England and Wales followed Powell’s ‘Water Tower speech’. It proposed the restriction of hospital care mainly to the acute sector. Under a ‘parity of esteem’, this applied to psychiatry just as it did to the rest of medicine. Thus commenced a huge reduction in the number of hospital beds. At the same time, the Department of Health faced increasing fiscal pressures arising from the need to refurbish and maintain decaying public hospitals. The forces leading to the policy of deinstitutionalisation here overlapped with those acting to reduce admissions, including recourse to involuntary hospitalisation. Some noted an ‘unnatural alliance’ between civil rights advocates on the left, who distrusted the state and psychiatric expertise, and monetarist conservatives, who were concerned with the high institutional costs of mental health care (see also Chapter 31).

Highly publicised scandals involving mental hospitals continued – there were some twenty serious inquiries into maltreatment between 1959 and 1983. Faith in the effectiveness of medication – and in pharmaceutical companies, especially following the thalidomide inquiry – was faltering.

Proposals from some academic authorities that outcomes would improve if treatment were focused in the community rather than in hospitals were welcome to government. Evidence was offered that ‘total institutions’ like mental hospitals, in which almost every aspect of the resident’s life is subservient to the institution’s rules, far from being therapeutic, in fact contribute to a dehumanising erosion of personal identity, dependency and disability. Here Goffman’s 1961 Asylums and Barton’s 1959 Institutional Neurosis were influential.15

Joined to these criticisms was another set of voices denying the legitimacy of the psychiatric enterprise itself. Key figures in this loosely termed ‘anti-psychiatry’ movement included three psychiatrists – Thomas Szasz, R. D. Laing and David Cooper (see also Chapter 20). Szasz held that ‘mental illness’ was a ‘myth’ and had no kinship with ‘real’ illness; so-called mental illnesses were ‘problems of living’, not brain diseases.16 From a rather different perspective, Laing and Cooper argued that insanity was an understandable reaction of some to impossible family pressures or, indeed, a society gone insane.17 The experience of psychosis, they claimed, handled correctly – as opposed to conventional treatment – could be transformative.

In significant ways congruent with the ‘anti-psychiatry’ movement were the ideas of Michel Foucault. His Histoire de la folie, published in 1961, appeared in a much abridged form in English in 1965 (as Madness and Civilization) featuring a polemical introduction by David Cooper.18 Madness and Civilization examined how the notion of ‘mental illness’ assumed the status of ‘positive knowledge’ or objectivity and its irreconcilability with society’s growing valorisation of ‘productive’ citizenship. Foucault argued that psychiatrists’ expertise lay in asylum-based governance and non-medical practices, such as techniques for the normalisation of certain sorts of socially transgressive behaviours.

Thus, while these figures differed significantly in their theories, they had in common a critique of psychiatry’s basic tenets, its social role and the institutions in which these were realised. Their ideas found a place within a broader counterculture movement prominent in the 1960s and 1970s, which helped to bring them to the attention of a wider public.

A further significant influence was the civil rights movement in the United States, increasingly effective in the 1960s and 1970s. Civil rights were progressively asserted for groups subject to discrimination – African Americans, prisoners, women, persons with mental illness and persons with disabilities. An essential instrument was the law; a number of key legal decisions led to changes in institutional practices.

Increasingly publicised abuses of psychiatry in the Soviet Union during the 1970s and early 1980s seemed to point to the fact that, unless involuntary hospitalisation was the subject of special scrutiny, arbitrary detention could follow.

The key player in fostering reform of mental health legislation in the 1970s was the National Association for Mental Health (now Mind). Founded in 1946, it started as a traditional voluntary organisation, a partnership between professionals, relatives and volunteers, aimed at improving services and public understanding. Its character, described by Jones as ‘duchesses and twin-set’, changed in the 1970s (see also Chapter 14).

The organisation was shaken by a serious, though failed, attempt of a Scientology takeover. A ‘consumer’ orientation and a focus on human rights followed, marked by the appointment of Tony Smythe as director in 1974. He was previously secretary-general of the National Council for Civil Liberties (NCCL, later named Liberty). Mind soon established a legal and welfare rights service.

Larry Gostin, co-author of this chapter, an American lawyer and recently a Fulbright Fellow at Oxford, was appointed first legal officer in 1975.19 Both Gostin and Smythe had worked in the domain of civil liberties in the United States. While legal director for Mind, Gostin wrote A Human Condition, essentially Mind’s proposals for reforming the Mental Health Act 1959.20

He stated:

The [1959] Act is largely founded upon the judgment of doctors; legal examination has ceased at the barrier of medical expertise, and the liberty of prospective patients is left exclusively under the control of medical judgments which have often been shown in the literature to lack reliability and validity.21

Gostin challenged the assumption that compulsory detention automatically allowed for compulsory treatment. He proposed that all treatment to be given to an inpatient who cannot, or does not, give consent should be reviewed by an independent body. He argued for the concept of the ‘least restrictive alternative’ (which in turn required the provision of a range of alternative services). He also proposed an extended advocacy system.

Gostin took cases to the courts, ranging from the right to vote and consent to treatment to freedom of communication. A particularly successful example was the 1981 case, X v The United Kingdom, before the European Court of Human Rights, resulting in a new power for MHRTs to discharge restricted forensic patients. While at Mind, he formed a volunteer lawyers panel to represent patients at MHRT hearings.

Gostin subsequently received the Rosemary Delbridge Memorial Award from the National Consumer Council for the person ‘who has most influenced Parliament and government to act for the welfare of society’.

The 1983 Mental Health Act thus marked a swing of the Act’s ‘pendulum’, not especially dramatic, towards ‘legalism’ (or called by Gostin, ‘new legalism’). It differed from Lunacy Act legalism by an accent on the rights of detained patients and their entitlements to mental health care, rather than ensuring that the sane were not mistakenly incarcerated as insane, or the detection of grossly irregular practices.

The newly established Mental Health Act Commission faced a daunting task. In addition to producing a Code of Practice, its oversight function involved up to 728 hospitals and units for mental illness and intellectual disabilities in England and Wales, together with 60 nursing homes which could come under its purview if they housed detained patients.

Mental Health Act 2007: An Amended Mental Health Act 1983

The next Mental Health Act followed thirty-four years later, in 2007.

The reduction in the number of mental health beds continued apace – England saw an 80 per cent reduction between 1959 and 2006. An argument grew in the 1980s that, as the locus of psychiatric treatment was increasingly in the community, so should be the option of involuntary treatment. Early moves in this direction were the ‘long leash’ – the creative use of ‘extended leave’ (ruled unlawful in 1985), the introduction of non-statutory Supervision Registers in 1994 and then the passing of the Mental Health (Patients in the Community) Act in 1995. This introduced Supervised Discharge, also known as ‘aftercare under supervision’. This could require a patient to reside at a specified place and to attend places for medical treatment or training. Administration of treatment could not be forced in the community but the patient could be conveyed to hospital, by force if necessary, for persuasion or admission.

The 1990s saw a new turn – a growing public anxiety that mental health services were failing to control patients, now in the community and no longer apparently safely detained in hospitals, who presented a risk, especially to others (see also Chapter 28). The 1983 Act was labelled obsolete – as, for example, in a highly publicised publication, the Falling Shadow report, following the investigation of a homicide by a mental patient.22

A ‘root and branch’ review of the Mental Health Act 1983 was initiated by the government in 1998. Its purpose, as announced by the then Secretary of State for Health, Frank Dobson, was ‘to ensure that patients who might otherwise be a danger to themselves and others are no longer allowed to refuse to comply with the treatment they need. We will also be changing the law to permit the detention of a small group of people who have not committed a crime but whose untreatable psychiatric disorder makes them dangerous.’

This led to what Rowena Daw, chair of the Mental Health Alliance, a coalition of more than seventy professional organisations and interest groups, called a seven-year ‘tortured history’ of ‘ideological warfare’ between the government and virtually all stakeholder groups.23 The Mental Health Alliance was a unique development. Created in 1999, it incorporated key organisations representing psychiatrists, service users, social workers, nurses, psychologists, lawyers, voluntary associations, charities, religious organisations, research bodies and carers (see also Chapter 28).

Initially, a government-appointed Expert Committee chaired by Professor Genevra Richardson produced generally well-received recommendations founded on the principles of non-discrimination towards people with a mental illness, respect for their autonomy and their right to care and treatment. An impaired ‘decision-making capacity’ criterion was proposed, only to be overridden in cases of a ‘substantial risk of serious harm to the health or safety of the patient or other persons’, and there are ‘positive clinical measures which are likely to prevent a deterioration or to secure an improvement in the patient’s mental condition’.

However, as Daw notes:

Government, on the other hand, had different priorities. It was driven by its wish to give flexibility in delivery of mental health services through compulsory treatment in the community; and its fear of ‘loopholes’ through which otherwise treatable patients might slip. In its general approach, the government followed a populist agenda fuelled by homicide inquiries into the deaths caused by mental health patients. Public concern and media frenzy went hand in hand to demand better public protection. … The then Health Minister Rosie Winterton MP stated that ‘every barrier that is put in the way of getting treatment to people with serious mental health problems puts both patients and public at risk’.24

A ‘torrid passage’ (Daw’s words) of Bills through parliament involved two rejections, in 2002 and 2004, and finally, in 2007, an amending Act to the 1983 Mental Health Act was passed.25

Fanning has detailed the role of the containment of ‘risk’ in the generation of the 2007 Act.26 He notes a swing back from ‘legalism’ to a new form of ‘medicalism’ – or ‘new medicalism’. He explains:

The 1959 Act’s medicalism … trusted mental health practitioners to take decisions for and on behalf of their patients according to clinical need. By contrast, the 2007 Act’s ‘New Medicalism’ expands practitioners’ discretion in order to enhance the mental health service’s responsiveness to risk. This subtle shift in focus introduces a covert political dimension to mental health decision-making … the 2007 Act’s brand of medicalism follows an inverted set of priorities to those pursued in the 1959 Act.27

Fanning examines a link to the characterisation of contemporary society, for example, by Beck and Giddens, as a ‘risk society’ – one preoccupied with anticipating and avoiding potentially catastrophic hazards that are a by-product of technological, scientific and cultural advances (see also Chapters 10 and 17). ‘Risk’ replaces ‘need’ as a core principle of social policy. It also leads to a culture of blame if adverse events should occur. Foucault’s notion of ‘governmentality’ also enters Fanning’s account – risk here offering an acceptable warrant for governmental disciplinary measures.

Another factor was the claim – disputed by a number of authorities – that risk assessment instruments had now achieved an acceptable degree of scientific precision as valid predictors of serious violent acts by persons with a mental disorder. The evidence is that risk assessment instruments for low frequency events, such as a homicide, result in a large preponderance of ‘false positives’ (see also Chapter 10).28

However, there is a problem with ‘risk’, Fanning argues. It is unclear what it really means. He claims:

Within reason, anything practitioners recast as evidence of a threat to the patient’s health or safety or to others is enough to justify the deployment of the compulsory powers … Consequently, it undermines legal certainty and impairs the law’s ability to defend patients’ interests.29

The 2007 Act increased professional discretion on the role of risk by:

simplifying and arguably broadening the definition of ‘mental disorder’;

abolishing the ‘treatability test’ for psychopathy, requiring only that treatment be ‘appropriate’ – previously the treatment had to be ‘likely’ to be effective, now that must be its ‘purpose’;

broadening the range of professionals able to engage the compulsory powers, by replacing the role of the ‘approved social worker’ with an ‘approved mental health professional’, who could be a psychologist, psychiatric nurse or occupational therapist. This reduced the separation of powers that existed between those with clinical and social perspectives; and

introducing Supervised Community Treatment (or Community Treatment Orders, CTOs), effectively strengthening supervision after discharge by the imposition of a broad range of conditions. A failure to comply with the treatment plan may result in recall to hospital; and if treatment cannot be reinstituted successfully within seventy-two hours, the CTO may be revoked with reinstatement of the inpatient compulsory order. The patient may appeal against the CTO but not the conditions.

The reforms represented a substantial shift away from a focus on individual rights and towards public protection. An exception was a strengthening of the need for consent for ECT in a patient with decision-making capacity (except where it is immediately necessary either to save the person’s life or to prevent a serious deterioration of their condition) and a right to advocacy (by an ‘Independent Mental Health Advocate’) for detained patients and those on a CTO.

Fanning goes on to claim that the ‘new medicalism’ maintains a ‘residual legalism’ in the amended Mental Health Act, which:

arguably has a sanitising effect by conferring a veneer of legitimacy on ‘sectioning’ processes which may now be less certain, less predictable and primarily motivated by concern for public safety … Far from being a minor statute which changes very little, the 2007 Act represents an entirely new moment in English mental health law and policy.30

At the same time as deliberations were in progress over reform to the Mental Health Act, parliament was passing the Mental Capacity Act 2005 in which the involuntary treatment of patients in general medicine and surgery was to be based on an entirely different set of principles – ‘decision-making capacity’ and ‘best interests’.

Post-2007 Developments

Two drivers of reform garnered significant support during the first decade of the twenty-first century. The first was the proposal for capacity-based law or a more radical version, known as a ‘fusion law’; the second was the adoption by the United Nations (UN) in 2006 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Both aim at the elimination of unfair discrimination against people with a mental disorder.

A ‘fusion law’ refers to a single, generic law applicable to all persons who have an impairment in the ability to make treatment decisions, whether the cause be a ‘mental disorder’ or a ‘physical disorder’.31 It combines the strengths of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 – that is, a respect for autonomy, self-determination and the right to refuse treatment, almost entirely absent in the Mental Health Act – with the detailed regulation of involuntary detention and treatment – its authorisation, by whom, where, for how long, review and appeal mechanisms, all well specified in conventional mental health legislation but absent from the Mental Capacity Act. Involuntary treatment is restricted to those who lack ‘decision-making capacity’ and where it is in the person’s ‘best interests’. Northern Ireland passed such an Act in 2016 following the path-breaking Bamford Report of 2007.

The UN CRPD presents a huge challenge to conventional psychiatric practice. A number of authorities, including the UN CRPD Committee established by the UN to oversee the convention, holds that any ‘substitute decision-making’ (except perhaps by a proxy appointed by the person with a disability, and who will respect the person’s ‘will and preferences’) is a violation of the CRPD. Thus, treatment against the objection of a patient is prohibited. It remains to be seen how the consequent debate with the many critics of this interpretation will play out.32

Scotland and Northern Ireland

Space permits only a brief account of the salient features of Scotland’s legislation. Until 2003, Scottish mental health law was by and large similar to that of England and Wales (though it did retain in its 1960 Mental Health Act an oversight body – the Mental Welfare Commission and a role in compulsory admissions for a Sheriff). However, the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 marked a substantial departure:

the principle of autonomy is prominent;

it stipulates ten Guiding Principles (with no reference to risk or public safety);

patients must be treatable if compulsion is to be used;

while a criterion of risk to self or others is retained, an additional criterion must be met – a ‘clinically significant impairment of treatment decision-making ability’;

compulsory treatment orders, inpatient or in the community, must be authorised by a Mental Health Tribunal;

there is a right to independent advocacy;

there is a special recognition of advance statements – a failure to respect the person’s wishes needs written justification, which must be reported to the patient, a person named by the patient, a welfare attorney (if there is one) and the Mental Welfare Commission; and

there is a choice of a named person rather than the nearest relative.

Few would deny that this law is far more rights-based than that in England and Wales. As mentioned in the section ‘Post-2007 Developments’, Northern Ireland has taken reform even further, having passed a ‘fusion law’.

European Convention on Human Rights (Human Rights Act 1998)

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to give more than a brief reference to the influence on UK mental health law of the European Convention on Human Rights – later the Human Rights Act (1998). In 2007, Baroness Hale, then a member of the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords, summarised the impact as modest.33 An exception was the ‘Bournewood’ case concerning a man (HL) with autism who was admitted to a hospital as an informal patient, and although he did not, or could not, object, it was apparent that he would not be allowed to leave if he were to wish to do so. His carers, denied access to him, initiated a legal action that he was being detained unlawfully. This progressed with appeals through the English court system up to the House of Lords in 1998, who decided HL’s admission was lawful. His carers then took the case to the European Court of Human Rights, who, in 2004, ruled it was unlawful. This resulted in the Mental Health Act 2007 appending Schedules to the Mental Capacity Act establishing ‘Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards’ covering non-objecting hospital inpatients or care home residents who lacked decision-making capacity and, in their best interests, were not allowed to leave.34

Service User Movement

Similarly, limitations in scope only allow a brief consideration of the influence of service user organisations on changes in mental health law (see also Chapters 13 and 14). Service users had little direct involvement in the development of the 1983 Mental Health Act. While patient groups did form in the 1970s, the service user voice was not significantly heard until the mid-1980s.35 It was reasonably prominent in the debate leading to the 2007 Act, and the major service user organisations joined the Mental Health Alliance. Within or outwith the Alliance, however, their voice was largely ignored by government.

Conclusion

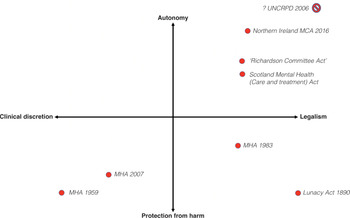

We have traced the course of mental health legislation from 1959 to 2010. The broad sweep of the changes can be summarised schematically, allowing for a degree of simplification. We have adapted the idea from Fanning of locating each law within a space created by two orthogonal dimensions (Figure 8.1).36 While Fanning finally did not support the schema, we propose that by reconceptualising the dimensions, it proves useful. The first dimension has at its poles ‘legalism’ versus ‘clinical discretion’ (or ‘medicalism’). The second has a ‘respect for autonomy’ (or emphasis on decision-making capacity’ and ‘consent to treatment’) versus ‘protection from harm’ (especially to others) dimension. The movements in this ‘legal–clinical–social’ space from the 1890 Act to the 1959 Act, then to the 1983 Act and the 2007 Act can be traced. The Richardson Committee’s 1999 recommendations and the 2003 Scotland Act are also shown, as are the major directions taken in the first decade of the twenty-first century – the Northern Ireland ‘fusion law’ as well as the UN CRPD Committee’s interpretation of the Convention (the claim that ‘substitute decision-making’ is to be abolished means that it is located at the top-right extreme or perhaps falls outside the space altogether).

It is pertinent to ask what has happened to the number of involuntary admissions over the period covered? In England, they declined steadily between 1966 and 1984, rose quite sharply and steadily until 2000 and then remained flat until 2010. The numbers then rose very sharply again (Figure 8.2). The contribution of changes in mental health legislation is difficult to determine. There were increases in involuntary admissions after both the 1983 and the 2007 Acts but other socio-political and administrative changes also occurred. Perhaps the most interesting observation is the stable rate between 2000 and 2008. This period was characterised by a substantial investment in community mental health services, suggesting that resources are a major determinant of the rate of involuntary admissions. Consistent with a resources contribution is the steep rise from 2009, a period of austerity.

Gostin observed that there is perhaps no other body of law which has undergone as many fundamental changes in approach and philosophy as mental health law.37 We have seen that such law reflects shifts – in Jones’s words, ‘good, bad or merely muddled’ – in social responses and values to an enduring and troubling set of human problems.38 We agree with Fennell that, while such laws often may not obviously greatly affect substantive outcomes, they are important, if for no other reason, than they require professionals – and we would add the state and civil society – to reflect on, explain and justify what is being done.39

Key Summary Points

The 1959 Mental Health Act represented, by any standard, a ‘paradigm shift’ in the way in which mental illness was construed, not just in Britain but anywhere. ‘Legalism’ of the 1890 Lunacy Act was replaced by ‘medicalism’.

While the general outline of the 1959 Act was preserved in the 1983 Mental Health Act, there was a significant swing of the ‘pendulum’ towards a new ‘legalism’.

Significant influences were the successes of the civil rights movement in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s that progressively asserted rights for groups subject to discrimination and the establishment of a legal and welfare rights service by the National Association for Mental Health (Mind).

An argument grew in the 1980s that, as the locus of psychiatric treatment was increasingly in the community, so should be the option of involuntary treatment. The Mental Health Act 2007 represented a substantial shift away from a focus on individual rights and towards public protection.

Two drivers of reform garnered significant support during the first decade of the twenty-first century. The first was the proposal for capacity-based law or a more radical version, known as a ‘fusion law’; the second was the adoption by the UN in 2006 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Both aim at the elimination of unfair discrimination against people with a mental disorder.

Changes in mental health law are traced within a space formed by two key dimensions: ‘clinical discretion’ versus ‘legalism and ‘autonomy’ versus ‘protection from harm’.