1. Introduction

When making decisions regarding the early release of a convicted person, the ad hoc tribunals and the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (IRMCT) heavily rely on the gravity of the crime committed as one of the main criteria. The Rules of Procedure and Evidence (RPE) clearly support this prominence, since this factor is listed together with the treatment of similarly situated prisoners, the prisoner’s demonstration of rehabilitation, and any substantial co-operation of the prisoner with the Prosecutor. Empirical research confirms that most of the decisions delivered by these tribunals address the gravity of the crimes committed.Footnote 1 In a recent decision issued by the IRMCT, it was established that ‘while the gravity of the crimes is not the only factor in assessing an early release application pursuant to Rule 151 of the Rules, it is nevertheless a factor of fundamental importance’.Footnote 2

However, before the International Criminal Court (ICC), gravity does not play a role in the reduction of sentence, which is the equivalent mechanism to early release before this Court.Footnote 3 Neither Article 110 of the Rome Statute nor Rule 223 of the Rules of Procedure and Evidence, governing the reduction of the sentence, refer to gravity in the list of factors considered when deciding whether to reduce the convicted person’s sentence. Accordingly, the first Decision on the Review concerning the Reduction of the Sentence in Lubanga established that ‘unlike at other international criminal tribunals, the gravity of the crime is not a factor that in itself weighs for or against reduction of sentence’.Footnote 4 None of the decisions delivered thus far in Katanga or Al Mahdi even mention gravity.

Behind this radical change is the concern of incurring a double count when considering the gravity of the crime both in the sentencing and enforcement stages. In fact, after rejecting to examine the gravity of the crime in order to determine the reduction of the sentence, the International Criminal Court Panel in Lubanga pointed out the following:

the gravity of the crime for which the person was convicted is an integral and mandatory part of the original sentence imposed. Put differently, the sentence imposed reflects the Trial Chamber’s determination of a punishment proportionate to, inter alia, the gravity of the crimes committed. Thus, the Panel considers that generally this factor should not be considered again when determining whether it is appropriate to reduce a sentence.Footnote 5

Both case law and doctrine have warned against a double count of gravity. Nevertheless, traditionally, this double count has been applied to a different matter restricted to the sentencing phase, banning the consideration of the same factors in relation to the gravity of the crime as a sentencing factor and additionally as an aggravating circumstance. For Ambos, the prohibition of such double counting flows from the basic rationale of achieving a just and adequate punishment.Footnote 6 As noted by Khan, ‘this rule is consistent with the law and practice of the ad hoc Tribunals’.Footnote 7 Furthermore, it is in line with national practice.

International case law has been very clear in this regard. The ad hoc tribunals, as well as the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL),Footnote 8 have repeatedly applied this limit,Footnote 9 as has the ICC. For instance, in Lubanga, the Trial Chamber determined, regarding the crime of enlistment, conscription and use of children under the age of 15 to participate actively in the hostilities, that ‘the age of the children does not both define the gravity of the crime and act as an aggravating factor’.Footnote 10

The first Lubanga Decision concerning the reduction of his sentence took the double count ban to a different level, advocating its application in the sentencing and enforcement phases. As a consequence, in this logic, gravity could not be considered as a factor to grant the reduction of the sentence because it had already been considered at the sentencing stage. However, it seems difficult to evaluate the risk of recidivism that ultimately should justify early release without a reference to the gravity of the crime committed.

In this context, the aim of this article is to compare both models: early release including gravity as a factor and a reduction of the sentence without taking into account this factor. First, the article starts with a brief review of the concept of gravity as developed in the context of sentencing and pre-trial. Then, for the sake of the comparison, differences between early release, reduction of sentences and conditional release are examined.

To better grasp the consequences of including gravity in the early release assessment, an empirical analysis is carried out in the following section, examining all the early release decisions delivered until now by the ad hoc tribunals and IRMCT. Next, the premises and consequences of an early release assessment without gravity are studied. This is done not only by referring to the ICC but also by referring to the SCSL. In this tribunal, while gravity is not included as an express factor for early release, it still has been examined and taken into account in two of the decisions delivered so far.

Since the double count ban is the main argument put forward to leave gravity out of the early release assessment, a section is devoted to examining it further. Given that national jurisdictions also tend to use the gravity of the crime as one of the main sentencing guidelines, additional arguments are exposed, drawing on some examples of national instances that challenge the assumption that the double count ban is an unsurmountable obstacle.

Ultimately, it is argued that the double count ban should not be considered to apply at the enforcement stage and rather a full evaluation of rehabilitation should prevail. Hence, in order to entirely assess criteria that are strongly linked to rehabilitation, such as ‘the conduct showing dissociation from the crime’, reference should be made to features that traditionally define gravity, like the scale, nature, impact or harm caused to the victims, as a relevant part of the offending history of the convicted person. It is further argued that this does not amount to a double count, nor does it preclude per se access to early release.

2. Preliminary remarks on early release and the gravity of the crime

2.1 On the concept of gravity

The word ‘gravity’ appears 11 times in the Rome Statute. The gravity of the crime or the conduct is key to determining essential matters, such as when the conduct amounts to an international crime (Articles 7.1, 8bis 1 and 2), the admissibility of a case (Article 17), the initiation of an investigation (Article 53), the assessment of the merits of pretrial provisional release (Article 59.4), the imposition of life imprisonment (Article 77 but also Rule 145 RPE), the determination of the sentence (Article 78), and the decision on competing requests for the surrender of a person (Article 90.7).

Gravity is not defined as such in the Court’s core legal documents.Footnote 11 However, a number of factors delimit its scope. The Regulations of the Office of the Prosecutor of the ICC refer, providing a non-exhaustive list, to the ‘scale, nature, manner of commission, and impact’ of the crimes (Regulation 29.2) as factors to determine the gravity of a situation in the context of the initiation of an investigation or prosecution.

However, the most important indicators of the gravity of the crime, which have been repeatedly interpreted and thoroughly studied, are those outlined in Rule 145(1c) RPE in the context of sentencing. These factors refer jointly to gravity and the individual circumstances of the convicted person and include:

harm caused to the victims and their families, the nature of the unlawful behaviour and the means employed to execute the crime; the degree of participation of the convicted person; the degree of intent; the circumstances of manner, time and location; and the age, education, social and economic condition of the convicted person.Footnote 12

The list of indicators included in Rule 145.1(c) is not exhaustive, as shown by the use of the expression ‘inter alia’.Footnote 13

The ICC has included the following aspects under gravity: violence and the scale of crimes committed; the discriminatory dimension of the attack; the current situation in the region where the crimes were committed and the harm caused to the victims and their relatives; the consequences of victims’ suffering on society; the impact on the population; the risk exposure for the victims, and the particular cruelty with which the crimes were committed.Footnote 14

Another interpretation of gravity that has been progressively gaining relevance in ICC case law both in sentencing and early release stages is the differentiation between a crime’s abstract (gravity in abstracto) and concrete (gravity in concreto) gravity. The idea behind this approach is that gravity ‘is measured in abstracto, by analysing the constituent elements of the crime, and in concreto, in light of the particular circumstances of the case’.Footnote 15 This means that gravity is a two-fold concept that deals with the offence for which the accused is convicted and its commission by the offender.Footnote 16 The ICC has adopted this approach, at first implicitlyFootnote 17 but later on in an express manner.Footnote 18

Gravity in abstracto refers to the inherent gravity of the crime.Footnote 19 It is objective, also referred to as gravity in rem,Footnote 20 and is based on the subjective and objective elements of the crimeFootnote 21. Thus, it is linked to the controversial hierarchy within international core crimes and to protected legal interests.Footnote 22

While all the crimes included in the Statute are of extreme gravity, the ICC has acknowledged the need to assess the importance of each specific crime. For example, differentiating between crimes against persons and those ‘targeting only property’.Footnote 23 This argument was also used in Lubanga when referring to the devastating consequences for the victims of child soldier offences.Footnote 24 Furthermore, in Al Mahdi, the Trial Chamber found that the crime for which Al Mahdi was convicted was of significant gravity, noting nonetheless that crimes against property are ‘generally of lesser gravity than crimes against persons’.Footnote 25

Although it is decisive for gravity to be translated into an actual sentence,Footnote 26 as pointed out by Ambos, abstract gravity ‘can only be the starting point and must be complemented by concrete considerations focusing on the underlying offences and the circumstances of the particular case’, as abstract criteria are only of a limited value.Footnote 27

Gravity in concreto appears to be the most important consideration in sentencing.Footnote 28 This concept focuses on the particular circumstances of the case.Footnote 29 For Holá et al., this approach includes the actual commission of the crime and depends on the harm done and the culpability of the offender, in particular, regarding their position in the civil or military hierarchy or authority.Footnote 30 According to case law, the evaluation of gravity in concreto must be conducted from quantitative and qualitative standpoints.Footnote 31

In Ntaganda, Trial Chamber VI considered that the in concreto assessment needed to include:

(i) the gravity of the crimes, i.e., the particular circumstances of the acts constituting the elements of the offence; as well as (ii) the gravity of the culpable conduct, i.e., the particular circumstances of the conduct constituting elements of the mode of liability.

In addition, if they relate to the elements of the offence and mode(s) of liability, the factors stipulated in Rule 145 (1c) must also be considered along with other relevant factors since the list is open.Footnote 32

Although promising, this approach offers less information than expected, as the conclusions reached by the different chambers tend to be quite generic, leading to results such as considering ‘the gravity of the crime to be high’, ‘of considerable gravity’, ‘of lesser gravity’, ‘very serious’, ‘very high’, ‘especially grave’ or ‘undoubtedly very serious’.

For instance, in Ongwen, it is considered that the crime of enslavement as a crime against humanity is ‘in abstract a crime of considerable gravity’,Footnote 33 while in concreto, ‘the Chamber considers the gravity of the crime to be high’.Footnote 34 Pillaging is ‘of lesser gravity than the crimes against life, physical integrity, and personal liberty and dignity’Footnote 35 and conscripting or enlisting children under the age of fifteen years or using them to participate actively in hostilities ‘is undoubtedly very serious’.Footnote 36

2.2 Early release before the international tribunals

Early release is included in the core legal texts of the ad hoc tribunals, the IRMCT, ICC, and SCSL. However, significant differences exist among them. In this section, some of their main features will be described to better tackle the comparative analysis focused on the role of gravity.Footnote 37

2.2.1 Pardon and commutation, reduction of sentence and conditional early release

The ad hoc tribunals’ Statutes and RPE do not refer to early release but to pardon and commutation.Footnote 38 However, since the release of the Practice Direction on the Procedure for the Determination of Applications for Pardon, the Commutation of Sentences, or the Early Release of Persons Convicted by the International Tribunal, issued in 1999 by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), ‘early release’ has been the term chosen by most decisions. Footnote 39For the Mechanism, the RPE, issued in 2012, does refer to early release, as well as the Practice Direction.Footnote 40

At the Rome Conference, the terminology changed, favouring the expression ‘reduction of sentence’, which was considered to be ‘a more neutral wording’.Footnote 41 However, even if references to pardon and commutation have been banished, the term ‘early release’ is widely used. It is cited twice in Rule 223 RPE (c and d) and is repeatedly mentioned in the decisions delivered by the ICC on this matter.Footnote 42 Early release is hence used as a synonym for the reduction of sentences.

With respect to SCSL, Rule 124 RPE refers to early release since November 2011. Although the legal framework in the Statute and RPE barely differ from the ad hoc tribunals’, the Practice Direction has, since 2013, referred to conditional early release, thoroughly foreseeing the specific conditions to be imposed, as well as monitoring mechanisms and consequences of the infringement.Footnote 43

2.2.2 Decision-makers

In the ad hoc tribunals and IRMCT, the President is in charge of the decision regarding early release (‘there shall only be pardon or commutation of sentence if the President of the Mechanism so decides’),Footnote 44 although it is decided ‘in consultation with the judges’.Footnote 45 Consultation with other judges is compulsory and the decision has to be adopted ‘having regard to … the views of the other Judges consulted’.Footnote 46 However, the President’s decision is ultimately discretionary; ICTY jurisprudence has clearly pointed out that while the President is advised by other judges, he or she is not bound by their views.Footnote 47 These ‘judges’, according to the RPE, can be ‘the members of the Bureau and any permanent Judges of the sentencing Chamber who remain Judges of the Tribunal’.Footnote 48

The same approach is adopted by the SCSL, where decisions are delivered by the President ‘by a reasoned opinion in writing’, after consultation ‘with the Judges who imposed the sentence if available or, if unavailable, at least two other Judges’.Footnote 49

At the ICC, the prominence granted to the President in the ad hoc tribunals is transferred to the Court (‘the Court alone shall have the right to decide any reduction of sentence’, Article 110 of the ICC Statute). According to Rule 224, ‘three judges from the Appeals Chamber appointed by that Chamber’ will be in charge of the review. Although the RPE do not set any limitations, thus far, the panels were composed of judges who did not take part in either the Trial Chamber Judgment or the Appeal Judgment.

2.2.3 Time served

Initially, the national law of the country where the convicted person was serving the sentence was extremely relevant to early release since it was considered to trigger the proceedings. This led to a lack of equality among persons convicted by the same tribunal. Hence, the national law gradually lost relevance, as emphasis was placed on requiring that two-thirds of the sentence be served to ensure equality and foreseeability.

Once the enforcement supervision was taken over by the Mechanism, the two-thirds rule was adopted in the decisions issued, irrespective of the Tribunal that convicted them.Footnote 50 In May 2020, the IRMCT Practice Direction was amended, expressly referring to the fact that although ‘applications for pardon, commutation of sentence, or early release may be submitted at any time’ (paragraph 7), ‘a convicted person serving a sentence under the supervision of the Mechanism will generally be eligible to be considered for early release only upon having served two-thirds of his or her sentence as imposed by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), the ICTY, or the Mechanism’ (paragraph 8). Even if there is some controversy, in theory, this is not a presumption since it ‘does not guarantee that release will be granted’.Footnote 51

The time requirement was initially handled as a precondition that could weigh in favour or against early release. Later on, it became a threshold. As a result, applications for early release were not examined in depth unless two-thirds had been served (or the application is based on humanitarian grounds).Footnote 52

At SCSL, both the RPE (Rule 124) and the Practice Direction (Section 2) expressly set eligibility for consideration for conditional early release upon serving two-thirds of the total sentence.

As for the ICC, already in a preliminary stage of the negotiations, it was proposed to establish a specific period of a sentence that had to be served before the review.Footnote 53 This limit sets eligibility, but it does not imply a presumption of early release once this point in time is reached.Footnote 54 For determinate sentences, the threshold was set at two-thirds of the sentence. More intricate was the discussion on life sentences, and in such cases, this specific period was set to 25 years.Footnote 55

2.2.4 Preconditions

According to the Statutes of the ad hoc tribunals and the IRMCT, pardon and commutation will be decided ‘on the basis of the interests of justice and the general principles of law’. The Rules further specify that:

in determining whether pardon or commutation is appropriate, the President shall take into account, inter alia, the gravity of the crime or crimes for which the prisoner was convicted, the treatment of similarly situated prisoners, the prisoner’s demonstration of rehabilitation, as well as any substantial cooperation of the prisoner with the Prosecutor.Footnote 56

Hence, the importance granted to gravity is clear.

At SCSL, the requirements are more comprehensive and include successful completion of any remedial, educational, moral, spiritual or other programme to which the prisoner was referred within the prison; proof that the prisoner is not a danger to the community or to any member of the public; compliance with the terms and conditions of his imprisonment; respect for the fairness of the process by which the prisoner was convicted; refraining from incitement against the peace and security of the people of Sierra Leone while incarcerated; and positive contribution to peace and reconciliation in Sierra Leone and the region, such as public acknowledgement of guilt, public support for peace projects, public apology to victims, or victim restitution. Gravity is not expressly a factor to evaluate. Among the many documents gathered by the Registrar in the process, reference is made to an assessment of the ‘likelihood of the convicted person committing criminal offences’ (Practice Direction, Section 5).

At its turn, the Rome Statute enumerates the factors that judges shall consider to reduce a sentence. Having served two-thirds of a sentence is also not a factor as such but rather the trigger for the commencement of the sentence review under Article 110(3).Footnote 57

Factors are listed in Article 110.4 ICC St and in Rule 223.a) to e) of the RPE. Article 110.4 refers to:

the early and continuing willingness of the person to cooperate with the Court in its investigations and prosecutions; the voluntary assistance of the person in enabling the enforcement of the judgements and orders of the Court in other cases, and in particular providing assistance in locating assets subject to orders of fine, forfeiture or reparation which may be used for the benefit of victims; or other factors establishing a clear and significant change of circumstances sufficient to justify the reduction of sentence, as provided in the Rules of Procedure and Evidence.

Rule 223 adds:

the conduct of the sentenced person while in detention, which shows a genuine dissociation from his or her crime; the prospect of the resocialization and successful resettlement of the sentenced person; whether the early release of the sentenced person would give rise to significant social instability; any significant action taken by the sentenced person for the benefit of the victims as well as any impact on the victims and their families as a result of the early release; individual circumstances of the sentenced person, including a worsening state of physical or mental health or advanced age.

The gravity of a crime is no longer included among the factors expressly relevant to reducing a sentence.

3. The role of gravity in early release

3.1 Gravity as a factor for early release before the ad hoc tribunals

The first model examined is adopted by the ad hoc tribunals and the IRMCT and holds gravity as a key factor in access to early release. Given the clear legal basis provided by the RPE, the importance of gravity as a factor in access to early release is rarely challenged.Footnote 58 With the aim of gaining a deeper understanding of the implications of taking gravity into account in the early release assessment, an empirical and quantitative study of the decisions delivered by the tribunals has been carried out.

3.1.1 Data collection

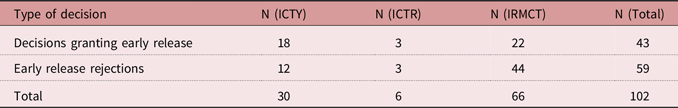

Data collection was restricted to those tribunals that expressly include gravity among the early release factors (ICTY, ICTR, and IRMCT). The sample (see Table 1) includes a total of 102 decisions delivered between June 1999 and February 2023, 43 of them granting early release and 59 rejecting it. Twenty-nine percent were delivered by ICTY, 5,8 percent to the ICTR and 64,7 percent to IRMCT.

Table 1. Number of early release decisions analysedFootnote 60

These 102 decisions regard 73 individuals, since some prisoners apply several times.Footnote 59 Sentences being served range from fine and arrest (contempt cases) to life sentences (Table 2).

Table 2. Sentences being served

All data was obtained from the decisions published in the Unified Court Records Database and analysed by analytical software IBM SPSS 28.0, using descriptive statistics procedures. The main purpose of the research is to examine the role of the gravity of the crime in early release decisions. For each decision delivered, twelve variables were collected.

First, general variables that can be indirectly linked to the gravity of the crime as a factor to decide early release have been examined. The date of deliveryFootnote 61 (i) could help identify trends regarding the role of gravity in the final decision. The organ delivering the decision (ii) might also be relevant in order to determine whether certain tribunals have granted greater importance to the gravity of the crime. In view of the relevance of the President, who has the discretionary power to determine early releases, it is important for the analysis to record the identity of the President delivering the decision (iii), as there could be differences in terms of the justification of the decisions adopted. To complement this aspect, another variable is the other Judges’ views (iv). As was pointed out, the President ought to consult with other judges, even if the President is not bound by their views. It was therefore recorded whether the panel of judges consulted agreed with the final decision or whether they dissented, which could also ultimately be linked to the gravity of the crime.

As for the sentence being served, the category of crime committed (v) is analysed. Since the aim of the analysis is to determine the role of gravity, data regarding the crime committed take special note of cases including genocide and extermination. Sentence length (vi) is recorded as a 9-category variable encompassing fine and arrest, five years or less, six to ten years, 11 to 15 years, 16 to 20 years, 21 to 29 years, 30 or more, 40 or more, and life sentences.

Directly linked to the early release decision, the number of total requests of early release (vii) is taken into account, as a convicted person may reapply for early release in case of rejection. The time served (viii) is of crucial importance, whether used as a threshold to apply for early release or as a factor that might compensate the gravity of the crime committed. This variable is recorded in two categories: whether the applicant had served less than two-thirds of the sentence or two-thirds or more had been served. Finally, it is recorded whether early release was granted or denied (ix).

The last group of variables concern data related to the grounds to grant or deny early release, hence directly linked to the gravity of the crime as an explanatory factor. First, the grounds recorded according to the RPE wording (x): gravity of the crime or crimes for which the prisoner was convicted, the treatment of similarly situated prisoners, the prisoner’s demonstration of rehabilitation and substantial co-operation of the prisoner with the Prosecutor, as well as combinations of these grounds. Also, whether medical grounds (xi) were present. Although not expressly included, this factor has been taken into account by the ad hoc tribunals and IRMCT and is considered to be encompassed under reference to rehabilitation. A serious illness or condition requiring medical treatment, surgery, or daily assistance may be deemed to require early release, defusing the explanatory power of the gravity of the crime in the final decision. Finally, reference to the gravity of the crime (xii) is examined on three levels: if gravity is at all examined; if the analysis refers to gravity in abstracto or in concreto; and gravity’s weight in the decision, since decisions tend to establish whether gravity weighs in favour, not against or against early release, recording some nuances in case gravity weighs heavily or very heavily against it.

3.1.2 Results

According to the data sampled, while 57,8 percent (N=59) of the applications were denied, 42,1 percent (N=43) of the applications were granted. Although ten presidents delivered decisions on early release, most of them were issued by President Theodor Meron (44 percent, N=45) and President Carmel Agius (30,4 percent, N=31), followed by President Patrick Robinson (13,7 percent, N=14). President Meron granted 62 percent of the applications received under his mandate as Presiding Judge of the Mechanism (from 1 March 2012 to 18 January 2019), and President Agius granted only 6,4 percent of the requests received under his mandate (from 19 January 2019 until 30 June 2022), confirming a turn to a more restrictive interpretation of the prerequisites leading to early release.

Most of the decisions granting early release (65 percent) refer to sentences between 11 and 20 years, which seems reasonable since this range is the most commonly imposed, at least by the ICTY (see Table 3).Footnote 62 As for the gravest cases, only once has early release been granted for a sentence higher than 31 years (life sentence), and it was an exceptional case that was based on medical grounds.Footnote 63 Rejection rates support the idea that the graver the sentence, the lower the chances of accessing early release.

Table 3. Early release by sentence

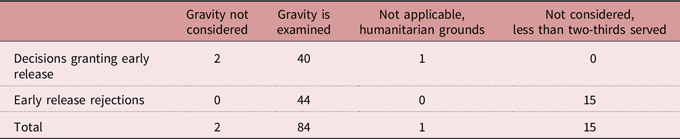

Gravity was addressed in 82,4 percent (N=84) of the decisions and was not considered in the remaining decisions (17,6 percent, N=18). Various reasons could explain the lack of an analysis of the gravity of the crime in this last group of decisions. In one case, the decision was based solely on humanitarian grounds, arguably making gravity irrelevant.Footnote 64 In two decisions, one (or the only) ground to grant early release was co-operation with the prosecutor or rehabilitation. Nevertheless, even in cases where early release decisions are made on these grounds, gravity tends to be examined; thus, these two cases are exceptional (see Table 4).Footnote 65

Table 4. Relevance of gravity in decisions granting or denying early release

In the rest of the decisions where gravity was not addressed (N=15), the applicants had served less than two-thirds of the sentence. While in the first decisions delivered by the tribunals, having served two-thirds of the sentence was considered a factor either in favour of or against early release,Footnote 66 later it was interpreted as ‘an admissibility threshold’Footnote 67 and, therefore, when the applicant had served less than two-thirds of the sentence, the rest of the factors (including gravity) were not further examined.Footnote 68

Regarding the aspects considered when examining gravity, 45 percent of the decisions that referred to gravity approached both gravity in abstracto and in concreto, although not expressly adopting this terminology. Hence, attention was given both to the gravity of the crime and the particular responsibility of the applicant, even if the stress was usually placed on gravity in concreto, discussing this aspect more at length. In six decisions, only gravity in concreto was addressed, and as many as 32 only focused on gravity in abstracto. Again, the explanation of these differences could be linked to a different approach taken by the different presidents. President Meron mainly examined the gravity of the crime in abstracto in 23 of his decisions, while the decisions delivered by President Agius tend to examine gravity only if the two-thirds threshold is met and then generally both in concreto and in abstracto.

Decisions usually point out whether gravity appears to be in favour of or against early release. The gravity of the crime has never been considered a favourable factor for early release.Footnote 69 Even in cases regarding contempt, gravity is deemed a factor against early release.Footnote 70 Only one decision issued by ICTY established that the gravity of the crime did not weigh against the request for early release in a case of plunder and misappropriation of property by the subordinates under the command of the convicted person.Footnote 71

In some instances, the gravity of the crimes committed is considered to play ‘strongly against’, ‘heavily against’, ‘very strongly against’, or ‘very heavily against’ early release. However, these nuances are only used by some presidents. For instance, President Agius made this distinction, while President Meron did not, referring only to gravity as ‘against’ early release.

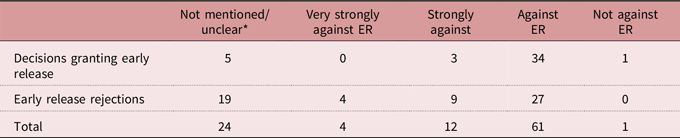

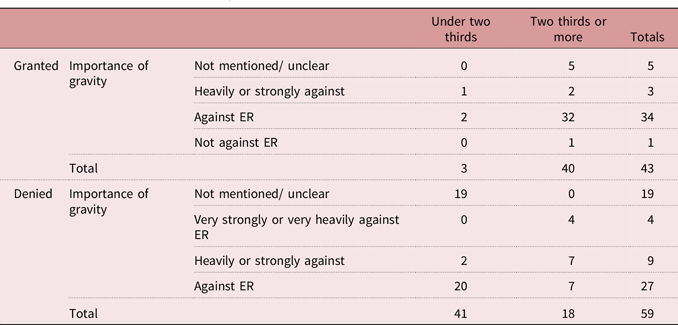

Even though, as already pointed out, gravity tends to go against early release, 36,2 percent of the applications were nevertheless granted, even if gravity weighed strongly against or against early release. Put differently, in 86 percent of the decisions granting early release, gravity was a factor against it (see Table 5).

Table 5. Relevance of the gravity of the crime in the decisions on early release delivered by the ICTY, ICTR, and IRMCT

* Not mentioned either because gravity is not addressed or because gravity is addressed but its weight in the final decision is not expressly determined.

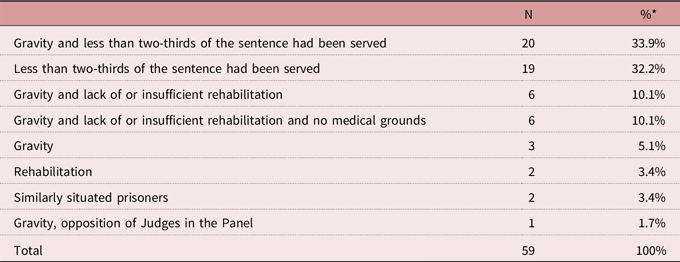

Regarding the grounds on which the decisions are based, the analysis differs in the decisions granting and denying early release. Out of the 59 decisions denying early release, gravity was repeatedly used either solely (N=3) or together with other grounds (N=33 decisions) in a total of 61 percent of the rejections (see Table 6).

Table 6. Grounds to deny early release

* Percentage of the total of rejections.

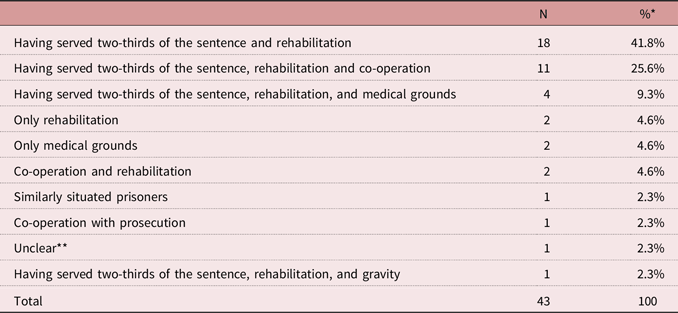

As was pointed out, a number of decisions in which gravity was considered to weigh against early release (or even strongly against it) were ultimately granted. In these cases, other factors outweigh gravity. Rehabilitation, alone (two) or together with other factors (36), were the most important considerations to grant early release (see Table 7).

Table 7. Grounds to grant early release

* Percentage of the total of applications granted.

** Unclear as the reasons were redacted for confidentiality.

Never has early release been granted if gravity was considered to weigh very strongly (or very heavily) against it. Three decisions granted early release although gravity played strongly (or heavily) against it, relying on medical grounds solely (N=1) or together with other grounds (N=1), and co-operation with the Court (N=1). In the cases where early release was granted although gravity was considered to weigh against it, rehabilitation was among the grounds to justify the decisions in most cases either solely or together with other grounds (94 percent of the cases).

As established, having served two-thirds of the sentence was initially another factor that could weigh in favour or against early release, turning into a threshold for the application later on. Even though there can be important nuances among both interpretations, in the end, early release is granted only very exceptionally before two-thirds of the sentence are served (6,9 percent of total decisions granted, N=3). In the cases where gravity weighed heavily against (N=1) or against (N=2), co-operation with the Prosecutor or medical grounds explained the decision.

The so-called ‘two-thirds presumption’ is not entirely confirmed by the data.Footnote 72 In 32 percent of the rejections, the individuals had already served two-thirds or more of the sentence,Footnote 73 partly relying on the gravity of the crime (see Table 8).

Table 8. Time served in relation to the gravity

Humanitarian grounds were put forward in 31 cases. In 21 of them, these grounds were dismissed, although in two of them, early release was ultimately granted based on other grounds. In the remaining cases (N=10), these medical reasons were accepted, granting early release in all but one, where the prisoner had not yet served two-thirds of the sentence.Footnote 74 In these nine decisions, gravity was considered to weigh heavily against (N=2) or against early release (N=6).Footnote 75

In most cases (72,5 percent, N=74), the other Judges consulted are generally unanimous and hold the same view as the final decision. In 23 of the decisions examined, it is not indicated whether the Panel supported the decision. Only in one case the Panel was not favourable to an early release application that was granted. The gravity of the crime was considered to weigh against early release, but it was granted relying on rehabilitation and co-operation with the Court. In two cases, the Panel was in favour of granting it, although it was rejected. In two other cases, the Panel was not unanimous, and the applications were denied.

Regarding the crimes for which they were convicted, in 25 of the decisions the convictions included the crime of genocide. Seven of these applications were granted (28 percent), while the remaining 18 were rejected. For extermination as a crime against humanity, out of the 24 applications including this crime, seven were granted (29 percent). This is lower than the average 42,1 percent of decisions granted in the sample.

The latest decisions issued by the Mechanism point in this direction. In the Decision on the Application for Early Release of Radislav Krstić, delivered on 15 November 2022, regarding gravity, the President of the Mechanism states that:

In relation to the gravity of crimes, past decisions have established that:

-

(i) as a general rule, a sentence should be served in full given the gravity of the crimes within the jurisdiction of the ICTR, the ICTY, and the Mechanism, unless it can be demonstrated that a convicted person should be granted early release;

-

(ii) while the gravity of the crimes is not the only factor in assessing an early release application pursuant to Rule 151 of the Rules, it is nevertheless a factor of fundamental importance;

-

(iii) the graver the criminal conduct in question, the more compelling a demonstration of rehabilitation should be; and

-

(iv) while the gravity of the crimes cannot be seen as depriving a convicted person of an opportunity to argue his or her case, it may be said to determine the threshold that the arguments in favour of early release must reach’.Footnote 76

The data examined could support these assertions. More than half of the applications for early release are rejected (57,8 percent), substantially more if we consider only the decisions delivered the last years (as many as 93 percent were denied under President Agius). Gravity is examined in most decisions (82 percent), generally only omitted when two-thirds have not been served or where medical grounds support the decision. Applications regarding higher sentences (life sentence, 31 to 45 years or 21 to 30) are rejected on a very high percentage (90 percent, 100 percent, and 64 percent respectively) and those granted respond to exceptional reasons.

In conclusion, gravity is carefully addressed in most of the decisions examined and plays an important role in deciding early release, having a great impact on the outcome. It is nevertheless not an unsurmountable obstacle to access early release, as it can be outbalanced by other considerations, in particular, rehabilitation, and co-operation with the tribunal.

3.2 Early release without the gravity of the crime

As already pointed out, both the SCSL and ICC do not include the gravity of the crime as a factor for early release. In this section, these two cases will be examined, analysing the reasons and consequences of this approach.

3.2.1 Before the ICC

Among the many features that differentiate early release before the ad hoc tribunals and the IRMCT and reduction of sentence before the ICC, the role attributed to gravity stands out. As noted, gravity is no longer included among the factors relevant to reducing a sentence before the ICC and is, therefore, no longer expressly used for this purpose. In its first decision, the Panel clearly stated the following:

the gravity of the crime is not a factor that in itself weighs for or against reduction of sentence. Rather, the gravity of the crime for which the person was convicted is an integral and mandatory part of the original sentence imposed. Put differently, the sentence imposed reflects the Trial Chamber’s determination of a punishment proportionate to inter alia, the gravity of the crimes committed. Thus, the Panel considers that generally this factor should not be considered again when determining whether it is appropriate to reduce a sentence.Footnote 77

Since then, no other decision has mentioned gravity. The rationale seems to be to avoid a double count. For van Zyl Smit, given that the gravity of the crime is ‘presumably already the most powerful determinant of the sentence’, considering it again at the release stage amounts to double jeopardy, seeming ‘palpably unjust’.Footnote 78 Holá and van Wijk argue that ‘factoring in the gravity of crimes is actually a redundant exercise’.Footnote 79

However, the gravity of the crime could indirectly play a role when assessing the rehabilitation of the convicted person.Footnote 80 Although rehabilitation is generally considered a ‘broad but somewhat slippery concept’,Footnote 81 still lacking a generally accepted operative definition,Footnote 82 different approaches have been developed over time, sharing a common objective: decreasing the chance of reoffending. In some of these theories, gravity is indirectly considered through the relevance of anti-social behaviour (for instance, in the RNR model) or a risk assessment that directly or indirectly includes the gravity of the crime committed or acceptance of responsibility for their actions.

In the specific case of international criminals, the thesis that rehabilitation needs to be differently interpreted has gained increasing prominence in recent years. Holá and van Wijk point out that ‘according to [international] case law, rehabilitation is a process of change and reflection aimed largely at reducing the risk of recidivism’.Footnote 83 This risk should to be pondered taking into account indicators of the gravity of the crime such as harm caused or the manner of commission.

Before the ICC, rehabilitation is included, among others,Footnote 84 in Rule 223.a, which literally refers to ‘the conduct of the sentenced person while in detention, which shows a genuine dissociation from his or her crime’.Footnote 85 In the decisions delivered to date, the Panels have repeatedly stressed that good conduct while serving a sentence is not enoughFootnote 86 and that it is required that the person ‘demonstrates a genuine dissociation from his or her crime’, by ‘accepting responsibility and expressing remorse for having committed those criminal acts’.Footnote 87 This can hardly be assessed without reference to the crime, including its gravity, as it will need to be evaluated differently, for instance, in the case of crimes against persons versus those against property or if the crime was committed with discriminating motives or with particular cruelty.

When addressing Lubanga’s dissociation from the crime, it was deemed that he ‘did not acknowledge his own culpability for conscripting and enlisting children under the age of fifteen years old and using them to participate actively in hostilities or express remorse or regret to the victims of the crimes for which he was convicted’.Footnote 88 In the case of Katanga, in order to prove dissociation with the crimes, he stated at the Sentence Review Hearing having come to terms with the role he personally played in the attack on Bogoro, as well as with the decree and scope of suffering inflicted upon the victims of that attack. The Panel found there was evidence of this dissociation, acknowledging that ‘Mr. Katanga has repeatedly and publicly taken responsibility for the crimes for which he was convicted, as well as expressed regret for the harm caused to the victims by his actions.’Footnote 89

It could ultimately be argued that rehabilitation is generally not considered the primary goal of punishment at the international tribunals. Although there is no uniform approach,Footnote 90 the ad hoc tribunals have usually referred to deterrence and retribution,Footnote 91 giving rehabilitation a lesser relevance.Footnote 92 Before the ICC, retribution and deterrence are still considered primary objectives of punishment.Footnote 93 The Court has repeatedly stressed that, although reintegration of the convicted person is of relevance, ‘in particular in the case of international criminal law, this goal cannot be considered as primordial’,Footnote 94 ‘should not be given undue weight’,Footnote 95 or is of limited relevance in the context of international criminal law.Footnote 96

However, even if rehabilitation is not one of the main purposes of punishment and is only secondary when sentencing, prioritizing reintegration during the enforcement of sentences would be in line with national practice in many countries and, most importantly, with Article 10.3 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political rights, which requires that ‘the penitentiary system shall comprise treatment of prisoners the essential aim of which shall be their reformation and social rehabilitation’.

3.2.2 Before the SCSL

Even if the gravity of the crime committed is also not considered as a factor in assessing early release, two of the four decisions issued thus far by the Residual Special Court for Sierra Leone expressly refer to gravity. In the Decisions on the Conditional Release of Fofana and Gbao, the gravity of the crimes committed is thoroughly covered, quoting paragraphs of the Judgment where this issue is addressed.

First, in 2014, in the Decision on the Conditional Early Release of Fofana, these considerations led to the conclusion that ‘the high gravity of the crimes for which Fofana was convicted is a factor that weighs against granting the application for early release’, in the same manner as in the ad hoc tribunal’s practice.Footnote 97

Second, gravity was also examined in the 2020 Decision on the Conditional Early Release of Gbao. While acknowledging that gravity is not a factor under Article 8 Paragraph (D) of the Practice Direction, the Decision summarized the gravity of the crimes committed, quoting excerpts of the trial, sentencing and appeals judgements, concluding that ‘Gbao’s conduct was evaluated by the Special Court and reflected in his sentence’.

Regarding his application for early release, the decision pointed out that:

the extent to which prison has led to the rehabilitation of the tendencies identified by the Special Court in the commission of his crimes will be relevant to determine whether it is safe for Gbao to serve part of his sentence in the community. Footnote 98

This reference to the ‘tendencies identified’ by the Court could be understood as an indirect reference to the gravity of the crimes committed, considered in the context of the rehabilitation evaluation.

3.3 Synthesis

The empirical study of the decisions delivered by the ad hoc tribunals and the IRMCT has shown that the gravity of the crimes committed was repeatedly used to justify the denial of early release (in as many as 62,7 percent of the decisions rejecting early release). Gravity is an important factor, as shown by the higher percentages of rejection in the case of individuals serving graver sentences (life sentences, 31 to 45 years). However, it also shows that the gravity of the crimes committed does not necessarily preclude access to early release, since it can be compensated by other factors such as collaboration with the Prosecution or rehabilitation.

At its turn, the ICC does not assess gravity as a stand-alone factor. Nevertheless, it is argued in this article that gravity is still indirectly considered, when examining ‘the conduct of the sentenced person while in detention, which shows a genuine dissociation from his or her crime’. This factor is strongly linked to rehabilitation, where reference to the crimes committed is almost inevitable.

The decisions delivered so far, consider that such dissociation is not merely shown by good conduct while in detention, but by accepting responsibility for the crimes committed, recognizing the crimes, or expressing remorse for the victims. To show dissociation is not enough to express opposition to a particular criminal act in the abstract, but to accept responsibility and express remorse for having committed those criminal acts.Footnote 99 This can hardly be done without reference to those aspects linked to gravity, such as the harm caused to the victims, the nature of the unlawful behaviour and the means employed to execute the crime, degree of participation of the convicted person, degree of intent or the circumstances of manner, time, and location.

Hence, the approach taken in the SCSL Decision on the Conditional Early Release of Gbao, expressly connecting rehabilitation with the tendencies identified in the commission of his crimes seems particularly suited. Completely omitting gravity when assessing early release seems to offer an incomplete assessment on this regard.

4. Is the double count ban a real obstacle? A reply from a national perspective

For the ICC, avoiding a double count of circumstances has been a consistent interpretative guideline when addressing early release. Despite the great differences among national systems, in a number of them, when defining early/conditional release or parole, gravity still tends to play a role, even if it was already a key factor when sentencing and the double count ban is fully functional through the well-established principle of non bis in idem.

Generally, special preventative considerations should be the basis for deciding upon early release. Consequently, aspects such as the person’s behaviour while in prison, participation in rehabilitative programmes or activities or, more generally, evidence of the prisoner’s socialization are particularly relevant.Footnote 100 However, the gravity of the crime can also be relevant in different ways.

First, gravity can be a factor used to decide on early release. For instance, in Austria, to access early conditional release before having served two-thirds of the sentence (when half of the sentence has been served), the ‘seriousness of the crime’ (‘die Schwere der Tat’) will be considered.Footnote 101

Second, another approach that integrates gravity imposes stricter rules to access early release for those who have committed particularly grave crimes. This is the case for Finland; regarding decisions about conditional release from life imprisonment, the Criminal Code clearly states that ‘attention shall be paid to the nature of the offence or offences that had led to the sentence of life imprisonment’ (Section 10 (1099/2010), Criminal Code).

Third, the gravity of the crime committed can also be considered when assessing the recidivism risk to determine the individual prognosis. For instance, in the German Criminal Code (StGB), the equivalent of early release is the suspension of the remainder of the sentence (Aussetzung des Strafrestes bei zeitiger oder lebenlanger Freiheitsstrafe). In theory, only considerations of special prevention are taken into account.Footnote 102 To grant a suspension, it is required that the suspension ‘can be justified having regard to public security interests’. This assessment is deemed to include the crime committed and the legal interests affected.Footnote 103 Section 57.1 establishes the following:

The decision is, in particular, to take into consideration the convicted person’s character, previous history, the circumstances of the offence, the importance of the legal interest endangered should the convicted person re-offend, the convicted person’s life circumstances and conduct whilst serving the sentence imposed, and the effects which such suspension are expected to have on the convicted person.

Some of the aspects listed are clearly linked to gravity. This is the case of ‘the circumstances of the offence’ or ‘the importance of the legal interest endangered should the convicted person reoffend’.Footnote 104

Furthermore, in the case of life sentences, according to Section 57a, the court will need to consider ‘the particular severity of the convicted person’s guilt’, which, while being criticized for being particularly imprecise,Footnote 105 is generally interpreted to refer to both the crime and the perpetrator.Footnote 106

Similar to German legislation, in Spain, although the gravity of the crime committed is not a criterion as such in the Criminal Code, it is relevant when assessing the recidivism risk. Section 90 of the Criminal Code states that:

to decide on the suspension of the execution of the rest of the sentence and the granting of parole, the prison supervision judge will assess the personality of the prisoner, criminal history, the circumstances of the crime committed, the relevance of the legal interests that could be affected should the convicted person reoffend, their conduct while serving the sentence, their family and social circumstances and the effects that can be expected from the suspension of execution itself and compliance with the measures that were imposed.

Factors such as ‘criminal history, the circumstances of the crime committed, the relevance of the legal interests that could be affected should the convicted person reoffend’ are necessarily linked to the gravity of the crime committed. In fact, research shows that the criminal record plays a crucial role in deciding whether an offender should be refused early release.Footnote 107

Finally, in England and Wales, ‘when deciding whether a prisoner meets the test for release, the Parole Board considers a range of information in order to assess the individual’s risk of reoffending and the manageability of such risk when in the community’.Footnote 108 The first stage of all parole reviews involves one Parole Board member reviewing the prisoner’s dossier. The dossier is a collection of documents about the prisoner, including reports and information about their offence, progress made in custody, and a risk management plan.Footnote 109 In the framework of analysis used by the Parole Board, analysis of offending behaviour is critical and includes the offender’s history, such as the offence type committed, the factual details of the offence, previous convictions, or the impact of the offence.Footnote 110

5. Conclusions

In this article, two models have been compared: early release including gravity as a factor and early release without direct reference to it. For the first model, over time, the ad hoc tribunals and the IRMCT have been progressively offering more solid and well-reasoned early release decisions. Gravity is included among the indicators, leading to a more complete and thorough analysis of the case.

The ICC Statute and RPE do not include gravity as an autonomous factor for the reduction of sentence. Furthermore, it appears to be settled that making reference to the gravity of the crime at sentencing and again when making decisions on reduction of sentence is unfair. The legal basis of such a prohibition in the enforcement stage is uncertain. In fact, national instances where this principle is fully functional and very settled do not seem affected by such restrictions and refer to the gravity of the crime either directly or indirectly in early release decision-making.

The perception that it would be unfair to again take gravity into account may arise from the presumption that those who commit grave crimes already serve long sentences and that considering gravity again would hamper their chances of accessing reintegration through early release, somehow amounting to double counting. This is not necessarily the case. As shown by the ad hoc tribunals’ experience, although to a lesser extent, even criminals who committed grave crimes might eventually access early release relying on other indicators such as rehabilitation.

Moreover, assessing rehabilitation without considering the gravity of the crime committed appears challenging. Rather, the arguments put forwards by the last IRMCT Decision on Early Release seem very reasonable: ‘the graver the criminal conduct in question, the more compelling a demonstration of rehabilitation should be’. To fully evaluate the rehabilitation of Al Mahdi or that of Ntaganda, the nature and magnitude of their crimes, the legal interests affected by them, and even aggravating circumstances, such as the commission of the crime with particular cruelty or where the victim is particularly defenceless, should be considered.

Disregarding gravity implies not taking into account the aspects that, according to the ICC’s core legal documents, define it, such as the scale, nature, manner of commission, impact, nor the harm caused to the victims and their families, means to execute the crime or the degree of participation and intent. Therefore, the real question is whether it seems possible to fully evaluate dissociation from the crime (or prospect of resocialization) without reference to these aspects.

Other indicators for early release relevant to the ICC also lead to a reassessment of issues already evaluated at the sentencing stage. In the same line, the Court has made special efforts to avoid double counting, differentiating those aspects already evaluated in the sentencing stage, leading to counterintuitive interpretations. For example, considering that remorse is not relevant if it was already shown before the conviction and ongoing during enforcement, stressing the importance of the change in circumstances. The logic behind it is that remorse already reduced the initial sentence when it was considered a mitigating circumstance. Therefore, it would seem illogical, or simply unfair, to consider remorse again to further reduce the sentence.

Granting the double count such an important role would seem to assume that the reduction of sentence is somehow perceived as yet another phase in the sentencing process as opposed to a part of the enforcement. This assumption could be coherent given certain features of the reduction of sentence (namely, the unconditional and irreversible nature of these decisions, even when reoffending), but distances it from an early release as an integral part of enforcement and linked to rehabilitation, as commonly conceived in national instances. From this perspective, interpretation of the indicators should not be driven by the goal to avoid double counting but simply to evaluate rehabilitation, as accurately as possible, using all the information available, including the offending history.