In 1926, the Hollywood studio Fox Film launched a Feminine and Masculine Photogenic Beauty Contest to search for their next “Latin” star in Brazil, Chile, and Argentina. In Brazil, one male and one female winner would win a grand prize: a trip to Hollywood and a one-year acting contract. If the winners demonstrated “aptitude for the cinematographic art,” Fox Film would offer them an additional four-year contract.Footnote 1 If they lacked this aptitude, Fox would at least pay for the actors’ passage back to Brazil. In order to be successful, the winning contestants had to be “white with Latin blood” and exhibit “photogenia,” two elusive terms loaded with contentious racial, national, gendered, and sexual significance. Brazilian film intellectuals seized the contest as an opportunity for the winners to “elevate the name of Brazil” in Hollywood. Aspiring stars submitted their photographs, body measurements, and their fervent hopes for success. Beauty, or more specifically the concept of “photogenia,” could bring the promise of stardom and prestige on cinema’s largest stage, not only for the winners but for all of Brazil.

The Fox Film Photogenic Beauty Contest began as a Hollywood invention, a publicity campaign in which North American studio executives established the parameters of acceptable beauty and decided the ultimate winners. Nevertheless, film critics, intellectuals, and aspiring actors in Brazil interpreted these parameters, constructing concepts of beauty and race in a transnational context.Footnote 2 Although Brazilians who entered the contest fashioned their faces, bodies, and mannerisms to fit Fox Film’s standards of beauty, they were not derivative images of Hollywood’s exotic ideals.

Rather, the Fox Film contest illuminates how Brazilians positioned themselves within multiple, competing discourses of racialized beauty. Brazilian film critics propagated early twentieth-century eugenic ideologies that privileged whiteness. At the same time, intellectuals and film fans recognized Hollywood’s vogue for stars with exotic sexual allure, a quality at odds with the Brazilian eugenic definition of whiteness. Which type of beauty would be Brazilians’ tool to conquer Hollywood? Brazilian film intellectuals resolved this contradiction by characterizing the winners as white individuals capable of performing Hollywood fantasies of nonwhite sexuality. While the Fox Film Beauty Contest did not upset racial hierarchies or the supremacy of white beauty in Brazilian intellectual discourse, it indicated how the transnational contours of cinema offered a liminal space for competing standards of racialized beauty.

Beauty and Whiteness in Brazil

When the Fox Film studio launched the contest, it waded into dynamic intellectual and popular discussions regarding beauty, race, and national identity in Brazil. In the early twentieth century, Brazilian intellectuals, writers, and artists incorporated medical discourse related to eugenics to define beauty as coterminous with a racialized ideal of whiteness. In contrast to the Mendelian eugenics of Germany and the United States, where eugenicists sought to engineer race through reproduction and mass sterilization, Latin American intellectuals selectively combined Mendelian and neo-Lamarckian eugenics, the latter which maintained that environmental factors were the keys to racial uplift.Footnote 3 Brazilian public health officials embarked on campaigns to vaccinate, sanitize, educate, and otherwise lift populations out of both poverty and racial degeneracy.Footnote 4

Eugenicists and public officials associated blackness not only with backwardness and poverty but with ugliness and deviant bodies. In contrast, they associated whiteness with progress, health, education, sexual chastity, and beauty (Reference DávilaDávila 2003). Centering beauty within early twentieth-century eugenic ideology, Alvaro Jarrín argues that beauty was the means to demarcate the boundaries of national belonging. “If ugliness racialized rural workers as inferior and sickly, beauty served as its mirror image and became a highly desirable trait that marked the superiority of the Brazilian elites” (Reference JarrínJarrín 2017, 37).Footnote 5 Mônica Raisa Schpun has similarly addressed the imbrication of health, beauty, and whiteness and how women in the 1920s participated in sports to cultivate idealized thin, white bodies (Reference SchpunSchpun 1999).

Within this ideological context, beauty contests emerged as key forums to debate the racialized boundaries of beauty and identity in Brazil. Workers’ associations, Afro-Brazilian social clubs, and ethnically based mutual aid societies held beauty contests and debated the parameters of female beauty according to national, racial, ethnic, class, and regional identities (Reference BesseBesse 2005, 109).Footnote 6 However, within nationally circulating periodicals aimed at the elite and growing population of urban professionals,Footnote 7 newspaper editors and beauty contest judges consistently upheld the eugenic ideal of whiteness as a qualifier of national beauty. In 1923, Belmonte (pseudonym of Benedito Carneiro Bastos Barret), a famed satirical cartoonist from São Paulo, poked fun at the incongruity of nonwhiteness and beauty. Printed in the São Paulo newspaper Folha da Noite, “The Ugliest Woman of Brazil” cartoon features a dark-skinned woman in elegant dress but with “ugly” features (Figure 1). The oversized bow adds a comic, provincial touch to her look despite the dress and jewels. She is surrounded by bags of money and jewels; the caption reads, “She will receive $50,000 worth of prizes, at least as a bit of consolation.”

Figure 1 Belmonte, “A mais feia do Brasil,” Folha da Noite, May 5, 1923. Acervo Folha, https://acervo.folha.com.br/index.do.

When various newspapers collaborated to hold an extensive contest for “Miss Brazil” in 1929, the results were an extension of this eugenic ideology. Although the editors of these newspapers claimed that Brazilian beauty would reflect the country’s racial diversity, they effectively barred nonwhite women from participating. Susan Besse points out that in contrast to the image of the “sexy mulata” that followed in later decades, descriptions and images of 1920s beauty contestants sanitized them as “virtuous virgin/mothers” whose sexuality was limited to reproducing a eugenically superior nation (Reference BesseBesse 2005, 103).Footnote 8

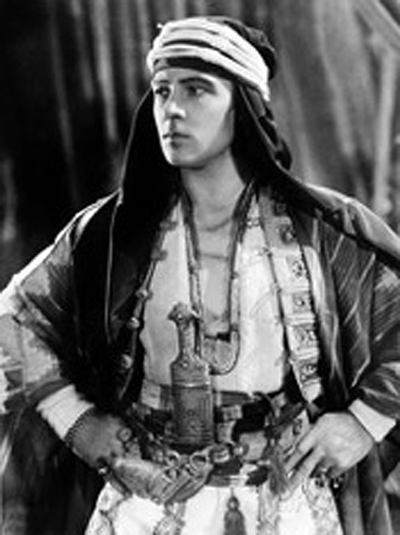

Yet, for all the medical discourse of eugenics that informed elite notions of whiteness and beauty, the 1920s was also the decade of modern girls, jazz bands, Josephine Baker, the Charleston, and of course, the rise of Hollywood in both the US and Brazil (Reference SeigelSeigel 2010). While Hollywood studios reflected and projected a culture of white supremacy, confining African American actors to demeaning and pejorative roles, the industry also participated in the primitivist and orientalist aesthetic that was in vogue in Europe and the Americas.Footnote 9 Through a combination of typecasting and carefully managing publicity, Hollywood studios developed a star system that categorized actors in specifically gendered, raced, and sexualized ways. For example, some actresses played the ethnically “other” and sexually aggressive “vamp,” whereas others epitomized the white, innocent, “girl-woman” (Reference DyerDyer 1998; Reference StaigerStaiger 1995; Reference StudlarStudlar 2013).Footnote 10 Rudolph Valentino, an actor of Italian descent, was the most famous example of the “Latin lover,” the sexually aggressive, vaguely Southern European or Latin American antihero (Reference StudlarStudlar 1996; Reference BergBerg 2002; Reference RodríguezRodríguez 2004). By 1926, Valentino’s popularity was waning, but on August 23, he passed away suddenly, just a week before the beauty contest began. Fox Film did not plan the contest in response to his untimely death, but the studio might have reaped additional publicity in their quest to crown a new Latin lover.

These Hollywood images percolated throughout Brazil, contributing to a robust film culture. Although Brazilian film companies were present in various regions around the country, and the production of newsreels and documentaries was prolific, Hollywood dominated over 80 percent of the Brazilian film market (Reference JohnsonJohnson 1987, 34).Footnote 11 Brazil was the second-largest market for Hollywood films in Latin America (Reference VaseyVasey 1997).Footnote 12 In addition, intellectual production related to cinema thrived across a variety of print outlets. Daily newspapers and weekly magazines reported on the premieres of the latest Hollywood gossip and films. A vanguard of film intellectuals formed “cine-clubs” and published magazines dedicated to the appreciation of cinema (Reference XavierXavier 1978).

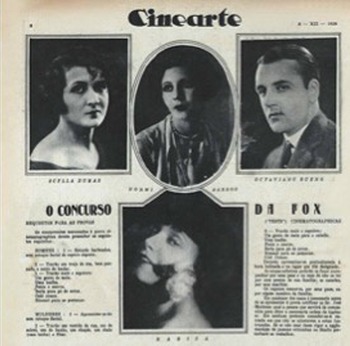

The contributing authors of the Brazilian film magazine Cinearte influenced film production and criticism for decades. Founded in 1926, Cinearte had a national circulation in the tens of thousands (Reference LucasLucas 2005, 68), and its authors aggressively advanced a nationalist agenda. For them, cinema was a means to attain the trappings of modernity and whiteness, and they exalted these ideals in language inflected with eugenic ideology (Reference Gomes and EmilioSalles Gomes 1974, 310; Reference XavierXavier 1978, 173; Reference BicalhoBicalho 1993, 24–25; Reference SchvarzmanSchvarzman 2003, 34–35). The domestic production of high-quality films would demonstrate Brazilian mastery of modern technology and taste. By excluding actors of color, films could also be a means of exhibiting Brazilians as a white rather than a mixed-race population (Reference StamStam 1997, 63, 66).Footnote 13 Productions did not always conform to these standards, and images of “naked Indians,” mixed-race actresses, and actors in blackface appeared in documentaries and feature films that Cinearte rejected in scathing reviews. Cinearte willfully aggrandized the production of Brazilian films but, in the absence of consistent domestic production, devoted most of its content to news from Hollywood. Although earlier film scholarship characterized Cinearte as evidence of Hollywood’s cultural imperialism in Brazil, more recent scholarship has recognized the magazine as a site for intellectual production and the development of a highly nationalist discourse on cinema and moviegoing.Footnote 14

Although the term photogenie originated in French film theory, Cinearte popularized the hybrid Portuguese-English term “photogenia” as a type of photogenic quality, an “aptitude for cinema” that connoted Hollywood luxury, beauty, hygiene, and whiteness (Reference XavierXavier 1978, 179).Footnote 15 However, photogenia also reflected Hollywood’s penchant for orientalism and sexual allure. A year before the Fox Film contest, the writer Maria Eugenia Celso published a short story titled “Photogenica” in one of Rio de Janeiro’s weekly leisure magazines. In the story, a “photogenic” woman proves her aptitude for the screen by studiously mimicking the expressions and gestures of Hollywood stars. She claims Hollywood as her “fatherland” and plans to become rich and famous in “roles of luxury, seduction, and drama … roles that will free me to develop my powers of fascination. I want to become a vamp.” Calling herself the next “Nita Naldi,” a Hollywood actress known for her exotic vamp roles, she laughs as she literally stuns a passerby with her sexual allure. At the end of the story, she offers the most “yankee of shake-hands” and saunters away “vamp-iricamente.”Footnote 16 Celso poked fun at Brazilian’s fascination with Hollywood, and in particular, women’s obsession with becoming starlets.

Celso’s use of “photogenia” also signifies an exotic sexual allure that one could cultivate and perform. Through photogenia, the woman in the story finds a sexually and racially liberating form of beauty. She aspires not to be the sanitized virgin/mother, the idealized feminine figure of eugenic whiteness. On the contrary, she seeks to be the vamp, Hollywood’s exotic and dangerous “bad woman.” Of course, photogenia was racially liberating to a very limited extent. Brazilian racist ideology negatively condemned women of color and poor women as sexually licentious, even as these same women used the legal system to defend their honor (Reference CaulfieldCaulfield 2000). As seen throughout the contest, photogenia was a temporary performance, a privilege of those who otherwise conformed to the eugenic definition of white beauty. Through photogenia, white Brazilian actors and actresses could become vamps, “sportsmen,” modern girls, or even “white with Latin blood.”

White with Latin Blood

North Americans and Brazilians collaborated on various stages of the contest, and Fox Film’s parameters for beauty did not translate without adjustment in Brazil. To launch the contest, José Matienzo, the representative of Fox Film in Latin America, traveled to Argentina, Chile, and Brazil, where each country held its own national contest.Footnote 17 To enter, contestants submitted a filled-in form and a photograph measuring 15 × 18 centimeters. A “Brazilian jury” composed of artists and writers, mostly from Rio de Janeiro, selected five women and five men to do a camera test. Paul Ivano, a Brazilian who worked as a cameraman in Hollywood, flew into Rio de Janeiro to film these tests. The resulting footage was sent to New York, where an “American jury” led by William Fox and other studio executives made the final selections.Footnote 18 From the beginning, Brazilian film magazines and daily newspapers publicized and reported commentary on each stage of the contest.Footnote 19

One of the key points of contention between Hollywood and Brazil was their differing interpretations of the term “Latin,” a mutable term that varied across multiple national and historical contexts. Michel Gobat has explored how nineteenth-century elites in Spanish America adopted a “Latin American” identity to assert their whiteness. “Latin” linked the region to Europe rather than Spain, which elites perceived to be racially and economically decadent. Nineteenth-century Brazilian elites found little use for the term “Latin America” except in occasional reference to countries they perceived as successfully white, such as Argentina and Chile. By the early twentieth century, intellectuals in Spanish America imagined Latin American as an identity associated with mestizaje rather than whiteness (Reference GobatGobat 2013). However, Hollywood in this same time period used the term “Latin” in a different way, as a racialized category that was vaguely tied geographically to Southern Europe or Latin America, but also signified an exotic type of aggressive sexuality.

Fox Film explicitly sought beauty contestants who were “white with Latin blood,” that is, people with white faces and bodies but with an inherent, biological characteristic of Latinness in the “blood.” Fox Film’s first press release about the contest referenced the need to “extend opportunities to other Latin countries” and to incorporate “new physiognomies and bright ideas” in their films.”Footnote 20 Fox Film’s definition of the physical parameters of “white with Latin blood” meant women who were sixteen to twenty-three years old, 1.5 to 1.7 meters tall, forty to fifty-five kilos, and in addition, had, “eyes that are dark when photographed.” Male contestants had to be no older than twenty-eight, taller than 1.75 meters, with “a robust complexion and upbeat physical appearance; eyes that are dark when photographed.” These physical measurements were not suggestions but “necessary requirements.” On the attached form that the applicant was to clip and fill out, there were spaces to list name, address, age, marital status, height, weight, color and length of hair, and color of eyes. The form lacked any space to write in one’s skin tone or complexion. Given the “requirement” that contestants be “white,” and the racial politics of both Brazil and Hollywood, this omission likely signified that fair skin was a nonnegotiable attribute. Fox Film therefore propagated specific, racialized characteristics as markers of both beauty and Latinness. The Fox Film Beauty Contest also emphasized standards of gendered propriety. Women who entered as minors had to have the permission of their fathers, and married women, the permission of their husbands.Footnote 21

The first advertisement for the contest in the Brazilian film magazine A Scena Muda announced that Fox Film, “convinced of the necessity of varying its casts and, having noticed their success of Latin types not only in the US but in the rest of the world, has resolved to find new stars in the countries most representative of South America: Brazil, Argentina, and Chile.”Footnote 22 In selecting these countries, Fox Film focused on its largest markets in South America but also limited the contest to regions with large populations of European-descendent peoples. For Fox Film, the “Latin race” was geographically fixed and best represented by these three countries.

While Fox Film’s emphasis on European descent pointedly excluded indigenous, Afro-descendent, and nonwhite populations, the idea of Latin blood connoted the exotic sexuality exhibited by Latin lovers like Rudolph Valentino. While Valentino was white enough to be represented in on-screen romances with nonethnic white actresses, Gaylyn Studlar has detailed the ways in which film studios cultivated Valentino’s public image of ethnic nonwhiteness. Male moviegoers in the United States used explicitly xenophobic language to voice their disapproval of his exotic sexuality as non-heteronormative and racially “other” (Reference StudlarStudlar 1996). When Fox Films asked for contestants to be “white with Latin blood,” they did not seek the eugenic, sanitized, chaste ideal of whiteness but rather the exotic and foreign Latin lover.

Brazilian commenters on the Fox Film contest infused national parameters of beauty into the transnational contest. Similar to other national beauty contests at the time, Brazilian writers claimed that the contest was racially inclusive but excluded anyone nonwhite. One advertisement for the contest in Cinearte asked, “Who will be the girl and boy that luck will take to the studios of Hollywood? From where will they come? From Rio de Janeiro? From São Paulo? From the states of the center, of the north, or the South? Will they be poor or rich?”Footnote 23 The underlying insinuation was that beauty could come from all reaches of a diverse Brazil, subtly hinting at stereotypes of regional difference.Footnote 24 Moreover, contestants could be “poor or rich,” emphasizing the seemingly egalitarian nature of the contest and of photogenic beauty. According to film scholar Isabella Goulart, although photogenia was supposed to be an “irrefutable quality” or a mysterious type of indefinable charm, it was actually contained within specific class, ethnic, and racial categories. For this reason, the Fox Films contest was limited to a tiny minority of wealthy, white, elite Brazilians (Reference GoulartGoulart 2013, 35–36).

Brazilian film intellectuals however, did not reject Hollywood’s demands for contestants to be “Latin” or to exhibit exotic sexuality. In early publicity campaigns, the Brazilian press emphasized the appeal of exotic sexuality, stressing that photogenia was distinct from conventional, eugenic notions of beauty. When one anonymous reader inquired about the contest, an editor responded, “My dear, there are ugly artists that are beautiful in photographs. It is a question of being photogenic.”Footnote 25 For Cinearte, the successful candidate had to have “something else”: “Let’s hope they choose the five girls [moças] and boys [rapazes] who are truly the most photogenic, and as they intend to be stars and idols, the girls and boys who respectively have the most ‘something different’ and the most ‘sex attraction.’” There was a gendered distinction in that photogenic women should have “something different” while men had more outright “sex attraction.” However, both qualities referred to the sexual desirability of “Latin” types. A Scena Muda echoed similar sentiments: “Among the applicants, there are not just beautiful ones, but sweet ones, attractive ones [insinuantes], seductive ones, in such a way that we can affirm that, at the very least, one young man and woman will go to Hollywood and elevate the name of Brazil in “Cinelandia” at the same time that they will smile upon fame, glory, and fortune.”Footnote 26 Although Fox Films had stipulated rigid physical parameters for beauty, the Brazilian descriptions of the successful candidate emphasized the need to conform to expectations of the exotic, to provide “something different.”

While “Latin blood” signified the sensuality of the Latin lover, having “white skin” could also be racially ambiguous. In the case of early Hollywood film, even light-skinned actors wore heavy white makeup, which was an aesthetic and functional norm. Clara Rodríguez (Reference Rodríguez2004) argues that the high contrast of black and white films allowed for “Latin” actors with darker skin to appear lighter and Gwendolyn Foster (Reference Foster2012) depicts “whiteface” makeup as a normative, sanitized identity devoid of ethnicity. Actors also used white powder to convey ethnicity and exotic foreign identities in Hollywood. In his star-making turn as a Middle Eastern “sheik,” Valentino wore thick, white pancake makeup. In fact, the use of white face powder became a significant mark of not only his ethnic otherness but of a feminized sexuality. An infamous editorial in the Chicago Tribune associated Valentino with “pink powder” and accused him of being too feminine because of the face powder and elaborate costumes he used to portray Middle Eastern, French, and Argentine characters (Reference StudlarStudlar 1989, 18).

In this time period, the use of white face powder did not necessarily mean that one was trying to whiten or to pass as white. Phenotype and skin color were important markers of racial identity in early twentieth-century Brazil and, even in contemporary society, remain consistent indicators of socioeconomic outcomes.Footnote 27 However, in an era of mass European immigration and nativist xenophobia, white skin was not an absolute sign of whiteness. In addition, writers and advertisers in women’s magazines idealized a particular type of white skin: a “clear” complexion with rosy cheeks. This beauty standard obviously excluded anyone with dark skin. Yet, hygienists also criticized an overly “pallid” complexion as a sign of poor health and one’s lack of fresh air. Intellectuals criticized white powder as “theatrical” and incapable of creating this rosy white glow (Reference SchpunSchpun 1999, 116–118).

A Brazilian sponsor of the Fox Film Beauty Contest explicitly capitalized on the association between white face powder and a theatrical, orientalized look. The Mendel Perfumery pledged prize money to the female winner of the contest (though not to the male winner, even if male actors wore white powder too) and in weekly advertisements, encouraged contestants to use their products. “Before posing for this important contest, improve the attractiveness of your face using: ‘Revelations of the Harem’ Rice Face Powder which will whiten your skin, beautifying it, without any trace of having used artifice.”Footnote 28 Goulart points out that the Mendel Perfumery emphasized that their makeup hid dark skin in a “natural” process of whitening, reflecting the contradictory expectations that women cultivate beauty but also be “naturally” beautiful (Reference GoulartGoulart 2013, 78; Reference SchpunSchpun 1999, 82). However, Mendel Perfumery named their rice powder “Revelations of the Harem,” an allusion to Hollywood’s imagined Middle East and its perceived illicit sexuality. Thus, Brazilians using white face powder may not have been necessarily “whitening” themselves but “othering” themselves by using an orientalized product that explicitly recalled imagined, Middle Eastern harems. In her study of beauty contests in 1930s South Africa, Lynn Thomas (Reference Thomas2006) argues that black women’s use of white face powder was not necessarily a form of whitening. Rather, some used white powder to signal their appropriate use of a modern, global commodity. Similarly, dark-skinned Brazilian contestants may have appropriated the multiple meanings of a “Revelations of the Harem” Rice Face Powder as a cosmetic that would make their skin whiter and thus more “appropriate” for the camera, but also as suggestive of Hollywood’s desired orientalist aesthetic.

“White with Latin blood” was a contentious and unstable term that had variable meanings according to Fox and to Cinearte. Although Fox Film explicitly called for “white” contestants who could conform to exact standards of height, weight, and coloring, the caveat of “Latin blood” signified that they were not seeking “whiteness” but in fact wanted stars who would exhibit an exotic sexuality. Fox Films essentialized this category in terms of region, imagining that a contest held in Argentina, Chile, and Brazil would necessarily yield this particular “physiognomy.” Brazilian commentators did not ignore Hollywood’s call for racialized sexuality and, in the early stages of the contest, emphasized the need for “sex-appeal” and “sex-attraction.” In the context of eugenics, which associated whiteness with chastity and hygiene, both Hollywood and Brazil understood “white with Latin blood” as exhibiting nonwhite sexual appeal. The Fox Film Beauty Contest thus offered Brazilians an alternative concept of beauty distinct from the sanitized “virgin/mother” represented by Miss Brazil. Yet this alternative standard of beauty did not destabilize Brazil’s racial hierarchies. As evidenced by the subsequent events of the contest, Brazilian intellectuals and many contestants only accepted “Latinness” and photogenia as temporary performances. On the pages of Cinearte, only white artists had the privilege to cultivate this sexualized allure.

Exhibiting Photogenia

The men and women who entered the contest demonstrated diverse interpretations of what “white with Latin blood” and “photogenic” meant to them. Some contestants adhered to the eugenic definition of whiteness, taking care to ensure that they fit within the biological parameters of the contest. Others offered “something else” that would set them apart as being exotic and sexually alluring, as seen in “Marisa’s” seductive pose with a rose in her mouth (Figure 2). Neither Marisa nor the other contestants on the page made the final cut.

Figure 2 Photographs of various contestants printed in Cinearte, December 8, 1926, 8. Acervo Biblioteca Jenny Klabin Segall/Museu Lasar Segall/IBRAM/MinC.

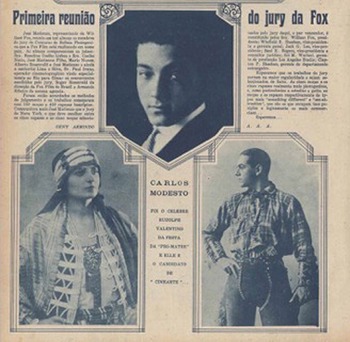

The contestant Carlos Modesto, whom Cinearte endorsed as their pick to win the contest, exhibited multiple types of masculine beauty. He submitted one photo of himself as Rudolph Valentino’s character in Son of the Sheik (1926; Figure 3), one as a cowboy, and a headshot of himself in a suit (Figure 4). The two costumed photos represented contrasting images of East and West; on the left, the exotic, orientalized Middle Eastern sheik, and on the right, of an “all-American” cowboy. The contrast between the headshot, which focuses on Modesto’s face, and the costumed photos below, which focus on his body and clothing, create the illusion that the headshot at the top is the “real” Modesto, neutral without costume. Of course, all three are performances of identity, and the headshot of Modesto is as much a posed, constructed image of masculinity as the costumed photos below it. However, the arrangement of the triptych reassures viewers that underneath his costumes, either as sheik or cowboy, Modesto is supposed to be the suited individual at the top.

Figure 3 Rudolph Valentino in Son of the Sheik (United Artists, 1926).

Figure 4 “Carlos Modesto,” Cinearte, December 1, 1926, 10. Acervo Biblioteca Jenny Klabin Segall/Museu Lasar Segall/IBRAM/MinC.

Miriam Hansen has interpreted Rudolph Valentino’s outlandish costumes as a type of “male male impersonation,” in which the appearance of exaggerated, orientalized androgyny, and later, of hypermasculinity, destabilized binary categories of gender (Reference HansenHansen 1991, 265–268). Given the contest’s very public rules for appropriately racialized and gendered bodies, Modesto’s performance is not destabilizing in the same sense. In contrast to Judith Butler’s (Reference Butler2006) theorization of drag, which exposes the artifice of gender performance, or Homi Bhabha’s (Reference Bhabha2004) concept of mimicry, which destabilizes the colonizer’s identity, Ann McClintock uses the term “cross-dressing” to refer to various types of gender, racial, and class performances. McClintock cautions that not all forms of crossdressing are subversive, but that, “privileged groups can, on occasion, display their privilege precisely by the extravagant display of the right to ambiguity” (Reference McClintockMcClintock 2013, 68). In the case of the Fox Film Beauty Contest in Brazil, contestants needed to adhere to rigid standards of height, weight, and skin tone in order to be eligible. By meeting these standards, Carlos Modesto proved his whiteness for the purposes of the contest (regardless of his racial identity in other contexts), and was thus free to display his “right to ambiguity” on the pages of Cinearte. The contrast between the outlandish costumes and the suited headshot undergirded rather than destabilized his identity as heteronormative and white.

Modesto wore heavy eyeliner and the racially and gender-ambiguous costume of “The Sheik,” but this was clearly an orientalist fantasy.Footnote 29 In fact, the caption stipulated that Modesto costumed himself not for the contest but for a “Pro-Matre festival.” Pro-Matre was a maternalist organization founded in 1918 in Rio de Janeiro, part of a larger wave of charitable organizations focused on maternal and infant health care. Through public festivals, galas, and parties, organizations like Pro-Matre occasionally provided an avenue for elite women and men to perform in theatrical plays and march in fashion shows—activities made permissible by their philanthropic aims.Footnote 30 Modesto’s affiliation with an elite philanthropic organization like Pro-Matre was evidence of his high social and moral status. In openly referring to Pro-Matre, the Cinearte article justified Modesto’s appearance as an androgynous, exotic identity by contextualizing it within the confines of respectable elite charity.

Other contestants who submitted applications and letters demonstrate the various ways in which they interpreted the parameters of “photogenia.” Olyria Salgado, an actress from Pernambuco who starred in A filha do advogado (The Lawyer’s Daughter) in 1926, filled out only the standard form that appeared in Cinearte.Footnote 31 Providing her name, age, marital status, and measurements, she demonstrated the requirements for a “photogenic” body: one meter and fifty-five centimeters, forty-eight kilos. She also wrote that she had very dark brown eyes and black, “demigarconne” hair, the short bob cut distinctive to the figure of the 1920s “modern girl.”Footnote 32 In contrast to Salgado’s concise application, Diogenes Leite Penteado, an actor who used the stage name “Diogenes Nioac,” wrote an eight-page letter addressed to Pedro Lima. He first described himself as having a “white complexion” (tez branco), with brown hair and brown eyes, 1.8 meters tall and weighing eighty kilos. In addition to this, he claimed that he had trained in all sports, including boxing, and lately had been doing fifteen minutes of “Swedish exercises” morning and night. Through these physical characteristics and exercises, he justified his approximation of Fox Film’s definition of male photogenic beauty, including a “robust” and “athletic” body and complexion. In addition, his lengthy letter was a mini-autobiography explaining how he chose his stage name, the necessity of creating a national cinema in Brazil, and funny anecdotes about his film career, including when another actress slapped him multiple times to rehearse for a film.Footnote 33

Although Olyria Salgado’s photogenia was expressed through her body, in her measurements and her appearance, Nioac expressed photogenia as a broader concept that included his stature and skin color, charisma, and funny anecdotes. He was photogenic because he not only looked but behaved like a Hollywood star, and his application letter mimicked the carefully crafted publicity materials and interviews that Hollywood studios developed for their actors. Nioac cultivated photogenia by training his body with Swedish exercises and his personality with practiced charm.

Forgetting Photogenia

In the months and weeks leading up to the announcement of the winners, Cinearte reported the anticipation surrounding the contest. “José Matienzo … lives each day called to the phone by beautiful feminine voices. Every husband that can’t find his wife says it’s because of the contest and threatens to come find him.”Footnote 34 However, after months of hype, the Brazilian press deemed the contest a disappointing failure. On February 3, 1927, Cinearte printed the results of the camera test, from which the Brazilian jury was to choose the top five men and five women. To their “frustration,” the results of the contest did not meet expectations, and while they recommended three female finalists, “all of the men were judged to be inapt.” The jury attributed the failure of the contest to “an unjust stereotype against Cinema, which still exists in our midst.”Footnote 35 They insinuated that those who might have been more photogenic did not even apply to the contest because they thought cinema was beneath them. In the section “your questions answered,” one of the editors at Cinearte reiterated, “We know that there are many young men who are good types, but … they did not show up. … No, [instead] residents of the countryside were called. According to the photographs, this is who thought it was worth the trouble to apply. The contest was relatively weak, but you know that there is a stereotype against cinema.”Footnote 36 In the Brazilian magazine Selecta, critic Sergio Silva insinuated that some women avoided the Fox Film contest for fear of compromising their sexual honor (Reference GoulartGoulart 2013, 109).Footnote 37 For individuals who chose not to apply, even the temporary performance of nonwhite sexuality, or any public affiliation with cinema, presented a real offense to their notions of gendered and racial propriety. For those who did apply but were deemed “inapt,” we clearly see the limits of acceptable beauty and how the performance of photogenia was limited to an elite few.

The criticism of “residents of the countryside” contradicted the statements from the first phase of the contest, which assured that photogenic contestants could come from any of Brazil’s diverse regions. In stating that only “residents of the countryside” troubled themselves to apply, the editor was not referring to wealthy rural elites. He was more likely referring to negative stereotypes of a nonurban, unsophisticated, and racially degenerate population, personified in the caricature of “Jeca Tatu.” A cartoon figure created by Brazilian children’s writer Monteiro Lobato in the 1910s, Jeca Tatu was a cautionary tale of how laziness, poverty, and bad hygiene would cause a racially degenerate and “ugly” population (Reference JarrínJarrín 2017).Footnote 38

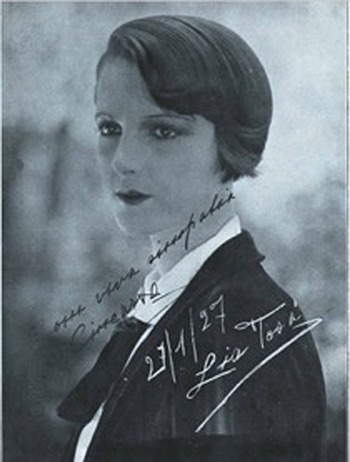

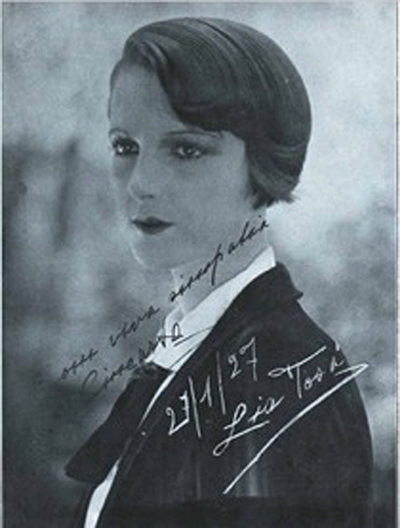

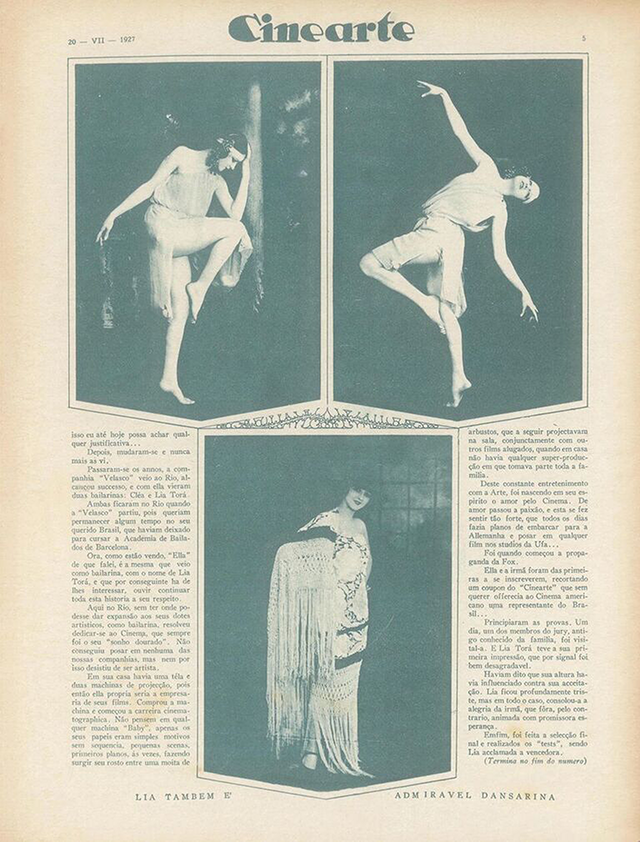

By April 1927, rumors swirled that none of the finalists selected by the Brazilian jury were considered photogenic enough by the North American jury. Cinearte disputed this as not having the “slightest bit of truth” and urged greater patience for results. Finally, in July 1927, Cinearte announced that the New York jury had selected Lia Torá and Olympio Guilherme as the female and male winners. At this point, Cinearte chose not to remind readers that the Brazilian jury had previously declared all the male contestants to be “inapt.” Despite the language of advertisements that implied the potential winner could be from anywhere in Brazil, the winners hailed from two of Brazil’s wealthiest states, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Lia Torá was a native of Rio de Janeiro but spent much of her youth in Spain, where she danced in a ballet company. Guilherme was from an elite family of São Paulo and worked as a film journalist and correspondent for Cinearte.

Brazilian film magazines represented both winners not as “white with Latin blood” but as white individuals who conformed to nationalist ideals of whiteness even as they displayed Hollywood’s photogenic sexual allure. Cinearte’s film critic Pedro Lima described Torá: “her type has whatever extraordinary thing it is that attracts … she has personality, she has ‘it,’ dear reader, but she also breathes innocence.” Lima claimed Torá had the “it” factor, which was broadly used in Hollywood media to describe a girlish type of sexual desirability, but he did not describe her as the sexually threatening and ethnically other “vamp” figure. Lima instead emphasized her “innocence” and how she knew to how to be “gentle” and “docile.”Footnote 39 Cinearte’s depiction of Lia Torá thus conformed to the magazine’s characterization of other Brazilian actresses like Nita Ney and Lelita Rosa. As Maria Fernanda Baptista Bicalho has shown, each of these actresses represented a mixture of innocence and seductiveness, a sexual allure tempered by moral respectability (Reference BicalhoBicalho 1993, 26–30). Even as the transnational dimensions of the Fox Film contest elevated Torá to a larger stage, Cinearte imposed its nationalist demands on Torá’s off-screen persona.

Like Carlos Modesto’s varied photos, Lia Torá appeared in multiple editions of Cinearte in different poses and costumes. When she was announced as the top finalist by the Brazilian jury, Cinearte published a cover photo of Torá wearing a black suit and bobbed hair (Figure 5). Her appearance, styled by the Brazilian Fox Film representatives in preparation for the New York–based jury, was almost an exact replica of Hollywood star Louise Brooks (Figure 6), known for her flapper roles. In both photographs, Torá and Brooks exhibited an androgynous look. While wearing bobbed hair, lipstick, and a masculine suit may have been acceptable for a camera test and the cover of Cinearte, the magazine otherwise described Torá as adhering to patriarchal standards of gendered propriety. Torá’s androgynous appearance recalled images of the liberated “new woman,” but according to the rules of the contest, she had to be accompanied by her father or husband to even participate in the camera test.

Figure 5 Lia Torá, female winner of the contest. Cinearte, February 2, 1927, 19. Acervo Biblioteca Jenny Klabin Segall/Museu Lasar Segall/IBRAM/MinC.

Figure 6 Portrait of Louise Brooks. Eugene Robert Richee, Core Collection, Biography Files, Margaret Herrick Library. Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences.

In a series of photographs that showed a more risqué appearance, Torá demonstrated her skills as a ballerina (Figure 7). She is scantily clad in the top photos and wears a fringed, vaguely Spanish ensemble in the bottom. In these images, Torá conformed to Hollywood’s demand for an exotic, sexually desirable Latin star. However, Cinearte couched these images, both literally and figuratively, in text that revealed this sexual desirability to be a façade. In the text that accompanied these images, the interviewer Pedro Lima presented Torá as a childlike ingenue. He infantilized her delight at “speaking Brazilian,” since she was accustomed to speaking Spanish, and praised her smile, “illuminated by two rows of teeth so white that they make her seem eternally childlike.”Footnote 40 Lima even diminished Torá’s intriguing admission that when she failed to secure acting roles in Brazilian productions, she sought to make her own films with a home recorder. Although Cinearte’s informal slogan was “every Brazilian film should be watched,” Lima deemed Torá’s foray into filmmaking to be little more than an amusing novelty, using diminutives to describe her films as “simple motifs without order, small scenes, close-ups, sometimes making her face emerge from a bundle of leaves.”Footnote 41 According to Lima, she projected her amateur films at home, surrounded by the safety and comfort of her family.

Figure 7 “Quem é Lia Torá?,” Cinearte, July 20, 1927, 5. Acervo Biblioteca Jenny Klabin Segall/Museu Lasar Segall/IBRAM/MinC.

In the interview, Torá seemed more like the “child-woman” Mary Pickford, the silent film star emblematic of “all-American” girlish innocence, than the sexually charged and ethnically other “vamp” (Reference StudlarStudlar 2013). While the photogenic woman in Celso’s story wielded her “sex-attraction” to make men into fools, Lima instead described Torá as exhibiting youthful innocence and moral purity. Torá was only twenty years old at the time, but she was a married mother of two. Yet, Lima focused on descriptions of her childhood home, her relationship with her father and sister, and did not mention her husband or children. Photos of Torá depicted her in an androgynous suit or in a revealing leotard, but Lima revealed that “underneath” these more risqué images, she was an innocent and chaste woman who stayed at home with her family. This “unveiling” of Torá, in an interview appropriately titled “Who Is Lia Torá?,” resembled the unveiling of Carlos Modesto during the earlier stages of the contest. Underneath their mutable identities, in their costumed performances, Modesto and Torá were both “white” individuals who did not threaten hierarchies of race or challenge eugenic notions of beauty.

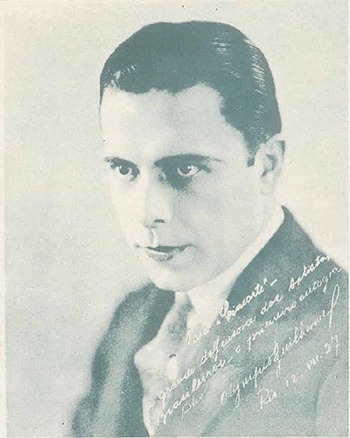

Cinearte referred to the male winner of the contest, Olympio Guilherme, as a heteronormative “good guy” rather than a sensual Latin lover. In photographs like the one in Figure 8, Guilherme wore a business suit, rather than the exotic costumes seen on Torá or the earlier contestant Carlos Modesto. The text of Guilherme’s interview focused on his athleticism: “He has every kind of physical equipment in his house. … He has legs with such developed muscles that nobody, even without knowing him well, could doubt that every morning he runs ten kilometers without stopping.”Footnote 42 Although, according to the article, Lia Torá thought Guilherme looked like Rudolph Valentino, Cinearte described him as more closely adhering to the “all-American” images of masculine sportsmen stars like Douglas Fairbanks and George O’Brien. The latter starred in action adventure films and westerns, epitomizing the strong American hero. Describing Olympio Guilherme’s work as a journalist, Lima described him in language inflected by eugenic discourse: “he has always been an indispensable part of the cultural campaign to benefit the moral sanitation of our country, just as we have done with Brazilian cinema.” For the writers of Cinearte, Olympio Guilherme was quite literally one of their own, a fellow supporter of the “physical and moral vigor of our race.”Footnote 43

Figure 8 “Olympio Guilherme: O homem que venceu o Concurso da Fox …,” Cinearte, July 20, 1927, 10. The autograph reads: “Para Todos – the great defender of Brazilian artists …” Acervo Biblioteca Jenny Klabin Segall/Museu Lasar Segall/IBRAM/MinC.

Guilherme was no moral hero, just as Torá was no ingenue, but Cinearte constructed these identities as the “real” personalities of the stars they sent to Hollywood.Footnote 44 When Fox Film launched the contest, they wanted to find their next “Latin” stars who would exhibit overt sexuality and push the boundaries of acceptable whiteness: women who were exotic, seductive vamps; men who were sensual and sexually aggressive but also feminized through costume, ethnicity, and celebrity. In contrast, Brazilian film intellectuals offered a different depiction of photogenia; their top stars might have the talent to exhibit “Latin blood,” but underneath, they conformed to Brazilian standards of gender, sexual propriety, and eugenic whiteness.

Epilogue

In August of 1927, Lia Torá and Olympio Guilherme headed to Hollywood, a journey that Cinearte chronicled as a triumphant arrival. Unfortunately, in contrast to “elevating the name of Brazil in Hollywood,” neither Torá nor Guilherme had successful careers. Torá starred in one feature-length film, A Veiled Woman (1929) before the growth of sound film ended her prospects at mainstream success. She continued to act in a handful of US Spanish-language films in the 1930s but never achieved the international fame that the contest had promised. Guilherme was less successful. After a few minor roles, he returned to Brazil embittered by his experience, a disappointment that he detailed in his fictionalized memoir Hollywood (1932) (Reference BorgeBorge 2007).Footnote 45

Just as the Fox Film Photogenic Contest was ending, the results of another Brazilian beauty contest were coming to fruition. In the same year of Torá’s and Guilherme’s departure to Los Angeles, four other aspiring Brazilian actors expressed their own desires to conquer Hollywood. Contracted by the short-lived Almeida Films in the state of Minas Gerais, the actors filled out questionnaires detailing their cinematic hopes and ambitions.Footnote 46 One of the actors, named D. Mosquera, had gained a film role by entering and winning the studio’s local beauty contest. Another actor, Luis Pimental, wrote that his professional goal was to “continue to be an artist and to become the rival of Jack Holt and Von Stroheim” (two Hollywood actors).Footnote 47 The one female actress of the group, Hilda Webber, wished to become a “star.” In response to the question of how she became an actress, she wrote, “simply by being photogenic.”Footnote 48

Webber, in fact, would not have met the “minimum requirements” for Latin beauty as Fox Films had defined the year before. Webber wrote that she had blond hair and blue eyes, so Hollywood would have rejected her as a dark, Latin beauty. Webber was also born in Estonia, and whether she was or not, she might have been stereotyped as Jewish because of her Eastern European origins.Footnote 49 Webber was too light to be Latin in Hollywood and too foreign to be a star in Brazil. Yet, in Webber’s own interpretation of photogenia, she had the “something else” that was required to be apt for the screen.

The questionnaires of Almeida Films are now ephemera. D. Mosquera, Luis Pimental, Hilda Webber—their names and images have not lasted beyond the limited life span of nitrate film. Although they never “elevated the name of Brazil” in Hollywood, they show how Brazilian actors still positioned themselves within a transnational film culture. They formulated their own ideas of beauty, fame, and cinematic potential in response to Hollywood images, but also in response to local beauty contests and film studios. The Fox Film contest, far from an isolated event, was a highly visible case study in how Brazilians interacted with a dynamic transnational film culture to construct ideas of race, gender, and sexuality.

Even as they chased Hollywood ideals of beauty and sexuality, Brazilian intellectuals and beauty contestants by no means accepted these ideals without adaptation. Far from victims of Hollywood cultural imperialism, Brazilians used this transnational moment to cultivate bodies and performances that exhibited Hollywood’s penchant for exotic sexuality while still buttressing elite Brazilians’ advocacy for white beauty. In the Fox Film Photogenic Beauty Contest, Hollywood solicited a racialized view of Latinness, geographically fixed in the Southern Cone and physically fixed “in the blood” and in white faces, healthy bodies, and dark eyes. However, Brazilian film intellectuals and contestants rejected this racialized definition and viewed “Latinness” as more mutable. Rather than inherent “in the blood,” the exotic sexuality associated with “Latinness” was part of the performances, costumes, and gestures that Brazilians cultivated through photogenia. Ultimately, Brazilian film critics decided that the winners of the Fox Film contest should adhere to gendered ideals of whiteness, with Lia Torá exhibiting sexual innocence and purity and Olympio Guilherme, an image of robust male athleticism. Despite the search for contestants with “Latin blood,” the winners did not challenge but rather exposed the centrality of whiteness to Brazilian eugenic standards of beauty. Beyond Torá and Guilherme, multiple aspiring individuals “failed” in their quest for stardom by having bodies and faces deemed inappropriate. Yet, failed beauty contestants and obscure aspiring actors demonstrated their own interpretations and performances of photogenic beauty, in hopes of conquering Hollywood.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Alvaro Jarrín, Isabella Goulart, Leonardo Marques, and Rielle Navitski, who made suggestions at various stages in the development of this article. Additional thanks to the anonymous readers at the Latin American Research Review for their constructive comments.