A substantial body of research indicates that, for people from Black and AsianFootnote 1 ethnic minorities, access to, utilisation of and treatments prescribed by mental health services differ from those for White people (Reference Lloyd and MoodleyLloyd & Moodley, 1992; for a review see Reference BhuiBhui, 1997). Pathways to mental health care are important, and the widely varying pathways taken in various societies may reflect many factors: the attractiveness and cultural appropriateness of services; attitudes towards services; previous experiences; and culturally defined lay referral systems (Reference Goldberg, Bhugra and BahlGoldberg, 1999). Contact with mental health care services may be imposed on the individual, but people who choose to engage with services usually do so only if they think that their changed state of functioning is health-related and potentially remediable through these services. In such cases, they will contact whoever they perceive to be the most appropriate carer, and these carers are often not part of a national health care network.

The pathway to care approach focuses on the point of access to care and the integration of care by culturally diverse carers. For example, if for African–Caribbean men in crisis the most common point of access to mental health services is through the police and the criminal justice systems rather than through their general practitioner (GP), then the challenge is to explore the reasons for this at the interface of these agencies. Carers include the popular and folk sectors of health care provision as well as standard primary and secondary care services and the voluntary sector. Once the range of perceived carers for a cultural group is known, these can be considered as potential sites of case identification and intervention.

The development of a model for Black and Asian ethnic minorities requires that these other access points be taken into consideration.

Goldberg & Huxley's model

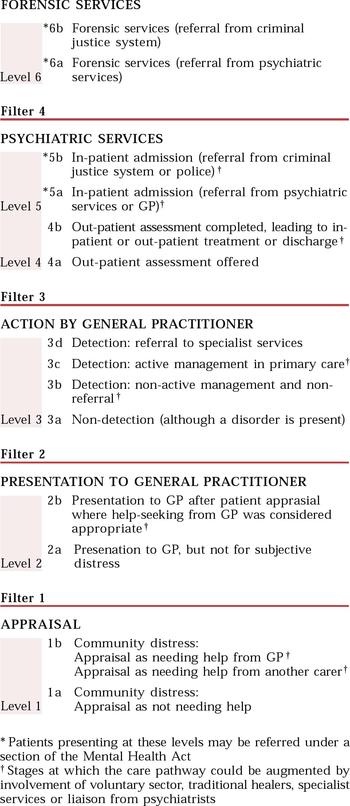

Goldberg & Huxley (1980) described different levels of engagement with health care within community, primary and in-patient services. To reach specialist care a patient needs to pass through a series of referral filters. This model has been extremely useful, not only in understanding epidemiological findings and pathways into psychiatric care, but also as the starting point for evaluating the needs of patients with mental illness.

Although services have continued to evolve, the model has only recently been modified. Commander et al (1997) added a Mental Health Act level. Moodley & Perkins (1991) explored routes to care, trying to conceptualise the pathways taken by African–Caribbean people admitted to in-patient care and finding that the police and accident and emergency departments are important. The model shown in Fig. 1 is based on Goldberg & Huxley's original, but it includes several additional stages to reflect the appraisal, expression and presentation of distress in primary care, as well as the appraisal of community distress. It also shows the stages at which the care pathway could be strengthened by the involvement of the voluntary sector, traditional healers, specialist services or liaison from psychiatrists.

The research data that we cite relating to the experiences of patients from ethnic minorities of the care pathway are limited by the focus of the studies cited, which included mainly in-patient and psychiatric services and some primary care sites.

Community-level distress and the lay referral system

Different societies have different patterns of help-seeking, and some countries involve traditional healers in their health care systems (Reference Goldberg, Bhugra and BahlGoldberg, 1999). Indeed, Kleinman (1980) has described folk and popular sectors of health care as dominant in most societies. It might be imagined that similar patterns would emerge in immigrant communities in the UK, subject to the availability of alternative healers and the persistence of traditional pre-immigration health beliefs and illness behaviour. However, mental health professionals attend to their significance infrequently and such domains are rarely researched.

Gray (1999) has argued that the voluntary sector is the most appropriate and least stigmatising source of help for Black patients, but the voluntary sector rarely figures in the strategic development of mental health services for Black and Asian patients in the UK. The inclusion of the voluntary sector in the pathway model, together with health promotion, schools, places of worship and traditional healers, leads to a more complex but comprehensive model, matching more closely the help-seeking narratives of Black and Asian people. Another variable that is often ignored within this model is the influence of the gender of individuals on help-seeking.

Research data

Access to and use of services from community-level distress

-

• Cole et al (1995) demonstrated that for first-episode psychosis in the London borough of Haringey, compulsory admission, admission under section 136 of the Mental health Act 1983, first contact with services other than health, and no GP involvement were each associated with being single rather than with ethnic group. Also, compulsory admission, admission under section 136 and police rather than GP involvement were associated with not having a supportive friend or relative. Compulsory admission was also associated with having a family of origin living outside of London.

-

• Koffman et al (1997) found that more Black patients admitted to wards were not registered with a GP than in the non-Black comparison group.

-

• Harrison et al (1988) records that 40% of African–Caribbeans made contact with some helping agency in the week preceding admission, compared with 2% of the general population.

Primary care consultation rates

-

• Gillam et al (1989) studied the patterns of consultation in seven general practices in the London borough of Brent. Male Asians had substantially higher standardised patient consultation ratios than did other ethnic groups. Consultations for anxiety and depression were lower in all immigrant groups (72–76% of the rate for the White comparison group). White British patients more often left the surgery with a repeat appointment, prescription or sickness certificate.

-

• Kiev (1965) reported a higher overall consultation rate among Black (Jamaican) primary care attendees in Brixton, south London. The rate of psychiatric disorder was also higher than among the White British population. West Indians were more likely than White British patients to seek help from alternative and traditional sources.

-

• Lloyd & St Louis (1996) interviewed a sample of Black women primary care attendees and compared them with a matched sample of White British attendees in south London. They reported that Black women were less likely to know what they wanted from their GP (25% of the White rate), to make multiple requests of their GP (23% of the White rate) and to leave a primary care consultation without a follow-up appointment. During the follow-up year, none of the White patients self-referred to accident and emergency departments, but 5% of the Black patients did so. Black African women consulted their GP less frequently than other women. Black patients were less satisfied with the consultation than White patients; especially Black African women, who also were the most distressed and attended the least often.

Primary care: presentation, detection and referral to specialist services

Asians are known to present frequently in primary care, but not with mental disorder (Reference Gillam, Jarman and WhiteGillam et al, 1989). Even if they do not present with physical symptoms a significant proportion are still liable to be given a physical diagnosis (Reference Wilson and MacCarthyWilson & MacCarthy, 1994). Commander et al (1997) report that Black patients are the least likely to be recognised as having mental disorder in primary care (White patients are the most likely) and the most likely to be referred to specialist services if mental disorders are detected (Asians are the least likely to be referred). However, the findings are not consistent. Comparison of African–Caribbean and White patients by Shaw et al (1999) suggests that, for common mental disorders, there were few differences in detection.

It is likely that variations in local service configurations and professional practice influence detection rates as much as do the cultural origins of the patient. Asian GPs are reported to be poorer detectors of morbidity among Asian patients (Reference Odell, Surtees and WainwrightOdell et al, 1997). Difficulties of assessment by Asian GPs may not be restricted to Asian patients (Reference Bhui, Bhugra and GoldbergBhui et al, 2001) and may reflect the fact that the cultural views of practitioners can influence the assessment and clinical management of mental disorders (Reference Patel, Bhui and OlajidePatel, 1999). The health professional's own explanatory model of illness and its influence on his or her practice have not received adequate attention. It is widely assumed that the uniformity of medical training across different cultures leads to uniformity of skills and values regarding illness. However, in the area of mental illness there is more variation of explanatory models than might be the case with disorders that have demonstrable physical pathologies and abnormalities. However, this explanation alone does not account for the variation in clinical management of different ethnic groups consulting the same pool of GPs. Furthermore, patients' cultural appraisal of their problems, and perhaps their preferred interventions, may differ from those of their primary care physicians, irrespective of the cultural origins of either the professionals or the patients.

Research data

Detection and referral of psychiatric morbidity

-

• Responses on the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) recorded by Lloyd & St Louis (1996) in their south London study showed no differences between Black and White women, although within the Black group Black African women had higher scores. There were differences between scores on the Clinical Interview Schedule: GPs noted psychiatric problems in 26% of Black women and 34% of White women, all of whom had scored as cases on the GHQ.

-

• Li et al (1994) report that in Tower Hamlets (east London), 2.2% of all attendees had needs that could not be met within the district services, and that the rate of detection of conspicuous morbidity in Black patients was almost half that for White patients.

-

• Burnett et al (1999) reported that African–Caribbean people with schizophrenia were less likely than White people to have had a GP referral to mental health services.

-

• Bhui et al (2001) report that no differences were found in rates of detection of common mental disorders by Asian GPs in Punjabi Asian and White English patients.

Assessment and admission in general adult services

Several authors have agreed that Black people are overrepresented in psychiatric hospitals and that their need for psychiatric help is revealed through crisis services and the Mental Health Act more often than for their White counterparts (Reference BhuiBhui, 1997). For example, Davies et al (1996) found that Mental Health Act detention for assessment and treatment was more common among Black and Asian ethnic minorities. This applied to all diagnoses and prevalent cases of psychosis. However, ethnic origin is not the only factor. For example, Black women in Hammersmith and Fulham (west London) are reported to have lower compulsory admission rates than White women, whereas in Southwark (south-east London), Black women have higher rates (Reference Bebbington, Feeney and FlanniganBebbington et al, 1991).

Falkowski et al (1990) showed that Black people were overrepresented among detained absconders from in-patient units. Although Black people often find services unattractive, it is likely that detained patients are more likely to perceive them as unhelpful (Reference Parkman, Davies and LeeseParkman et al, 1997).

Several studies report that admission to in-patient and forensic care among Black patients more frequently follows referral from criminal justice agencies or the police. Moodley & Perkins (1991), however, report that routes into care for African–Caribbean people were not statistically significantly different from those for Whites. Cole et al (1995) have shown that admission through the police is more likely if the patient does not have a confidant or GP to support them, and that this is so of all cultural groups. The greater social isolation of those admitted with schizophrenia may explain their propensity to be admitted late, having failed to notice themselves to be ill.

These data suggest that stronger links with the police, courts and prisons are required. All may assist in the diversion of those with mental illness, where this is appropriate, and especially where known patients have fallen out of care and are at risk of ending up in forensic institutions (Reference Bhui, Brown and HardieBhui et al, 1998; Reference Coid, Kahtan and GaultCoid et al, 2000). A rapid access point for families, so that crises can be addressed quickly, is also essential. A further focus of future analysis must be decision-making processes around formal assessments. These must include consideration of attractive, safe and clinically effective alternatives to in-patient admission.

Research data

Admission rates and cirumstances

-

• Studies in London have shown that Mental Health Act admission rates are higher for African–Caribbeans than for comparable samples of White and other ethnic groups (Reference BagleyBagley, 1971; Reference Bebbington, Feeney and FlanniganBebbington et al, 1991; Reference Moodley and PerkinsMoodley & Perkins, 1991; Reference Wessely, Castle and DerWessely et al, 1991; Reference King, Coker and LeaveyKing et al, 1994; Reference CallanCallan, 1996; Reference Davies, Thornicroft and LeaseDavies et al, 1996). The magnitude of the excess varies in different parts of the city and is likely to depend on both the population and the configuration of the local service (Reference Bebbington, Feeney and FlanniganBebbington et al, 1991).

-

• Rates of admission with schizophrenia and affective psychoses for African–Caribbeans are 3–13 times the rates for White patients (Reference Bebbington, Feeney and FlanniganBebbington et al, 1991; Reference Moodley and PerkinsMoodley & Perkins, 1991; Reference King, Coker and LeaveyKing et al, 1994; Reference van Os, Castle and Takeivan Os et al, 1996).

-

• Once admitted, young African–Caribbean patients were more likely to be readmitted. First admissions were more likely to be young men (under 30 years) (Reference GloverGlover, 1989).

-

• Davies et al (1996) scrutinised hospital and community contact data relating to all prevalent cases of psychosis in London and concluded that 70% of the Black Caribbean group, 69% of the Black African group and 50% of the White group had previously been detained under the provisions of the Mental Health Act.

-

• A study of the self-reported utilisation of acute in-patient and out-patient services recorded in the General Household Survey data aggregated between 1983 and 1987 revealed a higher rate of utilisation among young males of all ethnic groups, with a decline with increasing age, but an increase in old age (Reference Balarajan, Raleigh and YuenBalarajan et al, 1991).

-

• Callan (1996) reported that African–Caribbeans had shorter readmissions than a British-born White control group, and a milder course was hypothesised to exist among African–Caribbeans.

Forensic services

African–Caribbean men are known to be overrepresented in secure units, among remand populations and in sentenced prison populations. Coid et al (2000) showed that first admission rates to forensic units for half of England and Wales were 5.6 times higher among Black males than among White males; rates for Asian men were half those of White men. Black women's admission rates were 2.9 times higher than those of White women. Asian women had admission rates that were one-third those of White women. Patterns of offending and disposal by courts are known to vary by ethnic group (Reference Bhui, Brown and HardieBhui et al, 1998). One explanation is a lack of intervention by community mental health services early in the course of an illness (Reference Bhui, Brown and HardieBhui et al, 1998; Reference Coid, Kahtan and GaultCoid et al, 2000). Other possible explanations are that African–Caribbeans are actually more violent when they present with mental health problems, or that they are perceived to be so. Another explanation is non-recognition of signs of illness (by patient, family, GP or psychiatrist) until they are more severe.

The excess of contact with the criminal justice system can also result from the individual's dissatisfaction with mental health services (Reference Parkman, Davies and LeeseParkman et al, 1997), or the professional's appraisal of the distress as not needing treatment (Reference Moodley and PerkinsMoodley & Perkins, 1991). Another possible explanation is that Black people are not actively managed and retained in primary care services, so that if they become distressed and their distress is not understood it is labelled as ‘psychiatric’ and they are referred to specialist services (Reference Commander, Sashi Dharan and OdellCommander et al, 1997).

We must conclude that either African–Caribbean groups are no different in their presentation and the risks posed but that they are assessed to carry higher risks associated with distress, or that African–Caribbeans, when distressed and developing psychoses, do present with more violence.

Research data

Prevalence

-

• Among patients admitted to secure units in England and Wales, 20% were African–Caribbean (Reference Jones, Berry and EdwardsJones & Berry, 1986).

-

• Among sentenced prisoners, the prevalence of mental illness was 6% for African–Caribbeans and 2% for the White population (Reference Maden, Swinton and GunnMaden et al, 1992).

-

• In a sample of remanded mentally disordered offenders, 17.6% of White, 68.8% of Black Caribbean, 43.8% of Black African, 58.3% of Black British and 42.1% of other non-White ethnic groups had a diagnosis of schizophrenia (Reference Bhui, Brown and HardieBhui et al, 1998). Banerjee et al (1995) reported a higher prevalence of schizophrenia among Black remanded men who were transferred to hospitals. A survey examining decisions made about remanded people on the basis of psychiatric reports demonstrated that 37% of White defendants were granted bail and only 13% of the Black group (National Association for the Care and Resettlement of Offenders (NACRO), 1990).

-

• In certain areas of the UK, Black men are more likely to receive a custodial sentence than their White counterparts (NACRO, 1989). Black defendants received a smaller range of disposals after court appearance; three-quarters of Black defendants and half of White defendants have had previous contact with psychiatric services (NACRO, 1990).

Cultural variations in assessment

Non-recognition of mental illness by health care professionals may reflect a mismatch between the patient's cultural expression of distress and the signs and symptoms sought by the clinician as manifestations of particular diagnostic syndromes. For example, visual hallucinations reported to be more common among West African patients with schizophrenia (Reference Ndetei and VadherNdetei & Vadher, 1984).

Conversely, culturally sanctioned and acceptable distress experiences may attract pathological explanations from professionals. First-rank symptoms may not have the same diagnostic significance across cultures (Reference ChandrasenaChandrasena, 1987). What psychiatrists call ‘paranoid beliefs’ have culturally sanctioned value among African and West Indian groups, and the assignation of pathological significance to them may therefore be flawed (Reference Ndetei and VadherNdetei & Vadher, 1984). Paranoia and religious content to beliefs are more common among West Indians and West Africans (Reference Littlewood and LipsedgeLittlewood & Lipsedge, 1984; Reference Ndetei and VadherNdetei & Vadher, 1984).

The pathways approach focuses on service levels but it is professional practice that determines the outcome of consultations. Individual attitudes, professional skills and cultural awareness of norms are all influential on the passage through filters and in treatment decisions (Box 1).

Box 1 Good practice in assessment

Be aware of your own world view and that of your patients and their carers

Take into account patients' explanatory models of their illness

Assess patients' cultural appraisal of their problems

Be aware of racialism in yourself and your patients¤

A model of engagement for African–Caribbean patients

It seems that African–Caribbean groups are the least satisfied with secure services, but are the most liely to be held in them. Parkman et al (1997) demonstrated that young Black men's dissatisfaction with in-patient services was directly proportional to the amount of contact they had had with such services. They describe this as the ratchet effect of consecutive contacts. This, coupled with non-detection of disorders by GPs and difficulty in managing disorders in primary care settings, increases the likelihood that patients in crisis will come into contact non-health-related agencies (police or forensic services).

Geneal practitioners' diagnostic skills, knowledge about mental health, early management of mental illness and timely referral to hospital are all potential foci for primary care intervention.

Like all patients, African–Caribbean patients too may benefit from, and prefer, management in primary care settings. This may in part be because of the less stigmatising public attitudes towards primary care than towards psychiatric hospitals.

A pathway solution here might be to improve recognition rates and also to increase the skills mix of the primary care team to enable engagement with and active management of African–Caribbean people in primary care. Another solution might be to target educational campaigns and relapse prevention strategies at patients. Alternatively, the fundamental nature of services might be changed towards home-based care or early intervention (i.e. services delivered in public health settings rather than in psychiatric units). Such options may in themselves improve engagement, but GP surgeries and psychiatric clinics must take care to avoid the institutionalised attitudes and practices that can flourish in psychiatric hospital environments. Where competent risk assessment permits it, totally different management strategies involving family, neighbours or voluntary sector agencies might be considered as more culturally appropriate.

Partnerships between the primary care team and other pathway agencies

Bhugra et al (1997), in a study examining the incidence and outcome of schizophrenia, found that only 1 in 36 African–Caribbean patients with schizophrenia presented through their GPs. Health care systems are not organised in accordance with the preferred pattern of help-seeking, and do not readily lend themselves to early intervention. To ensure early intervention for African–Caribbean patients who develop a new mental illness or relapse, there needs to be close liaison between community mental health teams and primary care teams, with agreed priority being given to high-risk groups. Persistent states of distress in the absence of timely intervention can culminate in presentation in crisis, and presentation only when disorders are severe and patients' social networks and housing conditions are already compromised. Recovery times will then be longer and a greater intensity of input will be required to re-establish the necessary conditions for recovery and relapse prevention. If primary care teams were to become involved at an earlier stage, identifying symptoms of relapse and keeping contact with non-statutory agencies with which African–Caribbeans have regular contact, then this might enable early intervention. Furthermore, if culturally attractive services are identified as partners in care provision, the total package of care offered to Black and Asian ethnic minorities would be likely to be more attractive and to be more successful in engaging them in the long term (Box 2).

Box 2 Primary care and other agencies

The clinician must take the lead in identifying and maintaining liaison with primary care and other agencies

The consultation model should ensure regular liaison with the primary care team

Community mental health team (CMHT) members should be represented in the primary care consultation

Where appropriate, CMHTs and trusts should use ‘culture brokers’ (health workers trained to work with communities that have significant ethnic minority populations)

Psychiatrists should support and educate primary care teams to engage patients with special needs

Psychiatrists can play a lead role in education and liaison with partners in care, including GPs, housing workers, and voluntary agencies. Such an approach is especially useful if there is concern about unusual mental states. This assumes that psychiatrists are themselves confident that they can assess complex mental states in patients from Black and Asian ethnic minorities and that they recognise the limitations of their own skills and competencies.

Places of worship, leisure clubs, entertainment venues and culturally attractive independent services may all act as points of first contact. In a recent study, half of the Black users interviewed stated their belief that their treatment and diagnosis would (or might) have been different had they been in contact with a member of staff who understood their experiences as a Black person (a quarter felt that it would have made no difference) (Reference Robertson, Sathyamoorthy and FordRobertson et al, 2000).

Conclusions

Goldberg & Huxley's (1980) original model is no longer sufficiently comprehensive. It requires inclusion of a wider range of agencies. Yet, the exact numbers of people passing through each level are less well described. Future research should explore the levels that we have included and the ease or resistance with which people pass from one level to another. Passage through the filter should be seen as a dynamic two-way process, and alternatives to management in psychiatric environments should be encouraged wherever possible. It is likely that those with acute emergency presentations cannot be safely managed outside a skilled hospital environment. However, if hospitals are impoverished in terms of staffing, quality of décor, personal space and time to build therapeutic relationships, these will compound the distrust that already exists.

The cultural authenticity of the voluntary and independent sectors may be essential for an engaging service, and primary care teams might usefully liaise with these sectors to maximise the opportunity to manage patients without referral to specialist services.

The pathways approach offers a framework within which health service research, service development and the delivery of quality care may be organised.

Multiple choice questions

-

1. Goldberg & Huxley's model of pathways:

-

a has three levels

-

b can only be used for White patients

-

c sees GPs as gatekeepers

-

d used the concepts of filters

-

e can be modified to explain patients' pathways to forensic services.

-

-

2. Black patients:

-

a are overrepresented in psychiatric hospitals

-

b seek excess help in primary care

-

c always prefer alternative therapies

-

d are overrepresented in forensic units

-

e use voluntary organisations more frequently.

-

-

3. In primary care:

-

a Black women are less sure of what they want in the consultation

-

b Asian GPs are better detectors of psychiatric morbidity among Asian patients

-

c Asian patients are more likely to receive a physical diagnosis

-

d African–Caribbean patients are less likely to have follow-up appointments

-

e Asians present to general practice less frequently than Whites.

-

-

4. In forensic services:

-

a African–Caribbean males are underrepresented

-

b Asian males are overrepresented

-

c Black women are generally less likely than White women to be detained

-

d admissions of Black patients often follow referral from the criminal justice agencies

-

e court diversion schemes may improve the take- up rate.

-

-

5. Cultural variations of symptoms indicate that:

-

a visual hallucinations are more common in West African patients with schizophrenia

-

b paranoid beliefs are culturally sanctioned in some groups

-

c religious beliefs have cultural prominence in some groups

-

d first-rank symptoms of schizophrenia are not always pathognomonic

-

e innovative approaches may be indicated in management.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | T | a | T | a | F | a | T |

| b | F | b | F | b | F | b | F | b | F |

| c | T | c | F | c | T | c | F | c | T |

| d | T | d | T | d | T | d | T | d | T |

| e | T | e | T | e | F | e | T | e | F |

Fig. 1 Pathways to care: expansion of the Goldberg & Huxley (1980) model to address accessibility and service use for Black and Asian ethnic minorities

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.