1. Introduction

In the 1980s, the US Department of Commerce (USDOC) determined that, in Soviet-style nonmarket economies (NMEs), the agency could neither identify nor measure grants or subsidies. The reasoning was that subsidies to producers in an NME country were not countervailable within the meaning of the countervailing-duty statute because the purpose of the law was to offset the unfair competitive advantage that foreign producers receive from government subsidies. Yet, in an NME, the state itself owns or controls most businesses and assets. Consequently, to label government payments as ‘subsidies’ in such situations would mean that the NME government would be subsidizing itself.

In March 2007, the USDOC reversed this policy for evolved NMEs such as China and Vietnam. Since the policy change, the USDOC still treats both of these countries as NMEs for anti-dumping (AD) purposes, but it also identifies, measures, and countervails subsidies. In the last few years, the United States has imposed simultaneous anti-dumping duties (ADDs) and countervailing duties (CVDs) in more than 20 cases, all but one involving China.Footnote 1

In United States – Definitive Anti-Dumping and Countervailing Duties on Certain Products from China,Footnote 2 China challenged the United States's new policy and claimed the United States was ignoring its obligations under the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM Agreement). The headline-grabbing claim involved ‘double remedies’, sometimes referred to as ‘double counting’. In this claim, China argued that in various investigations the application of both ADDs and CVDs on the same products from China created a situation where the same instance(s) of subsidization was offset twice. The US made a two-fold rebuttal. First, the WTO distinguishes between export subsidies – where double remedies are presumed and where offsets are provided by the United States (in either market or nonmarket-economy situations) – and domestic subsidies − where no such analysis is required. In other words, the United States argued there was no legal basis for a double-remedies claim. Second, even if there were a basis for a claim, no evidence existed that such double remedies in fact were occurring.

The Panel, citing studies undertaken by the US Government and parallel US court decisions, rejected the latter argument and found that double counting was ‘likely’. However, the Panel agreed with the United States on the former and determined that the WTO Agreement did not prohibit the practice.Footnote 3

The WTO Appellate Body (AB) overturned the Panel on this second finding and found that Article 19.3 of the SCM Agreement did contain a requirement to not impose double remedies. However, in a missed opportunity the AB failed to recognize that the economic rationale for banning simultaneous AD and CVD for an export subsidy applies equally well to domestic subsidies when the United States's NME methodology is used to compute normal value. The AB only concluded that double remedies are ‘likely’ to occur and refrained from putting ‘likely’ into context. The AB recommended investigating authorities focus on the extent to which domestic subsidies have lowered the export price of a product (which according to the AB captures the impact of the domestic subsidies). Once the price impact is measured, the investigating authorities then need to take the necessary corrective steps to adjust for the double counting.

Our critique of the AB's decision is nuanced. On the one hand, due to particulars of US AD and CVD methods (discussed below), we believe the AB's determination misses the mark with respect to the specific cases and methods underlying this dispute. On the other hand, we believe the AB's measured position is more appropriate when the double-remedies issue is interpreted in the context of WTO NME rules.

While somewhat overshadowed by the double-remedies issue, we believe at least two other claims will likely have significant long-term consequences for the use of AD and CVD against China. One key question is what constitutes a ‘public body’. Given the nature of China's economy, this question will be relevant for most future CVD cases. The United States's position was that any entity controlled by a government via majority state ownership can be considered a ‘public body’. The AB found this interpretation too broad and instead determined that whether an entity is a ‘public body’ hinges on whether the entity is vested with or exercises ‘governmental authority’, a formulation that presumably envisages scenarios in which a state-owned corporation acting under commercial conditions would not necessarily be considered a public body.

A second key question is the permissibility and propriety of out-of-country benchmarks. Is the Chinese government sufficiently involved in the relevant industries to preclude the use of domestic commercial markets as a benchmark in order to determine the benefit of the subsidy provided to the recipient? If so, then how should out-of-country benchmarks be chosen and calculated? The AB, leaning heavily on findings in US–Softwood Lumber IV,Footnote 4 concluded that the fact that the Chinese government is the predominant supplier makes it likely that private prices will be distorted; nonetheless, the AB indicated that a case-by-case analysis is still required.

The AB clearly had difficulties with the cavalier Panel review of the USDOC's findings on appropriate out-of-country benchmarks. It considered that the Panel did not review the methodology employed by the USDOC in constructing an out-of-country benchmark for China's local-currency interest rates with the rigor required to satisfy the ‘objective assessment’ standard. While the AB made this ruling on the basis of Article 11 of the WTO Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU), which is normally characterized as a ‘procedural’ provision, the practical effect of the ruling should be to impose a level of discipline on the use of out-of-country benchmarks that investigating authorities might not have otherwise considered to exist.

2. Background to the dispute

In 2007, the US Department of Commerce (USDOC), in its dual anti-dumping and anti-subsidy investigation of Coated Free Sheet Paper (CFSP) from China, reversed its longstanding policy against applying the countervailing-duty law to countries it deemed to have ‘non-market economies’.Footnote 5 That policy, first adopted by the USDOC in 1984 and affirmed in 1986 by the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in the Georgetown Steel case,Footnote 6 was based on the view that, given the highly distortionary nature of the role played by the governments of centrally planned economies with no discernible private sector, it would not be appropriate to apply the countervailing-duty legislation to NMEs because a ‘non-market economy would in effect be subsidizing [itself]’.Footnote 7

In CFSP, the USDOC reconciled the Georgetown Steel case − which the Supreme Court did not hear and remains ‘good law’ in the United States as of the time of this writing − with its decision to apply countervailing duties against China by distinguishing the ‘Soviet-style economies of the 1980s’,Footnote 8 which were the subject of the Georgetown Steel case,Footnote 9 with present-day China. The USDOC considered that, while China should remain ‘an NME for purposes of the US anti-dumping law’Footnote 10 in light of the continued perceived distortion in China's domestic sales prices and costs and thus their inability to produce reliable ‘normal values’, China's economy had nevertheless changed in fundamental ways such that it was no longer considered to resemble the ‘traditional Soviet-style command economy’Footnote 11 that was the subject of the Georgetown Steel case.

Pricing committees, or similar state agencies, administratively set nearly all prices in the Soviet-style economies of the 1980s. Moreover, prices were not fixed with any deference to the forces of supply and demand, but rather served as an accounting device between supplier and consumer enterprises. In contrast, although price controls and guidance remain on certain ‘essential’ goods and services in China, the PRC Government has eliminated price controls on most products; ‘market forces now determine the prices of more than 90 percent of products traded in China’.Footnote 12 (Emphasis added)

Beyond the issue of whether, given its NME status in the AD context, the USDOC could apply its CVD legislation to China in any manner, the USDOC's change of course on China raised a key issue that would go on to be the focus of this WTO dispute.Footnote 13 This concerned what is commonly termed the ‘double-remedies’ issue, where double remedies are considered to occur in situations in which the concurrent imposition of CVDs and ADDs has the effect of offsetting twice the same instance(s) of subsidization. Although the CFSP investigation itself did not actually result in the concurrent imposition of CVDs and ADDs, the four subsequently initiated dual investigations against Chinese goods did, and thus they, together, served as the basis for China's requests for the establishment of a WTO Panel.Footnote 14

In CFSP as well as the four subsequent investigations, the Chinese producers had argued before the USDOC that because China was designated an NME in the parallel AD investigations and thus subject to the United States's surrogate-country ‘NME methodology’ for the calculation of normal values, any ADD calculated on the basis of that methodology would necessarily reflect any instances of subsidization, thereby rendering CVDs duplicative. The basis for this argument stems from the fact that, under US law, normal values based on surrogate countries are presumed to be unsubsidized, and thus not ‘depressed’ or affected in any way by subsidies granted by the government that is the target of the investigation. Where that is the case, the dumping margin on which the eventual duty is based would be higher than it would be if the normal value were depressed by the subsidies. This assumes, of course, that the subsidies countervailed in the parallel CVD investigation would have, in fact, depressed the normal value in the AD investigation pro rata (or ‘dollar for dollar’) if Chinese domestic costs/prices were actually used to derive the normal value used in the comparison between export price and normal value.

In response to the argument that double remedies were impermissible under US law and that it was incumbent upon the USDOC to adopt a methodology that would ensure that they not be imposed, the USDOC considered that absent an explicit statutory directive to address the issue, US CVD legislation does not permit any adjustment – the full value of the benefit must be offset by the CVD (regardless of how much of the benefit is passed through to prices). The USDOC also considered the assumption on which the argument was based, i.e. that non-export-contingent subsidiesFootnote 15 lower domestic prices pro rata, to be flawed in any event,Footnote 16 and went on to impose concurrent CVD and ADD in the four investigations underlying the WTO complaint, as well as several others initiated afterwards.

Apart from the double-remedies issue, the USDOC's decision to apply the US CVD legislation to China also raised a host of issues relating to how the substantive provisions of the CVD legislation − mostly relating to the identification and quantification of subsidies − could be applied to a country still considered, at least by the United States, to be in transition from its ‘command-economy past’.Footnote 17 Examples of this include the relevance of China's ‘Five Year Guidelines’ and other planning documents in the determination of de jure specificity of subsidies; the scope of the meaning of the term ‘public body’ as it relates to the question of whether China's state-owned commercial banks (SOCBs) and other state-owned enterprises (SOEs) can be considered to be providing goods and services as government actors; and the circumstances in which it is appropriate to consider SOEs’ involvement in an industry sufficient to render any domestic price in that industry incapable of providing an ‘undistorted’ benchmark for the purposes of calculating the amount of the benefit received, and then how to construct an out-of-country benchmark.

While most of the more contentious aspects of the underlying investigations and WTO dispute relate to topics that are common in many CVD investigations, such as the determination of specificity and the calculation of benefit amounts, the legally relevant facts of this dispute tend to relate more to issues that are germane to China's economy in particular and as a whole (as well as certain other NMEs perhaps), rather than the specific producers or even the specific industries targeted by the investigations. It is for that reason that this dispute, while only targeting the first four USDOC investigations resulting in concurrent ADDs and CVDs, should nevertheless have wide-reaching consequences for all of the investigations conducted against China up to the point of the issuance of the AB Report, as well as those to be initiated in the future.

3. Key issues examined in the Panel and AB reports

3.1 Double remedies

The Panel in this dispute ruled in favor of the United States on most issues of systemic importance. With regard to the double-remedies issue, the arguments put before the Panel by China were significantly different from the arguments treated by the USDOC at the investigation stage, and later the US Court of International Trade (CIT), because of the differences between the US CVD law and the text and substantive provisions of the GATT and the SCM Agreement. Though China cited no less than eight different articles of the GATT and the SCM AgreementFootnote 18 in support of its contention that the USDOC's imposition of double remedies in the underlying investigations was impermissible, the Panel rejected the arguments made in connection with each. Hence, even though the Panel found that double remedies were likely to occur, the articles cited by China simply did not address the issue of double remedies.Footnote 19

The AB disagreed and considered that, when read in light of various other articles for context, Article 19.3 of the SCM Agreement, which requires that duties be collected ‘in appropriate amounts’,Footnote 20 forbids the imposition of concurrent duties which offset the same subsidization twice. In addition to finding the concept of the collection of duties constituting double remedies to be incompatible with the notion of ‘appropriateness’,Footnote 21 the AB went a step further and placed the burden of proof on the investigating authority to rebut the presumption that there is, in fact, double counting in cases in which a parallel AD/CVD investigation makes use of an AD NME methodology. The AB considered that while it did not necessarily agree with the pro rata argument advanced by China, and the accompanying conclusion that CVDs in dual investigations using NME methodologies were entirely accounted for in the dumping investigations, double remedies were nevertheless ‘likely’ to occur in such dual investigations.Footnote 22 This likelihood seemed to be the impetus for the AB's shifting of the burden onto the investigating authorities.

3.2 The ‘public body’ determination

With regard to the issues concerning the identification of subsidies pursuant to Articles 1 and 2 of the SCM Agreement, the Panel first treated the issue of whether the USDOC acted in a manner inconsistent with Article 1.1(a)(1) of the SCM Agreement in considering that China's SOCBs and SOEs were ‘public bodies’. Considering the term ‘public body’ to encompass ‘any entity controlled by a government’,Footnote 23 where ‘majority government ownership is clear and highly indicative evidence of government control’,Footnote 24 the Panel went on to find with relative ease, in light of the fact that the SOEs were majority owned by the Chinese government, that the USDOC did not act inconsistently with Article 1.1(a)(1) by ‘giving primacy to evidence of majority government-ownership’. The Panel reached a similar conclusion in the context of the SOCBs in light of the majority government ownership of the banks, and considered it relevant that the USDOC concluded that, in addition to simple ownership, ‘there was extensive government involvement in and control over [the SOCBs’] operations’.Footnote 25

The AB overruled the Panel on this issue as well, finding its interpretation of the term ‘public body’ too broad. As opposed to the Panel's focus on ‘control’, the AB considered that:

the determination of whether a particular conduct is that of a public body must be made by evaluating the core features of the entity and its relationship to government in the narrow sense. That assessment must focus on evidence relevant to the question of whether the entity is vested with or exercises governmental authority.Footnote 26

It was on this basis that the AB overruled the Panel's acceptance of the USDOC's decision considering certain of China's SOE input suppliers to be public bodies. Instead of performing an analysis on the basis of the sort of factors listed by the AB, the USDOC ‘appl[ied] a rule of majority government-ownership’,Footnote 27 which the AB found unacceptable. The AB did, however, consider the approach of the USDOC with regard to the SOCBs to be acceptable under its new formulation. In the case of the banks, the USDOC did not apply the ‘simple ownership’ test, but rather took into account various other considerations which the AB considered to, as a factual matter, not be incompatible with the conclusion that the entities in question exercised governmental authority.

3.3 De jure specificity in lending and regional specificity in land-use rights

China's claims concerning specificity determinations pursuant to Article 2 of the SCM Agreement consisted of one attacking the determination of de jure specificity in the context of SOCB lending to the tire industry under Article 2.1(a) of the SCM Agreement, and another attacking the determination of regional specificity in the context of the provision of land-use rights under Article 2.2.

With regard to the first, the Panel reviewed the evidence considered by the USDOC in making its specificity determination in the Certain New Pneumatic Off-the-Road Tires investigation, including but not limited to: ‘central government planning documents’ which singled out the tire industry as ‘encouraged’; ‘provincial and municipal government planning documents’ considered to implement the centrally mandated plan; provisions of those documents relating to the financing of that industry, and China's Commercial Banking Law, which was considered to require the SOCBs to consider government macroeconomic policies in making lending decisions.Footnote 28 The Panel then concluded, on the basis of the totality of the evidence and affording the USDOC due deference as a trier of fact, that ‘a reasonable and objective investigating authority could have determined … [that China] explicitly identified “certain enterprises” in the sense of Article 2.1(a) of the SCM Agreement for encouragement and development’.Footnote 29

On appeal, the AB understood China to be focusing its challenge more on the relationship between the Panel's analysis and the USDOC's analysis than the specificity conclusion itself. On that point, the AB did acknowledge a disconnect between ‘certain elements of the Panel's reasoning [and] the rationale employed by the USDOC in its specificity determination’ but did not consider that to amount to legal error given the facts of the case.Footnote 30 The AB therefore upheld the Panel on this issue.

China's other specificity-related claim, that the USDOC acted inconsistently with Article 2.2 of the SCM Agreement in considering the land-use rights granted to one of the companies in the Laminated Woven Sacks (LWS) investigation to be ‘regionally specific’, marked what was probably the most substantial of China's few wins at the Panel stage. In a decision that was not appealed by the United States, the Panel considered that even though the industrial park in which the allegedly subsidized land was located could constitute a ‘geographical region’ within the meaning of Article 2.2,Footnote 31 the USDOC nevertheless erred in considering that location within the park could, in itself, constitute the grant of a regionally specific subsidy. The Panel noted that such an analysis, combined with the USDOC's finding that the government was the ultimate owner of all land in China, led to the problem of ‘land-use rights, wherever in China they were provided, [being] regionally specific’ on account of their necessarily being located somewhere.

Thus, the Panel considered that a proper finding of regional specificity in such circumstances would require the land to have been provided pursuant to some sort of distinct regime, such that evidence would point to a fundamental difference between the provision of land-use rights within the geographical region and that located outside of it.Footnote 32 While the United States did not appeal this decision, China did, citing the systemic implications that the Panel's reasoning could have, but the AB did not consider the Panel to have erred.Footnote 33

3.4 Out-of-country benchmarking

3.4.1 The permissibility of out-of-country benchmarking

With regard to the provision of (1) land-use rights, (2) financing through preferential lending, and (3) steel inputs sold by entities considered to be public bodies, the USDOC had considered that the Chinese Government's involvement in the relevant markets was so pervasive that there was effectively no domestic ‘commercial’ (i.e., undistorted by government intervention) market that could serve as a benchmark against which to compare the price of the good or service provided in order to determine the benefit of the subsidy provided to the recipient. Accordingly, the USDOC resorted to the construction of ‘out-of-country benchmarks’ in order to calculate the amount of benefit of the subsidies to their recipients.

With respect to all three broad benefit categories, the Panel held that the USDOC was justified under Article 14 of the SCM Agreement in its determinations that the relevant industries were distorted to the point that they precluded the selection of a domestic benchmark. In each case, the Panel afforded the USDOC relatively wide discretion with regard to its factual conclusions, focusing primarily on the quality of the evidence examined in each case. With regard to SOE-produced steel inputs, the Panel upheld the USDOC's determination that the Chinese steel industry was incapable of producing a reliable domestic benchmark principally, but not solely, on account of the SOEs’ market share and very dominant position in the market (96.1%). With regard to the land-use rights, the Panel upheld the USDOC's determination that because of the prohibition of private land ownership in China such that ‘all land [is] owned by some level of government’, there is essentially no commercial market for land in China.Footnote 34 The Panel analyzed both the steel input and land-use right questions under Article 14(d) of the SCM Agreement, and relied heavily on the AB Report in US–Softwood Lumber IV, which first established the possibility of resorting to an out-of-country benchmark.

The Panel's analysis of China's claim relating to the decision to use out-of-country interest-rate benchmarks for the purposes of determining the benefits provided by China's ‘policy-lending program’ was similar to that in the land and steel contexts, except in that loans are treated under Article 14(b) of the SCM Agreement, and likewise the Panel seemed to rely heavily on the deferential ‘adequate and reasoned conclusion’ standard. In concluding that ‘a reasonable and objective investigating authority could have concluded that the government played a predominant role in the Chinese commercial lending market … such that the observed rates were not suitable as benchmarks’,Footnote 35 the Panel did not give much of an indication on what it thought about the USDOC's conclusions on the substance, but clearly found particularly persuasive the ‘extensive reference to publications by outside institutions (OECD and IMF)’Footnote 36 as well as the thoroughness of the USDOC's investigation on this question.

The AB upheld the Panel's conclusions with regard to the two benefit categories challenged in this regard (China did not challenge the land-use rights’ determination), clarifying and expanding its interpretation of the US–Softwood Lumber IV Report which formed the basis for the Panel's holdings. With regard to the steel inputs and the importance of the government being the ‘predominant supplier’ in the industry, the AB noted that it considered US–Softwood Lumber IV to indicate that ‘if the government is a significant supplier, this fact alone cannot justify a finding that prices are distorted’.Footnote 37 However, ‘where the government is the predominant supplier, it is likely that private prices will be distorted, but a case-by-case analysis is still required’.Footnote 38 Because of the overwhelming predominance of the Chinese SOEs in the steel market (relevant to the two pipe and tube cases), along with what the Panel considered to be the USDOC's consideration of ‘other factors’ thus eschewing the application of the forbidden ‘per se rule’ with respect to market share, the AB upheld the Panel's decision.

The AB similarly upheld the USDOC's rejection of in-country interest rates for RMB-denominated loans, first noting that ‘inherent in Article 14(b), as in Article 14(d), is sufficient flexibility to permit the use of a proxy in place of observed rates in the country in question where no “commercial” benchmark can be found’.Footnote 39 Having officially expanded the US–Softwood Lumber IV reasoning with regard to Article 14(d) of the SCM Agreement (goods and services) to Article 14(b) (loans), the AB went on to consider that the USDOC's analysis was in fact sufficient to conclude that ‘the Chinese Government, by participating in the RMB-lending market and by intervening in that market (beyond its monetary policy role), is able to and does in fact distort interest rates’.Footnote 40 The analysis to be made in the lending context is thus markedly different from the analysis in the goods-and-services context in that the government being a substantial or predominant supplier of loans is not necessarily a relevant inquiry, especially when the government interference is such that even foreign banks are affected in their lending practices such that their rates must be deemed ‘non-commercial’.

3.4.2 The propriety of the actual benchmarks selected

Pursuant to its determination that the Chinese land and lending industries, the latter with regard to both Chinese RMB- and USD-denominated loans, were distorted such that they required out-of-country benchmarks for the purpose of the benefit quantification, the USDOC went on to select as proxies Thai land prices, an interest rate based on a ‘regression analysis of inflation-adjusted interest rates in 33 lower-middle-income countries’,Footnote 41 and ‘an annual average LIBOR-based interest rate’, respectively.Footnote 42

In its evaluation of the consistency of the benchmarks with Article 14 of the SCM Agreement, the Panel determined that, just as a finding of a certain level of distortion is the fact that permits an authority to resort to an out-of-country benchmark in the first place, the benchmark construction process requires an ‘investigating authority to do its best to identify a benchmark that approximates the market conditions that would prevail in the absence of the distortion’.Footnote 43 The Panel also considered that its task in this regard was essentially limited to the evaluation of ‘the internal logic of the methodology employed, and the soundness and appropriateness of the data relied upon’Footnote 44 for the construction of the proxy benchmark. As was the case with the review of the USDOC's initial distortional analyses, the Panel considered itself similarly constrained by its standard of review, which dictates that it only seek to determine whether the selected benchmarks are such that ‘a reasonable and objective investigating authority could use’Footnote 45 them.

In a holding not appealed by China, the Panel considered itself satisfied that the method adopted in order to determine the land benchmark was consistent with Article 14(d), primarily because of the range and variety of factors that the USDOC took into account in determining the likeness between the Thai and Chinese land markets. In a holding not appealed by the United States, the Panel rejected the LIBOR-based benchmark used for benchmarking USD-denominated loans, though only on the basis of the fact that the USDOC used yearly average rates to construct the benchmark, as opposed to the actual LIBOR rates prevailing at the time that the loans countervailed were granted.Footnote 46 This detail, therefore, would not hinder in any meaningful way the United States's ability to countervail USD-denominated loans using a LIBOR-based benchmark, but it would require the USDOC to employ slightly more labor in matching each loan with the prevailing benchmark at the time of the loan, as opposed to using the rejected ‘one size fits all’ approach.

Finally, in a holding that was appealed by China, the Panel held with regard to the United States's benchmark for RMB-denominated loans that the benchmark selected passed muster under the standard of review discussed above. Similar to its analysis in the land context, the Panel looked at the methodology employed by the USDOC, as opposed to the result of the application of the benchmark, and considered the various aspects of the methodology to be ‘appropriate’ and ‘not unreasonable’. These included the decision to rely on a basket of other countries’ currencies as the basis for the proxy, the selection of that basket according to a preexisting World Bank grouping of countries in the same income category as China, an inflation adjustment, and various other factors ‘related to the quality of the countries’ institutions’,Footnote 47 such as ‘political stability, government effectiveness and rule of law.’Footnote 48 The Panel concluded by noting that it did not consider the benchmark to be ‘perfect’, but only that a ‘reasonable and objective investigating authority could have used the methodology used by the USDOC’, and that it did not appear arbitrary or biased.Footnote 49

In a holding of uncertain practical effect in light of its procedural nature, the AB nullified the Panel's holding on the benchmark used for RMB-denominated loans not on substantive grounds, but rather because the AB considered the Panel's analysis so cursory as to violate its obligation under Article 11 of the DSU to perform an ‘objective assessment of the matter’.Footnote 50 The AB considered, in a passage characteristic of its general view on the Panel's analysis, that the Panel ‘appear[ed] to have simply accepted the USDOC's determinations and relevant supporting evidence without engaging in a critical and searching analysis, or testing the adequacy and reasonableness of the USDOC's determinations in the light of other plausible alternative explanations’,Footnote 51 and that it ‘rather passively accepted the reasons provided by the USDOC for its determinations, without engaging in a critical and searching analysis and without considering the USDOC's determinations in the light of plausible alternative explanations’.Footnote 52

While the AB did not go on to complete the analysis because of what it considered to be insufficient undisputed facts on the record that would permit such completion, the AB did go beyond merely criticizing the cursory nature of the Panel's analysis. Indeed, it effectively overruled the Panel's interpretation of its standard of review in the context of the evaluation of the consistency of out-of-country benchmarks with Article 14 of the SCM Agreement. The clearest example of this comes in the form of the AB's holding the Panel's description of its own mandate − as being limited to the examination of the ‘internal logic of the methodology’ and ‘soundness of the data’ used − to be in itself incapable of discharge of the ‘objective assessment’ obligation.Footnote 53

In addition, the AB's explanation that the Panel had an obligation to review ‘whether the reasons put forth by the USDOC justified the proxy that it constructed, including in the light of other plausible alternatives’,Footnote 54 indicates that it views the level of deference to be afforded to investigating authorities to be one which requires that the benchmark selected was, given the circumstances of the investigation, reasonable, and not merely that it could have been reasonable. To the extent that the AB suggests that the benchmark selected must be reasonable in comparison to other potential candidates, and not simply unreasonable on its face, as the Panel's analysis suggested, this would seem to imply the imposition of a substantive obligation on authorities to adequately examine the various potential benchmarks.

4. Legal and economic analysis

US–AD and CVD (China) presents four issues of systemic interestFootnote 55 pertaining basically to the conduct of AD and CVD investigations against perceived nonmarket economiesFootnote 56 such as China. These are:

(1) double remedies;

(2) qualification as ‘public bodies’ within the meaning of Article 1.1(a)(1) of the SCM Agreement of SOCBs and SOEs;

(3) de jure specificity of loans granted by SOCBs and regional specificity of land-use rights; and

(4) the decision to use and selection of out-of-country benchmarks within the meaning of Article 14(b) and 14(d) of the SCM Agreement.

Before delving into the analysis of these issues, it seems useful to provide a brief recap of the notion of nonmarket economies and its consequences in the trade remedies’ context in the GATT/WTO.

4.1 Nonmarket economies in the GATT/WTO

The second interpretative note Ad Article VI(1) GATT 1947 (hereinafter: second Ad note) provides that:

It is recognized that, in the case of imports from a country which has a complete or substantially complete monopoly of its trade and where all domestic prices are fixed by the State, special difficulties may exist in determining price comparability for the purposes of paragraph 1, and in such cases importing contracting parties may find it necessary to take into account the possibility that a strict comparison with domestic prices in such a country may not always be appropriate.

Thus, this note gives GATT members carte blanche to determine normal value in AD investigations involving countries meeting these criteria.Footnote 57 In practice, members developed the surrogate- or analogue-country concept for this purpose, meaning that they would use prices or costs in a market-economy country as the basis for normal value.Footnote 58

Furthermore, as neither this note nor any other provision in the GATT (or the WTO) provides a listing of countries that have a ‘complete or substantially complete monopoly of their trade and where all domestic prices are fixed by the State’ (colloquially and in various instances of WTO members’ domestic-trade-remedies legislation referred to as nonmarket economies), it was left to GATT members to unilaterally determine which countries met these requirements. While a GATT member holding that another GATT member met the requirements might have quickly found itself the subject of a dispute-settlement proceeding that it probably would have lost – after all, it is hard to find a country that has a complete or substantially complete monopoly of its trade and where all domestic prices are fixed by the State – non-GATT members of course did not have this possibility, as a result of which countries such as China, Russia, Ukraine, and Vietnam were routinely treated as nonmarket economies and subjected to the surrogate-country methodology, which in light of, among others, the incomparable nature of the surrogates chosen and their lack of incentive to cooperate (except to obtain a competitive advantage over their ‘non-market economy’ competitors) almost invariably led to findings of high dumping margins.

While Russia and Ukraine, over time, managed to be treated as market economies by countries such as the United States and the EU, ostensibly because they met the technical criteria unilaterally established by the latter, but in reality arguably because of political considerations, China (and Vietnam) had to agree to special provisions in their Protocols of Accession to the WTO effectively allowing other WTO members to continue to treat them as nonmarket economies until 2016 and 2019, respectively, whether or not the conditions of the second Ad note are actually met. Indeed, in the case of China, a recognition among the negotiating members that its economy as of 2001 could not reasonably be characterized as the sort referred to in the Ad note is what prompted the inclusion of the special provision in the first place.

Thus, paragraph 15 of China's Accession Protocol states that:

15. Price Comparability in Determining Subsidies and Dumping

Article VI of the GATT 1994, the … Anti-Dumping Agreement and the SCM Agreement shall apply in proceedings involving imports of Chinese origin into a WTO Member consistent with the following:

(a) In determining price comparability under Article VI of the GATT 1994 and the Anti-Dumping Agreement, the importing WTO Member shall use either Chinese prices or costs for the industry under investigation or a methodology that is not based on a strict comparison with domestic prices or costs in China based on the following rules:

(i) If the producers under investigation can clearly show that market economy conditions prevail in the industry producing the like product with regard to the manufacture, production and sale of that product, the importing WTO Member shall use Chinese prices or costs for the industry under investigation in determining price comparability;

(ii) The importing WTO Member may use a methodology that is not based on a strict comparison with domestic prices or costs in China if the producers under investigation cannot clearly show that market economy conditions prevail in the industry producing the like product with regard to manufacture, production and sale of that product.

(b) In proceedings under Parts II, III and V of the SCM Agreement, when addressing subsidies described in Articles 14(a), 14(b), 14(c) and 14(d), relevant provisions of the SCM Agreement shall apply; however, if there are special difficulties in that application, the importing WTO Member may then use methodologies for identifying and measuring the subsidy benefit which take into account the possibility that prevailing terms and conditions in China may not always be available as appropriate benchmarks. In applying such methodologies, where practicable, the importing WTO Member should adjust such prevailing terms and conditions before considering the use of terms and conditions prevailing outside China.

…

(d) Once China has established, under the national law of the importing WTO Member, that it is a market economy, the provisions of subparagraph (a) shall be terminated provided that the importing Member's national law contains market economy criteria as of the date of accession. In any event, the provisions of subparagraph (a)(ii) shall expire 15 years after the date of accession. In addition, should China establish, pursuant to the national law of the importing WTO Member, that market economy conditions prevail in a particular industry or sector, the non-market economy provisions of subparagraph (a) shall no longer apply to that industry or sector.

Until 11 December 2016 therefore, WTO members may use the surrogate-country methodology for China on the basis of paragraph 15(a)(ii) of the Protocol. On that date, paragraph 15(a)(ii) will expire and the special rules for normal-value determination applicable to China can no longer be applied as explicitly clarified by the AB in EC–Fasteners:

Paragraph 15(d) of China's Accession Protocol establishes that the provisions of paragraph 15(a) expire 15 years after the date of China's accession (that is, 11 December 2016). It also provides that other WTO Members shall grant before that date the early termination of paragraph 15(a) with respect to China's entire economy or specific sectors or industries if China demonstrates under the law of the importing WTO Member ‘that it is a market economy’ or that ‘market economy conditions prevail in a particular industry or sector’. Since paragraph 15(d) provides for rules on the termination of paragraph 15(a), its scope of application cannot be wider than that of paragraph 15(a). Both paragraphs concern exclusively the determination of normal value. In other words, paragraph 15(a) contains special rules for the determination of normal value in anti-dumping investigations involving China. Paragraph 15(d) in turn establishes that these special rules will expire in 2016 and sets out certain conditions that may lead to the early termination of these special rules before 2016.Footnote 59

Therefore, from 11 December 2016, Section 15 of the Accession Protocol can no longer be relied upon to use the surrogate-country methodology as regards Chinese imports in AD investigations.

This still leaves open the question whether post-2016 WTO members could possibly rely on the second Ad note to effectively continue use of the surrogate-country methodology. However, per the AB in EC–Fasteners this appears unlikely:

The second Ad Note to Article VI:1 refers to a ‘country which has a complete or substantially complete monopoly of its trade’ and ‘where all domestic prices are fixed by the State’. This appears to describe a certain type of NME, where the State monopolizes trade and sets all domestic prices. The second Ad Note to Article VI:1 would thus not on its face be applicable to lesser forms of NMEs that do not fulfill both conditions, that is, the complete or substantially complete monopoly of trade and the fixing of all prices by the State.Footnote 60

Last, it is noted at this stage that the various Protocols of AccessionFootnote 61 do foresee the imposition of countervailing duties against NMEs, though – supposedly in light of the then-prevailing practice among the principal trade defence users of not applying their CVD laws to NMEs – there was no provision explicitly accounting for the possibility of double remedies in concurrent AD/CVD investigations against NMEs. In this respect, one may draw a parallel with model zeroing, which did not exist as a practice as long as WTO members were free to apply simple zeroing.

4.2 Double remedies

4.2.1 Pass-through

The fact that simultaneous imposition of ADD and CVD may lead to double remedies has been recognized by the GATT signatories from the outset. Article VI:5 GATT provides that ‘no product … shall be subject to both anti-dumping and countervailing duties to compensate for the same situation of dumping or export subsidization’. The fact that Article VI:5 GATT notes the impermissibility of double remedies in the context of export subsidies but not domestic subsidies was a key element of the United States's legal argument.

The following two examples clarify why the GATT distinguishes between export and domestic subsidies. First, consider an example where a producer receives an export subsidy of US$5/unit; she sells in her domestic market at US$100 and for export at US$95; the effect of the export subsidy is to lower the export price by US$5. Article VI:5 implies that the investigating authorities could either impose an ADD of US$5 or a CVD of US$5; however, it could not impose both because that would amount to double remedies.

One can criticize Article VI:5 on the grounds that it abstracts from what the recipient of the subsidy actually does with the money and/or, more generally, that it ignores the fungibility of money. More formally, Article VI:5 embodies two very specific assumptions about the pass-through of the export subsidy: (i) the export subsidy is completely passed through to the export price and (ii) none of the export subsidy is passed through to the home-market price. Despite the questionable empirical validity of the pass-through assumptions, the explicit link between the act of exporting and the receipt of an export subsidy appears to be the basis for limiting the scope of Article VI:5 to export subsidies.

Now contrast this example with the following, which involves a countervailable domestic subsidy of US$7. Suppose investigating authorities observe a domestic market price of US$93 and an export price of US$89. In addition, suppose investigating authorities (could) determine that without the domestic subsidy the domestic market price would have been US$100 and the export price would have been US$96. Under these circumstances, the proper trade remedy would involve both an ADD of US$4, which would eliminate the price differential, and a CVD of US$7, which would restore the prices to what they would be without the domestic subsidies. Like the previous example, this example embodies very specific (and again perhaps empirically invalid) assumptions about pass-through of the subsidy; notably, the domestic subsidy is assumed to symmetrically and completely pass through to both the export price and the home-market price.Footnote 62

These examples make it clear that the economic logic behind Article VI:5 GATT hinges on the pass-through effects of domestic and export subsidies being different. One type of subsidy (export subsidy) is presumed to affect the export price (after all, it is contingent on export) and have little impact on the normal value, while the other type of subsidy (domestic subsidy) is believed to affect the export price and normal value comparably.

In practice, however, the economic effects of export and domestic subsidies are likely to be far murkier. Export subsidies may well affect home-market prices. Similarly, it is not hard to imagine a situation where, for example, a domestic subsidy has a large effect on the home-market price but a small impact on the export price. An enormous economics literature has examined pass-through both theoretically and empirically over the past two decades, and there is overwhelming evidence that pass-through is neither complete nor symmetric.Footnote 63 Even weak forms of the ‘law of one price’, which follows from an assumption of symmetric pass-through, are rejected in empirical study after empirical study.Footnote 64 Economists have repeatedly found that pass-through will not typically be symmetric across destination markets. The robust empirical finding is that a cost shock will result in a price change of x% to one market but of y% to another market. Market structure, technology, upstream and downstream cost conditions, market share, the nature and duration of cost shocks, and product differentiation have all been found to affect pass-through.

This discussion is at the heart of our assessment of the AB's decision. On the one hand, we believe the AB failed to appreciate that specific provisions in US statutes imply that the calculated pass-through will be essentially the same as the pass-through assumed in Article VI:5 GATT. Specifically, the United States's methods result in a domestic subsidy having price pass-through effects similar to that which Article VI:5 GATT implicitly assumes occurs with an export subsidy. US AD NME methods entirely eliminate the impact of domestic distortions (including any subsidization) on the normal value side; hence subsidies can only pass through to the export price. Therefore, double remedies will definitely occur under US procedures.Footnote 65

If the AB had recognized and embraced this economic logic, it could have narrowly crafted its report by using the underlying logic of Article VI:5 GATT in support of a finding that the simultaneous use of AD and CVD under US methods is always inconsistent under the NME method. This strong but narrow approach would have allowed the AB to make a definitive statement about double remedies but to limit the scope of the determination to just the US NME methodology.

On the other hand, the AB may have made a deliberate decision to craft a broader decision. The AB seemed to recognize that, in general, double remedies and pass-through are fundamentally empirical questions. The empirical literature has shown that pass-through is rarely 100% and rarely 0%. How much of a domestic subsidy passes through to the home-market price and how much passes through to the export price is something an investigating authority should measure and then make adjustments for. We believe this latter interpretation is the most logical way to interpret the AB's decision and explanation.

Even though the AB supposedly opted for a broader interpretation, it was incumbent upon the AB to have considered how domestic subsidies pass through to normal value under NME methods as compared with other methods for computing normal value. Had it done so, it would have been able to comment on the specifics of US procedures that generate double remedies.

4.2.2 Methods for calculating normal value

The pass-through issue is complicated by the fact that the ADA provides for four alternative methods for calculating the normal value in a dumping determination: the home-market method, the constructed-value method, the third-market method, and the NME method. Pass-through of a domestic subsidy may vary depending on the method used. Moreover, at the time when a firm sets its prices, it does not know what method would be used if it were to later find itself subject to an anti-dumping investigation. This uncertainty further dims the prospect of empirically observing symmetric pass-through.

In broad terms, the dumping margin is calculated as

where home-market costs are denoted as C Home and the subsidy is denoted s. The computation of P normal_value varies by the specific method used. That is

The domestic subsidy may take the form of direct cash support by the government or subsidized-loan terms. The subsidy can also affect the costs of production, say by offering the firm(s) lower electricity rates, lower input costs, etc. This latter type of subsidy is referred to as the provision of goods or services at less than adequate remuneration (LTAR) and was an important form of subsidization in several of the investigations that were the basis for this dispute.

Under the home-market method for determining normal value, an investigating authority would compare the home-market price (P Home) with the export price (PexpUS). The examples in the preceding subsection were based on this method. Economic theory implies that both prices depend on the costs and therefore both prices should experience some pass-through of the subsidy.

Under the United States's constructed-value approach, the normal-value home-market price (P HomeCV) is calculated using a cost-plus approach. The USDOC first determines how much of each factor of production is needed to produce the good and then values each input using information on prices in the home market. For example, if a case involved a product from Japan, the United States would use Japanese home-market prices for labor, the raw materials needed to produce the product, electricity, etc., of the producer concerned when constructing the cost of the product. In addition, the USDOC will add a markup for selling, general, and administrative expenses and profits. However, the constructed-value method will not necessarily fully purge the subsidy distortion from either the normal value or the export prices, because home-market costs can be affected by the domestic subsidy, which in turn can affect both prices. Moreover, we expect asymmetric pass-through with the constructed-value approach. The reasoning is that the pass-through of the subsidy to the normal value is via a fixed-coefficient function that imposes a specific relationship between the subsidized inputs and the price. The pass-through to the normal value will not depend on other factors that economic theory tells us affects pass-through (e.g., the elasticity of demand). By contrast, pass-through of the subsidy to the export price will depend on pass-through elasticity, which depends on many factors such as market structure, the firm's share in the export market, technology, etc. We would not expect two such very different approaches to produce the same pass-through elasticity.

Under the third-country method, the export price of the like product to an appropriate third country is used for the normal value. As with the home-market method, standard microeconomic theory predicts that both prices – the export price to the third country (Pexp 3rd_mkt) and to the complaining market (P expUS) – will be affected by pass-through of the domestic subsidy via distorted input costs and/or direct subsidization.

The nonmarket-economy method is the final approach. The ADA gives importing countries significant discretion in the calculation of normal value of products exported from NMEs. As with the constructed-value method, the USDOC gathers information on the company's ‘factors of production’ – the physical quantities of all the inputs used in producing the merchandise. However, in the NME method, the USDOC values those inputs on the basis of prices in a surrogate country. The normal value (P HomeCV, surrogate) is therefore a cost-based normal value derived from company-specific factors of production combined with surrogate-country prices of those factors. At least in the United States, surrogate countries are market economies judged to be at a level of economic development similar to that of the NME country in question.Footnote 66 The USDOC only chooses surrogate costs that are deemed to be fairly traded. Thus, under the United States's NME procedures, a nonmarket economy's domestic subsidization program should have no effect on the constructed normal value. However, we acknowledge that subtle nuances in the precise constructed costs and specific input-pricing data might mean the NME constructed value is not fully neutered of the domestic subsidies. Even so, there can be no doubt that the US approach results in a considerably muted (if any) impact of the subsidies on the normal value. By contrast, NME's domestic-subsidization programs will have a more direct effect on the export price (P expUS) via distorted input costs and direct subsidization.

4.2.3 Pass-through and normal value

The double-remedies problem hinges on whether the impact of a domestic subsidy (which is being offset by a CVD) is also partially or fully captured by the ADD. For the home-market and third-country methods, if the subsidized firm passes through the subsidy symmetrically to all measured prices, then double counting will not occur, and the imposition of concurrent AD and CVD duties will not offset the subsidization twice. For these methods, double remedies do not depend on full pass-through but symmetric pass-through.

This, however, is not the case for AD margins using the NME method. The USDOC's NME approach means the main avenue, and in all likelihood the only avenue,Footnote 67 for the subsidy to influence the dumping margin is the export price. Therefore, double remedies are inevitable to some extent unless a given export subsidy has had zero impact on the export price – any difference between the NME normal value and the export price is already corrected by the ADD, at least to the extent that there has been pass-through to the export price. The objective of the United States's surrogate-country methodology is to calculate the price of the product, as if it would have been produced and/or sold unsubsidized by a producer in a market economy, i.e. under normal market conditions without government interference, the resulting normal value would normally be an unsubsidized price. The process of constructing the normal value for an NME should therefore purge all subsidies. Given that the subsidy has already been taken into account when calculating the dumping margin, a concurrent CVD will generate double remedies. USDOC NME procedures therefore virtually guarantee that double remedies will occur.

Article VI:5 GATT disallows simultaneous use of AD and CVD for export subsidies based on a presumption that the export subsidy will only affect the export price – when in fact within the firm money is fungible and hence it is possible an export subsidy could affect the home-market price too. We believe the economic basis for Article VI:5 GATT applies equally to the US NME methodology because domestic subsidies are essentially purged from the first term of the AD duty, P HomeCV(C surrogate), and are allowed to fully pass through to the second term, P expUS (CHome (s), s)

The implicit assumption of Article VI:5 GATT is the attenuated ability of an export subsidy to pass through to the normal value. Likewise, by selecting a ‘market economy’ surrogate country, the logic of the US NME methodology is designed to result in little or no ability for domestic subsidies in the NME to pass through to the normal value. Moreover, the United States's countervailing-duty statute required the CVD duty to be equal to the full value of the calculated benefit (i.e. prohibited any adjustment in light of pass-through or other considerations).Footnote 68

Therefore, the economic logic behind Article VI:5 GATT and the economic implications of US NME methods are the same. Given the particulars of US procedure, we believe Article VI:5 GATT could have been the basis for a strong definitive finding that the US practice was inconsistent. The AB instead opted for a more cautious approach. The AB concluded that ‘double remedies were “likely” to occur in cases where NME methodology is used to calculate the margin of dumping’ and permitted the United States to pursue implementation by focusing on how much double counting occurs.Footnote 69 The AB seemed to understand that if an investigating authority were to make adjustments to account for such double counting, then the two remedies could be used simultaneously. Depending on the specific procedures, such adjustments may resolve the double-remedies issue.

Nevertheless, by focusing on measurement the AB may have inadvertently opened the door to additional double-remedy challenges. What if affected countries can measure and document the extent of double remedies under other methods for calculating normal value? It seems improbable that the WTO would allow double remedies under some methods for calculating normal value but not under the NME method.

4.2.4 Examples of double remedy

The AB's Report does not clearly address (i) the pass-through implications of Article VI:5 GATT and (ii) the applicability of that logic for the current dispute, especially given the specifics of US AD and CVD rules. The AB's determination has resulted in the dispute being viewed as a measurement issue. Even the United States acknowledges that measurement is extremely messy and complicated.Footnote 70 Going forward, it will be very difficult for future Panels to ascertain whether the measurement was in fact done correctly.

We now present two examples of the implementation approach proposed by the AB. In the first example, the subsidies are of the form of lower (LTAR) input costs. In the second example, we consider the situation where market-benchmark prices (used in the CVD calculations) differ from the surrogate-country prices (used in the AD calculations).

Example 1 – subsidized inputs

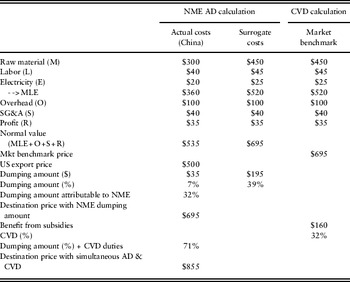

We begin with a simple example where the subsidies only affect the ‘materials, labor, and electricity’ costs of the firm (see Table 1).

Table 1. Double remedy–subsidized inputs

AD duty calculation

To keep the example as simple as possible, we assume other factors in the USDOC's factors-of-production analysis (overhead, SG&A, and profit) are not affected by the subsidies. In this example, we assume that (i) the material inputs are subsidized by US$150 less than their surrogate cost (US$300 versus US$450), (ii) labor costs are subsidized by US$5 (US$40 versus US$45), and (iii) electricity costs are subsidized by US$5 (US$20 versus US$25). As a result, the cost of the firms’ ‘material, labor, and electricity’ (or MLE) is US$160 less than their comparable surrogate values (US$360 versus US$520).

We assume the Chinese firm's home-market price is US$535 and the export price is US$500.Footnote 71 If China were considered a market economy and the home-market method were used to compute normal value, then the dumping amount would be US$35 (US$535 less US$500), implying an AD margin of 7%.Footnote 72

Under US NME rules, however, the home-market prices for materials, labor, and electricity would be replaced by those in the surrogate country. For instance, the USDOC might use Thai costs. In our example, we have an NME normal value of US$695, which implies a dumping amount of US$195 (or 39%). Of the dumping amount obtained using NME methods, 32% is due to using the NME methodology (39% less 7%).

CVD duty calculation

Under US CVD rules, the subsidy benefit is based on a USDOC ‘market benchmark’ valuation. As we have discussed at length elsewhere in this paper, the choice of the market benchmark is a matter of considerable importance in CVD cases. The USDOC attempts to ascertain what the market prices were at the time the Chinese firms purchased the inputs. Given that it was investigating both AD and CVD allegations, it would seem sensible (and simplest) if the USDOC just used the prices in the surrogate country (which were determined during the AD part of the investigation). However, that is not what the USDOC does. Instead, it creates what it believes is a representative market price. This market-benchmark price could be the average of prices in ‘comparable’ countries, be based on another country's price, or be based on reliable and verifiable market information. In some cases, the market-benchmark price is the same as the surrogate-country price. Often it is not.

To keep this first example as simple as possible, we assume that the market benchmark is the same as the surrogate cost. This means that the USDOC would determine that the subsidy benefit is US$160 (US$695 less US$535), implying a CVD of 32%. This is precisely the dumping amount that is due to NME methods. In other words, in this example the CVD is exactly equal to the dumping amount attributable to NME methodology. The full amount of the CVD is a double remedy.

If there is any doubt that double remedies have a large effect, the normal-value calculation is US$695. This, in fact, would be the destination price with the NME AD duty levied. However, if the unadjusted CVD is also levied, the destination price is US$855.

Example 2 – Subsidized inputs combined with mismatch of market benchmarks and surrogate-country valuations

We again assume that the subsidy only affects material, labor, and electricity costs (see Table 2). The additional complication in this example is due to the difference between the market-benchmark and surrogate-country valuations.

Table 2. Double remedy–subsidized inputs and market-benchmark complications

AD duty calculation

The AD duty calculation, in this second example, is the same as in the previous example. Due to the subsidy, the firms’ MLE is US$160 less than the surrogate values (US$360 versus US$520).

We again assume the Chinese firm's home-market price is US$535 and the export price is US$500. If China were considered a market economy and the home-market method were used to compute normal value, then the dumping amount would be US$35 (US$535 less US$500), implying an AD margin of 7%.

As in the previous example under US NME rules, the home-market prices for materials, labor, and electricity would be replaced by those in the surrogate country. In our example, we have an NME normal value of US$695, which implies a dumping amount of US$195 (or 39%). Once again, of the dumping amount obtained using NME methods 32% is due to using the NME methodology (39% less 7%).

CVD duty calculation

We now consider a complication stemming from the United States's use of ‘market benchmarks’ in its CVD analysis. We now allow the market-benchmark valuation to deviate from the surrogate-country values. Given that the USDOC basis for determining the ‘market benchmark’ is entirely different from the basis for picking a surrogate country, this mismatch often occurs. For example, while the surrogate country might value the raw materials at US$520 (used for the AD calculation), the market benchmark might value those same raw materials at US$575 (used for the CVD calculation).

In this example, the subsidies are determined to have produced a benefit of US$215 (as compared to US$160 in the first example). As a result, the CVD margin is larger (43%) than the dumping amount. Despite this mismatch, double remedies occur. The CVD margin can be decomposed into the part that is due to the use of NME methods when computing the dumping amount (32%) and the part that is due to the mismatch between the surrogate-country and benchmark valuation (11%).

In this example, the AD remedy alone is sufficient to make the destination price equal to the normal value (US$695). When the unadjusted CVD is also levied, the destination price rises to US$910.

4.2.5 Caveats

The intention of the US NME method and US CVD is the same – to purge the effects of government involvement on prices. We believe the AB could have used Article 19.3 of the SCM Agreement to definitively find the US practice inconsistent. Given the United States's NME methodology, we believe that some form of double remedies are automatic. The real issue is not if double remedies will occur under the NME method but rather how much occurs.

There are three possible qualifications to this conclusion. First, one might be concerned that surrogate-country producers are also benefiting from subsidies. While this might be a valid concern for NME methods used by other WTO members, we do not believe it is relevant for the United States. According to USDOC procedures, the surrogate country(ies) is (are) chosen because (i) they are comparable with the NME and (ii) because they are unsubsidized. Under USDOC procedures, a country with subsidization in the relevant input market would not be selected as a surrogate country.

Second, one might be concerned that the Chinese producers have such a dominant role on the world market of the product concerned that their (subsidized) prices have depressed prices on the world market or, at least, in the surrogate country. Again, we believe this concern is generally not applicable to the US situation given USDOC procedures which construct normal value using surrogate costs. We stress, however, that this conclusion hinges on the fact that the United States uses the factors-of-production methodology. While the NME's subsidy does not affect surrogate-country values because of the United States's factors-of-production approach, it could affect NME surrogate-country normal values used by other WTO members. For example, the EU will choose a surrogate country and then normally use the prices in that country. In such cases, the concern about the possibility of China's subsidized prices depressing prices in the surrogate country might be legitimate.

Third, there is a concern that the profit margin used by the USDOC might be affected by the subsidy. That is, the subsidies might allow the export prices charged by the Chinese firms to be lower than they would otherwise be, which in turn might lower the profit rate in the surrogate country. Thus, even though surrogate values are used, the ADD might not fully capture the effects of the subsidy. This is a valid concern; however, it was not part of the United States's argument to the AB.

4.2.6 Concluding thoughts on double remedies

Based on the foregoing analysis, we agree with the AB's conclusion that Article 19.3 of the SCM Agreement prohibits the imposition of concurrent AD and CVD duties which offset the same subsidization twice. However, we feel the AB could have relied on this Article to find the United States's simultaneous use of AD and CVD remedies (when the United States's NME methodology is used) illegal tout court. Instead, the AB opted for a broader determination and concluded that double remedies are ‘likely’ to occur and refrained from putting ‘likely’ into context. This leaves open the possibility for the United States to establish that, in other NME cases, concurrent duties in fact will not offset the same subsidization twice.

We believe the AB's approach will likely open the door to additional double-remedies disputes in future years. The AB failed to adequately characterize when or if double remedies would occur, and the AB's measurement concerns are in fact not limited to the NME method. The AB focused on the issue ‘whether and to what extent domestic subsidies have lowered the export price of a product and … whether the investigating authority has taken the necessary corrective steps to adjust its methodology to take account of this factual situation’.Footnote 73 It seems to us that this focus is misplaced because the same question could then be raised with regard to Article VI:5, thereby creating a significant loophole in the applicability of that provision. Similarly, the question now exists why investigating authorities are not measuring double remedies when other methods are used to compute normal value. Where domestic prices are not used as the benchmark for calculating normal value and the impact of the subsidies is therefore effectively ignored, in principle there will be double remedies unless the investigating authority can show that the alternative normal value (whether surrogate country or constructed value-based) is also subsidized or influenced by subsidization.

As an aside, it is noted that the AB did not address the issue whether double remedies must be taken into account when calculating the dumping/subsidies margin, and indeed Article 19.3 SCM Agreement would not provide a legal basis for that as it deals with the levy of countervailing duties. As US–AD and CVD (China) targeted US cases and the United States does not use the lesser-duty rule, ADDs are based on the dumping margins and therefore the margins found and duties are the same. The distinction is therefore irrelevant. However, the difference may be material in cases involving countries that do use a lesser-duty rule, such as the EU.Footnote 74 This is all the more so where the target of the investigations is China, and ADDs then often are based on the (lower) injury margins. The EU practice is to deduct the CVD from the ADD and, in cases where the duties are based on the injury margin,Footnote 75 to deduct the CVD from the injury margin that forms the basis for the imposition of the ADD. Therefore, at the stage of the duty collection, there are no double remedies. On the other hand, the EU does not make any adjustment at the stage of calculating the dumping and subsidy margins. This means that at least one inflated margin will be presented to the public, thereby feeding the perception in some quarters that Chinese producers benefit from high subsidies allowing them to dump their products in other markets.

4.3 The ‘public body’ determination

Contrary to dumping, which is a practice of private parties, subsidization always involves not only the private sector, which will benefit from the subsidization, but also the government, which makes a financial contribution to confer that benefit. Indeed, this is clear from the very start of the SCM Agreement, which provides in Article 1.1(a)(1) that a subsidy shall be deemed to exist if ‘there is a financial contribution by a government or any public body within the territory of a member (referred to in this Agreement as “government”)’. The dispute on this point involved the question whether the USDOC had appropriately determined that Chinese SOEs and SOCBs constituted public bodies within the meaning of this Article. Because of the pervasiveness of SOEs and SOCBs in the Chinese economic system, this finding is of significant importance not only as a matter of substance but also on purely procedural grounds, as it allows investigating authorities to solicit information on a wide range of Chinese entities in a CVD investigation, thereby significantly increasing the workload for the respondents, i.e. not only the producers under investigation but also the Chinese government itself, as well as the likelihood of findings based on facts available, particularly in cases where investigating authorities treat noncooperation by SOCBs and SOEs, which are legally independent from the government, as ‘non-cooperation’ on the part of the government. Not surprisingly, therefore, China challenged the approach of the USDOC, which had tended to focus principally on majority ownership by the government of the entities involved and which was essentially condoned by the Panel, which had defined a public body as any entity controlled by the government.

The AB considered this approach too simplistic and held that a public body within the meaning of the SCM Agreement must be an entity that possesses, exercises, or is vested with governmental authority. Whether the government ‘controlled’ an entity might be a relevant consideration, but it could not be a dispositive one. In completing the analysis, the AB then considered that the USDOC had improperly determined that the SOE input suppliers (producers of steel, rubber, and petrochemical inputs) constituted public bodies, but upheld the USDOC's findings with respect to the SOCBs on the ground that such findings were based on evidence not only of government control, but also of the SOCBs having effectively exercised certain governmental functions.

Thus, as reported by the AB, the USDOC had considered the following elements with regard to the SOCBs:

(i) ‘near complete state-ownership of the banking sector in China’; (ii) Article 34 of the Commercial Banking Law, which states that banks are required to ‘carry out their loan business upon the needs of [the] national economy and the social development and under the guidance of State industrial policies’; (iii) record evidence indicating that SOCBs still lack adequate risk management and analytical skills; and (iv) the fact that ‘during [that] investigation the [USDOC] did not receive the evidence necessary to document in a comprehensive manner the process by which loans were requested, granted and evaluated to the paper industry’.Footnote 76

As regards the SOE input suppliers, it must be highlighted that the AB ruled against the United States essentially on evidentiary grounds. Therefore, the ruling does not preclude the United States from qualifying SOEs as public bodies in the future; it merely requires the United States to shift the focus of its analysis to whether the SOEs possess, exercise, or are vested with governmental authority. The United States in fact might comply with this by examining the five factors that it normally analyses in order to determine whether an entity qualifies as a public bodyFootnote 77 and which are:

(i) government ownership;

(ii) government presence on the board of directors;

(iii) government control over activities;

(iv) pursuit of governmental policies or interests; and

(v) whether the entity was created by statute.Footnote 78

Ahn has rightly drawn attention to the AB explaining that ‘whether the functions or conduct are of a kind that are ordinarily classified as governmental in the legal order of the relevant member may be a relevant consideration for determining whether or not a specific entity is a public body’.Footnote 79 He considers that this may complicate a finding of ‘public body’ ‘since the governmental roles “in the legal order” of China tend to be more intrusive’.Footnote 80

4.4 De jure specificity in lending and regional specificity in land-use rights

In order for subsidies to be countervailable, they must be specific. Article 2 SCM Agreement, titled ‘specificity’, contemplates two types of specificity: sectoral specificity in Article 2.1 and regional specificity in Article 2.2. Sectoral specificity, in turn, can be found to exist de jure (Article 2.1(a) and (b))Footnote 81 or de facto (Article 2.1(c)).

De jure specificity

The AB considered that de jure specificity within the meaning of Article 2.1(a) can be found only ‘if the limitation on access to the subsidy to certain enterprises is express, unambiguous, or clear from the content of the relevant instrument, and not merely “implied” or “suggested”’.Footnote 82 On the other hand, the AB considered that the limitation on access could relate to the financial contribution, the benefit, or both.Footnote 83

For purposes of implementation of the 11th Five-Year Plan, which ran from 2006 to 2010, the Chinese State Council distinguished between four categories of projects/industries, i.e. encouraged, restricted, eliminated, and permitted. The projects/industries falling within the first three categories were further described in the Guiding Catalogue of the Industrial Restructuring, while all other projects/industries were considered to belong to the permitted category, provided that they were legal. The permitted category is therefore a residual category. China argued that SOCBs provided financing not only to the 539 projects/industries in the encouraged category but also to the vast permitted category. The AB rejected this argument on evidentiary grounds,Footnote 84 thereby perhaps leaving open the door for a future revisit of this issue.

China had also argued that the encouraged category was so wide as to preclude a finding of subsidization to ‘certain enterprises’, but the AB found that neither the USDOC nor the Panel had decided the specificity issue on this basis alone, but rather on the basis of the totality of the evidence available at the central, the provincial, and the municipal levels.Footnote 85