Suicidal thoughts and behaviours in adolescence

Despite national and international prevention efforts aimed at reducing suicide risk, the rate of suicide still continues to rise globally.Reference Alicandro, Malvezzi, Gallus, La Vecchia, Negri and Bertuccio1 Suicidal thoughts and behaviours typically emerge during adolescence, and their incidence rates rise sharply from childhood to adolescence.Reference Hawton, Saunders and O'Connor2 Suicide is the second leading cause of death for young people between 10 and 24 years of age.3,4 To better target prevention and intervention efforts, we must increase our understanding of risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviours in children and adolescents.

Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviours in adolescence

Two studies have investigated risk factors associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviours in a very large sample of children between the ages of 9 and 11 (n = 11 875) in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study.Reference Janiri, Doucet, Pompili, Sani, Luna and Brent5–Reference Volkow, Koob, Croyle, Bianchi, Gordon and Koroshetz7 DeVille et alReference DeVille, Whalen, Breslin, Morris, Khalsa and Paulus6 examined social–environmental factors using generalised linear mixed-effects models and revealed that higher levels of family conflict was associated with suicidal ideation and low parental monitoring was associated with both ideation and attempt. Janiri et alReference Janiri, Doucet, Pompili, Sani, Luna and Brent5 examined a broader range of potential risk and protective factors for suicidality using logistic regression and also showed that higher levels of family conflict was a risk factor for suicidality, the presence of child psychopathology and longer weekend screen time were also found to be risk factors, whereas greater parental supervision and positive school involvement were protective factors.

The findings that poor family coherence and support are associated with suicidal ideation in children are in line with the interpersonal–psychological model and the integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behaviour, in which the feeling of being alone and non-supported (thwarted belongingness) is an important risk factor for suicidal ideation and attempt.Reference Ribeiro and Joiner8,Reference O'Connor9 However, sociodemographic and clinical factors that have been identified previously to be associated with suicide thoughts and behaviours have not led to improved prediction of suicide thoughts or behaviours.Reference Franklin, Ribeiro, Fox, Bentley, Kleiman and Huang10 Therefore, there is a need for research into novel measures associated with suicide thoughts and behaviours such as genetics or regional brain activity that have been shown to play a role in these thoughts and behaviour in adolescents.Reference Vargas-Medrano, Diaz-Pacheco, Castaneda, Miranda-Arango, Longhurst and Martin11 In addition, these studies have not examined whether a combination of factors, instead of examining associations per risk factor, distinguishes children with and without suicidal thoughts or behaviour. Combining different types of risk factors may improve classification over use of individual risk factors.

Aims

To address these gaps, we examine whether a combination of a broad range of traditional risk factors (sociodemographic, physical health, social–environmental, clinical psychiatric characteristics) and novel risk factors (cognitive, neuroimaging and genetic characteristics) in almost 6000 unrelated children in the ABCD study could together differentiate children with a lifetime history of suicidal thoughts and/or suicide attempt and two control groups. As a large number of children in the suicidal thoughts and behaviour group also have a psychiatric disorder, the control groups were: (a) children without psychiatric disorder (healthy controls), (b) children with psychiatric disorders but no history of suicidal thoughts or behaviour (clinical controls). To this end, we used binomial penalised logistic regression and a feature selection approach, which can determine which type of measures contribute most to the classification of suicide thoughts or behaviours.

In addition to examining risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviours, it is important to identify factors that distinguish between individuals who only think about suicide (suicidal ideation) and those who attempt suicide (see for exampleReference Klonsky and May12,Reference Wetherall, Cleare, Eschle, Ferguson, O'Connor and O'Carroll13 ). This is relevant as it has been shown that only a third of individuals with suicidal thoughts actually attempt suicideReference Nock, Borges, Bromet, Alonso, Angermeyer and Beautrais14 and the identification of factors that differentiate these individuals may further inform targeted prevention and intervention efforts. Therefore, as a final aim, we examined which factors differentiated children with (a history of) suicidal ideation, but no history of suicidal behaviour, and those that have attempted suicide during their lives.

Method

Participants

All data included in this study were collected as part of the ABCD study (Annual Release 2.1; https://nda.nih.gov/abcd). Data were drawn from the baseline measurement of the ABCD study, which included data from 11 875 children between the ages of 9 and 11 assessed at 22 sites across the USA. The recruitment method and inclusion and exclusion criteria of the ABCD study are described elsewhere.Reference Volkow, Koob, Croyle, Bianchi, Gordon and Koroshetz7 All adolescents provided written assent and their parents provided consent. The Institutional Review Board of the University of California at San Diego approved the study protocol and data collection and is responsible for ethical oversight.

In the current study, we only included unrelated children, leading to a sample size of 9985 children (see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Figure 1; available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2022.7). In addition, nine children were excluded because of missing sociodemographic data, and 4000 children were excluded because of missing neuroimaging data or excluded as a result of the low quality of neuroimaging data (as suggested by the ABCD team). This resulted in a total sample size of 5885 children for the current analysis (50% female, 67% White).

Definition of outcome groups

Suicidal thoughts and behaviours (interrupted, aborted or actual suicide attempt) and psychiatric diagnoses were assessed using the child-and parent-reported version of the computerised Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for DSM-5 (K-SADS-5).Reference Kobak, Kratochvil, Stanger and Kaufman15 As previous findings showed low correspondence between parent- and child-reported suicide thoughts or behaviours in the ABCD sample,Reference Janiri, Doucet, Pompili, Sani, Luna and Brent5 we created two suicide thoughts or behaviours outcome variables, one for each (see Supplementary Note 2 for more details on group definitions). Children with comorbid psychiatric disorders were not excluded from the suicide thoughts or behaviours group. The definitions for the healthy control and clinical control groups were the same across parent and child outcome variables, however, because of differences in the suicide thoughts or behaviours outcome, the sample of the healthy control and clinical control groups also differed.

For the parent-reported suicide thoughts or behaviours outcome variable, we created three groups based on the K-SADS-5 diagnostic information:

(a) healthy control group (no parent-reported or child-reported psychiatric diagnosis was present and no parent-reported lifetime history of suicidal thoughts and behaviour; n = 2415);

(b) clinical control group (a parent-reported or child-reported psychiatric diagnosis was present, but there was no lifetime parent-reported history of suicidal thoughts or behaviour; n = 2976);

(c) suicide thoughts or behaviours group (lifetime parent-reported suicidal thoughts or behaviour was reported; n = 494).

The child-reported suicide thoughts or behaviours outcome variable included the following three groups:

(a) healthy control group (no parent-reported or child-reported psychiatric diagnosis was present and no child-reported lifetime history of suicidal thoughts or behaviour; n = 2367);

(b) clinical control group (a parent-reported or child-reported psychiatric diagnosis was present, but there was no lifetime child-reported history of suicidal thoughts or behaviour; n = 2985);

(c) suicide thoughts or behaviours group (lifetime child-reported suicidal thoughts or behaviour was reported; n = 528).

In addition, ancillary analyses were performed on the individuals that were in the same group according to both the parent and child outcome variables (see Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Table 3).

For secondary analyses, we created two additional outcome variables to distinguish children with lifetime suicidal thoughts (ideation) from children with a history of suicidal behaviour (attempt). The child-reported outcome variable included 461 children with self-reported suicidal ideation but no history of attempt and 67 children with a self-reported history of suicide attempt. The parent-reported suicide ideation and suicide attempt outcome variables included 464 children with suicidal ideation but no history of attempt, and 30 children with a history of suicide attempt (see Supplementary Note 4 for more details on group definitions).

Risk factors

Seven sociodemographic, 13 physical health, 28 social–environmental, 56 clinical psychiatric, 14 cognitive functioning, 88 neuroimaging and five genetic variables were included, based on available literature, as classifiers of group status (for a detailed overview of all included measures please see Supplementary Note 5 and 6, and Supplementary Table 1).

Statistical analysis

Training and independent validation data-sets

In order to perform the binomial penalised logistic regression analysis, a training data-set, consisting of two-thirds of the data, and a validation data-set (or hold-out sample), consisting of one-third of the data, were created by randomly splitting the data according to the data collection site to ensure the generalisation of model performance to independent sites (see Fig. 1). When the groups were based on the child-reported suicide thoughts or behaviours the training data-set consisted of 4168 children and the validation data-set of 1712 children (see Supplementary Table 2). The training data-set based on parent-reported suicide thoughts or behaviours included 4172 children and the validation data-set 1713 children.

Fig. 1 Flow chart to describe the analysis procedure. The ABCD data was split into a training and test set.

The training set was used to do a penalised logistic regression in tenfold cross validation and repeat this ten times with four different combinations of the Lasso and Ridge penalty. Features that had a coefficient higher than 0 in 90% or more of the repeats were selected to create a Ridge logistic regression to differentiate groups. This Ridge model was then tested on the test data-set. In addition, the same procedure was repeated only including risk factors from one modality.

Classification of group status in the training set

Binomial penalised logistic regression analysis was performed using the package glmnet in R.Reference Friedman, Hastie and Tibshirani16 This was applied to a combination of all measures in the training set to distinguish between (a) the healthy control group; (b) the clinical control group and (c) the suicide thoughts or behaviours group.

The binomial penalised logistic regression builds a sparse model by adding a penalty that prevents overfitting. This approach combines two types of penalties or regularisations. A Ridge penalty shrinks coefficients, making their contribution to the model small, and a Lasso penalty forces some coefficients to zero, meaning that the feature is not selected for the model. A combination of the two penalties allows for feature selection as well as for features to have a small contribution to the model. Binomial penalised regression was performed with different penalties (alpha levels: 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1), varying between a Lasso penalty (alpha = 1) and a combination of Lasso and Ridge penalties (elastic net; alpha's between 0.25 and 0.75). Ten-fold cross validation was applied by dividing the training data-set into ten sets, and within each cross-validation fold, nine out of ten sets were combined to form the training set and one was used as the test set. This was repeated ten times. The glmnet package determined the optimal lambda value by identifying the lambda associated with the minimum Brier score. In each cross-validation fold we imputed missing values using the caret packageReference Kuhn17 in the test set and training set separately, in order to prevent data leakage.

Binomial analyses comparing two groups were run (healthy control versus clinical control, clinical control versus suicide thoughts or behaviours and healthy control versus suicide thoughts or behaviours groups). Binomial analyses were performed instead of multinomial analyses, as a set of clinical psychiatric measures were only non-zero in the clinical control and suicide thoughts or behaviours groups. As the suicide thoughts or behaviours group was smaller than the clinical control and healthy control groups, we undersampled these larger groups within each cross-validation fold to match the size of the suicide thoughts or behaviours group by randomly selecting participants from the healthy control and clinical control groups. In additional analyses we performed the abovementioned analyses again using a nested alpha function (please see Supplementary Note 7 for a description and the results).

The performance of the model was assessed using the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUROC). AUROC represents the proportion of times an individual from a positive class (for example suicide thoughts or behaviours group) is ranked below an individual from a negative class (for example healthy control group). In addition, sensitivity, specificity, average of the sensitivity and specificity (accuracy) were calculated. Permutation testing (by comparing the AUROC against the AUROC of the same procedure repeated 1000 with permuted group labels) was used to examine if the model performed significantly above chance level classification. To identify the features that contributed most to the classification model, the features that had a coefficient of more than zero in at least 90% of the subsamples were selected.

Generalisation to the independent validation set

The features that were selected in at least 90% of the subsamples at each alpha (0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 1.00) in the training data-set were used to classify group membership in the independent validation set. This validation set consisted of seven sites from the ABCD study that were kept separate to ensure independence. This analysis was done to test the generalisability of the classification model to independent sites and participants. The selected features at each alpha were used in a Ridge logistic regression in the whole training set; this model was then tested on the independent validation set.

Modality-specific classification

In order to examine the individual contribution of the different modalities to the classification of the suicide thoughts or behaviours groups, we repeated the aforementioned analysis, but only including specific types of measures, thus performing separate analyses for sociodemographic, physical health, social–environmental, clinical psychiatric, cognitive functioning, neuroimaging and genetic measures.

Factors that differentiate ideators from individuals who attempted suicide

To examine which factors differentiate between children with a history of attempt from those with suicidal ideation but no history of suicide attempt, the abovementioned binomial penalised logistic regression analysis was performed again with a different outcome variable. For this analysis, the data-set was again divided into a training set and validation set using the same site split as in the main analysis, and the same approach (including the binomial penalised logistic regression with cross validation, feature selection and Ridge regression) was used to test generalisability; however, only five folds were used because the sample size was smaller.

Results

Participant characteristics

Age, gender, lifetime psychiatric diagnosis and self-reported suicidal thoughts or behaviours are presented in Table 1 for the three groups (healthy controls, clinical controls and suicide thoughts or behaviours) based on child-reported and parent-reported suicidal thoughts or behaviours.

Table 1 Participant characteristics

ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; GAD, generalised anxiety disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Classification of suicide thoughts or behaviours group

Classification of suicide thoughts or behaviours group: cross-validation model performance

Results of the analysis using the child-reported suicide thoughts or behaviours group measures are presented in Table 2. AUROC values were highest when differentiating the healthy control and suicide thoughts or behaviours groups (0.80 across the different alpha levels), and were lowest for the comparison between healthy control and clinical control groups (AUROC 0.69, Supplementary Figure 2).

Table 2 Classification of suicide thoughts or behaviours groups (child-reported and parent-reported): results of binomial penalised logistic regression analysis

AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristics curve; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

A similar pattern was observed for the results of the analyses using the parent-reported suicide thoughts or behaviours group measures (see Table 2), with the highest AUROC observed for the healthy control versus suicide thoughts or behaviours comparison (0.81) and lowest for the healthy control versus clinical control comparison (range: 0.68–0.69). ROC curves, cross-validation curves and Brier scores are presented in the Supplementary Figures 3–5 and Supplementary Table 4.

Feature selection

Results of the feature selection analysis are presented in Supplementary Table 5 and 6 for the child-reported and parent-reported suicide thoughts or behaviours groups, respectively. Although the same measures were included in both analyses, the factors that distinguished the child-reported suicide thoughts or behaviours group from the clinical controls were family conflict, prodromal psychotic symptoms, impulsivity (UPPS-PReference Lynam, Smith, Whiteside and Cyders18 negative urgency and lack of planning subscales) and the CBCLReference Achenback and E19 depression subscale score. The factors that differentiated the clinical controls from the individuals in the parent-reported suicide thoughts or behaviours group included the CBCL depression subscales (anxious depression, DSM-5 depression), CBCL conduct disorder subscale score, CBCL internalising and externalising broad band scores and a history of mental health service use or treatment. Plots of the stability of each predictor within repeated cross-validation folds are presented in the Supplementary Figure 6. In addition, we examined the results using a stricter feature selection approach (see Supplementary Note 8 for a description and results).

Generalisation to the independent validation data-set

The AUROC in the independent validation data-set (seven separate ABCD sites) using the most contributing features selected (see above), was in line with the AUROCs achieved in the training data-set (see Supplementary Tables 7 and 8). Classifying healthy control versus suicide thoughts or behaviours groups, the AUROC ranged between 0.78 and 0.79 using the child-reported suicide thoughts or behaviours group measure and between 0.81 and 0.82 using the parent-reported suicide thoughts or behaviours group measure, using the features that were selected in the training data-set at different alphas. Classifying the healthy control versus clinical control groups, the AUROC ranged between 0.70 and 0.71 using the child-reported group measure and between 0.70 and 0.71 using the parent-reported measure. Finally, classifying the clinical control versus suicide thoughts or behaviours groups, the AUROC ranged between 0.70 and 0.71 when using the child-reported measure and between 0.70 and 0.71 when using the parent-reported measure.

Modality-specific classification

Results of these analyses are presented in Supplementary Table 9 and 10 for the child-reported and parent-reported suicide thoughts or behaviours group analyses, respectively. For both the classification of the child- and parent-reported suicide thoughts or behaviours group status, the clinical psychiatric (AUROC child-reported: 0.68; parent-reported: 0.77–0.78), physical health (AUROC range child-reported: 0.58–0.73; parent-reported: 0.63–0.77), cognitive functioning (AUROC range child-reported: 0.59–0.71; parent-reported: 0.53–0.64) and social–environmental factors (AUROC range child-reported: 0.62–0.74; parent-reported: 0.62–0.73) best classified suicide thoughts or behaviours groups, in contrast to neuroimaging (AUROC range child-reported: 0.50–0.52; parent-reported: 0.49–0.51), sociodemographic measures (AUROC range child-reported: 0.54–0.58; parent-reported: 0.53–0.61) and genetic characteristics (AUROC range child-reported: 0.51–0.57; parent-reported: 0.52–0.55).

Similar to the aforementioned results, the highest AUROC values were observed for the healthy control versus suicide thoughts or behaviours comparison. Statistical analyses of the performance of the different modalities can be found in Supplementary Note 9 and Tables 11 and 12.

Classification of ideators versus individuals who attempted suicide

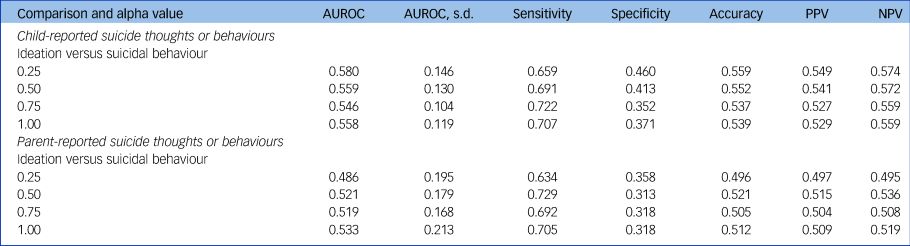

Results of the analysis used to classify child-reported suicidal ideation versus suicidal attempt are presented in Table 3. AUROC values varied between 0.55 and 0.58 across the different alpha levels. Results of the same analysis, but using the parent-reported group measure showed similar results (AUROC range: 0.49–0.53; see Table 3). As the results show that it is not possible to distinguish these two groups, no further feature selection or modality-specific classification was performed.

Table 3 Classification of suicidal ideation versus suicidal behaviour (child-reported and parent-reported): results of binomial penalised logistic regression analysis

AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristics curve; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

Discussion

Main findings

In a large sample of almost 6000 unrelated children, we examined whether a combination of non-biological (sociodemographic, physical health, clinical psychiatric, cognitive, psychosocial) and biological (neuroimaging and genetic) factors could differentiate healthy children, children with psychiatric disorder but no history of suicidal thoughts or behaviour, and children with a lifetime history of suicidal thoughts or suicide attempt. Binomial penalised logistic regression analysis showed that the suicide thoughts or behaviours group could be distinguished from the healthy control (AUROC range 0.80 child-report, 0.81 parent-report) and clinical control groups (0.71 child-report and 0.76–0.77 parent-report), but the ability to differentiate the clinical control and healthy control groups was less accurate (AUROC 0.69 child-report and 0.68–0.69 parent-report). These results may be explained by the fact that the children with most severe psychiatric symptoms may have been included in the suicide thoughts or behaviours group, thereby reducing the differences between the clinical control and healthy control groups.

Our model generalised to independent data (separate ABCD recruitment sites (AUROC range child-report: 0.70–0.79; 0.70–0.82 parent-report)). The analyses for groups based on parent- and child-reported measures were performed separately, as a recent studyReference Janiri, Doucet, Pompili, Sani, Luna and Brent5 showed low correspondence between parent-reported and child-reported measures of suicidal thoughts and behaviours in the ABCD study. The AUROCs of these analyses were very similar, as we were able to distinguish the groups based on both the parent- and child-reported measures. Children with a lifetime history of suicidal ideation could not be distinguished from those with a lifetime history of suicide attempt (AUROC range 0.55–0.58 child-report; 0.49–0.53 parent-report).

Predictive value

The classification of suicide thoughts or behaviours and identifying contributing risk factors are important aims in suicide research as it may help identify those at risk and help target prevention and intervention efforts. In this study, when discriminating the suicide thoughts or behaviours group from the clinical control group, the positive predictive value varied between 0.66 and 0.73, whereas the negative predictive value varied between 0.63 and 0.68. This means that around three out of ten children were misclassified as belonging to the suicide thoughts or behaviours group although they had no history of suicide thoughts or behaviours, and similarly, around three out of ten children were misclassified as belonging to the clinical control group although they did have a history of suicide thoughts or behaviours.

Although the PPV in our study is higher than observed in a meta-analysis that used psychological and biological risk instruments to predict suicidal behaviour, the sensitivity observed is lower than the sensitivity of existing suicide scales in predicting suicide attempt,Reference Lindh, Dahlin, Beckman, Strömsten, Jokinen and Wiktorsson20–Reference Carter, Milner, McGill, Pirkis, Kapur and Spittal22 and therefore our classification model is not yet sufficient to be used as a clinical decision tool. Risk assessment using traditional suicide scales may therefore outperform our multimodal prediction. Our findings are in line with three meta-analyses that showed that (a combination of) psychological or biological measures were limited in their ability to predict suicide or suicidal behaviourReference Runeson, Odeberg, Pettersson, Edbom, Jildevik Adamsson and Waern21–Reference Belsher, Smolenski, Pruitt, Bush, Beech and Workman23 showing that classification of suicidal thoughts and behaviours is complex, and adding to the current debate around precision medicine in suicide research (see for exampleReference Whiting and Fazel24).

Classification per modality

When the risk factors were divided into separate modalities to examine their unimodal predictive characteristics, the AUROC values for social–environmental, physical, cognitive and clinical psychiatric modalities were higher than the AUROC values for neuroimaging, genetic and sociodemographic modalities. This finding was in line with the strongest contributing features when all predictors were combined in one analysis, as these features were mainly from the social–environmental and clinical psychiatric categories. The functional magnetic resonance imaging-based measures included did not seem to contribute to the classification of children with suicide thoughts or behaviours.

In contrast to these findings, previous studies have found that functional brain alterations in the prefrontal cortex are related to suicide thoughts or behavioursReference Schmaal, van Harmelen, Chatzi, Lippard, Toenders and Averill25,Reference Gosnell, Fowler and Salas26 and contribute to the classification of youth who are suicidal.Reference Just, Pan, Cherkassky, McMakin, Cha and Nock27 However, our findings are consistent with a neuroimaging-specific evaluation of this same cohort, in which no association was found between suicidal thoughts and behaviours and functional neuroimaging measures.Reference Vidal-Ribas, Janiri, Doucet, Pornpattananangkul, Nielson and Frangou28 These discrepant findings between ABCD and other studies could potentially be explained by the younger age of participants in the ABCD study, the fact that ABCD is a population study or methodological issues that have been described elsewhere.Reference Bissett, Hagen, Jones and Poldrack29 In addition, the polygenic risk scores included in the analysis also did not contribute to classification, which is in line with previous studies that show that the polygenic risk score for major depressive disorder only explained a small part of the variation in self-injurious behaviour.Reference Maciejewski, Renteria, Abdellaoui, Medland, Few and Gordon30

Individual features that contribute to classification of suicide thoughts or behaviours

Most features that contributed to the model classifying the healthy control and suicide thoughts or behaviours groups also contributed when classifying the clinical control group from the healthy control group. When the suicide thoughts or behaviours group was differentiated from the clinical control group, family conflict, prodromal psychosis, severity of mental health symptoms and measures of impulsivity were among the features that contributed most to the model's predictions. These findings highlight the potential need for clinicians to consider alternative interventions, including family-based psychological interventions to decrease family conflictReference Weinstein, Cruz, Isaia, Peters and West31 or neuropsychological training to increase cognitive control and planning abilities; and emotional regulation skills, distress tolerance training or mindfulness-based interventions in order to decrease negative urgency and modulate impulsivity in individuals who are suicidal. Surprisingly, parent-reported child mental health service use predicted parent-reported suicide thoughts or behaviours, but not child-reported suicide thoughts or behaviours, further highlighting the low correspondence between parent- and child-reported suicide thoughts or behaviours.

Classification of ideation versus attempt

Understanding that children will experience suicidal thoughts or attempt suicide has important implications for suicide prevention and clinical practice.Reference Klonsky, Qiu and Saffer32 In this cross-sectional study, we were unable to differentiate children with suicidal thoughts from children with a history of suicidal behaviour, potentially suggesting a shared aetiology between ideation and attempt in this age group. A large study in 16-year-olds showed that, compared with adolescents with suicidal thoughts, those that attempted suicide were more often exposed to self-harm by friends or family members, were more likely to be diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder, more often were female, exposed to trauma, more impulsive and had specific personality characteristics (i.e. high sensation seeking and low conscientiousness).Reference Mars, Heron, Klonsky, Moran, O'Connor and Tilling33 A second large study conducted among adolescents and young adults showed that acquired capability, impulsivity, mental imagery about death and exposure to suicidal behaviour were more common in those who attempted suicide compared with ideators.Reference Wetherall, Cleare, Eschle, Ferguson, O'Connor and O'Carroll13

Meta-analyses showed that traumatic life events, history of abuse, drug use disorders and alterations in decision-making and impulsivity were more common in individuals who attempted suicide than ideators, whereas depression, alcohol use, hopelessness and sociodemographic variables did not differ between individuals who attempted suicide and ideators.Reference May and Klonsky34,Reference Saffer and Klonsky35 We were unable to include some of the aforementioned variables in our logistic regression model, which may explain why our classification performance was poorer than that observed in previous studies. The variables that contributed to the classification of the suicide thoughts or behaviours group from the clinical control group, were unable to distinguish ideation from an attempt, as they may be related to suicidal thoughts and behaviour in general, and do not differ between ideators and individuals who attempted suicide. In addition, only 67 children reported a history of suicide attempt and only 30 parents reported that their child had a history of suicide attempt, which may have limited our power to detect small effects. Finally, the young age of these participants may have added additional noise to the classification, as a larger fraction of the ideation group may attempt suicide in the future compared with studies with older participants.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to combine multimodal features to classify children with suicidal thoughts and behaviour from the clinical control and healthy control participants in the ABCD study, and builds on previous work by Janiri et al and DeVille et al.Reference Janiri, Doucet, Pompili, Sani, Luna and Brent5,Reference DeVille, Whalen, Breslin, Morris, Khalsa and Paulus6 Compared with these previous studies, the strengths of this study include the large sample size of unrelated participants, the availability of many different types of predictors, including clinical, sociodemographic, biological and cognitive measures, and the use of an ecologically valid control group consisting of children with a psychiatric disorder. An additional strength is rigorous validation using cross validation and an independent out-of-sample validation that avoids overly optimistic results because of overfitting in the training set. The findings need to be interpreted in the light of a few limitations, including the cross-sectional nature of the data.

First, longitudinal data collection for participants enrolled in the ABCD study is planned at 2-year intervals for a total of 10 years, and future studies may build on these baseline models to predict suicidal thoughts or behaviour throughout adolescence. Second, no measures of the severity or frequency of suicidal ideation or behaviour were available, which limited our ability to examine specific subgroups with varying suicidal severity. Third, both static (for example polygenic risk scores), early life (for example negative life events) and transient (for example psychiatric symptoms) factors were included as risk factors in the current study, as they can all contribute to risk for suicide thoughts or behaviours. Although static risk factors are unmodifiable and may not represent immediate targets for suicide prevention, they may be important for identification and classification of those at risk. In contrast, more dynamic risk factors may represent better direct targets for suicide prevention. Ecological monetary assessment lies at the dynamic end of the spectrum and could potentially detect risk in real time, and could therefore be considered in future studies. Fourth, the independent hold-out sample used in this study was a single random partition of the ABCD data. To ensure generalisability the model should be tested in yet another independent data-set, preferably a different data-set where similar measures were collected. Finally, in this study, we showed the limited contribution of biological measures to classification, however, we may have missed interesting associations as we included these measures as continuous measures across the entire range. Future studies on these biological measures could consider using a more sophisticated approach by first stratifying groups by certain clinical and/or biological characteristics and then selecting a classification model that would be based on this individual's characteristics.

Implications

In conclusion, although results of this study revealed modest classification of suicide thoughts or behaviours-based groups in children, which limits the use of this model as a clinical decision tool, this study did reveal risk factors for suicide thoughts or behaviours in children and points to potential treatment targets. Our study shows that social–environment (family conflict), cognitive (impulsivity) and clinical measures (such as severity of prodromal psychosis symptoms, severity of depression) differentiate children with and without a history of suicidal thoughts and behaviour. More studies in a larger sample of individuals who have attempted suicide are needed to confirm whether the factors identified in our study differentiate those with ideation from those with a history of attempt and prospectively predict subsequent suicidal behaviour. In addition, future studies could determine whether including additional variables (such as suicide-related measures) improves classification. This work highlights the need for clinicians to monitor children who present with multiple risk factors and may inform future social–environmental interventions that may contribute to suicide prevention in at-risk children.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2022.7.

Data availability

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive DevelopmentSM (ABCD) study (https://abcdstudy.org), held in the NIMH Data Archive (NDA).

Author contributions

L.S.v.V., Y.J.T.: conceptualised the study, conducted the data analysis, and wrote the majority of the manuscript. R.D.: contributed to the analysis of the data and critically revised the manuscript. A.C.: contributed to the analysis and assisted in writing the manuscript. A.A.-P., J.A.R., N.J., M.E.R.: critically revised the manuscript. L.S.: conceptualised the study, provided guidance for interpreting the findings, and critically revised the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the MQ Brighter Futures Award MQBFC/2 (LS) and the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MH117601 (L.S., N.J.). L.S. is supported by a NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (1140764). Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive DevelopmentSM (ABCD) study (https://abcdstudy.org), held in the NIMH Data Archive (NDA). This is a multisite, longitudinal study designed to recruit more than 10 000 children age 9–10 and follow them over 10 years into early adulthood. The ABCD study is supported by the National Institutes of Health and additional federal partners under award numbers U01DA0401048, U01DA050989, U01DA051016, U01DA041022, U01DA051018, U01DA051037, U01DA050987, U01DA041174, U01DA041106, U01DA041117, U01DA041028, U01DA041134, U01DA050988, U01DA051039, U01DA041156, U01DA041025, U01DA041120, U01DA051038, U01DA041148, U01DA041093, U01DA041089, U24DA041123, U24DA041147. A full list of supporters is available at https://abcdstudy.org/federal-partners.html. A listing of participating sites and a complete listing of the study investigators can be found at https://abcdstudy.org/consortium_members/. ABCD consortium investigators designed and implemented the study and/or provided data but did not necessarily participate in analysis or writing of this report. This manuscript reflects the views of the authors and may not reflect the opinions or views of the NIH or ABCD consortium investigators. The ABCD repository grows and changes over time. The ABCD data used in this report came from 10.15154/1520786. DOIs can be found at nda.nih.gov.

Acknowledgements

A preprint of this manuscript has previously been published on MedRxiv.

Declaration of interests

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.