Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) poses a global threat. Disease severity varies widely from mild (81%), requiring hospitalization (12%), to death (1.8–3.4%) [Reference Bialek1].

The growing number of US COVID-19 cases is expected to tax the capacity of health care delivery systems. Analysis of clinical characteristics at time of patient presentation associated with disease severity is immediately useful. Recognizing the rapid utility of such data, we evaluated clinical characteristics and disease course of patients with confirmed COVID-19 at Stanford Hospital.

Methods

With approval of the Stanford Institutional Review Board, patient charts were analyzed if they were diagnosed with COVID-19 by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, received care at Stanford Hospital by March 16, 2020, and had past medical history documentation. Statistical analyses were conducted in Microsoft Excel and R.

Results

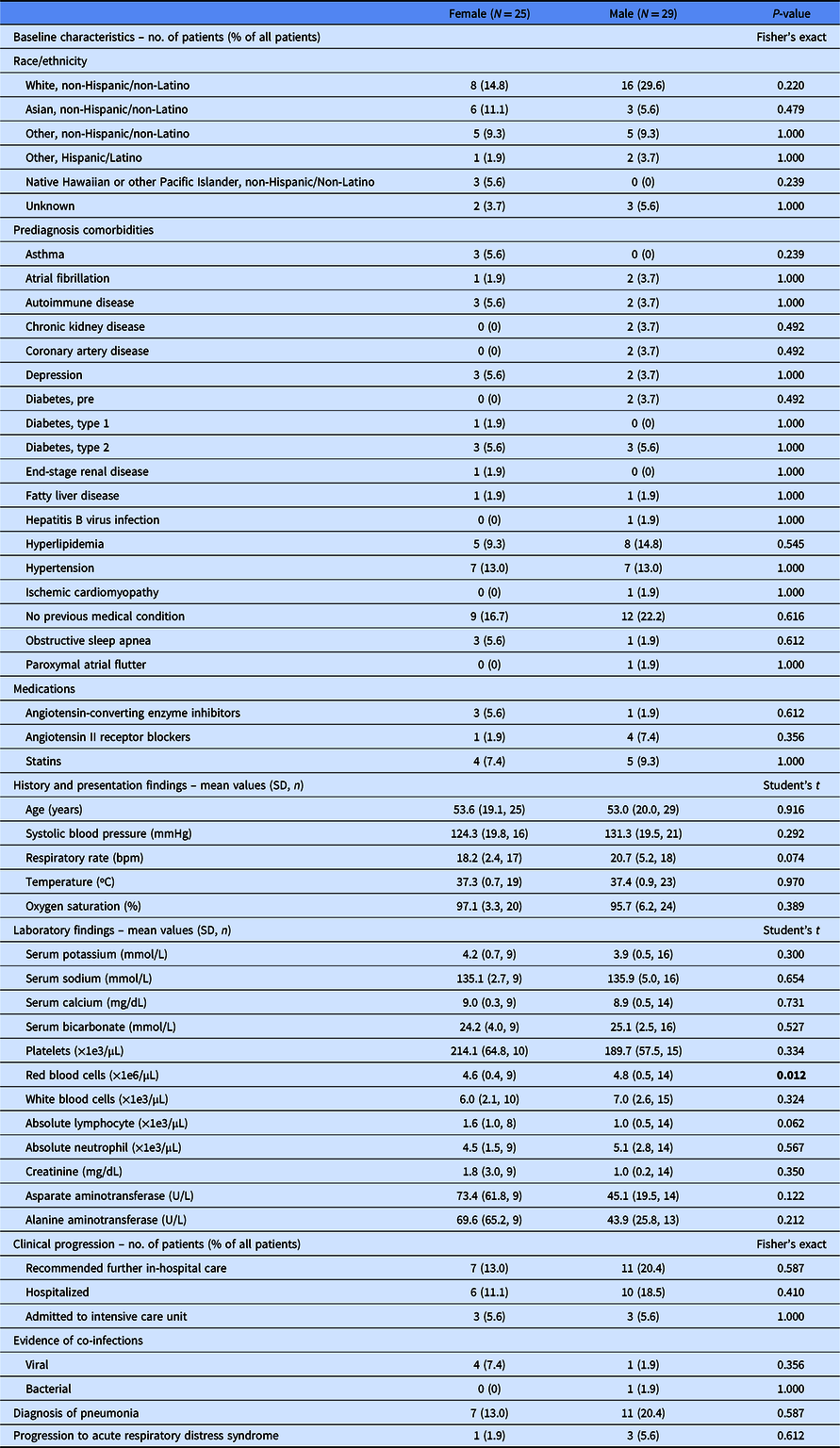

Of 54 patients analyzed, the median age was 53.5 years (interquartile range, 32.75; range, 20–91), 53.7% were male, 18 were inpatients, and 36 were outpatients (Table 1). Based on chart documentation of past medical history, 14 had hypertension, 13 had hyperlipidemia, and 7 had diabetes (6 type 2, 1 type 1).

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of 54 patients with COVID-19 in California

N, total patient number in category; n, patients in category with data available; SD, standard deviation.

The statistically significant values are in bold.

Consistent with previous COVID-19 reports, the most common prediagnosis comorbidity in 24 patients (25.9%) was hypertension; this rate does not significantly differ from the US prevalence (Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.671) [Reference Wu2,Reference Fryar3]. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I) or angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) use in nine patients (16.7%) was also not significantly different from the US prevalence (Fisher’s exact test, P = 1.000) [Reference Benjamin4].

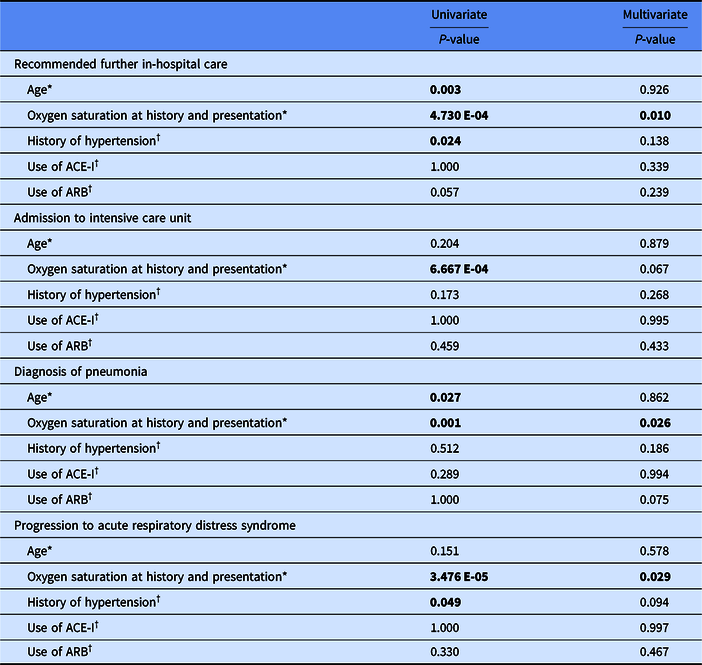

In univariate analysis, age, lower oxygen saturation at initial examination, and hypertension were significantly associated with recommendation for further hospital care, lower oxygen saturation was associated with admission to intensive care unit (ICU), age and lower oxygen saturation were associated with diagnosis of pneumonia, and lower oxygen saturation and hypertension were associated with progression to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Table 2). Use of ACE-I or ARB was not significantly associated with recommendation for further hospital care, admission to ICU, diagnosis of pneumonia, or progression to ARDS. When analyzed by logistic regression to control for age, the only factor independently significantly associated with recommendation for further in-hosptial care, diagnosis of pneumonia, and progression to ARDS was initial oxygen saturation measurement as a continuous variable.

Table 2. Correlates of clinical progression

ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers.

The statistically significant values are in bold.

* Two-tailed homoscedastic Student’s t-test for univariate analysis.

† Fisher’s exact test for univariate analysis.

Discussion

Clinical characteristics of US COVID-19 patients and factors from initial presentation that associate with disease severity were identified. Lower oxygen saturation at presentation was independently significantly associated with measures of disease severity and thus may serve as a useful indicator of potential disease progression. Additionally, history of hypertension predisposed patients to worse outcomes such as ARDS, although not independently of age, consistent with previous reports [Reference Wu2].

Several factors, including age-related changes in the immune system and other physiological processes, could contribute to COVID-19 disease severity. While hypertension is associated with COVID-19 morbidity, it is not independent of age; thus further study is needed to elucidate the extent to which hypertension and/or dysregulation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) contribute to COVID-19 pathogenesis. The idea that RAAS dysregulation may influence disease progression warrants further exploration into the usefulness of ACE-I and/or ARB therapies in COVID-19 management.

The potential role of the RAAS system in COVID-19 pathogenesis stems from mounting sequence and structural evidence indicating entry of SARS-CoV-2 via interaction of its spike protein with its human host receptor ACE2 [Reference Wan5]. It is difficult to predict the effects of RAAS blockade in treatment of COVID-19, as it may increase expression of ACE2, with known anti-inflammatory and pulmonary protective properties, yet simultaneously promote viral entry [Reference Ferrario6]. However, RAAS blockade may also increase soluble ACE2, which could serve as a decoy receptor protecting against viral entry.

In our study, history of ACE-I or ARB use did not affect diagnosis rate or predispose patients to worse disease outcomes. However, our study is underpowered to draw definitive conclusions from such negative data. We hope these initial findings motivate larger studies intended to characterize RAAS blockade in the COVID-19 setting.

Limitations of this study include lack of some data on disease progression due to retrospective design and potential selection bias of patients with severe disease more likely to have SARS-CoV-2 testing and extensive charting. However, these US data are immediately clinically relevant given the rapidly evolving pandemic and will help clinicians identify and treat patients most at risk of severe disease.

Acknowledgements

We thank Arjun Rustagi, MD, PhD, Vivek Bhalla, MD, and Glenn Chertow, MD, MPH of Stanford University School of Medicine, USA, and Andrew Michael South, MD, MS of Wake Forest School of Medicine, USA for helpful discussions. No compensation was received for their roles in the study.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.