‘There will be more rejoicing in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who do not need to repent’ (Luke 15:7)

Stigma is a social construction that devalues people because of a distinguishing characteristic or mark (Reference Biernat and DovidioBiernat & Dovidio, 2000). The World Health Organization (WHO) and World Psychiatric Association (WPA) recognise that stigma attached to mental disorders is strongly associated with suffering, disability and poverty (Reference Corrigan, Markowitz and WatsonCorrigan et al, 2003). Studies show that negative attitudes towards people who are mentally ill are widespread (Reference Crisp, Gelder and RixCrisp et al, 2000). The media generally depicts such people as violent, erratic and dangerous (Reference Granello, Pauley and CarmichaelGranello et al, 1999). Stigma is a major barrier to treatment-seeking behaviour (Reference ApplebyAppleby, 1999).

The Royal College of Psychiatrists’ ‘Changing Minds’ campaign aimed to promote positive images of mental illness, challenge misrepresentations and discrimination, and educate the public as to the real nature and treatability of mental disorder (Reference Crisp, Gelder and RixCrisp et al, 2000). The large survey by Crisp et al (Reference Crisp, Gelder and Goddard2005) showed that people with schizophrenia, alcoholism and drug addiction were the most stigmatised of all those with mental disorder. We chose to study methods of reducing stigma towards the conditions that clearly evoked the most negative attitudes.

This study aims to devise a simple, practical technique to reduce stigmatised attitudes of the general public towards the mentally ill through leaflets that could be used on a population basis or targeted to specific groups such as landlords or employers.

Method

Sample

The sample was drawn from a panel of 400 participants from the UK general population, previously recruited using direct mail-shots and advertisements in local newspapers for part of a previous study (Validation of Attitude to Mental Illness Questionnaire; Reference Luty, Fakuda and UmohLuty et al, 2006). The current study is part of a larger study to validate the Fear of Addiction Questionnaire. The local research ethics committee granted ethical approval.

Instrument

The five-item Attitude to Mental Illness Questionnaire (AMIQ; Reference Luty, Fakuda and UmohLuty et al, 2006) is a brief, self-completion questionnaire. Respondents read a short vignette describing an imaginary patient and answer five questions (Appendix 1). Individual questions are scored on a five-point Likert scale (maximum +2, minimum –2) with blank questions, ‘neutral’ and ‘don't know’ scored zero. The total score for each vignette ranges between –10 and +10.

Study design

Participants were block-randomised using the randomisation function of the Stats Direct Statistical Package, version 2.4 (www.statsdirect.com). The control group received simple descriptions of cases of schizophrenia, opiate dependence or alcoholism (Appendix 2). The experimental group received ‘upbeat’ descriptions of hypothetical patients in remission (Appendix 2). Experimental group vignettes contained a photograph of a professional-looking male model identified by a relevant fictional name. No such pictures were attached to the vignettes for the control group.

Data analysis

Randomisation, correlation coefficients and non-parametric (Mann-Whitney and Wilcoxon) tests were used to generate and compare differences in subgroups using the Stats Direct statistical package.

Results

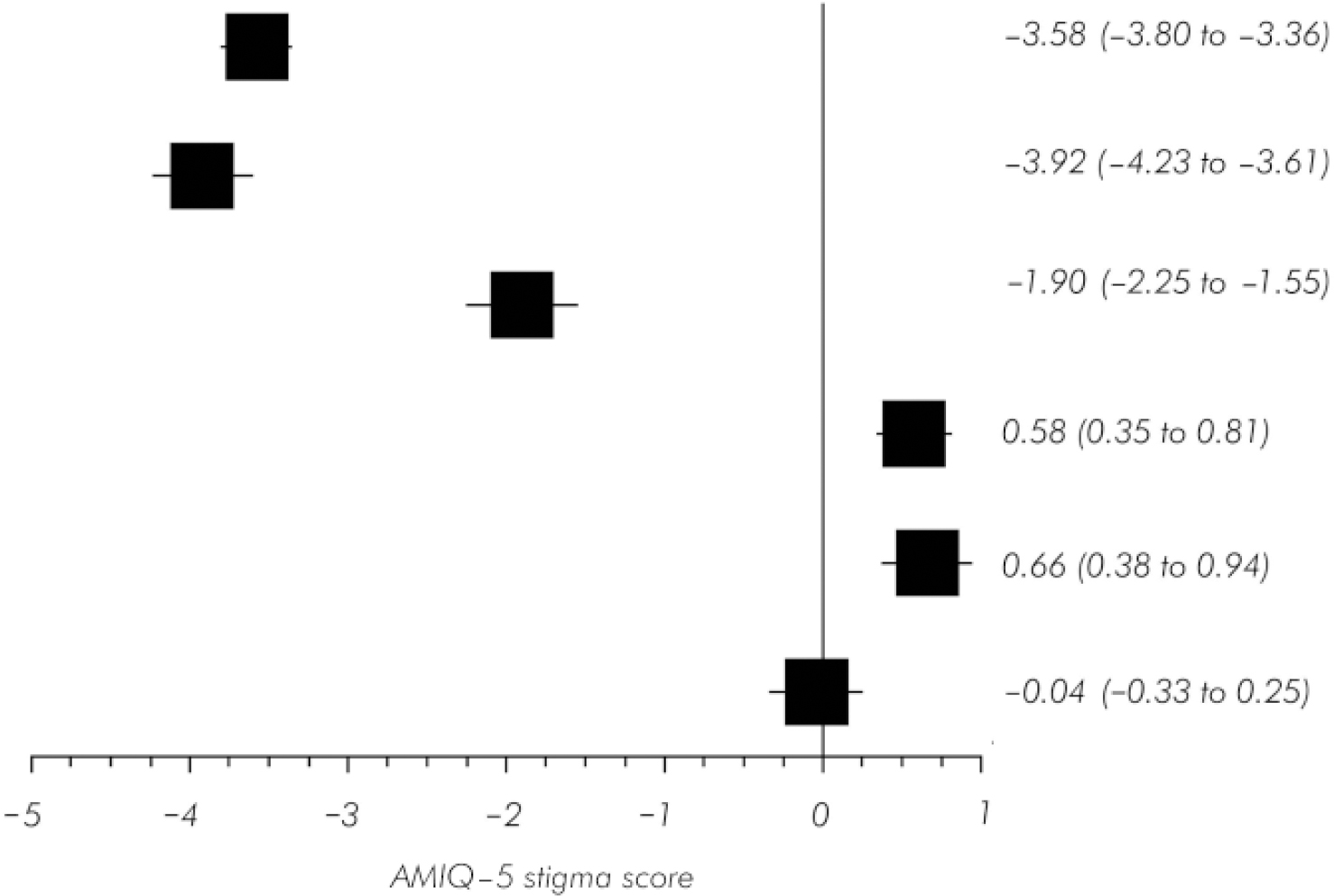

Results were received for 310 (77%) participants, with 155 in the control group and 148 in the experimental group (seven questionnaires were not completed). Overall, 26% were men; the mean age was 47.9 years (s.e.=1.5); 55% of the sample were in paid employment and 17% were retired. There was no significant difference in age or other demographic factors between the experimental group (mean age 49.5 years, s.e.=1.6; 24% male) and the control group (mean age 46.3 years, s.e.=1.5; 29% male). Table 1 indicates that the leaflet with the photograph produced a large, statistically significant reduction in stigmatised attitudes towards people with heroin dependence (effect size 1.53, CI 1.23-1.82, P<0.0001; median change 4 units) and alcohol dependence (effect size 1.41, CI 1.12-1.70, P<0.0001; median change 4 units) but a lesser reduction towards people with schizophrenia (effect size 0.54, CI 0.27-0.80, P=0.0002; median change 2 units) (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Attitude to Mental Illness Questionnaire1 scores following distribution of photo leaflets

| Disorder | Experimental group score (n=148) Mean (s.e.) | Control group score (n=155) Mean (s.e.) | P 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opiate use | 0.58 (0.23) | –3.58 (0.22) | <0.0001 |

| Alcoholism | 0.66 (0.28) | –3.92 (0.31) | <0.0001 |

| Schizophrenia | –0.04 (0.29) | –1.90 (0.35) | 0.0002 |

There was no difference between groups with respect to the control questionnaire (which was distributed to both groups) at 4-week follow-up (233 responses received; response rate 78%). Mean AMIQ scores for opiate dependence were –3.79 (s.e.=0.34, n=115) in the control group v. –3.37 (s.e.=0.27, n=118) in the experimental group (P=0.4447); for schizophrenia they were –1.78 (s.e.=0.36) in the control group v. –1.36 (s.d.=0.32) in the experimental group (P=0.7333). The AMIQ scores for alcoholism were –3.59 (s.d.=0.32) in the control group v. –3.65 (s.d.=0.30) in the experimental group (P=0.581). There was no difference in responses with respect to the age or gender of respondents.

The survey was simultaneously conducted using an expanded 7-item version of the AMIQ containing two further questions scored using a 5-point Likert scale similar to that in the five-item AMIQ. The additional questions were: ‘If I were a landlord I would probably rent an apartment to [X]’ and ‘If I were an employer, I would interview [X] for a job’ (maximum score range –14 to +14). There was close correlation between scores with the AMIQ-5 and the scores for two additional items in the AMIQ-7 (simple linear correlation coefficient r=0.96; Spearman's rank correlation coefficient ρ =0.96); the AMIQ-7 did not reveal any additional information. There was no difference in the overall results and conclusions.

Discussion

Mechanisms of change and practical significance

A large and statistically significant difference in stigmatised attitudes was observed when hypothetical patients were presented positively compared with baseline descriptions of patients with active symptoms. This was observed with hypothetical patients with schizophrenia. The effect was significantly larger with substance misuse disorders. It could be argued that selectively presenting ‘success’ stories of patients who have recovered is simply ‘spin’ and would not generalise to other patients nor change the general experience of those with mental illness. However, a major difficulty with rehabilitation in mental disorder, including those with substance misuse disorders, is to convince members of the community such as employers or landlords that people can and do recover from mental illness. Our study convincingly demonstrates that the public have a much more positive attitude towards people who recover from addictive disorders than towards patients in relapse. Hence, it is worthwhile disseminating examples of successfully recovered patients. Presenting patients in a positive way can achieve a less stigmatised response to them.

Fig. 1. Forrest plot of Attitude to Mental Illness Questionnaire 5-item stigma scores for Table 1 . Scores are shown for attitudes towards people with opiate dependence, alcoholism and schizophrenia respectively for the control group (upper three boxes) and experimental group (lower three boxes).

The typical scores observed in the experimental group (0 to +1) remained significantly less than maximum scores in the original validation study for non-stigmatised groups such as people with diabetes or practising Christians. Participants scored hypothetical members of these groups around +5 (the range was –10 to +10 for the AMIQ). There seems to be a ‘glass ceiling’ around +1 on AMIQ scale scores which it is difficult for even people fully recovered from mental illness to exceed.

The maximum scores were similar in the experimental group for people in recovery from schizophrenia and substance misuse disorders (mean 0 to +1). However, the baseline scores in the control and follow-up studies were significantly different. An improvement of approximately 4 units was observed in respect to substance misuse disorder but only 2 units in respect to schizophrenia. One explanation for this is that the public regards substance misuse disorders as self-inflicted. The survey by Crisp et al (Reference Crisp, Gelder and Goddard2005) showed that three out of five people thought that people with alcoholism and drug addiction were to blame for their condition - an opinion endorsed by only 6% in relation to schizophrenia. Paradoxically, it is also possible that the public are prepared to give credit to people with substance misuse disorders who have engaged successfully in treatment or have overcome their addiction. In other words, the public may be prepared to reward or forgive the ‘recovering alcoholic’ and the ‘recovering heroin addict’, as in the biblical verse, ‘There will be more rejoicing in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who do not need to repent’ (Luke 15:7). Unfortunately, no similar effect appears to exist towards those with schizophrenia, who are presumably not held responsible for their condition and therefore not given credit for recovering from illness.

The psychology of repentance and forgiveness has been studied systematically over the past decade (Reference GullifordGulliford, 2004; McCullough et al, 2007). The verb ‘forgive’ can be defined as ‘to pardon, to cease to feel resentment or to forgo vengeance’, whereas to ‘repent’ may be defined as ‘to feel regret, remorse or to turn from sin’. People often seek to overcome social conflict and aggression by peacemaking and forgiveness. Three conditions have been suggested that motivate forgiveness: careworthiness, expected value and safety. Transgressors are careworthy when the victim perceives them as an appropriate target for moral concern - particularly if the transgressions are seen as unintentional or unavoidable. Transgressors have expected value when a victim anticipates that a future relationship may need to be developed. Transgressors are seen as safe when they seem unwilling or unable to harm their victim again. In relation to substance misuse, people are more willing to forgive people with whom they feel empathy (especially people who are perceived as unwell). Although most people are unlikely to seek a direct relationship with a recovering ‘addict’, they are likely to realise that recovery from addiction will reduce the damage former drug misusers inflict on society (whether by crime or by failure to fulfil obligations to their dependents). Feelings of safety and trust are enhanced when perpetrators express sincere remorse, apology, restitution and repentance. This makes the transgressor seem worthy of care, valuable and safe. Transgressors’ expressions of sympathy for their victims and desire to uphold social rules also enhance the prospect of forgiveness. Moreover, restitution is enhanced if individuals appear to be making a significant effort to overcome their faults or compensate victims for their transgressions. Some personality traits such as agreeableness, narcissism and religiosity also correlate with the propensity of people to forgive. Formal trials have shown that forgiveness for offenders can be enhanced by psychological interventions such as re-framing, social support and peer pressure (for example, in restorative justice conferences).

The results indicate that it is eminently worthwhile promoting positive images of people with substance misuse disorders in recovery. However, it is more difficult to produce a significant shift in stigmatised attitudes towards people with schizophrenia.

Attitudes to Mental Illness Questionnaire

Adapted from Cunningham et al (Reference Cunningham, Sobell and Chow1993) and validated in a previous study (Reference Luty, Fakuda and UmohLuty et al, 2006), the AMIQ is user-friendly. Test-retest reliability at 2-4 weeks was 0.702 (Pearson's correlation coefficient; n=256). Construct validity (Cronbach's alpha) was 0.933 (n=879). Alternate test reliability compared with Corrigan's Attributions Questionnaire was 0.704 (Spearman's rho=102; Reference Corrigan, Markowitz and WatsonCorrigan et al, 2003). Other available instruments are much longer, involve interviews or address the experience of stigma by those with mental illness, e.g. the Internalised Stigma of Mental Illness scale (Reference Ritsher, Otilingam and GrajalesRitsher et al, 2003; Reference Pinfold, Toulmin and ThornicroftPinfold et al, 2003) and Corrigan's Attribution Questionnaire (Reference Crisp, Gelder and RixCrisp et al, 2000; Reference Corrigan, Markowitz and WatsonCorrigan et al, 2003).

Other methods to reduce stigma

Action on Mental Health - A Guide to Promoting Social Inclusion (Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, 2004) provides 12 individual factsheets to reduce stigma. This supplements the efforts of the ‘Changing Minds’ campaign. Both give practical advice to health agencies, employers and stakeholders to tackle stigma. Providing factual information in brief factsheets (Penn et al,Reference Penn, Guynan and Daily1994, Reference Penn, Kommana and Mansfield1999; Reference Thornton and WahlThornton & Wahl, 1996) or through extensive interventions such as educational courses is reported to reduce stigma (Reference Mayville and PennMayville & Penn, 1998; Reference Penn and MartinPenn & Martin, 1998; Reference Corrigan and PennCorrigan & Penn, 1999). Unfortunately, responses tend to be small, especially if negative consequences of mental illness are also disseminated. Knox et al (Reference Knox, Smith and Hereby2003) showed that addressing stigmatised attitudes to mental illness among 4 million members of the US armed forces with mandatory training to recognise and treat mental illness significantly reduced suicide rates but not stigmatised attitudes; moreover, it was possible in this setting to insist on engagement in anti-stigma training, whereas involvement of the general public is entirely voluntary.

Wolff et al (Reference Wolff, Pathare and Craig1996) reported a labour-intensive controlled study of the effect of a public education campaign on community attitudes towards people with mental illness. It produced effects sizes of 1.23 for fear and exclusion, 1.22 for social control and 0.66 for goodwill. However, two earlier studies - one in Canada (Reference Cummings and CummingsCummings & Cummings, 1957) and one in Northamptonshire (Reference Gatherer and ReidGatherer & Reid, 1963) - produced ineffective results. Pinfold et al (Reference Pinfold, Toulmin and Thornicroft2003) reported a project in which 472 English secondary school children attended mental health awareness workshops. Overall, there was a small but positive shift in their understanding of mental illness. Penn et al (Reference Penn, Chamberlin and Mueser2003) reported a study of 163 US undergraduates who were assigned randomly to four groups: three watched a documentary - about schizophrenia (represented realistically), polar bears or being overweight - and the fourth was a ‘no video’ control group. The schizophrenia documentary did not change attitudes. Depicting the negative consequences of schizophrenia may be realistic but may not be the best way to reduce stigma. Depicting a success story may be more effective, although viewers may then classify this as an exception to the rule (Reference Corrigan and PennCorrigan & Penn, 1999). Marketing strategies for commercial products invariably associate the product with positive images (Reference Atkinson, Atkinson and SmithAtkinson et al, 1996) and avoid associating it with any negative images (Reference Wilmshurst and MackayWilmshurst & Mackay, 2002). In our study we confirmed that the most effective technique to reduce stigma was to associate a person who is mentally ill with a picture of an attractive man wearing a suit to suggest that he was in professional employment. We attempted to challenge the stereotype that ‘addicts’ and people with mental illness are physically undesirable, unkempt and unemployed.

Promoting direct interpersonal contact with people who are mentally ill may be an effective strategy, but the amount of contact required remains unknown (Reference Penn, Guynan and DailyPenn et al, 1994; Reference Wolff, Pathare and CraigWolff et al, 1996; Reference Corrigan and PennCorrigan & Penn, 1999; Reference Pinfold, Toulmin and ThornicroftPinfold et al, 2003). It would be difficult, in practice, to ensure that a significant proportion of the public had contact with people with a severe mental illness. Crisp et al (Reference Crisp, Gelder and Goddard2005) noted that the positive effect of contact with people with a single form of mental disorder such as schizophrenia does not generalise to other mental disorders such as alcoholism. Despite the fact that alcohol problems are several times more common in Britain than opiate dependence (Reference Farrell, Howes and BebbingtonFarrell et al, 2001), our results showed no difference in the attitude of participants to people with alcoholism and those with opiate dependence. This argues against the anti-stigmatising effect of direct contact with people with certain mental illnesses.

Mass media methods may be more cost-effective, can educate about most forms of mental illness, can reach a wider audience and must therefore be developed.

Strengths and limitations

The survey involved follow-up of participants recruited for a previous trial. Although there was an excess of female respondents, age and employment status of participants were reasonably matched to that from UK census surveys. Although the sample appears to be a reasonable cross-section of the British public, it is to an extent self-selecting and may not generalise across the whole population. Ideally, interviews could be conducted using a quota survey of households with repeat visits for non-responders (Reference Crisp, Gelder and RixCrisp et al, 2000). Unfortunately this is prohibitively expensive.

The study presented a hypothetical person who was mentally ill. This is less accurate than real experience - it was not possible to measure stigmatised behaviour towards real people who are mentally ill. Moreover, the written views and expressed attitudes may not translate into any enduring behavioural change. Social desirability bias may also affect the results. However, the results indicated a very negative view of people with active substance misuse disorder and suggest that participants had little reservation about indicating their disapproval of these conditions. There was no direct contact between participants and researchers, but participants are likely to make some assumptions about the potentially liberal beliefs of researchers into mental health. This would indicate that social disability bias had a small effect.

Appendix 1

Attitudes to Mental Illness Questionnaire (AMIQ)

Please read the following statement: ‘John has been injecting heroin daily for 1 year’. Please underline the answer that best reflects your views:

-

1. Do you think that this would damage John's career?

Strongly agree–2 / Agree–1 / Neutral0 / Disagree+1 / Strongly disagree+2 / Don't know0

-

2. I would be comfortable if John was my colleague at work?

Strongly agree+2 / Agree+1 / Neutral0 / Disagree–1 / Strongly disagree–2 / Don't know0

-

3. I would be comfortable about inviting John to a dinner party?

Strongly agree+2 / Agree+1 / Neutral0 / Disagree–1 / Strongly disagree–2 / Don't know0

-

4. How likely do you think it would be for John's wife to leave him?

Very likely–2 / Quite likely–1 / Neutral0 / Unlikely+1 / Very unlikely+2 / Don't know0

-

5. How likely do you think it would be for John to get in trouble with the law?

Very likely–2 / Quite likely–1 / Neutral0 / Unlikely+1 / Very unlikely+2 / Don't know0

Appendix 2

Control (negative) vignettes (no photograph)

‘John was injecting heroin daily for 1 year.’

‘Michael has schizophrenia. He needs an injection of medication every 2 weeks. He was detained in hospital for several weeks 2 years ago because he was hearing voices from the Devil and thought that he had the power to cause earthquakes.’

‘Steve has been drinking heavily for 5 years. He usually drinks more than half a bottle of spirits each day.’

Positive vignettes (with photographs)

‘Chris was injecting heroin daily for 1 year. He is now in treatment and he is not using heroin or any other illegal drugs. He is working full-time.’

‘John needs an injection of medication every 2 weeks. 2 years ago he was hearing voices from the Devil and thought that he had the power to cause earthquakes. He is now recovered and is back at work.’

‘Francis has been drinking heavily for 5 years. He is going for treatment and has started attending Alcoholics Anonymous. He has stopped drinking.’

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by British Academy grant SG-35479.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.