Summations

∙ This review summarises the main facts of the history of antidepressant drug research and how ketamine revolutionized the search for new antidepressants.

∙ The reviewed evidence shows the main problems in the development of antidepressant drugs and the stagnation of the development of these drugs at the end of the 20th century.

∙ The main evidence of the antidepressant effects of ketamine, the new biological targets that ketamine helped identify and the drugs that were developed based on ketamine’s mechanism of action are presented to show ketamine’s relevance in the field.

Considerations

∙ The review is based on the most relevant publications regarding the history of antidepressant drugs and on the relevant data demonstrating the antidepressant effects of ketamine.

∙ This review does not aim to include all literature regarding the behavioural effects of ketamine or N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) antagonists. All articles were selected based on their relevance to the field of antidepressant research.

Introduction

Major depression is a serious and debilitating disorder that can ultimately lead to suicide (Reference Organization1,Reference Millan2). The number of individuals affected by depression increased by 18.4% from 2005 to 2015, and more than 300 million individuals are estimated to suffer from depression at present (Reference Organization1). Furthermore, the World Health Organization indicates that depression is the leading cause of disability (Reference Organization1). Therefore, it is evident that appropriate and effective treatments for this disorder are necessary.

The pharmacological treatment for major depression is mostly based on drugs targeting the monoaminergic system (Reference Millan2,Reference Hindmarch3). When they were developed, these drugs initiated a significant evolution for the treatment of mood disorders; but as depression becomes a growing health problem, these drugs do not follow the same pace regarding efficacy and acceptance (Reference Millan2,Reference Hindmarch3). Consequently, the need and pressure for the development of new antidepressant drugs with improved efficacy is increasing.

The most promising solution for this challenge emerged at the beginning of the 21st century, when the fast and long-lasting antidepressant effects of the glutamatergic agent, ketamine, were shown for the first time (Reference Berman, Cappiello and Anand4). A great body of evidence has been built, showing the potential of glutamatergic drugs, like ketamine, as new and more effective antidepressant drugs (Reference Abdallah, Adams, Kelmendi, Esterlis, Sanacora and Krystal5–Reference Browne and Lucki7).

Thus, in the present paper, we will review the history of the development of antidepressant drugs to show how and why monoaminergic antidepressants do not fulfil their treatment objectives. Furthermore, we will discuss how ketamine made history in the development of antidepressants, and how it is significantly improving this field. In order to do so, we review the main aspects of ketamine’s mechanism of action and the drugs developed based on such a mechanism.

The development of classical antidepressant drugs

The dawn of modern psychopharmacology and the first antidepressants

Until the late 1930s, there were no really effective treatments for depressive disorders. Many attempts were made, but they were almost all complete failures. For example, some clinicians found partial relief of symptoms such as distress and agitation in depressive patients by using tinctura opii, first prescribed by Emil Kraepelin at the end of 19th century. Unfortunately, this had no effect on the depressed mood per se or suicidal tendencies (Reference Ban8,Reference Lehmann9). However, in the 1930s, the first treatments for catatonia, a type of schizophrenia, were discovered (Reference Lehmann and Ban10). These findings and the discovery that the experimental administration of psychogenic agents could induce catatonia (Reference Ban8) were a landmark for the emerging of biological psychiatry.

In parallel to these discoveries, Ernest Forneau and Daniel Bovet studied the structure of histamine aiming to find an antagonist since it had been confirmed that histamine was the causative agent in allergic response; in 1937, the first antihistaminic was synthesised (Reference Cozanitis11). During the following years, several researchers worked to synthesise and study the link between the structure and activity of several antihistamines. Around 1950, this relationship was well established and contributed to the discovery of almost all antidepressants and antipsychotics (Reference Domino12) [for more structure-related information, see Domino (Reference Domino12)].

Shortly after World War II, P. Charpentier and his colleagues at Rhône Poulenc in France synthesised and tested a series of phenothiazine amines, which pharmacologists D. Bovet, B. Halpern and R. Ducrot found to have significant and long-lasting antihistaminic properties (Reference Domino12). One of the most potent phenothiazine amines was promethazine. The therapeutic and commercial success of promethazine as a sedative and possible antipsychotic prompted the synthesis of many modified phenothiazines for their potential central nervous system (CNS) effects (Reference Domino12). Finally, the first antipsychotic, chlorpromazine, was synthesised when chlorine was added to the promethazine structure (Reference Domino12), forming the basis of the development of the first antidepressants.

The therapeutic and commercial success of N-aminoalkylphenothiazines such as promethazine, promazine and chlorpromazine, motivated an enormous effort in the molecular modification of the polycyclic phenothiazine ring structure and its N-aminoalkyl side chain (Reference Domino12). In 1945, Häfliger and Schinder, replaced the Sulphur bridge of the phenothiazine ring of promethazine with an ethylene bridge to synthesise G22355, a weak antihistamine and mild anticholinergic with sedative properties, in normal human volunteers (Reference Domino12). Since the chemical structure was similar to the one of chlorpromazine, it was given to Roland Kuhn in Germany to test its antipsychotic properties. The substance was ineffective in schizophrenia, but Kuhn recognised some of its potential antidepressant properties (Reference Kuhn13,Reference Ayd and Blackwell14). During the World Psychiatric Association Meeting in Zurich, in 1957, the first public report on the antidepressant effects of G22355, later named imipramine, was written by Kuhn (Reference Lehmann9). Kuhn discovered that among patients with different psychiatric disorders treated with imipramine, those with endogenous depression and mental and motor retardation showed a remarkable improvement after ~1 to 6 weeks of daily therapy (Reference Domino12). Thus, the first clinically useful tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) was discovered, and by the end of the same year of its first publication, it was released for clinical use in Switzerland under the brand name Tofranil (Reference Domino12,Reference Ban15).

Parallel to the study of imipramine, the history of iproniazid started at the Sea View Hospital on Staten Island (New York). In 1952, Irving J. Selikoff and Edward Robitzek carried out studies on the clinical effects of iproniazid. They observed that this drug greatly stimulated the CNS, which was initially interpreted as a side effect. At that time, many studies on the antidepressant effects of antitubercular hydrazide agents were performed (Reference Zeller, Barsky, Fouts, Kirchheimer and Vanorden16,Reference Lopez-Munoz and Alamo17). It was during one of these studies that the term ‘antidepressant’ was probably coined by Max Lurie, a psychiatrist with a private practice in Cincinnati, to refer to the effect of isoniazid in depressed patients (Reference Salzer and Lurie18).

In 1957, psychiatrists Nathan S. Kline, Harry P. Loomer and John C. Saunders from Rockland State Hospital (Orangeburg, NY) were the first to present results assessing the efficacy of iproniazid in non-tuberculosis depressed patients (Reference Lehmann9,Reference Lopez-Munoz and Alamo17). Just 1 year after this first presentation at the Syracuse meeting (April, 1957), more than 400 000 patients affected by depression had been treated with the first class of antidepressants to reach the market (Reference Lewis19).

This a new set of drugs was defined and called antidepressants, which were pioneered by iproniazid [later classified as a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI)] and imipramine (later classified as a TCA).

The rise and reign of Prozac

The discovery of the mechanisms of action of iproniazid and imipramine was of fundamental importance to the formulation of the initial aetiological theories of depressive disorder.

By the time the antidepressant effects of iproniazid we published, it was already known that it inhibited the enzyme monoamine oxidase (MAO). In 1952, the team led by Ernst Albert Zeller at Northwestern University Medical School (Chicago, IL) observed for the first time that iproniazid (and not isoniazid) was capable of inhibiting MAO (Reference Lopez-Munoz, Alamo, Juckel and Assion20). In 1959, Sigg observed the potentiation of noradrenaline (NA) by imipramine (Reference Sigg21), and, in 1961, Brodie and his team at the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) introduced the reserpine syndrome as a model for depression. At the same time, Axelrod and his co-workers at NIMH discovered the reuptake blocking of noradrenaline by TCAs (Reference Herting, Axelrod and Whitby22). Finally, in 1965, Schildkraut, Bunney and Davis suggested the catecholamine hypothesis of depression, postulating that depression was be caused by low levels of epinephrine and norepinephrine in the CNS (Reference Schildkraut23,Reference Schildkraut, Gordon and Durell24).

At the same time, other findings contributed to the introduction of a new protagonist, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT or serotonin) in the search for the molecule behind depression. In addition to the noradrenergic system (Reference Coppen25), reserpine, imipramine and iproniazid also affect the 5-HT system, and 5-HT neurotransmission seems to have an essential role in animal sedation (Reference Brodie, Comer, Costa and Dlabac26). Additionally, the therapeutic effect of MAOIs and TCAs was later shown to be blocked by the administration of 5-HT synthesis inhibitors (Reference Shopsin, Friedman and Gershon27,Reference Shopsin, Gershon, Goldstein, Friedman and Wilk28). Therefore, Coppen (1967) proposed that 5-HT was a more important neurotransmitter in depression than NA, based on experiments on animals in which the administration of tryptophan, the precursor of serotonin, boosted the antidepressant-like effects of MAOIs (Reference Lopez-Munoz and Alamo17,Reference Coppen25,Reference Coppen, Shaw and Farrell29). In 1969, the discovery that TCAs could block the reuptake of serotonin in presynaptic neurons allowed Lapin and Oxenkrug to postulate the serotonergic theory of depression, which was based on a deficit of serotonin at an inter-synaptic level in certain brain regions (Reference Lapin and Oxenkrug30).

Even though there was initially no consensus whether the antidepressant-like effects of iproniazid resulted from MAO inhibition or not, several other MAOIs were introduced on the market after 1957 (Reference Ban31). Despite being one of the only alternatives for treating depression, the hepatotoxicity caused by drugs such as iproniazid and pheniprazine and the hypertensive crisis induced by the inhibition of peripheral MAO caused this class of drugs to become obsolete (Reference Lopez-Munoz, Alamo, Juckel and Assion20). In 1961, other tricyclics such as amitriptyline were synthesised by modifying the structure of imipramine (Reference Kuhn32), and the desmethyl derivative of imipramine, desipramine, was introduced in 1964 as the active metabolite of imipramine (Reference Brodie, Bickel and Sulser33). In 1963, nortriptyline was approved in Great Britain, followed by trimipramine, protriptyline (1966), iprindole (1967), dothiepin and doxepin (1969) (Reference Fangmann, Assion, Juckel, Gonzalez and Lopez-Munoz34). Despite being less tolerated due to a higher probability of adverse effects than the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) that were to come later, TCAs are currently still among the most frequently prescribed drugs in the world (35,Reference Abbing-Karahagopian, Huerta and Souverein36).

For the first time in the history of psychopharmacology, the postulation of the monoaminergic theories of depression led to a new search methodology for new therapeutic drugs. Having fluoxetine as their prototype, the SSRIs were the first class of drugs developed after a planned strategy and with a methodology of rational design, aiming for drugs which act in a specific site (the protein responsible for the serotonin reuptake, 5-HT). This strategy made it possible to avoid unspecific actions and culminated in more selective drugs and, consequently, decreased the frequency and probability of undesired effects (Reference Lopez-Munoz and Alamo17).

At first, the fluoxetine idealisation was based on the prominent serotonin theory of depression which was in evidence in the 1960s, backed up by the literature at the time. Subsequently, the pharmaceutical company Eli Lily created a ‘serotonin-depression study team’, composed by the researchers Fuller, WongMolloy and Rathbun (Reference Lopez-Munoz and Alamo17) whose search for molecules that could selectively inhibit the reuptake of serotonin aimed to minimise collateral effects, such as cardiovascular toxicity and anticholinergic properties of the TCAs. Therefore, they started, once more, with basic antihistamines and synthesised dozens of compounds by modifying phenoxyphenylpropylamines (Reference Domino12). On July 24th, 1972, LY-110140 (fluoxetine hydrochloride) was designated the most powerful and selective inhibitor of serotonin uptake among all the compounds developed (Reference Wong, Horng, Bymaster, Hauser and Molloy37). In December 1987 after a series of clinical studies confirming that fluoxetine was as effective as the TCAs, along with the advantage of fewer adverse effects (Reference López-Muñoz and Álamo38,39), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved its clinical use, allowing Prozac to be released onto the market (Reference Lopez-Munoz and Alamo17).

Prozac had the fastest growth in use in the history of psychotropic drugs. By 1990, it was the most widely prescribed drug in North America and, in 1994, it was the second biggest selling drug in the world (Reference Lopez-Munoz and Alamo17). The increasing need for a drug to treat the fearsome medical condition: Major depression, which strongly stimulated the rise and establishment of fluoxetine and the subsequent SSRIs to unprecedented levels. In contrast, in 1982, the first SSRI, zimelidine, was marketed in Sweden but had to be withdrawn from the market due to serious adverse effects related to its use, namely Guillain-Barré Syndrome (Reference Fagius, Osterman, Siden and Wiholm40). However, four other SSRIs were released in the market alongside fluoxetine; that is, citalopram (Lundbeck, 1989 in Denmark), fluvoxamine (Solvay, 1983 in Switzerland), paroxetine (AS Ferrosan, Novo Nordisk, 1991 in Sweden) and sertraline (Pfizer, 1990 in UK) (Reference Lopez-Munoz and Alamo17).

The number of visits to general practitioners due to depression increased from 10.9 million in 1988 to 20.43 million in 1994 (Reference Pincus, Tanielian and Marcus41), and the prescriptions for all antidepressants rose from 40 million in 1988 to 120 million just one decade later (Reference Szegedy-Maszak42). Even though it is highly debatable whether the rise of Prozac was only a psychotherapeutic phenomenon or placebo features were involved, the fact is that it happened in such an unprecedented manner that it is referred to as the ‘Prozac Boom’ (Reference Slingsby43).

The dusk of antidepressants in the late 20th century

Even though SSRIs dominated the antidepressant market in the 1990s, not all expectations about these drugs were fulfilled. Although the adverse effects of the TCAs were worse, the SSRIs still caused side effects; for example, fluoxetine and SSRIs can interfere with sex and appetite, cause vomiting and nausea, irritability, anxiety, insomnia and headaches (Reference Millan2). To a lesser extent, it can also induce parkinsonism, agitation, spasms and tics (Reference Millan2).

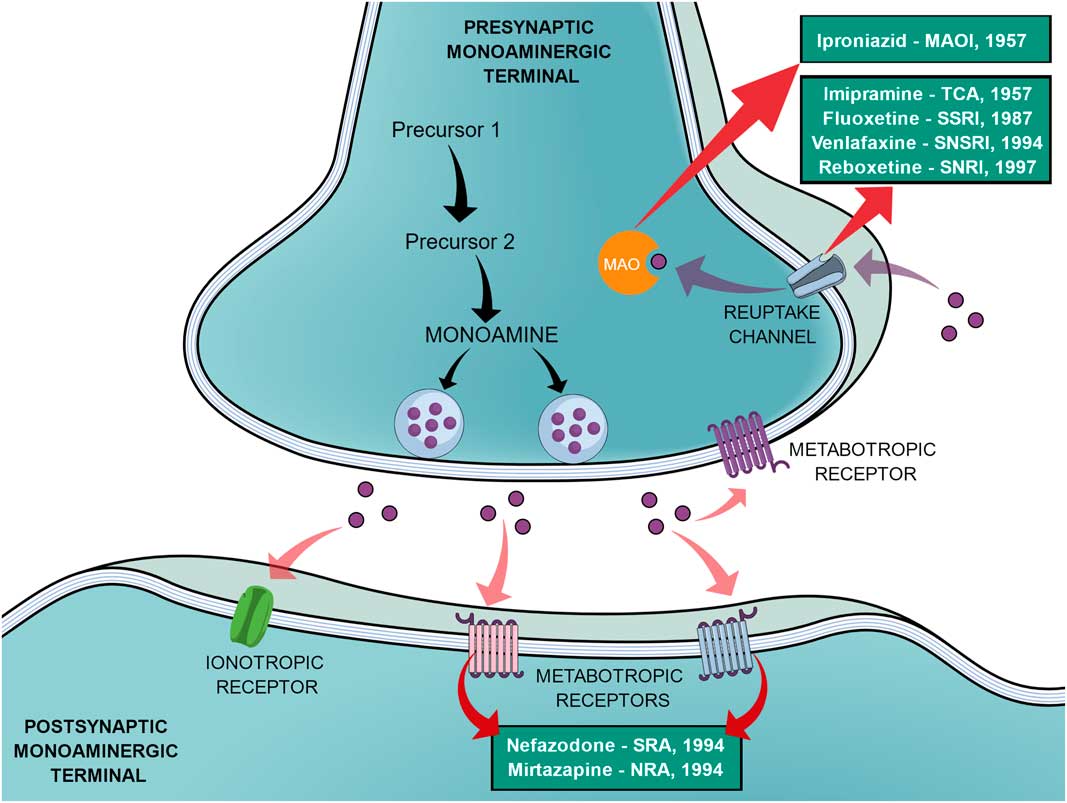

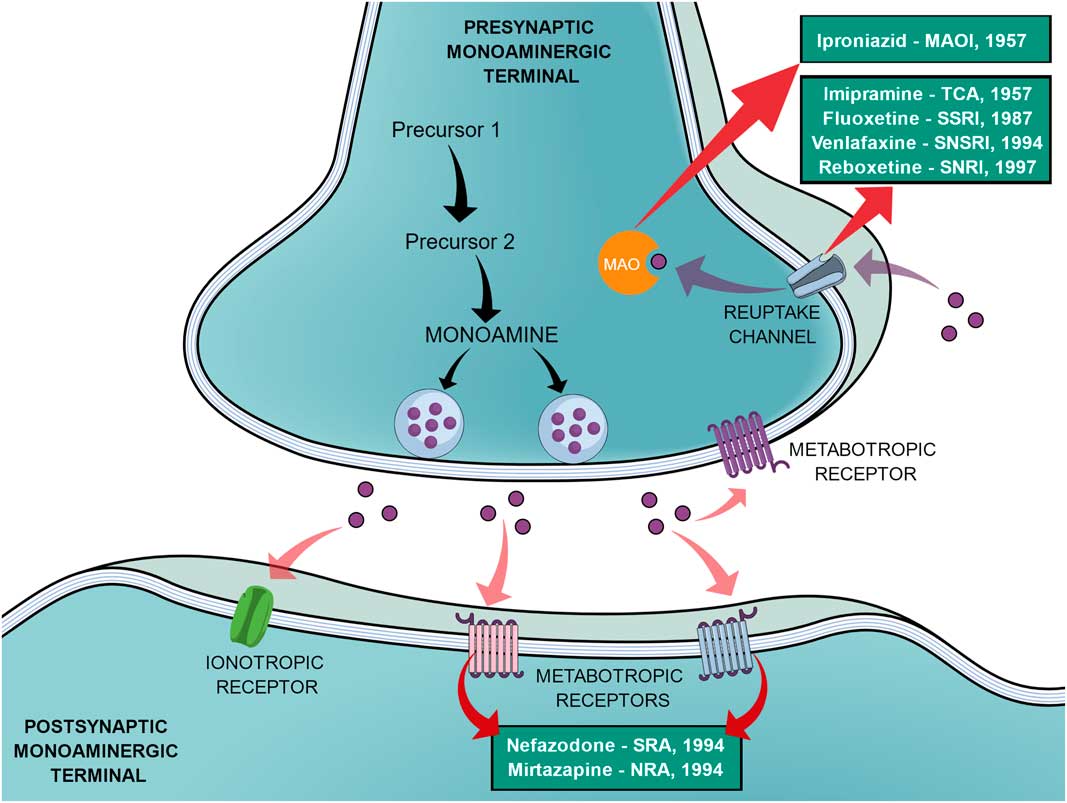

In an effort to reduce the adverse effects of the first SSRIs, other antidepressants emerged during the 1990s, such as venlafaxine (a selective noradrenaline and serotonin reuptake inhibitor), reboxetine (a selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor), nefazodone (selective serotonin-5HT2A receptor blocker, a weak 5-HT reuptake inhibitor, structurally and pharmacologically related to trazodone) and mirtazapine (α2-adrenoreceptor blocker, pharmacologically related to mianserin) (Reference Millan2,Reference Ban31). In the same way as the SSRIs, these new agents elicited different tolerance rates and side effects but offered no improvement in efficacy, therefore not being a huge advancement (Reference Millan2). Figure 1 shows a generic representation of a monoaminergic neurotransmission with the main targets of classical antidepressants and the year that the main antidepressant drugs reached the market.

Fig. 1 General representation of a monoaminergic neurotransmission. Black arrows show the general synthesis process of monoamines until they are stored into the vesicles. Purple dots represent the monoamines. Pink arrows show the main neuronal targets of monoamines, which can be postsynaptic ionotropic and metabotropic receptors, as they can also act on presynaptic metabotropic receptors. Purple arrows show the reuptake mechanism of monoamines that leads them to be degraded by monoamine oxidase (MAO). Red arrows show the main targets of the classical monoaminergic antidepressants. Green boxes show the main drugs and classes of antidepressants related to each target and the year that each drug reached the market.

The SSRIs have not succeeded in solving several of the previous issues related to the use of antidepressants. For example, it still takes from 2 to 4 weeks for these drugs to exert an antidepressant effect (Reference Hindmarch3). This delay of clinical effect has always raised questions about the veracity of the monoaminergic hypothesis of depression, since studies show an acute increase in monoamines in the synaptic cleft (noradrenaline or serotonin) right after the treatment (Reference Nestler44). In addition, the decrease of serotonin levels in the brain caused by the acute depletion of tryptophan, serotonin’s precursor, does not induce a depressive-like behaviour in healthy humans (Reference Booij, Van der Does and Riedel45–Reference Moreno, Parkinson and Palmer47). This evidence shows that much more than monoaminergic neurotransmitter levels should be targeted in the brain of depressed individuals.

In 1937, Hohman published an article with a retrospective study of the outcome of depressed patients. After 7 years of observation, only one in three recovered within a year, whereas one out of four recovered within 2 years, and about 15% remained chronic and did not recover at all (Reference Hohman48). At that time, however, no effective treatments for depression existed. Even nowadays, studies on the remission rates of depression after treatment show conflicting numbers. According to some authors, this number ranges from 30% (Reference Al-Harbi49) to 45% of the patients (Reference Keks, Burrows and Copolov50), whereas the literature comprises many different assumptions. One of the reasons for these differences stems from divergences in the samples analysed; but in general, a significant percentage of these patients never achieve full remission.

Some authors believed that the treatments available on the market only reduced the frequency, duration and severity of symptoms as well as the mortality by suicide (Reference Lehmann9). In fact, in the last decade, the non-effectiveness of antidepressants has been subject of considerable debate. However, the World Health Organization’s compiled data show that both TCAs and SSRIs are significantly more effective than placebo (51).

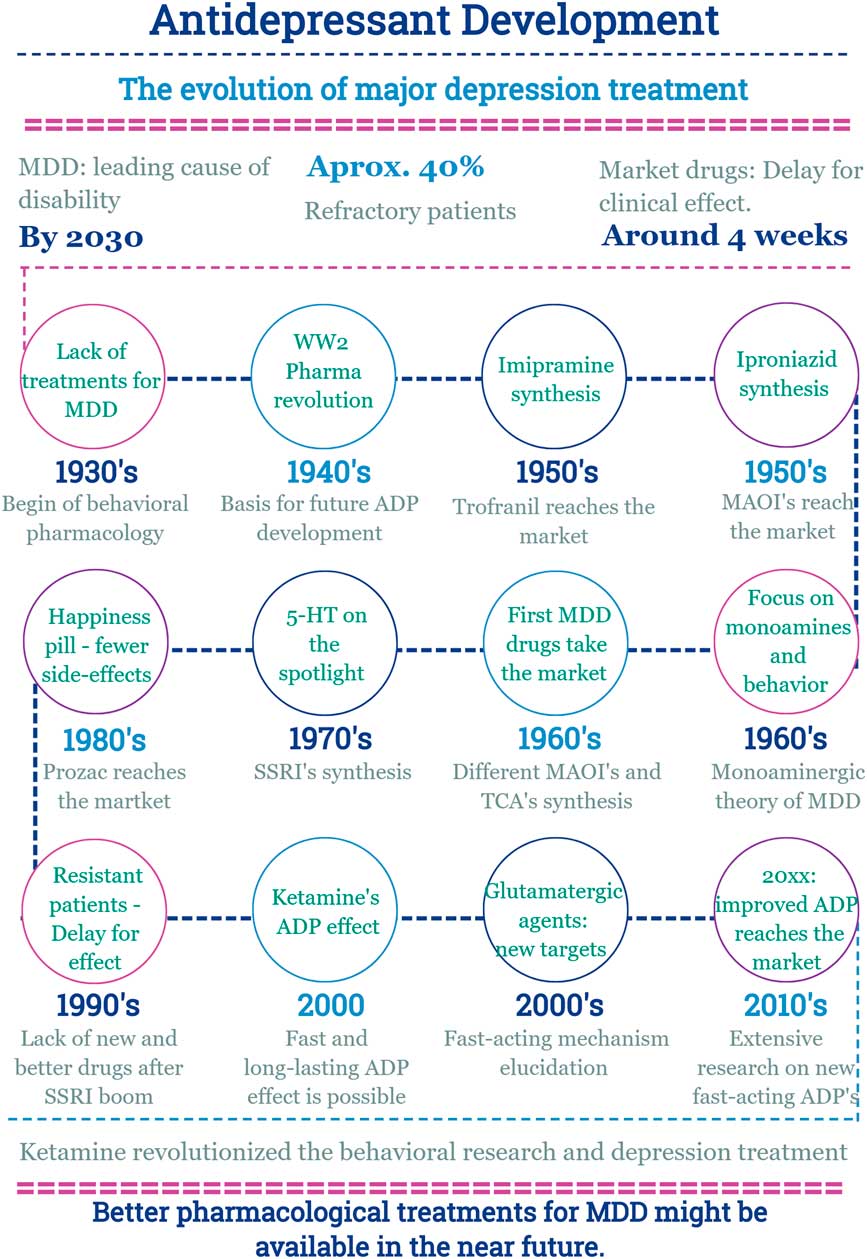

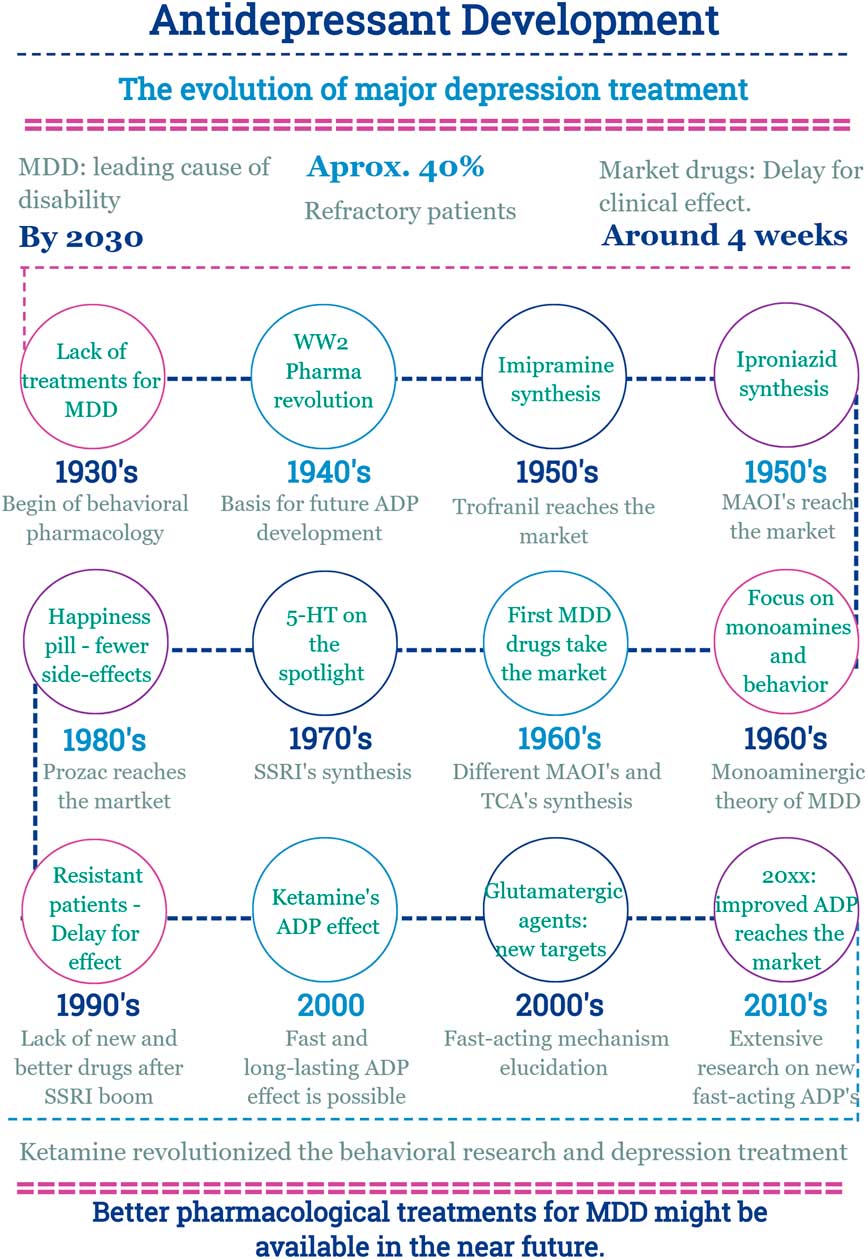

In this scenario, the discovery of a new effect of an old drug emerges (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Main facts on antidepressant drug development from 1930 until now. ADP, antidepressant; MDD, major depressive disorder; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitors; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressants; WW2, World War 2.

Ketamine: turning tables on antidepressant research

The history of ketamine

In 1956, an anaesthetic compound called phencyclidine was synthesised at Parke, Davis & Co. laboratories in Detroit, MI, USA (Reference Maddox, Godefroi and Parcell52). Animal studies showed that this drug had remarkable anaesthetic effects and could cause behavioural alterations. Thus, after toxicity studies, it was approved for use in humans (Reference Domino53). However, clinical studies showed that phencyclidine was not ideal for human anaesthesia since it might cause long-lasting emergence delirium and lead to something similar to a schizophrenic syndrome (Reference Aniline and Pitts54). Given that this drug had interesting anaesthetic effects, Parke, Davis & Co. decided to search for a phencyclidine derivate with a shorter period of action to avoid the long-lasting behavioural side effects (Reference Domino53). One of the synthesised compounds, CI-581, successfully underwent pre-clinical studies and was approved for human studies, which led to Parke, Davis & Co. contacting Dr. Edward F. Domino to lead such clinical studies. In 1964, the first human experiment with CI-581, later named as ketamine, was conducted on prisoners from the Jackson Prison, Michigan, USA. The studies conducted by Dr. Domino produced notable results accompanied by fewer side effects (Reference Domino53). However, the behavioural side effects of ketamine were still considerable and in order to get the FDA approval for clinical use, they decided to call it a ‘dissociative anaesthetic’, which proved to be a successful measure. Interestingly, the term ‘dissociative anaesthetic’ came from Dr. Domino’s wife during a conversation as described, among other facts about ketamine development, in his insightful review (Reference Domino53).

The history of ketamine up to now can be divided into five different periods according to the number of published articles after its synthesis and the different phases in the studies on its effects. In the first published clinical study on ketamine from 1965, Edward F. Domino et al. describe the clinical effects of a dissociative anaesthetic called CI-581 (Reference Domino, Chodoff and Corssen55). From 1965 to the end of 1969, fewer than 50 published studies corroborate the potential effects of ketamine as an anaesthetic agent for clinical use (Reference Gjessing56,Reference Corssen, Domino and Bree57).

During the second period from 1970 to the end of 1974, the use of ketamine in different kinds of anaesthesia as well as its dissociative effects are confirmed and established (Reference Dundee, Bovill, Clarke and Pandit58–Reference Sussman60). This period represents the beginning of extensive research and interest in ketamine, substantiated by more than 1000 studies published during these 5 years. The first and second period also mark the transition of ketamine from a street abuse drug to a scheduled and controlled drug after its approval by the FDA (Reference Domino53). The fact that is it still used as an abuse drug represents a main concern in using ketamine as an antidepressant agent (Reference Corazza, Assi and Schifano61,Reference Sanacora and Schatzberg62).

During the third period from 1975 to 1989, 300–400 articles were produced a year, depicting the mechanisms of ketamine and its effects. In parallel, the glutamatergic system was also being characterised at the time, and the NMDA receptor was identified as one of the receptors of this neurotransmission system (Reference Collingridge and Watkins63). Thus, the main site of action of ketamine was described, since ketamine blocks the effects of the glutamatergic mediator glutamate on the NMDA receptor (NMDAR) by physically blocking the receptor channel (Reference Anis, Berry, Burton and Lodge64,Reference Harrison and Simmonds65). However, it is important to highlight that ketamine is not selective only to the NMDAR; to a lesser extent, it can also on over other targets such as opioid receptors, sigma receptors and by inhibiting the reuptake of monoamines (Reference Persson66–Reference du Jardin, Muller, Elfving, Dale, Wegener and Sanchez68).

During the fourth period, dating from 1990 to 1999, around 470–600 published articles related to ketamine were produced a year. The interest in the glutamatergic system and its importance in the control of behavioural responses to stress exposition was also growing. Consequently, ketamine was under the spotlight since its main target was now known. In 1990, studies showed that the injection of NMDA modulators, like MK-801 and ACPC, was capable of inducing antidepressant-like effects in mice exposed to the forced swim test (Reference Trullas and Skolnick69). A few years later, further evidence showed that stress exposition would increase glutamate release in key areas for behaviour control in the brain as elucidated by Moghaddam et al. in different works (Reference Moghaddam70–Reference Moghaddam72). Corroborating such findings, Nowak et al. and Skolnick et al. demonstrated that treatment with classical monoaminergic antidepressant drugs induced adaptive changes on NMDARs and in brain areas important to mood control (Reference Nowak, Trullas, Layer, Skolnick and Paul73,Reference Skolnick, Layer, Popik, Nowak, Paul and Trullas74). Therefore, it was during the final decade of the 20th century that researchers laid the foundations for the realisation of the involvement of glutamatergic mechanism in the neurobiology of depression.

Finally, the fifth period comprised an explosion of interest and research in ketamine and its behavioural effects. In the beginning of 2000, Biological Psychiatry published a groundbreaking study by Berman RM et al. who for the first time showed that it was possible to obtain fast and lasting antidepressant effects; that is, within hours and up to 3 days (Reference Berman, Cappiello and Anand4). Moreover, such effects could be obtained with a reduced dose of an already widely used drug: Ketamine (Reference Berman, Cappiello and Anand4). This came at a time of intense pressure for the development of antidepressants, since depression was affecting an increasing number of individuals and no better treatment options had been discovered. The year 2000 marked the shift conducted by ketamine in the history of the development of antidepressant drugs, since a new treatment to the ‘plague of the 21st Century’, that is major depression, was found.

Old drug, new insights on depression research

It took more than 40 years from the initial synthesis of ketamine until its antidepressant effects were elucidated by Berman et al. in 2000. These effects were corroborated by several other clinical and pre-clinical studies (Reference Browne and Lucki7,Reference Krystal, Sanacora and Duman75,Reference Abdallah, Sanacora, Duman and Krystal76). The trials executed by Dr. Carlos Zarate Junior’s research group are the major clinical evidence supporting how ketamine elicits fast and long-lasting effects, as well as they support the mechanisms through which it can be effective in treatment-resistant depression (Reference Zarate, Singh and Carlson77–Reference Zarate, Brutsche and Ibrahim79). In a great variety of animal models, several pre-clinical studies have shown that ketamine and other glutamatergic modulators can promote antidepressant-like effects as they also help to identify the mechanisms through which such drugs induce their behavioural effects (Reference Li, Lee and Liu80–Reference Pereira, Romano, Wegener and Joca83). A quick search in the online database clinicaltrials.gov (last consulted on 21/09/2017) shows more than 100 clinical trials involving ketamine and major depression exist; 44 of studies are recruiting or active, thus reinforcing the impact of ketamine on antidepressant research.

Depicting the mechanism of ketamine: more than NMDA antagonism

The mechanism responsible for ketamine’s antidepressant effects goes beyond the antagonism of glutamate on the NMDAR. It involves a multistep and complex cascade of events relying on different molecular targets. We will now review the main mediators and the most important evidence supporting the proposed mechanism of action of ketamine as an antidepressant.

The antidepressant mechanism of action of ketamine

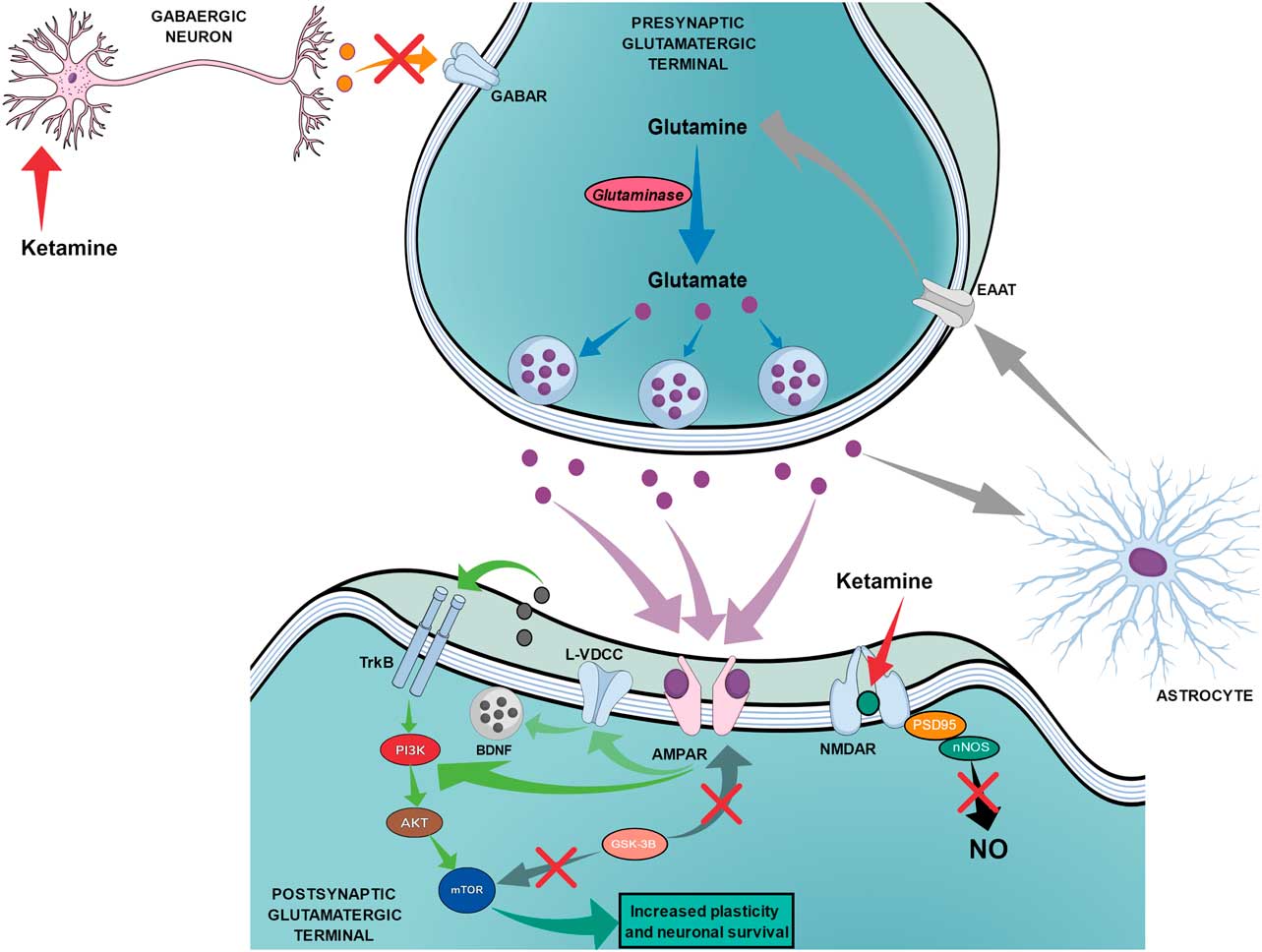

The proposed mechanism of action for ketamine can be divided into two chains of events. The first chain starts with the antagonism of the NMDAR, which is subsequently followed by three main steps: the reduction of nitric oxide (NO) production, the increase of glutamate release and the increased activation of AMPA receptors (AMPAR). Figure 3 shows the proposed mechanism of action of ketamine that leads to fast and long-lasting antidepressant effects.

Fig. 3 The proposed mechanism of action of ketamine regarding fast and long-lasting antidepressant effects. Red arrows show the beginning of ketamine’s action by blocking N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) on postsynaptic glutamatergic terminals and on gabaergic neurons, which leads to two main simultaneous effects. The black arrow shows that the blockade of NMDAR on postsynaptic glutamatergic terminals leads to reduced production of nitric oxide (NO). The orange arrow shows the reduced release of GABA by gabaergic neurons, which leads to reduced inhibition of presynaptic glutamatergic terminals and increased release of glutamate. The increased release of glutamate (purple dots) leads to an augmented drive of activation through AMPA receptors (AMPAR) as shown by purple arrows. Green arrows show that the activation of AMPAR can lead to (1) direct stimulation of the PI3K–AKT–mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway or (2) indirect activation of the same pathway through the activation of L-type voltage dependent calcium channels (L-VDCC), which increases the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) that can then activate tyrosine receptor kinase B (TrkB) receptors. Dark grey arrows show the reduction of the glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) effects over mTOR and AMPAR. Light grey arrows show the recycling of glutamate occurring through astrocytes, which release glutamine that will be transported to the presynaptic terminal by excitatory amino acid transporters (EAAT). Blue arrows show the synthesis of glutamate from glutamine through glutaminase action until the storage into the vesicles.

The production of NO can be induced by several neurotransmission systems like the cholinergic (Reference Felder84,Reference Alderton, Cooper and Knowles85), serotonergic (Reference Rahimian, Fakhfouri and Ejtemaei Mehr86) and purinergic systems (Reference Florenzano, Viscomi, Amadio, D’Ambrosi, Volonte and Molinari87,Reference Pereira, Casarotto, Hiroaki-Sato, Sartim, Guimaraes and Joca88). However, NMDAR activation is the main trigger for NO production (Reference Garthwaite, Garthwaite, Palmer and Moncada89). After NMDAR activation, an increase in calcium influx is observed, activating neuronal responses as it also leads to the formation of the Ca+2–calmodulin complex, which, in turn, activates neuronal NO synthase to produce NO (Reference Guix, Uribesalgo, Coma and Munoz90). NO is an atypical neurotransmitter that plays an important role in the neurobiology of depression (Reference Joca, Moreira and Wegener91). Various reports show that NO can modulate different processes in the brain as it is capable of modulating the release of neurotransmitters and affect neuronal plasticity (Reference Guix, Uribesalgo, Coma and Munoz90,Reference Calabrese, Mancuso, Calvani, Rizzarelli, Butterfield and Stella92). Many pre-clinical studies regarding depression have demonstrated that NO inhibitors induce antidepressant-like effects in animal models such as the forced swim test (Reference Jefferys and Funder93–Reference Joca and Guimaraes95) and chronic mild stress (Reference Zhou, Hu and Hua96,Reference Mutlu, Ulak, Laugeray and Belzung97). Nonetheless, none of these drugs is available for clinical use so far. Confirming the link between ketamine effects and NO, two different studies have shown that the pre-treatment with the NO precursor l-arginine can block the effects of ketamine in rats exposed to the forced swim test (Reference Zhang, Wang and Shi98,Reference Liebenberg, Joca and Wegener99). Furthermore, the effects of a sub effective dose of ketamine were potentiated by a sub effective dose of the NO inhibitor L-NAME (Reference Zhang, Wang and Shi98). In addition, the effects of ketamine also relate to a reduction of the NO pathway activity in the hippocampus of rats (Reference Zhang, Wang and Shi98,Reference Liebenberg, Joca and Wegener99). Therefore, it seems that the reduction in NO activity in the brain is an important feature of ketamine’s antidepressant effect.

The second step, the increase of glutamate release, is proposed to happen through NMDAR blockade on GABAergic interneurons. This event would cause an inhibition of the GABAergic modulatory action over glutamatergic neurons, thus leading to a disinhibited state of the glutamatergic neurons (Reference Liu and Moghaddam100). Indeed, evidence shows that a low dose of ketamine increases the release of glutamate in the prefrontal cortex of rats, which is not seen with high doses of ketamine (Reference Moghaddam, Adams, Verma and Daly71). Therefore, a key action of ketamine seems to be the reduction of the NMDA drive of the glutamatergic neurotransmission and the increase of the amount of glutamate available to act on other targets such as the glutamatergic AMPAR (Reference Browne and Lucki7), which should be kept in mind for further discussion.

The third main action responsible for the effects of ketamine on depression is the increase of the activation of AMPAR. Different pieces of work show that pre-treatment with AMPAR antagonists can block the behavioural effects of ketamine and other NMDAR antagonists (Reference Li, Lee and Liu80,Reference Pereira, Romano, Wegener and Joca83,Reference Koike, Iijima and Chaki101,Reference Maeng, Zarate and Du102). Furthermore, reports show that AMPAR potentiators can induce antidepressant-like effects (Reference Li, Tizzano, Griffey, Clay, Lindstrom and Skolnick103,Reference Lindholm, Autio and Vesa104). Interestingly, monoaminergic antidepressants seem to be able to facilitate the glutamatergic transmission through AMPAR while decreasing NMDAR driven transmission (Reference Barbon, Caracciolo and Orlandi105,Reference Sanacora, Treccani and Popoli106). Thus, increasing the AMPA drive of the glutamatergic system seems necessary to produce the antidepressant effects of ketamine.

The second chain starts after the increased activation of the AMPAR, which is followed by a set of events and culminates on the activation of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR). Such events seem to occur through the activation of L-type voltage dependent calcium channels (L-VDCC), leading to increased release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which in turn, activates the tyrosine receptor kinase B (TrkB)–Akt–mTOR pathway. Data obtained from in vitro experiments show that the activation of AMPAR increases the release of BDNF dependently of L-VDCC (Reference Jourdi, Hsu, Zhou, Qin, Bi and Baudry107,Reference Lepack, Fuchikami, Dwyer, Banasr and Duman108), and recent evidence shows that the systemic injection of L-VDCC inhibitors can block the antidepressant-like effects of ketamine (Reference Lepack, Fuchikami, Dwyer, Banasr and Duman108). However, further studies are necessary to corroborate this evidence.

The interplay between the antidepressant effects of NMDAR antagonists and the BDNF pathway has been tested through different protocols. The antidepressant-like effects of ketamine and MK-801 in mice showed to be dependent on a fast increase of BDNF synthesis (Reference Autry, Adachi and Nosyreva81). Nonetheless, genetically modified animals that exhibit lower BDNF levels do not respond to ketamine when exposed to the forced swim test (Reference Liu, Lee, Li, Bambico, Duman and Aghajanian109). Corroborating such evidence, the infusion of an anti-BDNF antibody into the prefrontal cortex was shown to be capable of blocking the effects of ketamine (Reference Lepack, Fuchikami, Dwyer, Banasr and Duman108). Interestingly, ketamine abusers present increased serum levels of BDNF (Reference Ricci, Martinotti and Gelfo110).

After BDNF activation of TrkB, there is another important downstream molecular mediator of ketamine’s antidepressant effect; mTOR, a key protein involved in the control of cell growth and proliferation (Reference Li, Lee and Liu80,Reference Costa-Mattioli and Monteggia111). Initially, the NMDAR antagonist, MK-801, was shown to be capable of increasing the synthesis of synaptic proteins into the prefrontal cortex of rats in a way dependent on mTOR activation (Reference Yoon, Seo and Kim112). Posteriorly, it was demonstrated that the antidepressant-like effects of different NMDA antagonists as ketamine, Ro 25-6981 and LY 235959 are blocked by mTOR inhibition in the prefrontal cortex of rats exposed to the forced swim test (Reference Li, Lee and Liu80,Reference Li, Liu and Dwyer82,Reference Pereira, Romano, Wegener and Joca83). Ketamine was found to increase protein synthesis and spine density in the prefrontal cortex of rats, which could be blocked by the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin (Reference Li, Lee and Liu80). Thus, there is strong evidence supporting the idea that the antidepressant effects of ketamine depend on the BDNF–TrkB–mTOR pathway.

It is important to highlight that AMPARs might lead to mTOR activation through a more direct pathway, independently of BDNF and TrkB. In vitro data show that AMPAR from striatal neurons can influence neuronal plasticity and gene expression through the activation of MEK/ERK and phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathways, depending on Ca+2 influx (Reference Mao, Tang, Samdani, Liu and Wang113,Reference Wang, Tang and Parelkar114). Both MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways are the main mediators able to activate mTOR (Reference Costa-Mattioli and Monteggia111,Reference Nagahara and Tuszynski115). Furthermore, it has been reported that the fast antidepressant-like effects of ketamine and an AMPAR potentiator, LY 451646, induced an antidepressant-like effect without increasing the level of BDNF or the phosphorylation of TrkB into the hippocampus of mice (Reference Lindholm, Autio and Vesa104). Therefore, future studies may help clarify the role of such mechanisms on the antidepressant effects of fast-acting drugs.

One final mediator to be mentioned is glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3), which is a kinase involved in several cellular processes like cell signalling, proliferation, plasticity and apoptosis (Reference Grimes and Jope116), as it can also act by inhibiting mTOR (Reference Zoncu, Efeyan and Sabatini117). Evidence shows that ketamine can inhibit GSK-3 and that its antidepressant-like effects are dependent on this inhibition (Reference Beurel, Song and Jope118). Furthermore, the same study demonstrated that a high dose of lithium, a mood stabiliser inhibiting GSK-3, could induce an antidepressant-like effect in a similar way to ketamine (Reference Beurel, Song and Jope118). Similarly, Liu et al. and Chiu et al. showed that lithium and a specific GSK-3 inhibitor potentiated the synaptogenic and the antidepressant-like effects of an ineffective dose of ketamine (Reference Liu, Fuchikami, Dwyer, Lepack, Duman and Aghajanian119,Reference Chiu, Scheuing and Liu120). Most recently, researchers showed that ketamine’s inhibition of GSK-3 reduces the internalisation of AMPAR, thus reinforcing the effects of increasing the glutamatergic drive through AMPA transmission (Reference Beurel, Song and Jope118,Reference Beurel, Grieco and Jope121). However, the isolated use of a specific GSK-3 inhibitor failed to induce any antidepressant-like effect on mice exposed to chronic mild stress (Reference Ma, Dang and Jia122), which indicates that similar net effects as the ones promoted by ketamine are necessary to reproduce similar antidepressant actions. The role of GSK-3 as a target for new antidepressant drugs is promising, but more studies are necessary to understand its role on behavioural control mechanisms.

Regarding the aforementioned data, ketamine stimulated the research field of antidepressant drugs by highlighting the role of important biological markers involved in a fast and long-lasting antidepressant effect. At present, most of the ongoing work on new antidepressant treatments is investigating the manner in which the potential drugs interact with AMPAR, BDNF, TrkB, mTOR and most recently GSK-3.

State of the art

Ketamine brought new ideas to the research of the neurobiology of depression, but it is not a wonder drug. Its psychotomimetic effects and abuse potential are difficult to overlook, thus it is not suitable for wide clinical use (Reference Sanacora and Schatzberg62,Reference Caddy, Giaroli, White, Shergill and Tracy123). Furthermore, it is necessary to emphasise that more studies, with large-scale samples, long-term evaluation, repeated dosing, tolerance and safety assessment are needed to fill the gaps regarding our knowledge about the use of ketamine for depression. The scientific community has discussed these issues, since the off-label use of ketamine has been growing among depressed patients (Reference Sanacora, Frye and McDonald124–Reference Wilkinson and Sanacora126). Such practice is not recommended because important factors are still to be defined; like the most effective dose, treatment setting and an optimal administration pathway (Reference Sanacora, Frye and McDonald124–Reference Wilkinson and Sanacora126). It is plausible to consider that ketamine may never reach the market as an antidepressant, but it paved the way to the development of potential antidepressant drugs.

Ketamine brought science several steps closer to the development of new and improved antidepressant drugs by shedding light on several targets, which might provide agents without the same unfortunate side effects as ketamine. Thus, we will now discuss some of the most prominent drugs for depression treatment aiming targets evidenced by ketamine studies.

Besides ketamine, other NMDA antagonists are under consideration as new antidepressant drugs. Among these, the selective antagonists of the GluN2B subunit of the NMDAR deserve more attention. The compound Ro 25-6981 has induced anxiolytic and antidepressant-like effects in animal studies (Reference Li, Lee and Liu80,Reference Kiselycznyk, Jury and Halladay127), and such effects seem to be unaccompanied by psychotomimetic effects (Reference Lima-Ojeda, Vogt and Pfeiffer128). Another compound, CPP-101,606 (traxoprodil), induced antidepressant effects both in treatment-resistant individuals (Reference Preskorn, Baker, Kolluri, Menniti, Krams and Landen129) and in animals (Reference Poleszak, Stasiuk and Szopa130), but clinical data showed that it causes cardiac adverse effects (Reference Preskorn, Baker, Kolluri, Menniti, Krams and Landen129,Reference Lener, Kadriu and Zarate131). Most recently, another agent, MK-0657, was introduced and shown to have improved the mood of treatment-resistant individuals without inducing dissociative symptoms (Reference Ibrahim, Diaz Granados and Jolkovsky132). However, a phase-2 placebo-controlled trial (NCT02459236) did not reach the primary endpoint of improvement on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression with CERC-301 (former MK-0657) at doses of 12 and 20 mg/kg (Reference Lener, Kadriu and Zarate131). A recent report indicates that GluN2B antagonists tested in non-human primates might induce transient cognitive impairment (Reference Weed, Bookbinder and Polino133). Therefore, further investigations are necessary to confirm if these drugs can be applied for the open clinical treatment of depression.

Another interesting way to modulate the NMDAR is through the glycine site. Glycine acts as a co-agonist at the NMDAR by facilitating the receptor activation by glutamate (Reference Skolnick, Popik and Trullas134,Reference Paoletti, Bellone and Zhou135). Thus, drugs blocking or reducing the action of glycine could induce interesting behavioural effects like those of the NMDAR antagonists. In 1990, Trullas and Skolnick were the first to show that the systemic injection of a partial agonist of glycine site, ACPC, was able to induce an antidepressant-like effect in mice exposed to the forced swim test or to the tail suspension test (Reference Trullas and Skolnick69). Interestingly, recent studies have demonstrated that a glycine site modulator, Rapastinel (former Glyx-13), has interesting effects as a cognitive enhancer (Reference Rajagopal, Burgdorf, Moskal and Meltzer136,Reference Burgdorf, Zhang and Weiss137) as it also induces important pre-clinical and clinical antidepressant effects (Reference Burgdorf, Zhang and Nicholson138,Reference Burch, Amin Khan and Houck139). Rapastinel has been shown to induce antidepressant-like effects in animals which like ketamine involve AMPAR and mTOR signalling, long-term changes in synaptic plasticity and are not followed by psychotomimetic effects (Reference Burgdorf, Zhang and Weiss137,Reference Burgdorf, Zhang and Weiss140–Reference Moskal, Burgdorf and Stanton142). More importantly, Rapastinel has been a promising tool in clinical studies as it is in advanced phases of clinical trials and may represent the first fast-acting antidepressant drug to be approved for clinical use (Reference Moskal, Burgdorf and Stanton142–Reference Machado-Vieira, Henter and Zarate145).

Recent evidence pointed out that the metabolites of ketamine could play an important role in the observed antidepressant effects. Initially, ketamine is metabolised to norketamine, which was thought to be the main active product, since it is the only one able to induce anaesthesia like ketamine (Reference Leung and Baillie146). However, current evidence also shows that norketamine can induce antidepressant-like effects (Reference Salat, Siwek and Starowicz147). Additionally, it was demonstrated that the main ketamine metabolites are, in fact, the hidroxinorketamines (HNK) (Reference Zarate, Brutsche and Laje78,Reference Zhao, Venkata and Moaddel148) and that some of these HNK could be involved in the long-lasting effects of ketamine (Reference Zarate, Brutsche and Laje78,Reference Zanos, Moaddel and Morris149). Zanos et al. (2016) demonstrated that the ketamine metabolite 2R,6R-HNK exerts an antidepressant-like effect in a series of animal models for antidepressant activity, and that it does not induce any psychotomimetic effect (Reference Zanos, Moaddel and Morris149). Furthermore, they showed that the effects of 2R,6R-HNK involve (1) direct activation of AMPAR, (2) time dependent activation of the BDNF–mTOR pathway and (3) maintenance of synaptic potentiation (Reference Zanos, Moaddel and Morris149). Therefore, the use of ketamine metabolites may represent a new tool for the development of the next generation of fast-acting antidepressant drugs.

Another pharmacological tool that may be useful for the development of new antidepressant drugs is the positive modulation of AMPAR. As seen previously, the enhancement of the glutamatergic AMPAR-driven transmission is an important part for the fast and long-lasting effects of NMDAR antagonists, such as ketamine. However, given pharmacological matters, the use of agonists is difficult, mainly because of potential tachyphylaxis, since receptor potentiators are normally partial agonists (Reference Sanacora and Schatzberg62). Some AMPAR potentiators have shown promising antidepressant-like effects, as LY392098 (Reference Li, Tizzano, Griffey, Clay, Lindstrom and Skolnick103,Reference Farley, Apazoglou, Witkin, Giros and Tzavara150) and LY 451646 (Reference Lindholm, Autio and Vesa104). For instance, Org 26576 was tested in humans and presented interesting antidepressant effects (Reference Nations, Bursi and Dogterom151,Reference Nations, Dogterom and Bursi152), but it failed in phase-2 trials (Reference Machado-Vieira, Henter and Zarate145). Other AMPAR potentiators are under development or starting clinical trials (Reference Machado-Vieira, Henter and Zarate145,Reference Dutta, McKie and Deakin153); therefore, data presented in the future may confirm that these drugs will be useful for the treatment of depression.

Concluding remarks

Ketamine can be considered one of the most important drugs synthesised in the 20th century given its clinical and social impact over the years. Nonetheless, it remains relevant in the 21st century, given its great influence on behavioural research and depression treatment. In fact, the beneficial effects of ketamine on behaviour are not new but they were not considered relevant when first noticed, as reported by Dr. Edward Domino (Reference Domino53). Luckily, such effects were not ignored in the studies developed later.

All the data reviewed in the present paper demonstrate the importance of ketamine not only by shedding light on more targets which could potentially treat depression, but also by further elucidating the neurobiology of this disorder. Nevertheless, there are still many unanswered questions about the mechanism through which ketamine induces such remarkable antidepressant effects and how these mechanisms interact with other neurotransmission systems (Reference Sanacora and Schatzberg62). Several ongoing studies will help clarify the impact of the glutamatergic modulation per se or its interaction with monoaminergic, nitrergic and inflammatory systems, as the role of plasticity shifts into the complex grid of behavioural control (Reference Sanacora and Schatzberg62,Reference du Jardin, Muller, Elfving, Dale, Wegener and Sanchez68,Reference Rantamaki and Yalcin154). Finally, ketamine has rescued the interest in new treatments for depression, which was decreasing by the end of 1990s. Therefore, in the near future, there is a great hope of having better pharmacological treatments for depression available.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank CNPq (PDE – 203647/2014-9) for the funding provided. The authors also thank Fernanda Rodella, Karen J. Madsen and Maja C. Strand for proofreading the present paper. Authors’ Contributions: V.S.P. designed the review and reviewed all information regarding ketamine. V.A.H.S. reviewed all the information regarding the history of antidepressants.

Conflicts of Interest

None.