At the age of eight years, Daksha arrived in the UK from India speaking very little English. However, in 1984 she became the first student from her school to enter Medical School, as Daksha was offered a place at The Royal London Hospital Medical College. After a serious suicide attempt as a first year medical student, Daksha was diagnosed with depression, which was later changed to the diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder. As a consequence of her illness she spent much of her life as a medical student in hospital receiving medication and even received several courses of electroconvulsive therapy, during severe depression. When she was not in hospital, she would still be treated for her illness as an out-patient. However, despite suffering from such a debilitating illness, and in a testimony to her inner strength and self-belief, Daksha won a Medical Research Council scholarship for her BSc (Hons) in pharmacology. She won the David Reeve Prize in embryology, the Buxton Prize in combined anatomy, biochemistry and physiology, the Howard Prize in pharmacology and the Floyer Prize in history-taking. Despite hospitalisation for a hypomanic relapse in 1988, she distinguished herself by obtaining first place in all her exams at the end of that academic year.

On her elective to Cork in 1991, Daksha met and fell in love with radiographer David Emson. Despite hostility to their love, the relationship duly blossomed and they were married in 1992. After completing her House Officer jobs at the Royal London Hospital, Daksha was appointed to the United Medical and Dental Schools (UMDS) Training Rotation Scheme in psychiatry. She gained both Part I and Part II MRCPsych at first attempt; she received her MSc in Mental Health Studies in 1997, gaining a distinction for her dynamic psychotherapy project. She was very active in audit, administration, management and research. Her research interests were involved in community psychiatry and forensic psychiatry, where she presented her research in forensic psychiatry at the Royal College of Psychiatrists conference in Cardiff. She intended to publish her research in community psychiatry.

Daksha’s ambition was to practise as a community and rehabilitation psychiatrist, and she sought experience in all the major specialties within psychiatry to facilitate this goal. As a young forensic specialist registrar she found herself giving oral evidence as an expert witness at The Old Bailey. She was actively involved in teaching graduate and post-graduate psychiatry trainees on the UMDS Rotation Schemes; running the journal club in evidence-based psychiatry; lecturing on the MRCPsych Part I and II courses, and was an examiner for the mock exams for both Part I and II MRCPsych at Guy’s Hospital. Although she was undoubtedly an academic, Daksha always considered herself a ‘hands-on psychiatrist’. She pursued her special interest in the different aspects of psychotherapy, and trained as a psychodynamic psychotherapist and a cognitive analytical therapist.

Daksha was incredibly humble and unassuming in her academic achievements, and would be deeply embarrassed about discussing her achievements with friends and colleagues. She was strongly determined that her diagnosed mental illness would not hinder her ambition to become a respected psychiatrist. She undoubtedly achieved her ambition. However, this level of energy, dedication and commitment would often leave Daksha exhausted.

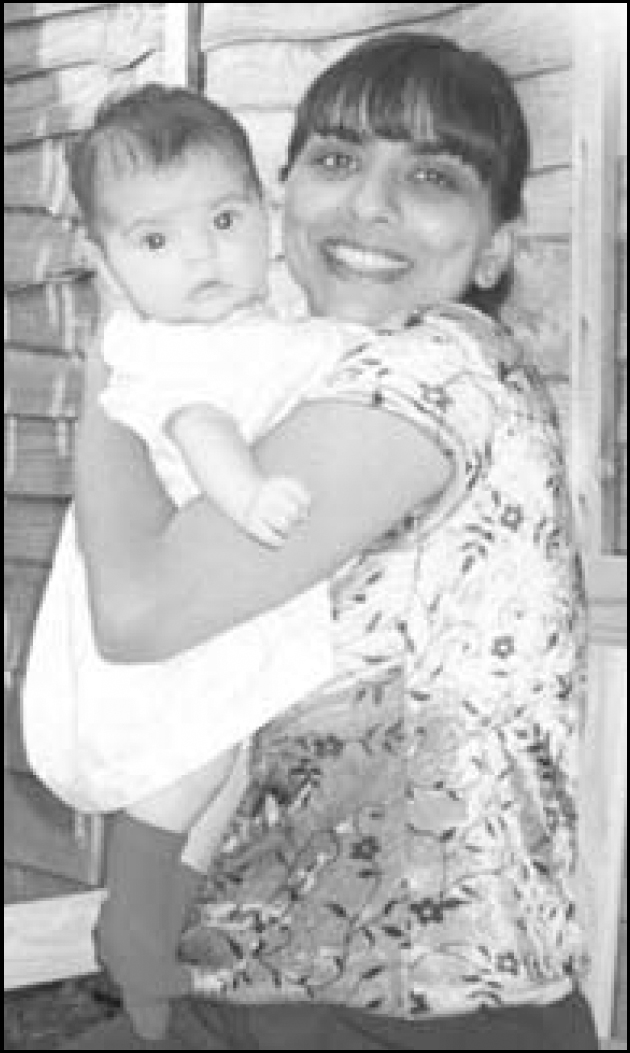

Daksha never experienced a relapse of her illness in the eight years of her married life. After stopping her medication for her bipolar illness to enable her to start a family, Daksha experienced three miscarriages in as many months, which included losing twins. Her first miscarriage was on board a Greek ferry, but in a testimony to her strength in character she wiped away the tears and taught herself Greek for the rest of the journey! However, we were blessed with the arrival of our much-loved beautiful baby daughter, Freya, on 4 July 2000.

Daksha was to take up her first consultant post in community and rehabilitation psychiatry in February 2001 at Oxleas NHS trust, on a part-time basis so that she could fulfil both roles as a mother and as a clinician. Regrettably, the day before she was to resume her medication, Daksha had become psychotic and in an act of ‘protecting our daughter’ she gave our daughter Freya back to God, where Daksha would also find herself being reunited with Freya nearly three weeks later (clinically described as an extended suicide). Because of Freya’s personality and bonding, together with Daksha’s care and attention as a wonderful mother, Freya never cried.

Her own mental illness enabled Daksha to become an exceptional psychiatrist, and she was most grateful for the care and treatment that she received from her carers. Daksha had the most extraordinary presence and empathy to everybody that met her. She was highly respected by her colleagues and by her patients. She was a loving and devoted mother and wife, and a truly remarkable clinician. In Daksha’s own words: ‘It’s not important what you do, but how you do it that is important’. She certainly practised what she preached!

The Royal College of Psychiatrists lost one of their finest daughters. However, the Independent Inquiry into the care and treatment of Daksha and Freya, will enable Daksha, even in death, to have a positive impact on the care and treatment of other mothers suffering with bipolar illness, and also on the care and treatment of other healthcare workers, stigmatised because of their diagnosed mental illness.

She leaves an honoured and privileged husband.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.