At first sight, these two volumes represent different views of the task of interpreting material culture: the first seems to announce a post-processual paradigm, emphasising the agency of objects and the ambivalence of meanings in the area of magical practice, whereas the second makes no overt claims about materiality while based firmly on museum objects. In fact, however, the differences between them are rather smaller than first impressions suggest.

The volume edited by Adam Parker and Stuart McKie began life as a panel organised by the former at the 25th TRAC meeting at Leicester in 2015, at which versions of five of the ten papers were delivered. An immediate inspiration was The materiality of magic, edited by Houlbrook and Armitage (Reference Houlbrook and Armitage2015), both of whom were then still, like Parker and McKie, doctoral or early career researchers. In their introduction, the editors make clear that a principal aim was to provide a materialist alternative to the reliance on texts in the sphere of magic in the Roman Empire, indeed nothing less than a “realignment of scholarly understandings of ancient magical practices” (p. 4). Wisely enough, neither editor is keen to offer a definition of ‘magical practices’, McKie inclining to equate magic roughly with individual efforts at increasing agency in specific critical situations, along the lines of the ‘Lived Ancient Religion’ project at Erfurt (e.g. Albrecht et al. Reference Albrecht2018), while Parker prefers inferring functional aims from abnormal material assemblages. A like-minded contributor even urges systematic scepticism of literary evidence on the grounds that it is “limited in world-view” (p. 33), a problem that apparently does not beset the modern researcher. In practice, however, many of the authors are by no means averse to citing Greek and Latin texts in order to establish meanings, all too aware that without such contextualisation one is rapidly left with little but speculation—expressions such as ‘likely’, ‘clearly could have been’, ‘may suggest’ and ‘we may speculate’ abound here, especially (and unsurprisingly) in relation to unique assemblages.

The overall rubric, then, is the construction of the agency of (selected) things. The ten contributions cover a fairly obvious range of topics: curse-tablets, amuletic stones, (apotropaic) images, depositional practices. Celia Sánchez Natalías makes a case for the specific value of the use of lead for Latin curse-tablets; McKie, with greater originality, tries to intuit the experience of physically making such an object, with labour understood as a form of investment. Idit Sagiv, Glynn Davis and Véronique Dasen each discuss different aspects of amuletic stones: Sagiv presents 13 unpublished gems from finger-rings in the collection of the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, emphasising the specific properties of the stones; Davis evokes the olfactory and ritual value of amber, ‘the tears of the black poplar’ (Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca 5.23.4) imported from the far North; Dasen provides both an afterword and a rapid sketch of gynaecological and child-protective amulets. As for images, Andrew Wilburn argues that the Cave canem mosaic at Pompeii is directed against the evil eye. In one of the most successful contributions, Alissa Whitmore, rather against the post-processual grain, uses a comparison with Thai amuletic phalli to emphasise the fundamental point that the more one knows about the ‘why’ of such objects, that is, the rationalisations offered by individuals for what such amulets ‘do’ and how they work, the more one realises that it is the institution, the practice, that matters rather than the explanations offered. She also suggests in relation to facts that typically archaeology alone can establish, namely distribution and incidence, that one significant aspect of object-agency may be rarity. The remaining three contributions are perhaps less convincing: Adam Parker surveys auditory effects provided by bells and other objects; Thomas Derrick explores the multiple possible evocations from the (unknown) substances contained in glass unguentaria; and Nicky Garland, while rightly complaining of the common tendency to distinguish ‘proper’ ancient medicine from magico-religious practices, gets rather lost in an inconclusive re-examination of the ‘Doctor's burial’ at Stanway.

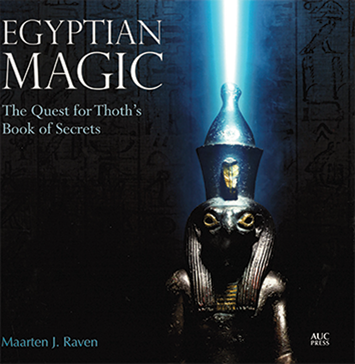

As Glynn Davis remarks, hunting for magic in the Roman West is a quite different kind of task than in the case of the East. Indeed, ancient Egyptian magic is largely co-extensive with Egyptian religion tout court. We are thus faced with an overwhelming number of often wonderfully evocative texts and artefacts—materiality in a quite different key. Maarten Raven's book is an excellent translation of a volume that he originally put together for an exhibition he organised in 2010–2011 at the major Egyptological museum of the Netherlands, the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden (RMO) in Leiden. Apart from tiny alterations, such as a slight re-arrangement of the material (pp. 102–107), and a few adjustments to the bibliography and index, the English version is identical to the Dutch even to the page-numbers, Raven having cleverly adjusted his translation to fit the space occupied by the images.

There is a fairly small number of books currently available that offer an introduction to Egyptian magic for a wider, non-Egyptological public. Scholars able to draw on the holdings of major museums are at a great advantage here. Among those in English, the most obvious comparison is with Geraldine Harris Pinch's Magic in ancient Egypt (Reference Harris Pinch2006), almost all of the 94 illustrations of which are from the British Museum's collection, although only 39 of them are in colour. By contrast, 99 per cent of Raven's 160 images, almost all from his own museum, are in brilliant colour, and the layout by Andre Klijsen has ensured that they are more attractively presented than was managed by the British Museum Press for Pinch. As for text, each offers competent and reliable surveys of the material, both artefactual and papyrological, but again, whereas Pinch's prose is dense and didactic, Raven's is light and lively—he has an admirable ability to impart knowledge without seeming to wag his finger. The final chapter, for example, offers a wry account of the more recent reception of ‘Egyptian’ magic in Europe: everyone has heard of the Tarot and the Order of the Golden Dawn, but I for one had never heard of the CIA's project in the 1980s to examine the destructive possibilities offered by the command of magic, nor of the scintillating glass pyramid used by the Dutch healer Jomanda.

The material is divided into 11 chapters, the first of which provides the wider framework of cosmogony, cosmology and mythology within which Heka (the Egyptian god of magic and medicine) had an essential, indeed fundamental, place alongside divine intellect and utterance. Fig. 8 (p. 19) shows a small green-glazed statue of him, now in the Louvre: on his ceremonial wig there sits the hindquarters of a seated lion—the hieroglyphic sign for ‘power’. This introduction is followed in turn by surveys, informed by a talent for picking out the telling detail. He first highlights different kinds of practitioners, from the lowly village wise-woman (reket), through healers specialising in snake-bites and scorpion-stings, all the way up to the privileged and learned chief lector-priest and his legendary models such as Imhotep or (Setne) Khaemwas; and carries on in the next chapter to describe selected rituals and some of the objects required for their performance. Although Raven does not address materiality explicitly, the focus throughout is upon the indissoluble nexus between fundamental conceptions of the world, say as a fluid medium or a multidimensional network; the range of actions that are meaningful within such a conception; the objects that are needed to realise those actions, and the consequent habitus; and the practised management of the strategies required by daily life in a highly stratified society based upon these objectifications. A tiny but telling example is the occasional practice in funerary contexts of removing, or not rendering, the legs of hieroglyphs depicting mammals or birds, where they are normally shown, in order to prevent the words they spelled from harming the occupant of the tomb.

Chapter 5, on books prescribing magical rituals and the learning required for their mastery and practical performance, shifts the focus decisively to the practice of magic by temple-priests, but also slips in a brief excursus on the history of the RMO's collection, with special reference to the role played by ‘Giovanni d'Anastasi’ in the nineteenth century. It is followed by four chapters devoted to healing and the alleviation of suffering, notably of the annual ‘plague of the year’ in high summer, temple-rituals for destroying enemies or ensuring fertility, protection of the tomb and the management of life after death, including the manufacture of model phoenixes to obtain resurrection. Chapter 10 then rapidly traces some of the developments into the Graeco-Roman and Coptic periods, noting both continuities and changes.

Comparison with the example of Egypt, with its long history of excavation, its extraordinary finds and its literary record, highlights the disadvantages under which archaeologists of the western provinces of the Roman Empire necessarily work. What is an appropriate discursive context? How applicable are Classical sources to acts and decisions in far-off Britannia? Do we need to handle widespread institutions differently from highly local, indeed unique, practices? Does the notion of ‘agency’ necessarily imply intentions at all? Merely emphasising materiality in relation to magical practices does not, I think, get us very far. We should rather be trying to distinguish between different registers of materiality, above all in their dialectic with immateriality, within specific distributions of power. This is all too obviously the case with Egypt, where the registers and the power-structures are relatively clear; but Parker and McKie's volume does hint at ways this might be achieved in the case of the very different practices in the western Roman Empire.