INTRODUCTION

Human cases of influenza A subtype H5N1 appear to cluster in families, a pattern which has led several authors to comment that host genetics may play an important role in susceptibility to A/H5N1 infection or disease [Reference van Kerkhove1–5]. This has potentially far-reaching implications, since the identification and subsequent characterization of genetic factors that have a strong influence on susceptibility to A/H5N1 disease would highlight key virus–host interactions necessary or contributory to infection or disease. Elucidating these key interactions has the potential to catalyse advances in areas such as the prediction of viral pathogenicity and the development of new or improved preventive and therapeutic interventions, which may be of relevance not only to zoonotic influenza but also to seasonal and pandemic influenza.

Since it re-emerged in 2003 A/H5N1 has received enormous attention, including the allocation of substantial financial resources for vaccine development and pandemic preparedness. Yet the reasons for its scarcity in humans, its poor ability to transmit between people, the clustering of cases and the risk factors for infection remain elusive; as does our ability to predict the likelihood that A/H5N1 may become a pandemic virus. Most research has focused on the viruses; through genotypic and phenotypic analysis and animal experiments using modified viruses, but the other half of the equation, the host, has been relatively neglected. Since it is epidemiological patterns that have stimulated consideration of host genetic factors, an important first step is to review whether the epidemiological patterns are consistent with a host genetic influence. Currently only two publications have explicitly examined the potential role of host genetics and human A/H5N1 infection. Pitzer et al. have looked at whether the observed clustering could be explained by chance alone [Reference Pitzer6]. Trammell & Toth have reviewed possible biological mechanisms of host susceptibility to influenza, using mostly data from murine models [Reference Trammell and Toth7]. We examine the epidemiological patterns of human A/H5N1 cases, their possible explanations, and review the evidence for a role for host genetics in susceptibility to influenza A/H5N1.

THE CASE IN FAVOUR OF A ROLE FOR HOST GENETICS

Familial aggregation of cases

Between 1 January 1997 and 25 November 2009 a total of 36 clusters of two or more laboratory-confirmed cases of A/H5N1 have been reported, with at least an additional 16 clusters of one confirmed case plus at least one probable case [Reference Sedyaningsih3, Reference Kandun4, Reference Olsen8–11] (Table 1). These 52 clusters account for 22% (103/463) of all laboratory-confirmed cases and only six of the 103 cases occurring in clusters did not have a genetic relationship to another case in the cluster. Although there is no data on the familial aggregation of other zoonosis for comparison, this degree of family clustering has surprised many people, especially since A/H5N1 is considered to only rarely transmit from person to person. Since familial aggregation is a hallmark of genetically determined diseases, genetic susceptibility to A/H5N1 infection is one hypothesis that might explain the familial aggregation. Unfortunately the apparent increased risk in relatives of affected cases compared to background risk has not been quantified and the large cluster in Karo, Indonesia was a missed opportunity to estimate the familial relative risk by comparing the risk in related and unrelated contacts of infected individuals. However, what we do know is that this cluster involved eight cases (seven laboratory-confirmed) in a single extended family residing in four households [Reference Yang12]. Nine family members slept in the same room as the primary case while the case was symptomatic and three of these nine (33%) developed A/H5N1 infection [13]. It is perhaps surprising that there were no unrelated cases despite multiple opportunities for infection of non-related contacts, including unprotected healthcare workers, and onset dates that stretched over a period of 3 weeks [14].

Table 1. Number of confirmed H5N1 cases and clusters by country

* As of 25 November 2009.

† A cluster is defined as at least two cases of clinically compatible illness with at least one case with laboratory-confirmed H5N1.

The relative absence of non-familial aggregation of cases

If all members of a community affected by A/H5N1 outbreaks in poultry are at equal risk then it would be more likely to observe pairs of cases of unrelated community members than to see household clusters [Reference Pitzer6]. Yet of the 103 confirmed cases occurring in 52 clusters, only six cases occurring in four clusters were not genetically related to any other case in the cluster [one husband and wife pair (Vietnam 2005); one healthcare worker (Vietnam 2005); one neighbour (Azerbaijan 2006); two children (Egypt 2009)] [11]. This pattern is important since it suggests either large differences in risk between families within affected communities, or large biases in the detection and reporting of family-based clusters compared to unrelated case clusters.

Related but unassociated cases

At least two incidents have occurred where genetically related individuals developed confirmed or probable A/H5N1 disease independently of one another.

In August 2004 a 25-year-old women from Hau Giang Province, southern Vietnam died from laboratory-confirmed A/H5N1. Both the 19-year-old brother of this case and their 23-year-old cousin died of severe pneumonia within a week of the confirmed case; specimens from these two cases were not tested for A/H5N1. The brother lived with the confirmed case but the cousin lived in a non-adjacent commune and investigations revealed that there had been no contact whatsoever between the cousin (and her immediate family) and the siblings (and their immediate family) in the week prior to the earliest onset of illness and the deaths. Local authorities concluded that there was no likelihood of a common point source of infection or of any other means of transmission of A/H5N1 between the cousin and the sibling cases. Therefore, the disease in the cousin seems to have occurred independently from the sibling cases.

In Thailand three related individuals suffered A/H5N1 infection during two different waves of the outbreak. The first case was a boy (C.P.) who died during the first wave of outbreaks in late 2003–2004 [Reference Chokephaibulkit15]. The mother of case C.P. also died of a respiratory illness at the same time as her son, but samples were not available for testing for A/H5N1 [Reference Olsen8]. The other two cases, a father and son (B.O and R.R.), were infected in the 2005 outbreak [Reference Uiprasertkul16]. Their family pedigree is shown in Figure 1. C.P. lived in the same province but a different district to B.O. and R.R.

Fig. 1. Family pedigree showing three H5N1 affected individuals, with infections separated by 2 years.

Given the scarcity of A/H5N1 disease, these incidents of related but apparently unconnected cases seem an improbable misfortune, unless relatives have an increased risk of A/H5N1 infection compared to the general population.

Exposure and risk are not well correlated

Although data from three case-control studies show that contact with dead or dying poultry is a significant risk factor for A/H5N1 infection, the proportion of cases that can be attributed to this factor is not high [Reference Dinh17–Reference Vong19]. About 25% of all confirmed clinical cases of H5N1 infection cannot recall any recent poultry exposure before illness onset and in many other cases the reported exposure to infected poultry is tenuous [Reference Dinh17, Reference Abdel-Ghafar20–Reference Yu22]. The largest case-control study published so far found that only 28% of all cases could be attributed to preparing or cooking sick poultry [Reference Dinh17]. The same study found no differences between affected and unaffected households in other poultry-handling practices, hygiene behaviour or in other putative risk factors such as the use of poultry fertilizer. This absence of obvious risky practices in many affected individuals and families juxtaposes starkly with the almost complete absence of clinical cases in groups who are known to have engaged in theoretically very high-risk behaviours, i.e. culling infected poultry flocks without personal protective equipment.

From 2003 to 31 January 2010, 49 countries have reported over 6660 outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza A/H5N1 in domestic poultry or wildlife to the World Organization for Animal Health and several hundred million poultry have died or been culled. These figures are a minimum, since only a proportion of all outbreaks are detected and reported. The number of people exposed to A/H5N1 as a result of reported and unreported outbreaks is not known but we do know that exposure to poultry is very common in many of the worst affected countries. One population-based study of more than 45 000 people in an A/H5N1-affected community in Vietnam found that 25·9% (11 755) lived in households where poultry were sick or had died [Reference Thorson23]. A community survey in Cambodia of 155 poultry-raising households in an A/H5N1-affected area identified poultry deaths in 102 households (66%), and 42 households (27%) were considered likely to have experienced an outbreak of A/H5N1 [Reference Vong19]. A larger survey in Cambodia estimated that most of the rural population has frequent contact with poultry and 52% regularly have a potentially high-risk exposure [Reference van Kerkhove1]. Therefore it likely that very large numbers of people, possibly millions, have been exposed to A/H5N1 since 2003 yet only 471 human cases have been reported globally over the same period. It can be safely assumed that these numbers, like poultry outbreaks, are a minimum as the clinical presentation is non-specific and few sites possess the capabilities to diagnose A/H5N1. Although a survey in two affected villages in Cambodia found serological evidence of subclinical A/H5N1 infection in seven (1%) out of 674 subjects [Reference Vong24], evidence from active surveillance and serological surveys of populations known to be exposed to A/H5N1 generally indicates that large numbers of cases are not being missed [Reference Vong19, Reference Beigel21, Reference Wang, Fu and Zheng25–Reference Dejpichai33]. While the sensitivity and reproducibility of serological assays for A/H5N1 infection is variable, many serological studies have used the gold standard of micro-neutralization assay with Western blot confirmation and therefore provide the best estimate currently available of A/H5N1 infection prevalence [Reference Rowe34, Reference Stephenson35]. The apparent low incidence of infection following exposure to sick poultry and the low risk in some intensely exposed groups indicates a substantial species barrier, but a barrier that seems to be much weaker in a small number of individuals and families [Reference Kuiken36].

Person-to-person transmission

Families live together in intimate contact and person-to-person transmission has been convincingly put forward as an explanation for two family clusters [Reference Ungchusak37, Reference Wang38] and an additional five reports have stated that it could not be ruled out in at least seven families [Reference Sedyaningsih3, Reference Kandun4, Reference Katz39–Reference Gilsdorf41]. The evidence for person-to-person transmission outside of the family is mixed. In the investigation of the 1997 Hong Kong cases, seropositive healthcare workers were identified, but none have been found in subsequent studies [Reference Schultsz28, Reference Liem and Lim31, Reference Apisarnthanarak42] and, as previously mentioned, non-familial clusters are rare. Person-to-person transmission of A/H5N1 clearly can occur but what is perhaps most interesting is the presence of limited intra-familial person-to-person transmission risk but its possible absence in other settings. This could be explained by the special intimacy of familial relationships but alternatively it could be an indicator of a genetic influence on risk; i.e. family members are at increased risk of person-to-person transmission because of a shared genetic susceptibility to infection from any source.

Biological plausibility

Certain animal species are more susceptible to H5N1 than other species and possible factors determining the host-range restriction of avian influenza viruses have been reviewed elsewhere [Reference Kuiken36, Reference Baigent and McCauley43, Reference Klempner and Shapiro44]. However, within-species differences also exist and in-bred mice strains exhibit large differences in their susceptibility to influenza infection [Reference Trammell and Toth7, Reference Srivastava45–Reference Boon47]. Indeed, differences in susceptibility of mouse strains to influenza infection, followed by mapping of the mouse disease loci and identification of the region on the human chromosome has led to the identification of the human Mx genes involved in response to viral infections [Reference Staeheli48–Reference Haller50]. Trammell & Toth have reviewed possible biological mechanisms of host susceptibility to influenza in the mouse model and similar host genetic influences on susceptibility to infection or disease might also exist in humans [Reference Trammell and Toth7]. In fact a recent study demonstrated genetic susceptibility to A/H5N1 in mice and called for studies of genetic susceptibility in humans [Reference Boon47]. However, to date no human genetic studies of susceptibility to influenza have been conducted, other than two genealogical studies, one of which identified a heritable predisposition to death from influenza [Reference Albright51, Reference Gottfredsson52].

Candidate host genes that may contribute to severe influenza illness can be proposed a priori from known virus–host interactions critical to infection, replication and pathogenesis [Reference Zhang53]. Alternatively, gene-expression profiling using microarrays may provide insights into genes associated with severe disease [Reference Pennings, Kimman and Janssen54]. The role of cell surface sialic acid receptors in the determination of host specificity of influenza viruses is well documented and therefore the genes encoding these receptors and their associated glycan modifications are potential candidates [Reference Gagneux55–Reference van Riel58]. Cytokine dysregulation has been shown to be a feature of A/H5N1 infection in clinical and animal studies [Reference de Jong59–Reference Maines61] and various aspects of innate immunity including collectin-like mannose-binding lectin, toll-like receptors (TLR 3, 7, 8), cytokines, chemokines, and interferon-inducible proteins such as MxA are also plausible candidates [Reference Tecle62–Reference Le Goffic68]. Interestingly, susceptibility to other viral respiratory pathogens has been traced to genes of the innate immune system [Reference Janssen69–Reference He73].

THE CASE AGAINST

Chance

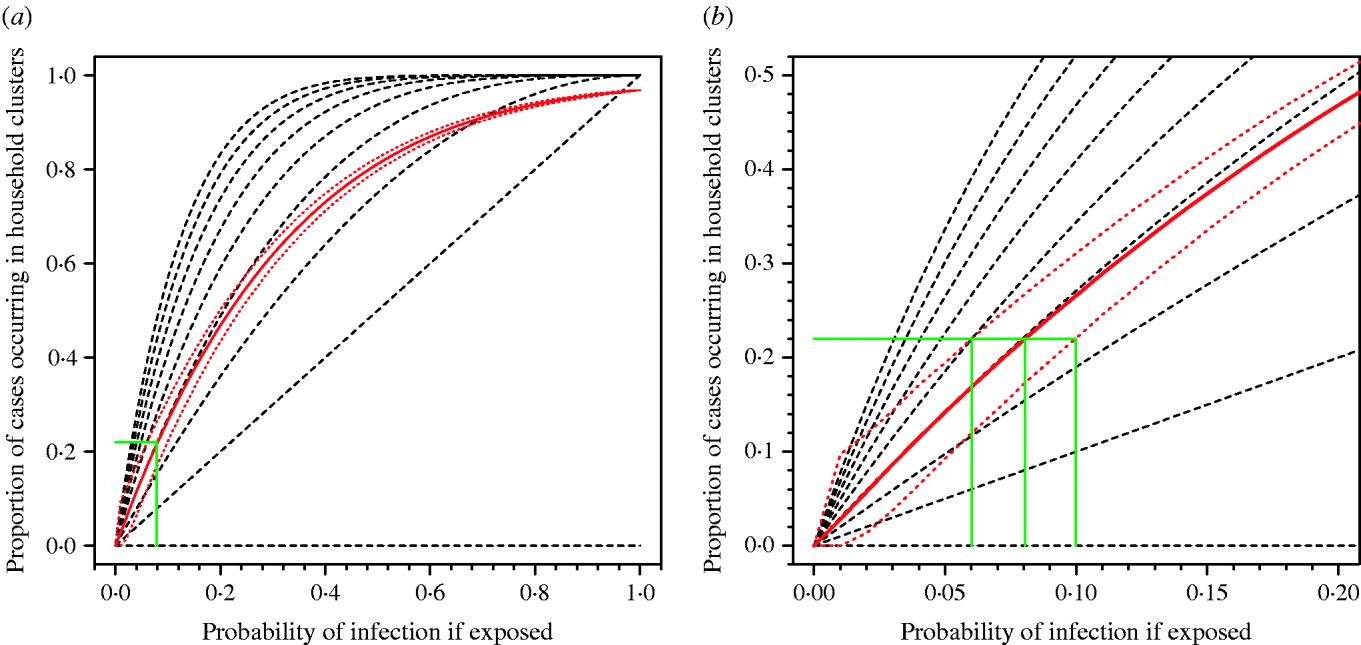

Pitzer et al. [Reference Pitzer6] have argued that the observed pattern of clustering of A/H5N1 cases can be explained by chance and does not provide evidence for a genetic effect. However, the application of similar methods using real data on household structures in Vietnam show that observing 22% of cases occurring in household clusters is consistent with a risk of infection following exposure of around 8% (95% prediction interval 6–10%) (Fig. 2). If the true risk of infection following exposure were 8%, the current 500 cases would be the result of exposure of only 6250 people globally over the past 5 years. This is an implausibly low number. The number of people exposed is certainly orders of magnitude higher, the risk of infection following exposure substantially lower than 8% and, therefore, the observation of 22% household clustering unlikely to be a probable outcome unless other factors are in play. Even if the risk of infection following exposure were 8%, and 22% of cases occurring in household clusters were simply a numerical result of this high risk, in any single affected community we would expect to observe around three sporadic cases for every case occurring in a household cluster (75% vs. 25%). As described above, we actually see few non-familial community clusters. The model of Pitzer et al. also only considered exposure of entire nuclear families with every family member at equal risk. This negates the influence of single or couple households, and occupational exposures outside of the home and therefore over-emphasizes the probability of familial clusters.

Fig. 2. Proportion of cases occurring in household clusters by probability of infection for different household sizes. (a) All data. (b) Enlargement of left-hand corner of panel (a). The broken black lines represent the modelled data for household sizes ranging from nine persons (top) to one person (bottom). The solid red line is the median estimate of the modelled data applying the observed range of household sizes in a Vietnamese cohort. Red dotted lines represent 95% prediction intervals for 10 000 simulations. The solid green lines show the probability of infection compatible with the observed clustering of about 0·22 for median estimate and 95% prediction intervals of model.

Bias

A key premise is that the observed clustering is a true reflection of the real situation – not simply an apparent pattern caused by biases. It is probable that multiple cases of severe pneumonia in healthy children or adults clustered in time and space are more likely than sporadic cases to be perceived as abnormal and therefore reported to the authorities. It is also true that following a first case which was severely ill or fatal, a second case in a family will rapidly seek medical attention; and indeed several of the reported clusters consist of a first fatality which is clinically suspicious of H5N1 and a second laboratory-confirmed case. So the observed level of clustering could be an artifact of differential ascertainment of clustered vs. sporadic cases. While this bias is bound to be operating to some extent, the question is whether it fully explains the clustering. Moreover, it might be expected that this ascertainment bias would apply similarly to community clusters of genetically unrelated cases as to family clusters.

Confounding

Familial risk does not necessarily mean genetic risk; families share their homes, food and behaviours with one another and therefore shared ‘high-risk’ exposures must be a strong contender to explain family clusters. Indeed, the paucity of community clusters of genetically unrelated human H5N1 cases has been suggested to be a reflection of risky behaviours which are unique to the affected families [Reference Pitzer6]. As noted above, unusual or risky practices have been identified but it has not been possible to attribute many cases to these behaviours since the behaviours are widespread in the community yet absent in many cases. It is certainly possible that behavioural factors partially or completely explain the epidemiological patterns but these have yet to be identified.

The scarcity of human cases despite widespread exposure clearly demonstrates a substantial barrier to humans acquiring infection, and much work has focused on unravelling the genetic and functional characteristics of the viruses which would explain these barriers [Reference Neumann, Shinya and Kawaoka74]. There are clear differences between virus strains in their ability to infect and cause severe disease in animal models but the viruses isolated from human cases occurring in family clusters have not been found to be substantially different from viruses causing sporadic human cases or poultry outbreaks [75]. The family clusters have occurred in 11 different countries as a result of infections with five different clades (0, 1, 2·1, 2·2, 2·3). So while virus factors are certainly critical in limiting the transmission of influenza A/H5N1 from animals to humans, current data do not allow us to attribute family clustering to viral factors.

CONCLUSION

The routinely available data on the epidemiology of human cases of A/H5N1 show some unusual patterns to which host genetic susceptibility offers a parsimonious explanation. Of course, this does not mean it is true; but it is both epidemiologically and biologically plausible and worthy of serious investigation. The importance of host genetics in infectious diseases is increasingly being recognized and explored [Reference Hill76–Reference Burgner, Jamieson and Blackwell78] and the relationship is usually a complex interaction between the pathogen, environmental influences and a range of innate and adaptive host factors. This poses difficulties for attempts to detect genetic influences on susceptibility to H5N1, since very large sample sizes are needed to detect complex or weak effects, yet the total number of cases is very small. However, a host genetics association study may potentially be informative if high-risk genotypes are present. A more powerful strategy would be a genome-wide linkage study in affected families, which could interrogate the whole genome without assuming any prior hypotheses on plausible candidate genes. Given the importance of understanding the key virus–host interactions underlying severe human influenza, a search for such genetic factors in A/H5N1 is worthwhile. However, the scarcity and widespread distribution of human case means that international collaboration is essential to conduct studies of genetic susceptibility to A/H5N1 disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the following for financial support: Wellcome Trust UK; Genome Institute of Singapore, Agency for Science Technology and Research (A*STAR); National Institutes of Health, South East Asia Infectious Diseases Clinical Research Network. Thanks are also due to Neal Alexander for help with Figure 2.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.