INTRODUCTION

Animals are co-infected by a wide range of parasite species (Graham, Reference Graham2008; Telfer et al. Reference Telfer, Birtles, Bennett, Lambin, Paterson and Begon2008; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Ostfeld and Keesing2015) whose interactions can affect both parasites and hosts across spatial and temporal scales (Rohani et al. Reference Rohani, Green, Mantilla-Beniers and Grenfell2003; Seabloom et al. Reference Seabloom, Hosseini, Power and Borer2009). Co-infecting parasite species may interact directly or indirectly within the host via direct competition, immune-mediated competition, or facilitation, which can enhance susceptibility to a co-infecting parasite, or result in a change in parasite virulence and/or within-host pathogenicity of one or more parasites (Petney and Andrews, Reference Petney and Andrews1998; Chaves et al. Reference Chaves, Kaneko and Pascual2009; Eswarappa et al. Reference Eswarappa, Estrela and Brown2012). At a population level, co-occurring infections may also impact the dynamics and persistence of infectious diseases through a variety of mechanisms that drive the emergence of human and/or animal diseases (Dobson, Reference Dobson1985; Pedersen and Fenton, Reference Pedersen and Fenton2007; Jolles et al. Reference Jolles, Ezenwa, Etienne, Turner and Olff2008; Diuk-Wasser et al. Reference Diuk-Wasser, Vannier and Krause2015). One mechanism is ecological interference, where changes in the susceptibility to one parasite due to population-level phenomena can impact the transmission dynamics in a host population, as in the case of measles outbreaks indirectly changing Bordetella dynamics (Rohani et al. Reference Rohani, Green, Mantilla-Beniers and Grenfell2003); a phenomenon previously described as heterologous immunity in places where different malaria species co-occur (Cohen, Reference Cohen1973; Richie, Reference Richie1988); or cross-immunity in places where different strains also co-exist (Bruce et al. Reference Bruce, Donnelly, Alpers, Galinski, Barnwell, Walliker and Day2000).

Experimental studies have shown that within-community parasite species richness is negatively associated with within-host parasite persistence (Hoverman et al. Reference Hoverman, Mihaljevic, Richgels, Kerby and Johnson2012; Johnson and Hoverman, Reference Johnson and Hoverman2012). Similarly, a host's environment (e.g. resources, climate) may influence co-infection and in turn, influence infection outcomes at the population and community level. For instance, in drought years, Babesia and canine distemper virus co-infections are frequent, and host mortality is increased; this is likely due to interactions between immunosuppression caused by canine distemper virus, and increased Babesia co-infections from increased numbers of questing ticks after drought-induced ungulate die-offs (Munson et al. Reference Munson, Terio, Kock, Mlengeya, Roelke, Dubovi, Summers, Sinclair and Packer2008). Habitat type and land use may also influence population-level patterns of parasite co-infection, as has been observed in spirochete co-infection in ticks (Sytykiewicz et al. Reference Sytykiewicz, Karbowiak, Chorostowska-Wynimko, Szpechcinski, Supergan-Marwicz, Horbowicz, Szwed, Czerniewicz and Sprawka2015). Studying patterns of vector-co infection at habitat and landscape scales [as reviewed in (Diuk-Wasser et al. Reference Diuk-Wasser, Vannier and Krause2015)] is a critical component of predicting and preventing zoonotic disease transmission risk.

In Panamá, the triatomine species Rhodnius pallescens (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) is an important vector of the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. Trypanosoma cruzi infects a wide range of domestic and wild mammal hosts, and is the causative agent of Chagas disease in humans. Prior studies in Panama have shown that T. cruzi infection in R. pallescens increases in response to anthropogenic disturbance (Gottdenker et al. Reference Gottdenker, Chaves, Calzada, Saldana and Carroll2012). Furthermore, R. pallescens is frequently co-infected by T. cruzi congeneric T. rangeli, a trypanosome species that is entomopathogenic in experimentally infected Rhodnius prolixus, but is not believed to cause disease in mammals (Groot and Hernandez Mora, Reference Groot and Hernandez Mora1947; Groot et al. Reference Groot, Renjifo and Uribe1951; Herbig-Sandreuter, Reference Herbig-Sandreuter1957; Añez, Reference Añez and Publication1981; Añez et al. Reference Añez, Velandia and Rodríguez de Rojas1985; Nieves and Añez, Reference Nieves and Añez1992; Peterson and Graham, Reference Peterson and Graham2016). Trypanosoma rangeli is epidemiologically important, as it shares 60% of its antigens with T. cruzi, and the two parasites can cross-react in serological tests (Guhl and Marinkelle, Reference Guhl and Marinkelle1982; Saldana & Sousa, Reference Saldana and Sousa1996a , Reference Saldana and Sousa b ; Guhl and Vallejo, Reference Guhl and Vallejo2003).

Recent studies have also shown that, like T. rangeli, T. cruzi infection can have negative impacts on vector fitness (Añez et al. Reference Añez, Molero, Márquez, Valderrama, Nieves, Cazorla and Castro1992; Fellet et al. Reference Fellet, Lorenzo, Elliot, Carrasco and Guarneri2014; Peterson et al. Reference Peterson, Graham, Dobson and Chavez2015), Additionally, triatomines (R. prolixus) experimentally co-infected with T. cruzi and T. rangeli have higher survival than insects infected with just one of the parasites (Peterson et al. Reference Peterson, Graham, Elliot, Dobson and Triana2016). This evidence that infection by one or both of the parasites can affect vector fitness suggests that these infections could influence vector population dynamics, the distribution and frequency of T. cruzi-infected Rhodnius spp. and, in turn, T. cruzi transmission to humans.

In this study, we evaluate how T. cruzi–T. rangeli co-infection in R. pallescens varies in response to anthropogenic landscape transformation. We propose two competing hypotheses to explain what is driving observed patterns of co-infection. First, we propose that a lower frequency of co-infected vectors than expected due to chance would suggest that individual or population-level interference between T. cruzi and T. rangeli (within their insect vectors or mammal hosts) structures co-infection patterns found in R. pallescens. In this scenario, co-infection patterns would be independent of landscape factors, and thus would not differ between landscape classes, nor be explained by spatial segregation of the parasites. We may also see a higher frequency of co-infected vectors, independent of habitat type, if infection by one parasite facilitates infection by another. Alternatively, a higher frequency of co-infection than expected by chance would suggest that habitats, acting as ‘templets’ of host community structure (Southwood, Reference Southwood1977), more strongly shape parasite transmission patterns. In this scenario, we would expect to see environmental or habitat-based differences in co-infection patterns across different landscape types (due to associated differences in the species composition of mammal hosts between habitats), and thus co-infection patterns would differ between landscapes.

METHODS

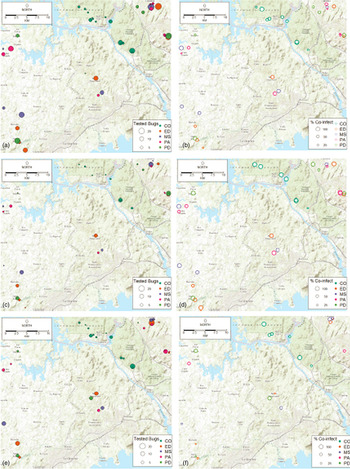

Rhodnius pallescens (N = 643) were captured from Attalea butyracea palm crowns during the wet season of 2007 (May–December) in a total of 45 study sites located to the east (Chilibre) and west (La Chorrera) of the Panamá Canal within the Panamá Canal Watershed. Sites (N = 45) were located in (a) contiguous late secondary tropical moist forests in Soberania National Park and (b) in four different habitats in anthropogenically transformed landscapes: mid-secondary forest remnants (seven sites), early secondary forest patches (eight sites), cattle pasture (eight sites) and peridomiciliary areas within 100 m of a human dwelling(seven sites). Five randomly selected palms were sampled from each site. Study site locations are shown in Fig. 1. Detailed descriptions of the moist tropical forest habitat types have been reported previously (Gottdenker et al. Reference Gottdenker, Calzada, Saldana and Carroll2011, Reference Gottdenker, Chaves, Calzada, Saldana and Carroll2012). Contiguous forests are fully protected sites within Soberania National Park, mid-secondary forest patches are remnants of original contiguous forest, generally around riparian areas, and early secondary forest patches refer to forest patches that were previously deforested, and in the early secondary forest stage of ecological succession. For all study sites, permission of the landowners and/or Soberanía National Park management was obtained. Permits for triatomine collection were obtained through the Autoridad Nacional de Ministerio de Ambiente (ANAM) of Panamá.

Fig. 1. Maps of infection prevalence with single Trypanosoma cruzi infection, single Trypanosoma rangeli infection, and T. cruzi–T. rangeli co-infection at study sites. CO, contiguous forest; ED, early secondary forest; MS, mid-secondary forest remnant; PA, cattle pasture; PD, peridomiciliary. (a) Total number of Rhodnius pallescens tested, (b) per cent of R. pallescens co-infected, (c) total number of adult bugs tested, (d) per cent of adult bugs co-infected. (e) Total number of nymphal bugs tested, (f) per cent of nymphal bugs co-infected.

To collect triatomines, Noireau traps were used in combination with direct searching. Three Noireau traps (Abad-Franch et al. Reference Abad-Franch, Noireau, Paucar, Aguilar, Carpio and Racines2000, Reference Abad-Franch, Ferraz, Campos, Palomeque, Grijalva, Aguilar and Miles2010; Noireau et al. Reference Noireau, Abad-Franch, Valente, Dias-Lima, Lopes, Cunha, Valente, Palomeque, de Carvalho-Pinto, Sherlock, Aguilar, Steindel, Grisard and Jurberg2002) were placed within the crown of each A. butyracea palm and checked the following day for R. pallescens (Gottdenker et al. Reference Gottdenker, Calzada, Saldana and Carroll2011, Reference Gottdenker, Chaves, Calzada, Saldana and Carroll2012). Traps were approved by the Gorgas Memorial Institute Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with Panamá's regulations for animal use. After recovering the baited traps, palm crowns were manually examined for triatomines by a skilled individual for 10 min. Palm crowns were accessed with a 20 feet tall ladder or by climbing the palm tree with a rope and harness climbing technique modified for palm trees.

After capture, triatomines were identified to the species level, following the key by Lent and Wygodzinsky (Reference Lent and Wygodzinsky1979) and classified by developmental stage. To diagnose trypanosome infection legs and wings of adults were removed, triatomine bodies were macerated (Calzada et al. Reference Calzada, Pineda, Montalvo, Alvarez, Santamaria, Samudio, Bayard, Caceres and Saldana2006; Pineda et al. Reference Pineda, Montalvo, Alvarez, Santamaria, Calzada and Saldana2008; Gottdenker et al. Reference Gottdenker, Chaves, Calzada, Saldana and Carroll2012) and DNA was extracted with a commercial kit (Promega, Madison, WI) following manufacturer instructions. Trypanosoma cruzi and T. rangeli DNA was amplified in a duplex PCR using the primer set Tc189Fw (5′-CCAACGCTCCGGGAAAAC-3′) and Tc189Rv3 (5′-GCGTCTTCTCAGTATGGACTT-3′) for T. cruzi and TrF3 (5′-CCCCATACAAAACACCCTT-3) and TrR8 for T. rangeli (5′-TGGAATGACGGTGCGGCGAC-3′) (Chiurillo et al. Reference Chiurillo, Crisante, Rojas, Peralta, Dias, Guevara, Anez and Ramirez2003). PCR products mixed with loading dye were run on a 1.5% agarose gel and T. cruzi (100 bp) and T. rangeli (170 bp) specific bands were observed. Negative controls of extraction and pcr as well as positive controls for pcr were run with known standards of T. cruzi and T. rangeli from cultured isolates from R. pallescens collected near areas of study as positive controls (single reactions) and T. cruzi and T. rangeli in the same tube as well as co-infected and singly infected samples from known-infected bugs.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were performed on singly infected and co-infected bugs for each habitat type. Confidence intervals for the proportion of bugs infected were calculated using a 1-sample proportions test with continuity correction. Chi-squared (χ2) analysis was used to evaluate univariate associations between triatomine stage (N3, N4, N5 and adult) and infection status (co-infected with T. cruzi, singly infected with T. cruzi or T. rangeli, or uninfected) as well as habitat and infection status. Association plots were used to visualize independence in two-way contingency tables for single/co-infection statuses among all bugs in each habitat, as well as bug stage and single/co-infection status using the vcd package in R (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Zeileis and Hornik2015). Maps were made of the overall number of R. pallescens bugs sampled and found infected. Generalized Estimating Equation models (GEEM) (Venables and Ripley, Reference Venables and Ripley2002) were used to evaluate the probability of vector infection in each habitat type using the Yags package (Carey, Reference Carey2004) in the R statistical computing environment (R Development Core Team, 2015).Logistic GEEM models with binomial errors were used because triatomines captured within each site were not independent from one another and we assumed that the correlation structure in the models was independent. An advantage to the logistic GEEM models is that empirical sandwich estimators can be used that result in valid confidence intervals for fixed effects, even if there is an incorrect or uncertain correlation structure (Venables and Ripley, Reference Venables and Ripley2002). For each binomial response variable (T. cruzi single infection, T. rangeli single infection, T. cruzi–T. rangeli co-infection), we began the analysis building a full model for each type of infection that included the following independent variables: habitat type, insect stage and covariates of T. cruzi or T. rangeli infection status (e.g. in the case where T. cruzi single infection was a response variable, T. rangeli was included as a co-variate in the full model and vice versa in the case of T. rangeli single infection as a response variable). A total of 632 bugs were available for this GEE analysis, less than the 643 tested for trypanosomes because 11 bugs were not identified to stage. The Quasilikelihood information criterion (QIC), a model selection metric analogous to the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), was used to identify the best fitting model among the set of candidate models for each infection type (Pan, Reference Pan2001).

RESULTS

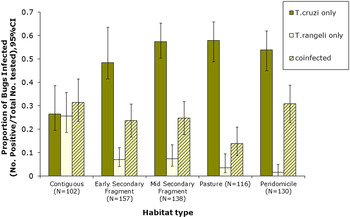

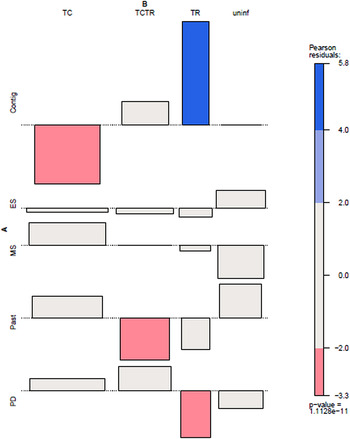

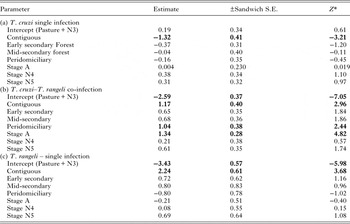

Figure 1 shows a map of the locations of the numbers of bugs tested (Fig. 1a), as well as the percentage of co-infected nymphs and adults (Fig. 1b), the number of adult bugs (Fig. 1c) and nymphs tested (Fig. 1e) and their co-infection (Figs 1d and 1f, respectively). In general, co-infections were more common in adult bugs (Fig. 1d), yet most samples were nymphs (Fig. 1e). Figure 2 shows patterns of the mean proportion of co-infected and singly infected bugs within and between each habitat type (Supplementary table A also shows the number of infected and co-infected bugs in each habitat type). Overall, across all sites, there was a significant association between habitat type and trypanosome infection in R. pallescens (χ2 = 77.74, df = 12, P-value = 1.11 × 10−11). The proportion of bugs singly infected with T. cruzi increased in disturbed habitats, while the proportion of bugs singly infected with T. rangeli markedly increased in contiguous forest as compared to anthropogenically disturbed habitats (Fig. 2). Association plots (Fig. 3) demonstrating habitat-related differences in infection status show that the frequencies of co-infected bugs were significantly lower than expected due to chance in cattle pasture. Trypanosoma rangeli single infections were significantly more frequent than expected due to chance in contiguous forests, and less frequent than expected in peridomiciliary habitats, and T. cruzi single infections were less than expected in contiguous forests (Fig. 3). Generalized estimating equations evaluating relationships between infection (co-infection, single infection with T. cruzi and T. rangeli, respectively), habitat and insect stage show that the odds of infection differed across habitats depending on the infection type (Table 1). Although overall triatomine infection status (single and co-infections) was more evenly distributed in contiguous forests, the odds ratio of single infections with T. cruzi in R. pallescens was greater in deforested habitats (mid-secondary forest remnants, early secondary forest patches, cattle pasture) compared with contiguous forests (Table 1). The odds of vector co-infection contiguous forests and peridomiciliary sites were significantly higher than in cattle pasture (Table 1). The odds of single infections with T. rangeli were significantly higher in contiguous forests relative to cattle pasture (Table 1). All other variables mentioned in the methods were left out by the process of model selection, or because models containing them did not converge numerically because of collinearity issues, i.e. some of the covariates had a nearly perfect correlation.

Fig. 2. Single and co-infection of Rhodnius pallescens with Trypanosoma cruzi and Trypanosoma rangeli in different habitat types (Contig, contiguous forest; ES, early secondary forest patch; MS, mid-secondary forest remnant; Past, cattle pasture; PD, peridomicile).

Fig. 3. Association plot of habitat and trypanosome co-infection patterns in Rhodnius pallescens. Contig, contiguous forest; ES, early secondary forest patch; MS, mid-secondary forest remnant; Past, cattle pasture; PD, peridomicile; TC, single infection with Trypanosoma cruzi; TCTR, co-infection with T. cruzi and Trypanosoma rangeli; TR, single infection with T. rangeli; uninf, uninfected. Pearson residual values of χ2 associations are shown to the right. Bar width corresponds to the square root of the expected counts, and the height of the bars are proportional to the Pearson Residual values.

Table 1. Parameter estimates for the logistic generalized estimating equation models explaining infection status for Rhodnius pallescens singly infected with Trypanosoma cruzi only (a), co-infected with T. cruzi and Trypanosoma rangeli (b), singly infected with T. rangeli (c). Sites were the clustering factor in the analysis.

* Significant (P < 0.05) when |“Z”| > 1.96, Significant parameters are in bold.

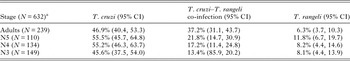

General stage-specific patterns of trypanosome infections are shown in Table 2. Overall, there was a significant association between triatomine stage and infection status (non-infected, co-infected, singly infected with T. cruzi, singly infected with T. rangeli) (χ2 = 63.46, df = 7, P-value = 2.877 × 10−10). Generalized estimating equations showed that stage was only significantly associated with infections in the case of co-infections (adults were more likely to be co-infected than nymphs) (Table 1).

Table 2. Stage-specific patterns of Rhodnius pallescens single and co-infections with Trypanosoma cruzi and Trypanosoma rangeli across all habitat types.

a 632 of 643 total bugs examined by PCR were identified to stage.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that patterns of single and co-infection of R. pallescens with T. cruzi and T. rangeli differ as a function of habitat type. Trypanosoma cruzi single infection frequency was markedly higher in anthropogenically disturbed habitats, and this was supported by its greater association with mid-secondary forest fragments, cattle pasture, and peridomiciliary sites and less frequent than expected occurrence in contiguous forests (Fig. 2, Table 1). On the other hand, T. rangeli single infection frequency was significantly greater than expected in contiguous forests. Trypanosoma cruzi and T. rangeli co-infection seemed to take on occurrence patterns of both infections, as co-infection was significantly more likely to occur in contiguous forests and peridomiciliary sites, and least likely in pasture habitats (Table 1).

One potential explanation for the habitat-related difference in patterns of trypanosome infections in triatomines is that anthropogenic disturbance can lead to differences in host community structure. This in turn can lead to changes in the principal mammalian reservoir of T. cruzi in each habitat type, and the hosts that are coming into contact with the triatomine vectors. In theory (Dobson, Reference Dobson2004; Chaves et al. Reference Chaves, Hernandez, Dobson and Pascual2007; Roche et al. Reference Roche, Rohani, Dobson and Guegan2013) and in practice, host community structure and/or variation in contact with hosts of varying competence can influence vector infection prevalence in a wide variety of vector-borne disease systems, including West Nile Virus (Loss et al. Reference Loss, Hamer, Walker, Ruiz, Goldberg, Kitron and Brawn2009; Hamer et al. Reference Hamer, Chaves, Anderson, Kitron, Brawn, Ruiz, Loss, Walker and Goldberg2012), Chagas disease (Kjos et al. Reference Kjos, Snowden and Olson2009; Gottdenker et al. Reference Gottdenker, Chaves, Calzada, Saldana and Carroll2012; Gurtler et al. Reference Gurtler, Cecere, Vazquez-Prokopec, Ceballos, Gurevitz, Fernandez Mdel, Kitron and Cohen2014; Gurtler and Cardinal, Reference Gurtler and Cardinal2015) and a variety of mosquito-borne pathogens (Chaves et al. Reference Chaves, Harrington, Keogh, Nguyen and Kitron2010). There is evidence of differential mammalian host competence for T. cruzi across taxa, but less is known about mammal host competence for T. rangeli. Trypanosoma rangeli infection has been frequently found in Pilosa (sloths and tamanduas) (Zeledon et al. Reference Zeledon, Ponce and Murillo1979; Miles et al. Reference Miles, Arias, Valente, Naiff, de Souza, Povoa, Lima and Cedillos1983; Dereure et al. Reference Dereure, Barnabe, Vie, Madelenat and Raccurt2001; Dias et al. Reference Dias, Quartier, Romana, Diotaiuti and Harry2010; De Araujo et al. Reference De Araujo, Boite, Cupolillo, Jansen and Roque2013) and their vectors. Blood meal analysis of R. pallescens vectors (Gottdenker et al. Reference Gottdenker, Chaves, Calzada, Saldana and Carroll2012) showed that Pilosa (sloth and tamandua) blood meals are present across all habitats, tamandua, sloth and primate blood meals dominate in R. pallescens captured in primary forests, and sloth blood meals are relatively common in all habitats. This suggests that sloths may be commonly infected with T. rangeli across landscape types, and is in accordance with previous observations in Panamá, where sloths were frequently infected with T. rangeli (Herrer and Christensen, Reference Herrer and Christensen1980). Although T. rangeli has been isolated from a wide range of vertebrate taxa (Miles et al. Reference Miles, Arias, Valente, Naiff, de Souza, Povoa, Lima and Cedillos1983), including sloths, non-human primates, bats, rats, and humans, the role different mammal species play in T. rangeli transmission is not well known, and one report states that there are no particular T. rangeli-specific vertebrate host associations (Maia Da Silva et al. Reference Maia Da Silva, Junqueira, Campaner, Rodrigues, Crisante, Ramirez, Caballero, Monteiro, Coura, Anez and Teixeira2007).

Our finding of significantly increased infection prevalence with T. rangeli in contiguous forests and increased odds of infection in forest fragments, i.e. mid-secondary and early secondary (Table 1) suggests that there may be some similarities in the host community composition or the identity of species coming into contact with vectors between these habitat types. Single infections with T. cruzi were more likely in triatomines captured in anthropogenically disturbed sites such as in cattle pasture, mid-secondary forest remnants and peridomiciliary sites, where triatomines are also more likely to come in contact with ‘anthropic’ species that are highly competent for T. cruzi, such as opossums (Didelphis marsupialis and Metachirus nudicaudatus). Previous studies show a positive association with T. cruzi infection in R. pallescens and opossum blood meal frequency (Gottdenker et al. Reference Gottdenker, Chaves, Calzada, Saldana and Carroll2012).

Trypanosome co-infection patterns within triatomine vectors could be related to potential interactions between trypanosome species within vectors and/or hosts. Laboratory studies have shown that infection with one species of trypanosome in the vertebrate host may lead to lower infection rates with the second congeneric parasite due to an immunoprophylactic effect of infection of the first parasite. For instance, laboratory mice injected with epimastigotes of T. rangeli developed a lower parasitaemia upon challenge with a virulent T. cruzi strain, which led to decreased severity of disease outcomes, and 100% survival of all mice (Palau et al. Reference Palau, Mejia, Vergara and Zuniga2003; Basso et al. Reference Basso, Moretti and Fretes2008). Domestic dogs vaccinated with T. rangeli and subsequently challenged with T. cruzi had less parasitaemia and lower rate of infection to bugs (Basso et al. Reference Basso, Castro, Introini, Gil, Truyens and Moretti2007). However, we did not find significantly lower than expected levels of T. cruzi–T. rangeli co-infection in triatomines at a landscape or habitat level with the exception of cattle pastures (Fig. 1), lending little support to our initial hypothesis that ecological interference (competition, indirect interactions) or immunological interference (cross-immunity) between T. cruzi and T. rangeli, drive single and co-infection patterns. Regardless, immunologically mediated interactions between T. cruzi and T. rangeli may occur within vectors, such as a previous infection with T. rangeli that may facilitate T. cruzi infection and/or replication in the vector. Further studies of trypanosome co-infection in wild vectors and hosts would help understand other potential mechanisms driving vector infection patterns.

In situ, mammal co-infection with T. cruzi and T. rangeli is relatively common in Neotropical wildlife where both parasites circulate between vectors and mammalian hosts (Christensen and de Vasquez, Reference Christensen and de Vasquez1981; Miles et al. Reference Miles, Arias, Valente, Naiff, de Souza, Povoa, Lima and Cedillos1983; Yeo et al. Reference Yeo, Acosta, Llewellyn, Sanchez, Adamson, Miles, Lopez, Gonzalez, Patterson, Gaunt, de Arias and Miles2005; Da Silva et al. Reference Da Silva, de Camargo, dos Santos, Massafera, Ferreira, Postai, Cristovao, Konolsaisen, Bisetto, Perinazo, Teodoro and Galati2008). It is possible that lower co-infection rates in cattle pastures may be due to a lower availability of mammal hosts of T. rangeli or co-infected vertebrates, or fewer contacts between these mammals and the bugs. Further research into the relative competence in different wild and domestic mammal species found across deforestation gradients for T. cruzi and T. rangeli is important to fully understand vector co-infection. Xenodiagnostics, a common means to assess reservoir competence, may be difficult in rare, evasive and/or cryptic species. In this case, indirect methods, such as molecular blood meal analysis in combination with extensive host sampling, may be important in inferring relative host competence and its role in vector infection prevalence.

In terms of potential parasite interactions within the vector, we found that co-infections with T. cruzi and T. rangeli increased with stage (Tables 1 and 2), with adults being the stage with highest predicted odds of co-infection (Table 2). In R. prolixus, co-infection with T. cruzi and T. rangeli results in increased vector fitness (Peterson, Reference Peterson2015). If R. pallescens responded similarly to co-infection, then the positive association of adult bugs and co-infection may potentially be the result of co-infection conferring a survival advantage to and/or throughout adulthood in these bugs.

Another potential explanation for this result is that co-infection allows for more virulent T. rangeli strains to persist in vector populations. Trypanosoma rangeli has been observed to negatively affect the feeding behaviour and life history of some species of experimentally infected Rhodnius (Watkins, Reference Watkins1971a , Reference Watkins b ; Añez, Reference Añez1984; Añez and East, Reference Añez and East1984; Añez et al. Reference Añez, Molero, Márquez, Valderrama, Nieves, Cazorla and Castro1992; Kollien et al. Reference Kollien, Schmidt and Schaub1998; Eichler & Schaub, Reference Eichler and Schaub2002; Schaub, Reference Schaub2006; Maia Da Silva et al. Reference Maia Da Silva, Junqueira, Campaner, Rodrigues, Crisante, Ramirez, Caballero, Monteiro, Coura, Anez and Teixeira2007; Vallejo et al. Reference Vallejo, Guhl and Schaub2009). Thus, it is possible that higher single T. rangeli infection rates in contiguous forests act to regulate vector populations. A moderate decline of T. rangeli infection in deforested landscapes may cause ecological release, allowing for increased reproductive success of R. pallescens in deforested landscapes, as previous studies have shown higher vector abundance in deforested habitats (Gottdenker et al. Reference Gottdenker, Calzada, Saldana and Carroll2011). Currently, R. pallescens occupancy rates in A. butyracea palms in Panamá are the highest recorded among triatomines infesting palms throughout Latin America (Abad-Franch et al. Reference Abad-Franch, Lima, Sarquis, Gurgel-Goncalves, Sanchez-Martin, Calzada, Saldana, Monteiro, Palomeque, Santos, Angulo, Esteban, Dias, Diotaiuti, Bar and Gottdenker2015). Studies of the relative T. cruzi and T. rangeli parasite loads in single and co-infected R. pallescens, and of the impacts of trypanosome infection on R. pallescens fitness and pathogenicity at individual and population levels are necessary in order to better understand potential impacts of trypanosome infection patterns on R. pallescens population dynamics.

To summarize, we show evidence that anthropogenic land use and habitat type is related to patterns of single and co-infection with T. cruzi and T. rangeli in the triatomine bug species R. pallescens. These findings have implications for our understanding of Chagas disease infection dynamics and the role that co-infections may play on vector and host population dynamics at a population and landscape level.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/pao.2016.9.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Humberto Membache and Jose Montenegro for assistance with field work and Roberto Rojas for laboratory assistance and expertise in R. pallescens stage identification. We thank local landowners in La Chorrera and Chilibre, and the Wounann Community of San Antonio for permission to collect insects on their land. Thanks to the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, the Autoridad Nacional del Medio Ambiente (ANAM) and park staff at Soberania National Park for their institutional assistance.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

L.F.C. is supported by Nagasaki University (Programme for Nuturing Global Leaders in Tropical and Emerging Communicable Diseases).

DISCLOSURE

Funding sources have not officially endorsed this publication and the views expressed herein may not reflect their views.