1. Introduction

Psychosis has been found to be associated with linguistic deficits [1–Reference Underwood, Kumari and Peters3] and poorer social and clinical outcomes [Reference Wilcox, Winokur and Tsuang4, Reference Roche, Segurado, Renwick, McClenaghan, Sexton and Frawley5]. The central role of language in the development of schizophrenia (SKZ) has been first hypothesized by Crow [Reference Crow6] who correlated the origin of psychotic symptoms with an altered hemispheric lateralization [Reference Crow7]. Furthermore, language comprehension deficits have been observed in the premorbid phase of SKZ [Reference Condray, Steinhauer and Goldstein8], further suggesting that linguistic assessment is important for predicting the development of psychosis [Reference Roche, Segurado, Renwick, McClenaghan, Sexton and Frawley5, 9–Reference Fuller, Nopoulos, Arndt, O’Leary, Ho and Andreasen11]. Additionally, syntactic deficits have been found in both First Episode Psychosis (FEP) patients [Reference Thomas, Leudar, Newby and Johnston12] and in individuals at high-risk for psychosis [Reference Solomon, Olsen, Niendam, Ragland, Yoon and Minzenberg13].

Moreover, another pressing issue of clinical research is represented by the investigation of similarities and differences between affective and non-affective psychosis in the linguistic domain [Reference Lott, Guggenbühl, Schneeberger, Pulver and Stassen14]. Interestingly, although speech deficits have been observed in both affective and non-affective FEP [Reference Kravariti, Reichenberg, Morgan, Dazzan, Morgan and Zanelli15, Reference Xu, Hui, Longenecker, Lee, Chang and Chan16], syntactic comprehension abilities in these patients have not yet been clearly explored [Reference Kravariti, Reichenberg, Morgan, Dazzan, Morgan and Zanelli15]. In general, language is generally divided in comprehension processing and syntactic processing. Comprehension has been described as sufficient vocabulary and knowing the meanings of enough words, while syntax has been described as set of rules, specific for each language, used to combine words in sentences, each word requiring for the generation of well-formed sentences [Reference Bellani and Brambilla17].

Although only a few behavioral studies explored linguistic abilities in FEP patients, they have been consistently investigated in both patients with SKZ and BD. Indeed, two previous studies from our group explored the linguistic performance in chronic psychotic patients [Reference Tavano, Sponda, Fabbro, Perlini, Rambaldelli and Ferro18, Reference Perlini, Marini, Garzitto, Isola, Cerruti and Marinelli19]. In particular, Tavano et al. [Reference Tavano, Sponda, Fabbro, Perlini, Rambaldelli and Ferro18] showed that patients with SKZ were significantly less able to produce appropriate interpretations, indicating the presence of abnormal pragmatic inferential abilities.

Also, the presence of pragmatic deficits in SKZ was further confirmed by a more recent study carried out by Bambini et al. [Reference Bambini, Arcara, Bechi, Buonocorec, Cavallaro and Bosia20], which reported altered pragmatic abilities, especially in comprehending discourse and non-literal meanings, in 77% of their patients with SKZ, ultimately suggesting that these abilities might be considered a core feature of SKZ.

Similarly, Perlini et al. [Reference Perlini, Marini, Garzitto, Isola, Cerruti and Marinelli19] suggested that the syntactic receptive verbal abilities were impaired in both chronic SKZ and BD, being, however, more severe and generalized in SKZ than in BD. Also, impairments in syntactic abilities were suggested by Moro et al. [Reference Moro, Bambini, Bosia, Anselmetti, Riccaboni and Cappa21] in patients with SKZ while processing of an anomaly detection task, which allow to investigate either the syntactic or semantic knowledge. The authors also reported that the syntactic impairments were independent from cognitive abilities and psychopathological measures.

Interestingly, these studies further aligned with the evidence reported by several other independent studies, which showed that patients with SKZ had severe and generalized deficits in terms of language impairments [Reference Crow6, Reference Crow7, 22–Reference Strik, Dierks, Hubl and Horn25].

Therefore, it seems that language abilities are important to be studied in psychosis, especially because language is a complex dynamic cognitive system, which brings to integration of multiple levels of linguistic and cognitive processing [Reference Spalletta, Tomaiuolo, Marino, Bonaviri, Trequattrini and Caltagirone26]. Indeed, psychotic patients showed word-finding difficulties and lexical processing impairments [Reference Iwashiro, Koike, Satomura, Suga, Nagai and Natsubori27] as well as they have the speech usually filled with irrelevant pieces of information and derailments [Reference Marini, Spoletini, Rubino, Ciuffa, Bria and Martinotti28].

In this context, this study aims to compare, for the first time, the linguistic abilities involved in syntactic comprehension in a large group of FEP patients and healthy controls (HCs), by considering both affective (FEP-A) and non-affective (FEP-NA) psychosis. In particular, we expected that a) FEP patients would show deficits in linguistic performance compared to HCs and b) FEP-NA patients would display more severe disturbances compared to both FEP-A and HCs.

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects

Patients were recruited in the frame of the ‘Genetics Endophenotypes and Treatment: Understanding early Psychosis’ (GET UP) Study (see Ruggeri et al. [Reference Ruggeri, Bonetto, Lasalvia, De Girolamo, Fioritti and Rucci29, Reference Ruggeri, Bonetto, Lasalvia, Fioritti, De Girolamo and Santonastaso30] for a detailed description of subjects’ enrolment). ICD-10 diagnoses were obtained after 9 months from the first contact with participating psychiatric services using the Item Group Checklist of the Schedule for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (IGC-SCAN) [Reference World Health Organization31]. Overall, 218 FEP patients and 106 HCs were evaluated. Among FEP, 166 were diagnosed with non-affective psychosis (FEP-NA) and 52 with affective psychosis (FEP-A). Specifically, for FEP-NA patients the diagnoses were schizophrenia (F20; N = 64), schizotypal disorder (F21; N = 4), delusional disorder (F22; N = 33), brief psychotic disorder (F23; N = 33), schizoaffective disorder (F25; N = 20), unspecified psychosis not due to a substance or known physiological condition (F29; N = 12). For FEP-A patients the diagnoses were mania with psychotic symptoms (F30.2; N = 13), bipolar affective disorder (F31; N = 6), bipolar affective disorder, current manic episode without psychotic symptoms (F31.1; N = 1), bipolar affective disorder, current manic episode with psychotic symptoms (F31.2; N = 4), bipolar affective disorder, current episode of severe depression with psychotic symptoms (F31.5; N = 1), bipolar affective disorder, current mixed episode (F31.6; N = 2), bipolar affective disorder, unspecified (F31.9; N = 2), mild depressive episode (F32; N = 1), severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms (F32.3; N = 22). Symptoms were assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) [Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler32], which is formed by one total score (PANSS-Total) and three sub-scales evaluating positive symptoms (PANSS-Positive), negative symptoms (PANSS-Negative) and general psychopathology (PANSS- Psychopathology), the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) [Reference Hamilton33], and the Bech–Rafaelsen Mania Rating Scale (BRMRS) [Reference Bech, Rafaelsen, Kramp and Bolwig34]. Also, the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) [Reference American Psychiatric Association35] was administered. Finally, the Brief Intelligence Test (TIB) [Reference Colombo, Sartori and Brivio36] was used to obtain a measure of the Intelligence Quotient (IQ). Patients with other mental and behavioural disorders, alcohol or substance abuse in the six months preceding the assessment, history of traumatic head injury, neurological or medical disease and mental retardation were excluded from the study. Notably, 99 out of 218 FEP patients (27 FEP-A and 72 FEP-NA) were drug-free. In contrast, 116 FEP patients (23 FEP-A and 93 FEP-NA) were taking different antipsychotic medications, either typical or atypical, and 3 FEP patients were taking only antidepressants (2 FEP-A and 1 FEP-NA). Specifically, FEP-A patients were taking haloperidol (N = 1), aripiprazole (N = 4), olanzapine (N = 8), paliperidone (N = 1), quetiapine (N = 5), risperidone (N = 6), and ziprasidone (N = 1). In contrast, FEP-NA were taking: haloperidol (N = 9), aripiprazole (N = 14), clozapine (N = 1), perphenazine (N = 2), olanzapine (N = 28), paliperidone (N = 8), quetiapine (N = 6), risperidone (N = 31) and ziprasidone (N = 1). With regards to antidepressants, three patients were taking only sertraline (N = 2, FEP-A) or paroxetine (N = 1, FEP-NA). Finally, within the groups of FEP-A patients, 11 were taking antidepressants or mood stabilizers in association with antipsychotics. HCs were recruited by word of mouth and leaflets. Subjects with a history of psychiatric symptoms, also in first degree relatives, were excluded from the study. All participants had Italian as native language. The GET UP was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Azienda Ospedaliera of Verona (http://www.ospedaliverona.it/Istituzionale/Comitati-Etici/Sperimentazione) on 6 May 2009 (Prot. N. 20406/CE, Date 14/05/2009), and by the ethics committee of each participating unit [Reference Ruggeri, Bonetto, Lasalvia, De Girolamo, Fioritti and Rucci29]. All participants signed inform consent after having understood all issues involved in the study design.

2.2 Syntactic comprehension measures

A multiple choice test of comprehension of syntax was administered to all participants. In particular, an adapted computer based version of the ‘Test di Comprensione Grammaticale per Bambini’ (TCGB) [Reference Chilosi and Cipriani37] assessing syntactic comprehension was used. This test has been used in previous research conducted by our group, showing good psychometric properties [Reference Tavano, Sponda, Fabbro, Perlini, Rambaldelli and Ferro18, Reference Perlini, Marini, Garzitto, Isola, Cerruti and Marinelli19]. Shortly, subjects were asked to match a sentence they hear with one out of four vignettes on a PC screen. Only one vignette represents the stimulus target, while the others are grammatical (which have a role of syntactic contrast with respect to the target) or non-grammatical (visual) (which do not have any specific role of syntactic contrast) distractors. The task analyses different grammatical structure such as locative (e.g." The dog is above the chair"), active negative (e.g. "The girl doesn’t run"), passive-negative (e.g. "The piano is not played"), passive-affirmative (e.g. "The car is washed by the child"), and relative (e.g. "The vase that the child is painting is on the chair"). For a more detailed description of the test please refer to Perlini et al. [Reference Perlini, Marini, Garzitto, Isola, Cerruti and Marinelli19].

2.3 Statistical analyses

All the analyses were conducted using R [Reference Team38]. For exploring the presence of differences between the groups on clinical and sociodemographic variables we performed a chi–square test (χ2), for qualitative variables (i.e. gender), and t -tests or Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), for quantitative variables. Then, we employed a hierarchical approach for investigating the differences between the groups in TCGB variables [Reference Goeman and Finos39]. First, a general Multivariate Analyses of variance (MANOVA) with all TCGB variables as dependent variables as well as group, age, TIB and educational level as covariates were carried out in order to explore whether the variable “group” was significant. The MANOVA was carried out between the two groups (whole group of FEP vs HCs) and between the three groups (FEP-NA, FEP-A and HCs). Second, since the assumption of normality, necessary for a standard linear model, was not satisfied, a gamma generalized linear model with identity link function, corrected for Bonferroni, with group, age, TIB and educational level as covariates, was performed separately after we found that the variable group was significant in the MANOVA. Then, for each significant model, a post-hoc analysis was performed and the Holm correction for multiple comparisons was applied. Finally, ANOVAs based on gamma generalized linear model with identity link function with age, TIB and educational level as covariates, were carried out in order to analyse the relationship between clinical features and TCGB scales. We used Bonferroni to correct for multiple testing. Additionally, Cohen's f was employed for measuring the effect size of the regression in order to provide measures of magnitude of the observed correlations. Cohen's f2 values can be interpreted as small (0.02), medium (0.15) and large (0.35) [Reference Cohen40]. Notably, the regressions were considered significant based on both p-value and effect sizes, as suggested by Sullivan and Feinn [Reference Sullivan and Feinn41].

3. Results

3.1 Socio demographic and clinical variables

No statistically significant differences were found in any of the socio-demographic variables between the whole group of FEP patients vs HCs as well as between FEP-NA, FEP-A and HCs, except for the educational level. Specifically, we observed that the whole group of FEP patients had lower educational level compared to HCs (t = 10, df = 227.3, p < 0.001). Similarly, we also found that educational level was different between the FEP-NA, FEP-A and HCs (F(2,321) = 46.5, p < 0.001). Specifically, post-hoc tests showed that FEP-A (z = 5.4, p < 0.001) and FEP-NA (z = 8.3, p < 0.001) had lower educational level compared to HCs. Furthermore, significant differences were observed between FEP-NA and FEP-A patients on some clinical variables. Specifically, we found that FEP-NA patients showed higher PANSS-Total (t = 4.3, df = 112.4, p < 0.001), PANSS-Positive (t = 6.1, df = 113.4, p < 0.001) and PANSS-Psychopathology (t = 3.1, df = 111.4, p = 0.03) compared to FEP-A. Also, FEP-NA patients showed lower GAF scores compared to FEP-A (t= −3.4, df = 79.0, p = 0.01). Finally, the two groups did not differ in terms of PANSS-Negative, HDRS and BRMRS scores as well as in terms of dose of antipsychotics. Socio-demographic and clinical data are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

3.2 Syntactic comprehension

3.2.1 FEP patients vs healthy controls

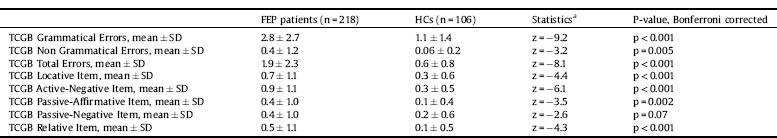

Table 3 and Fig. 1 showed the significant results emerged from the post-hoc analysis.

Overall, the results showed that FEP patients committed more total errors than HCs in the comprehension of syntactic constructions (z = −8.1, p < 0.001). Specifically, they produced significantly greater grammatical (z = −9.2, p < 0.001) and non grammatical (z = −3.2, p = 0.005) errors as well as locative (z = −4.4, p < 0.001), active-negative (z = −6.1, p < 0.001), passive-affirmative (z = −3.5, p = 0.002) and relative (z = −4.3, p < 0.001) errors compared to HCs. No differences were observed in passive-negative sentences (z = −2.6, p = 0.07).

Table 1 Socio-demographic and clinical variables in the whole group of first episode psychosis (FEP) patients and healthy controls (HCs).

BRMRS = Bech-Rafaelsen Manic Rating Scale; df = Degree of Freedom; PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; HDRS = Hamilton Depressive Rating Scale; FEP = First Episode Psychosis; GAF = Global Assessment of Functioning; HCs = Healthy controls; SD = Standard Deviation; TIB = Brief Intelligence Test.

a The statistical tests applied were the chi–square test for qualitative variables and t –tests for quantitative variables.

Table 2 Socio-demographic and clinical variables in the three study groups.

BRMRS = Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Rating Scale; df = Degree of Freedom; PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; HDRS = Hamilton Depressive Rating Scale; GAF = Global Assessment of Functioning; FEP-A = Affective First Episode Psychosis; FEP-NA = Non-Affective First Episode Psychosis; HCs = Healthy Controls; SD = Standard Deviation; TIB = Brief Intelligence Test.

a The statistical tests applied were the chi–square test for qualitative variables and t –tests or Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) for quantitative variables.

Table 3 Differences in syntactic comprehension between first episode psychosis (FEP) patients and healthy controls (HCs).

FEP = First Episode Psychosis; HCs = Healthy Controls; SD = Standard Deviation; TCGB = Test di Comprensione Grammaticale per Bambini.

a The post-hoc tests were calculated on the coefficient of a generalized linear model with gamma and identity link function corrected for multiple testing with Bonferroni correction.

Fig. 1. Significant mean differences in TCGB syntactic comprehension measures between first episode psychosis (FEP) patients and healthy controls (HCs). The post-hoc tests were calculated on the coefficient of a generalized linear model with gamma and identity link function corrected for multiple testing with Bonferroni correction.

Table 4 Differences in syntactic comprehension among the three study groups.

FEP-A = Affective First Episode psychosis; FEP-NA = Non-affective First Episode Psychosis; HCs = Healthy Controls; TCGB = Test di Comprensione Grammaticale per Bambini.

a The post-hoc tests were calculated on the coefficient of a generalized linear model with gamma and identity link function, corrected for multiple comparisons with Holm method and for multiple testing with Bonferroni correction.

3.2.2 Affective FEP patients vs non-affective FEP patients vs healthy controls

Table 4 and Fig. 2 showed the significant results emerged from the post-hoc analysis.

Comparison between the three groups showed that FEP-NA and FEP-A patients committed more grammatical (FEP-NA: z = −9.2, p < 0.001; FEP-A: z = −4.4, p < 0.001), total (FEP-NA: z = −8.2, p < 0.001; FEP-A: z = −3.9, p = 0.002) and active-negative (FEP-NA: z = −5.8, p < 0.001; FEP-A: z = −3.5, p = 0.01) errors compared to HCs. Interestingly, FEP-NA patients also committed more non-grammatical (z = −3.2, p = 0.007), locative (z = −4.7, p < 0.001), passive negative (z = −3.2, p = 0.02) and relative (z = −4.6, p < 0.001) errors compared to HCs. Finally, FEP-NA patients produced more passive-affirmative errors compared to HCs (z = −4.3, p < 0.001) and FEP-A (z = 3.1, p = 0.04).

3.3 Correlations between syntactic comprehension and clinical or sociodemographic variables in FEP patients

No statistical significant correlations were observed between TCGB measures and educational level, PANSS-Positive, PANSS-Psychopathology, HDRS scores, BRMRS scores, GAF scores and dose of antipsychotics in the whole FEP group, except for PANSS-Negative that significantly positively correlated with TCGB grammatical errors (p = 0.04; effect size = 0.06). Additionally, no statistical significant correlations were observed between TCGB measures and educational level, PANNS-Negative, PANSS-Positive, PANSS-Psychopathology, PANSS-Total, HDRS scores, BRMRS scores, GAF scores and dose of antipsychotics in FEP-NA. Similarly, we found no statistical significant correlations between all TCGB measures and these scales also in FEP-A patients, except for TCGB grammatical errors, which were significantly positively correlated with GAF scores (p = 0.049; effect size = 0.04). Finally, with regards to HCs, no statistical significant correlations were observed between TCGB measures and educational level scores.

Please refer to Supplementary Materials for all the tables showing the p-values and effect sizes of the correlations performed between all TCGB measures and clinical or sociodemographic variables in the whole groups of FEP (Table S1), FEP-NA (Table S2), FEP-A (Table S3) and HCs (Table S4).

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in the literature that explored syntactic comprehension language abilities in a large sample of FEP patients.

Overall, we found a greater number of errors in performing the syntactic comprehension test in the group of FEP patients as compared to HCs. This finding is consistent with previous research on patients with SKZ both conducted by our [Reference Tavano, Sponda, Fabbro, Perlini, Rambaldelli and Ferro18, Reference Perlini, Marini, Garzitto, Isola, Cerruti and Marinelli19] and other [Reference Thomas, Leudar, Newby and Johnston12, Reference Kravariti, Reichenberg, Morgan, Dazzan, Morgan and Zanelli15, Reference Xu, Hui, Longenecker, Lee, Chang and Chan16] research groups. Indeed, in Tavano et al. [Reference Tavano, Sponda, Fabbro, Perlini, Rambaldelli and Ferro18] patients with SKZ showed significantly poorer syntactic diversity skills, including narrative and conversational speech, than HCs. Similarly, Perlini et al. [Reference Perlini, Marini, Garzitto, Isola, Cerruti and Marinelli19] reported that patients with SKZ had selective impairments in active-negative sentences, as measured by the same TCGB test employed in our study, compared to HCs. Furthermore, the study also showed that patients with longer history of illness had a more generalized deficit in correctly identifying syntactic constructions compared to HCs [Reference Perlini, Marini, Garzitto, Isola, Cerruti and Marinelli19]. Taken together, these findings suggest that syntactic deficits are a core dimension of psychosis, as also hypothesized by Crow et al. [Reference Crow6, Reference Crow7]. Specifically, according to Crow’s hypothesis, the nuclear symptoms of psychoses represent a failure in establishing the left hemisphere dominance for language, which is one of the most lateralized dimension (most commonly to the left hemisphere) [Reference Crow7]. Indeed, it has to be noted that in the healthy brain syntactic abilities are anatomically sustained by a distributed fronto-temporal network within the left hemisphere, including the inferior frontal gyrus and the posterior superior temporal sulcus [42–Reference Blank, Balewski, Mahowald and Fedorenko46]. Therefore, altered lateralization, which is defined as an inverse asymmetry or a lack of prevalence of one hemisphere on the other, is one of the most replicated behavioral and neuroimaging findings in psychosis, being also present in FEP and in subjects at genetic risk to develop psychosis [47–Reference Crow, Chance, Priddle, Radua and James50]. In this context, we might hypothesize that cerebral asymmetry changes may possibly explain the deterioration of syntactic abilities that we observed in our group of FEP subjects. However, further studies are necessary to confirm these alterations over time.

Fig. 2. Significant mean differences in TCGB syntactic comprehension measures between affective first episode psychosis (FEP) patients, non-affective FEP patients and healthy controls (HCs). The post-hoc tests were calculated on the coefficient of a generalized linear model with gamma and identity link function, corrected for multiple comparisons with Holm method and for multiple testing with Bonferroni correction.

Moreover, our findings showed that both FEP-NA and FEP-A patients committed more grammatical and active negative errors compared to HCs, ultimately suggesting a shared syntactic deficit between the two diagnostic groups. These common syntactic impairments may be understood within the psychosis continuum theoretical framework [Reference Craddock, O’Donovan and Owen51]. The adoption of categorical system alone to classify psychotic disorders has been, indeed, widely questioned in light of evidence showing shared cognitive and brain deficits between non-affective and affective psychosis [52–Reference Lewandowski, Cohen, Keshavan and Öngür54]. Notably, a recent study carried out by our group also reported similar deficits in linguistic and emotional prosodic [Reference Caletti, Delvecchio, Andreella, Finos, Perlini and Tavano55] as well as in comprehension of figurative language [Reference Perlini, Bellani, Finos, Lasalvia, Bonetto and Scocco56] deficits between affective and non-affective FEP patients. Therefore, in line with these evidence, the syntactic deficits observed in both FEP-NA and FEP-A patients may represent a common clinical feature consistent with a possible nosological overlap. However, it is worth noticing that FEP-NA patients showed unique syntactic impairments, with worse performance in non-grammatical, locative, passive-affirmative, passive-negative and relative sentences compared to HCs as well as in passive-affirmative constructions compared to FEP-A patients, ultimately suggesting a more extensive language dysfunction in these patients. This result is also in line with our previous study [Reference Caletti, Delvecchio, Andreella, Finos, Perlini and Tavano55] showing more prominent prosodic deficits in FEP-NA patients compared to FEP-A, as well as with previous research showing more severe neuropsychological deficits in SKZ as compared to BD [Reference Krabbendam, Arts, van Os and Aleman57, Reference Caletti, Paoli, Fiorentini, Cigliobianco, Zugno and Serati58], even when matched for clinical and demographic characteristics [Reference Krabbendam, Arts, van Os and Aleman57]. Furthermore, the more extensive language deficits found in our group of FEP-NA patients could be anatomically sustained by a more remarkable disruption of leftward functional hemispheric lateralization for language observed in SKZ compared to BD, independently of task performance, severity of symptoms, age and gender, as suggested by previous studies [59–Reference Royer, Delcroix, Leroux, Alary, Razafimandimby and Brazo61].

Therefore, based on these evidence, language disturbances seem to have a central role in the presentation of psychotic disorders and it should be considered as a potential target of intervention in FEP patients, as also suggested by a previous study [Reference Roche, Segurado, Renwick, McClenaghan, Sexton and Frawley5].

4.1 Correlations between TCGB measures and clinical variables

Our results showed the presence of significant correlations between clinical symptoms and syntactic abilities only in the whole group of FEP and FEP-A patients. Specifically, we found that PANSS-Negative, for the whole group of FEP patients, and GAF scores, for only FEP-A patients, positively correlated with TCGB grammatical errors, ultimately suggesting that illness severity played a key role in influencing the performance in this test. Interestingly, these results seemed to partially align with the evidence reported by our previous study investigating prosody abilities in a partially overlapping sample, which showed that emotional prosody impairments were significantly correlated with illness severity [Reference Caletti, Delvecchio, Andreella, Finos, Perlini and Tavano55]. Moreover, our results are also in agreement with evidence reporting significant correlations between illness severity and cognitive impairments in BD [Reference Zubieta, Huguelet, Lajiness-O’Neill and Giordani62] and SKZ [Reference Heydebrand, Weiser, Rabinowitz, Hoff, DeLisi and Csernansky63]. Indeed, it has been found that in BD the performance in executive functions was negatively correlated with the number of manic or depressive episodes [Reference Zubieta, Huguelet, Lajiness-O’Neill and Giordani62]. Similarly, Heydebrand et al. [Reference Heydebrand, Weiser, Rabinowitz, Hoff, DeLisi and Csernansky63] also observed that negative symptoms were associated with deficits in memory, verbal fluency and executive functions in first episode SKZ.

Therefore, our study further suggests that clinical symptomatology might play a key role on language deficits in FEP, ultimately proposing the need of a clear clinical stratification of FEP patients for a better understanding of language deficits in these patients. However, it is important to point out that the significant correlations found in our study were characterized by small effect sizes and therefore further studies are warranted to confirm our results.

4.2 Limitations

Although this study investigated language abilities in a large sample of FEP patients, some limitations might have reduced the generalizability of the results and therefore should be taken into account. First, all participating patients were on medication, which may have a potential confounding role. Therefore, future studies on medication-free FEP patients are warranted for ruling out the possible medication effects on language abilities. Second, the specific cognitive abilities were not assessed and they should be considered in future studies, especially because executive functions and working memory have an important role in language abilities, as suggested by previous investigations [64–Reference Wilson, Galantucci, Tartaglia, Rising, Patterson and Henry66]. Nevertheless, in this study we controlled for an estimated measure of the IQ in all the statistical analyses.

5. Conclusion

This study shows that the syntactic comprehension impairments are already present in both FEP-NA and FEP-A patients, confirming that reduced access to syntactic structures is a core impairment of psychoses, in particular in FEP-NA patients. Therefore, given the centrality of language domain for functional outcome, the assessment of different aspects of language and the remediation of linguistic comprehension alterations should be included in routine clinical practice in the early phases of psychosis. Finally, further neuroimaging studies should be warranted in order to explore the relationship between syntactic comprehension impairment and cerebral asymmetry and connectivity at different illness stages.

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Italian Ministry of Health (H61J0800020000 to MR, RF-2016-02364582 to PB) and the Fondazione Cariverona (Promoting research to improve quality of care; Sotto-obiettivo A9 ‘Disability cognitiva e comportamentale nelle demenze e nelle psicosi’ to PB and MR).

Appendix A Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.08.001.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.