On assignment for the New York Times, journalist Frederick Law Olmsted toured the antebellum U.S. South as a cultural outsider. Olmsted was fascinated by the unfamiliar workings of this cotton kingdom, its institution of slavery, and its Black communities. Among the slices of life that he experienced was a funeral in a Black community outside Richmond, Virginia, 1852. Olmsted described the burial of the deceased, noting, at the head of the grave, “an old negro, with a very singularly distorted face” who sang “a hymn, which soon became a confused chant.” The performance entailed “the leader singing a few words alone, and the company then either repeating them after him or making a response to them, in the manner of sailors heaving at the windlass [an anchor-raising device aboard ships].”Footnote 1 Olmsted's previous employment as a seaman would have made him familiar with songs for “heaving at the windlass,” and he could assume likewise for readers having recent experience traveling by ship. Singing such songs, eventually known as chanties—in today's popular rendering, “sea shanties”—had become standard aboard large vessels. Nevertheless, like Olmsted, few readers of the Times would have been familiar with singing in Black communities. Although such “chants” were ubiquitous in African American life, opportunities to encounter them as such were limited for most white individuals, being separated from Black performance spaces by physical distance and racial barriers. Olmsted thus drew the comparison to “sailors heaving at the windlass” not as revelation of a link between a Black community's song and the work singing of sailors, but rather to supply his expected readers with a point of reference to imagine what he heard. Olmsted's was a naïve hearing—a hearing in a context of inexperienced exposure to a sample of what might reasonably be called “authentic” African American singing in contrast to minstrelsy's theatrical representations in the urban North. Without the ability to hear the singers of Olmsted's time, our assessment of relationship between musical expressions discursively positioned as “traditional sailor songs” and “traditional African American music” must be mediated by text and through notions presently attached to those categories. Nevertheless, internal evidence furnished through documents encourages us to note connections. When, for example, Solomon Northup attests to a “Hog Eye” song sung by slaves pattin’ juba during his 1840s bondage in Louisiana, and the same song is attested being sung by Anglo sailors during their work less than two decades later,Footnote 2 what else might we suppose but that plantations were linked to the sea? Still, unable to hear for ourselves, we desire confirmation of aural similarity in the ears of people who did hear. Olmsted's experience provides one such hearing unencumbered, due to its naïveté, by the same biases that later discourse embedded in our minds’ ears.

Similar experience-based comparisons, yet with the opposite ordering—describing sailors’ chanties with reference to African American song—would become abundant and more pointed in subsequent decades of the nineteenth century.Footnote 3 Another New York journalist, William Alden, characterized “sailors’ songs” (by which he meant chanties) as “barbaric in their wild melody.” He added, provocatively, that “The only songs that in any way resemble them in character are ‘Dixie,’ and two or three other so-called negro songs by the same writer… [who] caught the true spirit of the African melodies.”Footnote 4 Alden, however, went beyond mere comparison to assert a claim:

Undoubtedly many sailor songs have a negro origin. They are the reminiscences of melodies sung by negroes stowing cotton in the holds of ships in Southern ports. The “shanty-men,” those bards of the forecastle, have preserved to some extent the meaningless words of negro choruses, and have modified the melodies so as to fit them for salt-water purposes.Footnote 5

Alden's remarks, notwithstanding what many today might find to be a problematic conflation of mediated (popular minstrelsy) and unmediated (dock workers’ singing) presentations of African American musical style, came at the tail of a century of contemporary observations, albeit uneven, of Black Americans’ performances in situ. From the late eighteenth century, casual encounters by white people of Black Americans singing at work most commonly occurred on land and inland waters.Footnote 6 The records of those encounters offer much to support an argument that the song forms and customs that would later be connected with the term chanty indeed originated in Black communities of the Americas.Footnote 7 In addition to empirical data in the form of textual objects that support this origin, inferences about cultural aesthetic orientations may be made from the ways that the Euro-American or European (white) observers in the accounts initially described both the labor and singing of Black people as something unfamiliar or different from their own. These data, beyond the pale of the formative chroniclers of the twentieth century but now at our disposal, suggest that the sailors’ shipboard context for chanties emerged only as the tip of an iceberg of a song style that had spread throughout the African American diaspora during the half-century before Olmsted's tour. From inland spaces, like a Black cemetery outside Richmond, the chanty type was carried back and forth from the territorial peripheries by waterways.

This essay addresses questions about the role of African American culture and Black people in the history of the chanty genre that were largely foreclosed by a post-nineteenth-century white racial framing, in conventional discourse, of chanties qua sailors’ songs.Footnote 8 First among these questions: If this musical form emerged from Black communities on land and did not, as is popularly supposed, derive from earlier forms originating in European ships of greater or lesser antiquity, how did it make its way onto the ocean-going vessels? Second: If it was a cultural practice situated in Black communities, how was it adopted by the predominantly white and presumed culturally divergent community of sailors? The exposition centers on cotton screwing, that work which Alden (above) referred to in his remarks as a site of musicking obscured within the submerged part of the “iceberg” of African American song.

I focus on this adjacent, buried site, cotton screwing, to deliberately approach the questions about sailors’ work singing obliquely. Experience with the robust bias in the dominant discourse has taught me that to approach the preconceived subject of “sea shanties” head on, to bring a radical re-envisioning of these songs, which constitute a genre rooted in African American culture, provokes much dissonance—and resistance. A notable early instance of such dissonance and its unproductive outcome occurred in the 1910s, when the discourse based on lived experience and firsthand observations, from Olmsted to Alden, was giving way to the removed salvage work of nascent folklorists. In his fantastically titled English Folk-Chanteys (1914), famed English song-collector Cecil Sharp's ethno-nationalistic biases were evident, by choice selection of and commentary on chanty repertoire, in his effort to frame chanties as a species of English “folk” song. That same year, a countryman of Sharp's, Frank Bullen, edited a collection with an equally revealing yet differently oriented title: Songs of Sea Labour. Although Sharp, the gentleman folklorist, had only experienced chanties as he heard them sung recently by elderly retired sailors in isolated solo settings in Britain, Bullen, a practicing chantyman of the nineteenth century, learned his first chanties as a teenager from Black stevedores in Guyana in the 1860s.Footnote 9 The introduction to Bullen's work, by a musicologist, W. F. Arnold, proceeded from an assertion that “the majority of the Chanties are Negroid in origin,” and expounded upon stylistic traits of African American music.Footnote 10 Sharp, doubting the role of Black people in shaping what he presupposed to be an ethnically “English” genre, cited neither Bullen and Arnold nor any of the comparisons to Black singing he might have found in earlier-period articles, merely alluding to “the vexed question of [N]egro influence.”Footnote 11 As to resistance: In the 2021 spike of popular interest in “sea shanties,” initiated by a viral moment for the material on the TikTok app,Footnote 12 online commentators’ acknowledgment of the genre's African American connections was met with racism-inflected backlash implying that the acknowledgment was a ploy typical of political liberals to divest white peoples from their heritage.Footnote 13

Cotton screwing was an elaborate process through which cotton bales for export were stowed in the holds of vessels. Although most occupations in the antebellum U.S. South were limited to one or another race of worker, cotton screwing is notable as an occupation, first exclusively of Black men, in which white men also came to engage in equal proportion. Most significantly, it was one of few spaces in North America before the U.S. Civil War—sailing vessels being another—that Black and white laborers occupied together in song.Footnote 14 The cotton screwing workforce, moreover, overlapped with the workforce of sailors, just as the cotton screwers’ songs overlapped their repertoire. Save for some minutiae in application and differences in preference for repertoire, there is no reason to divide the songs of this type according to one or the other profession; all were chanties, musically speaking. Still, despite musical correspondences across contexts stretching even further afield—as heard by Olmsted—it has been the custom to reserve “chanties” for the seamen's songs and, with that, to fallaciously ascribe to “chanty” exclusive associations with sailors and the sea, including an association with whiteness. Cotton screwing, less compromised by such accruals of narrative (for there is little narrative available at all about cotton screwing) is now better positioned to resist the dichotomy of “Black/land” singing and “white/sea” singing.

The greatest significance of cotton screwmen's singing to the questions I have posed, however, lies in a difference between the inter-racial work and music environments of sailing and cotton screwing in terms of which ethnically formulated cultural habits held precedence in the respective spaces of performance. The historical record does not present a picture of white seamen encountering, for the first time, chanty singing by Black shipmates while at their duties at sea. Instead, we find white seamen freshly encountering chanties when interacting with the Black longshoremen in port. Through detailing the particulars of this cross-racial exchange, the summative argument of this essay is that cotton screwing was the foremost context in which white laborers acculturated to the practice of work singing in an African American style.

Remembering Cotton Screwing

Poorly remembered, both in America's public history and in books,Footnote 15 cotton screwing may nevertheless be considered one of the jobs most essential to the nineteenth-century U.S. economy in that its largest export, cotton, could not be delivered profitably without it. The job engaged small gangs of specialized laborers, who were tasked with squeezing as many cotton bales as possible into the holds of outbound ships. “Screwing” refers to the method of using large jacks to force the bales into place. To coordinate and sustain themselves during this highly exerting task, the screwmen (cotton screwers) cultivated a practice of singing. Their singing method and songs’ structure followed a paradigm, comparable to those often found in West African cultural formations, of organizing group labor through a particular format of call-and-response vocalization.

A testament to the power of music to preserve history, most of the little cultural memory of cotton screwing that survives appears within the discourse on sailors’ chanties. Memory was earlier maintained by a thread that ran in the margins of seminal expositions on chanties. Discourse evoking cotton screwing once guided writers to narratives of African American roots of the genre. For example, W. L. Hubbard's History of American Music (1908), calling back to Alden, states, “Most of the songs or chanties…of the American sailor of today are of [N]egro origin, and were undoubtedly heard first in southern ports while the [N]egroes were engaged in stowing the holds of the vessels with bales of cotton.”Footnote 16

The cotton screwing thread disappeared after World War I, by which time British and Anglo-American folklorists and popular writers had taken up their contemporary salvage work and, without the perspective of historiography, sought ancient and/or English folk pedigrees for the chanties of their sailors whose way of life was moribund. Discussants focused on the iceberg's tip, framed by the white racial space of “the Sea.”Footnote 17 They turned to memories of white sailors (especially from the British Isles) in a time when it was rarely possible anymore to hear chanties in practical settings. It is quite likely that the singing style had diverged from that of the time of Olmsted, so that sound, too, cooperated with other perceptions of the Sea as an imagined place to obscure musical correspondence between sailors’ chanties and African American material. Thus, by the time the American folklorist Doerflinger revived the cotton screwing thread in the 1950s, he did not do so to say that chanties reached sailors via cotton screwing. He instead accommodated cotton screwing to the newer narrative of chanties’ origin in a remote European past by reframing the cotton ports as sites of rejuvenation of sailors’ older chanty practice.Footnote 18 On the heels of Doerflinger, the work of Stan Hugill (1961) presented the United States’ cotton wharves as one of many sites of origin for chanty material in its catholic narrative of the genre.Footnote 19

To appreciate the place of cotton screwing in recent cultural memory, where its narrative power has been neutralized, we must understand the enormous weight of Hugill's voice and the influence of his work in and upon today's perceptions of chanties. A British ex-sailor who in his sea career had contact with latter-day chantymen, Hugill cut an authoritative figure in his interactions with the Folk Revival. His Shanties from the Seven Seas and subsequent writings, nonscholarly, yet couched in an academic style, continue to inform the presentations of current chanty performers, and to be cited, in lieu of other handy books, by scholars. The appeal of Hugill's narrative lies in its happy refusal to commit to an argument for a specific origin point of chanties and, instead, to embrace the appealing truism that seafaring culture was international and its music was of mixed derivation. This framing allotted space for African American (and other) contributions in a way that earlier twentieth-century writers, concentrating on Anglo heritage, did not. However, Hugill's exceptionally inclusive approach to what constituted chantymen's repertoire (including numerous items attested or rumored to have been sung in just a single incidence) also gave more space to English products of outlier musical styles and of marginal historical prevalence in primary sources. This unweighted preponderance of English-flavored material enabled the continued presumption that English music was the genre's cultural core, upon which African American music might be treated as just one among many supplemental influences.Footnote 20 One might liken this phenomenon to how Britain could absorb chicken tikka masala, a product of empire, as an unofficial national dish without sacrificing any of its Britishness and while simultaneously reserving the official title for an English dish.Footnote 21 Thus, although more inclusive and recognizing of African American components in the chanties’ tradition, the late-twentieth-century to present “melting pot” narrative found among the genre's well-initiated audiences has not substantially challenged casual audiences’ perception of a normative white racial frame for chanties.

In such a discursive environment, wherein cotton screwers’ singing is remembered as a trivial episode within a sprawling history of international sailors’ heterogenous vocalizations, the activity of cotton screwing is rendered impotent to represent the formative environment out of which developed the generative style and repertoire that became known as chanties. Current-day chanty enthusiasts may encounter cotton screwing through lyrics enshrined in song, especially through the familiar chanty couplet, “Were you ever in Mobile Bay/Screwing cotton by the day.” Although thus forced to learn of that to which “screwing cotton” refers, within the accessible texts devoted to (sailors’) chanties one may find the definition but little further information. The lacuna may be explained by the fact that, despite the exceptional history of cotton screwing as a space inclusive of both white and Black racial identities, it was nevertheless a subcategory of stevedoring which, by long custom (in the Western Atlantic and Caribbean) was essentialized as heavy labor and “Black” work. Sailors’ work, on the other hand, appears to transcend such ethnicized drudgery through its perceived romance, and emerged from the nineteenth century unmarked. That is to say, sailing could be remembered in the default frame of whiteness. Both explicit and tacit racialization when remembering these professions has meant that not only was cotton screwing marginalized in post-nineteenth-century works on “sea” chanties but also that, even while the embers of cotton screwing memories remain, one finds nowhere to turn to for its details.

Without such scholarly or applied interventions as that of Lhamon, which analyzed musicking in early New York's Catherine Market to reveal an inter-racial street culture that defies conventional roles ascribed to Black and white actors in American popular music, or that of the Carolina Chocolate Drops, which carved out greater space for African American traditions in the banjo playing community,Footnote 22 chanties will continue to be perceived as a “white” genre. It should be clear that I do not regard chanties to be a “Black” genre, nor do I assert a unilinear development. However, the predominant lines of development were rooted in the Black expressive forms and customs in the Americas that constitute African American culture. My intervention aims to facilitate new discourse, not only to make chanties’ African American heritage more visible but also to increase its legibility as the foundation of the genre rather than a subordinate influence. The following sections provide the first sustained presentation of screwmen's work singing history, though I lack the space here to make it a comprehensive one. Through recovering and assembling a critical mass of memories, we may at last give cotton screwing full consideration in the discussion of chanties and understand the debt sailors owed to screwmen for their songs.

Cargo Screwing History and Methods

The U.S. cotton trade flourished after the War of 1812, when the textile market in Britain was again available to receive raw cotton.Footnote 23 Export was first centered in South Carolina and eastern Georgia, with Charleston and Savannah being the primary export points.Footnote 24 With the development of territory obtained through the Louisiana (1803) and Florida Purchases (1821), production expanded to the Old Southwest, and Gulf of Mexico ports like Mobile and New Orleans superseded the East Coast ports. In the 1820s, coastwise ships began to bring cotton from the Southern ports to New York first, before shipping to Europe. Other ships brought cotton directly to the major European import sites, Liverpool, Le Havre, and London, whereas manufactured goods from those places were shipped back to the South via New York.Footnote 25 Thence began the Atlantic packet ship trade, in which sailors hailing from the U.S. Northeast and Europe were brought into a network connected to the culture of the U.S. South. Screwing was necessary in order to pack the moderately sized, wooden vessels with enough of the relatively light cargo to make long voyages profitable. In the late nineteenth century, however, huge, steel-hulled steamships alleviated the pressure on storage space.Footnote 26 By the early twentieth century, a method of pressing cotton by machine into “high-density” bales enabled it to be compressed by an additional one third beyond previous methods of either machine or man, meaning the screwmen's profession became redundant.Footnote 27

Details of the work emerge only in pieces and incidentally, in accounts as will be presented here. By way of an initial example, here is a description of the work as the aforementioned chantyman Frank Bullen saw it in Mobile Bay in the late 1860s and 1870s:

After mooring, a gang of stevedores came on board and set to work, with characteristic American energy, to prepare the hold… Below, operations commenced by laying a single tier of bales, side by side across the ship…leaving sufficient space in the middle of the tier to adjust a jack-screw. Then, to a grunting chantey, the screw was extended to its full length, and another bale inserted.Footnote 28

These notes, from a single sailor's travelogue, offer more information on the screwing process than any book about the history of the cotton industry. In addition to such primary sources, invaluable organizational and mechanical details are found in Allen Taylor's M.A. thesis (1968), auxiliary to its focus on labor organizing among screwmen of Galveston during Reconstruction, for which Taylor interviewed at least one retired screwman. Finally, examination of visual evidence helps to complete a picture.

There were many men engaged during the cotton shipping season, the fall and winter months. Three to four gangs of screwmen worked in each hold of a vessel. Although a small vessel might have nine gangs working at once, the later, large vessels with steel hulls (after the 1880s) might have two dozen.Footnote 29 Each gang consisted of five men inclusive of an organizing foreman. Screwmen were ranked above “regular” hand-stowing stevedores in the social-labor hierarchy, being distinguished by their physical strength and special skills.

As such, screwmen were able to command higher wages.Footnote 30 In the time of Taylor's informants, each regular member of a gang was paid five dollars per day and the foreman was paid a dollar more.Footnote 31 Moving backward in time: The subordinate screwmen's and foremen's daily wages in New Orleans were four and five dollars in the mid-1860s, up from three and four dollars in the mid-1850s.Footnote 32 Accounts of the 1840s attest to two dollars as a screwman's daily wage.Footnote 33 By comparison, a seaman in the same packet ships of the 1840s earned twenty-one dollars a month on average, or less than one dollar a day.Footnote 34 These superior wages explain the attraction to the work for the range of social identities to whom the job eventually opened: Enslaved Black, free Black, U.S.-born white, and immigrant white.

Beyond indicating the high market value of cotton screwing, these accounts of wages offer insights related to screwmen's songs. Chanty verses commonly cite one dollar or $1.50 as the wage for cotton screwing, as in the following song:

Although we do not find documentation of this song until the 1860s,Footnote 36 we may conjecture based on the wage cited that such songs (or particular verses) were formulated no later than the 1840s.

Also significant is the fact that foremen were paid more than the rest of the members of a gang. Although one might expect a foreman to rank higher on the wage scale, the fact that his physical labor was far less than the others’ may have provoked friction among the gang were it not for the special value he brought: That of the chantyman whose singing made others’ labor bearable.

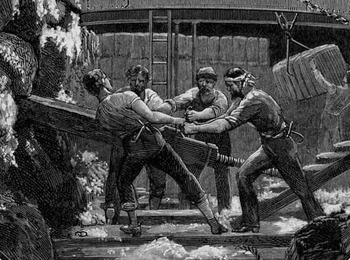

As to the method of working, the few illustrations that exist offer the best insight. One of these (Figure 1) depicts two gangs of what appear to be Black screwmen working in a hold of a vessel at Galveston.Footnote 37 The bales weighed some 500 pounds and measured about 4.5 feet on their longest side.Footnote 38 One can see the bales stowed in layers, with the gang in the background already advanced to a higher layer. As the men approach completion of another row, they lay on the screws to create more space. The foremen of each gang stand above their remaining four members, poised not only to direct the work, but also, as was the custom of call-and-response leaders, at a higher position from which to lead the singing. The screwmen hunch over their jacks, straining, their clothes wet with perspiration. The type of jackscrew seen here weighed over 200 pounds and could be extended to a length of 6 feet.Footnote 39 Its handle consisted of a single iron bar, its ends bent to form just two grips—two grips for four men. The men had to grab onto this handle wherever they could; sometimes they were pulling, sometimes pushing.

Figure 1. Screwing cotton in Galveston, circa early twentieth century. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Screwing cotton into the hold, Galveston, Tex.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed February 12, 2023. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-3d42-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

The screwing process began after the bales had been hand-stowed in a row ending 8 to 10 feet shy of a bulkhead. Protruding from the end of the jackscrew distal to the cotton being worked was the extending screw itself, topped by a forked, wedgelike piece called a “dag,” which allowed the screw-end to lodge firmly in a stout board of hickory, a “sampson post” (seen at left in Figure 1).Footnote 40 The proximal end of the jackscrew was bound around by an iron shoe with protruding metal teeth called a “towband.” This was the end to be pressed against a bale, at right in the photograph. However, because the end of the jackscrew was narrow, the force had to be spread out along the bale by introducing an intermediary block of wood, the “mouthpiece.”Footnote 41 Once secured between post and bale, the handles on the jackscrew were turned to extend its screw.

Figure 2. Planking jackscrew, smaller yet similar in operation to the jackscrew used for screwing cotton. Maine Maritime Museum, Bath, ME. Courtesy: the author.

This all seems simple enough, to put pressure on a row of bales. However, how did one get additional bales into the space now created—and occupied—by the jackscrew and post, which were supporting all that pressure? This was the trick that speaks to the screwmen's skill. Completing the job required another jackscrew; screwmen carried a pair with them. They also carried a pole-like tool called a “dolley.” This was wedged between a post and the bale to maintain the compression at one end of the bale, the inside end. The second jackscrew, called the “tuming screw,” was extended to maintain pressure at the outside corner.Footnote 42 The trick, and a dangerous one at that, was to fit other bales into the space opened up while maintaining pressure, through alternating use of the two jacks and the dolley.

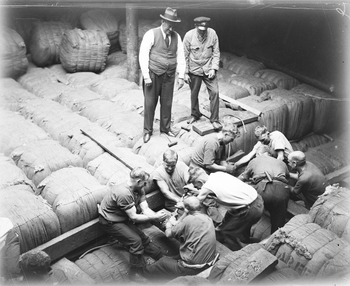

Few outside the profession would have seen the process, which may explain the discrepancies in Figure 3, a drawing published in Harper's in 1883. This illustration appeared within a tableau depicting “Cotton Culture in the South,” each scene showing cotton in one of its stages of manufacture and delivery.Footnote 43 The depiction of New Orleans screwmen at work stands out among the other scenes, not only because it is placed in the center of the tableau, but also because its white actors contrast with the Black figures that appear in all the other scenes. Moreover, the scene catches the eye because its action is so exaggerated. The artist imagined the jackscrew to be enormous. The screwmen's muscles bulge as they look almost to be wrestling a crocodile. Rather than setting down layers of neat bales, they appear to be stuffing a 9-foot high mass of ragged cotton in some general direction. It was, perhaps, the reputation of the profession as a sensationally difficult job that had influenced the artist to sketch such a powerful scene.

Figure 3. Detail of “Cotton Culture in the South,” illustrated by J. O. Davidson, Harper's Weekly, July 14, 1883, 440. Public domain.

At least two other cargoes, sugar and wool, were also screwed. Singing was a part of these activities, too, and their descriptions provide some auxiliary data by which to situate the cultural transfer agency of cotton screwing. Sugar dominated Caribbean commerce as cotton dominated the United States. Although sugar was packed in wooden casks, there was some flexibility to them that made it productive to squeeze them in by means of jackscrew.Footnote 44 There was a firm association between screwing sugar, Black labor, and singing work songs. In Georgetown, Guyana, 1831, a schooner's passenger observed,

After the seamen concluded their day's labour, a gang of negroes came on board, who worked the whole night, discharging cargo or taking on board hogsheads of sugar; and their never-ceasing songs, as they walked round the capstan, or when “screwing” or “swamping” sugars in the hold, left little chance of repose to the whites, who had been at similar work during the whole of the day.Footnote 45

We understand from this that singing was not intermittent or occasional, but rather constant. The practice is ascribed particularly to Black workers (“their…songs”); the white seamen's rest is disturbed by it.

Tropes of cargo screwing moved between sites of different types of work. A sugar-related song, collected from Black roustabouts (the river steamboat equivalent to a stevedore) on the Ohio River, Cincinnati, in 1876, borrowed the stock lyric about the Mobile cotton export.

In the late 1870s, a Nova Scotia sailor heard the following sung in some port during his first voyage from home:

The tropes of “below” (or similar morphemes) and “down” resonate with various kinds of stevedores’ work tasks. That the same tropes are common in sailors’ chanties, and whereas sailors’ tasks did not obviously connect with being or placing something “down below,” we may suppose the stevedoring origins of those songs.

In ports of southern latitudes, wool bales were screwed (Figure 4). Register, however, that sites of this activity were distant ports from those exporting cotton and sugar and comprised of a different demographic. Remembering the port of Durban, South Africa in 1870, Captain Alex Anderson described the process of screwing bales of wool, a cargo destined for London.Footnote 48 Nevertheless, although Anderson mentions sailors’ chanties in his autobiography, singing is conspicuously absent from his account of wool screwing. Likewise, another sailor described wool screwing as he witnessed it in Melbourne in the 1890s without mention of songs, though he, too, notes sailors’ chanties elsewhere in his log.Footnote 49 There is, however, evidence that the chanties were carried to the wool screwmen in Sydney by the end of the century in Australian poet Edwin Brady's poem “Laying on the Screw.” The poem refers to singing chanties “of the stevedorin’ kind” and includes the familiar sounding items “Cheer up, Mrs. Riley” and “Blow, my Bully Boys, Blow.”Footnote 50

Figure 4. Wool screwing in the barque Magdalene Vinnen, Sydney, 1933. Australian National Maritime Museum Collection. 00035587. https://www.flickr.com/photos/anmm_thecommons/7104626313. Public domain.

Thus, screwing was a widespread method of maritime labor. The nature of singing, however, varied according to the cultural formations that were predominant. Sugar screwing, which occurred exclusively within an African American working environment, possessed a regular singing practice. Contrastingly, wool screwing was dominated by white men far from the American bases of chanty singing, and the faint record suggests that chanties were adopted by wool screwmen only after many decades of the songs’ use in the sailing vessels that carried them there. Cotton screwing lay between, straddling Black and white communities of labor. It was situated in centers of African American music that were visited by white sailors.

Early Black Screwmen's Singing

The position of whiteness in the racial frame of shipping may be decentered by remembering that the chief reason for packet ships to visit the Southern ports was to receive products of the labor of Black individuals. The loading of cotton in the U.S. South, as with sugar in the Caribbean sphere, was, at first entirely the work of Black men. The earliest screwmen were enslaved people. Michael Thompson, writing on Charleston's port culture of the antebellum period, explains that slaves had long been employed on the wharves, being permitted by their masters to hire themselves out. In this arrangement, the enslaved workers received a portion of the payment, the rest going to the masters.Footnote 51 As cotton screwing expanded to the Gulf Coast, the labor force included free Blacks and persons of color (“gens de couleur”), who comprised of a large population in the formerly French- and Spanish-controlled cities of New Orleans and Mobile.Footnote 52 The following accounts support a picture of cotton screwing of the 1810s–1830s being a Black labor space. There is no hint, indeed, that white men might have participated—in fact, the labor is actively racialized and even exoticized. Uncannily, the white observers in two of the accounts will be seen to comment similarly, whether or not facetiously, on the “delicious” and “sweet” smell of Black screwmen perspiring, as if not only hard labor and sound but also scent comprised of their racial profile.

From the beginning, Black screwmen accompanied their work with singing. In 1815, the year in which the United States resumed exporting cotton to Europe, Captain James Carr of Bangor, Maine, wrote in his journal about his ship taking in cargo at Charleston. Carr observed the loading of cotton that he would deliver to Liverpool:

[F]or five days I had four pr of Jack screws & four gangs of five each at work on board the ship stowing cotton—I was in the midst of them—it often happened that they all had their throats open at the same time as loud as they cou'd ball [sic]… add to that the savoury smell that may be supposed to arise from twenty negroes using violent exercise in warm weather, in the hot and confined hold of ship and you may imagine what a delicious treat I enjoyed…Footnote 53

Carr did not indicate what those specific screwmen sang, but he did, speaking generally, note the choruses of several “specimens of the african working songs in Charleston.” They included “highland a,” “hoora, hoora, sing talio,” “Ceasar boy Ceasar” [sic], and “huzza my jolly boys, tis grog time a day.” Further down the coast, an observer in Savannah in the autumn of 1818 wrote, “…it is now all activity; nothing is heard near the water but the negroes’ song while stowing away the cotton.”Footnote 54 Another reference from Savannah, in the late 1830s, paints this scene:

[B]elow are the outwardbound ships, stowing away their cotton for the East, and from their gloomy depths comes up the half-smothered, never-ending song of the negro slave. All day long you may hear the same monotonous, melancholy cry.Footnote 55

In the port of City Point on the James River, Virginia, 1830, a white passenger bound for Liverpool observed the screwing of cotton on his ship. Note the way the author otherizes the work:

The head stevadore [sic], a very intelligent slave, took the measure of the space, and selected the bale accordingly… The screw is now set taut, and a handspike attached to the crank, and six powerful negroes take hold and give two or three turns, then hold on a minute. The old boss stevadore [sic], by way of encouragement, says, “Boys, dat bale got to go dar;” one of the darkies commences in a drawling tone, “Massa be berry goodman.” The chorus “whagh,” round goes the screw, crack goes the beams, and in goes the bale… By this time the ebony faces begin to shine like a newly blacked boot, and then comes the sweet smelling savor wafting by, like the spicy breezes of Ceylon.Footnote 56

Black screwmen were connected through their race to the wider network of Black labor, so what they sang, too, may be situated among other African American work singing. Evidence for these wider practices locates them, in this period, along the Western Atlantic rim stretching from the United States’ southeastern region to the Caribbean in the contexts of African American rowing songs and plantation work songs.Footnote 57 The same choruses of “highland a” and “Ceasar boy Ceasar” noted by Capt. Carr have been documented in Anguilla and Nevis, and the forms of the screwmen's songs exemplified here match those sung by interplantation canoe rowers and corn shuckers.Footnote 58 The prominent export sites for cotton were thus nodes in the African American musical network, situated downriver from the sites of these plantation and riverine songs, as well as connected with Caribbean trade.

Seamen as Singing Screwmen on the Gulf Coast

Black screwmen had established the work environment of their profession for some three decades before white workers also began to practice it. The white screwmen's entrance belonged in part to a broader shift in the racial composition of America's manual laborers. In the mid-1840s, white immigrant workers, in some spheres of labor, were replacing their Black counterparts in Southern port cities.Footnote 59 By the 1850s, the number of enslaved Black people in urban New Orleans had declined sharply, as business owners found it more profitable to hire immigrants than to keep slaves.Footnote 60 Irish and German immigrants in particular came to dominate cotton screwing in New Orleans in the 1840s–1850s.Footnote 61 Many of the white screwmen came from the ranks of sailors of the transatlantic cotton trade, including seamen from the British Isles and the northern United States who, keen to avoid the cold winters on the North Atlantic, went ashore to engage in the well-paid work.

White men's participation in cotton screwing appears to have started in or soon after the late 1830s, by which time cotton ports to the west had ascended in importance and most observations of cotton screwing shift to the Gulf of Mexico. Perhaps not coincidentally, writers—white men having acquired closer contact with the work—began to offer richer detail about the singing. The first that I offer here is a transitional account. Englishman P. H. Gosse was in Mobile Bay in 1838 when he observed,

The men keep the most perfect time by means of their songs. These ditties, though nearly meaningless, have much music in them, and as all join in the perpetually recurring chorus, a rough harmony is produced, by no means unpleasing. I think the leader improvises the words… he singing one line alone, and the whole then giving the chorus, which is repeated without change at every line, till the general chorus concludes the stanza.Footnote 62

Importantly, Gosse seems to say that on this occasion the outgoing vessel's sailing crew, not a specialized team of shore laborers, screwed the cotton. Moreover, in contrast to earlier cited accounts, Gosse does not note the race of the workers (cf. “men” to “Negroes”). These facts may suggest that the screwmen on this occasion were white men. Was this the point by which white men began to engage in the cotton-screwing profession, or were they doing the work incidentally as an additional duty—in this case assigned to their vessel's crew?

The form of songs, which Gosse exemplified, matched the familiar sailors’ chanty form, a solo-chorus call-and-response, sometimes appending a grand chorus after each verse. Fixed refrains came in response to improvised solo lines. Lyrics in the following sample evoke the War of 1812, as if topical material from that time had become traditional.

The verbal content of the song appears African American: The “black cock” speaking, the flight to Canada, and the praise of General Jackson.Footnote 64 These elements might suggest that a song originating with Black Americans had been adopted by whites by the late 1830s, though this is unclear.

Accounts of the 1840s do make it clear, however, that cotton screwing was no longer the marked “Black” occupation it had once been. The remembrance of screwmen's singing by Boston sailor F. Stanhope Hill, in Mobile in 1844, does not particularize race, by which we might again infer that the screwmen described were at least partially composed of white men:

It [a load of cotton bales] was now to be forced into the ship, in the process of stowing by the stevedores, with very powerful jackscrews, each operated by a gang of four men, one of them the “shantier,” as he was called, from the French word chanteur, a vocalist. This man's sole duty was to lead in the rude songs, largely improvised, to the music of which his companions screwed the bales into their places… A really good shantier received larger pay than the other men in the gang, although his work was much less laborious.Footnote 65

Within this description, Hill offers one song-text.

The text cribs from the African American rowing song “Grog Time o’ Day,” which had been among the “african working songs” heard on the Charleston waterfront by Carr in 1815.Footnote 67 We must underscore Hill's remark that the sole duty of the “shantier” was to lead the songs.Footnote 68 For it is on this point, and noting the impression it made on the observer, that we may fully register how screwmen's songs and sailors’ chanties alike exhibited a distinctive element of African (-American) work singing: The assignment of such responsibility to the song-leader to consider singing part of the job itself.

Charles P. Low's recollection of his work in an American Black X Line packet ship, 1843, provides the crucial bridge to link the singing practices of screwmen and deepwater sailors. Low's shipmates made a great impression on him with their musical skills:

The crew was made up of the hardest kind of men; they were called “hoosiers,” working in New Orleans or Mobile during the winter at stowing ships with cotton, and in the summer sailing in the packet ships. They were all good chantey men; that is, they could all sing at their work… we could reef and hoist all three topsails at once, with a different song for each one.Footnote 69

In practically forgotten meaning, hoosier was an unflattering term to refer to a white man of the laboring class; sources suggest this usage belonged especially to African American English.Footnote 70 A handful of references, however, like Low's passage and two instances of the “dollar and a half a day” chanty quoted earlier, associate hoosier with screwmen. Perhaps it was the nature of the encounter between Black screwmen and white screwmen, which framed the latter as an exemplar of white labor within Black discursive space, that lent the association. More important in Low's commentary is the implication that singing was a special asset associated with screwmen, and that these fairweather sailors had acquired the skill of work singing through their experiences in the cotton ports. The direction of transfer of skill is clear in this account. Sailors did not bring chanty singing to the longshore workers and nor was this practice, in the mid-1840s, generalized among all seamen. Rather, it was those seamen who had experienced the work of stevedoring on the Gulf Coast who carried the practice to shipboard.

Accounts from this period continue with that of Charles Erskine, a sailor who arrived from Boston in New Orleans in 1846. Erskine was a white sailor who himself, upon arrival, found temporary employment screwing cotton. It turned out to be more than he had bargained for. Screwing required so much strength and stamina that Erskine, working for only 4 days, found it “the most exhausting labor I had ever performed” and “the hardest eight dollars I had ever earned.”Footnote 71

The day after our arrival the crew formed themselves into two gangs and obtained employment at screwing cotton by the day… As the lighter, freighted with cotton, came alongside the ship in which we were at work, we hoisted it on board and dumped it into the ship's hold, then stowed it in tiers so snugly it would have been impossible to have found space enough left over to hold a copy of The Boston Herald. With the aid of a set of jack-screws and a ditty, we would stow away huge bales of cotton, singing all the while. The song enlivened the gang and seemed to make the work much easier. The foreman often sang this ditty, the rest of the gang joining in the chorus.Footnote 72

Thus, we see one way in which seamen became temporary screwmen. Based on the custom of hiring of longshore labor, men desirous of cotton-screwing work had to hook up with a foreman. I reason that the foreman, in order to have the knowledge required for his role, would less likely be an itinerant seaman and rather someone based in the port. As song leaders, foremen may have been the ones to initially teach the songs to the seamen—novice screwmen—entering this cultural sphere. Erskine's language, which portrays singing to enliven work as something novel, implies that he had had little or no experience of singing in this fashion during his prior sailing. Nor does he mention work singing as a sailor anywhere in his memoirs. If it was as new to his shipmates as it was to him, then they were all learning from a foreman outside their crew.

One of the songs Erskine remembered was the “Ringo” song already discussed, wherein “the ringo” is varied as “maringo” whereas the theme remains General Jackson and the Battle of New Orleans. Its tone is of a burial service, evocative of Olmsted's Virginia funeral experience and, perhaps, a metaphor for stowing cotton down below:

Another song, “Highland Laddie,” raises the possibility that white sailors like Erskine had brought their ethnicity's musical tropes to this context. It is a variation of the Jacobite-era Scottish song-form of the same name.Footnote 74 Its lyrics, however, mention both “Mobile Bay” and “Screwing cotton by the day,” indicating the material had been adapted to cotton work.

The richest description of screwmen's work and songs comes from American journalist Charles Nordhoff, who, while serving as a merchant seaman, noted the labor in Mobile Bay in the autumn of 1848:

The men who yearly resort to Mobile Bay to screw cotton, are, as may be imagined, a rough set. They are mostly English and Irish sailors, who, leaving their vessels here, remain until they have saved a hundred or two dollars, then ship for Liverpool, London, or whatever port may be their favorite, there to spree it all away—and return to work out another supply.Footnote 75

Nordhoff reaffirms what we know about the composition of “screw-gangs” and supplies insightful terminology:

Singing, or chanting as it is called, is an invariable accompaniment to working in cotton, and many of the screw-gangs have an endless collection of songs, rough and uncouth…The foreman is the chanty-man, who sings the song, the gang only joining in the chorus, which comes in at the end of every line, and at the end of which again comes the pull at the screw handles… The chants, as may be supposed, have more of rhyme than reason in them.Footnote 76

This narrative contains, so far as is presently known, the earliest published occurrence of the term chanty, albeit embedded in the form of “chanty-man.” For at this point, whereas the style and repertoire of song were in use, this particular label for it was not.Footnote 77 Nordhoff was observing a developing phenomenon.

Among the song-texts Nordhoff gives are versions of the “Ringo” and “Highland Laddie” songs with themes similar to those heard by Gosse and Erskine.Footnote 78 Another song evokes the “mythical personage,” “Stormy,” a pervasive trope of chanties:

“Stormy” presents (again) a “burial” theme reminiscent of spirituals. Indeed, of his impression of the sound of the cotton-screwing songs, Nordhoff wrote, “The tunes are generally plaintive and monotonous, as are most of the capstan [an anchor-raising device comparable to Olmsted's windlass] tunes of sailors.”Footnote 80 As Nordhoff referred to “tunes” rather than lyrics, we may suppose his perception of plaintiveness was influenced by sonic particulars including vocal timbre, melodic contour, pitch inventory, or intonation. I hypothesize that these sonic features might have been shared with African American styles of singing that preceded the invention of the discursive category, “blues.”Footnote 81 Importantly, Nordhoff claimed that his examples would “give the reader an idea of what capstan and cotton songs, or chants, are.”Footnote 82 The wording implies that the work songs of screwmen and sailors of his day were one and the same.

Our final remembrance of cotton screwing and its songs brings us to 1851—the year before Olmsted's tour—when J. D. Whidden shipped from Boston to New Orleans:

The bales were rolled from the levee by the stevedores’ gangs, generally roustabout darkies… where they were received by gangs of cotton-screwers… All this work was accompanied by a song, often improvised… Each gang possessed a good “chantie” singer, with a fine voice…The songs or “chanties” from hundreds of these gangs of cotton-screwers could be heard all along the river front, day after day, making the levees of New Orleans a lively spot. As the business of cotton-screwing was dull during the summer months, the majority of the gangs, all being good sailors, shipped on some vessel that was bound to some port in Europe to pass the heated term and escape the “yellow Jack [fever],” which was prevalent at that season.Footnote 83

Whidden's remarks, based on firsthand experience, connect the dots between the Black ordinary longshoremen, the white screwmen, and transatlantic sailors. They tell us not only that sailors arriving in the South worked temporarily as screwmen to escape the cold season, but also that screwmen of the port worked temporarily as sailors to escape the hot season. A set of white workers, no longer newcomers to the screwing profession, had fully adopted the West African paradigms of embedding song in all their work and of improvising texts. This information renders implausible the idea that such methods—indeed, such a comprehensive and distinctive practice—emerged spontaneously among crews of European ancestry at sea. It points instead to a community of screwmen doubling as sailors who, within the span of a decade, carried their recently acquired “melodies sung by negroes stowing cotton in the holds of ships” across the seas with them.Footnote 84

Conclusion

The near absence of cultural memory of screwing cotton is remarkable in light of its enormous historical importance to the U.S. economy. A large tomb in New Orleans's St. Roch cemetery, its forty-six unmarked vaults containing members of the Colored Screwmen's Benevolent Association (Figure 5), stands as the only public monument in a city where hundreds of screw-gangs worked yearly on the levee for the greater part of a century. When inter-racial amity fractured in 1894 and white screwmen lashed out at the perceived threat of being replaced by Black screwmen, white rioters tossed more than 100 of the Black screw-gangs’ jackscrews into the Mississippi.Footnote 85 Those jackscrews may still lie at the bottom of the river, “down below” with Stormy, and not a single cotton jackscrew could be found in a museum collection. Screwmen's occupational songs, musicking that took place adjacent to the birth of jazz, could neatly be added to the list of New Orleans's contributions to American music—if only local residents knew they existed. These lacunae in cultural memory would be less surprising were it not for enduring memories of the overlapping work singing practices of sailors. Adding insult to injury, the sailors’ chanties, whose heritage memories of cotton screwing would help anchor to places like New Orleans, have been estranged, such that a Scottish TikTok star presently fulfills popular culture's ideal for a chanty-singer's cultural-geographic embodiment.

Figure 5. Detail of society tomb of the Colored Screwmen's Benevolent Association. St. Roch Cemetery, New Orleans, LA. Courtesy: the author.

Since the demise of commercial sailing in the early twentieth century, racialized representations of past sailor culture have affected how sailors’ musicking has been imagined and investigated. It is one thing to recognize the ethnic composition of historical sailors in European and Anglo-American shipping, in which case, the preponderance of white individuals involved (especially in command roles) justifies supposing white actors had overall more social power in that space. Appraising the relationships between race and social power in chanty-singers’ development is, indeed, key to my interpretation. It is another thing, however, to racialize the sailors’ cultural space as essentially “white,” and to align culture with perceived traits of white people as a racial bloc. Once having done so, in a circular process, the learned habits of selection, categorization, narration, and folklorized performance of “sea shanties” qua “white” musicking contribute to maintaining the established white frame.

Paradoxically, hope to recover details of cotton screwmen's musicking occluded by latter-day racial imagining lies in musical and social traits preserved in the sailors’ chanties, of which there is much more documentation. Making those traits legible, however, requires dismantling chanties’ conventional frame of seafaring and understanding cotton screwing work songs and sailing work songs as part of a single, broader musical, kinesthetic, and rhetorical sphere of value—an African American culture-based chanty genre. Having attended to the evidentiary support for this in the foregoing pages, I will now offer answers to questions vexing people who may recognize the musical-cultural traits by which to envision Black actors and African American cultural formations as integral to the foundation of such a genre but who, by the lack of theory, are rendered apathetic in the face of specious counterarguments in prevailing discourse.

In my analysis I presuppose that there is validity in distinguishing dominant and subordinate cultural formations within a social space and that these manifest as such through social subjects’ dynamic actions. Race operates by affecting the culture-shaping actions according to the social power possessed by the race-bearing actors in that space. So, although culture and race must not be conflated, they may be related insofar as culture's “movement,” both geographically and along a scale of influence, is affected by social dynamics, of which race is one. When contemplating the movement of chanty singing (as culture, as practice), I therefore consider racial groups to be relevant. By the same token, the conditions surrounding the movement of racial subjects have a bearing on the transfer of culture. Neither may we assume cultural habits based on subjects’ racial identities, nor should we think it is likely that cultural habits would flourish equally among subjects without regard to race and its connection to power. The truism that sailors were not, in fact, racially homogenous, must not lead us to conclude that the ethnically heterogenous sailor community simply “mixed” subjects’ cultural formations and musics and that chanties were the result. Such a celebratory narrative, as I have intended to dispel, robs us of the ability to treat chanties’ African American components as essential rather than incidental.

An obvious argument for how “Black” performance (African American-style singing) might have come into this predominantly white social space (Anglo-American and European shipping) is that Black sailing crew members brought it. At first glance, this argument accommodates the popular notion that chanty singing already existed as a European paradigm in those ships, in which case what the Black sailors introduced would be contributing to a European cultural base. We now understand, however, that the existence of the chanty genre aboard ships prior to the advent of a Black maritime workforce is not supported by the historical record. This improved understanding leaves us with only one possibility if we persist with the argument that Black sailors brought the genre to ships. This is that Black sailors brought chanty practice wholesale to shipboard life. Notwithstanding my opposition to popular audiences’ incredulity toward this possibility, an incredulity rooted in their reluctance to relinquish the idea that European (white) sailors invented chanty singing without Black people's assistance, I, too, am compelled to reject this scenario. For whereas I wish to acknowledge Black actors, and whereas Black sailors comprise those actors—within the limited “sea” frame of reference—the historical data of racial demographics and, with that, consideration of the dynamics of social power diminish the theory's strength. Black seamen, although not numerically insignificant during the 1830s–1840s, were not present in such numbers and, more importantly, could not wield such power, I believe, as to dictate the structure of work in the potentially diverse yet nevertheless white-dominated shipboard space.

The history of screwmen's singing, presented here, has made visible a superior argument, yet it is one that requires that we shift away from the sea toward a Black-dominated space. The obscuring white racial frame surrounding “sea shanties” has predisposed discussants, even when supplied with the information that chanty singing originated in Black communities, to put white space at the center, whether explicitly or tacitly, and to seek explanations wherein Black actors entered that space. Attention to cotton screwing repositions the frame with Black people at the center, to lead us to the inverse explanation: White people entered Black space. The summary of my interpretation, now enabled by this reframing, is as follows. Because cotton screwing was initially performed by Black Americans who customarily embedded singing in their group work activities, it followed that a singing practice developed with that work. For singing to be a cultural feature of this Black working community, however, did not mean that it was only incidental color. These actors, their cultural performance practice distributed within the social grouping of the “Black” race and thus exerted with social power in a space where that race made up the foundational labor demographic, established the practice as an essential feature of the profession. Although race could be said to be responsible for making chanty singing a part of cotton screwing, having become established as a virtually necessary “tool of the trade,” chanties would cease to depend on race for their existence. The same would be true later, in the case of chanty singing as part of shipboard labor, wherein by the 1850s the practice was so ubiquitous that any man working the deck of a merchant ship, whether hailing from the Hawaiian Islands or the Azores, was brought into its practice as a matter of course. Thus, when white laborers entered the cotton screwing profession in the 1830s, enticed by premium wages, they were compelled to take up the standing custom of singing. Seamen were among those new laborers, and upon entering the labor space they acquired two tools: The jackscrew and the chanty. White seamen who had learned to use these tools gained a reputation as “hoosiers,” distinguishing themselves through cultivation of musical excellence.

In the end, white people did bring chanty singing to ships, but not from Europe. White people had the power to transform white social space, and so the hoosiers did by establishing chanties as a shipboard practice. The hoosiers were, in effect, white men acculturated to performing “Black men's work” and singing “Black men's songs,” though these practices would become unmoored from race as the profession of cotton screwing (and later, sailing) disrupted the ethnic boundaries of labor. Stationed at the mouths of the great rivers, which carried culture from the American heartland, cotton screwmen were positioned between the African American cultural world of the plantation and the European cultural world of international shipping. Still, not all people similarly positioned were inclined to exchange culture, for race was a great buffer. It was the job of cotton screwing that compelled an exchange across racial lines, not just by putting different races in the same space but by forcing the majority social group to engage by necessity with the cultural practices of a minority. Remembering cotton screwing removes chanties from their positioning as quaint songs of trivial interest and reframes them as a critical exemplar of the exchanges that created the Atlantic world.

Acknowledgments

I thank the following individuals who aided my research: Kelly Page and Anne Farrow, Maine Maritime Museum (Bath, ME); Kane Borden and Dean Seder, Mystic Seaport (Mystic, CT); Sean McConnell, Rosenberg Library (Galveston, TX); Graham Duncan, South Caroliniana Library (Columbia, SC); and Todd Harvey, Archive of Folk Culture (Washington, DC). I thank, as well, the anonymous reviewers who helped to refine the argumentation of this essay.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Gibb Schreffler is an associate professor of music at Pomona College in Claremont, California (USA). His research interests focus on work songs of American maritime laborers and hereditary-professional musician communities in India and Pakistan. His works include Boxing the Compass: A Century and a Half of Discourse About Sailors’ Chanties (Loomis House Press, 2018) and Dhol: Drummers, Identities, and Modern Punjab (University of Illinois Press, 2021).