Obesity is a pandemic condition with several social and financial consequences. It has been characterised as a multifactorial health condition resulting from economic, social, behavioural, genetic, and environmental issues(Reference Cohen, Kamarck and Mermelstein1–Reference Cecchini, Sassi and Lauer3). In addition, obesity has been associated with a higher prevalence and earlier incidence of other comorbid diseases, as well as a higher risk of death, especially among women(Reference Di Cesare, Bentham and Stevens4,Reference McHill and Wright5) .

Work-related stress is a consequence of the physical and emotional responses to a high level of job demands and little control over one’s work(Reference Karasek and Theorell6). The prevalence of occupational stress varies by country(Reference Rasmussen-Barr, Grooten and Hallqvist7–Reference Kivimaki, Nyber and Fransson9). A number of studies suggest that individuals who experience this type of stress have physical and emotional problems including alterations in circadian rhythm patterns and increased body weight(Reference Sinha10–Reference Bukhtiyarov, Rubtsov and Yushkova12).

Relatively few studies have investigated the association between work-related stress and obesity in both general and worker populations, and the findings have been inconclusive(Reference Ulhôa, Marqueze and Burgos11,Reference Solovieva, Lallukka and Virtanen13–Reference Da Fonseca, Juvanhol and Rotenberg18) . Additionaly, a systematic review including eight cohort studies showed that only two reported a signficant association between occupational stress and weight gain in women; however, no study identified this relationship in men(Reference Kivimäki, Singh-Manoux and Nyberg14). Stress seems to activate the allostatic system through chronic elevation of cortisol, which alters the responses of the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. These changes cause important hormonal effects that justify the relationship between stress and obesity(Reference Sinha10,Reference Solovieva, Lallukka and Virtanen13,Reference Foss and Dyrstad19,Reference Qian, Morris and Caputo20) .

The shift work system is becoming increasingly common around the world owing to the continuous production process established by the industrial sector(Reference McGlynn, Kirsh and Cotterchio21,22) . Shift work, especially at night, has been associated with increased health impairments, including work-related stress and obesity(Reference Santana-Cárdenas23–Reference Souza, Sarmento and de Almeida26). This aspect has not been sufficiently explored in literature; however, a study failed to identify a interaction between work-related stress and shift work for obesity in a group of female workers(Reference Fujishiro, Lividoti Hibert and Schernhammer27). In the Brazilian context, evidence of this association is scarce. Thus, we aimed to explore the relationship between work-related stress and obesity among female shift workers. Additionally, we also aimed to test the interaction between shift work and work-related stress in this association.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among the female employees of a group of industries, functioning 24 h a day, located in southern Brazil. This group is principally engaged in the manufacture of plastic products for exportation and had approximately 2600 permanent employees in 2017. This was a consecutive sample of adult women aged 18 years or more. All women who had been working in the same shift for more than 3 months were considered eligible for inclusion in the present study (n 583). Women who reported being pregnant (at any gestational stage) and any physical or cognitive limitations that would interfere with the completion of the questionnaire were excluded. Data collection was performed by trained personnel during a face-to-face interview between June and August 2017.

We used the international classification of nutritional status, based on BMI (calculated by dividing body weight in kg by height in m2), for the assessment of the dependent variable. Obesity cases were defined as those with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or more(28). Body weight and height were measured for each participant. Weight measurements (in kg) were made using a digital anthropometric scale (Omron® model HN-289LA) that can accurately measure up to 150 kg, and a resolution of 100 g and height measurements (in cm) were obtained using a Seca Bodimeter 208 (Hamburg, Germany) portable stadiometer with scale increments of 1 mm and a capacity of 95 to 190 cm (Sanny® model Slim Fit). Both body weight and height were measured twice, and the mean value was computed and used to calculate individual BMI.

A standardised, pre-tested questionnaire was used to obtain data on work-related stress and demographic, socio-economic, reproductive, behavioural and occupational characteristics. Work-related stress was assessed using a validated Brazilian Portuguese version of the Job Stress Scale(Reference Alves, Chor and Faerstein29). This scale is a Brazilian version of the Swedish Demand–Control–Support Questionnaire based on the Job Content Questionnaire that was designed to screen for psychological demands, intellectual discernment, decision-making authority and social support in the workplace(Reference Da Fonseca, Juvanhol and Rotenberg18,Reference Karasek, Choi and Ostergren30) . This scale includes seventeen items scored on a four-point Likert scale, with response options ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (often). The JSS total score ranges between 0 and 44. The sum of the values of intellectual discernment and decision-making authority represent control over work. In this study, the social support dimension was not taken into account because it is not required for the determination of job stress. After confirming the normality of the distribution of the dimension scores, they were dichotomised into ‘low’ and ‘high’ based on the mean score identified in the sample. Work-related stress was defined using the quadrants proposed by Karasek(Reference Alves, Chor and Faerstein29,Reference Karasek and Karasek31) : high psychological demands (↑ D) and low control at work (↓ C). The cut-off points for high psychological demands and low control at work were 14·17 (sd 2·34) and 15·35 (sd 2·78), respectively. Cronbach’s α for the overall scale was 0·679, indicating adequate internal consistency.

Data regarding age (18–30, 31–40 and > 40 years), skin colour (white or other), marital status (with partner or without partner), schooling (≤ 8, 9–11 and ≥ 12 years), income (family income categorised into tertiles), leisure physical activity (physically active or inactive), number of daily meals (≤ 3 or ≥ 4), use of sleep medicine (no or yes), hours of sleep (≤ 5 or > 5), menstrual cycle (normal, irregular or no menstruation), parity (nulliparas, one pregnancy or two or more pregnancies) and work shift (day or night) were also obtained for sample description and analysis of potential confounders. The work schedule, provided by the company and confirmed by the participants, was classified as: day shift (between 06.00 and 14.00) or night shift (22.00 onward).

Data were entered into Epidata software with double data entry. Data analysis was performed using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp). Modified Poisson regression with robust variance was used to estimate unadjusted and adjusted prevalence ratios (PR) with 95 % CI(Reference Barros and Hirakata32). We used this approach because the estimated effect size based on OR derived from logistic regression models can be misleadingly high when the prevalence of the dependent variable is high. The following models were sequentially created, based on the conceptual determination model(Reference Victora, Huttly and Fuchs33), to investigate the association between work-related stress and the occurrence of obesity: model I was unadjusted; model II was adjusted for socio-demographic variables; model III was adjusted for model II plus behavioural variables and model IV was adjusted for model III plus reproductive variables. Additionally, the analysis was stratified by work shift (day/night), and the Mantel–Haenszel test statistic was performed to estimate an interaction between shift work and work-related stress exposures on obesity. A value of P < 0·05 was considered significant in all tests.

Results

A total of 583 women were selected for the study. Subsequently, 133 women (22·8 %) were excluded according to the pre-established inclusion criteria, two (0·44 %) were excluded owing to incomplete data as well as 28 women (4·8 %) who were in menopause were also excluded. Finally, the data of 420 women aged 18–59 years (mean 35 (sd 8·3) years) were analysed. Considering 73 % statistical power and a 95 % CI, the final sample had the power to detect a 39 % of difference in the prevalence rate of obesity by occupational stress status.

Most of the participants were machine operators in the company’s production sector (62·4 %). The employees had worked at the company for an average of 73·1 (sd 67·3) months (about 6 years). The participants’ general characteristics are reported in Table 1. The majority of the participants were white (67·8 %), lived with a partner (56·2 %), had studied for 9 to 11 years (78·6 %), did not regularly engage in leisure time physical activity (77·4 %), ate four or more meals a day (59·8 %), obtained more than 5 h of sleep at night (79·4 %) and 29·3 % reported never having been pregnant. In addition, 75·7 % of the sample worked the day shift (Table 1).

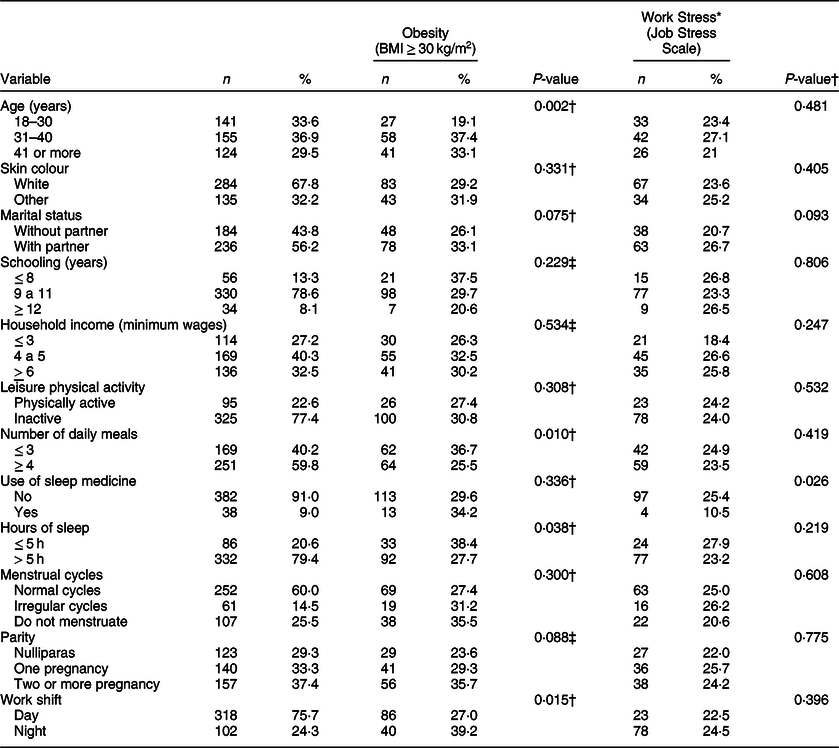

Table 1 Sample characteristics and prevalence of obesity and occupational stress according to demographic, socio-economic, occupational and behavioural characteristics in female shift workers in southern Brazil, 2017 (n 420)

BMI, body mass index.

* ↑ D: High psychological demand; ↓ C: low control over work.

† P-value for Pearson’s χ 2 test for proportional heterogeneity.

‡ P-value for linear trend test.

Table 1 depicts the prevalence of obesity and work-related stress according to demographic, socio-economic, behavioural, reproductive and work shift characteristics. The prevalence of obesity in the entire sample was 30 % (95 % CI: 25·6–34·4), and work-related stress was identified in 24 % (95 % CI: 19·9, 28·1). A higher prevalence of obesity was observed in women who were older (especially among those aged 31 to 40 years), ate three or fewer meals a day, slept five or fewer hours and who had experienced two or more pregnancies. In addition, night shift work was significantly associated with the occurrence of obesity.

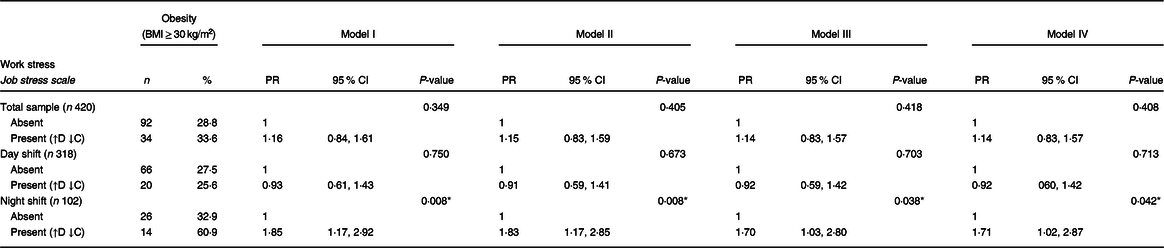

Table 2 describes the associations between work-related stress and obesity. After adjusting for confounding factors, work-related stress showed no significant association with obesity in the overall sample (PR = 1·14; 95 % CI: 0·83, 1·57; P = 0·408). Nevertheless, it was observed an indication of interaction between work-related stress and night shift work on obesity (P = 0·026). After adjusting for confounding factors, work-related stress was associated with a 71 % greater probability of obesity (PR = 1·71; 95 % CI: 1·02, 2·87; P = 0·042) among female night shift workers.

Table 2 Unadjusted and multivariate adjusted values for the association between work-related stress and obesity in the total sample and stratified by work shift (day v. night), of female shift workers in the Southern Brazil, 2017 (n 420)

BMI, body mass index.

↑ D: High psychological demand; ↓ C: low control over work; PR: prevalence ratio; model I: unadjusted analysis; model II: adjusted for age, skin colour, marital status, schooling and household income; model III: adjusted for model II + leisure physical activity, number of daily meals, use of sleep medicine and hours of sleep; model IV: adjusted analysis for model III + menstrual cycles and parity; P-value for Wald heterogeneity test of proportions.

* Statistically significant (P < 0·05).

Discussion

This study investigated the association between work-related stress and shift work and the occurrence of obesity in a sample of Brazilian female workers. We found an indication of interaction between exposure to work-related stress and night shift work on obesity. Additionally, the prevalence of obesity was high among this sample of female shift workers.

The overall prevalence of obesity and work-related stress was 30 % and 24 %, respectively. Previous studies on women reported similar results in the context of obesity: 23·4 % in Asia and 23·9 % in Brazil(Reference Di Cesare, Bentham and Stevens4,Reference Pinto, Griep and Rotenberg34) . On the contrary, the literature presents conflicting results regarding the prevalence of work-related stress(Reference Moore-Greene, Gross and Silver8,Reference Fujishiro, Lawson and Hibert35,Reference Wang, Sanderson and Dwyer36) . Estimates have ranged from 7 % to 38·1 %(Reference Moore-Greene, Gross and Silver8,Reference Fujishiro, Lawson and Hibert35) and have been based on different methods of assessment and identification of high psychological demands and low control over work(Reference Alves, Chor and Faerstein29,Reference Goldberg and Blackwell37,Reference Siegrist, Starke and Chandola38) . We used a Brazilian version of the Swedish Demand–Control–Support Questionnaire based on the Job Content Questionnaire(Reference Alves, Chor and Faerstein29). This was appropriate as the Job Content Questionnaire was originally developed for the industry sector context(Reference Soderfeldt, Soderfeldt and Muntaner39). In this study, the scale’s psychometric properties were satisfactory and similar to another Brazilian studies(Reference Alves, Chor and Faerstein29,Reference Griep, Rotenberg and Vasconcellos40) ; the internal consistency was slightly below the recommended level of 0·70.

In this study, we identified a significant association between work-related stress and the occurrence of obesity among night shift workers. Previous studies investigating this relationship in women have reported inconsistent results(Reference Magnavita, Capitanelli and Garbarino16,Reference Yarborough, Brethauer and Burton17) . Work-related stress seems to be associated with increased body weight(Reference Yarborough, Brethauer and Burton17). It also seems to have an independent association on metabolic syndrome(Reference Santos, Araújo and Griep41). In addition, a prospective study observed a positive and significant linear trend between high work demands or occupational stress and body weight gain(Reference Fujishiro, Lawson and Hibert35). However, in a recent systematic review, such an association was not identified(Reference Magnavita, Capitanelli and Garbarino16).

The association between work-related stress and obesity may be explained by underlying biological mechanisms(Reference Solovieva, Lallukka and Virtanen13,Reference Gralle, Moreno and Juvanhol15,Reference Yarborough, Brethauer and Burton17) . Research in this field has mainly explored chronic social stressors, including harassment at work, conflicts with colleagues and a lack of control and decision-making latitude, that lead to work-related stress,(Reference Yarborough, Brethauer and Burton17) as well as factors such as socio-demographic and genetic characteristics of workers(Reference Solovieva, Lallukka and Virtanen13). The presence of work stress seems to activate the allostatic system that involves the sympathetic nervous system and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis(Reference Foss and Dyrstad19,Reference Qian, Morris and Caputo20) . This response may cause physiological changes in cortisol production, leading to an increase in body weight and the development of obesity. This process can also lead to increased glucose and insulin production, resulting in another homoeostatic series of hormonal disruptions involved in adipose tissue production (resistance to leptin: satiety hormone; increased action of ghrelin: appetite hormone and increased release of neuropeptide Y: production of adipose tissue)(Reference Sinha10,Reference Solovieva, Lallukka and Virtanen13,Reference Foss and Dyrstad19,Reference Qian, Morris and Caputo20) .

Night shift work was significantly associated with the occurrence of obesity as well as the interaction between work-related stress and obesity. These results are consistent with previous findings, where exposure to shift work, including night work, was demonstrated to be an important factor in the risk of certain health complications, including the development of obesity(Reference Olinto, Garcez and Henn24,Reference Sharma, Laurenti and Dalla Man25,Reference Canuto, Garcez and Olinto42–Reference Sun, Feng and Wang44) . Working at night goes against the body’s natural pattern, causing physiological changes related to circadian rhythm (sleep–wake cycle deregulation). Therefore, working at night may affect the metabolism, leading to weight gain, changes in dietary behaviour and physical activity and development of stress(Reference Nea, Kearney and Livingstone43,Reference Medic, Wille and Hemels45) . In addition, the physiological changes resulting from work stress seem to be similar to those resulting from night work exposure(Reference Nea, Kearney and Livingstone43,Reference Jin, Hur and Hong46) . There is scarce evidence in the literature about the relationship between work-related stress and obesity in female shift workers. However, a recent prospective study conducted with nurses in the USA revealed that in the presence of job strain, night work led to an increase in body weight and BMI(Reference Fujishiro, Lividoti Hibert and Schernhammer27). In addition, night shift duration had an inverted U-shaped association with weight gain(Reference Fujishiro, Lividoti Hibert and Schernhammer27).

The association of shift work with overweight or obesity was previously explored in the Brazilian context(Reference Silva-costa, Rotenberg and Coeli47–Reference Macagnan, Pattussi and Canuto50). These studies showed conflicting results and most of them were conducted in healthcare workers(Reference Griep, Bastos and da Fonseca48,Reference Siqueria, Griep and Rotenberg49) . Night work exposure seems to promote a greater increase in BMI in men than in women(Reference Silva-costa, Rotenberg and Coeli47); however, another studies suggested that night shift is related to BMI or overweight increases in both sexes(Reference Griep, Bastos and da Fonseca48,Reference Macagnan, Pattussi and Canuto50) . Additionally, changing from day to night work seems to influence weight gain and BMI increase(Reference Siqueria, Griep and Rotenberg49).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore this relationship in a sample of Brazilian female shift workers. The strengths of this study include the use of a representative sample of women working in shifts for at least 3 months (the minimum exposure period required to produce adverse health effects)(Reference Fujishiro, Lividoti Hibert and Schernhammer27) Also, we used instruments that have been validated for use in the assessment of work-related stress in Brazilian population groups(Reference Alves, Chor and Faerstein29). However, the results of this investigation must be interpreted within the context of an important limitation. Owing to the cross-sectional design, we acknowledge that reverse causation cannot be completely ruled out; therefore, the association between work-related stress and obesity should be interpreted with caution. Another limitation is that male shift workers were not included in this study. For this reason, no comparison by sex could be performed. Despite these limitations, the present study explored important confounding factors in the multivariate analysis, and work shift was explored as a potential effect modifier.

The findings indicated coherence and consistency in the associations explored, including a high prevalence of obesity and work-related stress, especially among women aged 31 to 40 years, who experienced hormonal changes, did not get adequate sleep and worked in the night shift (factors that alter metabolic rate). Therefore, these results support the possibility of a biological mechanism underlying the association between work stress and obesity. However, bidirectionality in this relationship cannot be ruled out. Finally, this study included only women who worked in fixed shifts, which contributes to reinforcing the consistency of the association between work-related stress and obesity in female night shift workers.

Conclusion

In this study, we revealed that exposure to work-related stress and night shift work were associated with obesity among female shift workers. Furthermore, the prevalence of obesity was high among shift workers. These results demonstrate that efforts to reduce work-related stress should be a prevention strategy to reduce the risk of obesity in night shift workers.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: MTO received research productivity grants from the Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technological Development – CNPq (process numbers 307257/2013-4 and 307175/2017-0). A.G. received a post-doctoral fellowship from CNPq (process n. 152923/2018-7), and J.C.S. received a master fellowship from the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduated Education – CAPES (Financing Code 001). Financial support: This work received financial support from the Social Service of Industry of Rio Grande do Sul – SESI-RS, Brazil. The funding service had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation or approval of the manuscript. Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Authorship: J.C.daS., H.T. and M.T.A.O. participated in all stages of the research, from project design, data collection, analysis, construction and review of the article. A.G. participated in data analysis, construction and review of the article. G.H.C. participated in the review of the article. Ethics of human subject participation: ‘This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Vale do Rio dos Sinos, RS, Brazil (project number 2·057·810/2017). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.’